In 2010, more than 85% of the corn acreage and more than 90% of the soybean acreage in the USA was planted with genetically modified (GM) crops (USDA, 2010). Most of those crops contained transgenes from other species, such as bacteria, that confer resistance to herbicides or tolerance to insect pests, and that were introduced into plant cells using Agrobacterium or other delivery methods. The resulting ‘transformed’ cells were regenerated into GM plants that were tested for the appropriate expression of the transgenes, as well as for whether the crop posed an unacceptable environmental or health risk, before being approved for commercial use. The scientific advances that enabled the generation of these GM plants took place in the early 1980s and have changed agriculture irrevocably, as evidenced by the widespread adoption of GM technology. They have also triggered intense debates about the potential risks of GM crops for human health and the environment and new forms of regulation that are needed to mitigate this. There is also continued public resistance to GM crops, particularly in Europe.

Plant genetic engineering is at a technological inflection point

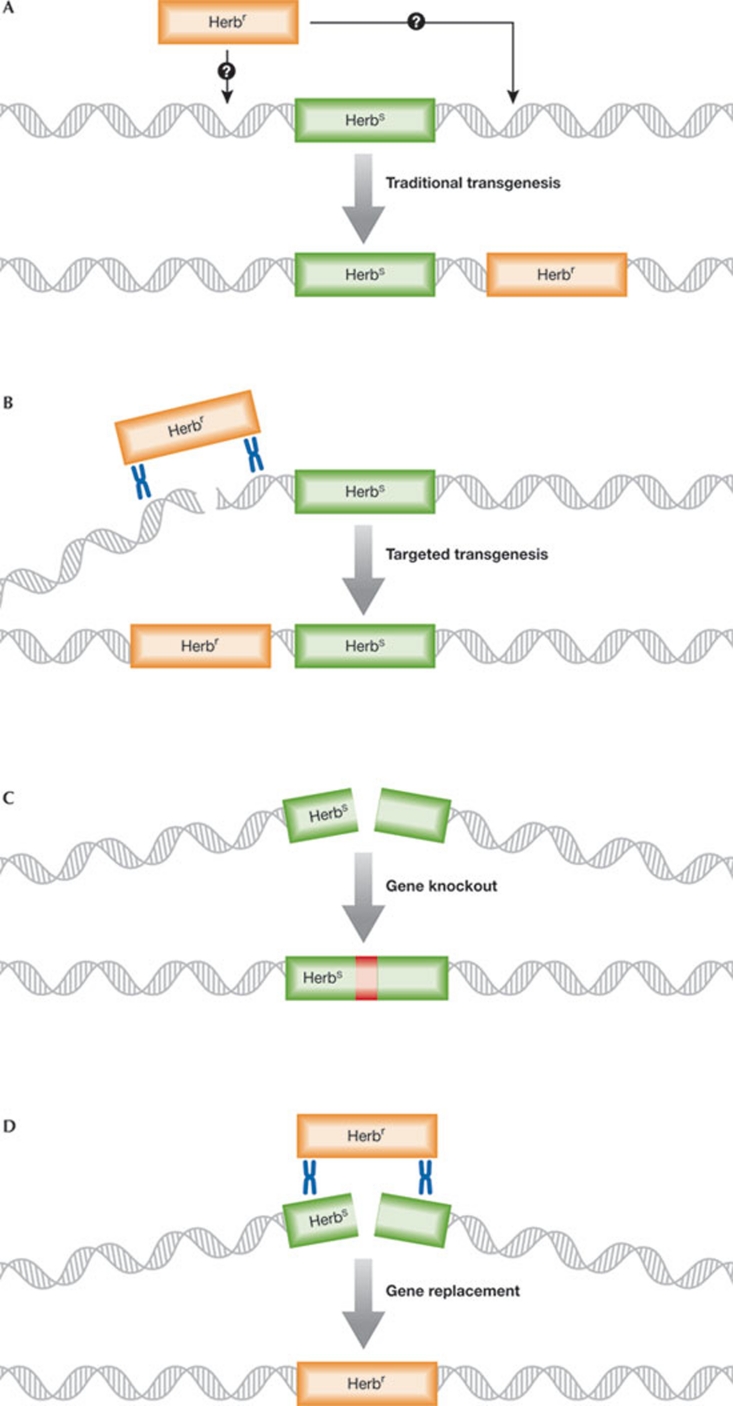

Plant genetic engineering is at a technological inflection point. New technologies enable more precise and subtler modification of plant genomes (Weinthal et al, 2010) than the comparably crude methods that were used to create the current stock of GM crops (Fig 1A). These methods allow scientists to insert foreign DNA into the plant genome at precise locations, remove unwanted DNA sequences or introduce subtle modifications, such as single-base substitutions that alter the activity of individual genes. They also raise serious questions about the regulation of GM crops: how do these methods differ from existing techniques and how will the resulting products be regulated? Owing to the specificity of these methods, will resulting products fall outside existing definitions of GM crops and, as a result, be regulated similarly to conventional crops? How will the definition and regulation of GM crops be renegotiated and delineated in light of these new methods?

Figure 1.

Comparing traditional transgenesis, targeted transgenesis, targeted mutagenesis and gene replacement. (A) In traditional transgenesis, genes introduced into plant cells integrate at random chromosomal positions. This is illustrated here for a bacterial gene that confers herbicide resistance (Herbr). The plant encodes a gene for the same enzyme, however due to DNA-sequence differences between the bacterial and plant forms of the gene, the plant gene does not confer herbicide resistance (Herbs). (B) The bacterial herbicide-resistance gene can be targeted to a specific chromosomal location through the use of engineered nucleases. The nucleases recognize a specific DNA sequence and create a chromosome break. The bacterial gene is flanked by sequences homologous to the target site and recombines with the plant chromosome at the break site, resulting in a targeted insertion. (C) Engineered nucleases can be used to create targeted gene knockouts. In this illustration, a second nuclease recognizes the coding sequence of the Herbs gene. Cleavage and repair in the absence of a homologous template creates a mutation (orange). (D) A homologous DNA donor can be used to repair targeted breaks in the Herbs gene. This allows sequence changes to be introduced into the native plant gene that confer herbicide resistance. Only a single base change is needed in some instances.

Of the new wave of targeted genetic modification (TagMo) techniques, one of the most thoroughly developed is TagMo, which uses engineered zinc-finger nucleases or meganucleases to create DNA double-stranded breaks at specific genomic locations (Townsend et al, 2009; Shukla et al, 2009; Gao et al, 2010). This activates DNA repair mechanisms, which genetic engineers can use to alter the target gene. If, for instance, a DNA fragment is provided that has sequence similarity with the site at which the chromosome is broken, the repair mechanism will use this fragment as a template for repair through homologous recombination (Fig 1B). In this way, any DNA sequence, for instance a bacterial gene that confers herbicide resistance, can be inserted at the site of the chromosome break. TagMos can also be used without a repair template to make single-nucleotide changes. In this case, the broken chromosomes are rejoined imprecisely, creating small insertions or deletions at the break site (Fig 1C) that can alter or knock out gene function.

TagMo technology would, therefore, challenge regulatory policies both in the USA and, even more so, in the [EU]…

The greatest potential of TagMo technology is in its ability to modify native plant genes in directed and targeted ways. For example, the most widely used herbicide-resistance gene in GM crops comes from bacteria. Plants encode the same enzyme, but it does not confer herbicide resistance because the DNA sequence is different. Yet, resistant forms of the plant gene have been identified that differ from native genes by only a few nucleotides. TagMo could therefore be used to transfer these genes from a related species into a crop to replace the existing genes (Fig 1D) or to exchange specific nucleotides until the desired effect is achieved. In either case, the genetic modification would not necessarily involve transfer of DNA from another species. TagMo technology would, therefore, challenge regulatory policies both in the USA and, even more so, in the European Union (EU). TagMo enables more sophisticated modifications of plant genomes that, in some cases, could be achieved by classical breeding or mutagenesis, which are not formally regulated. On the other hand, TagMo might also be used to introduce foreign genes without using traditional recombinant DNA techniques. As a result, TagMo might fall outside of existing US and EU regulatory definitions and scrutiny.

In the USA, federal policies to regulate GM crops could provide a framework in which to consider the way TagMo-derived crops might be regulated (Fig 2; Kuzma & Meghani, 2009; Kuzma et al, 2009; Thompson, 2007; McHughen & Smyth, 2008). In 1986, the Office of Science and Technology Policy established the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology (CFRB) to oversee the environmental release of GM crops and their products (Office of Science and Technology Policy, 1986). The CFRB involves many federal agencies and is still in operation today (Kuzma et al, 2009). It was predicated on the views that regulation should be based on science and that the risks posed by GM crops were the “same in kind” as those of non-GM products; therefore no new laws were deemed to be required (National Research Council, 2000).

Figure 2.

Brief history of the regulation of genetic engineering (Kuzma et al, 2009). EPA, Environmental Protection Agency; FIFRA, Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FPPA, Farmland Protection Policy Act; GMO, genetically modified organism; TOSCA, Toxic Substances Control Act; USDA, United States Department of Agriculture.

Various old and existing statutes were interpreted somewhat loosely in order to oversee the regulation of GM plants. Depending on the nature of the product, one or several federal agencies might be responsible. GM plants can be regulated by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) under the Federal Plant Pest Act as ‘plant pests’ if there is a perceived threat of them becoming ‘pests’ (similarly to weeds). Alternatively, if they are pest-resistant, they can be interpreted as ‘plant pesticides’ by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act. Each statute requires some kind of pre-market or pre-release biosafety review—evaluation of potential impacts on other organisms in the environment, gene flow between the GM plant and wild relatives, and potential adverse effects on ecosystems. By contrast, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) treats GM food crops as equivalent to conventional food products; as such, no special regulations were promulgated under the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act for GM foods. The agency established a pre-market consultation process for GM and other novel foods that is entirely voluntary.

…TagMo-derived crops come in several categories relevant to regulation…

Finally, and important for our discussion, the US oversight system was built mostly around the idea that GM plants should be regulated on the basis of characteristics of the end-product and not on the process that is used to create them. In reality, however, the process used to create crops is significant, which is highlighted by the fact that the USDA uses a process-based regulatory trigger (McHughen & Smyth, 2008). Instead of being inconsequential, it is important for oversight whether a plant is considered to be a result of GM.

How will crops created by TagMo fit into this regulatory framework? If only subtle changes were made to individual genes, the argument could be made that the products are analogous to mutated conventional crops, which are neither regulated nor subject to pre-market or pre-release biosafety assessments (Breyer et al, 2009). However, single mutations are not without risks; for example, they can lead to an increase in expressed plant toxins (National Research Council, 1989, 2000, 2002, 2004; Magana-Gomez & de la Barca 2009). Conversely, if new or foreign genes are introduced through TagMo methods, the resulting plants might not differ substantially from existing GM crops. Thus, TagMo-derived crops come in several categories relevant to regulation: TagMo-derived crops with inserted foreign DNA from sexually compatible or incompatible species; TagMo-derived crops with no DNA inserted, for instance those in which parts of the chromosome have been deleted or genes inactivated; and TagMo-derived crops that either replace a gene with a modified version or change its nucleotide sequence (Fig 1).

TagMo-derived crops with foreign genetic material inserted are most similar to traditional GM crops, according to the USDA rule on “Importation, Interstate Movement, and Release Into the Environment of Certain Genetically Engineered Organisms”, which defines genetic engineering as “the genetic modification of organisms by recombinant DNA (rDNA) techniques” (USDA, 1997). In contrast to conventional transgenesis, TagMo enables scientists to predefine the sites into which foreign genes are inserted. If the site of foreign DNA insertion has been previously characterized and shown to have no negative consequences for the plant or its products, then perhaps regulatory requirements to characterize the insertion site and its effects on the plant could be streamlined.

TagMo might be used to introduce foreign DNA from sexually compatible or incompatible species into a host organism, either by insertion or replacement. For example, foreign DNA from one species of Brassica—mustard family—can be introduced into another species of Brassica. Alternatively, TagMo might be used to introduce foreign DNA from any organism into the host, such as from bacteria or animals into plants. Arguments have been put forth advocating less stringent regulation of GM crops with cisgenic DNA sequences that come from sexually compatible species (Schouten et al, 2006). Russell and Sparrow (2008) critically evaluate these arguments and conclude that cisgenic GM crops may still have novel traits in novel settings and thus give rise to novel hazards. Furthermore, if cisgenics are not regulated, it might trigger a public backlash, which could be more costly in the long run (Russell & Sparrow, 2008). TagMo-derived crops with genetic sequences from sexually compatible species should therefore still be considered for regulation. Additional clarity and consistency is needed with respect to how cisgenics are defined in US regulatory policy, regardless of whether they are generated by established methods or by TagMo. The USDA regulatory definition of a GM crops is vague, and the EPA has a broad categorical exemption in its rules for GM crops with sequences from sexually compatible species (EPA, 2001).

Public failures will probably ensue if TagMo crops slip into the market under the radar without adequate oversight

The deletion of DNA sequences by TagMo to knock out a target gene is potentially of great agronomic value, as it could remove undesirable traits. For instance, it could eliminate anti-nutrients such as trypsin inhibitors in soybean that prevent the use of soy proteins by animals, or compounds that limit the value of a crop as an industrial material, such as ricin, which contaminates castor oil. Many mutagenesis methods yield similar products as TagMos. However, most conventional mutagenesis methods, including DNA alkylating agents or radioactivity, provide no precision in terms of the DNA sequences modified, and probably cause considerable collateral damage to the genome. It could be argued that TagMo is less likely to cause unpredicted genomic changes; however, additional research is required to better understand off-target effects—that is, unintended modification of other sites—by various TagMo platforms.

We propose that the discussion about how to regulate TagMo crops should be open, use public engagement and respect several criteria of oversight

Generating targeted gene knockouts (Fig 1C) does not directly involve transfer of foreign DNA, and such plants might seem to warrant an unregulated status. However, most TagMos use reagents such as engineered nucleases, which are created by rDNA methods. The resulting product might therefore be classified as a GM crop under the existing USDA definition for genetic engineering (USDA, 1997) since most TagMos are created by introducing a target-specific nuclease gene into plant cells. It is also possible to deliver rDNA-derived nucleases to cells as RNA or protein, and so foreign DNA would not need to be introduced into plants to achieve the desired mutagenic outcome. In such cases, the rDNA molecule itself never encounters a plant cell. More direction is required from regulatory agencies to stipulate the way in which rDNA can be used in the process of generating crops before the regulated status is triggered.

TagMo-derived crops that introduce alien transgenes or knock out native genes are similar to traditional GM crops or conventionally mutagenized plants, respectively, but TagMo crops that alter the DNA sequence of the target gene (Fig 1D) are more difficult to classify. For example, a GM plant could have a single nucleotide change that distinguishes it from its parent and that confers a new trait such as herbicide resistance. If such a subtle genetic alteration were attained by traditional mutagenesis or by screening for natural variation, the resulting plants would not be regulated. As discussed above, if rDNA techniques are used to create the single nucleotide TagMo, one could argue that it should be regulated. Regulation would then focus on the process rather than the product. If single nucleotide changes were exempt, would there be a threshold in the number of bases that can be modified before concerns are raised or regulatory scrutiny is triggered? Or would there be a difference in regulation if the gene replacement involves a sexually compatible or an incompatible species?

Most of this discussion has focused on the use of engineered nucleases such as meganucleases or zinc-finger nucleases to create TagMos. Oligonucleotide-mediated mutagenesis (OMM), however, is also used to modify plant genes (Breyer et al, 2009). OMM uses chemically synthesized oligonucleotides that are homologous to the target gene, except for the nucleotides to be changed. Breyer et al (2009) argue that OMM “should not be considered as using recombinant nucleic acid molecules” and that “OMM should be considered as a form of mutagenesis, a technique which is excluded from the scope of the EU regulation.” However, they admit that the resulting crops could be considered as GM organisms, according to EU regulatory definitions for biotechnology. They report that in the USA, OMM plants have been declared non-GM by the USDA, but it is unclear whether the non-GM distinction in the USA has regulatory implications. OMM is already being used to develop crops with herbicide tolerance, and so regulatory guidelines need to be clarified before market release.

In turning to address how TagMo-related oversight should proceed, two questions are central: how are decisions made and who is involved in making them? The analysis above illustrates that many fundamental decisions need to be made concerning the way in which TagMo-derived products will be regulated and, more broadly, what constitutes a GM organism for regulatory purposes. These decisions are inherently values-based in that views on how to regulate TagMo products differ on the basis of understanding of and attitudes towards agriculture, risk, nature and technology. Neglecting the values-based assumptions underlying these decisions can lead to poor decision-making, through misunderstanding the issues at hand, and public and stakeholder backlash resulting from disagreements over values.

Bozeman & Sarewitz (2005) consider this problem in a framework of ‘market failures’ and ‘public failures’. GM crops have exhibited both. Market failures are exemplified by the loss of trade with the EU owing to different regulatory standards and levels of caution (PIFB, 2006). Furthermore, there has been a decline in the number of GM crops approved for interstate movement in the USA since 2001. Public failures result from incongruence between actions by decision-makers and the values of the public. Public failures are exemplified by the anti-GM sentiment in the labelling of organic foods in the USA and court challenges to the biosafety review of GM crops by the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (McHughen & Smyth, 2008). These lawsuits have delayed approval of genetically engineered alfalfa and sugar beet, thus blurring the distinction between public and market failures. Public failures will probably ensue if TagMo crops slip into the market under the radar without adequate oversight.

The possibility of public failures with TagMo crops highlights the benefits of an anticipatory governance-based approach, and will help to ensure that the technology meets societal needs

Anticipatory governance is a framework with principles that are well suited to guiding TagMo-related oversight and to helping to avoid public failures. It challenges an understanding of technology development that downplays the importance of societal factors—such as implications for stakeholders and the environment—and argues that societal factors should inform technology development and governance from the start (Macnaghten et al, 2005).

Anticipatory governance uses three principles: foresight, integration of natural and social science research, and upstream public engagement (Karinen & Guston, 2010). The first two principles emphasize proactive engagement using interdisciplinary knowledge. Governance processes that use these principles include real-time technology assessment (Guston & Sarewitz, 2002) and upstream oversight assessment (Kuzma et al, 2008b). The third principle, upstream public engagement, involves stakeholders and the public in directing values-based assumptions within technology development and oversight (Wilsdon & Wills, 2004). Justifications for upstream public engagement are substantive (stakeholders and the public can provide information that improves decisions), instrumental (including stakeholders and the public in the decision-making process leads to more trusted decisions) and normative (citizens have a right to influence decisions about issues that affect them).

TagMo crop developers seem to be arguing for a ‘process-based’ exclusion of TagMo crops from regulatory oversight, without public knowledge of their development or ongoing regulatory communication. We propose that the discussion about how to regulate TagMo crops should be open, use public engagement and respect several criteria of oversight (Kuzma et al, 2008a). These criteria should include not only biosafety, but also broader impacts on human and ecological health and well-being, distribution of health impacts, transparency, treatment of intellectual property and confidential business information, economic costs and benefits, as well as public confidence and values.

We also propose that the CFRB should be a starting point for TagMo oversight. The various categories of TagMo require an approach that can discern and address the risks associated with each application. The CFRB allows for such flexibility. At the same time, the CFRB should improve public engagement and transparency, post-market monitoring and some aspects of technical risk assessment.

As we have argued, TagMo is on the verge of being broadly implemented to create crop varieties with new traits, and this raises many oversight questions. First, the way in which TagMo technologies will be classified and handled within the US regulatory system has yet to be determined. As these decisions are complex, values-based and have far-reaching implications, they should be made in a transparent way that draws on insights from the natural and social sciences, and involves stakeholders and the public. Second, as products derived from TagMo technologies will soon reach the marketplace, it is important to begin predicting and addressing potential regulatory challenges, to ensure that oversight systems are in place. The possibility of public failures with TagMo crops highlights the benefits of an anticipatory governance-based approach, and will help to ensure that the technology meets societal needs.

So far, the EU has emphasized governance approaches and stakeholder involvement in the regulation of new technologies more than the USA. However, if the USA can agree on a regulatory system for TagMo crops that is the result of open and transparent discussions with the public and stakeholders, it could take the lead and act as a model for similar regulation in the EU and globally. Before this can happen, a shift in US approaches to regulatory policy would be needed.

Jennifer Kuzma

Adam Kokotovich

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grant 0923827. The authors thank Professor D. Voytas for helpful technical input in the preparation of the manuscript and M. Christian for technical conversations during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bozeman B, Sarewitz D (2005) Public values and public failures in US science policy. Sci Public Pol 32: 119–136 [Google Scholar]

- Breyer D, Herman P, Brandenburger A, Gheysen G, Remaut E, Soumillion P, Van Doorsselaere J, Custers R, Pauwels K, Sneyers M (2009) Commentary: genetic modification through oligonucleotide-mediated mutagenesis. A GMO regulatory challenge? Environ Biosafety Res 8: 57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA (2001) Regulations under the Federal Fungicide, Insecticide, and Rodenticide Act for plant-incorporated protectants. Federal Register 66: 37772 [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Smith J, Yang M, Jones S, Djukanovic V, Nicholson MG, West A, Bidney D, Falco SC, Jantz D (2010) Heritable targeted mutagenesis in maize using a designed endonuclease. Plant J 61: 176–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guston DH, Sarewitz D (2002) Real-time technology assessment. Technol Soc 23: 93–109 [Google Scholar]

- Karinen R, Guston DH (2010) Toward anticipatory governance: the experience with nanotechnology. In Governing Future Technologies: Nanotechnology and the Rise of an Assessment Regime, Kaiser M, Kurath M, Maasen S, Rehmann-Sutter C (eds), pp 217–232. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Kuzma J, Meghani Z (2009) The public option. EMBO Rep 10: 1288–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzma J, Najmaie P, Larson J (2009) Evaluating oversight systems for emerging technologies: a case study of genetically engineered organisms. J Law Med Ethics 37: 546–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzma J, Paradise J, Ramachandran G, Kim J, Kokotovich A, Wolf SM (2008a) An integrated approach to oversight assessment for emerging technologies. Risk Analysis 28: 1197–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzma J, Romanchek J, Kokotovich A (2008b) Upstream oversight assessment for agrifood nanotechnology: a case studies approach. Risk Analysis 28: 1081–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnaghten P, Kearnes MB, Wynne B (2005) Nanotechnology, governance, and public deliberation: what role for the social sciences? Sci Commun 27: 268 [Google Scholar]

- Magana-Gomez J, de la Barca AMC (2009) Risk assessment of genetically modified crops for nutrition and health. Nutrition Rev 67: 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHughen A, Smyth S (2008) US regulatory system for genetically modified [genetically modified organism (GMO), rDNA or transgenic] crop cultivars. Plant Biotechnol 6: 2–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (1989) Field Testing Genetically Modified Organisms: Framework for Decisions. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2000) Genetically Modified Pest-Protected Plants: Science and Regulation. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2002) Environmental Effects of Transgenic Plants. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (2004) Safety of Genetically Engineered Foods. Wasington, DC, USA: National Academies Press [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Science and Technology Policy (1986) Coordinated framework for the regulation of biotechnology. Federal Register 51: 23302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIFB (2006) Agricultural Biotechnology Information Disclosure: Accommodating Conflicting Interests Within Public Access Norms. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Pew Initiative on Food and Biotechnology [Google Scholar]

- Pollack A (2011) US says farmers may grow engineered sugar beets. The New York Times 4 Feb [Google Scholar]

- Russell AW, Sparrow R (2008) The case for regulating intragenic GMOs. J Agr Environ Ethics 21: 153–181 [Google Scholar]

- Schouten HJ, Krens FA, Jacobsen E (2006) Cisgenic plants are similar to traditionally bred plants. EMBO Rep 7: 750–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla VK, Doyon Y, Miller JC, DeKelver RC, Moehle EA, Worden SE, Mitchell JC, Arnold NL, Gopalan S, Meng X (2009) Precise genome modification in the crop species Zea mays using zinc-finger nucleases. Nature 459: 437–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PB (2007) Food Biotechnology in Ethical Perspective. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Townsend JA, Wright DA, Winfrey RJ, Fu F, Maeder ML, Joung JK, Voytas DF (2009) High-frequency modification of plant genes using engineered zinc-finger nucleases. Nature 459: 442–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA (1997) Introduction of Organisms and Products Altered or Produced Through Genetic Engineering which are Plant Pests or Which There is a Reason to Believe are Plant Pests. 7 CFR 340. http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov [Google Scholar]

- USDA (2010) Adoption of Genetically Engineered Crops in the US. http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/BiotechCrops [Google Scholar]

- Voosen P (2011) USDA's alfalfa decision postpones reckoning on biotech crops. The New York Times 28 Jan [Google Scholar]

- Weinthal D, Tovkach A, Zeevi V, Tzfira T (2010) Genome editing in plant cells by zinc finger nucleases. Trends Plant Sci 15: 308–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsdon J, Wills R (2004) See-through science: why public engagement needs to move upstream. London, UK: Demos. www.demos.co.uk [Google Scholar]