Abstract

Background

Quantification of islet mass is a crucial criterion for defining the quality of the islet product ensuring a potent islet transplant when used as a therapeutic intervention for select patients with type I diabetes.

Methods

This multi-center study involved all 8 member institutions of the National Institutes of Health-supported Islet Cell Resources (ICR) consortium. The study was designed to validate the standard counting procedure for quantifying isolated, dithizone-stained human islets as a reliable methodology by ascertaining the accuracy, repeatability (intra-observer variability), and intermediate precision (inter-observer variability). The secondary aim of the study was to evaluate a new software-assisted digital image analysis method as a supplement for islet quantification.

Results

The study demonstrated the accuracy, repeatability and intermediate precision of the standard counting procedure for isolated human islets. This study also demonstrated that software-assisted digital image analysis as a supplemental method for islet quantification was more accurate and consistent than the standard manual counting method.

Conclusions

Standard counting procedures for enumerating isolated stained human islets is a valid methodology, but computer-assisted digital image analysis assessment of islet mass has the added benefit of providing a permanent record of the isolated islet product being evaluated that improves quality assurance operations of current good manufacturing practice (cGMP).

Keywords: Islets of Langerhans, Quality Control, Image Analysis

Introduction

Islet transplantation is a clinical investigational procedure for treatment of select patients with type 1 diabetes (1). In the United States, transplantable allogeneic islets meet the definition of a “drug” in the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), 21 USC 321 (g). The implications are that the process for isolating and purifying islets for clinical transplantation are subject to manufacturing regulations to ensure that a safe, quality product is used for transplantation. A fundamental prerequisite for demonstrating effective and safe manufacturing is the implementation of validated release criteria for the islet product to be infused. In this regard, quantification of the islet mass is the most crucial parameter for defining the dose and potency of the transplanted product (2).

The methodology for quantifying isolated islets has been in evolution for years. In 1980, Downing et al., first established a method for quantifying the irregular sizes of islets from large mammals (3). In general, a small sample of the final islet preparation is stained with dithizone, providing a rapid means for discrimination of islet from acinar tissue, with the positive reaction indicating that insulin containing β cells are present. Using a light microscope with an ocular micrometer, the size distribution of the islets is quantified within a range of 50 to > 400μm by dividing all islets into classes of 50μm increments. Islet volume is calculated, based on the assumption that islets are spherical, and the number of islets is expressed in terms of islet equivalents (IEQs). One IEQ is equal to an islet of 150 μm diameter according to the criterion set at the Second Congress of the International Pancreas and Islet Transplantation Association that established the IEQ as the standard unit of human islet volume (4).

This method for quantification of islet mass meets the specifications of an Identification Test and an Active Ingredient Assay of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines (5). The only analytical performance characteristic relevant to an Identification Test according to ICH guideline Q2(R1) is assay specificity, as previously reported (6, 7). The analytical performance characteristics relevant to an Active Ingredient Assay according to ICH guideline Q2(R1) are specificity, accuracy, repeatability, intermediate precision, linearity and range. Specificity has been addressed already, and linearity and range are not relevant analytical performance characteristics to the final product release uses of this test method, as there is no standard curve from which interpolations are made. Thus, accuracy, repeatability and intermediate precision need to be demonstrated. However, a rigorous analysis of these characteristics has not been reported in the literature.

Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to validate the standard counting procedure of dithizone-stained islets as a suitable release criterion for quantifying the islet mass by ascertaining the accuracy, repeatability (intra-observer variability), and intermediate precision (inter-observer variability) of this method in a multi-center study. The secondary aim of this study was to evaluate a new software-assisted digital image analysis system at one experienced center as a potential supplementary method for islet quantification. Based on previous reports in the oncology pathology field, software-assisted image analyses were demonstrated to be superior to conventional manual light-microscopic measurement for tissue quantification (8–10), and is the current methodological standard. We hypothesized that computer-assisted image analysis would give more accurate and reproducible results than the established manual counting procedure for quantification of isolated islets. Image analysis could therefore benefit the quality assurance process of current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) of the islet isolation process by providing a permanent and verifiable record of the islet product being evaluated.

Materials and Methods

Manual Counting

All 8 member institutions of the Islet Cell Resource (ICR) Consortium, including 36 technicians, participated in this study. The study design was performed by the Administrative and Bioinformatics Coordinating Center (ABCC) of the ICR to evaluate consistency and accuracy of the IEQ counting results for this consortium. Twenty-six micrographs of human islets that were originally used in the 2001 Immune Tolerance Network (ITN) International Clinical Islet Transplant Study were provided to the ABCC by the Emmes Corporation. The ABCC incorporated the photographs into a Counting Manual and distributed it to all centers following an ABCC sponsored workshop where instructions were given as to how to proceed with the counting project and details for use of the manual. It contained a detailed protocol, a practice set of two photographs depicting numbered islets with a tabulation key to check the estimated answers, and two sets (A & B) of twelve photographs each of dithizone-stained human islets. Each set of photographs mimicked a purified human islet preparation as seen through a 4x ocular and a 4x objective in a inverted microscope. Each photograph represented the individual scans needed to view an entire preparation. A transparent grid, calibrated so that the edge length of each small square represented 50 μm on the islet images assisted in sizing the islets, substituting an eyepiece reticle. The islets were to be graded for each picture in the previously established size categories (4) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Established size categories in which islets were scored to determine the total islet equivalent for an islet preparation.

| Diameter range for a circular islet | Equivalent Minimum 50 μm Grid Squares | Equivalent Maximum 50 μm Grid Squares | Multiplier for IE volume conversion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50–100 μm | 0.8 | 3.1 | 0.167 |

| 101–150 μm | 3.2 | 7.1 | 0.667 |

| 151–200 μm | 7.2 | 12.6 | 1.685 |

| 201–250 μm | 12.7 | 19.6 | 3.500 |

| 251–300 μm | 19.8 | 28.3 | 6.315 |

| 301–350 μm | 28.5 | 38.5 | 10.352 |

| 351–400 μm | 38.7 | 50.3 | 15.833 |

| >400 μm | 50.5 | --- | 22.750 |

This study required that all technicians at each of the ICR institutions that were experienced with quantifying islets during islet isolations, to complete a common training program for islet quantification. Participants worked through a practice set to validate their counting results with those of an Expert Panel who established the “gold standard” islet quantity for each set of photographs. The Expert Panel was made up of three investigators who collectively had over forty years of human islet counting experience, including one that helped establish the IEQ counting method in 1987. These three experts used the Delphi approach (11) to review their individual counts and develop a consensus for the best values which then became the gold standard results.

Once the investigators at the ICR institutions completed training, they proceeded to count the photographed islet preparations in Sets A and B for analyses by the ABCC. At a later date the participants repeated the islet quantification using the same photograph set to establish repeatability of the standard manual counting method.

All data were collected by the ABCC, entered into a database, and statistically analyzed.

Digital Image Analysis

The same two sets of twelve photographs that were manually analyzed by all ICR institutions were also subjected to a software-assisted digital image analysis methodology being developed at one center. The photographs and the scored transparent grid were scanned with a flatbed scanner and stored as TIF files, which were used for image analysis using the software program, Image Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). All islet images were spatially calibrated using the pixel conversion into μm derived from the scored transparent grid image. The calibrated images were then evaluated by three operators, who were well experienced in islet counting and image analysis. The image analysis procedure required the following process: after opening the calibrated images in the software image window, islets were identified by color segmentation that allowed the operator to interactively separate the objects from the background based on color characteristics, i.e. red for dithizone-stained islets. Islets were classified into discrete areas by boundaries of the individual particles. The individual islet areas were automatically measured and exported to an excel spreadsheet. A customized spreadsheet was used to characterize each islet sample on the images using the standard characteristics of total islet number, islet number per size class, and IEQ. Adhering to the convention that islets are spherical particles (4), the radius was derived from the area with the formula radius = √(area/π), assuming the area represents a circle, and used to classify islets into size groups, as per Table 1.

Statistical Methods

Thirty-six technicians from the 8 ICR institutions participated in the manual counting exercises. In reporting their results, each ICR Isolation Center was de-identified using an alphabetical symbol (A–H) representing each center, and each technician that reported the islet mass was represented by an alphanumeric symbol (e.g. A1 for the first technician within Center A). Of the 36 technicians, 35 participated in the reproducibility assessment. In addition, three technicians from one of the ICR institutions also applied the software-assisted digital imaging methodology to enumerate all islets in each set. They also participated in the reproducibility assessment to measure intra-observer variability. Three analyses were performed for each institution that performed the manual counts to evaluate the performance: 1.) accuracy (compared to Expert Panel standard), 2.) repeatability (intra-technician variability), and 3.) intermediate precision (inter-technician variability).

Accuracy was assessed by calculating one sample t-tests to compare the mean total IEQs of each center to the Expert Panel standard. This test determines if a center has a bias of either over or under estimation of IEQ counts. Both the manual counts and the software-assisted imaging analyses results were compared to the Expert Standard that was previously defined.

To assess intra-technician variability, coefficients of variation (CVs) were calculated for the two repeat counts for each picture. This was done for all technicians that repeated the counting exercise either manually, or with the imaging software. To determine inter-technician variability within centers, CVs were calculated for manual counting results across all technicians within each center, and for the software assisted image analysis results in all first readings across technicians. For Picture Sets A and B, the mean total IEQs was used in calculating the CVs. CVs were calculated two ways: 1.) by comparing each technician’s total IEQs over all 12 pictures by Picture Set (CV Across Techs) and 2.) by calculating a CV across technicians for each of the 12 pictures and then averaging the 12 CVs to get an average CV for each center by Picture Set (Average CV). Intra-technician and inter-technician variability were determined using the coefficient of variation due to its descriptive nature and ease of interpretation.

Results

Accuracy

Center accuracy to compare each center’s counts with the expert standard is given in Table 2. In picture set A, the expert standard mean total islet equivalent (IEq) was 399.6. One sample t-tests against the expert standard showed that Centers A, E, and H produced counts that were statistically significantly different from the standard (p = 0.03, 0.004, 0.01, respectively). In picture set B, the expert standard mean total IEq was 112.6. Centers C, E, and H produced counts that were statistically significantly different from the expert standard for picture set B (p = 0.04, .002, 0.05, respectively). The magnitude of bias for centers’ average counts were over 10% of the expert standard in 2 centers for picture set A and 4 centers for picture set B.

Table 2.

Accuracy of Center and Imagining Software Count of Total IEQ’s from Expert

| Picture Set | Center | No. of Techs | Mean Total IEQs ± Std Dev | P-value for Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Standard | 399.6 | |||

|

| ||||

| A | A | 6 | 449 ± 40 | 0.03 |

| B | 2 | 365 ± 12 | 0.16 | |

| C | 4 | 389 ± 21 | 0.39 | |

| D* | 2 | 376 ± 4 | 0.07 | |

| E | 6 | 425 ± 13 | 0.004 | |

| F | 3 | 414 ± 23 | 0.38 | |

| G | 8 | 390 ± 50 | 0.60 | |

| H | 5 | 507 ± 53 | 0.01 | |

|

| ||||

| Imaging Software | 3 | 395 ± 9 | 0.45 | |

|

| ||||

| Expert Standard | 112.6 | |||

|

| ||||

| B | A | 6 | 128 ± 23 | 0.16 |

| B | 2 | 117 ± 10 | 0.65 | |

| C | 4 | 127 ± 8 | 0.04 | |

| D* | 2 | 121 ± 3 | 0.15 | |

| E | 6 | 131 ± 8 | 0.002 | |

| F | 3 | 120 ± 3 | 0.06 | |

| G | 8 | 113 ± 29 | 0.98 | |

| H | 5 | 149 ± 28 | 0.05 | |

|

| ||||

| Imaging Software | 3 | 120 ± 2 | 0.02 | |

Center D only had one technician recount the data, however the other technician was kept in this analysis and further analyses in order to calculate descriptive statistics and run analytical tests where only the first count for each technician is used.

Using the image analysis software, islet counts for Picture Set A were not statistically different from the expert standard, but counts for Picture Set B were significantly different from the expert standard (p = 0.45 and 0.02, respectively). However, the magnitudes of bias for software-assisted average counts were within 10% of the expert standard for both picture sets. The bias was also smaller than that of manual counts produced by all 8 and 7 of 8 centers for picture sets A and B, respectively.

Intra-technician variability

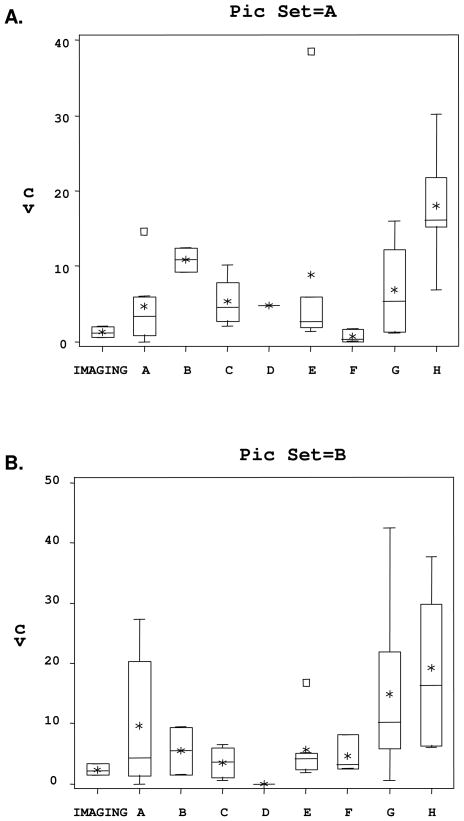

Repeatability of results was assessed for the 35 technicians that performed a second count, with boxplots showing the CVs for each technician by center and picture set (Figure 1). For Picture Set A, the intra-technician CVs ranged from 0.0 to 38.5. The majority of technicians (57%) were within a CV of 6, and 29% had a CV over 10. The average CV for Picture Set A for all manual counters was 7.9. For Picture Set B, the CVs ranged from 0.0 to a maximum of 42.5. In this picture set 51% of technicians were within a CV of 6, and 29% had a CV over 10. The average CV for all manual counters was 9.9.

Figure 1.

Intra-Technician Variability. Coefficient of Variation between 1st and 2nd IEQ Count for Each Technician by Picture Set A and B According to Center.

The 3 technicians using the software-assisted imaging analysis method achieved CVs of 0.6, 2.0, and 1.2, respectively, for Picture Set A, and CVs of 1.5, 3.4, and 2.1, respectively, for Picture Set B. These data indicate the ratio of intra-technician CVs between software-assisted readings and manual counts was only 16% (1.3 vs. 7.9) and 24% (2.3 vs. 9.9) for picture sets A and B, respectively.

Inter-technician Variability

Intermediate precision (inter-technician variability), was assessed via the CVs of mean total IEQs for manual counting results within each center, and for the software-assisted imaging analysis results (Table 3). For the manual counting procedures, the CVs for Picture Set A ranged from 1.0 to 12.9. The average CV across pictures within Set A ranged from 10.8 to 21.2. Overall the total number of IEQs enumerated ranged from 315 to 595, with a CV of 12.9. The expert standard mean total islet IEq was 399.6.

Table 3.

Inter-technician Variability. Coefficient of Variation (CV) for Total IEQs across Technicians within Each Center by Picture Set

| Picture Set | Center | No. of Techs | Mean Total IEQs | Range of Mean Total IEQ’s | CV Across Techs | Average CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | A | 6 | 448.5 | 414.5 – 523.8 | 9.0 | 17.1 |

| B | 2 | 365.1 | 356.3 – 373.9 | 3.4 | 11.3 | |

| C | 4 | 389.3 | 371.0 – 413.7 | 5.3 | 11.4 | |

| D | 2 | 375.6 | 372.9 – 378.2 | 1.0 | 15.8 | |

| E | 6 | 425.4 | 400.9 – 435.3 | 3.0 | 10.8 | |

| F | 3 | 414.1 | 393.4 – 438.3 | 5.5 | 19.1 | |

| G | 8 | 390.0 | 315.2 – 474.4 | 12.9 | 19.0 | |

| H | 5 | 506.6 | 463.8 – 594.8 | 10.6 | 21.2 | |

| All Manual Counters | 36 | 421.6 | 315.2 – 594.8 | 12.9 | 20.3 | |

| Imaging Software | 3 | 394.6 | 384.6 – 402.6 | 2.3 | 8.1 | |

| Expert Standard | 399.6 | |||||

| B | A | 6 | 128.1 | 114.9 – 174.3 | 17.9 | 19.8 |

| B | 2 | 117.1 | 109.8 – 124.4 | 8.8 | 18.2 | |

| C | 4 | 126.6 | 120.7 – 138.4 | 6.4 | 13.6 | |

| D | 2 | 120.7 | 118.8 – 122.7 | 2.3 | 16.5 | |

| E | 6 | 131.3 | 116.0 – 135.9 | 6.0 | 12.2 | |

| F | 3 | 120.1 | 116.4 – 122.5 | 2.7 | 8.4 | |

| G | 8 | 112.8 | 65.0 – 146.2 | 25.6 | 29.4 | |

| H | 5 | 148.8 | 117.6 – 184.0 | 19.1 | 24.2 | |

| All Manual Counters | 36 | 126.3 | 65.0 – 184.0 | 17.4 | 23.4 | |

| Imaging Software | 3 | 120.4 | 118.6 – 121.9 | 1.7 | 5.6 | |

| Expert Standard | 112.6 | |||||

For Picture Set B, the CVs according to center ranged from 2.3 to 25.6. The average CVs across pictures within Set B ranged from 8.4 to 29.4. Overall the total number of IEQs enumerated ranged from 65 to 184 with a CV of 17.4. The expert standard mean total IEq was 112.6.

For the software-assisted imaging analysis method, the counting results of the 3 technicians evaluating picture Set A, resulted in a CV of 2.3, and an average CV of 8.1. The total number of IEQs enumerated ranged from 385 to 402. For picture Set B, the software-assisted imaging analysis method resulted in a CV of 1.7 and a total IEQ count that ranged from 119 to 122.

Discussion

This multi-center study has established the accuracy, repeatability, and intermediate precision of the standard counting procedure of dithizone-stained human islets. It achieved its primary aim to validate this method of islet quantification as a release criterion for a human islet preparation for transplantation. The secondary aim of validating digital image analysis as a supplementary method for islet quantification was also reached. Image analysis tested at one experienced center surpassed each average of the three investigated parameters for standard counting obtained from all centers. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that image analysis is capable of providing more accurate and reproducible results than the established counting procedure.

The accuracy of IEQ determination was defined as a center’s bias in counting compared to the expert standard, which was obtained from three highly experienced islet counters by using the Delphi method to achieve consensus. Half of the centers overestimated picture set A and all centers overestimated picture set B. For picture set A, the centers that underestimated IEQ count were not significantly different from the expert standard whereas 3 of the 4 centers that overestimated were significantly different from the expert standard. Centers E and H significantly overestimated the count for both picture sets.

For image analysis, the mean count of IEQs was not different from the expert standard for picture set A but was different for set B. Even though the counts for picture set B were different from the expert standard only one center had a mean IEQ count closer to the expert standard. As overestimation of the total IEQ values was more common than underestimation, this would result in overestimation of the IEQ on average by about 10% with the standard method. In general, about 300,000 IEQ are required for an islet transplant to provide the minimum amount of 4,000 IEQ for a 70 kg recipient. Thus overestimation by 10% would qualify an islet lot with only 270,000 IEQ, and still provide a sufficient islet mass. However, the outlier of 30% overestimation would jeopardize the transplant outcome if such a lot were qualified. This clearly illustrates that training courses in IEQ counting are mandatory to improve the current variability in counting practice. It also shows the urgent need for a supplementary method, i.e. image analysis, to: (1) ensure more accurate counting for the technicians isolating islets, and (2) allows outside experts to verify the count as part of the quality assurance process.

Repeatability in IEQ quantification was assessed by the intra-observer CVs in IEQ determination from one repeat count in all of the centers, with 35 technicians participating. Average intra-technician CVs in IEQ determination with the standard method were 7.9% and 9.9% for picture sets A and B, respectively, whereas image analysis had average intra-technician CVs of 1.3 and 2.3 for the respective picture sets, and was therefore more consistent. Our intra-technician CVs for IEQ determination of <10% with the standard method is comparable to that reported by the Diabetes Research Institute, Miami, FL from three technicians, with a CV of 7.5% (12).

Intermediate precision was assessed from the inter-technician CVs in quantifying the IEQs. Average inter-technician CVs in IEQ measurement with the standard method were 12.9 and 17.4 for picture sets A and B, respectively, and with image analysis the CVs were only 2.3 and 1.7. Our data obtained with the standard counting method are similar to those reported from the Diabetes Research Institute, Miami, FL with an inter-technician CV of 31.0%, when taking into account that the CV between their samples was 12.5% (12).

Sampling error was not evaluated in our study, as we used photographs of dithizone-stained human islets as surrogates for islet samples. This was necessary, because it was not possible to provide the same islet samples for testing at each of the participating centers. As photographs were prepared from appropriate biological samples, representing islets of various sizes and shapes across the diameter range of <50 μm to >400 μm, they supplied the consistent sample required for precision determination as recommended in the ICH guideline Q2 (R1). The overall evidence supports the fact that digital image analysis was more accurate and consistent than the standard counting. This contrasts with previously published studies reporting a 25–30% difference between image analysis and standard method in IEQ assessment in pig and rat islet preparations (13, 14). However, these differences could be attributed to unconventional methods in calculating the IEQ that were based on areal density measurement of islet samples (13) and using the volume of an ellipse (14). Strict adherence to the international conventions for image analysis assessment of the IEQ in our study ensured comparability to the expert standard. Other reports using image analysis for evaluating islet isolation of mostly animal preparations also lacked the thorough approach of this study (15, 16).

Our study has established accuracy, repeatability, and intermediate precision for image analysis of human islets, meeting the analytical performance characteristics relevant to an active ingredient assay according to ICH guideline Q2(R1). Thus, there may be some advantages of image analysis worth the effort of the extra work. Instead of losing any record of the original islet sample as is inherent in the practice using standard microscopy assessment of islet preparations, the digital nature of the new imaging technique lends itself to storage of the original images of islet samples that can be analyzed and a permanent record kept in an electronic archive. Moreover, more advanced applications of image analysis have been already proposed, i.e. to apply an ellipsoid formula instead of a sphere, which might better reflect the islet shape and thus provide a better estimate of the islet volume (16).

The software program used in this study was well suited to the counting and sizing of the photographic islet preparations. This expert image analysis software is commercially available and supported by a worldwide scientific user and dealer network (www.solutions-zone.com). Its usefulness to quantify experimental and clinical histological specimens has been well established (17–22). The system was easy to use for our application and automated the IEQ calculations through the use of a customized spreadsheet, thereby reducing the possibility of operator-induced error.

In summary, this multi-center study validated the standard counting procedure using photographs of dithizone-stained islets by establishing the accuracy, repeatability, and intermediate precision of this method. In addition, digital image analysis was also validated by data from one experienced center, thereby qualifying digital image analysis as a useful supplementary method that may improve quality assurance of the islet product.

Acknowledgments

This study was generously supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

The authors acknowledge and thank William R. Clarke, PhD for critical review of the manuscript.

The authors would like to thank all who participated in the ICR Consortium Counting study by performing duplicate counts on both exercises: Adeola Adewola, Aisha Khan, Alejandro Alvarez, Alice Schwarznau, Beatrice Fournier, Chengyang Liu, Cheryl Smyth, Chris Groh, Deb Hullett, Hank Fortinberry, Itezia Iglesias-Meza, Jack O’Neil, Jaimie Sperger, Jan Chen, Joe Kuechle, Joel Szust, Jorge Montelongo, Kate Mueller, Keiko Omori, Lam Ho, Ling Jia Wang, Lisa Rodriguez, Luis Valiente, Matt Hanson, Meirigeng Qi, Moolky Nagabhushan, Nick Benschoff, Ross Haertter, Sebastian Danobeitia, Shusen Wang, Stacie Bryant, Tania Urrutia, Tom Gilmore, Willem Kühtreiber, Xiaomin Zhang, Xiojing Wang.

References

- 1.Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, et al. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1318–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirbolooki M, Lakey JRT, Kin T, Murdoch T, Shapiro AMJ. Aspects and challenges of islet isolation. In: Shapiro AMJ, Shaw JAM, editors. Islet transplantation and beta cell replacement therapy. New York: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc; 2007. pp. 115–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downing R, Scharp DW, Ballinger WF. An improved technique for the isolation and identification of mammalian islets of Langerhans. Transplantation. 1980;29(1):79–83. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198001000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricordi C, Gray DW, Hering BJ, et al. Islet isolation assessment in man and large animals. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1990;27(3):185–95. doi: 10.1007/BF02581331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ICH Harmonized Tripartide Guideline, Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology, Q2(R1). International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiao L, Gray D. In vitro staining of islets of Langerhans for fluorescence-activated cell-sorting. Transplantation. 1991;52(3):450–2. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199109000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiedor PS, Oluwole SF. Localization of endocrine pancreatic cells. World J Surg. 1996;20(8):1016–22. doi: 10.1007/s002689900155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konstantinidou A, Patsouris E, Kavantzas N, Pavlopoulos PM, Bouropoulou V, Davaris P. Computerized determination of proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in meningiomas. A comparison with non-automated method. Gen Diagn Pathol. 1997;142(5–6):311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Went P, Mayer S, Oberholzer M, Dirnhofer S. Plasma cell quantification in bone marrow by computer-assisted image analysis. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21(9):951–6. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sims AJ, Bennett MK, Murray A. Comparison of semi-automated image analysis and manual methods for tissue quantification in pancreatic carcinoma. Phys Med Biol. 2002;47(8):1255–66. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/8/303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denzin N, Lincoln Y. Entering the field of qualitative research. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. The landscape of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 1998. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann R, Fernandez LA, Bottino R, et al. Evaluation of islet isolation by a new automated method (Coulter Multisizer Ile) and manual counting. Transplant Proc. 1998;30(2):373–4. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)01314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lembert N, Wesche J, Petersen P, Doser M, Becker HD, Ammon HP. Areal density measurement is a convenient method for the determination of porcine islet equivalents without counting and sizing individual islets. Cell Transplant. 2003;12(1):33–41. doi: 10.3727/000000003783985214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girman P, Kriz J, Friedmansky J, Saudek F. Digital imaging as a possible approach in evaluation of islet yield. Cell Transplant. 2003;12(2):129–33. doi: 10.3727/000000003108746713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stegemann JP, O’Neil JJ, Nicholson DT, Mullon CJ. Improved assessment of isolated islet tissue volume using digital image analysis. Cell Transplant. 1998;7(5):469–78. doi: 10.1177/096368979800700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Girman P, Berkova Z, Dobolilova E, Saudek F. How to use image analysis for islet counting. Rev Diabet Stud. 2008;5(1):38–46. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2008.5.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carai A, Diaz G, Santa Cruz R, Santa Cruz G. Computerized quantitative color analysis for histological study of pulmonary fibrosis. Anticancer Res. 2002;22(6C):3889–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wexler EJ, Peters EE, Gonzales A, Gonzales ML, Slee AM, Kerr JS. An objective procedure for ischemic area evaluation of the stroke intraluminal thread model in the mouse and rat. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;113(1):51–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00476-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benali A, Leefken I, Eysel UT, Weiler E. A computerized image analysis system for quantitative analysis of cells in histological brain sections. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;125(1–2):33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xavier LL, Viola GG, Ferraz AC, et al. A simple and fast densitometric method for the analysis of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the substantia nigra pars compacta and in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2005;16(1–3):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carnier P, Gallo L, Romani C, Sturaro E, Bondesan V. Computer image analysis for measuring lean and fatty areas in cross-sectioned dry-cured hams. J Anim Sci. 2004;82(3):808–15. doi: 10.2527/2004.823808x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarvazyan N. A new approach to assess viability of adult cardiomyocytes: computer-assisted image analysis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30(2):297–301. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]