Abstract

In fission yeast, replication fork arrest activates the replication checkpoint effector kinase Cds1Chk2/Rad53 through the Rad3ATR/Mec1-Mrc1Claspin pathway. Hsk1, the Cdc7 homolog of fission yeast required for efficient initiation of DNA replication, is also required for Cds1 activation. Hsk1 kinase activity is required for induction and maintenance of Mrc1 hyperphosphorylation, which is induced by replication fork block and mediated by Rad3. Rad3 kinase activity does not change in an hsk1 temperature-sensitive mutant, and Hsk1 kinase activity is not affected by rad3 mutation. Hsk1 kinase vigorously phosphorylates Mrc1 in vitro, predominantly at non-SQ/TQ sites, but this phosphorylation does not seem to affect the Rad3 action on Mrc1. Interestingly, the replication stress-induced activation of Cds1 and hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 is almost completely abrogated in an initiation-defective mutant of cdc45, but not significantly in an mcm2 or polε mutant. These results suggest that Hsk1-mediated loading of Cdc45 onto replication origins may play important roles in replication stress-induced checkpoint.

Key words: Cdc7, Cdc45, checkpoint, DNA replication, Mrc1

Introduction

1The process of DNA replication is strictly monitored, and unscheduled stalling of the replication fork is efficiently detected and dealt with to suspend the cell cycle, repair DNA lesions, if any, and to ultimately restart replication. This process, called replication checkpoint, is evolutionarily conserved, and plays crucial roles in the maintenance of genome integrity.1–7

Checkpoint signaling involves a series of conserved factors that transduce the fork arrest/DNA damage signals to DNA repair, cell cycle, cell death or senescence machinery. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the initial detection of stalled replication forks involves Rad3ATR-Rad26ATRIP kinase, the Rad17-RFC clamp loader protein complex and the Rad9-Hus1-Rad1 (9-1-1) checkpoint clamp protein complex.8 The Rad3ATR-Rad26ATRIP kinase is recruited to the stalled fork via RPA and Rad17 protein, which may bind to the exposed single-stranded DNA. Rad3 activates the checkpoint effector kinase Cds1 by a mechanism that requires mediator/adaptor protein Mrc1 (related to mammalian Claspin). In S. pombe, the sensor kinase Rad3 phosphorylates a cluster of SQ/TQ motifs in the middle of Mrc1. The phospho-SQ/TQ cluster on Mrc1 is thought to recruit Cds1 to stalled replication forks by a phospho-dependent interaction with the forkhead-associated (FHA) domain of Cds1. Cds1 is then phosphorylated by Rad3 at Thr11 and the phosphorylated Cds1 molecules dimerize by two identical intermolecular interactions between phosphorylated Thr11 and the FHA domain. Dimerization promotes autophosphorylation and its activation.9,10 Finally, the effector kinase mediates the cell cycle arrest and other signals, a part of which restrains the progression of S phase, most notably by inhibiting firing of late origins and slowing the fork rate. A study in budding yeast suggested that the level of checkpoint kinase activation correlates with the numbers of pre-Replication Complex (preRC) structures formed during G1.11 It has been reported that primed, single-stranded DNA is sufficient to activate checkpoint in Xenopus egg extracts, and more recently, it was suggested that continued synthesis of primer RNAs at the stalled fork stimulates checkpoint activation.12 However, the precise requirements of the fork structures for checkpoint activation have not been clarified.

Cdc7 kinase is a conserved serine-threonine kinase that plays an important role in initiation of DNA replication.13–15 Cdc7 in a complex with its activation subunit Dbf4 phosphorylates Mcm subunits in the prereplicative complex. This facilitates association of Cdc45 and other replisome proteins to assemble active replication forks.16–18 Recent studies have suggested diverse roles of Cdc7 in regulation of chromosome dynamics including DNA replication checkpoint.

We previously reported that Hsk1/Cdc7 kinase is required for checkpoint kinase activation induced by replication fork stress in fission yeast and human cells.19,20 In this communication, we have analyzed the roles of Hsk1 kinase and other replication factors in the activation of the replication checkpoint in fission yeast. We show that Hsk1 kinase activity is required for induction and maintenance of hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1. Furthermore, among the preRC and replication fork components examined, Cdc45 was shown to be essential for checkpoint activation. We will discuss the possibility that the loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin may be a critical signal that ensures sufficient activation of the checkpoint signal.

Results

Hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 induced by replication stress is eliminated in hsk1-89.

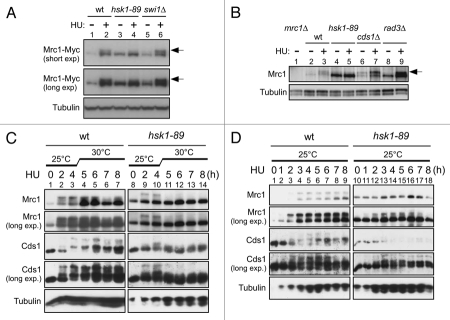

Treatment of cells with HU or aphidicolin induces checkpoint responses. In fission yeast, initial activation of Rad3-Rad26 is followed by Cds1 kinase activation through Mrc1 protein.1,21,22 In this process, Mrc1 is hyperphosphorylated,21–23 which can be detected as mobility-shifted bands on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A, lane 2; B, lane 3). Phosphatase treatment confirmed that this mobility-shift is due to phosphorylation (Sup. Fig. 1).23

Figure 1.

HU-induced hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 is impaired in hsk1-89. (A and B) The whole cell extracts prepared from the indicated cells were analyzed by western blotting using anti-Myc (A), anti-Mrc1 (B) and anti-α-tubulin (A and B) antibodies. After addition of 15 mM HU (A) or 25 mM HU (B) to the cultures grown at 25°C, the cells were kept growing at 25°C for 4 hrs (A) or at 30°C (non-permissive for hsk1-89) for 3 hrs (B). Arrows indicate phosphorylated forms of Mrc1 protein. (A) Lanes 1 and 2, KT2791; lanes 3 and 4, MS346; lanes 5 and 6, MS401. (B) Lane 1, MS252; lanes 2 and 3, YM71; lanes 4 and 5, KO147; lanes 7 and 8, NI485. Slight increase of hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 in swi1Δ cells may be due to increased fork damages in this strain. (C and D) The whole cell extracts prepared from YM71 (hsk1+, lanes 1–7) and KO147 (hsk1-89, lanes 8–14) were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies indicated. After addition of 15 mM HU to the cells grown at 25°C, they were shifted to 30°C for 4 hrs (C) or kept at 25°C throughout the experiment (D). In (C and D), the samples were analyzed on 7.5% SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide:bisacrylamide = 99:1) containing 25 µM Phos-tag (1st, 2nd and 5th parts) or on 6.5% SDS-PAGE (99:1) containing 25 µM Phos-tag (3rd and 4th parts).

We previously reported that Cds1 kinase activation by HU depends on Hsk1 function.20 Therefore, we have examined the effect of hsk1-89 mutation on the hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1. At the permissive temperature (25°C), the extent of HU-induced hyperphosphorylation was reduced (Fig. 1A, lane 4), and it was almost completely eliminated at the non-permissive temperature (30°C) in hsk1-89 (Fig. 1B, lane 5). The mobility-shift was only partially lost in rad3Δ cells (Fig. 1B, lane 9),23 as compared to hsk1-89 cells. It is known that the residual phosphorylation depends on Tel1.23

Since it was previously reported that the extent of replication checkpoint may depend on the number of the preRC assembled in G1 phase,11,24 the reduced initiation efficiency in hsk1-89 may indirectly affect checkpoint response. Therefore, we first activated the checkpoint in hsk1-89 at the permissive temperature and then raised the temperature to the non-permissive temperature. Phosphorylation of Mrc1 was detected, albeit at a reduced level compared to the wild-type cells, at 4 hrs after addition of HU (Fig. 1C, lane 10), at which time temperature was raised to the non-permissive temperature (30°C). At 1 hr after the temperature shift (5 hrs after HU addition), the mobility-shift was almost completely lost in hsk1-89 cells (Fig. 1C, lane 11), while that in the wild-type strain was maintained until 8 hrs after HU addition (Fig. 1C, lane 7). Under this condition, Cds1 activation, as revealed by the mobility-shift on a Phosgel, was detected at 2 hrs after the HU addition (Fig. 1C, lane 2), and was maintained until 8 hrs after shift to 30°C in the wild-type cells (Fig. 1C, lane 7), while that in hsk1-89 cells mostly disappeared at 5 hrs after HU addition (1 hr after the temperature shift; Fig. 1C, lane 11). In contrast, at 25°C, phosphorylation of Mrc1 stayed until 7 hrs after HU addition and the hyperphosphorylated form of Cds1 was also detected for 8 hrs even in hsk1-89 (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that Hsk1 kinase activity is required for maintaining the hyperphosphorylated state of Mrc1. Since the replication forks were present in amount sufficient to activate the checkpoint to a certain extent at the time of temperature shift, this result suggests that Hsk1 is directly required for maintenance of hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 in the presence of replication stress. Alternatively, the proper replication fork structures may not be maintained in hsk1-89 cells at a non-permissive temperature, thus inactivating the checkpoint activation.

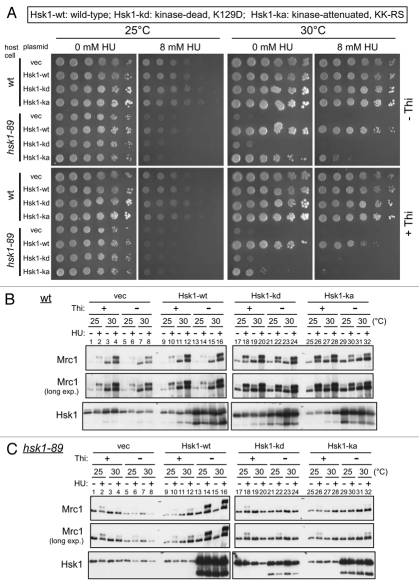

Phosphorylation of Mrc1 in response to fork arrest requires the kinase activity of Hsk1.

Kinase activity of Hsk1 is essential for viability and for initiation of DNA replication under normal conditions. We examined whether the kinase activity of Hsk1 is required for HU-induced phosphorylation of Mrc1. We introduced plasmids expressing mutant forms of Hsk1 in which the kinase activity is inactivated (Hsk1-kd; kinase.dead, K129D) or attenuated [Hsk1-ka; kinase-attenuated, KK-RS (= K129R-K130S)]25 as well as wild-type Hsk1 into hsk1-89 cells and examined the phosphorylation of Mrc1 at the nonpermissive temperature (30°C). Although wild-type Hsk1 restored the growth at 30°C and HU-resistance in hsk1-89, Hsk1-kd did not do so. Hsk1-ka restored the growth of hsk1-89 at 30°C only after overproduction (Fig. 2A). However, the strain was still sensitive to 8 mM HU under this condition, suggesting that the replication is not completely restored. Under this condition, the hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 in hsk1-89 was restored by Hsk1 but not by Hsk1-kd or Hsk1-ka (Fig. 2C, lanes 20, 24, 28 and 32), suggesting that Hsk1 kinase activity is strictly required for the checkpoint induction. It is also interesting to note that the requirement of the kinase activity may be more stringent for HU-resistance and HU-induced hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 than for normal growth. Although pREP81-hsk1+ can restore the growth of hsk1-89 at 30°C when cells are grown in the presence of thiamine that represses hsk1+ expression from the thiamine-repressible nmt81 promoter,26 this level of expression cannot completely restore the HU resistance and hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 in hsk1-89 cells under the same condition (Fig. 2C, lane 12). Hsk1-ka can restore the growth of hsk1-89 at 30°C in the absence of thiamine, but it is still partially sensitive to HU and Mrc1 hyperphosphorylation is not restored under the same condition (Fig. 2C, lane 12). These results suggest that there are different requirements for Hsk1 activity in the initiation of DNA replication and in cellular responses to replication stress.

Figure 2.

Wild-type Hsk1 but not kinase-negative or kinase-attenuated Hsk1 restores HU resistance or hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 in hsk1-89. pREP 81 (Vec), pREP 81-Hsk1 wild-type (Hsk1wt), pREP 81-Hsk1 K129D (Hsk1-kd; kinase-dead) or pREP 81-Hsk1 KK129,130RS[KK-RS] (Hsk1-ka; kinase-attenuated) was transformed into hsk1+ (YM71) or hsk1-89 (KO147) cells. (A) Five-fold serial dilutions of exponentially growing cells harboring each plasmid indicated were plated on EMM supplemented with Uracil (EMMura) agar medium with or without thiamine and incubated at 25 or 30°C for seven days as indicated. One set of plates (right part for each temperature) contained 8 mM HU. (B and C) The same set of cells were grown at 25°C in EMMura with or without thiamine as indicated. For HU-treatment at 25°C, 15 mM HU was added to the half of the culture and the other half was non-treated. The incubation was continued for 4 hrs at 25°C. For HU-treatment at 30°C, 25 mM HU was added to the half of the culture and the other half was non-treated. The incubation was continued for 3 hrs at 30°C. The whole cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by western blotting to detect Mrc1 and Hsk1 proteins.

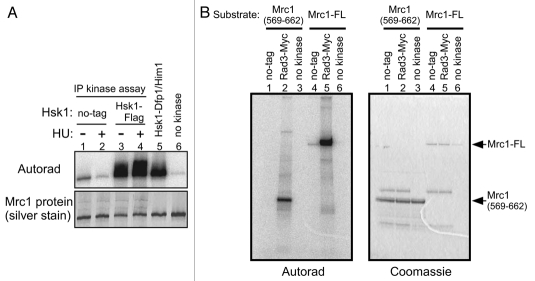

Assays of endogenous kinase activities of Rad3, Hsk1 and Cds1.

To biochemically dissect the relationships among Rad3, Hsk1 and Cds1, we adapted or developed assay systems to measure their kinase activities. Hsk1 kinase assays were conducted by utilizing a Flag-tagged Hsk1 strain. Purified Mrc1 protein was vigorously phosphorylated by the anti-Flag antibody immunoprecipitate from the tagged strain (Fig. 3A, lanes 3 and 4) but not by that from the non-tagged strain (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 and 2). Rad3 kinase assays were similarly developed by utilizing a Myc-tagged Rad3 strain. The anti-Myc antibody immunoprecipitate from the tagged strain but not from a non-tagged strain phosphorylated the full-length Mrc1 protein or GST-Mrc1 (569–662) containing the SQ/TQ clusters of Mrc1 (Fig. 3B, lanes 1, 2, 4 and 5). Phosphorylation of Mrc1 by Rad3 was also detected by the phosphorylated SQ/TQ antibody (Sup. Fig. 4B). We found that 8 mM Mn2+ stimulated Rad3 kinase activity while suppressing nonspecific kinase activities. Cds1 kinase was measured by reactions in a crude extract using the GST-Wee1 N-terminal polypeptide (1–70; GST-Wee170) as a substrate (Sup. Fig. 2),27 or by phosphorylation assays using anti-Cds1 immunoprecipitates (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Kinase assays of endogenous Hsk1 and Rad3 kinase activities. Kinase assays were conducted as described in “Experimental Procedures” with anti-Flag antibody (A) or anti-Myc antibody (B) immunoprecipitates. (A) Vigorous phosphorylation of Mrc1 is detected with immunoprecipitated Flag-Hsk1 protein. Extracts were prepared from non-tagged (lanes 1 and 2, YM71) or from Flag-tagged Hsk1 strain (lanes 3 and 4, MS335) grown at 30°C. Cells were non-treated (lanes 1 and 3) or incubated with 12 mM HU for 2 hrs (lanes 2 and 4). Lane 5, reaction with purified Hsk1-Dfp1/Him1 complex; lane 6, reaction without kinase. Upper, autoradiogram; lower, silver staining. (B) Phosphorylation of GST-Mrc1 (569–662 aa) polypeptide (lanes 1–3) or Mrc1 full-length polypeptide (lanes 4–6) by the immunoprecipitated Rad3-Myc protein. Extracts were prepared from non-tagged (lanes 1 and 4, YM71) or Myc-tagged Rad3 strain (lanes 2 and 5, SH5142). Lanes 3 and 6, reactions without kinase. Left, autoradiogram; right, CBB staining.

Since the hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 partially depends on Rad3 kinase, we have examined whether Rad3 kinase activity decreases in hsk1-89. We have not detected significant difference in the extent of Mrc1 phosphorylation between the Rad3 from the wild-type and that from the hsk1-89 cells (Fig. 4A, lanes 4–7). Similarly, the Hsk1 kinase activity was not affected by rad3Δ (Fig. 4B, lanes 5–8). These results indicate that Rad3 and Hsk1 kinase activities do not cross-regulate with each other, although we cannot exclude a possibility that they functionally interact in a more local manner such as at the stalled forks.

Figure 4.

Rad3 or Hsk1 kinase activity is not affected in hsk1-89 or rad3Δ cells, respectively. Kinase assays were conducted as described in “Experimental Procedures” with anti-Myc antibody (A) or anti-Flag antibody (B) immunoprecipitates. (A) Extracts were prepared from non-tagged (lanes 2 and 3, YM71), Myc-tagged Rad3 (lanes 4 and 5, SH5142) and Myc-tagged Rad3 hsk1-89 (lanes 6 and 7, SH5431) strains. Cells were grown at 25°C and 12 mM HU was added (lanes 3, 5 and 7) or non-treated (lanes 2, 4 and 6), and incubation was continued for 1.5 hrs at 30°C. Lane 1, reaction without kinase. The reactions were conducted in the presence of 8 mM magnesium acetate, and thus the background phosphorylation of Mrc1 in non-tagged extract is observed. The shifted band, representing Rad3-mediated phosphorylation, is generated only by the tagged extract. Upper, autoradiogram; middle, silver staining; lower, immunoblot with anti-Myc antibody. (B) Extracts were prepared from non-tagged (lanes 1–4) or Flag-tagged Hsk1 (lanes 5–8) strain. Lanes 1, 2, 5 and 6, rad3+: lanes 3, 4, 7 and 8; rad3Δ. Cells were grown at 30°C and 12 mM HU was added (lanes 2, 4, 6 and 8) or non-treated (lanes 1, 3, 5 and 7), followed by further incubation for 1.5 hrs. Lane 9, reaction with purified Hsk1-Dfp1/Him1 complex; lane 10, reaction without kinase. Lanes 1 and 2, YM71; lanes 3 and 4, NI392; lanes 5 and 6, MS337; lanes 7 and 8, MS420. Upper, autoradiogram; lower, silver staining.

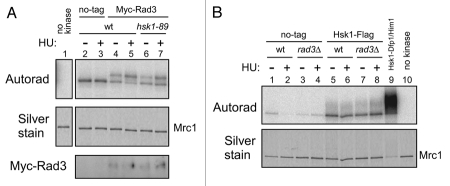

Mrc1 is phosphorylated by both Rad3 and Hsk1 kinases in vitro.

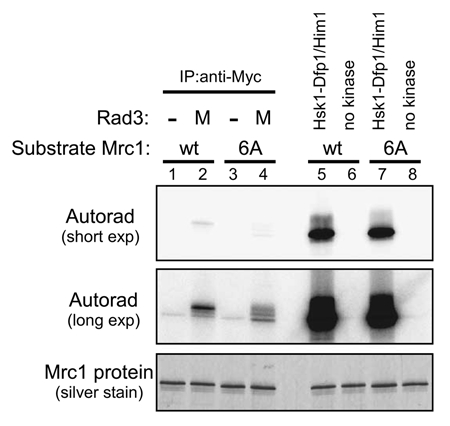

Purified Hsk1-Dfp1/Him1 kinase efficiently phosphorylates purified Mrc1 protein.28 We estimate about 2–3 molecules of phosphates incorporated on an average per a molecule of Mrc1 protein, based on the quantification of the level of 32P incorporation. The Vmax and Km for the substrate Mrc1 protein was estimated to be 0.154 pmole/min and 9.0 nM (Sup. Fig. 3), comparable to or even better than those estimated for the MCM substrate of human Cdc7 kinase.28 We also purified the Mrc1-6A mutant protein in which the six SQ/TQ sites in the SQ/TQ clusters were mutated to AQ23 and compared the level of phosphorylation by Hsk1 kinase. The level of phosphorylation was not significantly affected by the 6A mutation (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 7), indicating that Hsk1 mainly phosphorylates other serine/threonine residues of Mrc1 in vitro. Indeed, Mrc1 did not react with the phosphorylated SQ/TQ antibody after phosphorylation by Hsk1 (Sup. Fig. 4B). We also conducted Rad3 kinase assays with this mutant Mrc1 protein as a substrate. Wild-type Mrc1 was phosphorylated by Rad3, generating a hyper-shifted form, reminiscent to what is observed in vivo (Fig. 5, lane 2). Rad3 did phosphorylate the 6A mutant, albeit at a reduced level, but the characteristic mobility-shift was largely lost (Fig. 5, lane 4). These results indicate that at least some of the six SQ/TQ sites in the SQ/TQ cluster of Mrc1 are phosphorylated by Rad3 (and likely Tel1) both in vivo and in vitro. Thus, Hsk1 somehow stimulates the Rad3-mediated phosphorylation of these SQ/TQ sites on Mrc1. We attempted to “pre-phosphorylate” Mrc1 with Hsk1 and then examine whether this stimulated Rad3-mediated phosphorylation, but we did not observe such an effect (Sup. Fig. 4). We co-overexpressed Hsk1-Dfp1/Him1 (wild-type or kinase.negative) and Mrc1 in E. coli cells and purified Mrc1 in order to generate Mrc1 protein that has been phosphorylated by Hsk1. We then compared the efficacy of Rad3-mediated phosphorylation of the non-treated Mrc1 and Hsk1-treated Mrc1. We did not detect a difference in the extent of phosphorylation (Sup. Fig. 4), suggesting that Rad3 action on Mrc1 is not affected by prior phosphorylation by Hsk1.

Figure 5.

Effect of a mutation of the SQ/TQ cluster of Mrc1 protein on its phosphorylation in vitro. Kinase assays were conducted as described in “Experimental Procedures” with anti-Myc antibody immunoprecipitates (lanes 1–4), with purified Hsk1-Dfp1/Him1 complex (lanes 5 and 7) or without kinase (lanes 6 and 8). Extracts were prepared from non-tagged (lanes 1 and 3, YM71) or Myc-tagged Rad3 (lanes 2 and 4, SH5142) strains grown at 30°C. Substrates used were the wild-type Mrc1 protein (lanes 1, 2, 5 and 6) or Mrc1-6A mutant protein (lanes 3, 4, 7 and 8). The proteins were analyzed on 7.5% SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide: bisacrylamide = 99:1). Upper, autoradiogram (short exposure); middle, autoradiogram (long exposure); lower, silver staining.

Cdc45 is required for replication stress-induced hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 and checkpoint activation.

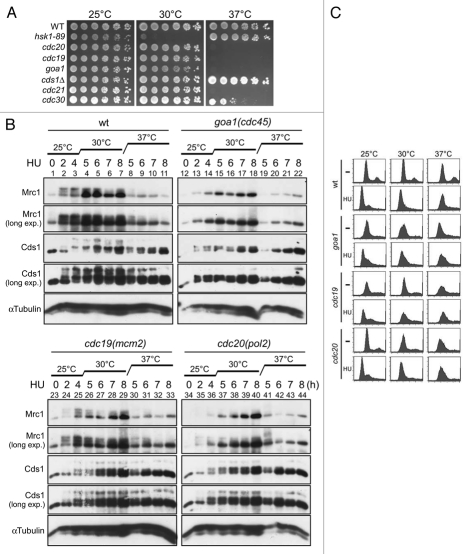

To obtain insights into how Hsk1 is involved in checkpoint-induced hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1, we examined the effects of mutations in other replication factors. The mutants examined were temperature sensitive (ts) mutants of cdc19 (mcm2), goa1 (cdc45) and cdc20 (polε). First, the growth of these strains was examined at various temperatures (Fig. 6A). All the strains except for hsk1-89 exhibited similar growth at 25°C. goa1 (g one arrest 1) arrests the cell cycle with 1C DNA content at a non-permissive temperature, indicative of defect in G1-S transition (Fig. 6C).29 goa1-ts showed poor growth at 30°C, but the cdc19-ts and cdc20-ts strains grew at a rate similar to the wild type at this temperature. At 37°C, these three strains did not show any growth. In contrast, hsk1-89 cells did not grow at 30°C, but grew well at 37°C.

Figure 6.

Effect of HU on the hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 and Cds1 in various replication protein mutants. (A) Cells indicated were serially diluted, spotted on YES plates and were incubated at the temperatures shown for 6 days. (B) YM71 (wild-type), NI291 (cdc19), NI285 (cdc20) or NI735 (goa1) cells were grown at 25°C and 12 mM HU was added and incubation was continued for 4 hrs (lanes 1–3). Then, the temperature was shifted to 30°C or to 37°C for additional 4 hrs (lanes 4–7 or lanes 8–11, respectively). The whole cell extracts prepared at the times (after addition of HU) indicated were analyzed by western blotting using antibodies indicated. The proteins were analyzed on 7.5% SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide:bisacrylamide = 99:1) for Mrc1 and α-tubulin or on 6.5% SDS-PAGE (99:1) containing 25 µM Phos-tag and 50 µM MnCl2 for Cds1 protein. (C) DNA contents of the cells indicated were analyzed by FACS. Cells were grown at 25°C and 12 mM HU was added (HU) or non-treated (-) and incubation of each population was continued at 25°C (the row indicated as “25°C”) or 30°C (the row indicated as “30°C”) or 37°C (the row indicated as “37°C”) for 4 hrs.

We then examined Mrc1 and Cds1 proteins in these strains after treatment with HU. As before, we induced the checkpoint at 25°C, a permissive temperature, by adding HU at 12 mM for 4 hrs, raised the incubation temperature to 30°C or 37°C and then further continued the incubation. The hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 was observed in cdc19-ts cells at 25°C, and this shift was not affected by temperature shift to 30°C. The hyperphosphorylation stayed for 2 hrs after shift to 37°C, similar to the wild type. The phosphorylated form of Cds1 protein was detected for 4 hrs after shift to 37°C. In cdc20-ts cells, the hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 was detected at 30°C, but its level was diminished at 30°C compared to the wild-type. After shift to 37°C, the weak hyperphosphorylation was observed at one hr after shift, but then disappeared. The phosphorylated form of Cds1 protein was detected at 30°C, and also at 37°C albeit at a reduced level. In the goa1-ts mutant, no mobility shift was observed during the entire course of the time course. Even at 25°C, a permissive temperature at which the goa1-ts cells can grow, the hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 was not detected. Similarly, the mobility-shift of Cds1 was not observed at any temperature, except that a weak shifted band appeared at a very late time point (Fig. 6B). Thus, Cdc45 protein seems to be specifically required for HU-induced Cds1 activation, whereas the cdc19-ts mutation has little effect on Cds1 activation even at a non-permissive temperature. The cdc20-ts (polε) mutation appears to affect the HU-responses to a greater extent than cdc19-ts, but the mobility-shift of Mrc1 and Cds1 is still observed, albeit at a reduced level.

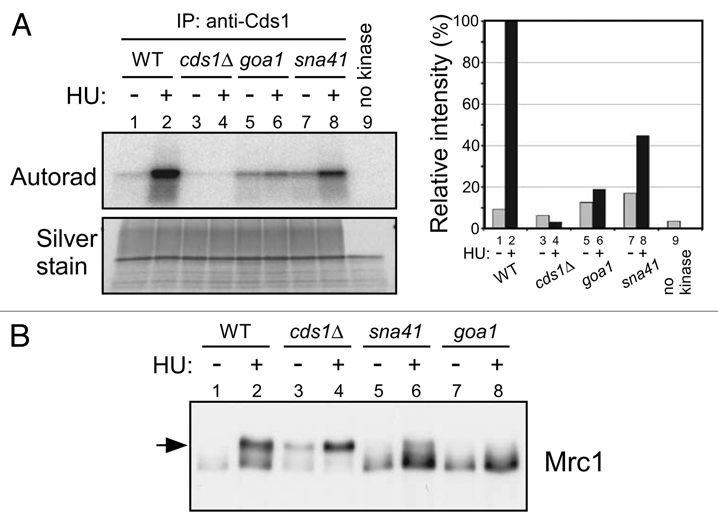

goa1 was originally isolated as G1 arrest mutant, and cannot enter S phase at a non-permissive temperature.29,30 We measured the Cds1 kinase activity in goa1-U53 by directly measuring its kinase activity in the anti-Cds1 antibody immunoprecipitates. At 37°C, Cds1 kinase activity after HU treatment was significantly reduced in goa1-U53. In another allele of cdc45, sna41-928,31 Cds1 kinase activity was also reduced, but more mildly compared to goa1-U53 (Fig. 7A). The hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 was completely gone in goa1-U53, as shown above, and it was also reduced in sna41-928, although a low level of hyperphosphorylated form was observed (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Cds1 kinase activity and Mrc1 hyperphosphorylation in the goa1-U53 and sna41-928 mutants. (A) Kinase assays were conducted with anti-Cds1 antibody immunoprecipitates and MBP (as substrate), as described in “Experimental Procedures”. Wild-type (YM71), cds1Δ (NI453), goa1-U53 (NI735) and sna41-928 (HM328) cells growing exponentially in YES at 30°C were shifted to 37°C for 15 min, followed by incubation with or without 12 mM HU for further 2 h at 37°C. Upper, autoradiogram; lower, silver staining. The level of phosphorylation is shown in the accompanying graph. (B) Cells, as indicated, were grown at 25°C and split into two portions. To one part, 15 mM HU was added and the other half was non-treated and both were further incubated at 30°C for 3 hrs. The whole cell extracts were prepared and were analyzed by western blotting using anti-Myc antibody. Arrow indicates the phosphorylated form of Mrc1 protein that is specifically observed in HU-treated cells. (A) Lanes 1 and 2, YM71; lanes 3 and 4, NI453; lanes 5 and 6, NI735; lanes 7 and 8, HM328. (B) Lanes 1 and 2, YM71; lanes 3 and 4, NI453; lanes 5 and 6, HM328; lanes 7 and 8, NI735.

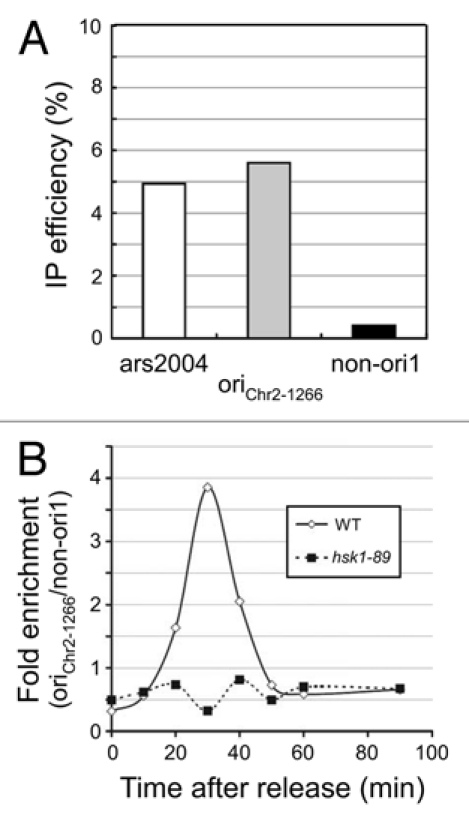

In budding yeast, Cdc7 is known to be required for loading of Cdc45 onto origins.32 Similarly, in Xenopus egg extracts and human cells, Cdc7 has been shown to be required for loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin.16,33,34 We also previously reported that Hsk1 is required for chromatin loading of Cdc45.16 In order to show more directly that Hsk1 is required for loading of Cdc45 onto origins, we conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation assays of Cdc45. oriChr2-1266 is an early-firing origin, which fires in the presence of HU (Fig. 8A),35,36 and Cdc45 binds to this origin at an early S phase in cell cycle-synchronized cells (Fig. 8B). On the other hand, in hsk1-89 cells, binding of Cdc45 to this origin was not observed under the same condition (Fig. 8B). It was previously reported that Cdc45 loading onto ARS2004 requires Hsk1 function.37 Thus, these results are consistent with the critical role of the initiation function of Cdc45, namely the loading onto replication origins, in Cds1 activation.

Figure 8.

Hsk1 is required for association of Cdc45 with an early-firing origin. (A) nda3-KM311 cells arrested in M phase were released into YES media containing 25 mM HU and 200 µM BrdU at 30°C. After incubation for 30 min, cells were harvested and BrdU incorporation at ars2004 (a known early-firing origin), oriChr2-1266 and non-ori1 genomic loci were analyzed as described in “Experimental Procedures”. (B) The wild-type or hsk1-89 cells were released from M phase at 30°C, as described in “Experimental Procedures”. Cdc45-3Flag was immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody at each time point indicated. Co-immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified by real-time PCR. Signal enrichment was calculated by normalizing the amount of precipitated oriChr2-1266 DNA by that of precipitated non-ori1 DNA. The suffix in oriChr2-1266 indicates the distances in kilobase pairs from the left end of the Chromosome 2. oriChr2-1266 corresponds to Ori2059 in reference 35.

Discussion

A series of signal transduction pathways are induced when replication fork is blocked. In this so-called replication stress checkpoint pathway, the initial cellular reaction is activation of the sensor kinase, Rad3 in fission yeast or ATR in mammalian cells, which is followed by activation of a transducer/adapter protein, Mrc1 in fission yeast or Claspin in mammals, ultimately leading to activation of “effector” checkpoint kinases, Cds1 in fission yeast or Chk1 in mammals.1,38 The effector kinases then regulate the progression of S phase or M phase. We have shown that Cdc7 kinase is required for the activation of the checkpoint kinase in response to replication fork stress both in fission yeast and mammals.19,20 More recently, it was shown, by using a Cdc7 bypass strain, that Cdc7 is required for replication stress-induced activation of Rad53 checkpoint kinase in budding yeast.18 In this communication, we have shown that Hsk1 kinase activity is required for induction and maintenance of hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 induced by replication fork block.

Activation of Cds1 effector kinase in response to HU addition is severely compromised in hsk1-89 mutant at the non-permissive temperature.20 Activation of Cds1 kinase was assessed in other temperature-sensitive mutants (such as cdc19 and cdc20) defective in the processes of DNA replication. In these mutants, FACS profile of DNA contents suggested arrest in late S to G2 phase (data not shown). However, Cds1 kinase appeared to be still activated by HU in theses mutants at a nonpermissive temperature (Fig. 6B), suggesting that Hsk1 is specifically required for Cds1 kinase activation.

Mrc1 is hyperphosphorylated upon HU treatment, and this phosphorylation is required for Cds1 activation.9,21,23 We found that it is dependent not only on Rad3/Tel1, but also on Hsk1 function (Fig. 1A and B). Inactivation of Hsk1 after Mrc1 is hyperphosphorylated by HU leads to rapid loss of its hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 1C), indicating that Hsk1 is required for maintaining the phosphorylated state of Mrc1.

The HU-induced hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 is completely lost in rad3Δ tel1Δ and also in mrc1-6A mutant, in which the Rad3 target sites are mutated.23 The mobility-shift of Mrc1 by Rad3 kinase in vitro also depends on these sites (Fig. 5). Thus, one possibility is that Rad3 is inactive in hsk1-89 cells. However, we did not observe any difference in Rad3 kinase activity between the wild type and hsk1-89 cells (Fig. 4A). The active Rad3 kinase in hsk1-89 cells suggests that at least part of the initial “sensor” step for the stalled replication fork may be intact in this mutant. Hsk1 kinase activity was not affected by rad3Δ (Fig. 4B), indicating that Rad3 and Hsk1 kinases function independently. We previously showed that replication stress-induced relocation of ATR in nucleus is not affected by Cdc7 depletion in mammalian cells.19

How does Hsk1 contribute to hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 after replication stress? Rad3 may recognize Mrc1 in complex with Hsk1 more efficiently than free Mrc1, since we previously reported that Hsk1 interacts with Mrc1.39 However, kinase activity of Hsk1 is required for Mrc1 hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 2), suggesting that Hsk1-Mrc1 interaction alone is not sufficient. Thus, prior phosphorylation of Mrc1 by Hsk1 may stimulate the Rad3-mediated phosphorylation of the SQ/TQ cluster of Mrc1 protein. However, prior phosphorylation of Mrc1 with Hsk1 (either by purified kinase or coexpression in E. coli cells) did not result in enhanced phosphorylation of SQ/TQ sites of Mrc1 by Rad3 kinase (Sup. Fig. 4).

We therefore examined the effect of mutations of other replication factors on HU-induced checkpoint activation. cdc19 encodes MCM2, essential for preRC formation. cdc19-P1 mutation is known to cause loss of viability at a non-permissive temperature with reduced amount of mcm40 and suggested to have a defect in elongation phase of DNA replication.41 cdc20 encodes a catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase ε and is essential for initiation.42 goa1+ encodes Cdc45 and goa1-U53 mutant arrests with 1C DNA content with defect in initiation.29,30 We found that Cds1 is activated and Mrc1 is hyperphosphorylated in cdc19-P1 at a permissive temperature and temperature shift to a non-permissive temperature did not eliminate hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 or Cds1 in this mutant. Similarly, Cds1 and Mrc1 hyperphosphorylation was observed in cdc20 at both permissive and non-permissive temperatures, although their extents were reduced compared to wild-type or cdc19-P1. Similarly, hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 in response to HU was observed in cdc30 encoding Orp1 or in cdc21 encoding Mcm4 (data not shown). In contrast, Cds1 activation and hyperphosphorylation of Mrc1 was almost completely inhibited in goa1 mutant even at a permissive temperature (Fig. 6B). This indicates that sufficient level of Cdc45 activity is required for checkpoint activation in fission yeast cells.

It has been known that Cdc7 is required for loading of Cdc45 onto preRCs at origins in budding yeast.32 We show that Hsk1 is required for loading of Cdc45 onto an early-firing origin in fission yeast (Fig. 8). Our results indicate specific and essential roles of Hsk1-Cdc45 in activation of replication checkpoint. It has been reported in budding yeast that sufficient levels of preRC are required for checkpoint activation.11 The results reported here suggest that activated origins, more specifically the loading of Cdc45 at the origins, rather than the presence of preRC, may be critical for checkpoint activation. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that in budding yeast most of the preRC are utilized, while in fission yeast, only subset of the preRC is actually utilized for initiation,35,36 thus making the effect of the preRC defect less profound.

Studies in Xenopus egg extracts indicated that specific structures including primed single-stranded DNA are sufficient for activation of checkpoint.43,44 Since the generation of these structures would require the loading of Cdc45 and formation of an active replication fork, requirement of Hsk1 and Cdc45 may simply reflect the necessity to generate sufficient numbers of replication fork structures. However, cdc20 (polε) mutant which is a part of the fork assembly can activate checkpoint, indicating that assembly of fully-equipped replisome may not be necessary for checkpoint activation. Partial defect in Cds1 activation as well as in Mrc1 hyperphosphorylation was observed also in another allele of cdc45, sna41-928 (Fig. 7). It was reported before that loading of Cdc45 onto origins is reduced in sna41-928.31 More severe effect on Mrc1 and Cds1 activation was observed in goa1-U53 than in sna41-928. This is probably because of intrinsic difference between these mutant alleles. goa1-U53 is specifically defective in initiation and arrest with 1C DNA content at the non-permissive temperature, whereas sna41-928 is defective in both initiation and elongation and arrests with mostly S phase DNA content at the nonpermissive temperature.31,45 These observations further reinforce our conclusion that the initiation step, i.e., the loading of Cdc45 onto origins, is crucial for checkpoint activation. Our results also suggest that continuous loading of Cdc45 onto origins may be required to maintain the activated state of Cds1.

We cannot exclude the possibility that an unknown Hsk1 substrate may be required for HU-induced checkpoint reactions. Another possibility is that Hsk1, together with Cdc45, may be actively required to maintain the proper replication fork structure capable of sending the checkpoint signals, and disruption of this structure in hsk1-89 may lead to inefficient phosphorylation by Rad3/Tel1 kinase. Rapid loss of the hyperphosphorylated form of Mrc1 after shift of hsk1-89 to a non-permissive temperature is consistent with this possibility. More experiments are needed to evaluate these possibilities.

Experimental Procedures

Fission yeast strains.

General techniques. Methods for genetic and biochemical analyses of fission yeast have been described previously in reference 46 and 47. Fission yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

| YM71 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 |

| KO147 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 hsk1-89:ura4+ |

| NI392 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 rad3::ura4+ |

| MS335 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 hsk1-3FLAG:kan |

| MS337 | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 hsk1-3FLAG:kan |

| MS113 | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 cds1::ura4+ hsk1-3FLAG:kan |

| MS420 | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 hsk1-3FLAG:kan rad3::ura4+ |

| KT2791 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 mrc1-13myc:kan |

| SH2219 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 swi1-3FLAG:kan mrc1-13myc:kan |

| MS346 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 mrc1-13myc:kan hsk1-89:ura4+ |

| MS401 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 mrc1-13myc:kan swi1::kan |

| NI453 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 cds1::ura4+ |

| MS252 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 mrc1::kan |

| NI485 | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6 rad3::ura4+ |

| SH5142 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-704 rad3-nmycx8 |

| SH5431 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6 rad3-nmycx8 hsk1-89:ura4+ |

| NI285 | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6 cdc20 |

| NI291 | h+ leu1-32 cdc19-P1 |

| NI735 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 goa1-U53 |

| MS193 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 cdc21 |

| NI920 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 cdc30 |

| HM328 | h- sna41-928 |

| HM360 | h+ leu1-32 mrc1-13myc:kan cdc45-3FLAG:kan nda3-KM311 |

| HM363 | h+ leu1-32 mrc1-13myc:kan cdc45-3FLAG:kan hsk1-89:ura4+ nda3-KM311 |

| KYP103 | h- leu1-32 ura4-D18 cdc21-3FLAG:kan aur:aur1r-Adh1-TKAdh1-scENT1 nda3-KM311 |

Preparation of extracts from yeast cells.

For immunoblotting, whole cell extracts from approximately 107 cells were made by the “boiling method”, as described previously.48 For immunoprecipitation, approximately 108 cells from 50 ml culture were harvested and washed once with PBS. The cells were then resuspended in 0.5 ml of IP buffer (20 mM Hepes KOH [pH 7.6], 50 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 0.1 M sorbitol, 0.1% TritonX-100, 2 mM DTT, 20 mM NaOVa, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate and Sigma protease inhibitors) and were broken with glass beads using a Multi-Beads Shocker (Yasui Kikai; Osaka, Japan). The resulting high speed supernatants were used for immunoprecipitation, as described previously in reference 39.

Detection of phosphorylation-induced mobility-shift of proteins on SDS-PAGE.

Phosphorylation of Mrc1 and Cds1 was detected on 7.5% SDS-PAGE (99:1) or 8% SDS-PAGE (59:1), respectively, which was run at 200V. In some cases, mobility shift was analyzed by running the samples on SDS-PAGE containing 25 µM phos-tag (NARD institute, Hyogo, Japan) prepared according to the manufacturer's recommendations. In Mn2+-Phos-tag-modified acrylamide gel, phosphorylated proteins migrate slower than non-phosphorylated proteins due to the interaction of phosphate groups with Mn2+-Phos-tag.

Antibodies.

Mouse anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma), mouse anti-Myc (A-14) monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz), and mouse anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (B-5-1-2, Sigma) were used. Rabbit anti-Hsk1 antibody, rabbit anti-Dfp1/Him1 antibody and Rabbit anti-Mrc1 antibody were described previously in reference 39 and 48. Rabbit anti-Cds1 antibody was a kind gift from Dr. Teresa Wang and Dr. Nick Rhind.

In vitro kinase assays of Hsk1 kinase.

The total cell extracts were prepared from the cells expressing Flag-tagged Hsk1 at the hsk1+ genomic locus. Hsk1 kinase was immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were used for in vitro kinase assays using Mrc1 protein as a substrate. The immunoprecipitates similarly prepared from the extract of a non-tagged strain were used as a negative control. Mrc1 protein with N-terminal RGS-his tag and C-terminal Flag tag was overproduced in insect cells or in E. coli and was purified as described in reference 49. Hsk1 in a complex with GST-tagged Dfp1/Him1 was overproduced in insect cells, purified with glutathione Sepharose beads and was used for a positive control reaction.

In vitro kinase assays of Cds1 kinase.

Cds1 kinase assays were conducted by using immunoprecipitated Cds1 on MBP as a substrate.20 Kinase assays of Cds1 were conducted also by incubating the cell lysates with [γ-32P] ATP in the presence of GST-Wee170 polypeptide27 and analyzing the phosphorylation of GST-Wee170 after pull-down with glutathione Sepharose beads.

In vitro kinase assays of Rad3 kinase.

The total cell extracts were prepared from the cells expressing Myc-tagged Rad3 at the rad3+ genomic locus. Rad3 kinase was immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc antibody. The immunoprecipitates similarly prepared from the extract of a non-tagged strain were used as a negative control. The immunoprecipitates were used for in vitro kinase assays using Mrc1 protein mentioned above as a substrate in a reaction mixture containing 40 mM Hepes KOH [pH 7.6], 40 mM potassium glutamate, 1 mM DTT, 8 mM MnCl2 and 100 µM ATP with [γ-32P] ATP. In some experiments, 8 mM magnesium acetate was used in place of MnCl2.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay and realtime PCR.

nda3-KM311 strains were incubated at 20°C for 5 h (or 8 h for the cells with hsk1-89 background) to induce arrest in M phase and then released into growth by shifting to 30°C, a restriction temperature for hsk1-89. ChIP assay was performed as described previously in reference 37 and 50 with some modifications. We disrupted collected cells (2.5 × 108 cells) by Multi-beads Shocker (Yasui-kikai Co., Osaka) and DNA was sheared to about 600 bp by sonication. Immunoprecipitation was performed by using monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody (SIGMA). After incubation of lysate with antibody and protein G beads (Dynal) for 3 h, beads were washed three times with buffer. Co-immunoprecipitated DNA was purified by MiniElute Reaction Cleanup Kit (QIAGEN). The following primers were used for amplifying the DNA: oriChr2-1266, sense 5′-GAG GAA AGG GGT GAA AGA A-3′, anti-sense 5′-CGC TAC AAC AAT CCC TAA A-3′; ars2004, sense 5′-CTT TTG GGT AGT TTT CGG ATC C-3′, anti-sense 5′-ATG AGT ACT TGT CAC GAA TTC-3′; non-ori1, sense 5′-TCG AAG ATC CTA CCG CTT TC-3′, anti-sense 5′-GAT TCA CAT AAC CCG CTA GC-3′. Real-time PCR was performed by using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TAKARA) and LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics). The extent of enrichment of origin DNA was calculated as follows. The levels of amplified oriChr2-1266, ars2004 and non-ori1 (30 kb away from ars2004) DNA fragments were determined by real-time PCR, and then the ratio of oriChr2-1266 to non-ori1 or ars2004 to non-ori1 was calculated for each time point. BrdU incorporation and ChIP analyses were performed as described in reference 50.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Kanji Furuya and Antony M. Carr for the gift of Myc-tagged rad3 strains. We thank Drs. Teresa Wang and Nick Rhind for anti-Cds1 antibody. We thank Drs. Hisao Masukata and Takuro Nakagawa for plasmids, strains and antibody. We would like to thank the members of our laboratory for useful discussion. This work was supported in part by Grantin-Aid for Scientific Research (A) and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Area “Chromosome Cycle” from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, by Takeda Science Foundation, by Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders (to H.M.), by research fellowships of the Japan Society for Promotion of Science for young scientist (to M.H.) and by NIH grant GM59447 (to P.R.).

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/13937

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Boddy MN, Russell P. DNA replication checkpoint. Curr Biol. 2001;11:953–956. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 2004;432:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature03097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert S, Carr AM. Checkpoint responses to replication fork barriers. Biochimie. 2005;87:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGlynn P, Lloyd RG. Recombinational repair and restart of damaged replication forks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:859–870. doi: 10.1038/nrm951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyberg KA, Michelson RJ, Putnam CW, Weinert TA. Toward maintaining the genome: DNA damage and replication checkpoints. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:617–656. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.060402.113540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segurado M, Tercero JA. The S-phase checkpoint: targeting the replication fork. Biol Cell. 2009;101:617–627. doi: 10.1042/BC20090053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branzei D, Foiani M. Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:208–219. doi: 10.1038/nrm2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu YJ, Davenport M, Kelly TJ. Two-stage mechanism for activation of the DNA replication checkpoint kinase Cds1 in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 2006;20:990–1003. doi: 10.1101/gad.1406706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu YJ, Kelly TJ. Autoinhibition and autoactivation of the DNA replication checkpoint kinase Cds1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16016–16027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900785200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimada K, Pasero P, Gasser SM. ORC and the intra-S-phase checkpoint: A threshold regulates Rad53p activation in S phase. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3236–3252. doi: 10.1101/gad.239802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van C, Yan S, Michael WM, Waga S, Cimprich KA. Continued primer synthesis at stalled replication forks contributes to checkpoint activation. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:233–246. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston LH, Masai H, Sugino A. A Cdc7p-Dbf4p protein kinase activity is conserved from yeast to humans. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2000;4:61–69. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4253-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly TJ, Brown GW. Regulation of chromosome replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:829–880. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masai H, Arai KI. Cdc7 kinase complex: a key regulator in the initiation of DNA replication. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:287–296. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masai H, Taniyama C, Ogino K, Matsui E, Kakusho N, Matsumoto S, et al. Phosphorylation of MCM4 by Cdc7 kinase facilitates its interaction with Cdc45 on the chromatin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39249–39261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheu YJ, Stillman B. Cdc7-Dbf4 phosphorylates MCM proteins via a docking site-mediated mechanism to promote S phase progression. Mol Cell. 2006;24:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheu YJ, Stillman B. The Dbf4-Cdc7 kinase promotes S phase by alleviating an inhibitory activity in Mcm4. Nature. 2010;463:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature08647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JM, Kakusho N, Yamada M, Kanoh Y, Takemoto N, Masai H. Cdc7 kinase mediates Claspin phosphorylation in DNA replication checkpoint. Oncogene. 2008;27:3475–3482. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeda T, Ogino K, Tatebayashi K, Ikeda H, Arai K, Masai H. Regulation of initiation of S phase, replication checkpoint signaling, and maintenance of mitotic chromosome structures during S phase by Hsk1 kinase in the fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1257–1274. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.5.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alcasabas AA, Osborn AJ, Bachant J, Hu F, Werler PJ, Bousset K, et al. Mrc1 transduces signals of DNA replication stress to activate Rad53. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:958–965. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka K, Russell P. Mrc1 channels the DNA replication arrest signal to checkpoint kinase Cds1. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:966–972. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H, Tanaka K, Nogochi E, Nogochi C, Russell P. Replication checkpoint protein Mrc1 is regulated by Rad3 and Tel1 in fission yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8395–8403. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8395-8403.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tercero JA, Longhese MP, Diffley JFX. A central role for DNA replication forks in checkpoint activation and response. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1323–1336. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogino K, Takeda T, Matsui E, Iiyama H, Taniyama C, Arai K, et al. Bipartite binding of a kinase activator activates Cdc7-related kinase essential for S phase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31376–31387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basi G, Schmid E, Maundrell K. TATA box mutations in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe nmt1 promoter affect transcription efficiency but not the transcription start point or thiamine repressibility. Gene. 1993;123:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90552-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boddy MN, Furnari B, Mondesert O, Russell P. Replication checkpoint enforced by kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Science. 1998;280:909–912. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kakusho N, Taniyama C, Masai H. Identification of stimulators and inhibitors of Cdc7 kinase in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19211–19218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchiyama M, Arai K, Masai H. Sna41goa1, a novel mutation causing G1/S arrest in fission yeast, is defective in a CDC45 homolog and interacts genetically with polalpha. Mol Genet Genomics. 2001;265:1039–1049. doi: 10.1007/s004380100499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchiyama M, Griffiths D, Arai K, Masai H. Essential role of Sna41/Cdc45 in loading of DNA polymerase alpha onto minichromosome maintenance proteins in fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26189–26196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamada Y, Nakagawa T, Masukata H. A novel intermediate in initiation complex assembly for fission yeast DNA replication. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3740–3750. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou L, Stillman B. Assembly of a complex containing Cdc45p, replication protein A and Mcm2p at replication origins controlled by S-phase cyclin-dependent kinases and Cdc7p-Dbf4p kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:3086–3096. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3086-3096.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walter JC. Evidence for sequential action of cdc7 and cdk2 protein kinases during initiation of DNA replication in Xenopus egg extracts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39773–39778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jares P, Blow JJ. Xenopus cdc7 function is dependent on licensing but not on XORC, XCdc6 or CDK activity and is required for XCdc45 loading. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1528–1540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi M, Katou Y, Itoh T, Tazumi A, Yamada Y, Takahashi T, et al. Genome-wide localization of pre-RC sites and identification of replication origins in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2007;26:1327–1339. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heichinger C, Penkett CJ, Bahler J, Nurse P. Genome-wide characterization of fission yeast DNA replication origins. EMBO J. 2006;25:5171–5179. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yabuuchi H, Yamada Y, Uchida T, Sunathvanichkul T, Nakagawa T, Masukata H. Ordered assembly of Sld3, GINS and Cdc45 is distinctly regulated by DDK and CDK for activation of replication origins. EMBO J. 2006;25:4663–4674. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chini CC, Chen J. Claspin, a regulator of Chk1 in DNA replication stress pathway. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1033–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimmoto M, Matsumoto S, Odagiri Y, Noguchi E, Russell P, Masai H. Interactions between Swi1-Swi3, Mrc1 and S phase kinase, Hsk1 may regulate cellular responses to stalled replication forks in fission yeast. Genes Cells. 2009;14:669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherman DA, Pasion SG, Forsburg SL. Multiple domains of fission yeast Cdc19p (MCM2) are required for its association with the core MCM complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1833–1845. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.7.1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forsburg SL, Nurse P. The fission yeast cdc19+ gene encodes a member of the MCM family of replication proteins. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:2779–2788. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.10.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D'Urso G, Nurse P. Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc20+ encodes DNA polymerase epsilon and is required for chromosomal replication but not for the S phase checkpoint. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12491–12496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacDougall CA, Byun TS, Van C, Yee M, Cimprich KA. The structural determinants of checkpoint activation. Genes Dev. 2007;21:898–903. doi: 10.1101/gad.1522607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shiotani B, Zou L. Single-stranded DNA orchestrates an ATM-to-ATR switch at DNA breaks. Mol Cell. 2009;33:547–558. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nitani N, Nakamura K, Nakagawa C, Masukata H, Nakagawa T. Regulation of DNA replication machinery by Mrc1 in fission yeast. Genetics. 2006;174:155–165. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.060053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alfa C, Fantes P, Hyams J, McLeod M, Warbrick E. Experiments with fission yeast: a laboratory course manual. Plainview: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moreno S, Klar A, Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeda T, Ogino K, Matsui E, Cho MK, Kumagai H, Miyake T, et al. A fission yeast gene, him1(+)/dfp1(+), encoding a regulatory subunit for Hsk1 kinase, plays essential roles in S-phase initiation as well as in S-phase checkpoint control and recovery from DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5535–5547. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka T, Yokoyama M, Matsumoto S, Fukatsu R, You Z, Masai H. Fission yeast Swi1-Swi3 complex facilitates DNA binding of Mrc1. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.173344. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katou Y, Kanoh Y, Bando M, Noguchi H, Tanaka H, Ashikari T, et al. S-phase checkpoint proteins Tof1 and Mrc1 form a stable replication-pausing complex. Nature. 2003;424:1078–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature01900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.