Abstract

Integrin alpha-4 beta-1 (alpha4 beta1, alpha(4)beta(1), α4β1) is an attractive but poorly understood target for selective diagnosis and treatment of T and B cell lymphomas. This report focuses on the rapid microwave preparation, structure-activity relationships and biological evaluation of medicinally pertinent benzimidazole heterocycles as integrin α4β1 antagonists. We documented tumor uptake of derivatives labelled with I-125 in xenograft murine models of B-cell lymphoma. Molecular homology models of integrin α4β1 predicted that docked halobenzimidazole carboxamides have the halogen atom in a suitable orientation for halogen-hydrogen bonding. The high affinity halogenated ligands identified offer attractive tools for medicinal and biological use, including fluoro and iodo derivatives with potential radiodiagnostic (18F) or radiotherapeutic (131I) applications, or chloro and bromo analogues that could provide structural insights into integrin-ligand interactions through photoaffinity, cross-linking/mass spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallographic studies.

Keywords: α4β1 integrin, benzimidazole, radiolabeling, medicinal chemistry, lymphoma

Introduction

Current cancer chemotherapeutic agents aim to annihilate tumors through mechanisms such as DNA alkylation, unnatural base-pair recognition, inhibition of topoisomerases, and microtubule stabilization mechanisms. However, these agents, have a narrow therapeutic index, are administered near their maximum tolerated dose (MTD), and are largely non-discriminatory in recognizing either normal or cancerous cells. As a consequence, patients suffer from serious side effects including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, neuropathy, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hair loss, anemia, and various organ toxicities. While significant effort has been directed through lengthy syntheses of complex cytotoxic natural products, it is not until recent years that attention has been focused towards target-selective chemotherapeutics that could reduce off-target binding and ensuing side effects (1).

The resting or activated conformations of α4β1 integrin allow for the application of target-selective agents for malignant lymphoid cancers; activated α4β1 integrin is expressed on leukemias, lymphomas, melanomas, and sarcomas (2,3). Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptor proteins crucial for cell-cell, cell-matrix, and cell-pathogen interactions (4). Integrin α4β1 plays an important role in autoimmune diseases and inflammation (5), as well as tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis (6–11). Indeed, α4β1 integrin facilitates tumor cell extravasation (6), prevents apoptosis of malignant B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells (7), is key to drug resistance in both multiple myeloma and acute myelogenous leukemia (8), and has been selectively targeted with peptidomimetics (3, 13–17). Nonetheless, α4β1 integrin has not garnered much attention as either a therapeutic or a diagnostic cancer target due to the lack of potent and specific agents.

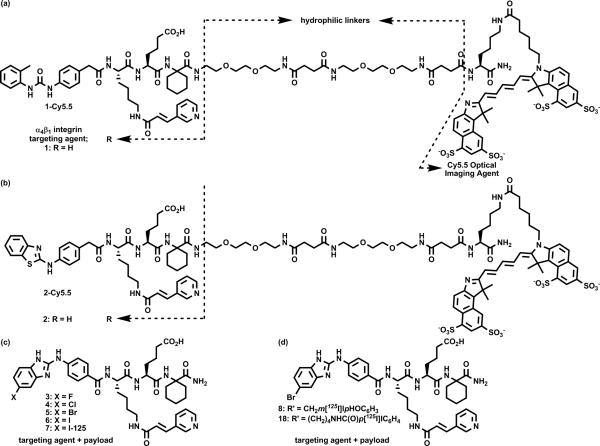

In accords with our program to discover potent and selective ligands that target various cancers, we have developed two in vivo imaging agents that have been successful in murine models (3, 13–18). Figures 1a and 1b shows the structure of these agents; the bisaryl urea 1-Cy5.5 (LLP2A-Cy5.5; Fig 1a; Ref. 3 and 15) and the benzothiazole analogue 2-Cy5.5 (KLCA14-Cy5.5; Fig. 1b; Ref. 16) both showed high affinity and specificity for B- and T-cell lymphomas containing activated α4β1 integrin, with the latter showing improved tumor:kidney signal. This is likely due to the improved solubility of 2-arylamino azole heterocycle (14, 16) over the bisaryl urea as these heterocycles have a lower logP, a higher dipole moment, and an increased acidity of the 2-arylamino N-H (pKa = 5.5–6.5; Ref. 19). However, both 1-Cy5.5 and 2-Cy5.5 have approximately one third of the molecular weight committed to the α4β1 integrin-targeting motif with the rest of the molecular weight devoted to the linker and the dye. Furthermore, due to the limited range of tissue penetration, optical imaging is not practical for whole-body imaging in human. There is a need to develop a condensed α4β1 integrin radio-targeting agent that not only can be used for PET and SPECT imaging but also for radiotherapy. With efforts integrating heterocyclic chemistry, cell adhesion assays, molecular modeling, and radiochemistry, we report herein the discovery of the bromobenzimidazole carboxamide 5 (IC50 = 115 pM), the structure-activity relationship (SAR) between halobenzimidazole carboxamides 3–6, and the biological evaluation of radio-iodinated derivates 7, 8 and 18 (structures shown in Figures 1c and 1d).

Figure 1.

Structures of: (a) 1-Cy5.5 (Ref. 3), (b) 2-Cy5.5 (Ref. 16), (c) halobenzimidazole analogues 3–7, and (d) the bishalo analogue 8 and 18 which incorporate the bromobenzimidazole moiety and a distal radioiodide.

Materials and Methods

Chemical synthesis

Compounds 3–9, 11–13, and 16–17 were synthesized as outlined in Supplementary Schemes 1–4. Compounds 1–2 (as well as 1-Cy5.5 and 2-Cy5.5), 9, 14, and 15a–b were previously reported (3, 14, 16, 20). The synthesis of 3–6 was analogous to our previous work (16), however the analytical data for these compounds is listed below. The synthesis of 7–8, 10–13, and 16–21 is described below.

(S)-6-(1-Carbamoylcyclohexyl-amino)-5-[(S)-2-{4-(5-fluoro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)amino)-benzamido]-6-[(E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl-acrylamido}hexanamido]-6-oxo-hexanoic Acid (3)

Following our procedure for benzimidazole analogues (16) afforded 3 as a white solid (10 mg, 44%): ESI-MS (m/z) 798.8 (M+H)+, ESI-HRMS for C41H49FN9O7 (M+H)+: Calcd, 798.3733; found, 798.4481 (m/z). Purity was determined to be 96% as determined by analytical HPLC.

(S)-6-(1-Carbamoylcyclohexylamino)-5-[(S)-2-{4-(5-chloro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)-benzamido]-6-[(E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)acrylamido}hexanamido]-6-oxo-hexanoic Acid (4)

Following our procedure for benzimidazole analogues (16) afforded 4 as a white solid (22 mg, 57%): ESI-MS 814.3, 816.3 (m/z) (M+H)+, ESI-HRMS for C41H49ClN9O7 (M+H)+: calcd, 814.3438 found, 814.2894 (m/z). Purity (HPLC): 96%.

(S)-5-[(S)-2-{4-(5-Bromo-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino}benzamido]-6-[(E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)-acrylamido}hexanamido]-6-(1-carbamoylcyclohexylamino)-6-oxo-hexanoic Acid (5)

Following our procedure for benzimidazole analogues (16) afforded 5 as a white solid (28 mg, 39%): ESI-MS (m/z) 858.4, 860.6 (M+H)+, ESI-HRMS for C41H49BrN9O7 (M+H)+: calcd, 906.2794; found, 906.2843 (m/z). Purity (HPLC): 99%.

(S)-6-(1-Carbamoylcyclohexylamino)-5-[(S)-2-{4-(5-iodo-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)benz-amido]-6-[(E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)acrylamido}hexanamido]-6-oxohexanoic Acid (6)

Following our procedure for benzimidazole analogues (16) afforded 6 as a white solid (18 mg, 48%): ESI-MS 906.3 (m/z) (M + H)+, ESI-HRMS for C41H49IN9O7 (M + H)+: Calcd, 906.2794; Found, 906.2843 (m/z). Purity (HPLC): 96%.

[125I]-(S)-6-(1-Carbamoylcyclohexylamino)-5-[(S)-2-{4-(5-iodo-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)-benzamido]-6-[(E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)acrylamido}hexanamido]-6-oxo-hexanoic Acid (7)

Radioiodinating of compound bromobenzimazole carboxamide 5 using Na125I was evaluated by a number of methods and conditions but the following procedure provided the most consistent and best yields. Briefly, 50 μL of a 2.5 mM solution of compound 5 in 1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) were added to 50 μL 5 M solution of chloramine-T in distilled water and mixed in a vial containing 185 MBq of Na125I and 10 mol % of CuI at 50 °C for 20 min. This mixture was then quenched with 100 μL of 5 mM sodium bisulphite for about 15 min. Radiolabeled 7 was eluted through C18 spin column with 250 μL of 1:1 acetonitrile/water. Radiolabeling yields were in range of 20–25%, with specific activities ranging from 25.4 to 38.0 MBq (0.8–1.2 μCi)/μmol (specific activity was calculated and corrected after final purification). Quality assurance of the compound 7 was estimated by reverse-phase HPLC with radioactive and UV detectors and the labeled peptide showed a single peak of >95% purity. The final purified products showed >95% monomeric compounds by C18 TLC, reverse-phase HPLC and CAE runs of 11 and 45 min; the unbound radioiodine was <5%.

[125I]-(S)-6-[1-{(S)-3-Amino-2-(4-hydroxy-3-iodobenzyl)-3-oxopropanoyl-carbamoyl}cyclohexylamino]-5-[(S)-2-{4-(5-bromo-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)benzamido]-6-[(E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)-acrylamido}hexanamido]-6-oxohexanoic Acid (8)

A 2.5 mM solution of compound 5 (200 μg, 50μL) in 1 M sodium phosphate (adjusted to pH 7.0 with H3PO4) was added to 50 μL of a 5 mM solution of chloramine-T in DMSO (200 μL) and mixed in a vial containing Na125I (1 mCi, 10 μL), 10 mol % diethyldiamine and 10 mol % ratio of CuI at 50 °C for 20 min. After 20 min this mixture was quenched with 100 μL of a 5 mM solution of NaHSO3 in H2O for 15 min. Crude radiolabeled 8 was eluted through C-18 spin column with 250 μL of 1:1 acetonitrile/water to afford pure 8 in 90% radiochemical yield, with specific activities ranging from 25.4 to 38.0 MBq (2 μCi)/μg, and >95% purity. The final purified products showed >95% monomeric compounds by C-18 TLC, RP-HPLC and CAE runs of 11 and 45 min; the unbound radioiodine was <5%.

General Procedure for Halobenzimidazole Acids: 4-(5-Fluoro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)benzoic Acid (10)

Our previously reported methods (16) were used with the following exceptions: A sealable microwave tube was used as the reaction vessel and after the consumption of 9 as determined by TLC, 1,3-diisopropylcarbodiimide (451 μL, 2.90 mmol) was added, the tube was sealed, and the reaction mixture was microwave heated to 80 °C for 11 min. After our previously described workup, this crude ester was then dissolved in DMF (8 mL), transferred to a sealable microwave tube, treated with Ba(OH)2 (1.65 g, 9.65 mmol), and microwave heated to 140 °C for 21 min. The previously described filtered to afford 10 (225 mg, 86%) as a gray solid: ESI-MS (m/z) 272 (M+H)+; Purity (HPLC): 98%.

4-(5-Chloro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)benzoic Acid (11)

Following the General Procedure for Halobenzimidazole Acids afforded 11 as a gray solid (249 mg, 89%): ESI-MS (m/z) 288, 290 (M+H)+; Purity (HPLC): 99%.

4-(5-Bromo-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)benzoic Acid (12)

Following the General Procedure for Halobenzimidazole Acids afforded 12 as a gray solid (205 mg, 64%): ESI-MS (m/z) 332, 334 (M+H)+; Found C, 50.70; H, 3.03; N, 12.63. Purity (HPLC): 100%.

4-(5-Iodo-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)benzoic Acid (13)

Following the General Procedure for Halobenzimidazole Acids afforded 13 as a brown solid (275 mg, 75%): ESI-MS (m/z) 380.0 (M+H)+; Purity (HPLC): 97%.

(S)-6-[1-{(S)-3-amino-2-(4-hydroxybenzyl)-3-oxopropanoylcarbamoyl}cyclohexyl-amino]-5-[(S)-2-{4-(5-bromo-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)benzamido]-6-[(E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)acrylamido}-hexanamido]-6-oxohexanoic Acid (17)

Our previously reported methods (22) afforded first 16 and then 17 as a yellow solid (6 mg, 4.9%): ESI-MS 1023.69 (m/z) (M + H)+. Purity (HPLC) 91%.

[125I]-(S)-6-[1-((S)-1-amino-6-(4-iodobenzamido)-1-oxohexan-2-ylcarbamoyl)-cyclohexyl-amino]-5-[(S)-2-(4-(5-bromo-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)benz-amido]-6-[(E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)acrylamido)hexanamido]-6-oxohexanoic acid (18)

Amine 21 (50 μg, 41.2 μmol) and N-succinimidyl-4-[125-I]iodobenzoate (14 μg, 41.2 μmol, 200 μCi; Ref 45) in alkaline water (pH 8.0) was warmed to 60 °C for 1 h. Crude 18 was eluted through C18 spin column with 250 μL of 1:1 acetonitrile/water to afford pure 18 in 47% radiochemical yield, with a specific activity 1.7 μCi/g, and >95% purity. Purity (C18 TLC and RP-HPLC): >90%.

(S)-5-((S)-2-(4-(5-bromo-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-ylamino)benzamido)-6-((E)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)acrylamido)hexanamido)-6-(1-((S)-1,6-diamino-1-oxohexan-2-ylcarbamoyl)cyclohexylamino)-6-oxohexanoic acid (21)

Our previously reported methods (16) afforded 21 (4.9 mg, 4.2%) as a white powder: ESI-MS 988.46 (m/z) (M + H)+. Purity (HPLC): 100%.

Multiple Sequence Alignment and Model Building

The sequence alignment between α4β1 integrin and the template (αIIbβ3 integrin (21), see Supplementary Figures 3–4) was performed using PSI-BLAST-ISS (22). Sequences having similarity to both α4β1 and αIIbβ3 integrins were used as seeds to generate corresponding PSI-BLAST profiles (23) which were extracted and compared. Protein models were generated using MODELLER (24).

Docking simulations

Compounds were docked in the vicinity of Trp188 in (α4) using Autodock (25). The partial atomic charges for the ligands were obtained using the AM1-BCC (26) method and united atom charges were used for the integrin (27). An 80×90×90 grid was used with a spacing of 0.375 Å and centered above Trp188. A Lamarckian algorithm was used to generate ligand conformations using previously reported parameters while keeping the energy evaluations at a maximum of 150,000 (28). A total of 5,000 conformers were generated for each ligand and clustered using a 2.0 Å RMSD.

Cell Adhesion Assay

The cell adhesion assay method is described elsewhere (14, 16).

Animal Biodistribution Study for 7

Eleven female BALB/c nu/nu mice, 5–6 weeks old (UC Davis animal care facility), were xenografted s.c. in the abdomen with 5 × 106 Raji cells. Three weeks after inoculation, the tumor size of the mice was measured. The mice were injected i.v. with 4–6 μCi of 125I-labeled 7 (5 μg, 6 nmol) with normal saline as the vehicle. The mice were sacrificed at 4, 24 and 48 h post injection and tissue samples were excised. The tissue samples were weighed and radioactivity was measured in a γ-counter. Uptake in harvested organs was expressed as % ID/g of tissue.

Animal Biodistribution Study for 18

Six female BALB/c nu/nu mice, 5–6 weeks old (UC Davis animal care facility), were xenografted s.c. in the abdomen with 6 × 106 Raji cells. Three weeks after inoculation, the tumor size of the mice was measured. The mice were injected i.v. with 18 (5 μg, 4 nmol, 12 μCi specific activity) with normal saline as the vehicle. Three mice were sacrificed at 24 h post injection and the other three at 48 h post injection, and tissue samples were excised. The tissue samples were weighed and radioactivity was measured in a γ-scintillation counter. Uptake in harvested organs was expressed as % ID/g of tissue.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

Both the azole carboxamide and bromoazole acetamide series were previously known to be ineffective ligands for α4β1 integrin. Indeed, previous SAR studies found that a methylene unit between the amide and the phenyl ring (i.e., arylacetamide) was believed to be a critical motif for potency (3) while bromo substitution was ineffective at increasing potency (14, 16). Nonetheless, molecular modeling studies revealed a channel near the ligand binding site where a halogen atom could potentially interact (16). Halogenated ligands are all particularly attractive for use in medicine and biology as either a radiodiagnostic (18F), a radiotherapeutic (131I), or a molecular structure tool (Cl or Br). In the latter example, either chloro or bromo ligands could be utilized to provide valuable molecular insight into the integrin structure in either photoaffinity cross-linking/mass spectroscopy experiments (Cl, 3:1 35Cl:37C; Br, 1:1 79Br:81Br), as well as co-crystallization X-ray studies (heavy atom effect). This provided the impetus behind the synthesis of halobenzimidazole analogues 10–13 (Supplementary Scheme 1).

While milder tandem reactions have been recently developed to afford m- and p-azole esters in good yields (29, 30), the reaction conditions shown in Supplementary Scheme 1 quarter the amount of time to deliver halobenzimidazole acids 10–13 through microwave-mediated chemistry (31). Briefly, commercially available aniline esters were treated with thiophosgene to afford the aryl isothiocyanate ester 9 in 83% yield. Following purification by short path column chromatography, this aryl isothiocyanate ester was reacted with 4-halo-o-phenylenediamine to yield an intermediate bisaryl thiourea that, in the presence of 1,3-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), was cyclized to yield crude benzimidazole esters and 1,3-diisopropylthiourea as a by-product. These esters are rapidly saponified to afford halobenzimidazole acids 10–13 (64–89% yield) that are analytically pure following acidification and filtration (32). This streamlined route, coupled with previous reports focusing on milder reagents and conditions that minimize purification (16, 29), significantly improves the preparation of these medicinally-pertinent azole heterocycles which are present in nearly one-quarter of the top 100 drugs (33).

With these halobenzimidazole acids in hand, effort was then directed towards the synthesis of target molecules 3–6 (Supplementary Scheme 2). The tripeptide 14, prepared previously from Rink amide resin (14), was N-acylated with halobenzimidazole acid precursors 10–13, followed by acid-mediated deprotection and resin cleavage to afford crude 3–6. Purification by reverse-phase HPLC and lyophilization delivered pure halobenzimidazole carboxamide analogues 3–6 in 22–46% overall yield from Rink amide resin.

In Vitro Biological Evaluation

Halobenzimidazole carboxamide analogues 3–6 were then subjected to cell adhesion competitive inhibition assays to determine in vitro activity and potency. Lusinskas reported that α4β1 integrin mediates cell adhesion to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1; CD106) and the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin. The 25-mer peptide CS-1 (DELPQLVTLPHPNLHGPEILDVPST), the binding motif of fibronectin to α4β1 integrin, provides a natural ligand to measure the binding affinities (IC50) of the halobenzimidazole carboxamide analogues 3–6.

Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with neutravidin followed by treatment of biotinylated CS-1 to immobilize the natural ligand to the well of the plate. The remaining non-neutravidin bound sites were blocked with BSA and the wells were incubated with Molt-4 cells (human T-cell leukemia; contains α4β1 integrin). The plates were then washed, fixed with formalin, stained with crystal violet, and the absorbance (570 nm) was measured using a UV/Vis spectrophotometer equipped to read 96-well plates. Inhibition was calculated as a percentage resulting from the concentration-dependent curve (see Supplementary Materials), with the potency of 3–6 shown in Figure 2a. While all compounds have an affinity for α4β1 integrin at <5 nM, these data suggest that the type of halogen atom plays a critical role for ultrapotency in this class of halobenzimidazole analogues. The bromo, fluoro, and iodo derivatives are particularly promising; the bromo compound 5 is only 2-fold less potent than previous leads (4, 20), while the fluoro (3) and iodo (6) analogues could potentially be highly potent radiodiagnostic (F-18) and radiotherapeutic (I-131) agents.

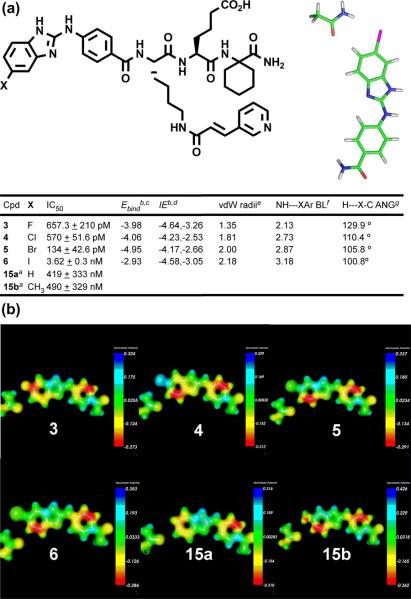

Figure 2.

(a) Potency (IC50), estimated binding energies, calculated interaction energies, and amide-halogen geometries, where the amide represents a nearby primary amide of Asn161 (α4 subunit) side chain: a. see Ref. 14 for more on 15a, Ref. 16 for more on 15b; b. Energies are expressed in units of kcal/mol; c. estimated binding energies (Ebind), where Ebind = RT*ln[IC50(X = halogen)/IC50(X = H)]; d. Calculated interaction energy for amide-halogen interaction (gas-phase) using MP2/6-311++G(d,p)//B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory, second values are the BSSE corrected energies; e. Distances for the van der Waal's (vdW) radii of each halogen are expressed in Å; f. Distances (in Å) represent the C(O)NRH---XAr H-bond length; g. Represents the H-X-Ar angle in the C(O)NRH---XAr H-bond. (b) Electrostatic potential maps for 3–6 and 15a–b.

SAR and Theoretical Calculations

Interestingly, the SAR for this class of benzimidazole carboxamides (see Figure 2a) revealed that both the unsubstituted benzimidazole (15a; Ref. 14) and 56-methylbenzimidazole (15b; Ref. 16) were 1000-fold less potent than fluoro, chloro, and bromo analogues 3–5 as well as 100-fold less potent than iodo analogue 6. These data suggest that hydrophobic interactions were not responsible for ultrapotency, as both 15a and 15b were equipotent. Additionally, steric interactions were also not responsible, as 1000-fold difference was seen between isosteres 15a and 3 as well as 15b and 4. Electrostatic interactions were also examined; however these interactions were not important as the electrostatic potential of 3–6 and 15a–b (see Figure 2b) did not correlate with the observed potency. Therefore, attention turned towards aryl halide-derived interactions which have occurred in prior systems through aryl halide-H-bonding (34) or halogen- carbonyl dipole-dipole interactions (35, 36).

To further understand if aryl halide-H-bond and/or dipole-dipole interactions were involved, the binding energy (Ebind) was estimated for 3–6 (see Figure 2a) using the equation Ebind = RT*ln[IC50(X = halogen)/IC50(X = H)], where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature at 25 °C. Quantum mechanical calculations were performed where halobenzimidazoles interacted with primary amide (i.e., Asn/Gln), ammonium (Lys), or carboxylate (Asp/Glu) side chains. Interestingly, only calculations involving the interaction between the primary amide side chain of Asn or Gln with halobenzimidazoles gave results consistent with the experimental observations, thereby eliminating Lys, Asp, and Glu residues as well as charge-transfer interactions. These data suggest that the nature of either the H-bond donor or carbonyl source is critical for ultrapotency.

The nature of the amide-aryl halide interaction was elucidated by investigating the geometries and interaction energies of both the carbonyl oxygen and the amide N-H interacting with the halobenzimidazole. Having the hydrogen N-H interacting with the halogen gave a stabilizing interaction for halobenzamidazoles 3–6. While the carbonyl oxygen interacting with heavier halo analogues 4–6 was stabilizing, it was unfavorable when interacting with fluoro analogue 3. The gas-phase calculated interaction energies (IE) were then determined at the MP2/6-311++G(d,p)//B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level and ranged from 3.5 to 4.0 kcal/mol as shown in the chart of Figure 2a. These IE values were primarily due to the H-bond between the primary amide of Asn161 (α4 subunit) and the halobenzimidazole moiety. The IE values predict the fluoro analogue 3 would be the most potent, however all IE values are very close (within 0.5 kcal/mol) and are comparable to experimentally observed Ebind values. The variation in potency is likely explained by bromo analogue 5 having the halogen with the requisite van der Waal's atomic radii (2.00 Å for Br; Ref. 37) and positioning of the halogen atom (105.8 °; angle of the C(O)NRH⋯X-Ar H-bond, where X is the central atom of the angle and a halogen, is taken from the minimized energy structures shown generically in Figure 2a) allowing for this key amide-halogen H-bond (bond length between H⋯X = 2.87 Å) while permitting other moieties to interact with the α4 and β1 subunits (such as the butanoate-Mg2+ interaction at the MIDAS site of the β1 subunit; Ref. 16). This theory helps explain why the larger iodo analogue 6 (the poorest H-bond acceptor) is approximately 10-fold less potent than the fluoro (3), chloro (4), and bromo (5) analogues and 100-fold more potent than the unsubstituted (15a) and methyl analogues (15b).

Radioiodination via Aromatic Finkelstein and Initial Biodistribution Studies

The condensed radioiodide derivatives 7 and 8 were attractive targets to potentially serve as therapeutic or diagnostic agents for T- and B-cell lymphomas. Radioiodo derivative 7 was particularly attractive, as this could be synthesized from the bromo analogue 5 in a copper-mediated radioiodination (38, 39). Buchwald's copper(I)-mediated aromatic Finkelstein reaction with cold sodium iodide (i.e., ArBr→ArI) that proceed with average yields of 97% for many aryl and heteroaryl systems seemed a highly promising route to deliver the I-125 enriched 7 from the aryl bromide 5 (Supplementary Scheme 3; Ref. 40). In our hands, this method for radiohalogenation was unsuccessful, presumably due to the structural sophistication of 5 with several potential heteroatoms available for copper chelation. However, treatment of 5 with [125I]NaI/chloramine-T successfully delivered 7 with a radiochemical yield of 20% and a specific activity of 1.0 μCi/μg (125I T1/2 = ~60 d).

Concurrently, Raji cells (human B-cell lymphoma) which abundantly express α4β1 integrin (17), were cultured, centrifuged, and injected into eleven female BALB/c nude mice. These xenograft tumors were allowed to grow to 50–200 mm. The I-125 analogue 7 was then tail vein injected, with animals sacrificed and organs and tumors removed, weighed and counted after 24 and 48 h. Although only one dose formulation was given and dose injections were performed at the same time in an identical manner for all mice, the blood clearance and biodistribution data allowed us to separate the mice into two groups: one with slow blood clearance and one with fast blood clearance (Supplementary Fig. S1 and S2). Three mice showed slow clearances (2 mice at 24 h and 1 mouse at 48 h). These mice had approximately 15% still circulating in the blood thus providing high tumor uptakes of greater than 6% ID/g. The liver, spleen and marrow uptakes were less than 8% ID/g at 48 h. However, five mice (3 mice at 24 h and 2 mice at 48 h) showed that 7 was cleared rapidly from the blood and body. The major dose (25% ID/g) was mainly accumulated in liver, spleen and marrow, while the tumor uptake of these mice was very low (less than 1.5% ID/g).

While these preliminary data have low statistical significance, we believe these results warrant further discussion and may be due to one or more factors. The radioiodo analogue 7, having reduced in vitro affinity for α4β1 integrin by nearly ten-fold compared to the bromo analogue 5, may have decreased in vivo affinity and selectivity. The iodobenzamidyl moiety of 7 may also be metabolically degraded, as seen with p-radioiodobenzamide derivatives (41, 42). While we did not see in vitro peptide aggregation of 7, it has been reported that the fast clearance patterns may be due to in vivo aggregation resulting in ineffective tumor targeting (43).

Radioiodination via Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution

In addition to these mixed in vivo results (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2), 7 was difficult to prepare in high radiochemical yield and crude purity. This provided impetus for the synthesis of 3-radioiodotyrosine-derivative 8, as tyrosine residues are rapidly radioiodinated with high regio- and chemoselectively (44, 45). Moreover, previous optical conjugates 1-Cy5.5 and 2-Cy5.5 showed that the primary amide is successfully modified to a secondary amide without affecting activity, potency, or selectivity (3, 13, 15–17). With this in mind, Rink amide resin was first swollen in DMF for 3 h, followed by Fmoc-deprotection and N-acylation with semi-orthogonally protected tyrosine to deliver the tyrosylated resin 16 (Supplementary Scheme 2). This resin was further elaborated into the bromobenzimidazole tetrapeptide 17 through analogous chemistry (Supplementary Scheme 2) and further elaborated elsewhere (20). This tyrosine derivative 17 was then rapidly radioiodinated using I-125 enriched sodium iodide with iodogen as an oxidant to afford the 3-radioiodo tyrosine derivative 8 in 90% radiochemical yield and with a specific activity of 2 μCi/μg. Unfortunately, 8 performed poorly in in vitro binding studies (<4%) and thus in vivo studies were not pursued. However, these in vitro results should not necessarily be viewed detrimentally; the o-hydroxyl group has been known to weaken the carbon-iodine bond and radioiodotyrosine derivatives have been known to undergo in vivo degradation due to their structural similarities to thyroid hormones (46).

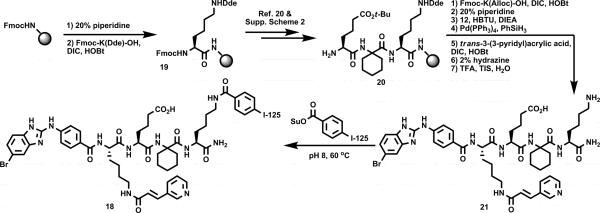

Radioiodination via Succinimidyl Ester Chemistry and Biodistribution Studies

Attention was then turned towards the synthesis of 4-radioiodobenzamidolysine-derivative 18, as the bulkiness of the iodotyrosine may contribute to the poor in vitro binding. Rink amide resin was first swollen in DMF for 3 h, followed by Fmoc-deprotection and N-acylation with Fmoc-Lys(Dde)-OH to deliver resin 19 (Figure 3). Resin 19 was further elaborated into resin 20 through analogous chemistry (Supplementary Scheme 2) and described elsewhere (16). N-acylation of 20 with Fmoc-Lys(Alloc)-OH was followed by Fmoc-deprotection, and then coupling with bromobenzimazole acid 5. Alloc deprotection, followed by N-acylation with trans-3-(3-pyridyl)acrylic acid, Dde deprotection, and TFA cleavage yielded 21. The lysinated bromobenzimadole 21 was radioiodinated by coupling the free amine of the lysine with the NHS-ester of I-125 enriched 4-iodobenzoic acid (prepared from p-aminobenzoic acid as outlined by Khalaj et al.; Ref. 45) to afford the 4-radioiodobenzamidolysine derivative 18 in 47% radiochemical yield and with a specific activity of 1.7 μCi/μg.

Figure 3.

Preparation of 18 from the tyrosine derivative 19.

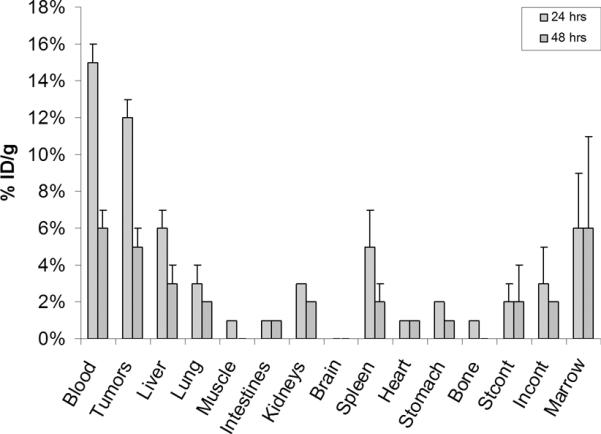

To study the preliminary biodistribution of 18, Raji cells (human B-cell lymphoma) expressing α4β1 integrin were cultured, centrifuged, and injected into six nude mice. These xenograft tumors were grown to 50–200 mm. The I-125 analogue 18 was then tail vein injected, with half of the animals being sacrificed after 24 h and 48 h. As shown in Figure 4, the organs and tumors were removed and counted with 18 having good tumor uptake (12 ± 1% ID/g at 24 h and 4.5 ± 1% ID/g at 48 h) and minimal uptake in other organs. In particular, the low kidney uptake (tumor:kidney(t = 24h) ~4:1; tumor:kidney(t = 48h) ~2.5:1) was encouraging as this, in this initial assessment, has demonstrated that radio-labeled azole anologue 18 may be a promising payload-ligand conjugate for targeting activated α4β1 integrin expressed tumors.

Figure 4.

Ex vivo radio-uptake data of 18 for various tumors and organs.

Conclusion

The results presented have demonstrated the importance of advancing leads to target cancerous but not normal cells by exploiting the conformational differences of α4β1 integrin. The synthesis of azole heterocycles, which previously required harsh reaction conditions, long reaction times, and highly toxic reagents, can now be rapidly prepared through microwave-mediated synthesis using safer reagents with minimal purification. This report also provides an excellent example of how molecular models can be used as a guide to predict analogues that will have high affinity and to understand key weak-force interactions. The potency of this unique class of compounds is likely attributed to a key aryl halide-hydrogen bond between the halobenzimidazole moiety and the primary amide side chain of Asn161 in the α4 subunit. In preliminary studies, the condensed radio-iodobenzimidazole analogue 18 demonstrates that a low tumor:kidney ratio may be achievable with a covalently attached radio-labeled modality while minimizing the size and cost of the payload-ligand conjugate. These halobenzimidazoles are particularly attractive as this allows for the design of highly condensed ligand-payload conjugates for radiotherapeutic (I-131) and radiodiagnostic (F-18) agents for selectively detecting and treating T- and B-cell lymphomas that express α4β1 integrin. Additionally, the bromo analogues 5 could provide valuable molecular insight into the binding site and integrin structure through photoaffinity cross-linking/mass spectroscopy (1:1 79Br:81Br) as well as co-crystallization X-ray studies (heavy atom effect).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Cancer Institute (U19CA113298), National Science Foundation (CHE-0614756), National Institute for General Medical Sciences (RO1-GM076151), American Chemical Society's Division of Medicinal Chemistry Predoctoral Fellowship sponsored by Sanofi-Aventis (R.D. Carpenter), Howard Hughes Medical Institute Med into Grad Fellowship (R.D. Carpenter), UC Davis R. B. Miller Graduate Fellowship and Outstanding Dissertation Award (R.D. Carpenter), Alfred P. Sloan Minority Ph.D. Program (D.M. Solano), and UC Davis Alliance for Graduate Education and the Professoriate Advantage Program (D.M. Solano). NMR spectrometers were in part funded by the National Science Foundation (CHE-0443516 and CHE-9808183). A portion of this work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344.

Footnotes

This research is dedicated in remembrance of our former colleague Professor Aaron D. Mills (University of Idaho).

Assistance with data compilation by Gary Mirick (UC Davis Cancer Center) is duly acknowledged.

Supplemental Data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

K.S. Lam and M.J. Kurth share senior authorship.

Supplemental Data for this research article is available at Cancer Research Online.

References

- 1.Hait WN. Targeted cancer therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1263–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimaoka M, Takagi J, Springer TA. Conformational regulation of integrin structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:485–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.101101.140922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng L, Liu R, Marik J, Wang X, Takada Y, Lam KS. Combinatorial chemistry identifies high-affinity peptidomimetics against α4β1 integrin for in vivo tumor imaging. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:381–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin KH, Slack JK, Boerner SA, Martin CC, Parsons T. Integrin connections map: To infinity and beyond. Science. 2002;296:1652–3. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusuf-Makagiansar H, Anderson ME, Yakovleva TV, Murray JS, Siahaan TJ. Inhibition of LFA-1/ICAM-1 and VLA-4/VCAM-1 as a therapeutic approach to inflammation and autoimmune diseases. Med Res Rev. 2002;22:146–67. doi: 10.1002/med.10001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent AM, Cawley JC, Burthem J. Integrin function in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1996;87:4780–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marco RA, Diaz-Montero CM, Wygant JN, Kleinerman ES, McIntyre BW. α4 integrin increases anoikas of human osteosarcoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:1038–47. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsunaga T, Takemoto N, Sato T, et al. Interaction between leuekmic-cell VLA-4 and stromal fibronectin is a decisive factor for minimal residual disease of acute myelogenous leukemia. Nat Med. 2003;9:1158–65. doi: 10.1038/nm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson DL, Burkly LC, Leone DR, Dolinsky BM, Lobb RR. Anti-α4 integrin monoclonal antibody inhibits multiple myeloma growth in a murine model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:91–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garmy-Susini B, Jin H, Zhu Y, Hwang R, Varner J. Integrin α4β1-VCAM-1-mediated adhesion between endothelial and mural cells is required for blood vessel maturation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1542–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI23445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin H, Su J, Garmy-Susini B, Kleeman J, Varner J. Integrin α4β1 promotes monocyte trafficking and angiogenesis in tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2146–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Fuente MT, Casanova B, Garcia-Gila M, Silva A, Garcia-Pedro A. Fibronectin interaction with α4β1 integrin prevents apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Correlation with Bcl-2 and Bax. Leukemia. 1999;13:266–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park SI, Manat R, Vikstrom B, et al. The use of one-bead one-compound combinatorial library method to identify peptide ligands for α4β1 integrin receptor in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Lett Pept Sci. 2002;8:171–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carpenter RD, Andrei M, Lau EY, et al. Highly potent, water soluble benzimidazole antagonist for activated α4β1 integrin. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5863–7. doi: 10.1021/jm070790o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng L, Liu R, Andrei M, Xiao W, Lam KS. In vivo optical imaging of human lymphoma xenograft using a library-derived peptidomimetc against α4β1 integrin. Mol Canc Ther. 2008;7:432–7. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter RD, Andrei M, Lau EY, et al. Selectively targeting T- and B-cell lymphomas: A benzothiazole antagonist for α4β1 integrin. J Med Chem. 2009;52:14–9. doi: 10.1021/jm800313f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeNardo SJ, Liu R, Albrect H, et al. 111In-LLP2A-DOTA polyethylene glycol-targeting α4β1 integrin: Comparative pharmacokinetics for imaging and therapy of lymphoid malignancies. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:625–34. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.For a recent review, see: Aina OH, Liu R, Sutcliffe JL, Marik J, Pan C-X, Lam KS. From combinatorial chemistry to cancer-targeting peptides. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2007;4:631–51. doi: 10.1021/mp700073y..

- 19.Perkins JJ, Zartman AE, Meissner RS. Synthesis of 2-(alkylamino)benzimidazoles. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:1103–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katritzky AR, Witek RM, Rodriguez-Garcia V, et al. Benzotriazole-assisted thioacylation. J Org Chem. 2005;70:7866–81. doi: 10.1021/jo050670t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao T, Takagi J, Coller BS, Wang JH, Springer TA. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding of fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 2004;432:59. doi: 10.1038/nature02976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margelevicius M, Venclovas C. PSI-BLAST-ISS: an intermediate sequence search tool for estimation of the position-specific alignment reliability. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, et al. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackalian A, Jack DB, Bayly CI. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II. Parameterization and validation. J Comput Chem. 2002;23:1623. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiner SJ, Kollman PA, Case DA, et al. A new force field for molecular simulation of nucleic acids and proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:765. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Legge GB, Morris GM, Sanner MF, Takada Y, Olson AJ, Grynszpan F. Model of the alpha L beta 2 integrin I-domain/ICAM-1 DI interface suggest that subtle changes in loop orientation determine ligand specificity. Proteins: Struc Func Genetics. 2002;48:151. doi: 10.1002/prot.10134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter RD, DeBerdt PB, Lam KS, Kurth MJ. A carbodiimide-based library method. J Comb Chem. 2006;8:907–14. doi: 10.1021/cc060106b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esters in the o-position cyclized to the tetracyclic benzimidazoquinazolinone. For more information and an optimized route to this heterocycle, see: Carpenter RD, Lam KS, Kurth MJ. Microwave-mediated heterocyclization to benzimidazo[2,1-b]quinazolin-12(5H)-ones. J Org Chem. 2007;72:284–7. doi: 10.1021/jo0618066..

- 31.For representative work from this laboratory, see: Carpenter RD, Fettinger JC, Lam KS, Kurth MJ. Asymmetric catalysis: Polystyrene-bound hydroxyprolylthreonine in the enamine-mediated preparation of chromanones. Angew Chem. 2008;120:6507–10. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801811. Angew Chem Int Ed 2008;47:6407-10..

- 32.These unique heating conditions were obtained from Biotage's microwave conversion chart. http://www.biotage.com/DynPage.aspx?id=21996.

- 33.Martin EJ, Critchlow RE. Beyond mere diversity: Tailoring combinatorial libraries for drug discovery. J Comb Chem. 1999;1:32–45. doi: 10.1021/cc9800024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Y, Wang, Yong W, Xu Z, et al. C-X⋯H contacts in biomolecular systems: How they contribute to protein-ligand binding affinity. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:12615–21. doi: 10.1021/jp906352e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auffinger P, Hays FA, Westhof E, Ho PS. Halogen bonds in biological molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16789–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407607101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.For recent aryl iodide interactions with nucleic acids, see: Tawarada R, Seio K, Sekine M. Synthesis and properties of oligonucleotides with iodo-substituted aromatic aglycons: Investigation of possible halogen bonding base pairs. J Org Chem. 2008;73:383–90. doi: 10.1021/jo701634t..

- 37.Peet JH. How big is an atom? Phys Educ. 1975:508–510. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiyono Y, Kanegawa N, Kawashima H, Kitamura Y, Iida Y, Saji H. Evaluation of radioiodinated (R)-N-methyl-3-(2-iodophenoxy)-3-phenylpropanamine as a ligand for brain norepinephrine transporter imaging. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:147–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Araujo EB, Santos JS, Colturato MT, Muramoto E, Silva CPG. Optimization of a convenient route to produce N-succinimidyl 4-radiodobenzoate for radioiodination of proteins. Appl Radiat Isot. 2003;58:667–73. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(03)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klapers A, Buchwald SL. Copper-catalyzed halogen exchange in aryl halides: An aromatic Finkelstein reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14844–45. doi: 10.1021/ja028865v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garg PK, Slade SK, Harrison CL, Zalutsky MR. Labeling proteins using aryl iodide acylation agents: Influence of meta vs para substitution on in vivo stability. Nucl Med Biol. 1989;16:669–73. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(89)90136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilbur DS, Hamlin DK, Chyan M-K, Kegley BB, Quinn J, Vessella RJ. Biotin reagents in antibody pretargeting. 6. Synthesis and in vivo evaluation of astatinated and radioiodinated aryl- and nido-carboranyl-biotin derivatives. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:601–16. doi: 10.1021/bc034229q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshimoto M, Ogawa K, Washiyama K, et al. αvβ3 Integrin-targeting radionuclide therapy and imaging with monomeric RGD peptide. Intl J Cancer. 2008;123:709–15. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandes C, Oliveira C, Gano L, Bourkoula A, Pirmettis I, Santos I. Radioiodination of new EGFR inhibitors as potential SPECT agents for molecular imaging of breast cancer. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:3974–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kersemans V, Cornelissen B, Kersemans K, et al. Comparative biodistribution study of the new tumor tracer [123I]-2-iodo-L-phenylalanine with [123I]-2-iodo-L-tyrosine. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smallridge RC, Burman KD, Ward KE, et al. 3',5'-Diiodothyronine to 3'-monoiodothyronine conversion in the fed and fasted rat: Enzyme characteristics and evidence for two distinct 5'-deiodinases. Endocrinology. 1981;108:2336–45. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-6-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.This was prepared in 4-steps from p-aminobenzoic acid using the following protocol: Khalaj A, Beiki D, Rafiee H, Najafi R. A new and simple synthesis of N-succinimidyl-4-[127/125I]iodobenzoate involving a microwave-accelerated iodination step. J Labelled Cpd Radiopharm. 2001;44:235–40..

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.