Abstract

Multidrug antibiotic resistance is an increasingly serious public health problem worldwide. Thus, there is a significant and urgent need for the development of new classes of antibiotics that do not induce resistance. To develop such antimicrobial compounds, we must look toward agents with novel mechanisms of action. Membrane permeabilizing antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are good candidates because they act without high specificity toward a protein target, which reduces the likelihood of induced resistance. Understanding the mechanism of membrane permeabilization is crucial for the development of AMPs into useful anti-microbial agents. Various models, some phenomenological and others more quantitative or semi-molecular, have been proposed to explain the action of antimicrobial peptides. While these models explain many aspects of AMP action, none of the models captures all the experimental observations and significant questions remain unanswered. Here we discuss the state of the field and pose some questions that, if answered, could speed the discovery of clinically useful peptide antibiotics.

“It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind.“It’s like a wall”

“It’s like a spear”

“It’s like a snake”

“It’s like a fan”

“It’s like a tree”

“It’s like a rope”And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

all were in the wrong”“The blind men and the elephant”

by John Godfrey Saxe (1816–1887)

INTRODUCTION

The clinical incidence of drug resistant microbes has increased dramatically in recent decades leading to hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations and tens of thousands of deaths annually in the United States, alone(Klein et al., 2007; Pittet et al., 2008; Arias and Murray, 2009). Membrane permeabilizing antimicrobial peptides (AMP) have long been discussed as a possible novel class of antibiotics that could be used against drug resistant microbes(White et al., 1995; Yeaman and Yount, 2003; Yount and Yeaman, 2004; Hancock and Sahl, 2006; Easton et al., 2009; Gardy et al., 2009), but a poor understanding of the fundamental principles of AMP action(Shai, 2002; Rathinakumar and Wimley, 2008; Bechinger, 2009; Rathinakumar et al., 2009; Almeida and Pokorny, 2009) has slowed the development of AMPs into clinically useful drugs. Reminiscent of the old story about the six blind men and the elephant, it sometimes appears that antimicrobial peptide laboratories each see a somewhat different aspect of AMP activity. This lack of a consensus on the mechanism of action and on the structure-function relationships is a bottleneck in novel AMP discovery.

The potential advantages of antimicrobial peptides as antimicrobial drugs are significant(Hancock and Sahl, 2006; Hamill et al., 2008; Easton et al., 2009). They have broad-spectrum activity against many strains of Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria, including drug resistant strains, and they are also active against fungi. Furthermore, their interactions with bacterial components do not involve specific protein binding sites, and thus they do not induce resistance. While the bioavailability of AMPs is reduced by the fact that they cannot be taken orally, potential topical and injected applications are abundant and could support peptide antibiotic drugs, if they were available. Recently, peptide antimicrobial drugs have been tested in trials for applications such as oral candidiasis (thrush)(Demegen Pharmaceuticals, 2010), catheter-associated infections(Melo et al., 2006) and implant surface infections(Kazemzadeh-Narbat et al., 2010). These clinically tested antimicrobial peptide drugs are all derived from natural peptides by what is essentially a trial and error approach. This approach does not resolve a major disadvantage of AMPs: their production cost is high compared to chemical antibiotics. For this reason, there is a critical need to design novel AMPs that are as potent as possible, while being short and compositionally simple. The potential for such rational design is currently limited by our lack of understanding of the detailed mechanism of AMP action.

The activity of AMPs must start at the microbial cytoplasmic membrane, since most AMPs permeabilize microbial membranes. For this reason model membrane systems, such as lipid vesicles, have been used for three decades to explore the structure, function and mechanism of AMPs. Yet, despite a huge amount of work a consensus understanding of AMP action in synthetic bilayers is still lacking. To understand antimicrobial peptide activity, it is essential to understand AMP-induced bilayer destabilization. It is equally important to understand the correlation between AMP mechanisms and activities in synthetic bilayers and in microbial membranes. This knowledge will help identify the minimum requirements for AMP activity and is thus important for the design of potent and less complex, i.e. less expensive, AMPs.

Here we briefly overview current knowledge about antimicrobial peptide mechanism of action and we pose important questions that we believe remain essentially unanswered. The answers to these questions will be crucial for further advancements in the field, and for the development of AMPs into useful drugs.

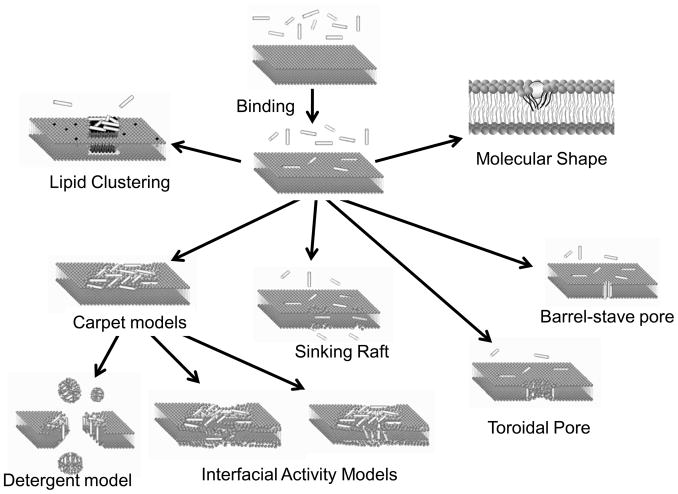

Transmembrane pore models of AMP membrane activity

The simplest models of membrane permeation by peptides involve the formation of membrane-spanning pores (See Figure 1). In the barrel stave pore model(Rapaport and Shai, 1991), peptides interact laterally with one another to form a specific structure enclosing a water-filled channel, much like a protein ion channel. In the toroidal pore model(Ludtke et al., 1996), specific peptide-peptide interactions are not present, but instead peptides affect the local curvature of the membrane cooperatively such that a peptide-lipid toroid of high curvature forms. Alamethicin, a 20 residue pore-forming peptide from the fungus trichoderme viridians, forms membrane spanning pores, at least under some conditions(Huang et al., 2004; Qian et al., 2008). However, depending on hydration and peptide concentration, alamethicin can also exist mainly parallel to the bilayer surface(He et al., 1996). The lytic toxin melittin from honey bee venom is another classical example of a pore forming peptide which forms a membrane spanning pore (Matsuzaki et al., 1997; Sengupta et al., 2008). But in the realm of membrane-active peptides, these classical pore forming toxins may be the exceptions. There are more than 1000 known antimicrobial peptides(Brahmachary et al., 2004; Wang and Wang, 2004; Fjell et al., 2007) and for the majority of them, there is little or no evidence for transmembrane pores(Wimley, 2010). Instead, there is compelling evidence that many AMPs function by binding to membrane surfaces and disrupting the packing and organization of the lipids in a non-specific way, as we discuss next.

Figure 1.

Overview of some popular models of AMP activity, discussed in the literature. While many experimental observations are well described by one or more of these models, none of the models describes all experimental observations. These images are cartoons only, based on our simplistic interpretations of the models.

Non-pore models of AMP activity

In addition to the pore models described above, AMP activity has also been described using non-pore models to explain or categorize the mechanism of AMPs in lipid vesicles (See Figure 1). The carpet model, originally described by Shai(Gazit et al., 1996) is the most commonly cited model of membrane destabilization by AMPs. In the carpet model, antimicrobial peptides accumulate on the membrane surface with an orientation that is parallel to the membrane. When peptide concentration has reached a critical concentration, (i.e. a peptide-rich “carpet” has formed on the membrane surface) permeabilization occurs via global bilayer destabilization. The detergent model is also often cited to explain the catastrophic collapse of membrane integrity, observed with some AMPs at high peptide concentration(Ostolaza et al., 1993; Hristova et al., 1997; Bechinger and Lohner, 2006). Some authors combine the carpet and detergent models into a single idea in which the catastrophic collapse of membrane integrity includes membrane fragmentation. Others distinguish between the two models based on whether or not the peptide-induced leakage efficiency depends on the size of the entrapped solutes(Ostolaza et al., 1993).

Bechinger and Lohner(Bechinger and Lohner, 2006; Bechinger, 2009) recently discussed molecular shape models in which AMP/lipid interactions could be depicted with phase diagrams to describe the propensity of an AMP to permeabilize a membrane by disrupting the lipid packing. Epand and colleagues have proposed a lipid clustering model in which AMPs induce clustering or phase separation of lipids, with leakage occurring due to boundary defects(Epand and Epand, 2009; Epand et al., 2010). Almeida and colleagues have described AMP activity in terms of binding, insertion and perturbation using the sinking raft model which they recently augmented by adding a formal thermodynamic analysis to predict activity(Pokorny and Almeida, 2004; Pokorny et al., 2008; Gregory et al., 2008; Gregory et al., 2009; Almeida and Pokorny, 2009). We have suggested that the physical-chemical concepts in the interfacial activity model might also be useful to explain, predict or engineer the activity of AMPs(Rathinakumar and Wimley, 2008; Rathinakumar et al., 2009; Rathinakumar and Wimley, 2010; Wimley, 2010). Interfacial activity is defined as the propensity of an imperfectly amphipathic peptide to partition into the bilayer interface and drive the vertical rearrangement of the lipid polar and nonpolar groups. The disruption of the normally strict segregation of polar and nonpolar groups causes membrane permeabilization.

While these models, and others, have been useful in discussing AMPs, the molecular organization of the lipid bilayer undergoing leakage of solutes in the presence of AMPs is still very much unknown. Without this knowledge, it remains challenging to predict structure-sequence-activity relationships, and thus it also remains challenging to engineering or design novel AMPs.

Synthetic vesicles as models for living microbes

Based on direct evidence and on the fact that AMPs permeabilize synthetic vesicles with lipid compositions that are similar to bacterial membranes, it has long been believed that AMPs act by compromising microbial membrane integrity(Steiner et al., 1981; Merrifield et al., 1982; Westerhoff et al., 1989). AMPs may induce a large-scale membrane failure, or small defects that dissipate the transmembrane potential. In either case, the expected result would be cell death. Thus, antimicrobial activity and lipid bilayer permeabilization are undoubtedly correlated. Yet, questions remain about how closely the molecular mechanism of vesicle leakage is related to the mechanism of microbial membrane permeabilization, and about whether the membrane is the only biological target of AMPs.

One reason to question the direct correlation between synthetic bilayer permeabilization and microbial sterilization is that the experimental conditions in the two experiments are very different. As discussed in detail elsewhere(Wimley, 2010) and shown in Table 1, the peptide-to-lipid ratio in a typical microbial sterilization assay is 200–1000. This constitutes a massive excess of peptide over membrane compared to a typical vesicle leakage assay where the peptide to lipid ratio is ~0.01. Thus, there are four or five orders of magnitude difference in peptide to lipid ratio between the model system and the bacterial sterilization experiments. It has been shown that much of the peptide in a sterilization assay, under the conditions in Table 1, is actually bound to the microbes(Wimley, 2010). Thus, bacterial sterilization assays are conducted under conditions where the cells are completely saturated with peptide. Peptides are certainly bound to the bacterial membranes, but to account for the massive amount of bound peptide they must also be interacting with other cell components such as lipopolysaccharides, cell wall components, DNA, and perhaps other intracellular macromolecules. It can be estimated that at least 10 to 100 peptides need to be bound to a cell for every lipid molecule in order to observe antimicrobial activity in a microbe sterilization experiment(Wimley, 2010). Under these conditions, with AMPs saturating the microbe, the molecular events occurring at the membrane are unknown. The tools of biophysics have rarely been applied to microbial membrane permeabilization, and thus critical information about these events is missing. Yet, the available results strongly suggest that AMPs do not attack microbial membranes with high efficiency(Rathinakumar et al., 2009; Rathinakumar and Wimley, 2010). This observation raises questions whether the primary action of all AMPs is indeed to compromise the bacterial membrane, and whether or not there might be additional biological targets.

Table 1.

Overview of experimental conditions for vesicle leakage, microbial sterilization, and hemolysis. The vesicle leakage experiments are performed at much lower peptide-to-lipid ratios than the biological assays, impeding direct comparisons.

| Large Unilamellar Vesicle | Bacteria |

|---|---|

| Diameter= 0.1 μm | Diameter= 1.0 μm |

| Vesicles/ml = 2×1012 | Cells/ml = 1×105 |

| Lipids/vesicle = 1×105 | Lipids/cell = 2×107 |

| Lipid conc. = 5×10−4 M | Lipid conc. = 2×10−9 M |

| Peptide conc. = 5×10−6 M | Peptide conc. = 5×10−6 M |

| Peptide/Lipid= 0.01 | Peptide/Lipid= 1000 |

|

| |

| Fungus Cell | Red Blood Cell |

| Diameter= 5 μm | Diameter= 10 μm |

| Cells/ml = 1×105 | Cells/ml = 1×108 |

| Lipids/cell = 1×108 | Lipids/cell = 1×109 |

| Lipid conc. = 2×10−8 M | Lipid conc. = 1×10−5 M |

| Peptide conc. = 5×10−6 M | Peptide conc. = 5×10−6 M |

| Peptide/Lipid= 200 | Peptide/Lipid= 0.5 |

Unanswered questions: Lipid vesicle model systems

Many experimental observations in model systems can be rationalized by one or more of the membrane permeabilization models above. For example, many experiments show that AMPs need to reach a threshold peptide concentration before leakage occurs. Most of the non-pore models involve a collection of peptides working together to destabilize the bilayer, consistent with the experiments. Other experimental observations, however, are more difficult to rationalize, and a mechanistic understanding of the leakage-inducing events at the membrane is lacking. Below we list a set of fundamental questions which remain unanswered for model systems in the field, impeding further progress.

1) How many fundamentally different mechanisms exist?

AMPs have been studied in model systems using an immense variety of techniques, including structural techniques (e.g. circular dichroism, fluorescence, infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, differential scanning calorimetry, isothermal titration calorimetry, atomic force microscopy) and also including functional techniques (e.g. dye release, vesicle swelling, electrophysiology). Based on these experiments, the various overlapping models, described above, and others not described here, have been put forward to describe particular sets of observations. Often, different laboratories propose different models for the behavior of the very same AMP. Like the six blind men describing an elephant, these different studies give very different “views” of the mechanism of AMP permeabilization of membranes. A significant question remains whether there is, fundamentally, a single mechanism of action (the elephant!), or whether there are multiple distinct mechanisms. It remains possible, but unproven, that there is one fundamental mode of action for all AMPs, and that our experimental observations capture different manifestations of this one mechanism under specific conditions. If this is the case, then this one grand mechanism still eludes us. If this is not the case, we have yet to develop the analytical tools to reliably distinguish between the different mechanisms.

2) What is the mechanism of partial transient release?

When antimicrobial peptides are added to lipid vesicles containing entrapped contents, leakage often occurs in the form of a rapid burst over the course of a few minutes, followed by a rapid decrease/cessation of leakage(Wimley, 2010). Frequently, leakage stops completely before all contents have been released. A second addition of peptide causes a new burst of leakage. This enigmatic aspect of AMP activity, partial transient leakage, is commonly observed, but is especially difficult to rationalize within the context of existing models without invoking additional ad hoc events, such as trans-bilayer disequilibrium. A model that provides an experimentally supported mechanistic explanation of partial transient release would go a long way toward revealing AMP mechanism of action in bilayers.

3) What are the mechanisms behind all-or-none and graded leakage?

AMP-induced partial leakage from vesicles can be either all-or-none, in which only a fraction of the vesicles release all of their contents; or it can be graded, in which all of the vesicles release only a fraction of their contents. Most authors assume that the two types of release represent distinct mechanisms. However it remains possible that these are simply two manifestations of the same mechanism of action. In any case, there is no satisfying mechanistic explanation as to how an AMP can give rise to one or the other type of release, especially within the context of partial, transient leakage. For either mechanism, there must be early events that lead to leakage (either all-or-none or graded) immediately after addition of peptide, and these leakage events must be followed by a rearrangement of the system that stops or slows additional leakage. The field desperately needs an experimentally supported model that explains all-or-none and graded partial transient release in terms of specific molecular events.

4) Is there a fundamental difference between size-dependent and size-independent release?

As in the case of graded versus all-or-none release, some experimental observations show vesicle leakage that is independent of entrapped solute size(Ostolaza et al., 1993; Hristova et al., 1997), while others show probe size selectivity(Ladokhin et al., 1997), leading some researchers to propose a “detergent like” catastrophic membrane collapse in the former case and a transmembrane pore in the latter case. It is not yet known whether these are really two distinct mechanisms, or whether size independent and size dependent leakage are two different manifestations of the same basic mechanism of action.

5) Do AMPs translocate across bilayers?

Information on AMP translocation is mostly missing from our understanding of AMP activity in lipid bilayers. It has been hypothesized that the coupled translocation of lipids, peptides and polar solutes is the cause of leakage(Wimley, 2010) but this has not been tested. It remains possible that AMPs act only on bilayer surfaces, inducing changes in lipid packing, changes in lateral lipid organization or changes in local curvature that lead to leakage without peptide translocation. It is also possible that translocation is incidental to leakage, but not an important part of the mechanism. In terms of understanding the physical chemistry of AMP-membrane interactions, it is essential to know whether or not AMPs must translocate through the membrane to be active.

6) Can the physical-chemical basis for activity be parameterized or predicted?

A void in the AMP research literature is the lack of explicit, molecular, structure-function relationships. In part, this is the reason why the many different models of AMP activity are mostly descriptive, and lack quantitative predictive power. Without a quantitative parameterization of the important factors that determine and regulate AMP activity, rational AMP design and engineering will remain difficult.

Unanswered questions: Living microbes

There are also open questions that pertain to the sterilizing activity of AMPs against microbes.

1) How many fundamentally different mechanisms exist?

By definition, AMPs are peptides that kill microbes, and there is good evidence that the membrane-disrupting properties of AMPs are involved in biological activity. However, as in the case of lipid vesicle permeabilization, we do not know if there is a single common mechanism for bioactivity, or if multiple distinct mechanisms exist. Unfortunately, there are few biophysical or physical chemical experiments which address what happens at the bacterial membrane when AMPs are present. Thus, the answer to this critical question remains elusive.

2) How are vesicle leakage and microbial killing correlated?

It is well known that there is overlap between vesicle leakage and microbe sterilization: antimicrobial peptides usually cause leakage in vesicles, and peptides that cause leakage in vesicles often have antimicrobial activity(Rathinakumar and Wimley, 2010). However, the quantitative correlation between the potency of the antimicrobial activity and the degree of vesicle leakage induced by a particular peptide is unknown. Similarly, the overlap in molecular mechanism between microbial sterilization and vesicle permeabilization is unknown. It remains possible that the molecular mechanisms of leakage are different and that we observe overlap between the two types of systems because they are driven by similar physical chemical interactions. To begin understanding this correlation, first we need to characterize the AMPs in the act of killing microbes with the tools of biophysics and physical chemistry. How well are they bound to the bacterial membrane, and what is their bound conformation? How do the physical properties of the bacterial lipids and bacterial membrane change in response to AMPs? While many studies have addressed the interactions between AMPs and synthetic lipid bilayers, there is a lack of mechanistic information about the interactions of AMPs with bacterial membranes. Systematic studies of leakage-inducing and sterilizing activities, as well as cross-characterization of potent antimicrobial and membrane destabilizing sequences are rare in the literature. We believe that such detailed studies are desperately needed for a better understanding of the physical-chemistry determinants of biological activity.

3) Is membrane binding the sole basis for selectivity?

AMPs disrupt bacterial membranes, but leave mammalian membranes intact at the same total peptide concentration. It has been proposed that the reason for this selectivity is simply the different binding affinities of AMPs to the different types of membranes. The affinity of AMPs for mammalian membranes is expected to be lower than their affinities for bacterial membranes, because of differences in lipid composition(White et al., 1995; Hristova et al., 1997; Yount and Yeaman, 2004). However, binding affinities of AMPs to mammalian or bacterial membranes have almost never been measured directly. A testable scenario for the specificity of AMPs, is as follows: (i) At identical bound concentrations (number of bound peptides per lipid), AMPs behave the same in all membranes. Thus, at a high enough bound peptide concentration, AMPs will disrupt the integrity of any membrane. (ii) AMPs are selective for microbes because they bind better to microbial membranes. To our knowledge, there are no experiments that address the effects of AMPs on microbes and mammalian cells at the same bound peptide concentrations. In fact, bacterial sterilization assays are usually performed at much higher peptide to lipid ratios than mammalian cell lysis assays (Table 1). Alternately, bacterial and eukaryotic membranes might have different inherent susceptibilities to AMPs based on lipid physical chemistry or membrane material properties. Despite three decades of work on AMPs, these ideas remain essentially untested in cells.

4) What is the lethal activity?

The activity of an AMP that is lethal to microbes is far from certain. Most AMPs cause leakage of small ions, and some also cause leakage of larger molecules and even large-scale membrane disruption. It is possible that leakage of H+, Na+ and K+ alone, by dissipating the transmembrane potential, could lead to cell death by depletion of ATP. A second possibility is that an increase in selective water permeability could lead to osmotic lysis of cells. A third alternative is that AMPs kill cells only when they physically destroy the membrane structure, releasing metabolites and proteins. Yet, others have suggested that AMPs could kill microbes by binding to intracellular targets such as DNA and chaperonins(Cudic and Otvos, Jr., 2002; Hong et al., 2003; Otvos, Jr., 2005; Otvos, Jr. et al., 2006). The fact that these ideas are not mutually exclusive complicates the search for an answer to this question. Despite a lot of work in the field, we are still not certain what aspect, or aspects, of AMP-microbe interactions are actually lethal to the cell. Without this knowledge, we are handicapped in our attempts to engineer or design novel AMPs.

5) Is membrane translocation required for activity?

While most AMPs permeabilize membranes, it is not known whether membrane permeabilization is coupled to peptide translocation or whether peptide translocation is required for biological activity. Based on the massive amount of AMPs bound to a microbial membrane under typical sterilization conditions (Table 1) it is possible that AMPs could sterilize microbes due to the coupled membrane translocation of AMPs and polar solutes(Wimley, 2010). Currently, there are no reliable assays for peptide translocation across synthetic or biological membranes. We hope that such assays are developed soon, and that they are applied to both lipid vesicle systems and microbial membranes. Until we have the results of such translocation experiments, it will be difficult to specify a molecular mechanism of AMP action.

Future prospects

For three decades the prospects for antimicrobial peptides as an alternate class of antibiotics have seemed good. Yet, there have been a few actual success stories. We believe that a major bottleneck in the development of new antimicrobial peptide drugs arises from our inability to describe their mechanism of action in physical-chemical terms that are useful for future design and engineering applications. Perhaps we are like the six blind men, each accurately describing the one particular aspect of activity that he observes with his favorite research tools, while missing the big picture (the elephant). Here, we have discussed some of the open questions in the field of antimicrobial peptides. Answers to these questions will help move the field further along the “pipeline” towards development of AMPs as clinically useful drugs.

Acknowledgments

Supported by GM060000 and GM068619. We dedicate this review to our advisor Stephen H. White, in whose laboratory we completed our first AMP research projects.

Reference List

- Almeida PF, Pokorny A. Mechanisms of antimicrobial, cytolytic, and cell-penetrating peptides: from kinetics to thermodynamics. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8083–8093. doi: 10.1021/bi900914g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias CA, Murray BE. Antibiotic-resistant bugs in the 21st century--a clinical super-challenge. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:439–443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0804651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechinger B. Rationalizing the membrane interactions of cationic amphipathic antimicrobial peptides by their molecular shape. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 2009;14:349–355. [Google Scholar]

- Bechinger B, Lohner K. Detergent-like actions of linear amphipathic cationic antimicrobial peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1529–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahmachary M, et al. ANTIMIC: a database of antimicrobial sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D586-9, D586–D589. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudic M, Otvos L., Jr Intracellular targets of antibacterial peptides. Curr Drug Targets. 2002;3:101–106. doi: 10.2174/1389450024605445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demegen Pharmaceuticals. Demegen Pharmaceticals Candidiasis Wedsite. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Easton DM, et al. Potential of immunomodulatory host defense peptides as novel anti-infectives. Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand RF, et al. Probing the “charge cluster mechanism” in amphipathic helical cationic antimicrobial peptides. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4076–4084. doi: 10.1021/bi100378m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epand RM, Epand RF. Lipid domains in bacterial membranes and the action of antimicrobial agents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjell CD, Hancock RE, Cherkasov A. AMPer: a database and an automated discovery tool for antimicrobial peptides. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1148–1155. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardy JL, et al. Enabling a systems biology approach to immunology: focus on innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazit E, et al. Structure and orientation of the mammalian antibacterial peptide cecropin P1 within phospholipid membranes. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:860–870. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory SM, et al. A quantitative model for the all-or-none permeabilization of phospholipid vesicles by the antimicrobial peptide cecropin A. Biophys J. 2008;94:1667–1680. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.118760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory SM, Pokorny A, Almeida PF. Magainin 2 Revisited: A Test of the Quantitative Model for the All-or-None Permeabilization of Phospholipid Vesicles. Biophys J. 2009;96:116–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill P, et al. Novel anti-infectives: is host defence the answer? Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock RE, Sahl HG. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1551–1557. doi: 10.1038/nbt1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He K, et al. Mechanism of alamethicin insertion into lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 1996;71:2669–2679. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79458-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong RW, et al. Transcriptional profile of the Escherichia coli response to the antimicrobial insect peptide cecropin A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.1-6.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristova K, Selsted ME, White SH. Critical role of lipid composition in membrane permeabilization by rabbit neutrophil defensins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24224–24233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HW, Chen FY, Lee MT. Molecular mechanism of Peptide-induced pores in membranes. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;92:198304. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.198304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemzadeh-Narbat M, et al. Antimicrobial peptides on calcium phosphate-coated titanium for the prevention of implant-associated infections. Biomaterials. 2010;31:9519–9526. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein E, Smith DL, Laxminarayan R. Hospitalizations and deaths caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, United States, 1999–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1840–1846. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.070629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladokhin AS, Selsted ME, White SH. Sizing membrane pores in lipid vesicles by leakage of co-encapsulated markers: Pore formation by melittin. Biophys J. 1997;72:1762–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78822-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke SJ, et al. Membrane pores induced by magainin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13723–13728. doi: 10.1021/bi9620621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki K, Yoneyama S, Miyajima K. Pore formation and translocation of melittin. Biophys J. 1997;73:831–838. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78115-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo MN, Dugourd D, Castanho MA. Omiganan pentahydrochloride in the front line of clinical applications of antimicrobial peptides. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2006;1:201–207. doi: 10.2174/157489106777452638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield RB, Vizioli LD, Boman HG. Synthesis of the antibacterial peptide cecropin A (1–33) Biochemistry. 1982;21:5020–5031. doi: 10.1021/bi00263a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostolaza H, et al. Release of lipid vesicle contents by the bacterial protein toxin a-haemolysin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1147:81–88. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90318-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otvos L., Jr Antibacterial peptides and proteins with multiple cellular targets. J Pept Sci. 2005;11:697–706. doi: 10.1002/psc.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otvos L, Jr, et al. Prior antibacterial peptide-mediated inhibition of protein folding in bacteria mutes resistance enzymes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:3146–3149. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00205-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittet D, et al. Infection control as a major World Health Organization priority for developing countries. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68:285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny A, Almeida PF. Kinetics of dye efflux and lipid flip-flop induced by delta-lysin in phosphatidylcholine vesicles and the mechanism of graded release by amphipathic, alpha-helical peptides. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8846–8857. doi: 10.1021/bi0497087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny A, et al. The activity of the amphipathic peptide delta-lysin correlates with phospholipid acyl chain structure and bilayer elastic properties. Biophys J. 2008;95:4748–4755. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.138701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian S, et al. Structure of the Alamethicin Pore Reconstructed by X-ray Diffraction Analysis. Biophys J. 2008;94:3512–3522. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.126474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport D, Shai Y. Interaction of fluorescently labeled pardaxin and its analogues with lipid bilayers. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23769–23775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinakumar R, Walkenhorst WF, Wimley WC. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial peptides by rational combinatorial design and high-throughput screening: The importance of interfacial activity. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7609–7617. doi: 10.1021/ja8093247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinakumar R, Wimley WC. Biomolecular engineering by combinatorial design and high-throughput screening: small, soluble peptides that permeabilize membranes. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9849–9858. doi: 10.1021/ja8017863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinakumar R, Wimley WC. High-throughput discovery of broad-spectrum peptide antibiotics. FASEB J. 2010;24:3232–3238. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-157040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta D, et al. Toroidal pores formed by antimicrobial peptides show significant disorder. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:2308–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shai Y. Mode of action of membrane active antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 2002;66:236–248. doi: 10.1002/bip.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, et al. Sequence and specificity of two antibacterial proteins involved in insect immunity. Nature (London) 1981;292:246–248. doi: 10.1038/292246a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wang G. APD: the Antimicrobial Peptide Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:590–592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhoff HV, et al. Magainins and the disruption of membrane-linked free-energy transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:6597–6601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SH, Wimley WC, Selsted ME. Structure, function, and membrane integration of defensins. Cur Opinion Struc Biol. 1995;5:521–527. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimley WC. Describing the mechanism of antimicrobial Peptide action with the interfacial activity model. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:905–917. doi: 10.1021/cb1001558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeaman MR, Yount NY. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:27–55. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yount NY, Yeaman MR. Multidimensional signatures in antimicrobial peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:7363–7368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401567101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]