Abstract

Adolescent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination uptake, as a means of cervical cancer prevention, remains suboptimal with significant racial disparity. A survey study of mothers already engaging in their own cancer screening, at a predominantly black urban site and a predominantly white suburban site, finds that a majority of mothers surveyed support hypothetical mandates for adolescent HPV vaccination three years after the introduction of these vaccines. Enactment of state laws may represent an efficient means to improve HPV vaccination in adolescent daughters of these mothers. Nevertheless, in a sizable minority, maternal perceptions of the HPV vaccine may hinder adherence to these vaccination laws. In these women, tailored interventions directed at these perceptions may be required.

Key words: mandates, maternal barriers, health behavior, legislation, teachable moment

The recent introduction of vaccines against the two most common types of oncogenic human papillomaviruses (HPV) represents an opportunity to reduce acquisition of this infection in the adolescent population and future cancer risk. National data have demonstrated an encouraging level of vaccine use in adolescents ages 13–17.1 As of 2008, 37.2% of females in this age range had received at least one dose of a three-dose HPV vaccine series, and 17.9% had completed the series. However, utilization varied significantly by state. Past research has demonstrated that mandating vaccination coverage for school attendance can be highly effective at increasing vaccination levels among children and adolescents.2

Legislative action regarding adolescent HPV vaccination has captured the attention of parents and the general public,3 the ethics of which has been considered by Zimmerman.4 Introduction of legislation has met with a variety of obstacles at the state level where these laws are being considered.5,6 Immediately after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended the quadrivalent HPV vaccine, a national poll on children's health queried parental views on school mandates for HPV vaccination. In this poll, 44% of respondents supported mandatory HPV vaccination compared to 68% support for the adolescent vaccine for tetanus, diphtheria and whooping cough.7 More recent studies have demonstrated a similar level of support among both parents and physicians for mandating HPV vaccination.8–10

Increasing adolescent HPV vaccination is particularly important as the rates of cervical carcinoma-in-situ, or CIN3, have risen sharply in the under-20-year-old group.11 Although cervical cancer screening remains the primary means of cervical cancer prevention, HPV vaccination enhances cervical cancer screening to further protect against the development of CIN3 and cervical cancer. Furthermore, in populations where cervical cancer screening may be suboptimal, or where disparities in cervical cancer outcomes exist, communities may consider HPV vaccine mandates to increase vaccine coverage among at-risk populations.

We previously demonstrated that even among adolescent daughters of mothers already completing their own cancer preventive services, HPV vaccine uptake remains suboptimal with significant racial differences.12 To assess the potential impact of introducing adolescent HPV vaccination mandates three years after the CDC's recommendation, we evaluated the maternal intent to follow HPV vaccination laws among a sample of mothers completing breast and cervical cancer screening.

Results

We previously described our survey of women attending breast and cervical cancer screening at two geographically, racially and economically distinct sites to determine the proportion of women who were mothers of adolescent daughters who are age-eligible for HPV vaccination.13 In this population, our response rate was 31.2% of surveys mailed (28% (n = 556/2,000) in the urban and 38% (n = 381/1,000) in the suburban sites).13 Of the 937 respondents, 232 comprised mothers or primary caretakers of adolescent females aged 9–17; the socio-demographic characteristics of the study population have previously been reported in reference 13. Briefly, 21% of mothers overall were black and 3% were Hispanic. Nearly all mothers (99%) reported that their daughters had some form of health insurance.

Maternal intent to follow HPV vaccine laws.

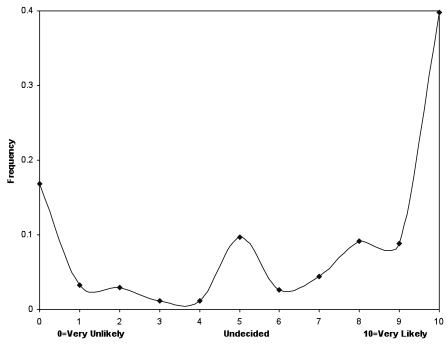

Using the 11-point scale, the distribution of maternal intent to follow a hypothetical law mandating adolescent HPV vaccination appeared to cluster in three modes (see Fig. 1). Therefore, the scale was collapsed into three groups: low intent (22.2%, representing 0–3 on the scale), undecided (14.3%, representing 4–6 on the scale) and high intent (63.5%, representing 7–10 on the scale). When limiting the analysis to women with daughters ages 11–12, the group for which routine vaccination is recommended, 29.3% of mothers expressed low intent to follow a hypothetical mandate; 12.0% were undecided; and 58.7% expressed a high intent.

Figure 1.

Maternal intent to follow a hypothetical adolescent HPV vaccination mandate.

Predictors of maternal intent to follow HPV vaccine laws.

We collapsed the outcome variable into two groups, low or undecided intent to vaccinate (scale response 0–6) and high intent to vaccinate (scale response 7–10). In univariable analysis of demographic characteristics (Table 1), none of the maternal nor adolescent demographic characteristics were associated with maternal intent to follow HPV vaccine laws.

Table 1.

Correlates of maternal intent to comply with a hypothetical law mandating adolescent HPV vaccination

| Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||||

| Unadjusted Odds Ratios | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted Odds Ratios | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Maternal Demographics and Health History | ||||||

| Black race | 0.81 | 0.48–1.37 | 0.438 | 1.03 | 0.45–2.36 | 0.951 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.96–1.07 | 0.661 | 1.28 | 0.56–2.93 | 0.553 |

| Household income below $40,000 | 1.70 | 0.86–3.33 | 0.127 | - | ||

| College graduate or above | 0.91 | 0.54–1.56 | 0.737 | - | ||

| Married or in a non-marriage partnership | 1.08 | 0.61–1.92 | 0.781 | - | ||

| Urban site1 | 1.47 | 0.91–2.38 | 0.119 | 1.62 | 0.76–3.44 | 0.212 |

| Cervical cancer screening2 | 0.84 | 0.51–1.40 | 0.511 | 0.58 | 0.30–1.13 | 0.109 |

| History of any cervical problem (abnormal Pap smear, colposcopy or cervical cancer) | 1.36 | 0.82–2.26 | 0.239 | - | ||

| Adolescent Demographics | ||||||

| Age ≤12 | 0.65 | 0.38–1.10 | 0.110 | 0.88 | 0.43–1.80 | 0.722 |

| Private Insurance | 0.82 | 0.44–1.51 | 0.527 | 0.60 | 0.05–6.73 | 0.676 |

| Maternal Attitudinal Scales and Items | ||||||

| Safety concerns | 0.24 | 0.15–0.40 | <0.001 | 0.44 | 0.25–0.77 | 0.004 |

| Vaccine benefits | 6.21 | 3.73–10.4 | <0.001 | 2.98 | 1.62–5.49 | 0.001 |

| Vaccine barriers | 1.07 | 0.87–1.33 | 0.513 | - | ||

| Knowledge index | 3.38 | 1.39–8.20 | 0.007 | 2.19 | 0.59–8.08 | 0.240 |

| My daughter is too young to be vaccinated against HPV | 0.52 | 0.42–0.65 | <0.001 | 0.72 | 0.54–0.98 | 0.035 |

| My daughter's medical provider recommends the vaccine against HPV | 1.67 | 1.26–2.22 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 0.84–1.67 | 0.333 |

| My daughter is currently sexually active or will become sexually active soon. | 2.44 | 1.16–5.10 | 0.019 | 1.07 | 0.39–2.98 | 0.890 |

| My religious beliefs influence my decision to vaccinate her against HPV | 0.62 | 0.48–0.80 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.59–1.27 | 0.466 |

| My moral beliefs influence my decision to vaccinate her against HPV | 0.79 | 0.65–0.96 | 0.016 | 1.01 | 0.75–1.34 | 0.962 |

Compared to the suburban site.

Compared to breast cancer screening.

In univariable analyses of individual-level knowledge and attitudes, higher scores on the knowledge index and vaccination benefits scale were significantly associated with higher odds of maternal intent to follow a HPV vaccine mandate. Higher scores on the safety concern scale were associated a lower odds of intention to comply as did individual items assessing maternal belief that her daughter was too young to be vaccinated and religious and moral beliefs. In contrast, maternal belief that her daughter's medical provider recommends vaccination and that her daughter is currently sexually active or soon will be were both associated with higher odds of maternal intent to comply with a vaccine mandate (Table 1).

In the multivariable model, only three independent variables remained significant predictors of maternal intent to follow a hypothetical HPV vaccine law. High safety concern scores [adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.4, 95% CI 0.25–0.77] and a perception that her daughter was too young for vaccination (adjusted OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.54–0.98) were associated with lower probability of maternal intent to comply. High vaccine benefits scale scores (AOR 2.98, 95% CI 1.62–5.49) were associated with higher maternal intent to comply.

Discussion

In mothers who already undergo their own cancer preventive services, a majority expressed a high intent to comply with a hypothethical law mandating adolescent HPV vaccination for school attendance. In the current absence of such a mandate, in the same population, we previously demonstrated that HPV vaccination rates are low with significant racial disparity.12 Strategies directed at vaccination policy have been proposed as a means to achieve the high rates of HPV vaccine coverage in adolescents recommended by the Healthy People 2010 report,14 similar to other vaccines currently required for school-aged children. Our work suggests that a law mandating adolescent HPV vaccination would result in about 60% of mothers will eligible children intending to comply with the law. Further, that intention to comply with such a mandate might assist in mitigating the racial disparities that have been reported for HPV vaccine use among adolescent females.12,15

HPV vaccination policy.

In 2007, a national survey of parents demonstrated that the majority were not in favor of state mandates for HPV vaccination.7 A study in 2008 by Horn et al. conducted in a convenience sample of parents in Georgia and South Carolina yielded similar results.8,9 Although we did not explicitly query support for HPV vaccination mandates, our study conducted two years later appears to demonstrate a shift in attitude regarding such a mandate where a high intent to comply could be interpreted as a favorable attitude, at least among mothers who complete their own cancer preventive care. This discrepancy between our study and previous studies in reference 7, could be related to the populations addressed—mothers in our study who were undergoing cancer screening visits may have an inherently higher interest in cervical cancer prevention (via HPV vaccination) among their daughter than mothers who do not undergo such visits. Timing of our survey four years after introduction of the HPV vaccine and regional variation in parental attitudes may have also influenced apparent differences in opinions of vaccine mandates. Nevertheless, even among the mothers in our sample, a sizable minority remained undecided or expressed a low intention to comply with a hypothetical law for adolescent HPV vaccination. This result suggests that school mandates for HPV vaccination will not be a complete panacea for increasing HPV vaccination rates among adolescents, even among the subgroups whose mothers are actively involved themselves in cancer prevention activities.

No maternal demographic factors were found to be associated with maternal intent, contrary to previous work demonstrating lower HPV vaccine use in adolescent daughters of black mothers.12 Similar individual beliefs such as a belief that her daughter was too young, perceived benefit to vaccination and vaccine safety concerns also influenced both maternal intent and actual vaccine use.12 These findings are consistent with previous studies that examined these issues among diverse populations. The consistency of these results suggests that these issues may be key target areas for future health communication and policy interventions to improve maternal willingness for HPV vaccination of their daughters.15–18

Historically, mandates have been shown to be an effective policy to improve immunization rates, and likely have contributed to the decrease in disparities in utilization that have been achieved for many vaccines.19 Our results suggest that mandates for HPV vaccines may improve adolescent HPV vaccination rates as 63% of the mothers in our study indicated they would comply with such a policy. However, in the remaining mothers, tailored maternal education addressing individual-level beliefs may be needed to overcome these mothers' hesitation for HPV vaccination in their adolescent daughters.

One limitation of our study is 31% response rate. Despite inviting 3,000 women to participate and offering incentives for both reading and completing the survey, our response rate remained low. However, our results are consistent with several previous studies.15–18 The wording of our question asking mothers how “likely they are to follow [an adolescent HPV vaccination] law” without noting an opt-out clause similar to existing vaccine mandates may have biased toward a higher maternal intent-to-vaccinate. Additionally, we queried mothers about a hypothetical law for HPV vaccination. Reported intention to adhere to a hypothetical mandate may not reflect actual behavior should a law be enacted. However, a previous study that found lower intention to comply with an HPV vaccine school mandate also assessed opinions about a mandate that was hypothetical.7 Our results therefore suggest that public opinion may have changed over the two year time period between our study and that previously reported. Given that two states have actually implemented HPV vaccine mandates for girls entering middle school,20 the adherence with such a policy will be able to be measured directly in the near future.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at two geographically, racially and economically distinct sites; one serving a mostly black (54.1%) urban inner-city population (referred to as the urban site) and another serving a mostly white (87.5%) suburban population (referred to as the suburban site). Women 25–55 years old who attended a cancer screening visit received a survey by mail within 6–18 months after their screening. The mail-based self-administered written survey assessed several constructs potentially related to HPV uptake, including demographics, knowledge of and experience with HPV and HPV-related diseases, and individual-level perceptions such as perceived benefits, barriers and safety concerns about adolescent HPV vaccination and intention to comply with a hypothetical mandate for adolescent HPV vaccination. The study sites and survey sampling protocol13 have previously been described. This study was approved by the University of Michigan and University of Chicago Institutional Review Boards.

Survey instrument.

A copy of the instrument will be provided by request.

Sociodemographic characteristics. Sociodemographic characteristics were self-reported in reference 13, and included the age of the study participant, age and number of children in the family, maternal race/ethnicity, education level, annual income, marital status and the insurance status and type of the eldest adolescent daughter of the household.

Knowledge. Knowledge was assessed using questions from a previous study on parental acceptance of HPV vaccination for their adolescent daughter.21 Using a scale of 7 true-false questions, a knowledge index score was calculated by averaging the number of correct answers over the number of knowledge questions answered.

Individual-level perceptions. Brewer et al.'s recent systematic review in reference 22, demonstrated that parental beliefs, such as perceptions of vaccine benefits and barriers, conforming to the Health Belief Model constructs were associated with parental acceptance of HPV vaccination for his or her adolescent daughter. Dempsey et al.21 developed and tested scales and items describing these constructs in a randomized trial testing the effect of print educational material about the HPV vaccine on parental acceptance of adolescent HPV vaccination in parents of adolescent daughters. We used these scales and items to describe the beliefs among mothers of adolescent daughters who completed breast or cervical cancer screening and the association between these beliefs and maternal intention to comply with a hypothetical mandate on adolescent HPV vaccination.

We evaluated maternal perceptions of her adolescent's susceptibility to HPV, benefits, barriers and safety concerns about adolescent HPV vaccination. Individual perception factors, derived from a previous study on parental acceptance of HPV vaccination for their adolescent daughter included mothers' perceived benefits and barriers to vaccination and vaccine safety concerns. Perceived benefits and barriers to HPV vaccination assessed on a five-point scale (1—strongly agree to 5—disagree). Perceived benefits was measured with four items (α = 0.76) regarding maternal perceptions that HPV vaccination can protect her daughter from genital warts and cervical cancer; that the vaccine could protect her daughter's health and that the vaccine could benefit both men and women. Perceived barriers were measured with two items (α = 0.90) related to maternal perceptions of vaccination discomfort. Safety concerns (α = 0.82) of the mother were measured with five items (for example, “There is not enough information about the long term effects of a vaccine against HPV).”

Outcome measure.

The primary outcome measured in this study was maternally-reported intent to follow a hypothetical law that required HPV vaccination for her oldest adolescent daughter. The outcome was measured using an 11-point Likert-type scale (0—very unlikely, 10—very likely). The survey item on maternal intent to comply with a hypothetical adolescent HPV vaccination mandate and the introduction to the survey section preceding the survey item are as follows:

In the following section, we are interested in your opinions and knowledge of vaccines against HPV.

When we refer to your daughter, we mean your oldest daughter who is between 9–17 years old. If a law were passed that required your daughter to be Conclusion vaccinated, how likely would you be to follow this law?

Statistical analysis.

After descriptive statistics were calculated for the primary outcome, the association with various maternal characteristics was assessed using chi-square tests. To preserve statistical power, we collapsed maternal race to black or non-black race. Similarly, we collapsed household income to ≤$40,000 or above and maternal education to college graduate or higher vs. not. Demographic, individual-level perception scale variables with good internal reliability (α coefficient ≥0.70) and individual items were assessed as predictors of maternal intent to follow HPV vaccination laws using univariable logistic regression. Variables found to be statistically significantly associated (p < 0.05) with maternal intent to follow HPV vaccination laws were included in a multivariable logistic regression model to determine independent predictors of this outcome. In addition, ethnicity, study site, type of cancer screening visit, daughter age and adolescent insurance status were also included in the multivariable model as these were hypothesized a priori to be influential on maternal intent to comply with a hypothetical mandate for adolescent HPV vaccination. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 10.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Conclusion

Primary prevention of cervical and other HPV-associated cancers via vaccination is an important breakthrough in women's health. Enactment of state laws that require HPV vaccination for school attendance may represent a means to improve adolescent HPV vaccination. Nevertheless, even among mothers who have an active interest in cancer prevention, as demonstrated by their participation in cervical or breast cancer screening activities, a significant minority indicated that the were undecided or would not comply with such a policy. For these mothers with more significant hesitation to having their adolescent daughter vaccinated against HPV, tailored interventions directed at these mothers' attitudes may be required.

Acknowledgements

Funded in part by NIH/NCI K07 CA108664 and R21 CA133333 (R.C.C.), Michigan BIRCWH K12 HD001438 (A.F.D.), NIH/NCI CA120040 (D.A.P.), AHRQ K08 (V.K.D.).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.National, State and Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years—United States 2008. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58:997–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson TR, Fishbein DB, Ellis PA, Edlavitch SA. The impact of a school entry law on adolescent immunization rates. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gostin LO, DeAngelis CD. Mandatory HPV vaccination: public health vs. private wealth. JAMA. 2007;297:1921–1923. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.17.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman RK. Ethical analysis of HPV vaccine policy options. Vaccine. 2006;24:4812–4820. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Udesky L. Push to mandate HPV vaccine triggers backlash in USA. Lancet. 2007;369:979–980. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wynia MK. Public health, public trust and lobbying. Am J Bioeth. 2007;7:4–7. doi: 10.1080/15265160701429599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health NPoCs, author. Majority of US parents not in favor of state HPV vaccine mandates. CS Mott Children's Hospital. 2007;1 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferris D, Horn L, Waller JL. Parental acceptance of a mandatory human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination program. J Am Board Fam Med. 23:220–229. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.090091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horn L, Howard C, Waller J, Ferris DG. Opinions of parents about school-entry mandates for the human papillomavirus vaccine. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 14:43–48. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3181b0fad4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn JA, Cooper HP, Vadaparampil ST, Pence BC, Weinberg AD, LoCoco SJ, Rosenthal SL. Human papillomavirus vaccine recommendations and agreement with mandated human papillomavirus vaccination for 11-to-12-year-old girls: a statewide survey of Texas physicians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2325–2332. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Copeland G, Datta SD, Spivak G, Garvin AD, Cote ML. Total burden and incidence of in situ and invasive cervical carcinoma in Michigan 1985–2003. Cancer. 2008;113:2946–2954. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlos RDA, Patel D, Ruffin M, Dalton V. Maternal cultural barriers correlate with adolescent HPV vaccine use. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:895. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlos RCRM, Patel DA, Straus CM, Dalton VK. Do mothers completing breast and cervical cancer screening have adolescent daughters at the appropriate age for HPV vaccination. J Women's Health. 19:2271–2275. [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDCUSCfDCaP, author. Immunization and Infectious Disease. 2002;14 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dempsey AF, Abraham LM, Dalton V, Ruffin M. Understanding the reasons why mothers do or do not have their adolescent daughters vaccinated against human papillomavirus. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:531–538. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chao C, Velicer C, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ. Correlates for completion of 3-dose regimen of HPV vaccine in female members of a managed care organization. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:864–870. doi: 10.4065/84.10.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Constantine NA, Jerman P. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination among Californian parents of daughters: a representative statewide analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn JA, Ding L, Huang B, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, Frazier AL. Mothers' intention for their daughters and themselves to receive the human papillomavirus vaccine: a national study of nurses. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1439–1445. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Z, Luman ET. Progress toward eliminating disparities in vaccination coverage among US children 2000–2008. Am J Prev Med. 38:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.HPV Vaccine Legislation 2009–2010. National Conference of State Legislators 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dempsey AF, Zimet GD, Davis RL, Koutsky L. Factors that are associated with parental acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccines: a randomized intervention study of written information about HPV. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1486–1493. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.