Abstract

The prion protein (PrP) takes up four to six equivalents of copper in its extended N-terminal domain, composed of the octarepeat (OR) segment (human sequence residues 60–91) and two mononuclear binding sites (at His96 and His111; also referred to as the non-OR region). The OR segment responds to specific copper concentrations by transitioning from a multi-His mode at low copper levels to a single-His, amide nitrogen mode at high levels (Chattopadhyay et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 127, 12647–12656, 2005). The specific function of PrP in healthy tissue is unclear, but numerous reports link copper uptake to a neuroprotective role that regulates cellular stress (Stevens et al. PLoS Pathogens, 5(4): e1000390, 2009). A current working hypothesis is that the high occupancy binding mode quenches copper’s inherent redox cycling, thus protecting against the production of reactive oxygen species from unregulated Fenton type reactions. Here, we directly test this hypothesis by performing detailed pH-dependent electrochemical measurements on both low and high occupancy copper binding modes. In contrast to the current belief, we find that the low occupancy mode completely quenches redox cycling, but high occupancy leads to the gentle production of hydrogen peroxide through a catalytic reduction of oxygen facilitated by the complex. These electrochemical findings are supported by independent kinetic measurements that probe for ascorbate usage and also peroxide production. Hydrogen peroxide production is also observed from a segment corresponding to the non-OR region. Collectively, these results overturn the current working hypothesis and suggest, instead, that the redox cycling of copper bound to PrP in the high occupancy mode is not quenched, but is regulated. The observed production of hydrogen peroxide suggests a mechanism that could explain PrP’s putative role in cellular signaling.

1. INTRODUCTION

The misfolding and aggregation of the prion protein (PrP), a membrane-bound glycoprotein present in the central nervous system (CNS) of mammalian and avian species, leads to the development of the prion diseases.1,2 The human forms of prion diseases,3 including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and kuru, share similar neuropathologies to other more prevalent neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD).4,5 PrP has been shown to interact with a number of divalent metal ions,6,7 and with moderate to high affinity to Cu2+ and Zn2+.7,8 The linkage between PrP and bioavailable Cu2+ is particularly well established by in vitro and in vivo9 studies and described in a number of recent reviews.10–14 Although copper is an essential metal and exists in a number of proteins, free Cu2+ exhibits high cytotoxicity, stemming from its ability to initiate redox cycling, in turn generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) via the Harber-Weiss reaction:15–18

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The highly toxic and reactive hydroxyl radical (OH•) can readily damage DNA and proteins and cause lipid peroxidation. Reaction (3) is also referred to as a Fenton-like reaction because of its similarity to the Fenton reaction with Fe2+ and H2O2 as the reactants.16

In biological milieu, free or bound Cu2+ could initiate another redox cycle, which is dependent on the thermodynamic properties of the reactants and the structure of the Cu2+ complexes. The cycle starts with the reduction of free or Cu2+ bound to a ligand (L) by a biological reductant. The resultant Cu+ can be subsequently oxidized by O2, generating H2O2 as a product. Using ascorbic acid (AA, which exists as ascorbate at neutral pH and oxidizes to dehydroascorbate or DA) as a representative reductant, this cycle can be described as:19–22

| (4) |

| (5) |

Notice H2O2 produced in reaction (5) can in turn react with any remaining free or bound Cu2+ through reactions (1)–(3) to produce OH•.

Given the abundance of oxygen23,24 and biological reductants (e.g. AA and glutathione or GSH) in the CNS (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in particular), if a redox active metal were not properly regulated, the large quantity of ROS produced by the Cu2+-initiated redox cycling would likely lead to significant oxidative damage. On the basis that PrP is a Cu2+-binding protein,9 a major biological function of PrP has been hypothesized to complex Cu2+ to attenuate or buffer its redox activity so that ROS is prevented from forming, or converted into less harmful species.11,12 A unique feature of PrP is that distinct Cu2+ binding modes are populated in response to different Cu2+ concentrations. PrP contains a highly conserved repeat of an octapeptide (OP) sequence within its N-terminal domain that constitutes its primary sites for Cu2+ uptake.11,12 Human PrP has four tandem copies of the specific sequence PHGGGWGQ (referred to as the octarepeat11 or OR within residues 60–91). In vitro studies have shown that when the concentration ratio between PrP and Cu2+ is larger than 1:1, four histidines (His) in the OR domain coordinate a single Cu2+ center forming the low Cu2+ occupancy binding mode OR–Cu2+ (Figure 1).25 When the Cu2+ concentration rises to four or more equivalents per protein, each of the four OPs binds one Cu2+, giving rise to the so-called high occupancy or OR–Cu2+4 (Figure 1).25 In OR–Cu2+4, each Cu2+ is ligated by one His, the amide nitrogens on the two adjacent and deprotonated glycines, and a glycine carbonyl.25 The OR–Cu2+ and OR–Cu2+4 binding modes take up Cu2+ with highly disparate dissociation constants (0.1 nM for the former and ~10 μM for the latter) and consequent negative cooperativity.11,26 Immediately outside of the OR domain, the segment encompassing two His residues (in human PrP they are His96 and His111 and in mouse PrP His96 and His110) can also bind Cu2+. This segment is referred to as the non-OR Cu2+-binding site.27–29 It is recently shown that when solution pH becomes sufficiently low (~6.0 or lower), the wild-type (WT) PrP binds a single Cu2+ in the OR–Cu2+ mode.30 This is conceivable since His imidazoles have a lower pKa than glycine amide nitrogens (even when they are bound to metal ions), and consequently the Gly amide nitrogens, once protonated, are the first to lose their metal-binding ability.11

Figure 1.

Structures of OR–Cu2+ (low Cu2+ occupancy) and OR–Cu2+4 (high Cu2+ occupancy).

The multiple binding modes between Cu2+ and PrP and their disparate affinities have long been linked to the various functions of PrP11,12 in modulating or inhibiting Cu2+ redox cycling and oxidative stress under different conditions. For example, a recent analysis of insertional mutations in the OR domain linked early onset prion disease to hindered copper uptake and decreased population of the high occupancy mode.31 Delineation of the respective roles and/or functions of the distinct binding copper binding modes requires a clear understanding of their redox behaviors, which has been confounded by several contradictory studies. For example, Miura et al.32 and Ruiz et al.33 reported that the tryptophan (Trp) residues in the OR domain appears to readily reduce Cu2+ to Cu+ at both physiological and acidic pH. It was proposed that the OR–Cu2+ mode may allow one Trp residue to be in close vicinity to the Cu2+ center for a facile Cu2+ reduction.32 However, many EPR studies have found that the Cu2+ centers bound by OR in both the low and high occupancies (even the transitory modes or stoichiometries such as OR–Cu2+2 and OR–Cu2+3) are stable.25,26,34,35 Bonomo et al. determined the redox potential of the OP–Cu2+ complex, which contains only one OP but has an equivalent Cu2+ coordination to that in OR–Cu2+4.36 The surprisingly negative potential (~ −0.3 V vs. NHE) would silence the redox cycling of bound Cu2+ completely as it is lower (more negative) than those of many biological relevant reductants (e.g., AA and GSH). In other words, reaction (4) would be fully quenched. This contradicts the finding that OR–Cu2+4 catalyzes the production of OH• from H2O2.37 In addition, Nishikimi and coworkers37 and Requena and coworkers38 demonstrated that the Cu2+ centers in the OR domain are responsible for the oxidation of AA to DA. Owing to the above conflicting results, it has been difficult to rationalize cell-based and in vivo findings regarding the functions of PrP and its copper complexes.

A current working hypothesis, based on some of these published reports,32,33,39 suggests that the high occupancy binding mode (OR–Cu2+4) quenches the redox cycling of free Cu2+, thus protecting against the production of ROS.11,39 In addition, this hypothesis does not consider the detailed cellular milieu in which the catalytic cycle represented by reactions (4) and (5) might be more relevant. Such a cycle can proceed only if (I) the redox potential of L–Cu2+ is higher than that of the biological reductant and (II) the redox potential of L–Cu+ is lower than that of the O2/H2O2 couple. In this work, we determined redox potentials of OR–Cu2+, OR–Cu2+4 and non-OR–Cu2+ under an anaerobic environment and compared their voltammetric characteristics to those observed in the presence of oxygen. We demonstrate that the redox cycling observed for these complexes can be reliably predicted from redox potentials and verified by measurements of the oxidation of AA (as a common reductant) and H2O2 generated from the catalytic reduction of O2. Our finding clearly shows that redox cycling of Cu2+ is highly dependent on the binding mode of the PrP–Cu2+ complexes. Moreover, contrary to the current hypothesis, we find that OR–Cu2+ is the binding mode that completely quenches any copper redox cycling. OR-Cu2+4 leads to the gentle and controlled production of H2O2, which may serve as a signaling molecule to initiate various cellular events. We also examined the redox reactions of these complexes at different pH to assess how redox activity may be modulated by PrP trafficking through early and late endosomes.

2. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

2.1 Materials

The octapeptide PHGGGWGQ (OP), an OR-containing peptide PrP(23–28, 57–91), and the PrP(91–110) peptide representing the non-OR site in mouse PrP, were all prepared using solid-phase fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) methods.34, 40 These peptides were acetylated at their N-termini and amidated at C-terminus. The crude products were purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and characterized by mass spectrometry. The α-synuclein (α-Syn) peptide, α-Syn(1–19), was also synthesized and purified similarly. Amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide Aβ(1–16) was purchased from American Peptide Co. Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA). Table 1 lists the five peptides used in this work.

Table 1.

Sequences of peptides used in this work

| KKRPKPWGQ(PHGGGWGQ)4 | PrP(23–28, 57–91) or OR |

| PHGGGWGQ | OP |

| GGGTHNQWNKLSKPKTNLKH | PrP(91–110) or non-OR |

| DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQK | Aβ(1–16) |

| MDVFMKGLSKAKEGVVAAA | α-Syn(1–19) |

2.2 Electrochemical Measurements

Voltammetric measurements of OR–Cu2+, OR–Cu2+4, and non-OR–Cu2+ were performed on a CHI 411 electrochemical workstation (CHI Instruments, Austin, TX) using a homemade plastic electrochemical cell. A glassy carbon disk (3 mm in diameter), a platinum wire, and a Ag/AgCl electrode served as the working, auxiliary, and reference electrodes, respectively. The electrolyte solution was a 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) comprising 50 mM Na2SO4. Prior to each experiment, the glassy carbon electrode was successively polished with diamond pastes of 1 and 0.3 μm in diameter (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL) and sonicated in deionized water. Voltammetric experiments under the oxygen-free condition were carried out in a glove box (Plas Lab, Lasing, MI) that had been thoroughly purged with and kept under N2. The oxygen concentration in solution housed in this glove box was measured to be less than 0.05 ppm by a portable conductivity meter (Orion 3-Star Plus; Thermo Electron Corp., MA). Voltammetry was also performed in solutions purged with O2 for a few minutes and the concentration of O2 was maintained at ca. 8.5 ppm. In order to minimize free Cu2+ in solution and avoid its interference on the voltammograms of complexes formed between Cu2+ and the PrP peptides, [Cu2+]/[OR] was maintained at 0.9/1 for OR–Cu2+ and 3.6/1 for OR–Cu2+4

2.3 Kinetic measurement

The AA oxidation rate was determined by monitoring the change in AA absorbance at 265 nm using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Cary 100 Bio, Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA). The absorbance values plotted have excluded those contributed by the individual peptides at 265 nm (measured in separate peptide solutions of same concentrations). The kinetic experiments were conducted at 25 °C in phosphate buffer, as described by our previous studies.22 To form exclusively OR–Cu2+, it is critical to maintain the [OR]/[Cu2+] ratio much higher than 1:1 so that the amount of free Cu2+ remaining in solution is negligible.

2.4 Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide

The H2O2-detection kit was purchased from Bioanalytical System Inc. (West Lafayette, IN)41 and the detection was conducted in a thin-layer electrochemical flow cell (Bioanalytical System Inc.) using a hydrogel-peoxidase-modified glassy carbon electrode by following our previously published protocol.40 Briefly, 100 μM of a given peptide was mixed with Cu2+ (5 μM) for 10 min. The resultant mixture was then incubated with AA (200 μM) for 2 h. The sample mixture was diluted five-fold with phosphate buffer, prior to being injected into the electrochemical flow cell.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Redox behavior of Cu2+ complexes with PrP peptides in aerobic and anaerobic solutions

The cyclic voltammogram (CV) of OR in an oxygen-free solution reveals that it is redox inactive between −0.3 and 0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl (dotted line curve in Figure 2A). In contrast, voltammograms of OR–Cu2+ exhibit a redox wave with the midpoint potential (E1/2)42 at 0.126 V (black curve in Figure 2A). The potential value is about 0.05 V higher than that of a complex formed between a cyclic peptide (Gly-His)4 and copper43 for mimicking the putative role of superoxide dismutase-like activity of PrP.44, 45 It is also 0.06 V lower than the theoretically calculated redox potential of OR–Cu2+.46 Detailed CV studies (Figure S1 and Table S1 in the Supporting Information) indicate that the cycling between the Cu2+ and Cu+ centers is quite reversible. This CV wave remains essentially unchanged when the solution is saturated with O2 (red curve). Notice that the higher background of the CV at potential beyond −0.2 V is attributable to electrochemical reduction of dissolved O2. Interestingly, the voltammetric behavior of OR–Cu2+4 (Figure 2B) is different from that of OR–Cu2+ in the following aspects. First, in the absence of O2, E1/2 (black curve) of OR–Cu2+4 was determined to be −0.025 V, a shift by 0.151 V in the negative direction with respect to that of OR–Cu2+. A small shoulder wave is discernable at ca. 0.075 V, which is 0.051 V more negative than the wave of OR–Cu2+. The two waves are more distinguishable in their differential pulse voltammorams (Figure S2). We assign the wave at −0.025 V to OR–Cu2+4 and that at 0.051 V to the transitory binding modes in which the stoichiometry between OR and Cu2+ ranges between 1:2 and 1:3.25 No Cu0 stripping peak (vide infra) was observed, suggesting that free Cu2+ in the mixture is minimal. Previously an EPR study conducted by one of us25 has shown that OR–Cu2+4 coexists with these less abundant transitory species. The second aspect is that, when O2 is present in solution, the OR–Cu2+4 CV becomes sigmoidal (i.e., the reduction peak is enhanced at the expense of the oxidation wave). Such a behavior was also observed for non-OR–Cu2+ (red curve in Figure 2C), albeit the latter exhibits a plateau at an even more negative potential. These sigmoidal CV waves have the same characteristics as that of free Cu2+ (red curve in Figure 2D), which is indicative of a catalytic process42 in which the electrogenerated Cu+ is rapidly reoxidized by O2 in solution. Therefore, the Cu+ centers in both OR–Cu2+4 and non-OR–Cu2+ are oxidizable by O2, a direct consequence of the negative (cathodic) shifts of their redox potentials with respect to that of OR–Cu2+. In deaerated solution (Figure 2D), there is no oxygen to regenerate Cu+ reduced from free Cu2+ and consequently Cu+ is further reduced to Cu0 (since Cu+ is easier to reduce than Cu2+).42 Cu0 deposited onto the glassy carbon electrode can then be oxidized back to Cu2+ during the scan reversal. The sharp anodic peak is resulted from the stripping of the electrodeposited Cu0.42

Figure 2.

Cyclic voltammograms of (A) OR–Cu2+, (B) OR–Cu2+4, (C) non-OR–Cu2+ and (D) free Cu2+ in N2-saturated (black curve) and O2-purged solutions (red curve), respectively. The Cu2+ concentration in all cases was 90 μM, while the OR and non-OR concentrations were 100, 25, and 100 μM in panels (A), (B) and (C), respectively. The dotted line curve in (A) corresponds to the CV of OR. The scan rate was 5 mV/s.

Another point worth noting is that the shift of the plateau of the red curve in Figure 2C relative to that in Figure 2B is originated from the more negative redox potential of non-OR–Cu2+. In the absence of O2 (black curve in Figure 2C), the non-OR–Cu2+ CV is less reversible, as evidenced by a smaller anodic peak compared to its cathodic counterpart and a wider separation in potential between the two peaks than that in the CV of OR–Cu2+4 (cf. more details in Table S2).

3.2 pH-dependent redox behavior of PrP–Cu2+ complexes

An interesting property of PrP and its peptidic variants is that their Cu2+-binding is sensitive to solution pH.11,12,30,32 At values lower than physiological pH (e.g., ~6.5 or lower),30 the amide nitrogens become protonated, disfavoring the OR–Cu2+4 binding mode. However, for OR–Cu2+, an even lower pH is required to release the only Cu2+ ion, owing to the fact that Cu2+ is strongly coordinated by the four His residues in the OR domain (cf. Figure 1). We therefore examined the voltammetric responses of OR–Cu2+, OR–Cu2+4, and non-OR–Cu2+ at different pH values and also studied the effects of O2. Panels (A) and (B) in Figure 3 are overlaid voltammograms of OR–Cu2+ and OR–Cu2+4 in deaerated solutions at representative pH values, respectively. As can be seen, CVs of OR–Cu2+ are essentially congruent between pH 7.4 and 6.5 and only till pH 6.0 does the CV begin to show a drastic change. At pH 6.0 and lower, the CV is analogous to that of free Cu2+ under anaerobic condition (cf. the black curve in Figure 2D) and peaks associated with OR–Cu2+ are no longer observable. For OR–Cu2+4, the Cu2+ release occurs at a higher pH (6.5), consistent with the abovementioned fact that protonation of the Gly amide nitrogens destabilizes the OR–Cu2+4 complex. A close examination of the CVs collected at pH 7.4 (black curve) and 7.0 (red curve) reveals that even with such a small pH variation, some Cu2+ release appears to have taken place. This is reflected by the small increase of the wave at around 0.051 V (red curve), which is given rise by the transitory species such as OR–Cu2+2 and/or OR–Cu2+3. As mentioned above, these species are better resolved in their differential pulse voltammograms (Figure S2). Thus, as soon as some Cu2+ ions are released from OR–Cu2+4, OR might have rearranged to bind the remaining Cu2+ ions with the available His residue(s). As for non-OR–Cu2+, a 0.4-unit pH decrease causes the redox wave to shift by 0.01 V in the anodic direction (cf. the red and black curves in Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammograms of (A) OR–Cu2+, (B) OR–Cu2+4, and (C) non-OR–Cu2+ at different pH values. In panel (A) the curves correspond to pH 7.4 (black), 6.5 (red) and 6.0 (blue) and in panels (B) and (C) the curves correspond to 7.4 (black), 7.0 (red) and 6.0 (blue). The concentrations of Cu2+ and peptides used are the same as those in Figure 2. Panel (D) contrasts the voltammograms of OR–Cu2+ at pH 5.5 in the presence (red curve) and absence (black curve) of O2.

To verify that in aerated solution Cu2+ released from the complexes behaves the same as free Cu2+ in ligand-free solutions, we also collected CVs of the three complexes at lower pH values. Figure 3D compares the CVs of OR–Cu2+ in deaerated (black) and aerated (red) solutions at pH 5.5. The trend is essentially the same as that of free Cu2+ (cf. Figure 2D). OR–Cu2+4 or non-OR–Cu2+ also displayed very similar behaviors at higher pH (data not show). Thus Cu2+ ions, once released from these complexes, are capable of initiating redox cycles. The relevance of our data to the hypothesis that PrP acts as a Cu2+ transporter via endocytosis is described in the Discussion section.

3.3 Relationship between the Cu2+ binding mode and the H2O2 production

Through voltammetric studies of Cu2+ complexes with amyloid β (Aβ) peptides,47 which are linked to the neuropathology of AD, and α-synuclein (α-syn),40 which is believed to lead to the development of PD, we have demonstrated that H2O2 is indeed a product generated through reactions (4) and (5).40,47 Therefore we are interested in probing whether H2O2 can be generated by one or more of the PrP–Cu2+ complexes. In Table 2, we contrast the redox potentials of OR–Cu2+, OR–Cu2+4, and non-OR–Cu2+ to those of the O2/H2O2 and AA/DA couples. It is evident that, from the thermodynamic viewpoint O2 is incapable of oxidizing OR–Cu+. In other words, the single Cu+ center is so “stabilized” by OR that O2 cannot turn it over to Cu2+ (i.e., reaction (5) would not occur). In contrast, both the OR–Cu2+4 (high occupancy) and non-OR–Cu2+ modes have lower redox potentials than the O2/H2O2 couple and therefore are expected to behave similarly to the Cu2+ complexes of Aβ and α-syn to facilitate the catalytic O2 reduction.

Table 2.

Redox potentials of Cu2+ complexes with select amyloidogenic molecules and biological redox couples.

| Species | E1/2 or E0 vs. Ag/AgCl | vs. NHE | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR–Cu2+/OR–Cu+ | 0.126 V | 0.323 V | This work |

| O2/H2O2 | 0.099 | 0.296 | 48 |

| Aβ–Cu2+/Aβ–Cu+ | 0.080 | 0.277 | 47 |

| PrP–Cu52+/PrP–Cu5+ | 0.070 | 0.267 | 30 |

| α-Syn–Cu2+/α-Syn–Cu+ | 0.018 | 0.215 | 40 |

| OR–Cu2+ 4/OR–Cu+4 | −0.025 | 0.172 | This work |

| Free Cu2+/Cu+ | −0.040 | 0.157 | 42 |

| non-OR–Cu2+/non-OR–Cu+ | −0.087* | 0.110* | This work |

| AA/DA | −0.145 | 0.052 | 49 |

| GSH/GSSG | −0.425 | −0.228 | 50 |

Accuracy is affected by the less reversible redox wave of non-OR–Cu2+.42

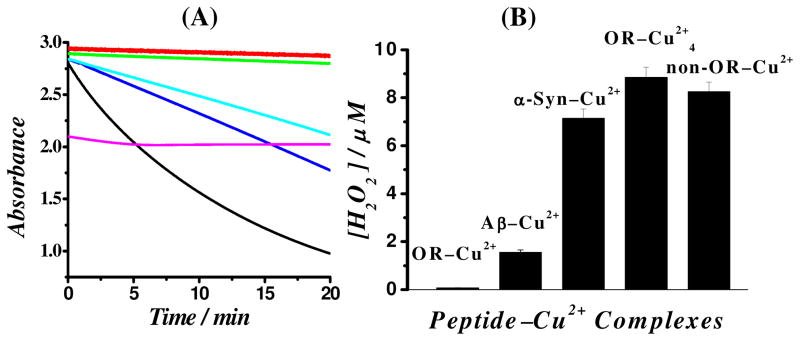

The above thermodynamic prediction was verified by two experiments. First, we determined the kinetics of AA oxidation by O2 in the presence of OR–Cu2+, OR–Cu2+4, or non-OR–Cu2+ by monitoring the change of AA absorbance at 265 nm. As shown by the green curve in Figure 4A, the rate of AA autooxidation was found to be exceedingly slow (0.051 ± 0.004 nM s−1). The rate did not change with the addition of 5 μM OR–Cu2+ (0.048 ± 0.004 nM s−1), but AA becomes rapidly consumed when the same amount of OR–Cu2+4 (42.2 ± 4.7 nM s−1), non-OR–Cu2+ (34.8 ± 3.7 nM s−1) or free Cu2+ (191 ± 17.2 nM s−1) is present. However, AA can be instantaneously and significantly oxidized by OR–Cu2+ at a concentration stoichiometrically more comparable to that of AA. Notice that the absorbance of a 200 μM AA solution decreased by ~28% immediately upon being mixed with 100 μM OR–Cu2+ (magenta curve). The oxidation of AA is quantitative, since such a decrease is close to the theoretical value (~25%). This observation is also confirmed by a separate differential pulse voltammetric experiment (Figure S3). Thus, the inability of O2 to oxidize OR–Cu+ results in a halt of the Cu2+ redox cycling, preventing additional AA from being continuously oxidized. In the second experiment, we demonstrated that (1) H2O2 is indeed a product of the redox cycle and (2) the amount of H2O2 produced can be correlated to the redox potential of the Cu2+ complexes with select peptides. Specifically, using a commercial electrochemical H2O2 detection kit,40 we found that after 2 h of reaction the amount of H2O2 generated in the presence of OR–Cu2+ is essentially negligible, whereas H2O2 was detected in the presence of other species. The amount of H2O2 increases in the order of Aβ(1–16)–Cu2+ < α-syn(1–19)–Cu2+ < non-OR–Cu2+ < OR–Cu2+4 (Figure 4B), which is largely consistent with the order of the redox potentials of the respective complexes (Table 2). It is worth noting that we chose the Cu2+-binding peptidic segments of the full-length Aβ peptide and the α-syn protein, because the resultant complexes are more comparable to OR–Cu2+ or OR–Cu2+4 in terms of their sizes and O2 accessibility to the copper center.47

Figure 4.

(A) Change of AA (200 μM) absorbance as a function of reaction time in the absence (green curve) and presence of different Cu2+-containing species: OR–Cu2+ (red curve), non-OR–Cu2+ (cyan), OR–Cu2+4 (blue), and free Cu2+ (black). The magenta curve corresponds to the AA absorbance variation recorded after the addition of 100 μM OR–Cu2+ to 200 μM AA solution (B) Amounts of H2O2 generated by OR–Cu2+, Aβ(1–16)–Cu2+, α-syn(1–19)–Cu2+, OR–Cu2+4, and non-OR–Cu2+. [Cu2+] was 5 μM, and concentrations of the peptide molecules were all 100 μM except for the solution of OR–Cu2+4 wherein [OR] = 1.25 μM.

3.4 Time and pH dependences of the H2O2 production

At different solution pH, we also monitored the production of H2O2 as a function of time. Again, OR–Cu2+ generates little H2O2 (even over a period of 2 h as shown by Figure 5A). In contrast, H2O2 generated by OR–Cu2+4 or non-OR–Cu2+ increases gradually with time. However, the amounts of H2O2 produced by these complexes are substantially lower than that by free Cu2+, especially at the beginning of the redox cycle (magenta curve in Figure 5A). We also measured the amount of H2O2 generated by the Cu2+-glutamine complex, on the basis that glutamine is the most abundant amino acid in CSF (more than 10 times higher than other amino acids and also albumin, a major Cu2+-transport protein24). Using 1012.5 for the formation constant of the Cu(Gln)2 complex51 and adjusted to pH 7.0, the Cu(Gln)2 complex has an affinity constant of 0.32 μM, which is between those of OR–Cu2+ (0.1 nM) and OR–Cu2+4 (7.0–12.0 μM)26. That much more H2O2 was generated by the Cu(Gln)2 complex (see the green curve in Figure 5A) suggests that, in addition to the binding affinity, other structural factors (e.g., accessibility to the Cu2+ center(s) by cellular reductants and O2) are also important. Thus, OR–Cu2+ completely quenches the Cu2+ redox cycling, while OR–Cu2+4 and non-OR–Cu2+ are capable of reducing the amount of H2O2 production.

Figure 5.

(A) Time-dependence of H2O2 generation in different solutions: OR–Cu2+ (black), OR–Cu2+4 (red), non-OR–Cu2+ (blue), Cu2+/glutamine (green) and free Cu2+ (magenta). All solutions contained 5 μM Cu2+ and 200 μM AA and the ligand concentration was 100 μM except for the solution of OR–Cu2+4 wherein [OR] = 1.25 μM. (B) Variations of [H2O2] generated by OR–Cu2+ in solutions of different pH values: 7.4 (black), 6.5 (red), 6.0 (green) and 5.5 (blue). Each data point is the average of three replicates and the error bars are the standard deviations.

The initial sharp rises of the blue and green curves in Figure 5A can be attributed to the rapid production of H2O2 via reactions (4) and (5) by free Cu2+ or the glutamine-Cu2+ complex. The more gradual decay is a convoluted result of the continuous H2O2 production via this redox cycle and the decomposition of H2O2 by free Cu2+ or the glutamine-Cu2+ (Glu–Cu2+) complex via reactions (1)–(3). Thus, as H2O2 builds up in the solution, reactions (1)–(3) will accelerate to decrease the amount of H2O2. However, in this case the more reactive and pernicious hydroxyl radicals are formed. The biological implication of the H2O2 generation as well as the complete inhibition of the H2O2 and hydroxyl radical productions by these Cu2+ complexes will be presented in the Discussion section.

Finally, we determined the time dependence of H2O2 production by the Cu2+ complexes at different solution pH. Figure 5B displays representative results measured and plotted for OR–Cu2+ at pH 7.4, 6.5, 6.0 and 5.5. When Cu2+ is bound, no (for OR–Cu2+) or a small amount of H2O2 (for OR–Cu2+ and non-OR–Cu2+; data not shown) was produced. However, as the solution pH is lowered, all complexes exhibit the same trend as depicted by the green and blue curves in Figure 5B, suggesting that Cu2+ released from these complexes becomes predominant in producing H2O2 and possibly hydroxyl radicals. Thus, at physiological pH, all the binding domains possess the ability of preventing a large amount of H2O2 from being produced and completely annihilating the possibility of hydroxyl radical generation. This aspect will be reiterated below in connection with the discussion of the possible functions of PrP.

4. DISCUSSION

Using carefully controlled anaerobic and aerated solutions, we conducted a systematic investigation on the electrochemical behaviors of OR–Cu2+, OR–Cu2+4, and non-OR–Cu2+. Comparison of the respective redox potentials of these complexes to those of the O2/H2O2 and AA/DA couples (cf. Table 2) clearly indicates that, thermodynamically, the Cu2+ centers in these complexes can all be reduced by common cellular reductants (e.g., AA and GSH). However, the occurrence of the Cu2+ redox cycle described by reactions (4)–(5) to generate H2O2 also requires the Cu+ centers be oxidizable by O2. Based on the shifts in the reduction potentials of the complexes with respect to that of free Cu2+, we determined that in the OR–copper complex (low occupancy), binding of Cu+ by OR is about three orders of magnitude stronger than that of Cu2+ (Supporting Information). Thus, by significantly shifting the redox potential of the bound Cu2+ in the anodic direction, the low occupancy binding mode completely inhibits the H2O2 generation. In contrast, binding affinities of Cu2+ and Cu+ in the high occupancy mode are comparable. We found that non-OR binds Cu+ about 4.7 times less strongly than Cu2+ (Supporting Information). As a consequence, non-OR–Cu2+ can also facilitate the H2O2 generation. The reported redox potentials of complexes of shorter non-OR peptides with copper are 0.24 V for the GGGTH–Cu2+ complex29 and 0.32 V for the GGGTHSQW–Cu2+ complex52, both of which are much higher than 0.110 V we measured for non-OR–Cu2+. From the thermodynamic viewpoint, GGGTHSQW–Cu2+ would not be capable of facilitating the redox cycling of Cu2+ if its redox potential were 0.32 V. The results from both the UV-vis spectrophotometric measurements of AA oxidation and electrochemical quantification of H2O2 (Figure 4) are fully consistent with our thermodynamic reasoning. This firmly establishes a correlation between a specific Cu2+ binding mode in PrP and the protein’s ability to ameliorate oxidative stress. It is worth mentioning that the properties of the complexes not only depend on what and how many amino acid residues are involved in the binding, but also are governed by the environment and steric hindrance under which the residues are bound to the Cu2+ center. We noticed that the complex formed between (Gly-His)4 and Cu2+ has a potential that is 0.05 V more negative than OR–Cu2+.43 Such a difference is expected to make this complex behave similarly to the Aβ–Cu2+ complex (cf. Table 2), leading to the Cu2+ redox cycling to produce H2O2. It is also interesting to note that the redox potential of OR–Cu2+ (0.323 V vs. NHE; cf. Table 2) is very close to that of superoxide dismutase or SOD (0.32 V).43 While this may be used to argue for the SOD-like behavior of the PrP–Cu2+ complex,44 we should point out that the reported “SOD-like activity” of PrP–Cu2+ is at least two orders of magnitude smaller than that of native SOD.45 In addition, there are other large differences in structures and properties between the PrP–Cu2+ complex and native SOD that make the correlation of the PrP–Cu2+ complex to SOD questionable.11,12

The significance of our findings is three fold. First, with a better understanding of the redox behavior of the PrP–Cu2+ complexes, several major discrepancies in the literature may now be clarified. As mentioned in the introduction, the current paradigm suggesting that OR–Cu2+4, instead of OR–Cu2+, is the more effective binding mode for quenching Cu2+ redox cycling now becomes questionable.11,12 Our new paradigm provides theoretical supports for the work of Shiraishi et al.37 and Requena and coworkers38 in that AA can be directly oxidized by both OR–Cu2+4 and OR–Cu2+, but only the latter of which completely quenches the copper redox cycling. Regarding the reduction of Cu2+ by Trp inherent in the OR domain of PrP, we believe that the use of bathocuproine (BC) to assay the redox activity of PrP-copper complexes can be problematic. Despite the cautions advocated by Sayre53 and Ivanov et al.54, BC and its derivatives are still widely used for studying reduction of Cu2+ bound by biomolecules to Cu+. With a strong binding affinity, BC can seize Cu2+ from certain biomolecules and bind it in the form of (BC)2–Cu2+, which has a much higher oxidation potential than free Cu2+ and many other Cu2+ complexes.53 Consequently, when oxidizable ligands are present in the system (e.g., His, Tyr, Trp, and Cys residues on protein molecules), Cu+ is produced and bound by BC, with the simultaneous oxidation of these redox-active moieties. Another important issue is that the Cu2+ redox cycling (or lack of) shown by reactions (4) and (5) is not only dependent on the conversion of Cu2+ to Cu+ by an endogenous reductant, but also governed by the requirement that Cu+ remaining bound to PrP must then be oxidized back by O2 to Cu2+. Thus, to simply ascribe the absence or presence of a redox cycle to the “stabilization” of Cu2+ or Cu+ might not be the most accurate interpretation on the role of PrP in inhibiting Cu2+-induced ROS production. Finally, OR–Cu2+ is also more effective in inhibiting ROS production than the Aβ–Cu2+ and α-syn–Cu2+ complexes. High levels of Cu2+ have been found to be complexed by Aβ peptides in senile plaques55 and by α-syn in CSFs of patients56. Such observations have been used to suggest the pro- or anti-oxidation functions of these amyloidogenic species.17,55–59

The second outcome of our study is that the voltammetric responses of the three PrP–Cu2+ complexes each exhibit a different dependence on solution pH. The pH sensitivity of PrP–Cu2+ and the demonstration that high copper levels (e.g., 100 μM60) stimulate PrP endocytosis have been used to advance the hypothesis that PrP may function as a copper transporter. Once becoming internalized and incorporated by endosomes, Cu2+ could be released from the complex due to the acidic environment of the endosome.11,32 Although this copper-transport model is still under debate11,12 and the fate of internalized PrP or the bound and released Cu2+ is not known, our results suggest that PrP with Cu2+ bound in different modes may undergo different endocytotic processes. It is well established that pH is only slightly acidic (~6.3–6.8) in the tubular extension of the early endosome, whereas it decreases from 6.2 to ~5.5 in the lumen of multi-vesicular bodies.61 The tubular extension is mainly responsible for the recycling of proteins, while the multi-vesicular bodies, a feature characteristic of the late endosome, are involved in sorting its cargo to the degradation pathway.62 PrP fully loaded with Cu2+, once encountering the slightly acidic environment of the early endosome, can release most of its Cu2+ complement. In contrast, Cu2+ is strongly withheld by OR in the OR–Cu2+ mode, even at the much lower pH inside the multi-vesicular bodies. Indeed, Brown and colleagues recently showed that at pH 5.5 or even lower, a single Cu2+ remains bound to the WT PrP in the OR domain. At a higher pH (~6.0), non-OR becomes capable of binding Cu2+ and the incorporation of additional Cu2+ ions into the OR domain occurs only after the solution pH has approached to the physiological value.30 Based on our pH-dependence study (Figure 3), we hypothesize that Cu2+ released from the fully loaded PrP, through either subsequent complexation with other copper-binding proteins or generation of H2O2, may trigger the accumulation of PrP in the tubular extension of the early endosome, which ultimately leads to recycling of PrP back to plasma membrane. As for PrP containing only one Cu2+, it could remain bound to PrP even in the late endosome, which is eventually fused with the lysosome for the final protein and metal degradation.62

Finally, we note that the distinct electrochemical features associated with each binding mode may provide insight into PrP function. PrP has been suggested to serve as a neuroprotectant by scavenging weakly complexed Cu2+ in vivo and thereby alleviating oxidative stress that might be induced by free Cu2+.31,63 The gradual generation of H2O2 by either OR–Cu2+4 or non-OR–Cu2+ does not contradict the proposed neuroprotecting function of PrP. As can be seen from Figure 5, the amount of H2O2 generated by OR–Cu2+4 or non-OR–Cu2+ is much lower than those generated by free Cu2+ and the Cu2+-glutamine complex (glutamine is the dominant amino acid in CSF), especially at the beginning of the redox cycle. Although H2O2 as a ROS could also inflict oxidative stress/damage, we note that in vivo H2O2 is readily decomposed by enzymes such as catalase and GSH peroxidase or reacted away with antioxidants such as AA and GSH. Therefore a harmful buildup of H2O2 given rise by the PrP–Cu2+ complexes is unlikely. It was estimated that up to 250 μM H2O2 could be produced within brain neuropil every minute.64 The H2O2 concentration depicted in Figure 5A (sub-μM levels produced by AA at a physiologically relevant concentration at the beginning) is only a small fraction of the known endogenous H2O2 concentration in the CNS. Therefore, the capacity of brain homeostasis of endogenous H2O2 appears to be more than sufficient to reduce any adverse effects that might be caused by H2O2 generated by the PrP–Cu2+ complexes. More importantly, our observation of the in vitro production of H2O2 is supported by the cell culture work conducted by Nishimura et al.65 In their work, the PrP-deficient neurons were found to be more susceptible to Cu2+ toxicity than normal neurons. In addition, in the presence of Cu2+, more intracellular H2O2 was detected in the media of normal neurons and the viability of these neurons is not greatly impacted. This is consistent with the common belief that H2O2 is much less potent than the oxygen-containing radicals (e.g., OH•) and does not readily cause oxidative damage.66–68 In fact, Rice and coworkers did not detect lipid peroxidation in cell membranes when dopaminergic neurons were exposed to high dosage of H2O2.64 Taken together, as summarized in Figure 6, we propose that H2O2 generated at the PrP-residing membrane could act as an important signaling molecule. There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that H2O2 is a signaling messenger capable of modulating synaptic activities and triggering a variety of cellular events.23,67–70 Indeed, Herms et al. have reported that 0.001% exogenous H2O2 enhances inhibitory synaptic activity in wild-type mouse Purkinje cells.71 More relevantly, a prominent mechanism for H2O2-triggered cell signaling involves diffusion of H2O2 from extracellular space to cytosol to enhance protein tyrosine phosphorylation via simultaneous inactivation of tyrosine phosphotases and activation of tyrosine kinases.69 In support of this mechanism, we note that Mouillet-Richard and coworkers suggested a role for PrP in signal transduction that might be facilitated by coupling of the membrane-anchored PrP to the intracellular tyrosine kinase Fyn through an unidentified signaling molecule.72

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the possible roles of PrP–Cu2+ complexes in quenching the Cu2+ redox cycling or gradual production of H2O2 for signal transduction. PrP is tethered to cell membrane via the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor (green) with its α-helices in the C terminus shown in orange, N-linked carbohydrates in purple, and the OR and non-OR domains near the N-terminus depicted in white. When [Cu2+] is at a low level (nM or lower) and at pH ranging between 5.5 and 7.4, Cu2+ (blue sphere) remains bound in the OR–Cu2+ mode (left), quenching the Cu2+ redox cycling. At higher [Cu2+] (μM) and a pH closer to the physiological value, the binding mode transitions to OR–Cu2+4 (right), leading to a gradual and controlled production of H2O2. Coordinates for the PrP C-terminal domain, along with carbohydrates, GPI anchor and membrane were kindly provided by Professor Valerie Daggett (U. Washington).

In conclusion, we demonstrate that the occurrence/inhibition of the redox cycling of Cu2+ by PrP is dependent on binding mode. The voltammetric data, kinetic studies, and H2O2 detection and quantification unequivocally indicate that OR–Cu2+ is the most effective mode in inhibiting the Cu2+ redox cycling and in sequestering uncomplexed Cu2+, thus minimizing possible oxidative damage. Specifically, at nanomolar or lower Cu2+ concentrations, which favor the formation of OR–Cu2+, the complete abolishment of redox cycling of Cu2+ by PrP is realized by shifting the redox potential of the resultant complex out of the range wherein the complexed Cu+ is oxidizable by O2 (Figure 6). As free or weakly complexed Cu2+ concentration increases to micromolar levels, the binding mode transitions to high Cu2+ occupancy, which facilitates the redox cycling of Cu2+ and conversion of O2 to H2O2. Such results challenge the currently held hypothesis that the high occupancy mode quenches Cu2+ redox cycling. We show that both OR–Cu2+4 and non-OR–Cu2+ produce H2O2 in a controlled and gradual manner. Instead of producing a large amount of H2O2 that might inflict cellular damage, H2O2 generated at a lower level probably serves as a cellular signal to initiate important cellular processes. We therefore suggest that OR–Cu2+, OR–Cu2+4 and non-OR–Cu2+ all contribute to the maintenance of neuronal integrity by inhibiting the formation of the radical forms of ROS and regulating the endocytotic processes, perhaps through an H2O2 dependent signaling mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Partial support of this work by the NIH (SC1MS070155-01 to FZ and GM065790 to GM) is gratefully acknowledged. F. Z. also acknowledges support from the NIH-RIMI Program at California State University, Los Angeles (P20-MD001824-01).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Additional experimental details about the electrochemical studies are in the Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Science. 1997;278:245–251. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobb NJ, Surewicz WK. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2574–2585. doi: 10.1021/bi900108v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandner S. Br Med Bull. 2003;66:131–139. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson TM, editor. Parkinson’s Disease. Informa Healthcare USA, Inc; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sisodia SS, Tanzi RE, editors. Alzheimer’s Disease. Springer; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaggelli E, Bernardi F, Molteni E, Pogni R, Valensin D, Valensin G, Remelli M, Luczkowski M, Kozlowski H. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:996–1006. doi: 10.1021/ja045958z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandey KK, Snyder JP, Liotta DC, Musaev DG. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:1127–1135. doi: 10.1021/jp909945e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walter ED, Stevens DJ, Visconte MP, Millhauser GL. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15440–15441. doi: 10.1021/ja077146j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown DR, Qin K, Herms JW, Madlung A, Manson J, Strome R, Fraser PE, Kruck T, von Bohlen A, Schulz-Schaeff W, Giese A, Westaway D, Kretzschmar H. Nature. 1997;390:684–687. doi: 10.1038/37783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaggelli E, Kozlowski H, Valensin D, Valensin G. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1995–2044. doi: 10.1021/cr040410w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millhauser GL. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:79–85. doi: 10.1021/ar0301678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Millhauser GL. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2007;58:299–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh N, Singh A, Das D, Mohan ML. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;12:1271–1294. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vassallo N, Herms J. J Neurochem. 2003;86:538–544. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koppenol WH. Redox Rep. 2001;6:229–234. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barb WG, Baxendale JH, George P, Hargrave KR. Trans Faraday Soc. 1951;47:462–500. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baruch-Suchodolsky R, Fischer B. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4354–4370. doi: 10.1021/bi802361k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:1–85. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86093-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverblatt E, Robinson AL, King CG. J Am Chem Soc. 1943;65:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srogl J, Voltrova S. Org Lett. 2009;11:843–845. doi: 10.1021/ol802715c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strizhak PE, Basylchuk AB, Demjanchyk I, Fecher F, Schneider FW, Münster AF. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2000;2:4721–4727. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001215)39:24<4573::aid-anie4573>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang D, Li X, Liu L, Yagnik GB, Zhou F. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:4896–4903. doi: 10.1021/jp9095375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erecińska M, Silver IA. Respiration Physiology. 2001;128:263–276. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegel GJ, Albers RW, Brady SDP. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular, and Medical Aspects. 7. Academic Press; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chattopadhyay M, Walter ED, Newell DJ, Jackson PJ, Aronoff-Spencer E, Peisach J, Gerfen GJ, Bennett B, Antholine WE, Millhauser GL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12647–12656. doi: 10.1021/ja053254z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walter ED, Chattopadhyay M, Millhauser GL. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13083–13092. doi: 10.1021/bi060948r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burns CS, Aronoff-Spencer E, Legname G, Prusiner SB, Antholine WE, Gerfen GJ, Peisach J, Millhauser GL. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6794–6803. doi: 10.1021/bi027138+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Õsz K, Nagy Z, Pappalardo G, Di Natale G, Sanna D, Micera G, Rizzarelli E, Sóvágó I. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:7129–7143. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hureau C, Charlet L, Dorlet P, Gonnet F, Spadini L, Anxolabéhère-Mallart E, Girerd J-J. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:735–744. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies P, Marken F, Salter S, Brown DR. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2610–2619. doi: 10.1021/bi900170n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens DJ, Walter ED, Rodriguez A, Draper D, Davies P, Brown DR, Millhauser GL. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:11. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miura T, Sasaki S, Toyama A, Takeuchi H. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8712–8720. doi: 10.1021/bi0501784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruiz FH, Silva E, Inestrosa NC. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:491–495. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aronoff-Spencer E, Burns CS, Avdievich NI, Gerfen GJ, Peisach J, Antholine WE, Ball HL, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Millhauser GL. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13760–13771. doi: 10.1021/bi001472t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns CS, Aronoff-Spencer E, Dunham CM, Lario P, Avdievich NI, Antholine WE, Olmstead MM, Vrielink A, Gerfen GJ, Peisach J, Scott WG, Millhauser GL. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3991–4001. doi: 10.1021/bi011922x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonomo RP, Impellizzeri G, Pappalardo G, Rizzarelli E, Tabbì G. Chem Eur J. 2000;6:4195–4201. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20001117)6:22<4195::aid-chem4195>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiraishi N, Ohta Y, Nishikimi M. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. 2000;267:398–402. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Requena JR, Groth D, Legname G, Stadtman ER, Prusiner SB, Levine RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7170–7175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121190898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shearer J, Rosenkoetter KE, Callan PE, Pham C. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:1173–1175. doi: 10.1021/ic102294u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang C, Liu L, Zhang L, Peng Y, Zhou F. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8134–8142. doi: 10.1021/bi1010909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. [accessed July 5, 2010]; http://www.basinc.com/mans/PE-man.pdf.

- 42.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonomo RP, Impellizzeri G, Pappalardo G, Purrello R, Rizzarelli E, Tabbi G. J Chem Soc-Dalton Trans. 1998:3851–3857. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown DR, Wong BS, Hafiz F, Clive C, Haswell SJ, Jones IM. Biochem J. 1999;344:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stańczak P, Kozlowski H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamoto N, Kuwata K. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:1209–1218. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0564-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang D, Men L, Wang J, Zhang Y, Chickenyen S, Wang Y, Zhou F. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9270–9282. doi: 10.1021/bi700508n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson DL, Cox MM, Freeman WH. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. W. H. Freeman; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conway BE. Electrochemical Data. Greenwood Press; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dryhurst G, Kadish KM, Scheller F, Renneberg R. Biological Electrochemistry. Academic Press; New York and London: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deschamps P, Zerrouk N, Nicolis I, Martens T, Curis E, Charlot MF, Girerd JJ, Prange T, Benazeth S, Chaumeil JC, Tomas A. Inorg Chim Acta. 2003;353:22–34. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hureau C, Mathé C, Faller P, Mattioli TA, Dorlet P. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:1055–1064. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sayre LM. Science. 1996;274:1933–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ivanov AI, Parkinson JA, Cossins E, Woodrow J, Sadler PJ. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2000;5:102–109. doi: 10.1007/s007750050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strozyk D, Bush AI. In: Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RKO, editors. John Wiley & Sons; West Sussex: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pall HS, Blake DR, Gutteridge JM, Williams AC, Lunec J, Hall M, Taylor A. Lancet. 1987;2:238–241. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu M, Qin ZJ, Hu DM, Munishkina LA, Fink AL. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8135–8142. doi: 10.1021/bi052584t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Varadarajan S, Yatin S, Aksenova M, Butterfield DA. J Struct Biol. 2000;130:184–208. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith MA, Joseph JA, Perry G. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;924:35–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pauly PC, Harris DA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33107–33110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jovic M, Sharma M, Rahajeng J, Caplan S. Histol Histopath. 2010;25:99–112. doi: 10.14670/hh-25.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luzio JP, Rous BA, Bright NA, Pryor PR, Mullock BM, Piper RC. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1515–1524. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.9.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown DR, Schmidt B, Kretzschmar HA. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1686–1693. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen BT, Avshalumov MV, Rice ME. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2468–2476. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nishimura T, Sakudo A, Nakamura I, Lee DC, Taniuchi Y, Saeki K, Matsumoto Y, Ogawa M, Sakaguchi S, Itohara S, Onodera T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cohen G. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;738:8–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Forman HJ, Maiorino MFU. Biochemistry. 2010;49:935–842. doi: 10.1021/bi9020378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Veal EA, Day AM, Morgan BA. Mol Cell. 2007;26:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rhee SG. Science. 2006;312:1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stone JR, Yang S. Antioxi Redox Signaling. 2006;8:243–270. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Herms J, Tings T, Gall S, Madlung A, Giese A, Siebert H, Schurmann P, Windl O, Brose N, Kretzschmar H. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8866–8875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08866.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mouillet-Richard S, Ermonval M, Chebassier C, Laplanche JL, Lehmann S, Launay JM, Kellermann O. Science. 2000;289:1925–1928. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.