Abstract

Background

Recent efforts to improve neurological care in resource-limited settings have focused on providing training to non-physician healthcare workers.

Methods

A one-day neuro-HIV training module emphasizing HIV-associated dementia (HAD) and peripheral neuropathy was provided to 71 health care workers in western Kenya. Pre- and post-tests were administered to 55 participants.

Results

Mean age of participants was 29 years, 53% were clinical officers and 40% were nurses. Self-reported comfort was significantly higher for treating medical versus neurologic conditions (p<0.001). After training, participants identified more neuropathy etiologies (pre=5.6/9 possible correct etiologies; post=8.0/9; p<0.001). Only 4% of participants at baseline and 6% (p=0.31) post-training could correctly identify HAD diagnostic criteria, though there were fewer mis-identified criteria such as abnormal level of consciousness (pre=82%; post=43%; p<0.001) and hallucinations (pre=57%; post=15%; p<0.001).

Conclusions

Healthcare workers were more comfortable treating medical than neurological conditions. This training significantly improved knowledge about etiologies of neuropathy and decreased some misconceptions about HAD.

Keywords: neuro-infectious disease, training, healthcare workers, HIV, Africa, neuro-HIV

INTRODUCTION

Neurologic disease is common in the developing world where brain disorders affect more than 250 million people.1 In sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest global burden of HIV infection, neurologic complications of HIV infection are also widespread.2 In fact, many of these conditions are more common in sub-Saharan Africa where patients often present for care at more advanced disease stages, and neurotoxic medications such as isoniazid and stavudine are more commonly used than in the developed world.2-4

The most common neurological complication of HIV is peripheral neuropathy, with prevalence estimates in sub-Saharan African cohorts exposed to antiretrovirals ranging from 49-73%.5-7 HIV-associated dementia (HAD) is also common, affecting 7%-28% of HIV-infected persons in the developed world.8-10 Studies from sub-Saharan Africa with varied methodology have found similar results with prevalences ranging from 2-54%.11-14 While little data is available from Kenya, where this study took place, small studies have demonstrated that 36-53% of HIV-infected Kenyans have peripheral neuropathy while 20% have HAD and up to 50% demonstrate sub-clinical neurocognitive impairment.15-18

However, neurologic resources in developing countries are scarce. For example, there are only 0.03 neurologists per 100,000 population in Africa as compared to more than 5 neurologists per 100,000 population in the United States.1, 19 Even these numbers do not accurately reflect access to neurologists in rural regions, as most neurologists in the developing world are in private practice in large cities.20 In Kenya, there are only 11 neurologists for a population of nearly 40 million people, and in Nyanza province, where this study took place, there is one neurologist who sees patients one day per month at a private clinic.20, 21

Diagnostic capacity for neurologic disorders are also lacking in the developing world, including Kenya. While computed tomography (CT) is available at all provincial hospitals and many private hospitals in Kenya, it is largely unaffordable. The average CT cost is approximately $100, while the average Kenyan income is approximately $400.22 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more expensive than CT and only available in the capital city, Nairobi.23 Even lumbar punctures are usually performed only at larger district and tertiary referral hospitals, and the cerebrospinal fluid diagnostic studies are usually limited to microscopy and assessment of glucose and protein.

Training new neurologists to meet the demands for neurologic care in sub-Saharan Africa is not feasible in the short-term.1, 24, 25 In 2006, only four countries in Africa had neurology training programs, of which one was in sub-Saharan Africa.19, 26 One potential solution to the shortage of neurologists is task-shifting, or the process of delegating health care tasks to less specialized health workers. However, most non-physician healthcare workers in primary care setting have received little training in neurology although they already deliver most neurologic care in sub-Saharan Africa.24, 27 For example, a survey of primary healthcare workers in Zambia revealed that two-thirds felt inadequately trained to care for seizures and even more reported inadequate expertise for other neurologic conditions.27 Recent regional initiatives have endorsed providing additional neurologic education to non-physician healthcare workers in order to improve neurologic care in resource-constrained settings.1, 24-28 Our objective was to assess training needs among non-physician healthcare workers practicing in an HIV care and treatment program in western Kenya and to evaluate the effectiveness of a one-day neuro-HIV training module.

METHODS

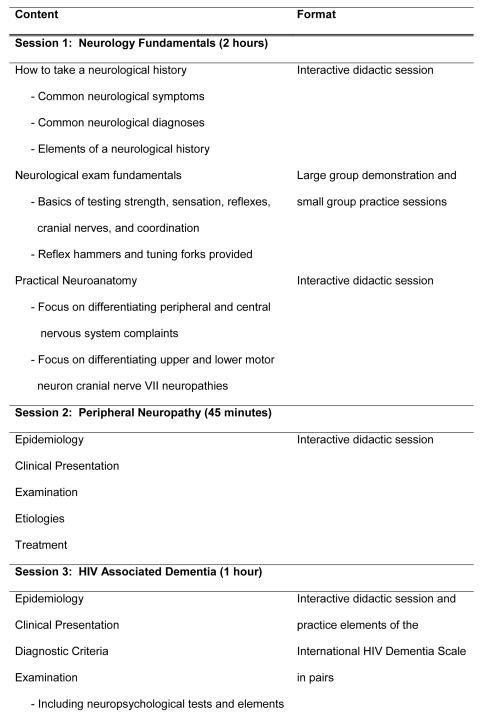

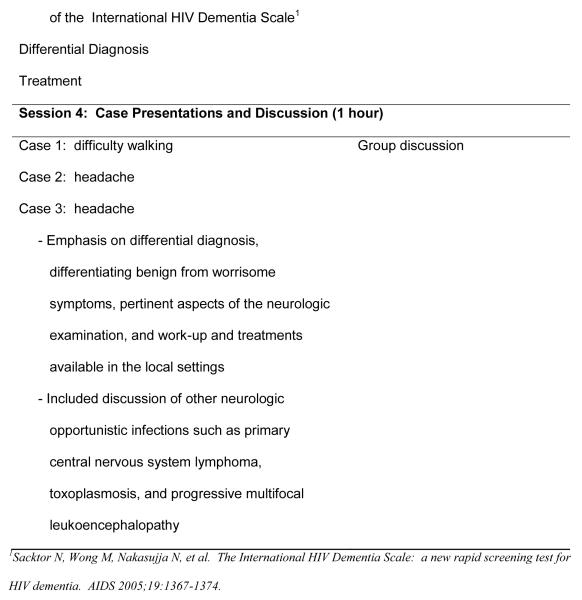

We developed a one-day training module for non-physician healthcare workers covering fundamentals of the neurologic examination, localization, diagnosis and treatment of neurologic complications of HIV, focusing specifically on HIV-associated dementia (HAD) and peripheral neuropathy (Figure 1). The training was comprised of didactic sessions, small group activities, and case studies. We invited 80 non-physician healthcare workers employed by or working in one of the 60 clinical sites supported for implementation of HIV care by Family AIDS Care and Education Services (FACES) in Nyanza province, Kenya. Training was provided in central locations at each of four districts within Nyanza province on four occasions in November and December 2009. Reimbursement for transport and housing was provided to participants who came from distant sites but no stipend was given for participation.

FIGURE 1.

Detailed content and format of the training sessions.

An anonymous baseline survey and pre- and post-tests were administered to participants who gave informed consent. The survey assessed demographic characteristics, clinical experience, and self-reported comfort treating a variety of medical and neurological conditions. Self-reported comfort was assessed using a 5 point Likert scale ranging from 0 (very uncomfortable) to 4 (very comfortable). Conditions were grouped into medical and neurological non-infectious and opportunistic infections (OI). Average scores were generated for each category. Comfort scores were compared using two-sample t-tests.

Knowledge testing consisted of identifying etiologies of peripheral neuropathy and diagnostic criteria for HAD from a list. For peripheral neuropathy, the number of correct and incorrect etiologies identified was measured. The HAD diagnostic criteria was scored as fully correct if participants identified the two correct criteria (impairment in ≥2 cognitive domains and impairment in activities of daily living) without selecting any incorrect criteria. Partially correct answers were those in which both correct diagnostic criteria were identified but also allowed for identification of one or more incorrect criteria. Pre- and post-test scores were compared using Fisher’s exact tests and t-tests.

Differences in comfort and test scores were assessed by level of medical training using one-way ANOVA and between rural versus urban practice location, and district headquarter versus peripheral site practice location using t-tests. Statistical analyses were done using Stata 10.0 (StataCorp, College Stations, Texas).

RESULTS

Of the 71 clinicians who attended the trainings, 55 (77%) consented to have their pre and post tests used for evaluation of the training module. The mean age of study participants was 29 years, and 56% (31/55) were male (Table 1). The majority of participants were clinical officers (29/55, 53%), healthcare workers who receive three to four years of post-secondary education and function similar to physician’s assistants in the United States. Nurses constituted an additional 40% (22/55) of the sample. On average, participants had been providing HIV care for 2.4 ± 3.3 years, and participants practicing primarily at rural sites made up 78% (43/55) of the study population.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants.

| Male [% (n)] | 56% (31) |

| Age [mean (SD)] | 29 (5) |

| Position [% (n)] | |

| Nurse | 40% (22) |

| Clinical Officer | 53% (29) |

| Medical Officer | 4% (2) |

| Medical Student | 4% (2) |

| Years caring for HIV patients [mean (SD)] | 2.4 (3.3) |

| Years working for FACES [mean (SD)] | 1.2 (1.2) |

| HIV+ patients seen per week [mean (SD)] | 154 (128) |

| Activities performed at least once per month [% (n)] | |

| HIV testing | 52% (28) |

| HIV counseling | 60% (33) |

| Initiate ARVs | 73% (40) |

| Monitor ARVs | 87% (48) |

| OI prophylaxis | 76% (42) |

| OI treatment | 80% (44) |

| Primary care | 65% (36) |

| Primary practice setting | |

| District Headquarters | 51% (28) |

| Peripheral Site | 42% (23) |

| Unknown | 7% (4) |

| Urban vs. rural practice location | |

| Urban | 22% (12) |

| Rural | 78% (43) |

Participants reported significantly more comfort treating all medical conditions as compared to all neurologic conditions (p<0.001) (Table 2). Similarly, participants were significantly more comfortable treating non-infectious medical conditions as compared to non-infectious neurologic conditions (p<0.001) and medical OIs as compared to neurologic OIs (p=0.005).

TABLE 2. Comparison of average scores for self-reported comfort for treating medical versus neurologic conditions.

Self reported comfort assessed using a 5 point Likert scale ranging from 0 (very uncomfortable) to 4 (very comfortable).

| Medicine | Average Score [mean (SD)] |

Neurology | Average Score [mean (SD)] |

Two sample T-test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All medical conditions | 3.2 (0.70) | All neurologic conditions | 2.1 (0.89) | <0.001 |

| Non-infectious conditions | 3.2 (0.67) | Non-infectious conditions | 2.1 (0.88) | <0.001 |

| Opportunistic infections | 3.1 (0.97) | Opportunistic infections | 2.5 (1.1) | 0.005 |

There was excellent baseline knowledge of the etiologies of peripheral neuropathy. Few incorrect etiologies of peripheral neuropathy were identified either before or after the training. Still, participants could name significantly more etiologies after the training (p<0.001) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of pre- and post-test scores after participating in a one day Neuro-HIV training module.

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etiologies of Peripheral Neuropathy | |||

|

| |||

| Correct Answers [mean (SD)]† | 5.6 (1.8) | 8.0 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Incorrect Answers [mean (SD)]‡ | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.33 (0.58) | 0.49 |

|

| |||

| Diagnostic Criteria for HIV Associated Dementia | |||

|

| |||

| Fully correct answer [% (n)] | 4% (2) | 6% (3) | 0.67 |

| Partially correct answer [% (n)] | 66% (33) | 72% (38) | 0.30 |

|

| |||

| Individual Items | |||

|

| |||

| Correct responses | |||

| Moderate impairment in ≥ 2 cognitive domains | 84% (42) | 87% (47) | 0.56 |

| Mild impairment in ≥ 2 cognitive domains | 28% (14) | 41% (22) | 0.2 |

| Moderate impairment of activities of daily living | 72% (32) | 79% (42) | 0.23 |

| Mild impairment of activities of daily living | 16% (8) | 53% (28) | <0.001 |

| Incorrect responses | |||

| Moderate impairment in one cognitive domain | 34% (17) | 24% (13) | 0.11 |

| Limb weakness | 38% (19) | 39% (21) | 1 |

| Abnormal level of consciousness | 82% (41) | 43% (23) | <0.001 |

| Hallucinations | 57% (28) | 15% (8) | <0.001 |

| History of central nervous system infection | 47% (23) | 30% (16) | 0.09 |

| Unsure | 12% (6) | 2% (1) | 0.049 |

p values calculated for the neuropathy portion were calculated using two-sample t-tests (otal possible correct answers=9; total possible incorrect answers=6.) p values for the dementia portion were calculated using Fischer’s exact tests.

Correct responses included diabetes, HIV, hepatitis C, syphilis, hypothyroidism, antiretroviral medications, isoniazid, vitamin B12 deficiency and vitamin B6 deficiency.

Incorrect responses included malaria, hepatitis B, chlamydia, hypoparathyroidism, Schistosomiasis, and vitamin C deficiency.

In contrast, there was poor knowledge of the diagnostic criteria for HAD prior to the training. After attending the training, there were no significant differences in the proportion of participants who gave fully correct (pre=4%; post=6%; p=0.67) or partially correct (pre=66%; post=72%; p=0.30) responses to the question about HAD diagnostic criteria (Table 3). Several incorrect diagnostic criteria were commonly identified on both the pre- and post-tests. Significantly fewer individuals identified abnormal level of consciousness (pre=82%; post=43%; p<0.001) and hallucinations (pre=57%, post=15%;p<0.001) as diagnostic criteria for HAD but no change was seen in the proportion identifying a history of central nervous system infection (pre=47%; post=30%; p=0.09) as an HAD diagnostic criterion.

No significant differences were seen in comfort scores, pre-test knowledge or post-test knowledge by level of medical training, rural versus urban practice location, or by practicing at a peripheral site versus a district headquarter were observed in any category (data not shown). In post-training qualitative evaluations, 26 (49%) participants requested either longer, more frequent or additional neurologic trainings.

DISCUSSION

Overall, our study clearly identified a need for neurologic training for health care workers providing primary care for HIV-infected patients and demonstrated that such trainings receive very positive responses. The clinicians in our study were significantly less comfortable treating common neurologic disorders as compared to general medical disorders. This was true even when comparing comfort treating neurologic versus medical OI. This finding is consistent with other studies of non-physician healthcare workers from sub-Saharan Africa who express discomfort diagnosing and treating neurologic disorders.24, 27

The self-reported discomfort with diagnosis and treatment of neurologic disorders is paired with a desire for training in neurology. Anecdotal reports from neurologists visiting or working in similar settings in sub-Saharan Africa have reported eagerness to take advantage of neurologic learning opportunities on the part of healthcare workers.28, 29 Similarly, the most common qualitative comments on evaluations of this training were requests to extend the length of the training, hold additional trainings, or provide additional training and mentorship during clinic visits for neurologic complaints.

Baseline knowledge of common neurologic disorders associated with HIV varied by disorder. For example, baseline knowledge of etiologies of peripheral neuropathy was quite good. In contrast, baseline knowledge of the diagnostic criteria for HAD was poor. Potential reasons for this discrepancy might be because diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy is more straightforward than diagnosis of HAD, because dementia is perceived to be less common in Kenya and, therefore, is not emphasized in the medical curriculum, or because of stigma around the diagnosis of dementia. Future work could include assessing and improving medical curricula in Kenya to ensure inclusion of cognitive disorders.

The effectiveness of the neuro-HIV training module we developed was mixed. Knowledge of peripheral neuropathy etiologies significantly improved and comfort managing neuropathy was very high after training. However, knowledge of the diagnostic criteria of HAD did not change significantly. After the training, few participants could provide fully correct answers to the diagnostic criteria for HAD. Although the majority of participants could provide partially correct answers after the training, and misconceptions about criteria for HAD were significantly reduced, many clinicians identified an abnormal level of consciousness, hallucinations or a history of a central nervous system infection as symptoms of HAD.

Reasons for the persistence of these misconceptions of the HAD diagnostic criteria may include different definitions of the terms “abnormal level of consciousness” or “hallucinations” held by the healthcare workers participating in our training and the study team. There may also be cultural associations between dementia and psychosis that will require more extensive training to dispel. It may also be that the HAD component of this training may not have been designed or presented effectively for our target audience. Finally, while the module itself may have had limited effect, it is possible that pairing the module with clinical mentorship would be effective at improving knowledge, recognition and clinical management of HAD.

Alternatively, it may be that the current diagnostic criteria for HAD are impractical for use in routine HIV care settings staffed primarily by clinical officers and nurses in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa. Both the Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Dementia Score and American Academy of Neurology (AAN) criteria for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders are based on highly specialized neuropsychological concepts such as impaired functioning in certain cognitive domains and formal evaluation of functional status. These definitions are useful in research and tertiary care settings with access to neurologists, neuropsychologists, and neuropsychological testing. However, neurologists and neuropsychologists are not available in most routine HIV care settings.

For example, as of June 2010, our study site at FACES served 87,730 patients with 25,666 patients on anti-retroviral therapy (ART). With the exception of the study team, there is no neurological consultation available at any of our care sites. Private consultation is available in a nearby city where one neurologist has one private clinic one day per month. However, the consultation fees are out of reach for most of our patients, and this clinic itself is several hours to one day’s travel from most of our clinic sites. Furthermore, no neuropsychological testing is available outside of the capital city Nairobi (several days travel from most of our clinic sites). Neuropsychological testing is only available privately and also out of reach for most of our patients. However, the treatment for HAD — initiating ART — is available at no cost at nearly all of our clinic sites.

Therefore, to improve recognition and treatment of neurocognitive disorders in routine HIV care settings staffed by non-physician healthcare workers, we strongly recommend developing a clinically relevant definition of HAD based on symptomatic presentation and simple screening tools. Brief screening tools, such as the International HIV Dementia Scale, have been developed for use in resource-constrained settings in response to this need and have demonstrated utility for detecting HIV-associated cognitive impairment when administered by trained physicians in settings where referral to a trained specialist is an option.13 However, non-physician healthcare workers are the primary care providers for the majority of HIV-infected individuals in Kenya. Trained physicians and specialists are not available to our patients.30 Thus, a standalone diagnostic tool or simple clinical criteria for diagnosing HAD is urgently needed. This is not intended to replace current research definitions such as the MSK score or AAN criteria, but, instead, to create a complementary definition for implementation in HIV care settings where the use of more sophisticated research definitions is not feasible or practical.

Our study has several limitations. Although we endeavored to make our sample of clinicians similar to others working in Africa, our sample consisted of healthcare workers employed by FACES, a collaboration between the Kenyan Medical Research Institute and the University of California – San Francisco, which has a strong focus on staff training, development, and mentorship. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to healthcare workers in other settings which do not share this focus on training. Second, attendance at the training was voluntary and no stipend was provided for participation, although travel reimbursement and housing was provided for individuals coming from distant sites. Therefore our sample of health care workers was subject to volunteer bias; our participants may have been more motivated to learn about HIV neurology than clinicians who did not volunteer. Additionally, we have not assessed long-term knowledge retention or evaluated whether the training improved the participants’ diagnosis or clinical management of neurologic complications of HIV in their routine clinical practice.

In summary, non-physician healthcare workers similar to participants in our study provide the bulk of neurologic care in Kenya in both general medical settings and HIV care and treatment programs. Our results provide further evidence that non-physician healthcare workers in sub-Saharan Africa feel uncomfortable treating neurologic disorders, that their baseline knowledge varies by disorder and that neurologic training is strongly desired. Although our training module for peripheral neuropathy appeared effective, further development and refinement of our training module on HAD is needed prior to widespread implementation. In addition, a clinical definition of HAD which takes into account the limited specialty services available in most primary HIV care settings in sub-Saharan Africa could improve recognition and treatment of HIV associated neurocognitive disorders. Creation and expansion of opportunities for neurologic training and further research into whether these trainings improve quality of care is urgently needed for the majority of patients in the developing world with limited or no access to neurologists in order to improve neurologic care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the medical officers, clinical officers, and nurses at FACES for their participation and the FACES administrative staff in Suba, Rongo, Migori and Kisumu districts for their invaluable logistical assistance in making these trainings possible.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT This study was supported by the Fulbright African Regional Research Program (Meyer), American Academy of Neurology Practice Research Training Fellowship (Meyer), and Doris Duke International Clinical Research Fellowship (Cettomai). In addition, this study was supported by the Fogarty International Clinical Research Fellowship (5 R24 TW00798; 3 R24 TW00798-02S1) (Meyer, Kwasa) from the National Institutes of Health, Fogarty International Center through Vanderbilt University, the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). We thank the Director of KEMRI for his support and permission to publish this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Owolabi MO, Bower JH, Ogunniyi A. Mapping Africa’s way into prominence in the field of neurology. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1696–1700. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.12.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson K, Kopnisky K, Hakim J, et al. Second assessment of NeuroAIDS in Africa. J Neurovirol. 2008;14:87–101. doi: 10.1080/13550280701829793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson KR, Hall CD. Assessment of neuroAIDS in the international setting. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2007;2:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson K, Kopnisky K, Mielke J, et al. Assessment of neuroAIDS in Africa. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(Suppl 1):7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandiah PA, Atadzhanov M, Kvalsund MP, Birbeck GL. Evaluating the diagnostic capacity of a single-question neuropathy screen (SQNS) in HIV positive Zambian adults. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:1380–1381. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.183210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maritz J, Benatar M, Dave JA, et al. HIV neuropathy in South Africans: frequency, characteristics, and risk factors. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:599–606. doi: 10.1002/mus.21535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadley AL, Cherry CL, Price P, Kamerman PR. HIV Neuropathy Risk Factors and Symptom Characterization in Stavudine-Exposed South Africans. J Pain Symptom Manage. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.006. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valcour V, Shikuma C, Shiramisu B, et al. Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals: the Hawaii Aging with HIV-1 Cohort. Neurology. 2004;63:822–827. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134665.58343.8d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Lorenzini P, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive impairment, 1996-2002: results from an urban observational cohort. Journal of Neurovirology. 2005;11:265–273. doi: 10.1080/13550280590952790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson D, Tagliati M. Neurologic manifestations of HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1994;121:769–785. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-10-199411150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maj M, Satz P, Janssen R, et al. WHO Neuropsychiatric AIDS Study: Neuropsychological and Neurological Findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:51–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Njamnshi A, Djientcheu V, Fonsah J, et al. The International HIV Dementia Scale Is a Useful Screening Tool for HIV-Associated Dementia/Cognitive Impairment in HIV-Infected Adults in Yaoundé--Cameroon. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2008;49:393–397. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318183a9df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sacktor N, Wong M, Nakasujja N, et al. The International HIV Dementia Scale: a new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS. 2005;19:1367–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howlett WP, Nkya WM, Mmuni KA, Missalek WR. Neurological disorders in AIDS and HIV disease in the northern zone of Tanzania. AIDS. 1989;3:289–296. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198905000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mbuya SO, Kwasa TO, Amayo EO, et al. Peripheral neuropathy in AIDS patients at Kenyatta National Hospital. East Afr Med J. 1996;73:538–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta SA, Ahmed A, Kariuki BW, et al. Implementation of a validated peripheral neuropathy screening tool in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Mombasa, Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:565–570. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cettomai D, Kwasa J, Kendi C, et al. Utility of quantitative sensory testing and screening tools in identifying HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy in Western Kenya: pilot testing. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwasa J, Cettomai D, Lwaynya E, et al. Testing a Diagnostic Tool for Primary Health Care Workers and Adapting Neuropsychological Tests for HIV-Associated Dementia in Kenya: Lessons Learned. PLoS One. Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. World Federation of Neurology . Atlas: Country Resources for Neurologic Disorders. Geneva: 2004. pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergen D. Training and distribution of neurologists worldwide. J Neurol Sci. 2002;198:3–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer A-C. Cettomai D, editor. Neurologists in Kenya. (Email ed) 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization . Global Health Atlas. 2002 ed Vol. 2011. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jowi JO. Provision of care to people with epilepsy in Kenya. East African Medical Journal. 2007:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birbeck GL. Barriers to care for patients with neurologic disease in rural Zambia. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:414–417. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bower JH, Zenebe G. Neurologic services in the nations of Africa. Neurology. 2005;64:412–415. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150894.53961.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergen D, Good D. Neurology training programs worldwide: A World Federation of Neurology survey. J Neurol Sci. 2006;246:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birbeck GL, Munsat T. Neurologic services in sub-Saharan Africa: a case study among Zambian primary healthcare workers. J Neurol Sci. 2002;200:75–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birbeck GL. A neurologist in Zambia. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:58–61. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dahodwala N. Neurology education and global health: my rotation in Botswana. Neurology. 2007;68:E15–16. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000257827.43171.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization . Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: global recommendations and guidelines. World Health Organization; [Accessed: 1 Sept 2010]. 2008. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/TTR-TaskShifting.pdf. [Google Scholar]