Abstract

The myb proto-oncogenes are thought to have a role in the cell division cycle. We have examined this possibility by genetic analysis in Drosophila melanogaster, which possesses a single myb gene. We have described previously two temperature-sensitive, recessive lethal mutants in Drosophila myb (Dm myb). The phenotypes of these mutants revealed a requirement for myb in diverse cellular lineages throughout the course of Drosophila development. We now report a cellular explanation for these findings by showing that Dm myb is required for both mitosis and prevention of endoreduplication in wing cells. Myb apparently acts at or near the time of the G2/M transition. The two mutant alleles of Dm myb produce the same cellular phenotype, although the responsible mutations are located in different functional domains of the gene product. The mutant phenotype can be partially suppressed by ectopic expression of either cdc2 or string, two genes that are known to promote the transition from G2 to M. We conclude that Dm myb is required for completion of cell division and may serve two independent functions: promotion of mitosis, on the one hand, and prevention of endoreduplication when cells are arrested in G2, on the other.

Keywords: Cell cycle, transcription factor, proto-oncogene, G2/M, endoreduplication, diploidy

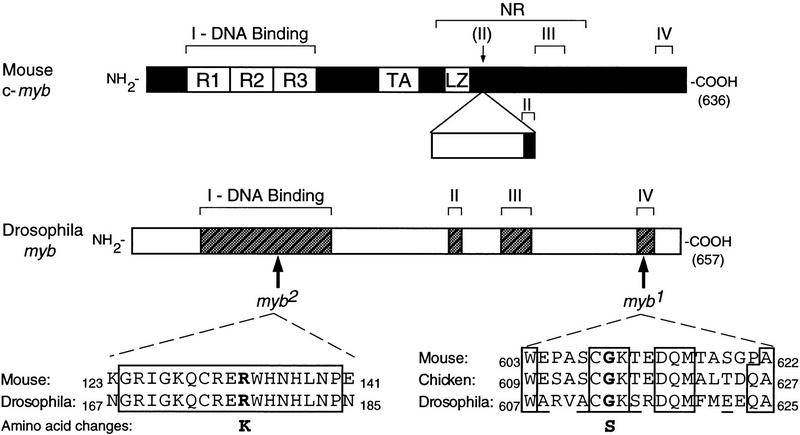

The proto-oncogene c-myb was first encountered as a transduced retroviral oncogene v-myb, which causes a myeloid leukemia in chickens and transforms myeloid cells in culture (for review, see Lyon et al. 1994; Thompson and Ramsay 1995). Mutations affecting c-myb have since been implicated in tumors of mice and humans (Lyon et al. 1994; Thompson and Ramsay 1995). The product of c-myb (Myb) is a transcription factor that binds a specific sequence in DNA (Biedenkapp et al. 1988; Weston and Bishop 1989). The protein is divided into at least three discrete functional domains (Fig. 1): one for binding to DNA, a second for activation of transcription from other genes, and a third that governs the biochemical activity of the protein (Gonda et al. 1996; Kanei-Ishii et al. 1996). Vertebrates possess two additional genes that are related to c-myb, known as A-myb and B-myb (Nomura et al. 1988). The proteins encoded by these genes (MybA and MybB) also function as transcription factors (for review, see Kanei-Ishii et al. 1996).

Figure 1.

Mutant DMyb proteins contain amino acid substitutions at evolutionarily conserved positions. (Top) A schematic representation of the mouse c-Myb protein. The four regions of conservation shared between vertebrate and Drosophila Myb proteins are indicated by Roman numerals. (R1, R2, and R3) Three imperfect tandem repeats that comprise the DNA-binding domain (region I); (TA) transcriptional activator domain; (LZ) leucine zipper; (NR) negative regulatory domain. Also depicted is an additional region encoded by an alternatively spliced exon that contains the majority of conserved region II (Lyon et al. 1994). (Middle) A schematic representation of the DMyb protein. Positions affected by the myb1 and myb2 mutations are indicated. Mouse and Drosophila amino acid sequences for the region in the DNA-binding domain that contains the myb2 mutation are shown by labeled arrows (Gonda et al. 1985; Katzen et al. 1985; Peters et al. 1987). In this region, chicken and human sequences are identical to the mouse sequence (Gerondakis and Bishop 1986; Majello et al. 1986). Mouse, chicken, and Drosophila amino acid sequences for region IV, which includes the myb1 mutation, are shown at bottom. Identical amino acids are boxed, and conservative amino acid differences are underlined. Affected amino acids and the substitutions are shown in bold. Mutations are myb1: GGC → AGC, Gly → Ser, amino acid 613; myb2: AGA → AAA, Arg → Lys, amino acid 177. We also found three nucleotides that differed from the published sequence (Peters et al. 1987) in all three of our strains, only one of which affected the amino acid sequence. At base 281, located in the 5′-untranslated region, cytosine was replaced by guanine. At base 1016, which corresponds to the third base of codon 137 located in the DNA-binding domain, thymine is replaced by cytosine; the amino acid (glycine) is unchanged. At base 1714, which corresponds to the second base of codon 370 located in an unconserved region of the protein (amino-terminal to region II), thymine is replaced by cytosine; this results in a codon for alanine (GCC) instead of the published valine (GTC).

It is generally believed that Myb plays a role in the cell division cycle, specifically at the G1/S transition (Lyon et al. 1994; Thompson and Ramsay 1995). The most direct evidence has come from experiments with antisense oligonucleotides directed against c-myb, which block entry of cells into the S phase of the cell cycle (Calabretta 1991). The validity of these results has been challenged, however, because the antisense oligonucleotides are said to inhibit cellular proliferation in a nonspecific manner (Burgess et al. 1995). MybB has also been implicated in the G1/S transition (Lyon et al. 1994; DeGregori et al. 1995; Kanei-Ishii et al. 1996; Robinson et al. 1996), whereas MybA is more likely to be involved in cellular differentiation (Trauth et al. 1994; Kanei-Ishii et al. 1996). Genes that encode transcription factors with DNA-binding domains related to that of Myb have also been identified in yeast and plants (Paz-Ares et al. 1987; Tice-Baldwin et al. 1989; Ohi et al. 1994). One of these (the cdc5 gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe) has been implicated in the G2 phase of the cell cycle (Ohi et al. 1994).

In an effort to define further the cellular function of myb genes, we have turned to genetic analysis of the single myb gene found in Drosophila melanogaster, Dm myb (Katzen et al. 1985). The protein encoded by Dm myb (DMyb) is approximately the same size as vertebrate Myb (Peters et al. 1987), and the two proteins share four regions of homology, including the DNA-binding domain (Fig. 1). Similar regions are also present in MybA and MybB. Because Dm myb is equally similar to each of the vertebrate myb genes and is currently the only myb-related gene identified in Drosophila, it may represent the progenitor of all three genes and encompass their combined functions.

Previously, we have described two temperature-sensitive mutants of Dm myb whose effects revealed a requirement for myb in diverse cellular lineages throughout the course of development (Katzen and Bishop 1996). It appeared that myb might be essential only during periods when cells are mitotically active. We now report a cellular explanation for these findings by demonstrating that Dm myb may have two distinctive functions during the cell-division cycle: promotion of mitosis, on the one hand, and prevention of endoreduplication of DNA when cells are arrested in G2, on the other. The two mutant alleles of Dm myb produce the same cellular phenotype, although the responsible mutations are located in different functional domains of DMyb. These results implicate myb in the mitotic portion of the cell division cycle for the first time and represent the first direct implication of a transcription factor in the G2/M transition.

Results

The nucleotide sequences of Drosophila myb1 and myb2

Before extending our analysis of the phenotypes caused by the mutant alleles of Dm myb, we characterized the nature of the genetic damage affecting the two alleles. Analysis with restriction enzymes revealed no evidence of chromosomal rearrangements or deletions. We therefore cloned the two mutant alleles and their wild-type counterpart and then determined the nucleotide sequence of the myb-coding domains within the clones. The results are summarized in Figure 1. Each mutant allele contained a single nucleotide substitution resulting in the change of an amino acid perfectly conserved between DMyb and its vertebrate counterparts (Fig. 1). The amino acid substitution in myb1 (Gly → Ser) is considered to be neutral, whereas the substitution in myb2 (Arg → Lys) is highly conservative (McLachlan 1971). These relatively mild changes are consistent with the temperature-sensitive and hypomorphic natures of the mutant phenotypes (see Discussion).

The myb2 mutation occurred within the second of three imperfect tandem repeats that comprise the DNA-binding domain of DMyb (Peters et al. 1987; Kanei-Ishii et al. 1996). In contrast, the myb1 mutation occurred near the carboxyl terminus of DMyb, within the fourth region of conservation shared between the Drosophila and vertebrate proteins (Bishop et al. 1991). No specific activity has been ascribed to this region, but its strong evolutionary conservation (47% identity between DMyb and chicken Myb) along with the phenotypic defects associated with the myb1 mutation, indicate that this domain has functional importance.

Wing defects observed in myb mutants raised at temperatures permissive for viability

Previously, we reported that myb1 and myb2 are temperature sensitive for lethality [myb1 viable at 18°C, but not at 25°C; myb2 viable at 18°C and 25°C, but not at 28°C (Katzen and Bishop 1996)]. In addition, the lethal phenotype is tighter when either mutation is carried over a deficiency chromosome that deletes the myb gene [Df(1)sd72b26] than when either of the mutations is homozygous, indicating that both alleles are hypomorphic rather than null.

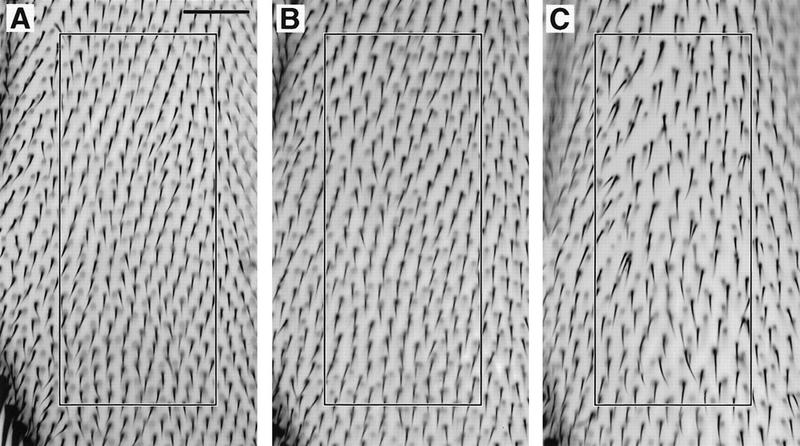

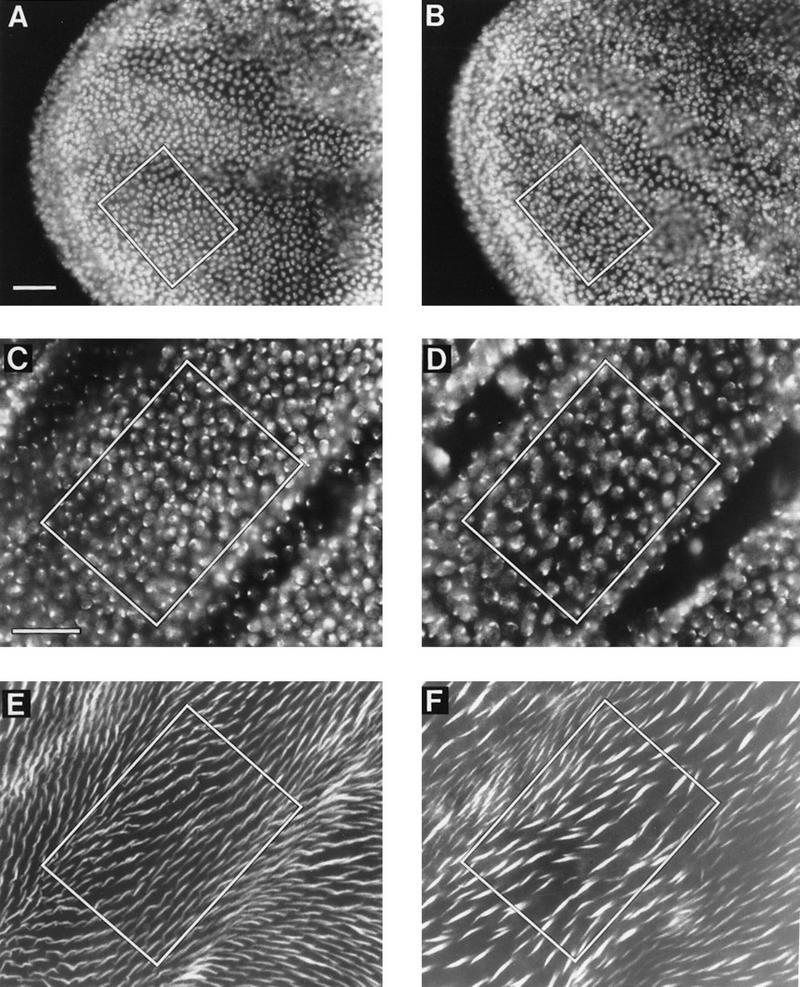

myb1 and myb2 mutants raised at temperatures permissive for viability (18°C and 25°C, respectively) were not grossly malformed, but closer inspection of adults revealed several defects, the most obvious of which occurred in the wings (Katzen and Bishop 1996). These findings indicate that although temperatures of 18°C and 25°C are permissive for viability of myb1 and myb2 mutants, respectively, they are not completely permissive for myb function. We will therefore refer to these temperatures as semi-permissive. When wings from the myb1 mutant and the parental white (w) strain raised at 18°C were mounted and examined under low magnification, mutant wings were approximately the same size and shape as parental wings, but appeared to be considerably cruder (Fig. 2A,B). In particular, wing veins were thicker and differed slightly in their relative positions. Inspection of wings at higher magnification revealed that the mutant wings had approximately half the number of hairs as wild-type wings, and that mutant hairs were considerably larger than normal (Fig. 2D,E; Table 1). Hairs were less regularly spaced, less uniform in orientation, and occasionally grouped in small clusters, indicating a disturbance of tissue polarity (for a review on tissue polarity, see Adler 1992). Bristles on mutant wings were not obviously reduced in number, but did appear to be larger and less uniform in orientation. One copy of the wild-type Dm myb transgene completely rescued the wing phenotype (Fig. 2C,F; Table 1), demonstrating that the wing defects were attributable to the lesion in the Dm myb gene.

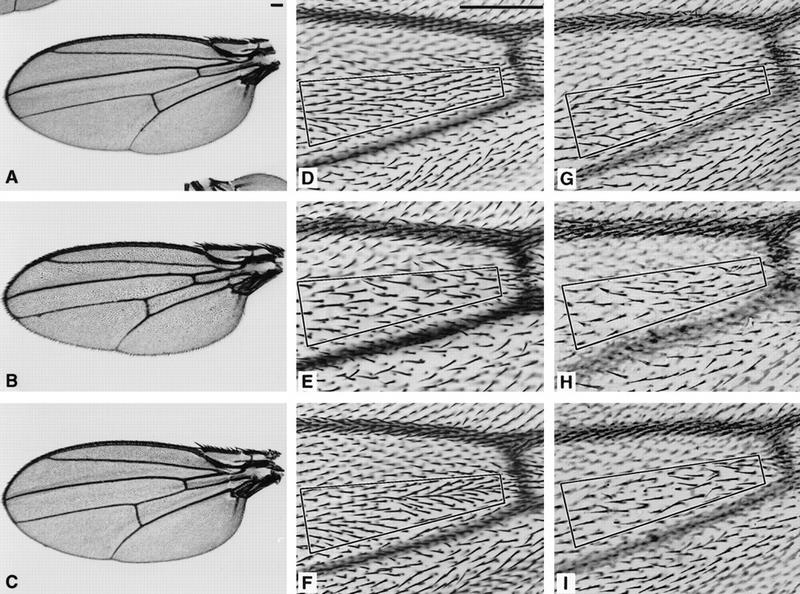

Figure 2.

Mutant myb wings were cruder than wild-type wings and had fewer, larger hairs that were not uniformly oriented. Wings were dissected from female flies raised at 18°C unless otherwise specified. Bars in A and D, 0.1 mm. Complete wings for white (A), myb1 (B), and myb1; P(w+,myb+)/+ (C) are shown at the same magnification. D–I are shown at the same magnification, and the number of hairs located within the boxed area of each panel is indicated below in brackets. When compared with the parental w strain (84 hairs) (D), the number of hairs in myb1 mutants (39 hairs) (E) was decreased by approximately half. This phenotype could be fully rescued by a wild-type Dm myb transgene, shown in F [myb1; P(w+,myb+)/+ (86 hairs)]. The reduction in hair number was significantly less in myb2 flies raised at 18°C (68 hairs) (G) but was stronger when myb2 was carried over a deficiency chromosome at 18°C myb2/Df(1)sd (43 hairs) (H), or when myb2 flies were raised at 25°C (46 hairs) (I).

Table 1.

The relative cell number on wings of different genotypes under varying conditions, as measured by hair counts

| Genotype

|

Temperature (°C)

|

18°C–28°C temperature shiftb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18

|

25

|

25–heat shocka

|

||

| white (w) | 1.00 ± 0.02 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 1.00 ± 0.06 | 1.00 ± 0.04 |

| myb1 | 0.52 ± 0.05 | |||

| myb1; P(w+,myb+)/+ | 1.00 ± 0.07 | 1.00 ± 0.09 | ||

| myb2 | 0.82 ± 0.05 | 0.60 ± 0.09 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.55 ± 0.04 |

| myb2/Df(1)sd72b26 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | |||

| myb2; HS–Dm cdc2/+ | 0.79 ± 0.08 | |||

| myb2; HS–Dm cdc2AF/+ | 0.81 ± 0.03 | |||

| myb2; HS–stg/+ | 0.78 ± 0.12 | |||

In each experiment, the number of hairs in white wings is assigned the value of 1.0. The relative numbers represent the averages with standard deviations of a minimum of five sampled areas. For each experiment, at least two regions of the wing were examined.

(HS) Heat shock.

For conditions, see legend to Fig. 5.

For conditions, see legend to Fig. 7.

Wings dissected from myb2 mutants raised at 18°C were much less severely affected, with respect to both quantity and orientation of hairs, than were myb1 wings (Fig. 2G; Table 1). However, when wings were dissected from myb2/Df(1)sd72b26 females, which occasionally survive at 18°C, or from myb2 mutants raised at 25°C, the defects were more extreme, closely resembling the myb1 phenotype (Fig. 2H,I; Table 1). These results reinforce the evidence from viability studies that myb2 is a hypomorphic allele (retains subpar activity), as two copies are better than one (myb2 homozygote vs. myb2/Df(1)sd72b26) and the severity of wing phenotype is temperature sensitive (18°C vs. 25°C).

The wing phenotype results from a defect in cell division

In wild-type wings, each cell that is not specialized for another purpose is represented by a single hair (Postlethwait 1978). Therefore, the reduced density of hairs on mutant wings indicated that either these wings had fewer cells, each of which was larger, or they had the same number of cells as wild type, but only some of the cells made hairs. Because we were unable to stain adult wings for any cellular structure, the correspondence between cells and hairs could not be determined at this stage. We also failed to obtain any useful information from third instar larval wing disks, both because of their complex folding patterns and because of the difficulty of obtaining enough disks at exactly the same stage of development. In contrast, pupal wings proved to be both accessible and informative. We concentrated on the wings of myb1 mutants raised at 25°C, assuming that the mutant phenotype would be most extreme under these conditions.

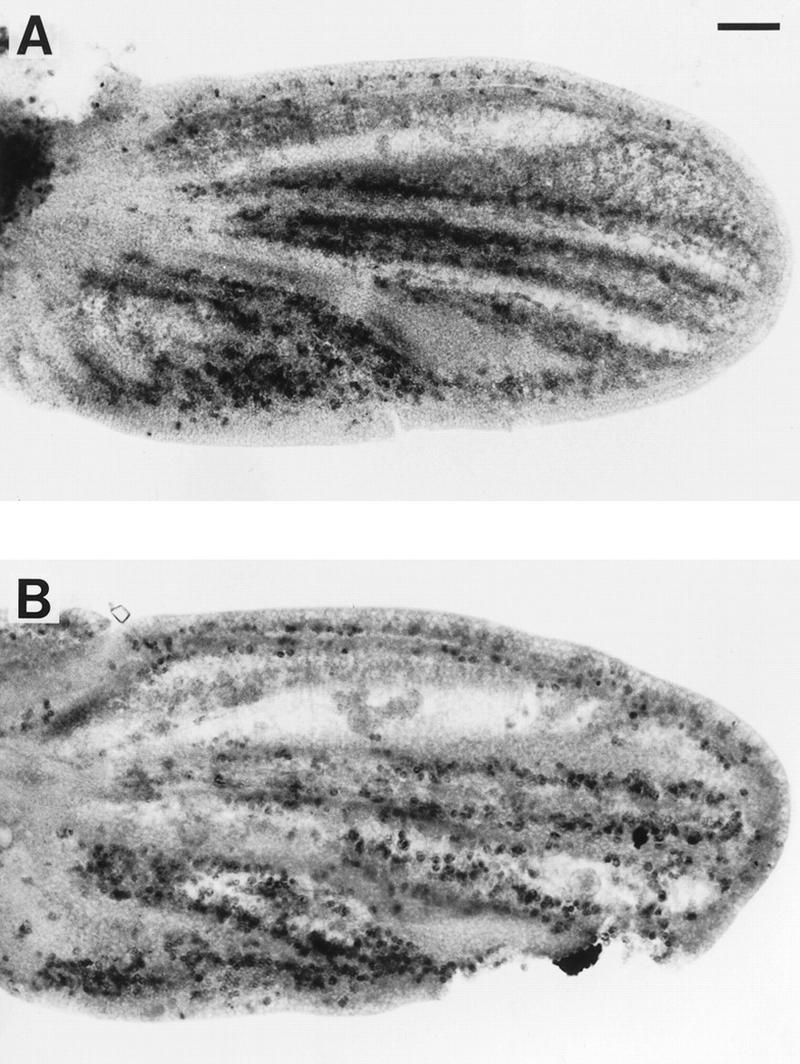

Developing wings from myb1 mutants and the parental w strain were dissected out of prepupae at 6 hr after puparium formation (APF) and treated with the DNA stain, DAPI. No difference was detected between the mutant and wild-type wings (Fig. 3A,B). In contrast, for wings dissected out of pupae between 24 and 36 hr APF, the density of nuclei in any given region of the mutant wing was approximately half of that found for the same region of a wild-type wing, and the mutant nuclei were larger than their wild-type counterparts (Figure 3C,D). No apoptotic nuclei were observed in any of the DAPI-stained samples. The more mature wings (36 hr APF) were also stained with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin (an F-actin-specific stain) to visualize the developing hairs (prehairs) (Wong and Adler 1993). For both mutant and wild-type wings, a one-to-one correspondence was found between the number of nuclei and the number of prehairs (Fig. 3C–F). Taken together, these data show that the mutant wings had fewer cells, each of which was larger and produced a hair.

Figure 3.

myb1 mutant wings had half the number of nuclei as wild-type wings, a defect that occurs during the last cell division. Shown are regions of developing wings dissected from animals raised at 25°C. Wings were treated with either DAPI alone or DAPI and rhodamine-labeled phalloidin (a stain that highlights wing prehairs because they contain high levels of F-actin). The number of nuclei or hairs located within the box in each panel is indicated below in parentheses. Bars, 0.025 mm. DAPI staining of prepupal wings at 6 hr APF showed that at this stage, the nuclear density in A [w (parental strain) (152 nuclei)] and B [myb1 (155 nuclei)] was the same. DAPI staining of pupal wings at 36–37 hr APF showed that at this stage, the nuclear density in C [w (153 nuclei)] was approximately twice the density in myb1 (83 nuclei) (D). Note that the myb1 nuclei were larger than the w nuclei. Phalloidin staining of the same wings as shown in C and D, E (155 hairs) and F (82 hairs), respectively, showed a one-to-one correspondence between numbers of nuclei and hairs for both wild-type and mutant animals.

The preceding results point to a defect in cellular proliferation during the final stages of wing development in the Dm myb mutants. We can infer the nature of that defect by reference to previous descriptions of how the wings of Drosophila mature (Schubiger and Palka 1987). At 3 hr APF, all wing cells except those at the anterior and posterior margins arrest synchronously in G2. The arrest persists until 12 hr APF, when mitosis occurs, followed by an additional cell division cycle that is completed by 24 hr APF. Thereafter, the cells remain in G0. When examined during the early G2 arrest (at 6 hr APF), the number of wing cells in myb1 mutants was normal, but in postmitotic wings (after 24 hr APF), the number of wing cells in myb1 mutants was half that of wild type. For technical reasons (see below) it was not possible to examine the wings between 7 and 24 hr APF, the period during which the final cell cycles occur. If both of the cell cycles that normally ensue were defective, the number of cells should be reduced by a factor of four. Thus, we conclude that it is likely that the final cell division fails to occur in the mutant wings.

Mutant wing cells are blocked before the G2/M transition

The preceding experiments did not define the stage during the last cell cycle at which the mutant Dm myb wing cells were halted. We decided to ask whether these cells entered S phase during the last cell cycle by testing for their ability to incorporate BrdU. Unfortunately, because the wing cells have secreted pupal cuticle that is very securely attached to the cell surface, pupal wings at the developmental stage of interest (12–18 hr APF) are very difficult to handle, but at 24 APF, the cuticle detaches from the wing surface and can be dissected away from the wing. Consequently, we used an approach described by others for injecting BrdU into developing pupae, and allowing them to mature to a convenient stage before dissecting out the wings for further processing and analysis (Schubiger and Palka 1987; Hartenstein and Posakony 1989). Using this method, Schubiger and Palka (1987) showed that the BrdU pattern observed in imaginal disks corresponds to a short pulse (1–2 hr) of BrdU labeling after injection. Their studies also showed that only one S phase (spanning ∼12 to 20 hr APF) occurs in the wing cells of interest during pupal development. Therefore, any labeling observed should correspond to the final S phase.

We selected pupae that were either 12–13 hr APF formation or 15–16 hr APF for injection with BrdU and allowed them to develop until 36 hr APF. For both time periods, BrdU incorporation was detected in the mutant as well as in the parental wings (Fig. 4A,B), indicating that both wild-type and mutant disk cells were actively replicating DNA. The patterns of BrdU incorporation for the myb1 wings indicated that they were less mature than the wild-type wing, a finding that is consistent with our observations that myb1 mutants developed more slowly than the parental flies. We conclude that myb1 mutant wing cells entered into their final S phase but did not undergo a final division, presumably leaving them with a 4C content of DNA (see below).

Figure 4.

myb1 mutant wing cells entered S phase during the final cell cycle. Shown are developing wings from pupae that were raised at 25°C, injected with BrdU at 16 hr APF, allowed to continue developing at 25°C until 36 hr APF, and then dissected and processed to visualize BrdU incorporation: (A) w (parental strain); (B) myb1. Bar, 0.05 mm.

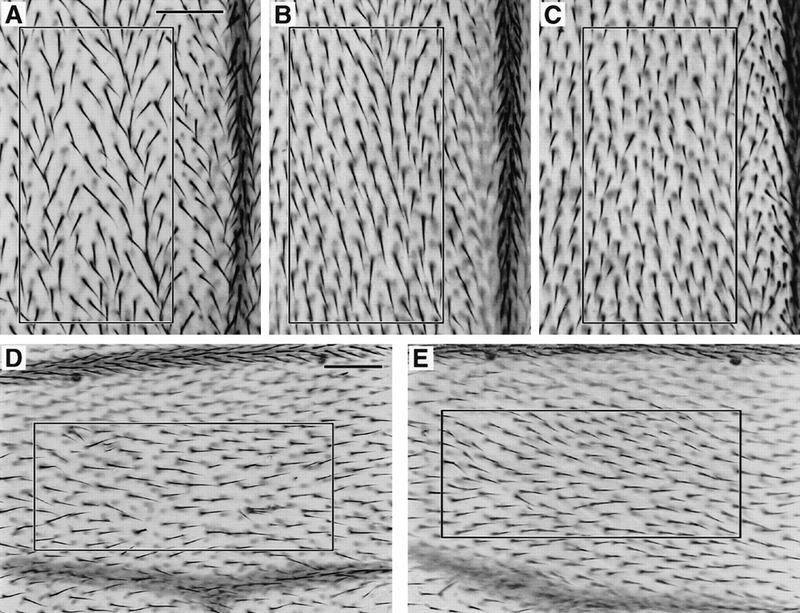

To assess further the cell cycle state of the mutant Dm myb wing cells, we tested whether the mutant phenotype could be suppressed by overexpression of either wild-type or activated alleles of Dm cdc2 (the cyclin-dependent kinase that regulates the G2/M transition) or string (the Drosophila homolog of cdc25, the protein tyrosine/threonine phosphatase that regulates cdc2 activity) (Edgar and O’Farrell 1990; O’Farrell 1992; Stern et al. 1993). Each of these transgenes, under the transcriptional control of the hsp70 heat shock promoter, was mated into strains carrying the mutant myb alleles. myb1 mutant pupae raised at 18°C were unable to tolerate the heat shock treatment and none survived to adulthood. myb2 mutant pupae raised at 25°C with or without each of the transgenes, were heat shocked when they were between 18 and 22 hr APF, and then allowed to continue development at 25°C. Overexpression of either cdc2 or string was able to partially suppress the myb2 wing phenotype, increasing the number of hairs by 30% to 35% (see Table 1) and correcting the orientation of the hairs (Fig. 5) Overexpression of these transgenes via heat shock treatment during the same stage of development had no effect on wings in the parental strain (not shown). These results support the conclusion that the mutant myb wing cells were arrested at the G2/M transition.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of Dm cdc2 or string during pupal development can suppress the mutant Dm myb wing defect. Wings were dissected from flies that were raised at 25°C, heat shock treated for 20 min at 37°C when they were between 18 and 22 hr APF, and then returned to 25°C. Bars in A and D, 0.05 mm. The number of hairs within the box in each panel is indicated below in parentheses. Shown in A–C at the same magnification is a region near the distal tip between longitudinal veins III and IV. When compared with myb2, overexpression of either Dm cdc2AF or stg in myb2 mutants resulted in an increase in the number of hairs in myb2 mutants: (A) myb2 (103 hairs); (B) myb2; HS–Dm cdc2AF/+ (135 hairs); (C) myb2; HS–stg/+ (134 hairs). The wild-type version of cdc2 under the heat shock promoter also suppressed the myb phenotype. To demonstrate that suppression occurred in multiple regions of the wing, a more proximal section is shown at a lower magnification: (D) myb2 (105 hairs); (E) myb2; HS–Dm cdc2/+ (137 hairs).

A subset of nuclei in myb mutants entered endoreduplication cycles

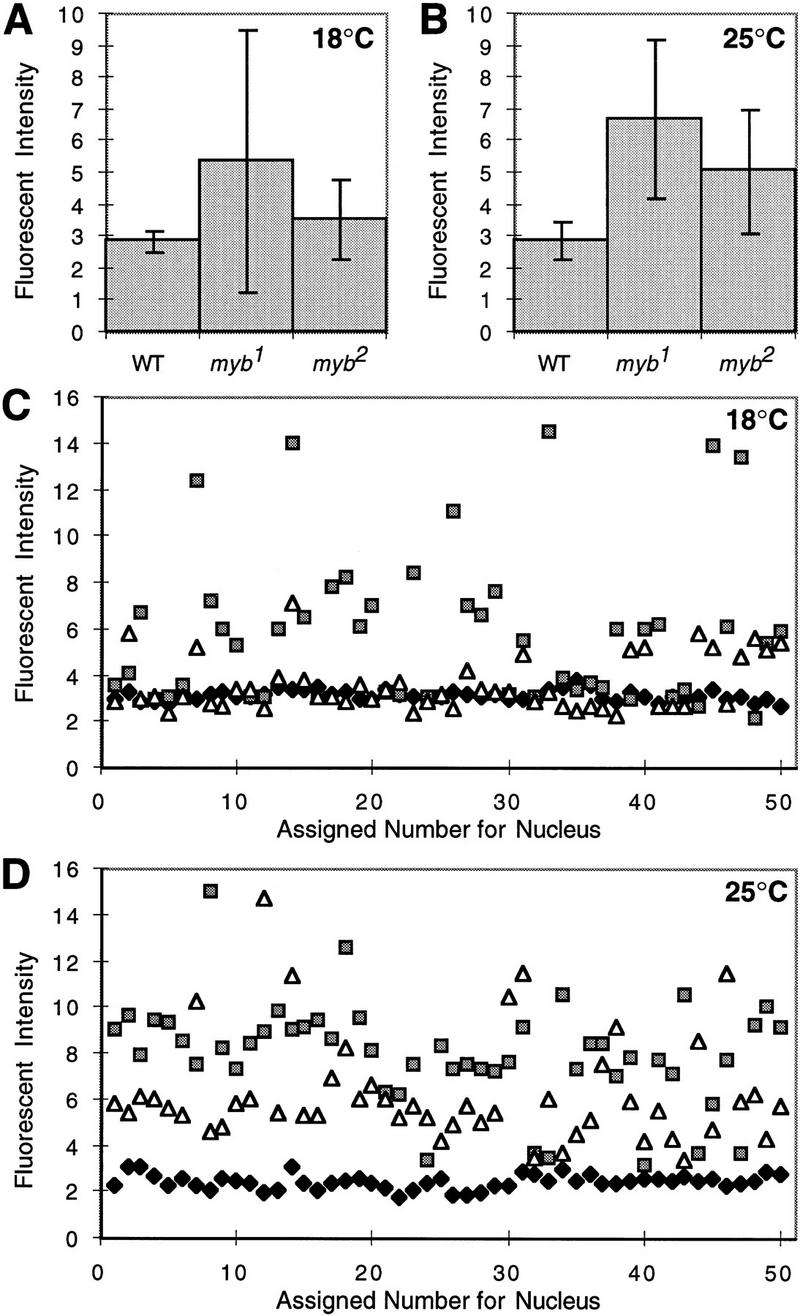

The results to this point suggested that the wing cells in mutant flies failed to complete the final mitosis in their developmental lineage. We explored this possibility further by using high-resolution, three-dimensional wide-field fluorescence microscopy to examine the amount of DNA contained in nuclei of individual wild-type and mutant cells (Fig. 6). Postmitotic wings from wild-type, myb1, and myb2 animals raised at 18°C (72 hr APF) or 25°C (36 hr APF) were dissected and fixed, and the DNA in the nuclei was stained with DAPI. Results from the analysis of 120 nuclei for each genotype and temperature are shown in Figure 6. At 18°C, the average DNA content of mutant myb1 nuclei was double that of wild-type nuclei, whereas the average for myb2 nuclei was only slightly elevated (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, the average DNA content of mutant myb1 nuclei was even greater at 25°C than at 18°C, and the average for myb2 nuclei increased to approximately double that of wild-type (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Quantitative microscopic analysis of nuclei from mutant and wild-type wings. Developing wings were dissected from wild-type (WT), myb1, and myb2 pupae at 72 hr AFP for animals raised at 18°C, or 36 hr APF for animals raised at 25°C. Wings were then fixed and stained with DAPI. Four samples from each genotype and temperature were optically sectioned using high-resolution, three-dimensional wide-field fluorescence microscopy (see Materials and Methods). Relative fluorescent intensities and volumes of at least 30 nuclei for each sample (⩾120/genotype) were analyzed. Shown are the calculated averages (means) of nuclear fluorescent intensities for each genotype at 18°C (A) and 25°C (B) with standard deviations indicated by vertical bars. To illustrate the heterogeneity within the population of mutant nuclei, the fluorescent intensities of 50 nuclei from each genotype at 18°C (C) and 25°C (D) are plotted individually. (Solid diamond) Wild-type; (shaded square) myb1; (open triangle) myb2.

As anticipated, the results indicated that the mutant cells generally contained more DNA than wild-type cells. But there was substantial heterogeneity in the data for mutant cells, first apparent as relatively large standard deviations for the measurements of DNA content (Fig. 6A,B). Analysis of the data for individual cells provided an explanation (Fig. 6C,D). At the semipermissive temperature of 18°C, the amount of DNA in myb1 nuclei varied from 2C to well in excess of 4C. At 25°C, the majority of nuclei contained more than 4C DNA. We conclude that the mutation causes endoreduplication in a fraction of the arrested wing cells, the severity of which varies from one cell to another.

Temperature shifts demonstrate a direct role for myb in the final cell cycle of the wing

It remained possible that the defective cell cycle associated with the Dm myb mutants was a secondary consequence rather than a primary effect of the deficiency in myb function. In an effort to explore this possibility, we performed temperature-shift experiments with myb2. Two factors facilitated this strategy: the temperature-dependent expressivity of myb2 within a viable range of temperatures (see above, Fig. 2G,I); and the well-defined window of time within which the final cell division occurs in the maturing wing (see above and Schubiger and Palka 1987). We could not perform this sort of analysis with myb1 because even at 18°C, the majority of cells do not undergo their final mitosis. Since shifting to restrictive temperature earlier in development (late third instar larval or prepupal stages) invariably results in lethality (Katzen and Bishop 1996), it was also not feasible to effect a block in the initial cell cycle of the emerging wing.

In myb2 mutants raised at 18°C, the majority of wing cells underwent the final mitosis and contained the normal complement of DNA (Fig. 6C), resulting in adult wings that contained 80% of the hairs found in wild-type wings (Table 1; Fig. 2G). In contrast, most of the wing cells in myb2 mutants raised at 25°C failed to complete their final cell cycle, resulting in adult wings that contained slightly more than half the number of hairs found in wild-type wings (Table 1; Fig. 2I), and cells that contained on average, twice the normal complement of DNA (Fig. 6B). When myb2 flies were transiently exposed to the higher temperature during the period of time corresponding to the final cell division, the number of wing cells was reduced to the maximum extent, that is, approximately one-half the normal number (Fig. 7; Table 1). We conclude that the failure of wing cells to complete the final cell division cycle is likely to be an immediate consequence of the deficiency in myb function.

Figure 7.

The mutant myb2 wing phenotype is enhanced by shifting from permissive to restrictive temperature for 1 day during pupal wing development. Bar in A, 0.05 mm. The number of hairs within the box in each panel is indicated below. Shown is a region near the distal tip between longitudinal veins IV and V. Wings were dissected from white flies that were raised at 18°C until 26 hr APF, transferred to 28°C for 24 hr, and then returned to 18°C, 222 hairs (A), myb2 flies that were raised continuously at 18°C, 178 hairs (B), or myb2 flies that were raised at 18°C until 26 hr APF, transferred to 28°C for 24 hr and then returned to 18°C, 115 hairs (C).

Discussion

Conservative changes in single amino acids are responsible for the mutant phenotypes of myb1 and myb2

Mutations in myb1 and myb2 arose from changes in single nucleotides that cause amino acid substitutions (Fig. 1). In myb1, serine replaces glycine in one of the four structural domains that are conserved among the myb loci of Drosophila and vertebrates. The fact that the relatively neutral change of serine to glycine engenders a mutant phenotype suggests a strong requirement for serine at the residue. Because the function of the mutant protein domain is not known, the apparent requirement for serine cannot presently be explained.

The mutation in myb2 substitutes lysine for arginine at a position within the DNA-binding domain of the DMyb protein, a conservative change that should not necessarily disrupt function. Arginine has been conserved at the comparable positions in the Myb, MybA, and MybB proteins of vertebrates (Gonda et al. 1985; Gerondakis and Bishop 1986; Majello et al. 1986; Nomura et al. 1988), and in the more distant Myb-related proteins from yeast and plants (Ohi et al. 1994). We conclude that the mutated arginine residue is essential to the function of Myb.

Insight into the role of the conserved arginine comes from examination of the manner in which Myb interacts with its specific target site in DNA. Ogata and colleagues have used nuclear magnetic resonance to analyze this interaction, using a complex between the isolated DNA-binding domain of mouse Myb and the DNA sequence to which it binds (Ogata et al. 1994). The DNA-binding domain of Myb is composed of three imperfect tandem repeats designated R1–R3 (Kanei-Ishii et al. 1996). The second and third of three repeats are required for DNA binding. Each repeat contains three helices, the third of which recognizes the target DNA sequence. Arg-177 in the Drosophila protein, the amino acid replaced by Lys in myb2, corresponds to Arg-133 in the mouse Myb protein. This arginine is in the middle of the recognition (third) helix of R2, and although it does not specifically interact with any of the base pairs of the target sequence, it does form a contact with the phosphate backbone and also interacts by a salt bridge with Asp-100 (Asp-144 in the Drosophila protein), interactions that presumably stabilize the protein–DNA complex. In addition, the third helix within R2 was shown to be thermally less stable than any other part of the DNA-binding domain (Ogata et al. 1994). Together, these findings provide an explanation for why the substitution of lysine for arginine results in a temperature-sensitive phenotype.

The wing phenotype is the consequence of a G2/M block and failure to prevent endoreduplication of DNA

Analysis of pupal wings during different stages of development showed that, for the mutant alleles of Dm myb in hand, wing development is apparently normal into early pupation, when cells are normally arrested in G2. Postmitotic wings in myb1 and myb2 mutants raised at semipermissive temperatures, however, have approximately half as many cells as wild-type wings. Since wild-type wing cells normally undergo two mitotic cleavages during pupal development, the majority of mutant cells must divide once. It seems likely that mutant myb cells progress through the first mitosis and are blocked during their final cell cycle. myb1 wing cells incorporate BrdU during the period corresponding to the final S phase, indicating that the block occurs after entry into DNA synthesis. This is supported by the fact that in mutant wings, the nuclei, cells, and hairs are all larger than in wild-type wings, an effect known to correlate with increased DNA content.

When overexpressed at the appropriate stage of pupal development, either of two key regulators of the G2/M transition, Dm cdc2 or string/cdc25, can at least partially suppress the wing defect. These results suggest that S phase has been completed and that the mutant cells are arrested in G2, as mitosis is generally dependent on the completion of DNA synthesis. In S. pombe, however, it has been shown that dependence of mitosis on DNA synthesis is lost in strains that either overproduce the cdc25 protein or carry mutations in cdc2 that make it independent of cdc25 activity (Enoch and Nurse 1990). In those strains, the abnormal divisions lead to disturbances in nuclear morphology and reduced cellular viability. We did not observe any signs of these cellular disturbances in our experiments. It appears that it is more difficult to overcome the dependence of mitosis on completion of DNA synthesis in Drosophila than in yeast, as overproduction of string/cdc25 in Drosophila embryos was unable to drive S-phase-arrested cells into mitosis, perhaps because the string protein is unstable prior to G2 (Edgar and Datar 1996; B.A. Edgar, pers. comm.). Therefore, we conclude that the wing cells in Dm myb mutants enter and complete DNA synthesis, but are blocked during G2 or at the G2/M transition. It is still possible, however, that although S phase is largely completed, a few replication forks are stalled and that at this late stage, overexpression of the G2/M regulators can overcome the S phase checkpoint.

High-resolution, three-dimensional wide-field fluorescence microscopy revealed heterogeneity within the population of mutant cells. In wings from myb1 and myb2 mutants raised at semipermissive temperatures, most nuclei contain twice the normal complement of DNA, but nuclei with the normal complement are also observed, suggesting that some of the cells, perhaps those that divide earliest, retain enough myb activity to complete the final division. We also found that many of the arrested cells continued to replicate their DNA. The extent of endoreduplication varied from one cell to another and was particularly pronounced in the wings of myb1 mutants raised at 25°C (nonpermissive for adult viability), at which temperature the majority of cells had DNA contents in excess of 4C. These results suggest that Dm myb normally acts to inhibit endoreduplication, a conclusion that is consistent with our previous findings that Dm myb is not expressed at detectable levels in polyploid larval tissues (Katzen and Bishop 1996). The endoreduplication also provides an explanation for why ectopic expression of cdc2 or string did not fully suppress the myb2 phenotype in the wing. Some of the cells may no longer have been capable of undergoing mitosis, as they had already begun to endocycle. Given recent reports that under certain circumstances, myb genes can play a role in regulating bcl-2 expression (Frampton et al. 1996; Taylor et al. 1996), we note that we did not detect any signs of apoptosis in mutant wings.

In adult wings from Dm myb mutants raised at permissive temperature, there was not only a reduction in the number of cells, but also a disturbance of tissue polarity as judged by hair orientation and presence of occasional small clusters of hairs protruding from a single position. This prompts the question of whether the defects in cell cycle and polarity are independent of each other or whether one is an indirect consequence of the other. Because regulators of the G2/M transition suppress both defects (see above and Fig. 5), it seems likely that the polarity defects are an indirect result of the abnormal cell cycle stage in which the wing cells are trapped. In support of this, when mitotic clones of cdc2 mutations were induced in wings, cells with multiple hairs and abnormal polarity were observed (P.N. Adler, pers. comm.).

On the basis of our studies, two cell cycle checkpoints appear to be disturbed in the wing cells of Dm myb mutants: regulation of the G2/M transition and prevention of re-entry into S phase before M phase occurs. Is one of these defects a consequence of the other or are they independent of each other? In string mutant embryos, cells arrest at the G2/M boundary and do not enter S phase (Edgar and O’Farrell 1989; Smith and Orr-Weaver 1991), indicating that the mechanism for preventing reinitiation of DNA replication before mitosis can remain intact when cells are prematurely arrested in G2. Therefore, it is unlikely that the endoreduplication in mutant myb cells is simply a consequence of the abnormal arrest in G2. Because overexpression of either Dm cdc2 or string can partially suppress the myb phenotype, at least a proportion of the mutant cells must still be competent for mitosis, suggesting that the block in G2 is not just a consequence of the mutant cells entering into an endocycle and losing the ability to divide. We conclude that myb may play active and independent roles in both checkpoints.

Is Dm myb function required in all cell cycles?

The studies reported here focus on the cellular basis of the wing defect. We have reason to believe, however, that Dm myb plays a more general role in cell cycle regulation, as we have observed a variety of other cells that appear to be affected in a fashion similar to the wing cells (fewer cells, larger nuclei). Of particular note is a subset of glial cells, identified by staining with a glial-specific antibody (Campbell et al. 1994). We suspect that the defects in these cells may be responsible for the inviability of myb mutants at restrictive temperatures (A.L. Katzen et al., unpubl.). In addition, abdominal cuticular defects are observed in myb mutants raised at semipermissive temperatures (A.L. Katzen et al., unpubl.), which are similar to other mutant phenotypes that result from a shortage of adult epidermal cells to replace larval epidermal cells (escargot and cdc2; Hayashi et al. 1993; Stern et al. 1993). There are, however, cell types that appear to be normal, even at restrictive temperature, and in the wings, the cells are blocked from completing only their final cell cycle.

Do these results necessarily mean that Dm myb is not required for all cell types and cell cycles? We suspect that this is not the case. Because Dm myb is expressed at relatively high levels in most proliferating cells and both of the mutant alleles are hypomorphic and temperature sensitive (Katzen and Bishop 1996), it seems likely that enough myb activity is present in most mutant cells for them to divide. The phenotype observed in the wing supports this possibility, as the developing mutant wings appear normal until the final cell cycle, which occurs during a period (12–24 APF) when the level of Dm myb message is decreasing. Of course, it is possible that Dm myb function is required for cell division in some tissues and not in others, even though the gene is expressed in all mitotic tissues. In this case, we would have to conclude that Dm myb expression in unaffected tissues is either gratuitous or functionally redundant with another gene. Final determination of whether myb function is required in all cell cycles will have to await generation of stronger alleles of myb.

Regulatory pathways in which myb may participate

The biochemical pathways that regulate the G2/M transition and ensure the maintenance of diploidy are likely to be complex. Dm myb is not the only gene that has been implicated in both of these regulatory checkpoints. Two other genes, Dm cdc2 and Dm cyclin A, which play critical roles in regulating the G2/M transition, have recently been shown to suppress endoreduplication (Sauer et al. 1995; Hayashi 1996). In Dm cdc2 mutants, the abdominal histoblasts, which are normally arrested in G2 during larval development, undergo endoreduplication instead, indicating that endoreduplication can be decoupled from premature mitotic arrest (Hayashi 1996). Hayashi also provided evidence that, unlike the G2/M transition, which is initiated by the dephosphorylated, kinase-active form of Cdc2, endoreduplication is inhibited by the phosphorylated (kinase-inactive) form, probably complexed with cyclin A. Consistent with the ability of Drosophila cdc2, cyclin A, and myb to prevent re-entry into S-phase before mitosis occurs, none of these genes are expressed in polyploid tissues (Lehner and O’Farrell 1989, 1990; Stern et al. 1993; Katzen and Bishop 1996).

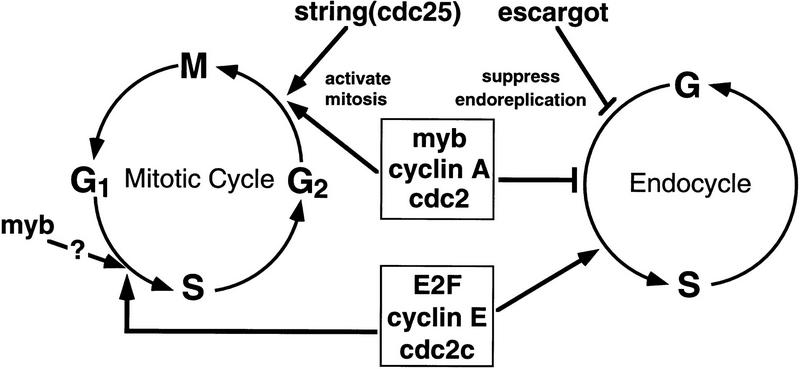

We hypothesize that Dm myb participates along with Dm cdc2 and Dm cyclin A in the biochemical circuit that regulates both the G2/M transition and maintenance of diploidy. This hypothesis is supported by the ability of Dm cdc2 to suppress the myb wing phenotype, when overexpressed at the appropriate time. Not surprisingly, there are other genes such as string and escargot, that function to regulate either the G2/M transition or suppression of endoreduplication, respectively, but not both (Edgar and O’Farrell 1989; Smith and Orr-Weaver 1991; Hayashi 1996). An illustration of some of the key players that regulate the mitotic and endoreplicative cells cycles is shown in Figure 8. There is little doubt that many other genes participate in regulating one or both of these cell cycles, and it is likely that some of them will be subject to transcriptional regulation by myb. Genetic screens designed to isolate suppressors and/or enhancers of the mutant Dm myb phenotype should allow us to identify genes that participate in the same biochemical pathways as myb. We have preliminary data demonstrating a strong genetic interaction between Drosophila myb and cyclin A, but the biochemical basis of this interaction is not yet known (A.L. Katzen et al., unpubl.).

Figure 8.

Schematic of gene products known to play key roles in regulating the mitotic and endoreplicative cell cycles. The data presented in this paper demonstrate that Dm myb is a positive regulator of progression from G2 into M and a negative regulator of endoreduplication, thereby maintaining diploidy. These dual functions are shared with Dm cdc2 and Dm cyclin A (Sauer et al. 1995; Hayashi 1996). In contrast, string and escargot, function to either activate the G2/M transition or suppress endoreduplication, respectively, but not both (Edgar and O’Farrell 1989; Smith and Orr-Weaver 1991; Hayashi 1996). The transcription factor E2F, Dm cyclin E, and the Dm cdc2c kinase are required for S phase in both mitotic and endoreplicative cell cycle (Duronio et al. 1995; Sauer et al. 1995; Lilly and Spradling 1996). By analogy to the role that vertebrate myb genes are thought to play in cell cycle regulation, Dm myb may also participate in regulation of the G1/S transition, but our studies indicate that it is not required for DNA synthesis in endocycling cells.

Is the role of myb in cell cycle regulation evolutionarily conserved?

Our finding that a mutation in Dm myb leads to a cell cycle block superficially agrees with several lines of evidence that vertebrate c-myb is required for proliferation in at least a subset of cell types (Mucenski et al. 1991; Badiani et al. 1994; Lyon et al. 1994; Thompson and Ramsay 1995). In contrast to our results in Drosophila, vertebrate myb genes are generally thought to be involved in regulating the G1/S transition (for review, see Lyon et al. 1994), but the most direct evidence for this has recently been challenged (see introductory section).

Could Dm myb also be involved in regulating the G1/S transition? Since a reduction in myb activity leads to inappropriate endoreduplication, it seems unlikely that Dm myb function is required for DNA synthesis, as such. This conclusion is also supported by previous observations that Dm myb transcripts are not detectable in polyploid tissues (Katzen and Bishop 1996) and by our studies of mutants during larval and pupal development, in which no defects in endoreduplication were found (not shown).

Regulation of entry into S phase, however, clearly differs between endoreplicating and mitotically proliferating cells (Smith and Orr-Weaver 1991; Orr-Weaver 1994; Sauer et al. 1995; Lilly and Spradling 1996). Therefore, it is possible that Dm myb might play a role in the G1/S transition in the mitotic cell cycle, even though it does not appear to be required for replication in endocycling cells. As noted above, Dm myb is expressed at relatively high levels in most proliferating cells. If Dm myb were required at lower levels for the G1/S transition than for G2/M, then the hypomorphic myb alleles might retain sufficient activity for efficient progression into S, leaving the phenotype to manifest itself at the G2/M transition.

Whatever, its role in the G1/S transition, there are reasons to suspect that vertebrate myb may also act later in the cell cycle. Although expression of both c-myb and B-myb are specifically induced at the G1/S boundary in many cell types, expression levels remain high throughout S phase (Lyon et al. 1994). B-myb has also been shown to be a target for transcriptional regulation by the E2F transcription factor (DeGregori et al. 1995; Zwicker et al. 1996). E2F controls a variety of genes encoding proteins required for G1/S (e.g., cyclin E), S-phase (e.g., DNA polymerase α), and G2–G2/M transition (e.g., cyclin A and cdc2). Of these genes, the manner in which B-myb is negatively regulated by E2F appears to be most similar to that of cyclin A and cdc2 (Bennett et al. 1996; Liu et al. 1996; Hurford et al. 1997). Finally, ectopic expression of B-myb or c-myb in cell culture induces cdc2 expression (Sala and Calabretta 1992; Ku et al. 1993). It is therefore tempting to speculate that in Drosophila, E2F may regulate expression of myb, which in turn regulates one or more of the genes that control the G2/M transition and suppression of endoreduplication (e.g., cdc2, string, cyclin A).

Many myb-related genes have now been identified in organisms that diverged earlier in evolution than Drosophila, such as yeast and plants (Paz-Ares et al. 1987; Tice-Baldwin et al. 1989; Ohi et al. 1994). Only one of these, the S. pombe cdc5 gene, has been shown to be involved in regulating the cell cycle, having been implicated in the G2 phase of the cell cycle (Ohi et al. 1994). Our data demonstrate that a myb gene can also function to regulate the G2/M transition in a multicellular organism. In addition, we have identified a novel activity for myb in inhibiting endoreduplication. These results indicate an ancient role for the Myb transcription factor in regulating cell cycle checkpoints other than the G1/S transition and raise the possibility that one or more of the vertebrate myb genes may have similar functions in cell cycle regulation.

Materials and methods

Sequence analysis of mutant alleles

Because myb1 and myb2 are temperature-sensitive alleles, both mutants could be maintained as homozygotes. Genomic DNA was prepared from each mutant and the parental white strain as described previously (Katzen et al. 1985). Six pairs of oligonucleotides were used to PCR amplify three overlapping segments that span the entirety of the Dm myb gene. The oligonucleotides were designed to introduce restriction enzyme sites at the ends of the amplified fragments so that they could be cloned easily into the vector pGEM-7Zf (Promega). The same oligonucleotides (without the added sequences used to create restriction enzymes sites) and additional oligonucleotides corresponding to sequences internal to the fragments, were used for sequencing. The US Biochemical kit (dideoxy [35S]dATP) was used to sequence 4–5 μg of denatured, cesium chloride-banded DNA, which was run on gels using Long Ranger gel mix from AT Biochem. Discrepancies in sequences obtained from clones representing the mutant alleles were checked and confirmed by sequencing both strands. For myb1 and myb2, two or three independent PCR-amplified clones were sequenced, respectively. In the case of myb1, an EcoRI fragment spanning the mutation was cloned directly from genomic DNA into the pGEM-7Zf vector. Sequencing of this clone also confirmed the presence of the mutation.

Drosophila stocks

Generation of mutant Dm myb alleles on a white chromosome, construction of lines carrying a wild-type Dm myb rescue transgene, P(w+,myb+) and the Df(1)sd72b26 chromosome, which deletes a region that includes Dm myb have been described previously (Katzen and Bishop 1996). Transgenic lines carrying either the heat shock (HS)–string, HS–Dm cdc2, or the HS–Dm cdc2AF construct were generously provided by Patrick O’Farrell (University of California at San Francisco; Edgar and O’Farrell 1990; Stern et al. 1993). The Dm cdc2AF is an allele of cdc2 that has an alanine substituted for threonine-14 and a phenylalanine substituted for tyrosine-15, which prevents these two positions from being phosphorylated and makes the kinase activity of the protein string independent (Krek and Nigg 1991).

Preparation and fluorescent staining of wings

Adult wings were dissected from flies in isopropanol and mounted with a water-soluble mounting media (Immu-mount, Shandon). Photomicroscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axiophot microscope.

Pupae were staged by transfer of white prepupae (0 hr APF) from healthy bottles maintained at the appropriate temperature to fresh vials and further development at the same temperature. Wing disks and the central nervous system (brain/ventral ganglia) from third instar larvae and prepupae (6 hr APF, 25°C or 13 hr APF, 18°C) were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (130 mm sodium chloride, 10 mm phosphate at pH 6.8) plus 0.1% Tween (PBST) and fixed for 30–60 min in PBST containing 4% paraformaldehyde, which had been freshly prepared. After being washed at least three times in PBST, wings were incubated for 20 min in the dark in a PBST solution containing 1 μg/ml DAPI. Wings were washed several times in PBST. A drop of glycerol was added to the final rinse solution, and the wings were stored overnight at 4°C in the dark before being mounted in Immu-mount (Shandon). For later stages, a tungsten needle was used to puncture the head of each pupa, which was then put into a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube containing the same fixation solution as above. After several hours on a rocker, pupae were rinsed and dissected in PBST. The pupal cuticle was gently teased off of each wing. Wings were incubated for 20 min in the dark in a PBST solution containing 5 U/ml rhodamine-labeled phalloidin (Molecular Probes), washed at least three times in PBST, and then stained with DAPI and prepared for mounting as described above. Fluorescence photomicroscopy was performed with a Zeiss Photomicroscope III.

Application of BrdU

Pupae raised at 25°C were selected and aged as described above. They were then injected with BrdU (from Amersham’s cell proliferation kit, code RPN 20) at either 12–13 or 15–16 hr APF according to the method described by Hartenstein and Posakony (1989) and incubated in a humid chamber at 25°C until 36 hr APF. At this time point, the wings were dissected, fixed in modified Carnoy’s fixative [100% ethanol/glacial acetic acid (3:1)], and rinsed several times in PBST. Further processing was according to the instructions of the kit, with the only modification being that 0.1% Tween was included in all solutions. Photomicroscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axiophot microscope.

High-resolution three-dimensional fluorescence microscopy of developing wings

Pupal wings were prepared from wild-type (parental strain) and myb1 and myb2 mutants at either 36 hr APF for flies raised at 25°C or 72 hr APF for flies raised at 18°C by the protocol described above, except for the following modifications: Wings were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde prepared in buffer A (15 mm Pipes, 80 mm KCl, 20 mm NaCl, 2 mm Na2EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 0.5 mm spermidine, 0.2 mm spermine) plus 0.1% Tween. After DAPI staining and three rinses in the dark, wings were immediately mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Inc.), a mounting media that inhibits fading of the fluorescent signal, and cover slips were sealed with clear nail polish. For each genotype and temperature, four samples (two samples each from two different wings mounted under the same cover slip) were examined. Three-dimensional data sets were collected from all wings on the same day (stained wings were kept in the dark when not being analyzed), by use of an Olympus 60× 1.4 N.A. oil immersion lens on a computer controlled wide-field microscopy system and cooled CCD camera as described elsewhere (Hiraoka et al. 1991). Cells were imaged in three dimensions by movement of the sample through the focal plane of the objective lens at 0.5-μm increments and recording of an image with the CCD camera at each position. Out-of-focus light was removed by a constrained iterative deconvolution algorithm using an empirical point-spread function (Agard et al. 1989; Hiraoka et al. 1990). Processed data presented here were examined and manipulated by use of the IVE software package developed for three-dimensional images, which allowed individual nuclei to be selected and modeled interactively with a graphical user interface (Chen et al. 1996). For each data set, a minimum of 30 nuclei were selected for analysis (for a total of ⩾120/genotype). After three-dimensional modeling, the integrated fluorescent intensity and volume for each nucleus was calculated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nikita Yakubovich and Patrick O’Farrell for supplying the Drosophila strains carrying HS-cdc2, HS-cdc2AF, and HS-string constructs; Bruce Edgar and Paul Adler for sharing unpublished results; Sergei Mirkin, Tom Kornberg, and Patrick O’Farrell for useful discussion and advice; John Sedat for support and advice on quantitative three-dimensional fluorescence microscopy. Work reported here was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant CA44338), by funds from the G.W. Hooper Research Foundation, and by a Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Research Award (5-FY97-0050) from the March of Dimes to A.L.K. B.P.H. was supported by a National Science Foundation predoctoral fellowship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL katzen@uic.edu; FAX (312) 413-0353.

References

- Adler PN. The genetic control of tissue polarity in Drosophila. BioEssays. 1992;14:735–741. doi: 10.1002/bies.950141103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agard DA, Hiraoka Y, Shaw P, Sedat JW. Fluorescence microscopy in three dimensions. Methods Cell Biol. 1989;30:353–377. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60986-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badiani P, Corbella P, Kioussis D, Marvel J, Weston K. Dominant interfering alleles define a role for c-Myb in T-cell development. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:770–782. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JD, Farlie PG, Watson RJ. E2F binding is required but not sufficient for repression of B-myb transcription in quiescent fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1996;13:1073–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedenkapp H, Borgmeyer U, Sippel AE, Klempnauer KH. Viral myb oncogene encodes a sequence-specific DNA-binding activity. Nature. 1988;335:835–837. doi: 10.1038/335835a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop JM, Eilers M, Katzen AL, Kornberg T, Ramsay G, Schirm S. MYB and MYC in the cell cycle. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1991;56:99–107. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1991.056.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess TL, Fisher EF, Ross SL, Bready JV, Qian YX, Bayewitch LA, Cohen AM, Herrera CJ, Hu SS, Kramer TB, et al. The antiproliferative activity of c-myb and c-myc antisense oligonucleotides in smooth muscle cells is caused by a nonantisense mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:4051–4055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabretta B. Inhibition of protooncogene expression by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides: Biological and therapeutic implications. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4505–4510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G, Goring H, Lin T, Spana E, Andersson S, Doe CQ, Tomlinson A. RK2, a glial-specific homeodomain protein required for embryonic nerve cord condensation and viability in Drosophila. Development. 1994;120:2957–2966. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Hughes D, Chan T-A, Sedat JW, Agard DA. IVE (Image Visualization Environment): A software platform for all three-dimensional microscopy applications. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:56–60. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGregori J, Kowalik T, Nevins JR. Cellular targets for activation by the E2F1 transcription factor include DNA synthesis- and G1/S-regulatory genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4215–4224. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duronio RJ, O’Farrell PH, Xie JE, Brook A, Dyson N. The transcription factor E2F is required for S phase during Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1445–1455. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar BA, Datar SA. Zygotic degradation of two maternal Cdc25 mRNAs terminates Drosophila’s early cell cycle program. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1966–1977. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.15.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar BA, O’Farrell PH. Genetic control of cell division patterns in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1989;57:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90183-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— The three postblastoderm cell cycles of Drosophila embryogenesis are regulated in G2 by string. Cell. 1990;62:469–480. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch T, Nurse P. Mutation of fission yeast cell cycle control genes abolishes dependence of mitosis on DNA replication. Cell. 1990;60:665–673. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frampton J, Ramqvist T, Graf T. v-Myb of E26 leukemia virus up-regulates bcl-2 and suppresses apoptosis in myeloid cells. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:2720–2731. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerondakis S, Bishop JM. Structure of the protein encoded by the chicken proto-oncogene c-myb. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3677–3684. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda TJ, Gough NM, Dunn AR, de Blaquiere J. Nucleotide sequence of cDNA clones of the murine myb proto-oncogene. EMBO J. 1985;4:2003–2008. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03884.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda TJ, Favier D, Ferrao P, Macmillan EM, Simpson R, Tavner F. The c-myb negative regulatory domain. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;211:99–109. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85232-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein V, Posakony JW. Development of adult sensilla on the wing and notum of Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 1989;107:389–405. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S. A Cdc2 dependent checkpoint maintains diploidy in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:1051–1058. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.4.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Hirose S, Metcalfe T, Shirras AD. Control of imaginal cell development by the escargot gene of Drosophila. Development. 1993;118:105–115. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka Y, Sedat JW, Agard DA. Determination of 3-dimensional imaging properties of a light microscope system—partial confocal behavior in epifluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 1990;57:325–333. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82534-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka Y, Swedlow MR, Paddy MR, Agard DA, Sedat JW. Three-dimensional multiple-wavelength fluorescence microscopy for the structural analysis of biological phenomena. Semin Cell Biol. 1991;2:153–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurford R, Jr, Cobrinik D, Lee MH, Dyson N. pRB and p107/p130 are required for the regulated expression of different sets of E2F responsive genes. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:1447–1463. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzen AL, Bishop JM. myb provides an essential function during Drosophila development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:13955–13960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzen AL, Kornberg TB, Bishop JM. Isolation of the proto-oncogene c-myb from D. melanogaster. Cell. 1985;41:449–456. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanei-Ishii C, Nomura T, Ogata K, Sarai A, Yasukawa T, Tashiro S, Takahashi T, Tanaka Y, Ishii S. Structure and function of the proteins encoded by the myb gene family. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;211:89–98. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-85232-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krek W, Nigg EA. Mutations of p34cdc2 phosphorylation sites induce premature mitotic events in HeLa cells: Evidence for a double block to p34cdc2 kinase activation in vertebrates. EMBO J. 1991;10:3331–3341. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku DH, Wen SC, Engelhard A, Nicolaides NC, Lipson KE, Marino TA, Calabretta B. c-myb transactivates cdc2 expression via Myb binding sites in the 5′- flanking region of the human cdc2 gene. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2255–2259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner CF, O’Farrell PH. Expression and function of Drosophila cyclin A during embryonic cell cycle progression. Cell. 1989;56:957–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90629-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Drosophila cdc2 homologs: A functional homolog is coexpressed with a cognate variant. EMBO J. 1990;9:3573–3581. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07568.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly MA, Spradling AC. The Drosophila endocycle is controlled by cyclin E and lacks a checkpoint ensuring S-phase completion. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:2514–2526. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Lucibello FC, Zwicker J, Engeland K, Muller R. Cell cycle-regulated repression of B-myb transcription: Cooperation of an E2F site with a contiguous corepressor element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2905–2910. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.15.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon J, Robinson C, Watson R. The role of Myb proteins in normal and neoplastic cell proliferation. Crit Rev Oncogenesis. 1994;5:373–388. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v5.i4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majello B, Kenyon LC, Dalla-Favera R. Human c-myb protooncogene: Nucleotide sequence of cDNA and organization of the genomic locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986;83:9636–9640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan AD. Tests for comparing related amino-acid sequences. Cytochrome c and cytochrome c 551. J Mol Biol. 1971;61:409–424. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucenski ML, McLain K, Kier AB, Swerdlow SH, Schreiner CM, Miller TA, Pietryga DW, Scott W, Jr, Potter SS. A functional c-myb gene is required for normal murine fetal hepatic hematopoiesis. Cell. 1991;65:677–689. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90099-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura N, Takahashi M, Matsui M, Ishii S, Date T, Sasamoto S, Ishizaki R. Isolation of human cDNA clones of myb-related genes, A-myb and B-myb. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:11075–11089. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.23.11075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell PH. Cell cycle control: Many way to skin a cat. Trends Cell Biol. 1992;2:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90034-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata K, Morikawa S, Nakamura H, Sekikawa A, Inoue T, Kanai H, Sarai A, Ishii S, Nishimura Y. Solution structure of a specific DNA complex of the Myb DNA-binding domain with cooperative recognition helices. Cell. 1994;79:639–648. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90549-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi R, McCollum D, Hirani B, Den Haese GJ, Zhang X, Burke JD, Turner K, Gould KL. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc5+ gene encodes an essential protein with homology to c-Myb. EMBO J. 1994;13:471–483. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr-Weaver TL. Developmental modification of the Drosophila cell cycle. Trends Genet. 1994;10:321–327. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Ares J, Ghosal D, Wienand U, Peterson PA, Saedler H. The regulatory c1 locus of Zea mays encodes a protein with homology to myb proto-oncogene products and with structural similarities to transcriptional activators. EMBO J. 1987;6:3553–3558. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CW, Sippel AE, Vingron M, Klempnauer KH. Drosophila and vertebrate myb proteins share two conserved regions, one of which functions as a DNA-binding domain. EMBO J. 1987;6:3085–3090. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwait JH. Clonal analysis of Drosophila cuticular patterns. In: Ashburner M, Wright TRF, editors. The genetics and biology of Drosophila. 2c. London, UK: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 359–441. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C, Light Y, Groves R, Mann D, Marias R, Watson R. Cell-cycle regulation of B-Myb protein expression: Specific phosphorylation during the S phase of the cell cycle. Oncogene. 1996;12:1855–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala A, Calabretta B. Regulation of BALB/c 3T3 fibroblast proliferation by B-myb is accompanied by selective activation of cdc2 and cyclin D1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:10415–10419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer K, Knoblich JA, Richardson H, Lehner CF. Distinct modes of cyclin E/cdc2c kinase regulation and S-phase control in mitotic and endoreduplication cycles of Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1327–1339. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.11.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubiger M, Palka J. Changing spatial patterns of DNA replication in the developing wing of Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1987;123:145–153. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90436-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AV, Orr-Weaver TL. The regulation of the cell cycle during Drosophila embryogenesis: The transition to polyteny. Development. 1991;112:997–1008. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.4.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern B, Ried G, Clegg NJ, Grigliatti TA, Lehner CF. Genetic analysis of the Drosophila cdc2 homolog. Development. 1993;117:219–232. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D, Badiani P, Weston K. A dominant interfering Myb mutant causes apoptosis in T cells. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:2732–2744. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MA, Ramsay RG. Myb: An old oncoprotein with new roles. BioEssays. 1995;17:341–350. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice-Baldwin K, Fink GR, Arndt KT. BAS1 has a Myb motif and activates HIS4 transcription only in combination with BAS2. Science. 1989;246:931–935. doi: 10.1126/science.2683089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauth K, Mutschler B, Jenkins NA, Gilbert DJ, Copeland NG, Klempnauer KH. Mouse A-myb encodes a trans-activator and is expressed in mitotically active cells of the developing central nervous system, adult testis and B lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1994;13:5994–6005. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston K, Bishop JM. Transcriptional activation by the v-myb oncogene and its cellular progenitor, c-myb. Cell. 1989;58:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong LL, Adler PN. Tissue polarity genes of Drosophila regulate the subcellular location for prehair initiation in pupal wing cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:209–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker J, Liu N, Engeland K, Lucibello FC, Muller R. Cell cycle regulation of E2F site occupation in vivo. Science. 1996;271:1595–1597. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]