Abstract

Changes in cellular and synaptic plasticity related to learning and memory are accompanied by both up-regulation and down-regulation of the expression levels of proteins. Both de novo protein synthesis and post-translational modification of existing proteins have been proposed to support the induction and maintenance of memory underlying learning. However, little is known regarding the identity of proteins regulated by learning that are associated with the early stages supporting the formation of memory over-time. In this study we have examined changes in protein abundance at two different times following one-trial in vitro conditioning of Hermissenda using two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE), quantification of differences in protein abundance between conditioned and unpaired controls, and protein identification with tandem mass spectrometry. Significant regulation of protein abundance following one-trial in vitro conditioning was detected 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning. Proteins were identified that exhibited statistically significant increased or decreased abundance at both 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning. Proteins were also identified that exhibited a significant increase in abundance only at 30 min, or only at 3 hr post-conditioning. A few proteins were identified that expressed a significant decrease in abundance detected at both 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning, or a significant decrease in abundance only at 3 hr post-conditioning. The proteomic analysis indicates that proteins involved in diverse cellular functions such as translational regulation, cell signaling, cytoskeletal regulation, metabolic activity, and protein degradation contribute to the formation of memory produced by one-trial in vitro conditioning. These findings support the view that changes in protein abundance over-time following one-trial in vitro conditioning involve dynamic and complex interactions of the proteome.

Keywords: Proteomics, difference gel electrophoresis, Hermissenda, cytoskeletal proteins, Pavlovian conditioning, memory formation

It is widely accepted that the development of persistent memory occurs in distinct stages or phases that have different underlying mechanisms (Freidler and Allweis 1978; Ng and Gibbs 1991; Rosenzweig et al. 1993; Squire et al. 1993; DeZazzo and Tully 1995; McGaugh 2000; Kandel 2001; Dudai 2002). Examination of the formation of memory over-time suggests that the different stages can be differentiated based upon the contribution of signaling pathways, post-translational modifications, protein synthesis, and gene induction (Otani et al, 1989; Ng and Gibbs 1991; Crow and Forrester 1993; Fazoli et al. 1993; Rosenzweig et al. 1993; Yin et al. 1994; DeZazzo and Tully 1995; Freeman et al. 1995; Nguyen and Kandel 1997; Kang and Schuman 1996; Roberts et al. 1998; Bradshaw et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2005). The time-dependent development of cellular and synaptic modifications proposed to underlie the formation of memory in diverse species also exhibit discontinuous stages (e.g. Barzilai et al. 1989; Otani et al. 1989; Huang et al. 1994; Ghirardi et al. 1995; Frey et al. 1996; Schilhab et al. 1996; Winder et al. 1998; Xia et al. 1998; Parker et al. 1999; Bailey et al. 1999; Crow et al.1999; Sutton et al. 2004).

The number of stages, temporal characteristics of the different stages and their mechanistic complexity supporting memory formation may depend upon the species, learning paradigm, and other experimental variables; however several generalizations can be applied to most studies examining this complex process. It has been proposed that three mechanistically distinct stages may support most examples of long-term memory formation (for reviews see Hawkins and Kandel 2006; Cobb and Pitt 2008). An early stage, dependent upon post-translational modification of existing proteins, an intermediate stage that is dependent upon translation but not transcription, and a third stage dependent upon both protein synthesis and gene transcription. These stages have been observed in studies of many diverse species and different models of cellular and synaptic plasticity, although the contribution of de novo protein synthesis continues to be investigated (see recent discussions by Gold 2008; Rudy 2008; Routtenberg 2008; Alberini 2008; Klann and Sweat 2008; Hernandez and Abel 2008).

There is an extensive body of data collected from different species indicating that the formation of long-term memory is related to changes in the expression of proteins. However little is known about the identity of specific proteins or the potential contribution of multiple protein complexes whose upregulation or downregulation may support changes in cellular and synaptic plasticity associated with memory formation. Recent studies have begun to apply proteomic profiling of cellular proteins using conventional 2D gel electrophoresis or difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE) and mass spectrometry (MS) in analyses of learning and plasticity to address these experimental issues (e.g. McNair et al. 2006; Piccoli et al. 2007; Henniger et al. 2007; Pinaud et al. 2008; Jüch et al. 2009).

Here we report on the examination of time-dependent changes in the Hermissenda proteome regulated by one-trial in vitro conditioning. Using established DIGE based procedures (Ünlü et al. 1997; Viswanathan et al. 2006), protein spots whose abundance was significantly modified by conditioning were extracted from 2D gels and identified by MS/MS analysis. The identified proteins that are upregulated or downregulated by in vitro conditioning represent a diverse classification of functions that may contribute to the early events supporting associative memory formation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

One-trial in vitro conditioning

The one-trial in vitro conditioning procedure is derivative of the one-trial conditioning procedure reported by Crow and Forrester (1986). Light (CS) paired with the application of 5-HT to the exposed, but otherwise intact nervous system of Hermissenda produces a significant CS elicited inhibition of locomotion when animals are tested 24 hrs post-conditioning. Unpaired and backward control groups are significantly different from conditioned animals. One-trial in vitro conditioning consists of pairing the CS (Light) with the application of 5-HT to the isolated nervous system. In vitro conditioning has been shown to produce multiple stages of time-dependent enhanced excitability in sensory neurons (photoreceptors), synaptic facilitation of the monosynaptic connection between sensory neurons and interneurons, and changes in protein phosphorylation (Crow & Forrester 1991,1993; Crow & Siddiqi 1997; Crow & Xue-Bian 2000, 2002, 2007, 2010; Crow et al. 1996,1997,1998,1999, 2003; Yamoah et al. 2005; Redell et al. 2007).

The nervous systems were dissected following established procedures (Crow et al. 1996) and placed into centrifuge tubes containing ASW. The ASW temperature was maintained at 15° C. The isolated nervous systems (n=7) were dark-adapted for 12 min followed by one-trial of light (CS) (~10−4 W/cm2) paired with the application of 5-HT (final concentration 0.1 mM). The CS and 5-HT were applied for 5 min followed by an ASW rinse under red light. Unpaired control groups received the 5 min CS followed by 5 min in the dark before the application of 5-HT. The 5-HT was applied in the dark (red light) for the unpaired controls and remained in the ASW for 5 min followed by an ASW rinse. The isolated nervous systems were lysed at different times following conditioning and control procedures (30 min, 3 hr) and incubated in the Cy dyes. Each post-conditioning time had a corresponding unpaired control group for comparison.

CyDye labeling

To minimize potential animal-to-animal variability protein samples were prepared by pooling seven nervous systems from the in vitro conditioned group or seven nervous systems from the unpaired control group for each time point with six independent replications. Experimental and control samples were lysed using a pellet mixer for 1 min, and vortexed for 30 sec in a 45µl solution containing 9.2 M urea, 2% IGEPAL CA-360, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 2% carrier ampholytes, 100 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovandate, and 0.1 mM okadiac acid. The pH of the lysis and sample buffers was adjusted to 8.5 with NaOH. For some experiments the reductant and ampholytes were omitted from the lysis buffer and added to the sample buffer after CyDye labeling. The lysates were centrifuged at 13 600g for 20 min at 4 °C. Protein content in the supernatant was determined by a 5 µl sample collected for Bradford assays (Bradford, 1976). The stock solution of each dye was prepared by adding 5 µl of fresh DMF to 5 nmol of the CyDye powder. Working solutions consisted of diluting 1 µl of the stock solution with 1 µl of DMF for labeling. Approximately 50 µg of protein was labeled with 600 pmol of either Cy2, Cy3, or Cy5 following the manufacturer’s protocol (GE Healthcare). Prior to the first dimension 40 µl supernants were added to 80 µl of sample buffer containing 9 M Urea, 2% dithiothreitol (DTT), .8% carrier ampholytes, and 2% IGEPAL CA-630.

The internal standard procedure described by Alban et al. (2003) was used with the DIGE experiments. Equal volumes of each of the experimental and control samples at the different time points were pooled and labeled with Cy2 to generate an internal standard sample. Lysates taken from each sample at each time point consisting of the upaired control and in vitro conditioned group lysed at 30 min, and upaired control and in vitro conditioned group lysed at 3 hr and the internal standard were labeled with 1µl Cy3, Cy5, or Cy2. Dye labeling consisted of incubations for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. The labeling reaction was stopped with the addition of 1 µl of quenching solution (5 M Methylamine-HCl, 10 mM HEPES, pH 8.0) added to each sample for 15 min at 4°C in the dark. The samples were then combined in pairs along with the internal standard sample as described. For some experiments we employed reverse or reciprocal labeling where two gels were run for each time point comparison in which the order of labeling was reversed. Blind experimental procedures were used for Cy dye labeling, gel imaging and data analysis.

Difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE)

CyDye labeled Proteins in lysate samples were resolved by 2DE using a first-dimension isoelectric focusing (IEF) gel with an immobilized pH gradient (4–7) and a precast SDS polyacrylamide (8–18% linear gradient) second-dimension gel. IEF strips were rehydrated in DeStreak rehydration solution and IPG buffer containing carrier ampholytes. Equilibration of IEF strips for the second dimension involved a two-step procedure with two buffer solutions. The stock equilibration solution contained 50 mM Tris (pH 8.8), 6 M Urea, 30% Glycerol, 2% SDS, and .002% Bromophenol Blue. Equilibration buffer solution 1 consisted of 0.2g DTT in 20ml of the stock solution (Final concentration 1%). Equilibration solution II consisted of 0.5g iodoacetamide in 20 ml of the stock solution (Final concentration 2.5%). Images of Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5 labeled proteins of each gel were obtained immediately after completion of the second dimension using a Typhoon 9400 scanner (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) with excitation/emission wavelengths of 488/520 nm for Cy2, 532/580 nm for Cy3 and 633/670 nm for Cy5. After imaging the gels were stained with Coomassie blue for spot extraction and MS/MS analysis.

DIGE analysis

2D DIGE gels were analyzed with both ImageMaster software (GE Healthcare) and a manually generated template generated from a master gel to identify CyDye labeled proteins expressing different abundance levels. Comparisons were examined within-gels involving in vitro conditioned and unpaired controls and between gels for differences between conditioned and controls at different time points. Spot volumes were normalized to compensate for differences in system gain since the overall fluorescence ratio between the dye-labeled proteins is not unity due to the different extinction coefficients of Cy3 and Cy5, variation in sample labeling and loading, different laser intensity, and different filter transmittance. A normalization value (system gain) was computed based upon the average intensity of a group of ten protein spots selected from constant regions of the gels. Following gain adjustments and log transformations the ratios between conditioned and controls were analyzed as standard scores (z-scores) with ratios greater or less than z-scores of ±1.96 from the mean determining statistical significance (p<.05). Overall differences in spot volume between the conditioned groups and unpaired controls for each time-point were established using a two-way ANOVA. Proteins exhibiting statistically significant changes in abundance were excised from Coomassie blue stained gels for identification by MS/MS.

In-gel digestion and mass spectrometry

Coomassie stained gel spots were rinsed in water for 10 min, dehydrated with 0.2 M NH4HCO3/50% acetonitrile for ~30 min and dried completely in a Speed-Vac. The gel spots were then rehydrated in 50mM NH4HCO3 containing 0.5 –1mg modified trypsin (Promega) and digested for 20hr at 37° C. The supernatant was removed to a clean microfuge tube, the gel fragments extracted with aqueous 50% methanol/2% formic acid for ~30 min and combined with the initial extract. This was evaporated to ~30 µl, acidified with formic acid to ~ pH 3 and desalted on a C18 ZipTip (Millipore) as recommended by the vendor. Peptides were eluted from the ZipTip with 3–6 µl of an aqueous solution of 50% methanol and 2% formic acid. One µl was spotted on a MALDI target plate, dried and matrix (alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) spotted and dried, followed by analysis in reflector mode on an ABI/SCIEX 4700 Proteomics Analyzer TOF/TOF mass spectrometer. Detected monoisotopic peptide masses were analyzed using MS-Fit (Protein Prospector, University of California, San Francisco), ProFound (PROWL, Rockefeller University) or the system’s GPS Explorer software interfaced with the Mascot database for protein database searches and protein identification by peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF). For the majority of the samples there were no good matches or identification by PMF since the Hermissenda genome has not been sequenced. When PMF results were not straightforward, selected peptide precursor ions were subjected to high-energy collision induced dissociation to generate MS/MS fragment ions that were analyzed by the above search engines and confirmed by visual inspection to deduce amino acid sequences of the peptides providing confirmation of the identity of the proteins. To reduce the ambiguity involved with identification, proteins verified by NCBI BLAST searches had expectation values of <.01 (Flensburg and Liminga, 2005).

RESULTS

Proteins regulated by one-trial in vitro conditioning

The time-dependent regulation of the proteome following one-trial in vitro conditioning was examined using 2D DIGE and MS/MS analysis. The experiments involved four independent groups: conditioned and labeled 30 min or 3 hr post-conditioning, and the corresponding unpaired controls labeled 30 min or 3 hr post-treatment. The two time periods selected for study following one-trial in vitro conditioning were based upon the results of electrophysiological studies showing that conditioning-dependent short-term enhanced excitability observed in sensory neurons is detected 15–30 min post conditioning, while intermediate-term enhanced excitability reaches asymptote 3 hr post-conditioning (Crow and Xue-Bian, 2000; Crow and Siddiqi, 1997).

The small format 2D gels that were used in our analysis can resolve 1050–1250 protein spots with our experimental protocol. ImageMaster software and a computer template generated by manual selection from a master gel were used to screen the spots that could be reliably detected on each replicate gel from the experimental and control treatments. ImageMaster analysis of the gels detected more spots than the manual template, however not all spots detected from the ImageMaster analysis were found on all of the gels due to gel-to-gel variability. Therefore only protein spots detected on all of the replicate gels were selected for analysis. Verification of abundance changes between gels was provided by comparing the ImageMaster analysis of the same spots detected with a template generated by manual selection. Differential expression of individual protein spot abundance was assessed for the conditioned and corresponding unpaired control procedure for each time point from each analytical gel. Ratios of spot volumes from the conditioned samples relative to controls from each gel were computed followed by the application of a log transformation to help normalize the skewed distribution of ratios. The application of a standard score transformation of the log ratios provided for the detection of statistically significant changes in protein spot abundance from each gel. Fold abundance changes were calculated from the volume ratios and were used in computing descriptive statistics and inferential statistical comparisons between gels. A standard score of ±1.96 was used to determine statistically significant increases or decreases between groups in spot abundance (p<.05).

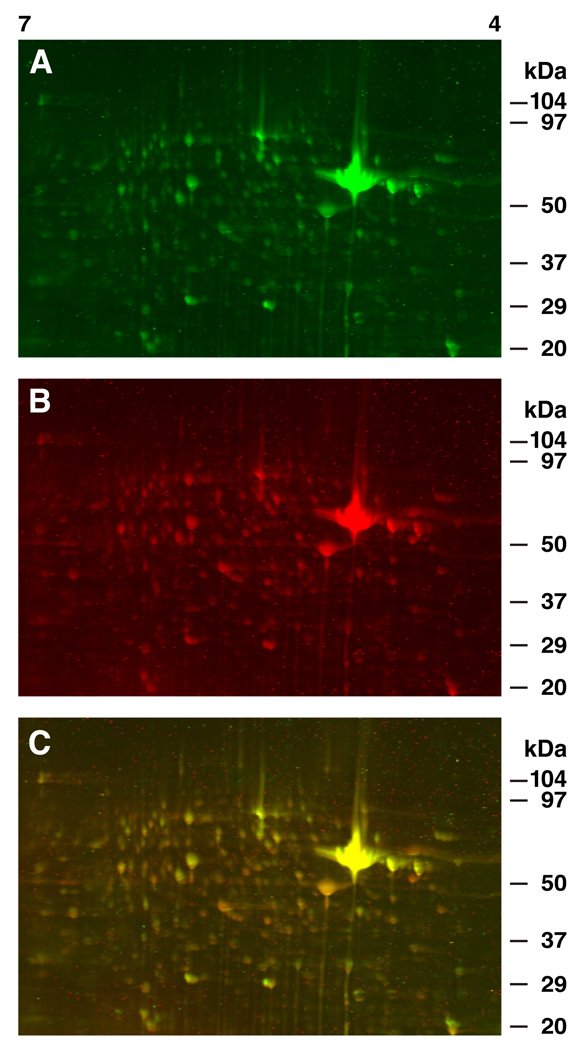

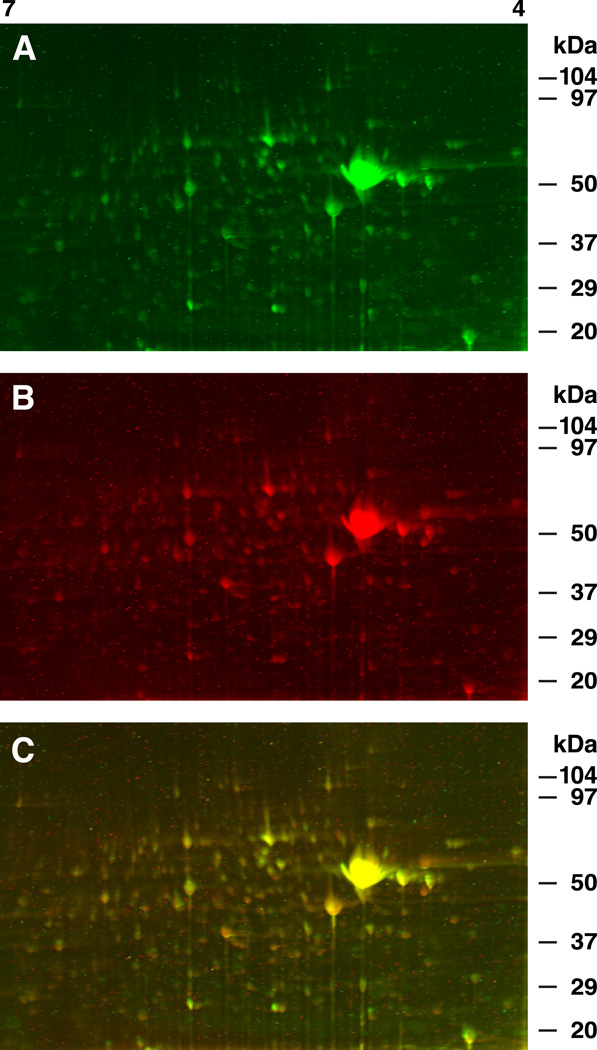

A representative example of 2D DIGE gels showing resolved protein spots from seven pooled circumesophageal nervous systems labeled 30 min post-conditioning is shown in Fig.1. The unpaired control sample is labeled with Cy3 (green), and the one-trial in vitro conditioned sample labeled with Cy5 (red). The color overlay of the Cy3 and Cy5 images shown in Fig.1 A–B is depicted in Fig 1C. Examples of 2D DIGE gels generated from conditioned and unpaired controls 3 hr post-conditioning are shown in Fig.2. The unpaired control sample is labeled with Cy3 (green) and the one-trial conditioned sample labeled with Cy5 (red). Regions of equal Cy3 and Cy5 signals in Figs.1 and 2 appear yellow. The statistical analysis of the analytical gels revealed that 25 protein spots expressed significant changes in abundance (p<.05) 30 min post-conditioning. The abundance changes exhibited a range from a 2.2-fold increase (spot #54) to a 1.54-fold decrease (spot #90).

Fig.1.

Representative example of 2D-DIGE gels showing resolved proteins from circumesophageal nervous systems labeled 30 min post-conditioning. (A) Unpaired control sample labeled with Cy3 (green). (B) one-trial in vitro conditioned sample labeled with Cy5 (red). (C) Color overlay of Cy3 and Cy5 images shown in A and B. Regions of equal Cy3 and Cy5 signals appear yellow. Internal control samples were labeled with Cy2 (blue, not shown) as described in the Methods.

Fig.2.

Representative example of 2D-DIGE gels showing resolved proteins from circumesophageal nervous systems labeled 3 hr post-conditioning. (A) Unpaired control sample labeled with Cy3 (green). (B) one-trial in vitro conditioned sample labeled with Cy5 (red). (C) Color overlay of Cy3 and Cy5 images shown in A and B. Regions of equal Cy3 and Cy5 signals appear yellow. Internal control samples were labeled with Cy2 (blue, not shown) as described in the Methods.

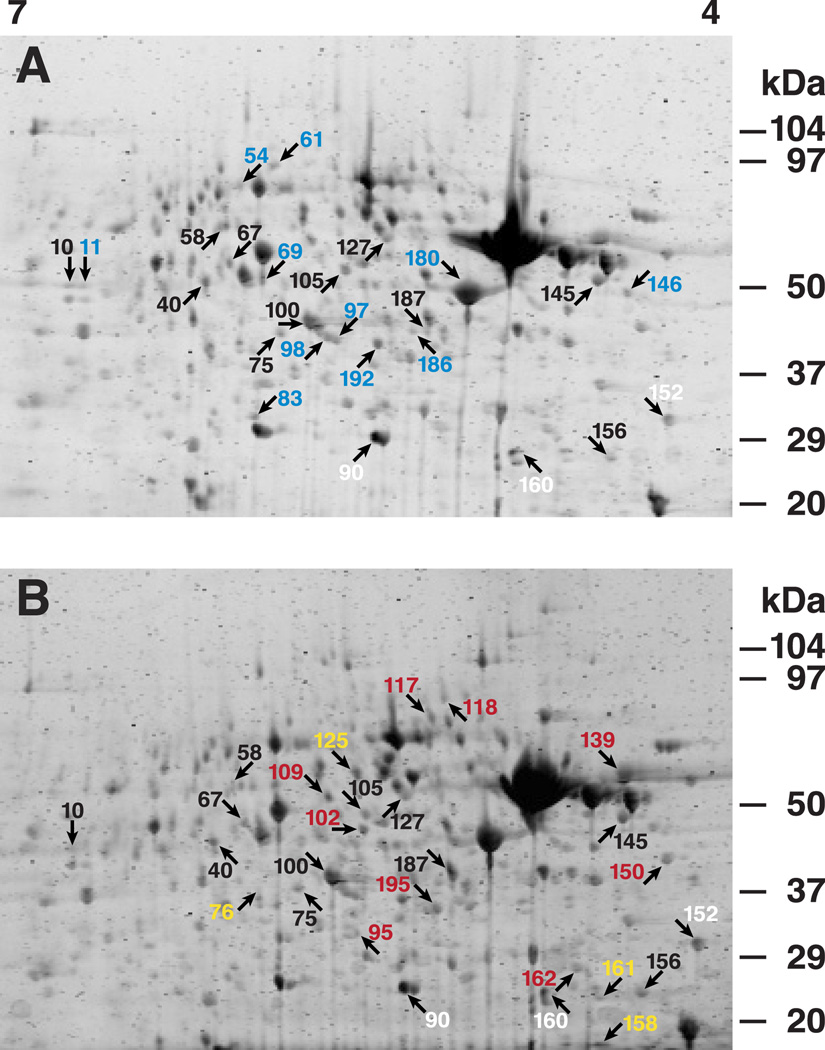

An examination of the longer post-conditioning time period revealed that 27 protein spots were significantly changed 3 hr post-conditioning. The changes ranged from a 1.88-fold increase (spot #145) to a 2.04-fold decrease (spot #90). The mean ratios for the statistically significant differentially regulated protein spots at the two time points post-conditioning are listed in Table 1. The spot numbers refer to the proteins designated by color coded numbers shown in Fig. 3A–B. Eleven protein spots that expressed increased abundance levels were common to both 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning. Eleven protein spots that expressed increased abundance levels only at 30 min post-conditioning were detected, and nine protein spots with increased abundance levels were detected only in the 3 hr group. Seven protein spots exhibited statistically significant decreased abundance levels relative to unpaired controls. Three of the protein spots that showed significant decreased abundance were common to both 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning, and four protein spots that showed a significant decrease in abundance were detected only in the 3 hr post-conditioning group.

Table 1.

Protein spots differentially regulated by one-trial in vitro conditioning

| Conditioned /unpaired 30 min | Conditioned /unpaired 3 hr | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spot Number | Mean ratio±SEM | Spot Number | Mean ratio±SEM |

| 10 | 1.28±.10 | 10 | 1.40±.13 |

| 11 | 1.27±.10 | 40 | 1.47±.18 |

| 40 | 1.63±.16 | 58 | 1.36±.08 |

| 54 | 2.20±.34 | 67 | 1.35±.15 |

| 58 | 1.55±.12 | 75 | 1.42±.18 |

| 61 | 1.49±.11 | 76 | −1.85±.13 |

| 67 | 1.45±.09 | 90 | −2.04±.09 |

| 69 | 1.51±.13 | 95 | 1.59±.13 |

| 75 | 1.68±.15 | 100 | 1.56±.12 |

| 83 | 1.32±.13 | 102 | 1.25±.14 |

| 90 | −1.54±.14 | 105 | 1.67±.20 |

| 97 | 1.78±.21 | 109 | 1.56±.11 |

| 98 | 1.72±.11 | 117 | 1.47±.12 |

| 100 | 1.78±.18 | 118 | 1.34±.09 |

| 105 | 1.66±.20 | 125 | −1.56±.10 |

| 127 | 1.72±.16 | 127 | 1.50±.13 |

| 145 | 1.95±.16 | 139 | 1.84±.25 |

| 146 | 1.37±.14 | 145 | 1.88±.21 |

| 152 | −1.35±.07 | 150 | 1.55±.08 |

| 156 | 1.52±.12 | 152 | −1.63±.10 |

| 160 | −1.47±.15 | 156 | 1.52±.14 |

| 180 | 1.80±.21 | 158 | −1.41±.12 |

| 186 | 1.28±.11 | 160 | −1.73±.14 |

| 187 | 1.55±.26 | 161 | −1.41±.10 |

| 192 | 1.70±.19 | 162 | 1.47±.11 |

| 187 | 1.51±.10 | ||

| 195 | 1.32±.08 | ||

Fig.3.

One-trial in vitro conditioning regulates protein abundance in circumesophageal nervous systems at different times post-conditioning. (A) 2D-DIGE image showing statistically significant differentially regulated protein spots (arrows) in the 30 min post-conditioning group. (B) 2D-DIGE image showing statistically significant differentially regulated spots (arrows) in the 3 hr post-conditioning group. Protein spots designated by black numbers showed significantly increased abundance at both 30 min and 3 hr, blue numbers significantly increased abundance only at 30 min, red numbers significantly increased abundance only at 3 hr. Protein spots designated by white numbers exhibited significantly decreased abundance at both 30 min and 3 hr, and spots designated by yellow numbers showed significantly decreased abundance only at 3 hr.

Protein spots whose abundance was statistically significant at the two times following one-trial conditioning relative to unpaired controls are indicated in the gels shown in Fig. 3. Protein spots common to both time points are indicated by the same color number (black), and protein spots unique to 30 min or 3 hr post-conditioning are designated by different color numbers in Fig. 3A–B, blue and red respectively. The statistical analysis (ANOVA) of the group data consisting of all replicates (n=6) revealed significant overall differences in protein spot abundance between conditioned and unpaired controls labeled 30 min post-conditioning (F(1,10)=6.4; p<.02) and labeled 3 hr post-conditioning (F(1,10)=5.7; p<.03). The interaction between groups and protein spots was also significant at 30 min (F(24,239)=8.1; p<.001) and 3 hr (F(26,260)=4.9; p<.001). The significant interaction reflects the observation that some protein spots expressed a decrease in abundance and other spots showed an increase in abundance at both 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning.

Protein identification and classification

Protein spots that expressed statistically significant changes in abundance from the 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning time points were selected for mass spectrometric analysis to determine protein identification. Following MS/MS analysis and the database search 34 proteins from the 30 min and 3 hr groups were identified. The identities of the protein spots from the two time points post-conditioning, the accession numbers in the NCBI database, degree of identity and sequence coverage are listed in Table 2. There were a few cases detected involving redundant proteins that most likely involved splice variants or post-translational modifications resulting in a shift in the isoelectric point of the protein. An example was isocitrate dehydrogenase that expressed a change in abundance at both 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning with a shift in pH detected at 30 min. In addition to the within-group redundancy, there were nine identified protein spots that showed changes in abundance that were common to both the 30 min and 3 hr time points (Table 2). Taking both within and between group redundancy into consideration, six identified protein spots were detected that were unique to the 30 min time point and nine identified protein spots were detected that were unique to the 3 hr post-conditioning time point. With respect to the 3 hr time point, five of the identified protein spots exhibited an increase in abundance and four a decrease in abundance (see Fig.3).

Table 2.

Differentially regulated proteins at 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning based upon MS/MS analysis

| Spot # | Protein | Accession ID | % ID | % Coverage |

Spot # | Protein | Accession ID | % ID | % Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 min | 3 hr | ||||||||

| 10 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | AAT44354 | 88 | 6 | 10 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | AAT44354 | 91 | 7 |

| 11 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | AAT44354 | 90 | 7 | 40 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | AAT44354 | 86 | 5 |

| 40 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | AAT44354 | 88 | 6 | 67 | Gelsolin | XP792912 | 89 | 7 |

| 61 | Ribosomal protein L4 | YP002910164 | 91 | 10 | 76 | Cytochrome P450 | YP001328927 | 95 | 10 |

| 67 | Gelsolin | XP792912 | 88 | 7 | 90 | Reductase-related protein | NP001191534 | 84 | 6 |

| 69 | Aminotransferase | ZP02152233 | 82 | 16 | 100 | GTP binding protein | Q08706 | 100 | 9 |

| 83 | Glutathione S-transferase | YP761780 | 77 | 6 | 117 | Intermediate filament protein A | CAA42839 | 87 | 6 |

| 90 | Reductase-related protein | NP001191534 | 80 | 5 | 118 | Heat shock protein | CAX65070 | 72 | 5 |

| 98 | Prohibitin-like isoform | XP002734318 | 82 | 16 | 125 | GMP synthase | ZP00996722 | 73 | 11 |

| 100 | GTP binding protein | Q08706 | 100 | 8 | 127 | Glucosamine-phosphate N-acetyltransferase | XP001515520 | 84 | 9 |

| 127 | Glucosamine-phosphate N-acetyltransferase | XP001515520 | 84 | 9 | 139 | Beta tubulin | AAP13560 | 100 | 33 |

| 146 | Glycosyltransferase | YP001377913 | 96 | 12 | 150 | Tropomyosin | BAB01765 | 78 | 15 |

| 152 | Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase | NP001191493 | 95 | 19 | 152 | Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase | NP001191493 | 94 | 16 |

| 156 | Calmodulin | EGI70237 | 88 | 12 | 156 | Calmodulin | EGI70237 | 90 | 13 |

| 180 | Actin | AA502073 | 100 | 8 | 158 | Allograft inflammatory factor | ABV01121 | 80 | 14 |

| 187 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase | XP002434451 | 68 | 8 | 161 | Ribosomal E-loop binding protein | ZP07018362 | 76 | 15 |

| 162 | Csp24 | AAN08024 | 100 | 23 | |||||

| 187 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase | XP002434451 | 84 | 11 | |||||

Spot # corresponds to those shown in Fig. 4.

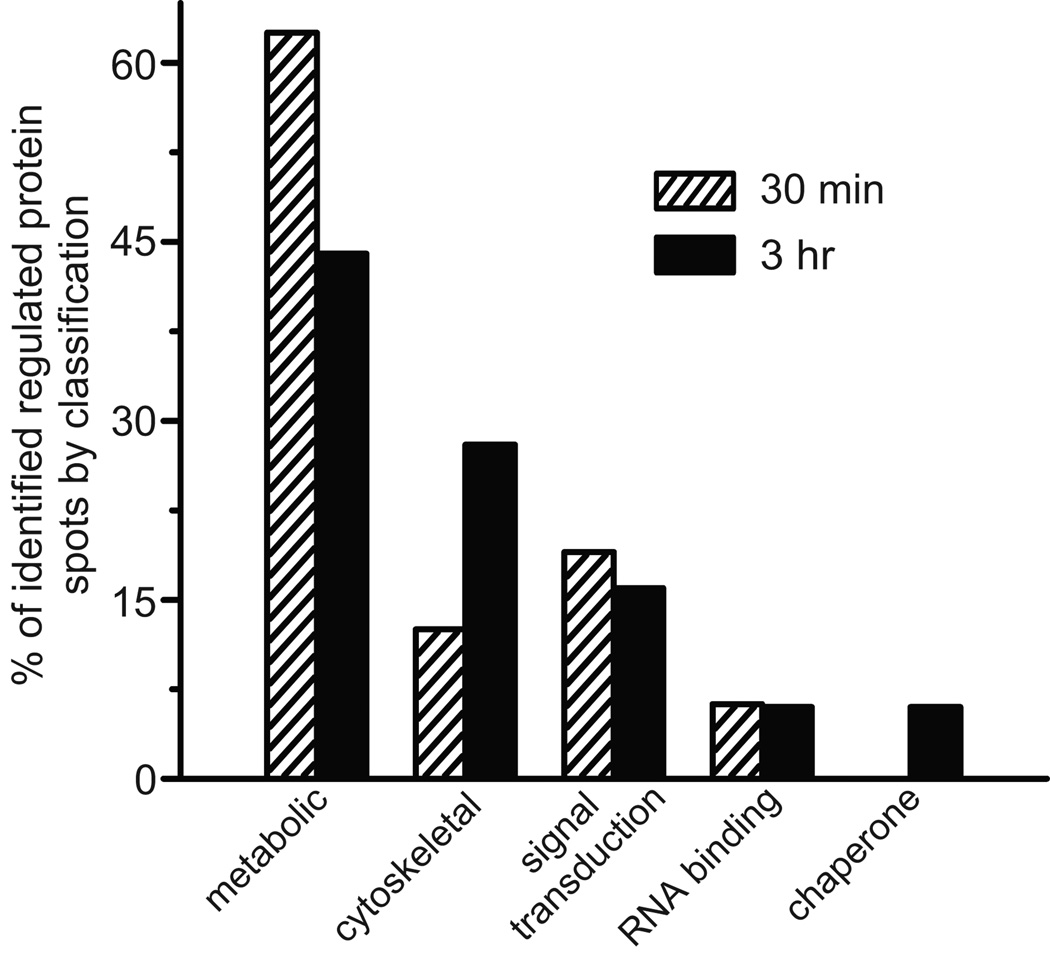

The protein spots that were sequenced by MS/MS were grouped into different functional classes based upon established information in the database and criteria reported in previous publications (see Gong et al. 2004; McNair et al. 2006, 2007; Piccoli et al. 2007; Henniger et al. 2007; Pinaud et al. 2008; Jüch et al. 2009). The proteins exhibited diverse functions such as cell signaling, cytoskeletal regulation, translational control, protein degradation, and metabolic activity (Fig. 4). The majority of the identified proteins that expressed differential abundance changes were metabolic enzymes. There was a general trend for a time-dependent decline in the number of identified metabolic enzymes exhibiting significant abundance changes. The percentage of significantly regulated metabolic enzymes was 62.5% at 30 min and 44% at 3 hr.

Fig.4.

Bar graphs summarizing the classification of identified differentially regulated protein spots 30 min post-conditioning and 3 hr post-conditioning. The data in the different bar graphs are expressed as the percentage of the total number of differentially expressed proteins identified by the MS/MS analysis for each time point post-conditioning.

There was an increase in the number of cytoskeletal related proteins in the samples exhibiting abundance changes at 3 hr post-conditioning (28%) as compared to 30 min post-conditioning (12.5%). Several actin-binding proteins expressed significant changes in abundance at both 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning. Tropomyosin expressed a significant increase in abundance at 3 hr post-conditioning, but not 30 min. The actin severing and caping protein gelsolin expressed an increase in abundance detected at both 30 min and 3 hr. The β-thymosin repeat actin binding protein Csp24 showed a significant increase in abundance at 3 hr. Actin exhibited an increased abundance only at 30 min post-conditioning and β-tubulin only at 3 hr post-conditioning. Intermediate filament protein A showed an increased abundance only in the 3 hr group.

Signal transduction proteins exhibited a similar increased abundance at both 30 min post-conditioning (19%) and 3 hr (17%). Guanine nucleotide-binding protein was increased in abundance at both 30 min and 3 hr, which is not surprising since 5-HT effects are mediated through a G-protein coupled receptor. The Ca2+ binding protein calmodulin was also increased at both 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning. A protein spot that expressed increased abundance at 30 min exhibited a sequence homology to a flotillin-like protein. The conserved band of flotillin-like proteins similar to prohibitin have been implicated in signal transduction, vesicle trafficking, cytoskeletal modifications, and protein-protein interactions.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have identified modifications of the proteome in Hermissenda associated with short-and intermediate-term memory formation produced by one-trial in vitro conditioning. Some of the proteins showed changes in abundance at both post-conditioning time periods, while other proteins expressed significant abundance changes only 30 min post-conditioning or 3 hr post-conditioning. A change in the abundance of the same 14 protein spots was detected for the groups labeled 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning. Eleven of the protein spots common to both time periods showed an increased abundance with conditioning and three expressed a decrease in abundance relative to unpaired controls. Eleven protein spots detected only at the 30 min time period expressed an increase in abundance relative to controls and nine protein spots detected 3 hr post-conditioning showed a significant increase in abundance. Four of the 13 protein spots that showed abundance changes unique to the 3 hr time expressed a decrease in abundance. The identity of 34 differentially regulated protein spots detected at 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning was determined by MS/MS analysis and database searches. The results of this study support the view that one-trial in vitro conditioning produces over-time a significant alteration in the abundance of a diverse range of proteins. The changes likely reflect a number of conditioning-dependent processes such as post-translational modifications of existing proteins, protein degradation and synthesis.

In a number of earlier studies of model systems the activation of second messengers, or the application of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators to the isolated nervous system or cultured neurons has been shown to increase the expression of several unidentified radiolabeled proteins (Barzilai et al. 1989; Eskin et al. 1989). More recently, studies employing 2DE or DIGE in conjunction with MS analysis have lead to the an investigation of activity-dependent dynamic changes in the proteome and the identification of proteins associated with synaptic activity and synaptic plasticity (McNair et al. 2006; Henniger et al. 2007; Piccoli et al. 2007; Pinaud et al. 2008; Jüch et al. 2009). These studies and the present findings have revealed a widespread alteration of the proteome associated with sensory activation, synaptic plasticity, and now, Pavlovian conditioning. Presenting a novel song for either 1 hr or 3 hr to songbirds resulted in a time-dependent differential regulation of 16 protein spots in the auditory forebrain; with three protein spots displaying altered abundance at both time periods (Pinaud et al. 2008). In the hippocampal slice, LTP resulted in 71 regulated proteins spots detected 10 min after induction and 51 regulated protein spots 4 hr post-induction (McNair et al. 2006). The analysis of the hippocampal proteome after 7 days of training on a spatial learning task in the Morris water maze identified changes in abundance of 76 different proteins, with over 60% showing a decrease in abundance (Henniger et al. 2007). In addition, modifying synaptic activity with bicuculin and TTX in cultured hippocampal neurons resulted in the identification of 57 proteins that showed altered expression (Piccoli et al. 2007), and a time-dependent change in protein abundance in olfactory bulbs was identified following learning in mice (Jüch et al. 2009).

Consistent with the time-dependent proteomic analysis of mammalian hippocampus and auditory stimulation of songbirds, our results show altered expression across a diverse range of protein classes. A majority of protein spots exhibiting altered abundance 30 min post-conditioning in Hermissenda, 10 min after LTP induction, and following 1 hr of auditory stimulation are associated with energy and metabolism (McNair et al. 2006; Pinaud et al. 2008). In agreement with the LTP results, we found that the percentage of protein spots related to metabolism, exhibiting altered abundance, decreased 3 hr post-conditioning, and cytoskeletal related proteins expressing altered abundance increased 3 hr post-conditioning as compared to 30 min post-conditioning. Early changes in protein abundance related to energy and metabolism is not suprising following procedures that increase neural and synaptic activity. The shift in the expression of cytoskeletal-related proteins at longer time periods produced by LTP and one-trial in vitro conditioning would be consistent with a role for proteins contributing to structural remodeling underlying the formation of persistent memory. There is an extensive literature on the potential role of the actin cytoskeleton contributing to examples of cellular/synaptic plasticity (e.g. Fifkova and Morales 1992; Kim and Lisman 1999). Morphological changes in spine shape and spine number have been proposed to contribute to synaptic plasticity (Calabrese et al. 2006). Dendritic spine shape and motility are determined by the cytoskeleton composed of F-actin filaments. Dynamic changes in the structure of dendritic spines may underlie the formation of long-term memory (for a recent review see Segal 2005). The significant increase in the abundance of tropomyosin shown here at 3 hr post-conditioning suggests a potential contribution to actin-based structural remodeling. Tropomyosin inhibits both the rate of polymerization and depolymerization of actin, regulates the actin-myosin interaction, and by the temporal and spatial regulation of its expression is involved with functional contributions to the actin cytoskeleton (Gunning et al. 2008). In addition, tropomyosin is a major regulator of F-actin functional specialization in migrating cells and is important for regionally defining the properties of the actin cytoskeleton in mediating changes in cell morphology (Gupton et al. 2005). Tropomyosin and troponin bind to actin and block myosin binding. Troponin binds to Ca2+, releasing tropomyosin from actin which allows the binding of myosin to actin. The phosphorylation of tropomyosin is involved in modulating the association of myosin with actin. DAP kinase has been shown to phosphorylate tropomyosin downstream of the ERK pathway to promote cytoskeletal remodeling (Houle et al. 2007). We have shown previously that two isoforms of tropomyosin exhibit significantly increased phosphorylation regulated by multi-trial Pavlovian conditioning (Crow and Xue-Bian 2010). In addition, recent research has shown that myosin II activity in the hippocampus contributes to an actin-dependent process supporting LTP-induced synaptic plasticity and memory formation (Rex et al. 2010). They proposed that LTP induction causes a myosin II-dependent polymerization of F-actin in dendritic spines that is required to stabilize early stage LTP.

The functional specificity of tropomyosin is related to collaborative interactions with different actin binding proteins. Therefore actin affinity may be modulated by other actin binding proteins such as cofilin, gelsolin, myosin and Arp2/3 (Gunning et al. 2008). Gelsolin is an actin severing and caping protein that modulates Ca2+ channel and NMDA receptor activities (Furukawa et al. 1997) and is a key regulator of actin filament assembly and disassembly. In this study our proteomic analysis revealed that the abundance of gelsolin was significantly increased at both 30 min and 3 hr post-conditioning. The actin binding protein Csp24, a member of the β-thymosin-like family of actin binding proteins that contain multiple actin binding domains, was also shown in the present study to exhibit an increase in abundance only at 3 hr post-conditioning. Down regulation of thymosin β4 has been reported to increase AMPA receptor expression (Mollinari et al. 2009). The present results compliment our previous study showing that enhanced excitability detected after one-trial in vitro conditioning is blocked by antisense oligonucleotide-mediated downregulation of Csp24 (Crow et al. 2003). Previous work has shown that Csp24 is phosphorylated by one-trial in vitro conditioning and multi-trial Pavlovian conditioning (Crow et al. 1999, 2003; Crow and Xue-Bian 2000, 2003, 2007, 2010; Redell et al. 2007). The depolarized shift in the activation curve of IA proposed to contribute to one-trial conditioning-dependent enhanced excitability is blocked by preincubation of sensory neurons with Csp antisense oligonucleotide (Yamoah et al. 2005).

In addition to providing the opportunity to detect abundance changes in large assemblies of proteins at the same time following one-trial in vitro conditioning, a primary reason for using a proteomics approach to study memory consolidation is to identify proteins not previously associated with this complex process. Two proteins of interest not previously identified in proteomic studies of learning were detected in the present report. AIF-1 is a cytokine-inducible, Ca2+-binding, actin-polymerizing and Rac1-activating protein associated with vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation (Autieri et al. 2003). In addition, a conserved domain was identified from a flotillin-like protein similar to prohibitin that has been implicated in signal transduction, vesicle trafficking, cytoskeletal modifications, and regulation of cell proliferation (Mishra et al. 2006).

Two proteins that have been previously shown to be regulated by conditioning and plasticity in Hermissenda were not identified by our proteomic analysis. Calexitin (CE) is a GTP- and Ca2+ binding protein that is phosphorylated by PKC and is proposed to contribute to conditioning-dependent enhanced excitability by K+- inactivation (Neary et al. 1981; Nelson et al. 1986; Ascoli et al. 1997). Immunostaining of CE is significantly increased in identified type B photoreceptors following a conditioning protocol that produced long-term memory (Kuzirian et al. 2001). Since CE is primarily in the eyes and a restricted number of cells in regions of the nervous system that have been proposed to be unaffected by conditioning, the proteomic analysis conducted on whole nervous systems in the present study may not have been sensitive enough to detect this low abundant protein. Alternatively, CE may have been one of a number of differentially regulated protein spots that could not be reliably differentiated from adjacent proteins located for extraction from the 2D gels for MS analysis. In addition, the adapter protein 14-3-3 was not identified in our proteomic analysis. We previously showed using 1D gel analysis that 14-3-3 is found in the Hermissenda circumesophageal nervous system, MS analysis revealed peptide sequences that are homologous to 14-3-3 proteins and post-translational modification of Csp24 regulates its interaction with 14-3-3 (Crow et al. 2007). Again, our analysis of whole nervous system lysates may have masked less abundant proteins or we may not have been able to reliably identify these protein spots for picking and subsequent MS identification.

Many contemporary reviews of the extensive literature on cellular and synaptic plasticity that may underlie long-term memory have argued that there are three distinct mechanistic components associated with the induction and maintenance of memory. An initial phase depending upon post-translational modification of existing proteins, an intermediate phase dependent upon the synthesis of new protein via translation but not dependent upon transcription, and a persistent phase that depends upon both the synthesis of new protein and gene transcription and the synthesis of new mRNA. The time windows for the three stages may vary according to different learning paradigms, species, and level of initial training. Further, it has been proposed that these multiple mechanistically distinct stages may be a general feature of cellular and synaptic plasticity underlying memory formation since they have been detected across multiple species and different models of cellular plasticity (Cobb and Pitt 2008). A comprehensive analysis of mechanistically distinct stages of memory formation will require an investigation of the dynamic changes in the proteome over-time produced by learning.

In conclusion, the application of a proteomics approach using 2D-DIGE and MS/MS has lead to the identification of proteins expressing altered abundance levels associated with short-term and intermediate-term memory formation. The proteomic analysis revealed that identified proteins are involved in diverse cellular functions such as translational regulation, cell signaling, cytoskeletal regulation, metabolic activity, and protein degradation. The general trend of an increase in the number of cytoskeletal related proteins with increased abundance and a decrease in the abundance of metabolic enzymes over-time, suggests that some of the identified proteins may contribute to structural remodeling associated with memory formation. Tropomyosin, gelsolin and the β-thymosin repeat actin binding protein Csp24 are proteins that are regulated by one-trial in vitro conditioning over-time that could contribute to structural changes supporting memory formation. Although the precise role of the actin cytoskeleton in memory is poorly understood, it is well documented that actin can be dynamically regulated by a number of cellular signals. In neurons, actin binding proteins may regulate the distribution of ion channels and alter receptor trafficking. The interaction between Csp24 and cytoskeletal proteins identified in our proteomic analysis may be important in regulating ion channel localization supporting enhanced intrinsic excitability produced by Pavlovian conditioning in Hermissenda.

Highlights.

-

>

A quantitative proteomic analysis of Hermissenda nervous system lysates was used to identify proteins associated with memory formation.

-

>

Changes in protein abundance were examined with difference gel electrophoresis, quantification of experimental and control abundance ratios and mass spectrometry.

-

>

Different proteins regulated by one-trial conditioning are associated with short-term (30 min) and intermediate-term (3 hr) memory.

-

>

The increased abundance of cytoskeletal-related proteins such as Csp24 and tropomyosin may contribute to structural remodeling underlying memory formation.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. O’Brien for the use of the Typhoon scanner. This research was supported by NIMH grant MH40860 to T.C.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ASW

artificial seawater

- CE

calexcitin

- CS

conditioned stimulus

- Csp24

24 kDa phosphoprotein (accession number AAN08024)

- IA

A-type transient K+ current

- IEF

isoelectric focusing

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MALDI-TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight

- MS

mass spectrometry

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- 2D-DIGE

two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis

- US

unconditioned stimulus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Alban A, David S, Bjorkesten L, Andersson C, Sloge E, Lewis S, Currie I. A novel experimental design for comparative two-dimensional gel analysis: Two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis incorporating a pooled internal standard. Proteomics. 2003;3:36–44. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200390006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberini CM. The role of protein synthesis during the labile phases of memory: Revisiting the skepticism. Neurobio Learn Mem. 2008;89:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli G, Liu KX, Olds JL, Nelson TJ, Gusov PA, Bertucci C, Bramanti E, Raffaelli A, Salvador P, Alkon DL. Secondary structure of Ca2+-induced conformational change of calexcitin, a learning associated protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29771–29779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autieri MV, Kelemen SE, Wendt KW. AIF-1 is an actin-polymerizing and rac1-activating protein that promotes vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Cir Res. 2003;92:1107–1114. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000074000.03562.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DJ, Kim JJ, Sun W, Thompson RF, Helmstetter FJ. Acquisition of fear conditioning in rats requires the synthesis of mRNA in the amygdala. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113:276–282. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai A, Kennedy TE, Sweat JD, Kandel ER. 5-HT modulates protein synthesis and the expression of specific proteins during long-term facilitation in Aplysia sensory neurons. Neuron. 1989;2:1577–1586. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Ann of Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw KD, Emptage NJ, Bliss TV. A role for dendritic protein synthesis in hippocampal late LTP. J Neurosci. 2003;18:3150–3152. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese B, Wilson MS, Halpain S. Development and regulation of dendritic spine synapses. Physiology. 2005;21:38–47. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00042.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb SR, Pitt A. Proteomics in the study of hippocampal plasticity. Ex Rev Proteom. 2008;5:393–404. doi: 10.1586/14789450.5.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Forrester J. Light paired with serotonin mimics the effects of conditioning on phototactic behavior in Hermissenda. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7975–7978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Forrester J. Light paired with serotonin in vivo produces both short and long-term enhancement of generator potentials of identified B-photoreceptors in Hermissenda. J Neurosci. 1991;11:608–617. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00608.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Forrester J. Protein kinase inhibitors do not block the expression of established enhancement in identified Hermissenda B-photoreceptors. Brain Res. 1993;613:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90454-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Siddiqi V, Zhou Q, Neary JT. Time-dependent increase in protein phosphorylation following one-trial enhancement in Hermissenda. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1736–1741. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66041736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Siddiqi V, Dash P. Long-term enhancement but not short-term in Hermissenda is dependent upon mRNA synthesis. Neurobio Learn Mem. 1997;68:343–350. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1997.3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Siddiqi V. Time-dependent changes in excitability following one-trial conditioning of Hermissenda. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:3460–3464. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Xue-Bian JJ, Siddiqi V, Kang Y, Neary JT. Phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by one-trial and multi-trial classical conditioning. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3480–3487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03480.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Xue-Bian JJ, Siddiqi V. A protein synthesis-dependent and mRNA synthesis-independent intermediate phase of memory in Hermissenda. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:495–500. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Xue-Bian JJ. Identification of a 24 kDa phosphoprotein associated with an intermediate stage of memory in Hermissenda. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-j0002.2000. RC74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Xue-Bian JJ. One-trial conditioning regulates a cytoskeletal-related protein (CSP24) in the CS pathway of Hermissenda. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10514–10518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10514.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Redell J, Xue-Bian JJ, Tian LM, Dash P. Inhibition of conditioned stimulus pathway phosphoprotein 24 expression blocks the development of intermediate-term memory in Hermissenda. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3415–3422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03415.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Xue-Bian JJ. One-trial in vitro conditioning of Hermissenda regulates phosphorylation of Ser-122 of Csp24. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1112:189–200. doi: 10.1196/annals.1415.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Xue-Bian JJ, Neary JT. 14-3-3 proteins interact with the β-thymosin repeat protein Csp24. Neurosci Lett. 2007;424:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow T, Xue-Bian JJ. Proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications in conditioned Hermissenda. Neurosci. 2010;165:1182–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeZazzo J, Tully T. Dissection of memory formation from behavioral pharmacology to molecular genetics. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:212–218. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93905-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudai Y. Molecular basis of long-term memories: A question of persistence. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:211–216. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00305-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskin A, Garcia KS, Byrne JH. Information storage in the nervous system of Aplysia:specific proteins affected by serotonin and cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86:2458–2462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli MS, Corbet J, Dunn MJ, Dolphin AC, Bliss TV. Changes in protein synthesis accompanying long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus in vivo. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1346–1353. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01346.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fifkova E, Morales M. Actin matrix of dendritic spines, synaptic plasticity, and long-term potentiation. Int Rev Cytol. 1992;139:267–307. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61414-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flensburg J, Liminga M. Sequencing of tryptic peptides using chemically assisted fragmentation and maldi-psd. In: Walker JM, editor. The proteomics protocols handbook. New Jersey: Humana Press; 2005. pp. 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman FM, Rose SPR, Scholey A. Two time windows of anisomycin-induced amnesia for passive avoidance training in the day-old chick. Neurobio Learn Mem. 1995;63:291–295. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freider B, Allweis C. Transient hypoxic-amnesia: evidence for a triphasic memory-consolidating mechanism with parallel-processing. Behav Biol. 1978;22:178–189. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(78)92200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Frey S, Schollmeier F, Krug M. Influence of actinomycin D, a RNA synthesis inhibitor, on long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal neurons in vivo and in vitro. J Physiol. 1996;490:703–711. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Fu W, Li Y, Witke W, Kwiatkowski DJ, Mattson MP. The actin-severing protein gelsolin modulates calcium channel and NMDA receptor activities and vulnerability to excitotaxicity in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8178–8186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardi M, Montarolo PG, Kandel ER. A novel intermediate stage in the transition between short-and long-term facilitation in the sensory to motor neuron synapse of Aplysia. Neuron. 1995;14:413–420. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold PE. Protein synthesis and memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:199–200. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong L, Puri M, Ünlü M, Young M, Robertson K, Viswanathan S, Krishnaswamy A, Dowd SR, Minden JS. Drosophila ventral furrow morphogenesis:a poteomic analysis. Development. 2004;131:643–656. doi: 10.1242/dev.00955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning P, O’Neill G, Hardeman E. Tropomyosin-based regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in time and space. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1–35. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupton SL, Anderson KL, Kole TP, Fischer RS, Ponti A, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE, Danuser G, Fouler VN, Wirtz D, Hanein D, Waterman-Storer CM. Cell migration without a lamellipodium:translation of actin dynamics into cell movements mediated by tropomyosin. J Cell Biol. 2005;158:619–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins RD, Kandel ER, Bailey CH. Molecular Mechanisms of Memory Storage in Aplysia. Biol Bull. 2006;210:174–191. doi: 10.2307/4134556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henninger N, Feldmann RE, Jr, Futterer CD, Schrempp C, Maurer MH, Waschke KF, Kuschinsky W, Schwab S. Spatial learning induces predominant downregulation of cytosolic proteins in the rat hippocampus. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:128–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez PJ, Abel T. The role of protein synthesis in memory consolidation: Progress amid decades of debate. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:293–311. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle F, Poirier A, Dumaresq J, Huot J. DAP kinase mediates the phosphorylation of tropomyosin-1 downstream of the ERK pathway, which regulates the formation of stress fibers in response to oxidative stress. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3666–3677. doi: 10.1242/jcs.003251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Li XC, Kandel ER. cAMP contributes to mossy fiber LTP by initiating both a covalently mediated early phase and macromolecular synthesis-dependent late phase. Cell. 1994;79:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jüch M, Smalla KH, Kahne T, Lubec G, Tischmeyer W, Gundelfinger ED, Engelmann M. Congenital lack of nNOS impairs long-term social recognition memory and alters the olfactory bulb proteome. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92:469–484. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory storage: A dialog between genes and synapses. Science. 2001;294:1030–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1067020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Schuman EM. A requirement for local protein synthesis in neurotrophin-induced hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 1996;273:1402–1406. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C-H, Lisman J. A role of actin filament in synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4314–4324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04314.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klann E, Sweatt JD. Altered protein synthesis is a trigger for long-term memory formation. Neurobiol Learng Mem. 2008;89:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzirian AM, Epstein HT, Buck D, Child FM, Nelson T, Alkon DL. Pavlovian conditioning-specific increases od the Ca2+-and GTP-binding protein, calexcitin in identified Hermissenda visual cells. J Neurocytol. 2001;12:993–1008. doi: 10.1023/a:1021836723609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PR, Cohen JE, Becker KG, Fields RD. Gene expression in the conversion of early-phase to late phase long term potentiation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1048:259–271. doi: 10.1196/annals.1342.023. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. Memory-a century of consolidation. Science. 2000;287:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5451.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair K, Davies CH, Cobb SR. Plasticity-related regulation of the hippocampal proteome. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:575–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair K, Broad J, Riedel G, Davies CH, Cobb SR. Global changes in the hippocampal proteome following exposure to an enriched environment. Neurosci. 2007;145:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Murphy LC, Murphy LJ. The prohibitins: emerging roles in diverse functions. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:353–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollinari C, Ricci-Vitiani L, Pieri M, Lucantoni C, Rinaldi AM, Racaniello M, De Maria R, Zona C, Pallini R, Merlo D, Garaci E. Downregulation of thymosin β4 in neural progenitor grafts promotes spinal cord regeneration. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:4195–4207. doi: 10.1242/jcs.056895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary JT, Crow T, Alkon DL. Change in a specific phosphoprotein band following associative learning in Hermissenda. Nature. 1981;293:658–660. doi: 10.1038/293658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TJ, Cavallaro S, Yi CL, McPhie D, Schreurs BG, Gusev PA, Favit A, Zohar O, Jim J, Beushaisen S. Calexitin:a signalaling protein that binds calcium and GTP, inhibits potassium channels, and enhances membrane excitability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13808–13813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng K, Gibbs ME. Phases in memory formation: a review. In: Andrew RJ, editor. Neural and behavioral plasticity: the use of the domestic chick as a model. Oxford, UK: 1991. pp. 351–369. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PV, Kandel ER. Brief Ø-burst stimulation induces a transcription-dependent late phase of LTP requiring CAMP in area CA1 of the mouse hippocampus. Learn Mem. 1997;4:230–243. doi: 10.1101/lm.4.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani S, Marshall CJ, Tate WP, Goddard GV, Abraham WC. Maintenance of long-term potentiation in rat dentate gyrus requires protein synthesis but not messenger RNA synthesis immediately post-tetanization. Neurosci. 1989;28:519–526. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker D, Grillner S. Long-lasting substance-P-mediated modulation of NMDA –induced rhythmic activity in the lamprey locomotor network involves separate RNA- and protein-synthesis-dependent stages. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1515–1522. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccoli G, Verpelli C, Tonna N, Romorini S, Alessio M, Nairn AC, Bachi A, Sala C. Proteomic analysis of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3203–3215. doi: 10.1021/pr0701308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinaud R, Osorio C, Alzate O, Jarvis E. Profiling of experience-regulated proteins in the songbird auditory forebrain using quantitative proteomics. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:1409–1422. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redell JB, Xue-Bian JJ, Bubb MR, Crow T. One-trial in vitro conditioning regulates an association between the β-thymosin repeat protein Csp24 and actin. Neurosci. 2007;148:413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex CS, Gavin CF, Rubio MD, Kramar EA, Chen LY, Jia Y, Huganir RL, Muzyczka N, Gall CM, Miller CA, Lynch G. Myosin IIb regulates actin dynamics during synaptic plasticity and memory formation. Neuron. 2010;67:603–617. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LA, Large CH, Higgins MJ, Stone TW, O’Shaughnessy CT, Morris BJ. Increased expression of dendritic mRNA following the induction of long-term potentiation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;56:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig MR, Bennett EL, Colombo PJ, Lee PW, Serrano PA. Short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term memories. Behav Brain Res. 1993;57:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90135-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routtenberg A. The substrate for long-lasting memory: If not protein synthesis, then what? Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy JW. Is there a baby in the bathwater? Maybe: Some methodological issues for the de novo protein synthesis hypothesis. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilhab TS, Christoffersen GR. Role of protein synthesis in the transition from synaptic short-term to long-term depression in neurons of Helix pomatia. Neurosci. 1996;73:999–1007. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal M. Dendritic spines and long-term plasticity. Nat Rev. 2005;6:277–284. doi: 10.1038/nrn1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Knowlton B, Musen G. The structure and organization of memory. Ann Rev Psychol. 1993;44:453–495. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Bagnall MW, Sharma SK, Shobe J, Carew TJ. Intermediate-term memory for site-specific sensitization in Aplysia is maintained by persistent activation of protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3600–3609. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1134-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ünlü M, Morgan M, Minden J. Difference gel electrophoresis: A single gel method for detecting changes in protein extracts. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2071–2077. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan S, Ünlü M, Minden J. Two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis. Nat Protocols. 2006;Vol. 1(No. 3):1351–1358. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder DG, Mansuy IM, Osman M, Moallem TM, Kandel ER. Genetic and pharmacological evidence for a novel, intermediate phase of long-term potentiation suppressed by calcineurin. Cell. 1998;92:25–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia SZ, Feng CH, Guo AK. Multiple-phase model of memory consolidation confirmed by behavioral and pharmacological analyses of operant conditioning in Drosophia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:809–816. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamoah EN, Levic S, Redell J, Crow T. Inhibition of conditioned stimulus pathway phosphoprotein 24 expression blocks the reduction in A-type transient K+ current produced by one-trial in vitro conditioning of Hermissenda. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4793–4800. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5256-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin JCP, Wallach JS, Del Vecchio M, Wilder EL, Zhou H, Quinn WG, Tully T. Induction of a dominant negative CREB transgene specifically blocks long-term memory in Drosophila. Cell. 1994;79:49–58. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]