Abstract

Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction that is characterised by a thick greyish-white fibrotic membrane encasing the small bowel. It is difficult to make a definite preoperative diagnosis. We report a successfully treated case of a 42-year-man, presented with sub acute small bowel obstruction caused by SEP. CT showed characteristic findings of small bowel loops congregated to the center of the abdomen encased by a soft-tissue density mantle. He had undergone adhesiolysis and uneventful postoperative period. A high index of clinical suspicion may be generated by the recurrent character of small bowel obstruction combined with relevant imaging findings and lack of other plausible aetiologies. Clinicians must rigorously pursue a preoperative diagnosis, as it may prevent a surprise upon laparotomy and result in proper management.

Background

The sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction, which is characterised by the encasement of the small bowel by a fibrocollagenic cocoon like sac. It was first observed by Owtschinnikow in 1907 and was called peritonitis chronica fibrosa incapsulata.1 SEP can be classified as idiopathic or secondary. The idiopathic form is also known as abdominal cocoon,1 the aetiology of this entity has remained relatively unknown.

Case presentation

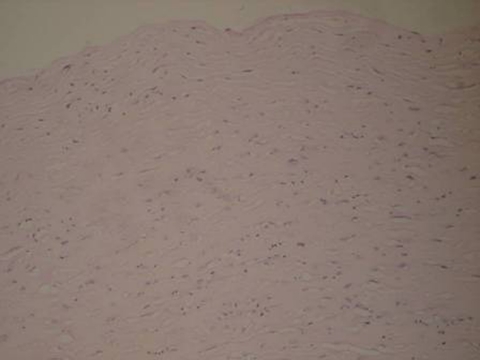

A 42-year-old man presented in surgical outpatient department with 4 days history of colicky abdominal pain, bilious vomiting and constipation. He reported two similar episodes, attributed to small bowel obstruction in the past 4 months, which required hospitalisation and resolved with conservative treatment at district hospital. He had no surgical or other medical history. On examination, he was in distress, but afebrile and haemodynamically stable. His abdomen was distended but non-tender, with increased bowel sounds in pitch and frequency. No palpable abdominal mass or organomegaly and no external hernias were present. He had undergone laparotomy on day 2. The histological examination of the membranous tissue shows proliferation of fibroconnective tissue with non-specific chronic inflammatory reaction (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The histological examination of the membranous tissue (haematoxylin and eosin stain, original magnification, ×40) shows proliferation of fibroconnective tissue with non-specific chronic inflammatory reaction.

Investigations

Blood and urine investigations were normal.

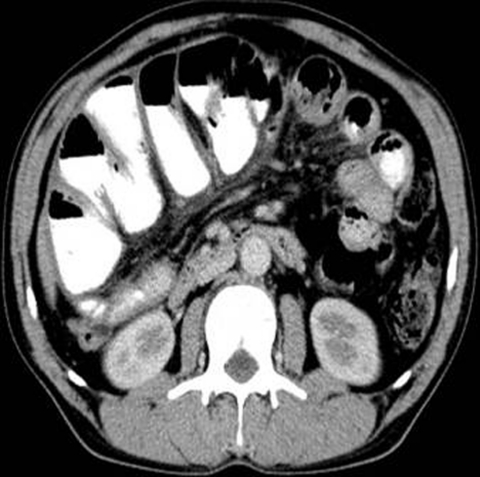

Plain abdominal x-ray showed few air-fluid levels centrally located, without free intraperitoneal gas. Ultrasound of the abdomen did not reveal any abnormalities. Contrast-enhanced abdomen CT, performed on the same day, showing small bowel loops congregated to the center of the abdomen encased by a soft-tissue density mantle, diagnosing small bowel obstruction caused by idiopathic SEP (abdominal cocoon) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

MDCT of the abdomen, axial section showing characteristic findings of small bowel loops congregated to the center of the abdomen encased by a soft-tissue density mantle.

Treatment

On surgery, a fibrous capsule covering all the abdominal viscera was revealed, in which small bowel loops were encased, with the presence of interloop adhesions. The liver, stomach, appendix, right and left colon, as well as the sigmoid, were also covered and the greater omentum looked hypoplastic and encased in fibrous tissue (figure 3). Incision of the thick membrane and extensive adhesiolysis of small bowel loops were performed without loop resection.

Figure 3.

Operative photograph demonstrating thick membrane encasing the small bowel.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged home on the fifth postoperative day. He has been fit and healthy and completely symptom free for last 4 months.

Discussion

SEP is a rare condition of unknown aetiology in clinical cases. It is characterised by a thick greyish-white fibrotic membrane, partially or totally encasing the small bowel.1 The fibrocollagenic cocoon can extend to involve other organs like the large intestine, liver and stomach.2 Clinically, it presents with recurrent episodes of acute, subacute or chronic small bowel obstruction, weight loss, nausea and anorexia and at times with a palpable abdominal mass, but some patients may be asymptomatic.2

SEP can be classified as idiopathic or secondary. The secondary form of SEP has been reported in association with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Other rare causes include abdominal tuberculosis, β-blocker practolol intake, ventriculoperitoneal and peritoneovenous shunts, orthotopic liver transplantation3 and recurrent peritonitis,4 all of which were absent in our patients. The idiopathic form also known as abdominal cocoon has been classically described in young adolescent females from the tropical and subtropical countries. The aetiology of this entity has remained relatively unknown. To explain the aetiology, a number of hypotheses have been proposed. These include retrograde menstruation with a superimposed viral infection,1 retrograde peritonitis and cell-mediated immunological tissue damage incited by gynaecological infection.5 However, since this condition has also been seen to affect males, premenopausal females and children, there seems to be little support for these theories.2 Further hypotheses are therefore needed to explain the cause of idiopathic SEP. Since abdominal cocoon is often accompanied by other embryologic abnormalities such as greater omentum hypoplasia, and developmental abnormality may be a probable aetiology.3 In our study, greater omentum hypoplasia was demonstrated. To elucidate the precise aetiology of idiopathic SEP, further studies of cases are necessary.

Although it is difficult to make a definite preoperative diagnosis, most cases are diagnosed incidentally at laparotomy, and a better awareness of this entity and the imaging techniques may facilitate preoperative diagnosis.6 Ultrasonography may show a thick-walled mass containing bowel loops, loculated ascites and fibrous adhesions.4 Barium small bowel series showed the ileal loops clumped together within a sac, giving a cauliflower-like appearance on sequential films. In our study, we successfully diagnosed abdominal cocoon, by a combination of abdominal CT and clinical presentations. The characteristic findings of CT include that small bowel loops congregated to the center of the abdomen, encased by a soft-tissue density mantle which cannot be contrast enhanced, and interloops collection was demonstrated.

Management of SEP is debated. But most authors agreed that surgical treatment is required. At surgery, in addition to careful dissection and excision of the covering membrane, dense interbowel adhesions also need to be freed for complete recovery.7 In order to avoid complications of postoperative intestinal leakage and short-intestine syndrome, resection of the bowel is indicated only if it is non-viable. No surgical treatment is required in asymptomatic SEP. Surgical complications were reported including intra-abdominal infections, enterocutaneous fistula and perforated bowel.8 In the present patients, no recurrence and complication were described in postoperative follow-up.

Learning points.

-

▶

Idiopathic SEP, a rare cause of a common surgical emergency such as small bowel obstruction, may be responsible, especially in cases with recurrent attacks of non-strangulating obstruction in the same individual.

-

▶

A high index of clinical suspicion may be generated by the recurrent presentation of small bowel ileus combined with relevant imaging findings and lack of other aetiologies.

-

▶

Clinicians must rigorously pursue a preoperative diagnosis, as it may prevent a ‘surprise’ upon laparotomy and unnecessary procedures for the patient, such as bowel resection.

-

▶

Careful dissection and excision of the thick sac with the release of the small intestine leads to complete recovery.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Foo KT, Ng KC, Rauff A, et al. Unusual small intestinal obstruction in adolescent girls: the abdominal cocoon. Br J Surg 1978;65:427–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoon YW, Chung JP, Park HJ, et al. A case of abdominal cocoon. J Korean Med Sci 1995;10:220–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devay AO, Gomceli I, Korukluoglu B, et al. An unusual and difficult diagnosis of intestinal obstruction: The abdominal cocoon. Case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg 2006;1:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu P, Chen LH, Li YM. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (or abdominal cocoon): a report of 5 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:3649–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narayanan R, Bhargava BN, Kabra SG, et al. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. Lancet 1989;2:127–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamoto H. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis–a clinician’s approach to diagnosis and medical treatment. Perit Dial Int 2005;25 Suppl 4:S30–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serafimidis C, Katsarolis I, Vernadakis S, et al. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (or abdominal cocoon). BMC Surg 2006;6:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masuda C, Fujii Y, Kamiya T, et al. Idiopathic sclerosing peritonitis in a man. Intern Med 1993;32:552–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]