Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) plays an important role in several biological functions, including bronchial relaxation. Here, we have investigated the role of BNP and its cognate receptors in human bronchial tone.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Effects of BNP on responses to carbachol and histamine were evaluated in non-sensitized, passively sensitized, epithelium-intact or denuded isolated bronchi and in the presence of methoctramine, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) and aminoguanidine. Natriuretic peptide receptors (NPRs) were investigated by immunohistochemistry, RT-PCR and real-time PCR. Release of NO and acetylcholine from bronchial tissues and cultured BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells was also investigated.

KEY RESULTS

BNP reduced contractions mediated by carbachol and histamine, with decreased Emax (carbachol: 22.7 ± 4.7%; histamine: 59.3 ± 1.8%) and increased EC50 (carbachol: control 3.33 ± 0.88 µM, BNP 100 ± 52.9 µM; histamine: control 16.7 ± 1.7 µM, BNP 90 ± 30.6 µM); BNP was ineffective in epithelium-denuded bronchi. Among NPRs, only atrial NPR (NPR1) transcripts were detected in bronchial tissue. Bronchial NPR1 immunoreactivity was detected in epithelium and inflammatory cells but faint or absent in airway smooth muscle cells. NPR1 transcripts in bronchi increased after incubation with BNP, but not after sensitization. Methoctramine and quinine abolished BNP-induced relaxant activity. The latter was associated with increased bronchial mRNA for NO synthase and NO release, inhibited by L-NAME and aminoguanidine. In vitro, BNP increased acetylcholine release from bronchial epithelial cells, whereas NO release was unchanged.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Epithelial cells mediate the BNP-induced relaxant activity in human isolated bronchi.

Keywords: brain natriuretic peptide, natriuretic peptide receptor A, bronchodilatation, acetylcholine, nitric oxide, inducible NOS

Introduction

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), a member of the natriuretic peptide family is predominantly secreted by the cardiac ventricles (Mukoyama et al., 1991). BNP is elevated in patients with pulmonary disease, at least in those with concomitant right ventricular dysfunction such as primary pulmonary hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and left-to-right cardiac shunts, even in the absence of left ventricular failure (Mohammed and Januzzi, 2009). In patients with chronic pulmonary hypertension, an increase in BNP not only correlates with the degree of right ventricular dysfunction but also with the risk of mortality (Mohammed and Januzzi, 2009). Intriguingly, plasma BNP levels are elevated in patients with stable COPD without pulmonary hypertension or cor pulmonale (Inoue et al., 2009) and are increased in patients with COPD with normal right ventricular function after exercise (Gemici et al., 2008). In addition, plasma BNP levels are increased in some subjects with COPD undergoing exacerbations (Stolz et al., 2008). Unfortunately, the pathophysiological consequences of these elevated concentrations are not completely understood, although there is growing evidence that BNP plays an important role in several activities in the lung, such as bronchodilatation, pulmonary permeability and surfactant production (Hulks et al., 1990). Therefore, it might be hypothesized that high circulating levels of BNP released from the heart in states such as heart failure could have a modulating function on airway smooth muscle (ASM) tone (Matera et al., 2009).

BNP exerts its actions via binding to natriuretic peptide receptors (NPRs) located on the cell surface (Omland and Hagve, 2009; Potter et al., 2009). Three different NPRs (nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2009) have been identified: atrial NPR (NPR1), brain NPR (NPR2) and C-type NRP (NPR3). BNP binds to NPR1 with high affinity (Devillier et al., 2001). NPR1 contains an intracellular particulate guanylate cyclase (pGC) domain and this pGC catalyses the formation of cGMP, the downstream second messenger involved in most of BNP signalling (Potter et al., 2006). This cyclic nucleotide has many biological effects within the lung (Bianchi et al., 1985). The augmented availability of cGMP either by increased formation or inhibited degradation leads to relaxation of ASM and pulmonary vasculature cells (Potter et al., 2009).

At least in rats and cows, NPR1 is expressed in various tissues including the lung (Bianchi et al., 1985; Kawaguchi et al., 1989; Ishii et al., 1989) suggesting lung tissue might be a target organ for BNP. Although specific receptors for BNP have not been observed directly in human lungs, natriuretic peptides can induce relaxant effects on guinea pig, bovine and human ASM (Ishii and Murad, 1989; Hamad et al., 1997). In guinea pigs, BNP relaxes tracheal smooth muscle (Takagi et al., 1992) and prevents ovalbumin-induced bronchoconstriction and microvascular leakage (Ohbayashi et al., 1998). Moreover, the relaxant effect of BNP on isolated human bronchi, particularly after sensitization has been documented (Matera et al., 2009), suggesting that local factors regulate BNP action. This fits well with the finding that human recombinant BNP is a potent bronchodilator in asthmatic patients (Akerman et al., 2006). Nevertheless, data concerning the mechanisms through which BNP influences bronchial contractility are sparse. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to clarify the presence and functional localization of cognate receptors and the epithelium-dependent mechanisms regulating BNP-mediated relaxation in human isolated bronchi.

Methods

Tissue preparation

All human samples were obtained with full informed consent of the patients and with ethical approval from the Tor Vergata University Ethical Committee. Macroscopically normal bronchi, taken from an area as far as possible from the malignancy, were obtained from 12 patients (six male, six female, 52.1 ± 5.9 years old) undergoing pneumotomy or lobectomy surgery for cancer. Airways were immediately placed into oxygenated Krebs–Henseleit buffer solution (KH) (NaCl, 119.0 mM; KCl, 5.4 mM; CaCl2, 2.5 mM; KH2PO4, 1.2 mM; MgSO4, 1.2 mM; NaHCO3, 25.0 mM; glucose, 11.7 mM; pH 7.4) containing the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (5.0 µM), and transported at refrigerated condition. None of the patients had been chronically treated with a theophylline, β2-adrenoceptor agonists or glucocorticosteroids. Serum IgE levels at the day of surgery were within normal range. Human segmental bronchi (third generation bronchi), typically 3–5 mm in diameter were dissected from connective and residual lung tissue and cut into 2 mm rings. In some experiments, the bronchial epithelium was mechanically removed using a cotton-tipped applicator gently rubbed for 5 s on the luminal surface (Reinheimer et al., 1997). Successively, epithelial cells were collected for real-time PCR (see after) by gently scraping the luminal airway surface with a convex scalpel blade (Fulcher et al., 2005). It has been previously demonstrated that this manipulation does not penetrate the basal membrane and that the lamina propria remains almost intact (Reinheimer et al., 1996). Epithelium removal and the integrity of surrounding bronchial layers were confirmed by histology.

Passive sensitization

The passive sensitization of isolated bronchial rings is a model that closely mimics important characteristics of airway hyper-responsiveness in vivo. Therefore, this model was used to study the anti-spasmogenic effect of BNP in human hyper-reactive bronchi (Schmidt et al., 2000). Samples were incubated overnight with rotation at room temperature in tubes containing KH buffer solution in the absence (non-sensitized control rings) or presence of 10%·by volume of sensitizing serum (sensitized rings). The serum was prepared by centrifugation from the whole blood of patients suffering from atopic asthma (total IgE > 250 U·mL−1 specific against common aeroallergens) during exacerbation (Watson et al., 1997; Rabe, 1998). Sera were frozen at −80°C in 200 mL aliquots until required. The next morning, after removal of adhering alveolar and connective tissues, bronchial rings were transferred into an organ bath containing KH buffer (37°C) and continuously gassed with a 95:5% mixture of O2 and CO2.

Tension measurement

Bronchial rings into the organ bath were connected to an isometric force displacement transducer Fort 10 WPI (Basile Instruments, Italy). Tissues were mounted on hooks, and attached with thread to a stationary rod and the other tied with thread to an isometric force displacement transducer. Airways were allowed to equilibrate for 90 min washing with fresh KH buffer every 10 min. Passive tension was determined by gentle stretching of tissue (0.5–1.0 g) during equilibration. The isometric change in tension was measured by the transducer and the tissue responsiveness assessed by adding acetylcholine (100 µM). When the response reached plateau, rings were washed three times and allowed to equilibrate for 45 min.

Study design on isolated organ bath

In isolated control bronchial rings, concentration-contraction curves to carbachol and histamine (100 nM–1 mM) were constructed, applying consecutive and cumulative injections when the contractions reached a plateau. After 90 min equilibration, with washing (10 mL) every 10 min, samples were incubated for 45 min with BNP at 1 µM, a concentration that induces the maximal relaxation in human isolated bronchi, followed by three washes (10 mL) in 10 min; then the concentration-contraction curves to carbachol and histamine (100 nM–1 mM) was repeated (Matera et al., 2009). BNP was present in the isolated organ bath solution before and during the exposure to the spasmogens. In order to evaluate the role of muscarinic M2 receptor subtypes or NO on the BNP effect, the basic protocol was also carried out on airways pre-incubated with an antagonist of M2 muscarinic receptors, methoctramine (100 nM concentration) and with the NO synthase (NOS) inhibitor L-NAME (1 mM) or the inhibitor of inducible NOS (iNOS) aminoguanidine (100 µM), all 15 min before BNP incubation. Control experiments were carried out in order to assay the effects of L-NAME and aminoguanidine on carbachol and histamine-elicited contractions in the absence of BNP. In order to assess if the effects of BNP were coupled to the bronchial non-neuronal release of acetylcholine, experiments on human isolated airways treated with quinine (100 and 500 µM), an inhibitor of organic cation transporters that reduces acetylcholine release, were carried out (Arndt et al., 2001; Wessler et al., 2001; Lips et al., 2005; Schlereth et al., 2006). The concentrations of antagonists or inhibitors were chosen on the basis of their IC50, binding affinities (Ki) or pA2 values, as previously reported (Wess et al., 1988; Delmendo et al., 1989; Aas and Maclagan, 1990; Tamaoki et al., 1995; Alderton et al., 2001; Arndt et al., 2001; Wessler et al., 2001; Lips et al., 2005; Gosens et al., 2006; Schlereth et al., 2006).

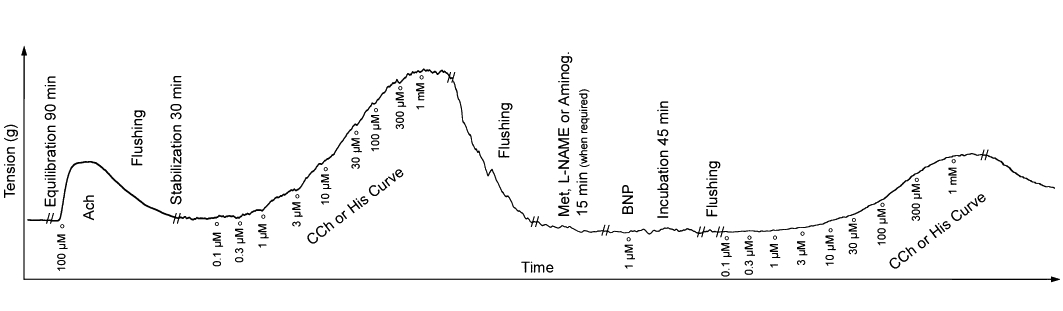

The basic protocol was also repeated on epithelium-intact and epithelium-removed bronchi, in non-sensitized and passively conditions. Further experimental details of the protocol are shown in Figure 1. There was no significant difference between epithelium-intact or epithelium-denuded, non-sensitized or passively sensitized human bronchial rings, either in wet weight or in the contraction induced by acetylcholine (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Typical experimental record from studies with brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) on rings of human isolated bronchi in an organ bath system. //Indicates a break in the record for the time shown. Aminog, aminoguanidine; CCh, carbachol, His, histamine; Met, methoctramine.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of isolated bronchial rings

| Non-sensitized | Passively sensitized | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP+ | EP− | EP+ | EP− | |

| Wet weight (mg) | 175 ± 6.85 | 170 ± 7.10 | 182 ± 8.83 | 178 ± 9.55 |

| Acetylcholine contraction (g) | 0.87 ± 0.13 | 0.89 ± 0.09 | 0.90 ± 0.13 | 0.93 ± 0.19 |

| Carbachol EC50 (µM) | 3.13 ± 0.87 | 1.35 ± 0.15 | 7.05 ± 1.78 | 3.08 ± 1.18 |

| Histamine EC50 (µM) | 16.68 ± 1.60 | 2.59 ± 0.30 | 4.55 ± 0.03* | 4.70 ± 0.32†° |

Values shown are the mean ± SEM from experiments performed with samples of n = 9 different subjects.

P < 0.05 versus non-sensitized EP+.

P < 0.05 versus non-sensitized EP−. EP+, epithelium-intact bronchial rings; EP−, epithelium-denuded bronchial rings.

The potential relaxant effect of acetylcholine was assessed in both epithelium-intact and epithelium-denuded bronchial rings contracted with histamine (at its EC50 dose (3.0 ± 1.8 µM) and allowed a 15 min stabilization period. After that, concentration-contraction curves were constructed to acetylcholine (0.1 pM–1 µM). Each concentration–response curve was obtained by the cumulative addition of acetylcholine at intervals of 10–15 min to reach a stable level of relaxation before the next addition was made. At the end of the experiments papaverine (500 µM) was added to determine the maximal relaxant response achievable for each isolated bronchial ring. Experiments on relaxation were repeated pretreating bronchial rings for 15 min with methoctramine (100 nM) or aminoguanidine (100 µM). Control epithelium-intact and epithelium-denuded bronchi contracted with histamine were also studied.

Microscopic and immunohistochemical investigation

After pharmacological stimulation, bronchial rings were divided in 1–2 mm thick sections and frozen in isopentane cooled by liquid nitrogen, or fixed for 24 h in buffered formalin (10%) and embedded in paraffin for morphological studies. Serial paraffin sections (4 µm thick)were stained with haematoxylin-eosin or used for immunohistochemical assays (Orlandi et al., 2006). In the latter, antigen retrieval with 10 mM sodium citrate buffer in a bath at 98°C, non-specific immunoglobulin binding blocking was performed with normal goat serum. Rabbit polyclonal anti-NPR1 (1:750, 1 h; ab14356, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used as primary antibody, followed by biotin-labelled secondary goat anti-rabbit (1:40, GRB005; YLEM, Avezzano, Italy) for 30 min, and by a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:100, YLEM) for 30 min. Human myocardial tissue, normal tissue from lung specimens of our surgical archive and bronchial sections without primary antibody incubation were included as controls. Bound antibody was revealed with the use of the substrate 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as chromogen. All procedures were performed at room temperature. Slides were counterstained with haematoxylin.

Determination of acetylcholine and NO release

BEAS-2B cells, derived from human bronchial epithelium (a gift from L. Petecchia, Pulmonary Diseases Unit. G, Gaslini Institute, Genoa, Italy), were cultured with a 1:1 mixture of LHC-9 (Gibco) and RPMI 1640 medium (EuroClone; Milan, Italy). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. BEAS-2B cells were seeded at a density of 1400·cells cm−2, maintained in culture and treated, at 80% of confluence, with 1 µM BNP for 1 h. In control cultures, substitution with fresh medium was performed. After treatment, the bath solution of isolated bronchi and BEAS-2B culture medium were collected and acetylcholine and NO metabolite (as nitrate and nitrite) were assayed with Acetylcholine/Choline quantification (BioCat; Heidelberg, Germany) and colorimetric assay kits (BioVision; CA, USA), respectively, at 570 or 540 nm in 96-well plates, according to manufacturers' instructions, with triplicate samples.

MTT assay

In order to verify any cytotoxic effect of BNP, the 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was performed as previously reported (Pisano et al., 2010). Cytotoxic potency evaluated by the ‘ALLFIT’ computer program showed that BNP at 1 µM was not cytotoxic in BEAS-2B cultures.

Reverse transcriptase- and real-time-polymerase chain reaction

Frozen bronchial rings and epithelial bronchial cells were homogenized and pooled total RNA extracted by using TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen), as previously reported (Orlandi et al., 2007). Qualitative gene expression profile of human NPR subtypes (NPR1, NPR2, NPR3), and iNOS, was checked by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (Orlandi et al., 2007) using human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase as housekeeping gene. The primer pairs are listed in Table 2. Gene expression of NPR1 and iNOS was also analysed by real-time PCR (iQ5, Bio-Rad) with iQ™ SYBR® green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Italy); β2-microglobulin and cyclophilin A were used as housekeeping genes (Orlandi et al., 2007). The results were reported as normalized fold expression. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated twice.

Table 2.

Primers sequences for polymerase chain reaction

| Gene | Primer sequences | Temperature of annealing | Amplicon length (bp) | N°. Acc. GenBank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPR1 | Forward 5′;-GCA AAG GCC GAG TTA TCT ACA TC-3′ | 65°C | 98 | NM_000906 |

| Reverse 5′-AAC GTA GTC CTC CCC ACA CAA-3′ | ||||

| NPR2 | Forward 5′-CGG GAG GAT GGA CTT CGA-3′ | 60°C | 75 | NM_000907 |

| Reverse 5′-CAT GAC AAC CAG CCC AGT TAC A-3′ | ||||

| NPR3 | Forward 5′-GGA AGA CAT CGT GCG CAA TA-3′ | 60°C | 79 | M59305 |

| Reverse 5′-GAT GCT CCG GAT GGT GTC A-3′ | ||||

| iNOS | Forward 5′-CCC CAT CAA GCC CTT TAC TT-3′ | 60°C | 182 | NM_000625 |

| Reverse 5′-CAC CTC CTG GTG GTC ACT T-3′ | ||||

| GAPDH | Forward 5′-ACG GAT TTG GTC GTA TTG G-3′ | 60°C | 230 | NM_002046 |

| Reverse 5′-GAT TTT GGA GGG ATC TCG C-3′ | ||||

| β2-microglobulin | Forward 5′-GAT TCA GGT TTA CTC ACG TC-3′ | 62°C | 232 | AF072097 |

| Reverse 5′-GTT CAC ACG GCA GGC ATA CT-3′ | ||||

| Cyclophilin A | Forward 5′-CAT GGT CAA CCC CAC CGT GTT CTT-3′ | 60°C | 237 | NM_021130 |

| Reverse 5′-TAG ATG GAC TTG CCA CCA GTG CCA T-3′ |

NPR1, atrial natriuretic peptide receptor; NPR2, brain natriuretic peptide receptor; NPR3, C-type natriuretic peptide receptor.

Data analysis

Appropriate curve-fitting to a sigmoidal model was used to calculate the effect (E), the maximal response (Emax) and the EC50. The equation used was log(agonist) versus response, Variable slope, expressed as Y = Bottom + (Top−Bottom)/{1 + 10^[(LogEC50−X)*HillSlope]} (Motulsky and Christopoulos, 2004; Goodman et al., 2007). E/Emax was expressed as percentage of Emax elicited by carbachol or histamine; EC50 values were converted to negative logarithmic values (pD2) for statistical analysis although only EC50 values are given in the text for easier comprehension (Goodman et al., 2007). All values are presented as mean ± SEM of six subjects for each treatment group. Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t-test or one-way or two-way anova, with Dunnett's or Bonferroni post-tests respectively. All data analyses were performed using computer software (GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The level of statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 (Motulsky, 1995).

Materials

The following drugs were used: acetylcholine, carbachol, histamine, methoctramine, Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME), aminoguanidine, indomethacin, quinine, papaverine and BNP. All substances were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Drugs were dissolved in distilled water except for indomethacin and quinine, which was dissolved in ethanol and then diluted with KH solution. The maximal amount of ethanol (0.02%) did not influence isolated tissue response (Freas et al., 1989; Hatake and Wakabayashi, 2000). Compounds were stored in small aliquots at −80°C until their use.

Results

Baseline characteristics of bronchial rings

There was no difference in the EC50 to carbachol, using the concentration-contraction curves, between non-sensitized and passively sensitized epithelium-intact bronchi or between non-sensitized and passively sensitized epithelium-denuded bronchi. Significant differences (P < 0.05) were detected in EC50 values for histamine contractions between non-sensitized and passively sensitized epithelium-intact bronchi and non-sensitized and passively sensitized epithelium-denuded bronchi, as previously reported (Rabe, 1998) (Table 1).

Effects of BNP on concentration-contraction curves for carbachol and histamine

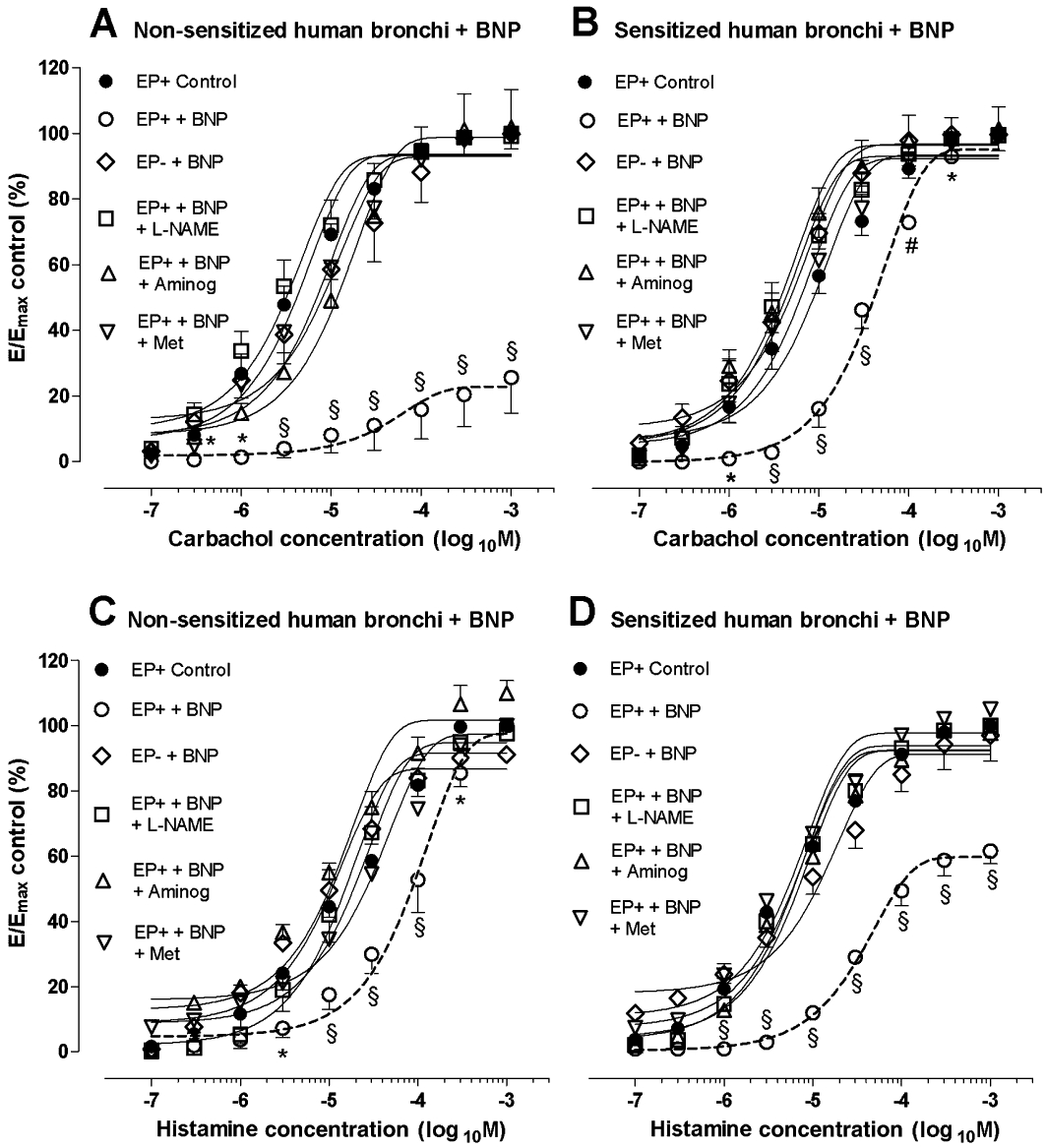

Incubation of epithelium-intact human bronchi with BNP induced a significant shift to the right of the carbachol concentration-contraction curves compared with controls (Figure 2A), with a decrease of Emax (P < 0.001) and an increase in the EC50 value (P < 0.01; Table 3A). In passively sensitized bronchi (Figure 2B), BNP produced a shift to the right of the carbachol concentration-contraction curves, compared with controls and increased EC50 values (P < 0.05), with no changes in the Emax value. Incubation with BNP also shifted the histamine concentration-contraction curves to the right, compared with control (Figure 2C) and enhanced EC50 (P < 0.01) without changing the Emax value (Table 3A); in passively sensitized bronchial rings (Figure 2D) BNP shifted to the right the histamine concentration-contraction curves (P < 0.05), increased EC50 and reduced Emax value (P < 0.001). As reported in Table 3B, BNP incubation of epithelium-denuded isolated bronchi did not induce significant differences on either carbachol or histamine concentration-contraction curves compared to the epithelium-denuded control, either in non-sensitized or sensitized bronchi. Accordingly, the EC50 in response to BNP in epithelium-denuded bronchi was reduced both in non-sensitized and passively sensitized bronchi compared to epithelium-intact bronchi (P < 0.05; Table 3). Furthermore, the Emax was significantly increased in non-sensitized, epithelium-denuded, carbachol-contracted (P < 0.001), as well as in passively sensitized, epithelium-denuded, histamine-contracted bronchi (P < 0.001), indicating that epithelium-denuded bronchi were similar to non-incubated bronchi, in their response to BNP.

Figure 2.

Effects of BNP on concentration-contraction curves for (A,B) carbachol and (C,D) histamine. Influence of epithelium removal, L-NAME, aminoguanidine and methoctramine in (A,C) non-sensitized and in (B,D) passively sensitized bronchi. Data shown (mean ± SEM) are from experiments performed with samples from 4 different subjects. *P < 0.05, #P < 0.01, §P < 0.001 significantly different from control group. Aminog, aminoguanidine; E, effect; EP+, epithelium-intact; EP-, epithelium-denuded; Emax, maximal response; Met, methoctramine.

Table 3.

(A) Effects of BNP incubation and pretreatment of methoctramine, L-NAME and aminoguanidine on contraction concentration-curves to carbachol and histamine in human isolated epithelium-intact bronchi. (B) Effects of BNP on contraction concentration-curve to carbachol and histamine in human isolated epithelium-denuded bronchi

| Carbachol | Histamine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Epithelium-intact human bronchial rings | Non-sensitized | Passively sensitized | Non-sensitized | Passively sensitized | ||||

| Emax (%) | EC50 (µM) | Emax (%) | EC50 (µM) | Emax (%) | EC50 (µM) | Emax (%) | EC50 (µM) | |

| Control | 93.58 ± 2.51 | 3.33 ± 0.88 | 93.68 ± 3.01 | 7.00 ± 1.73 | 94.94 ± 3.35 | 16.70 ± 1.67 | 92.35 ± 2.44 | 4.53 ± 0.03 |

| BNP | 22.74 ± 4.65§ | 100.00 ± 52.90# | 95.46 ± 2.46 | 33.30 ± 6.67* | 97.62 ± 4.71 | 90.00 ± 30.60# | 59.25 ± 1.82§ | 33.30 ± 3.33§ |

| BNP + methoctramine | 93.49 ± 2.54 | 5.67 ± 0.82 | 93.94 ± 2.89 | 7.67 ± 1.86 | 94.46 ± 2.43 | 23.30 ± 3.33 | 92.62 ± 2.46 | 5.33 ± 0.33 |

| BNP + L-NAME | 93.16 ± 2.99 | 3.67 ± 0.88 | 93.35 ± 2.91 | 4.33 ± 2.08 | 91.75 ± 2.74 | 11.00 ± 7.81 | 93.74 ± 2.09 | 4.67 ± 0.33 |

| BNP + aminoguanidine | 98.74 ± 4.44 | 7.67 ± 2.33 | 96.72 ± 3.18 | 4.00 ± 1.72 | 101.8 ± 3.55 | 10.33 ± 2.40 | 92.23 ± 2.23 | 5.33 ± 0.58 |

| (B) Epithelium-denuded human bronchial rings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 93.39 ± 2.71 | 1.33 ± 0.16 | 95.61 ± 3.50 | 3.00 ± 1.15 | 96.04 ± 2.18 | 2.67 ± 0.33 | 92.68 ± 2.96 | 4.67 ± 0.33 |

| BNP | 92.96 ± 4.76 | 8.00 ± 8.50 | 97.02 ± 1.86 | 4.17 ± 0.92 | 94.83 ± 2.95 | 5.67 ± 2.33 | 86.19 ± 3.79 | 9.83 ± 5.42 |

Values shown are the mean ± SEM from experiments performed with samples from at the least 4 different subjects.

P < 0.05 versus control.

P < 0.01 versus control.

P < 0.001 versus control.

Influence of methoctramine, L-NAME, aminoguanidine and quinine on BNP-dependent contraction–concentration curve of carbachol and histamine

To investigate downstream mechanisms of BNP-dependent bronchial tone regulation, we used the M2 muscarinic receptor antagonist, methoctramine, an NOS inhibitor, L-NAME and the inhibitor of iNOS, aminoguanidine. Pre-incubation with methoctramine (100 nM), L-NAME (1 mM) or aminoguanidine (100 µM) for 15 min, completely antagonized the effects of BNP on concentration-contraction curves for carbachol and histamine in both non-sensitized and passively sensitized epithelium-intact bronchi (P < 0.01; Table 3A and Figure 2).

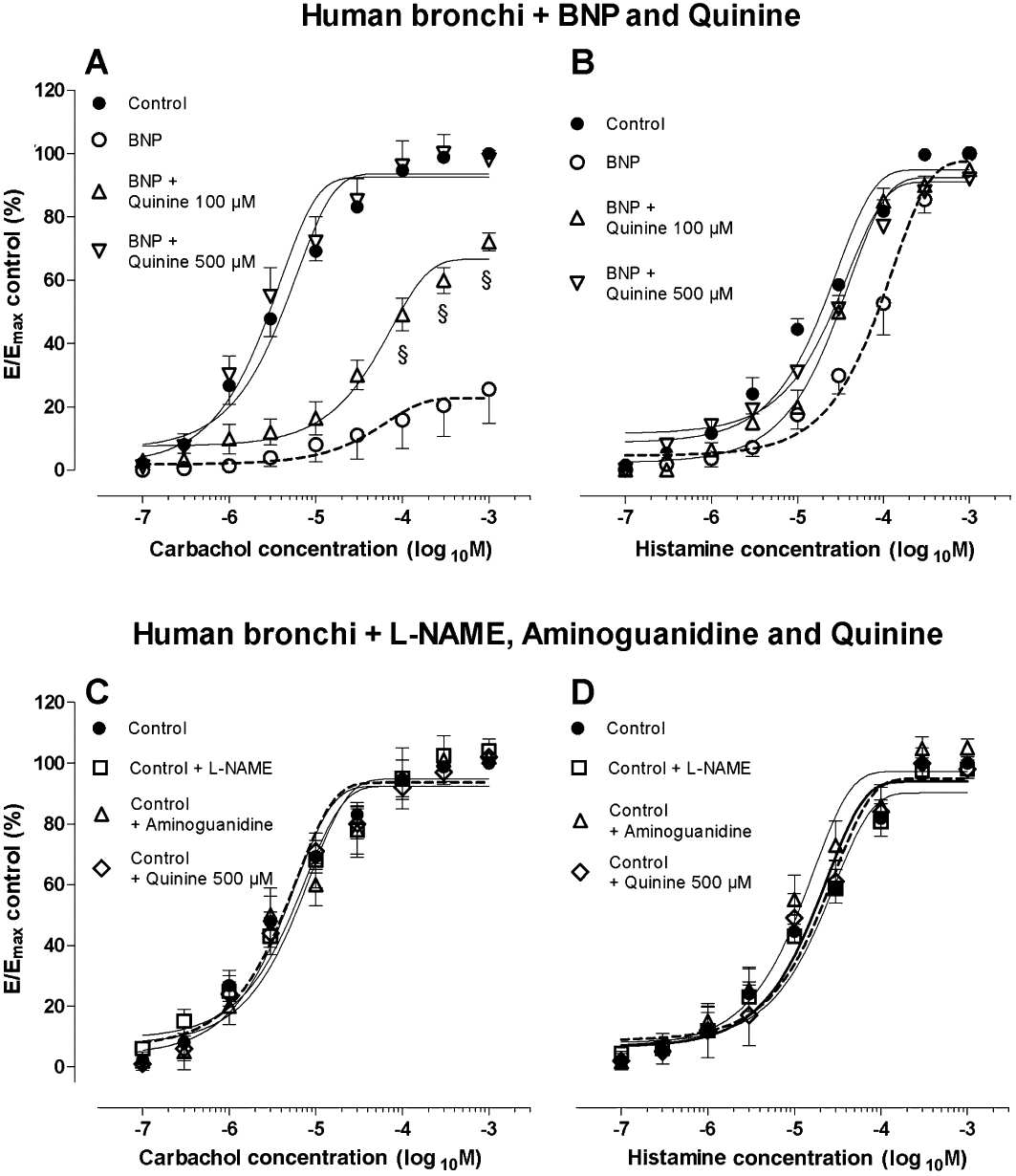

In epithelium-intact bronchi contracted with carbachol, the inhibitor of acetylcholine release, quinine, partially reduced the effect of BNP at 100 µM whereas, at 500 µM, it completely inhibited the relaxation to BNP (P < 0.001). Furthermore, quinine (100 µM) significantly (P < 0.001) antagonized the effects of BNP on concentration-contraction curves for histamine. As shown in Figure 3, in the absence of BNP, neither L-NAME, aminoguanidine nor quinine altered the bronchial contraction to carbachol and histamine, as previously reported in guinea-pig trachea (Sasaki et al., 1995).

Figure 3.

Effects of BNP on concentration-contraction curves for (A) carbachol and (B) histamine and influence of quinine (100 and 500 µM) treatment. Effects of L-NAME, aminoguanidine and quinine on concentration-contraction curves for (C) carbachol and (D) histamine in the absence of BNP. All experiments (A–D) were carried out in epithelium-intact human isolated bronchi. Data shown (mean ± SEM) are from experiments performed with samples from 3 different subjects. §P < 0.001 significantly different from BNP treatment. E, effect; Emax, maximal response.

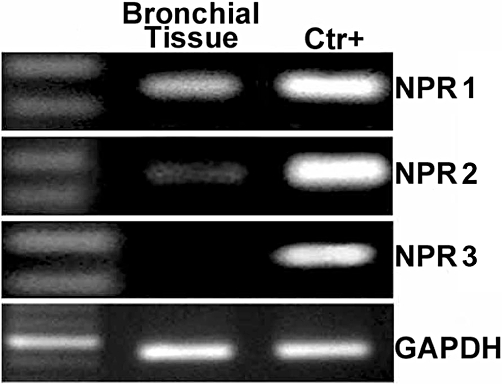

Human NPR expression in human bronchi

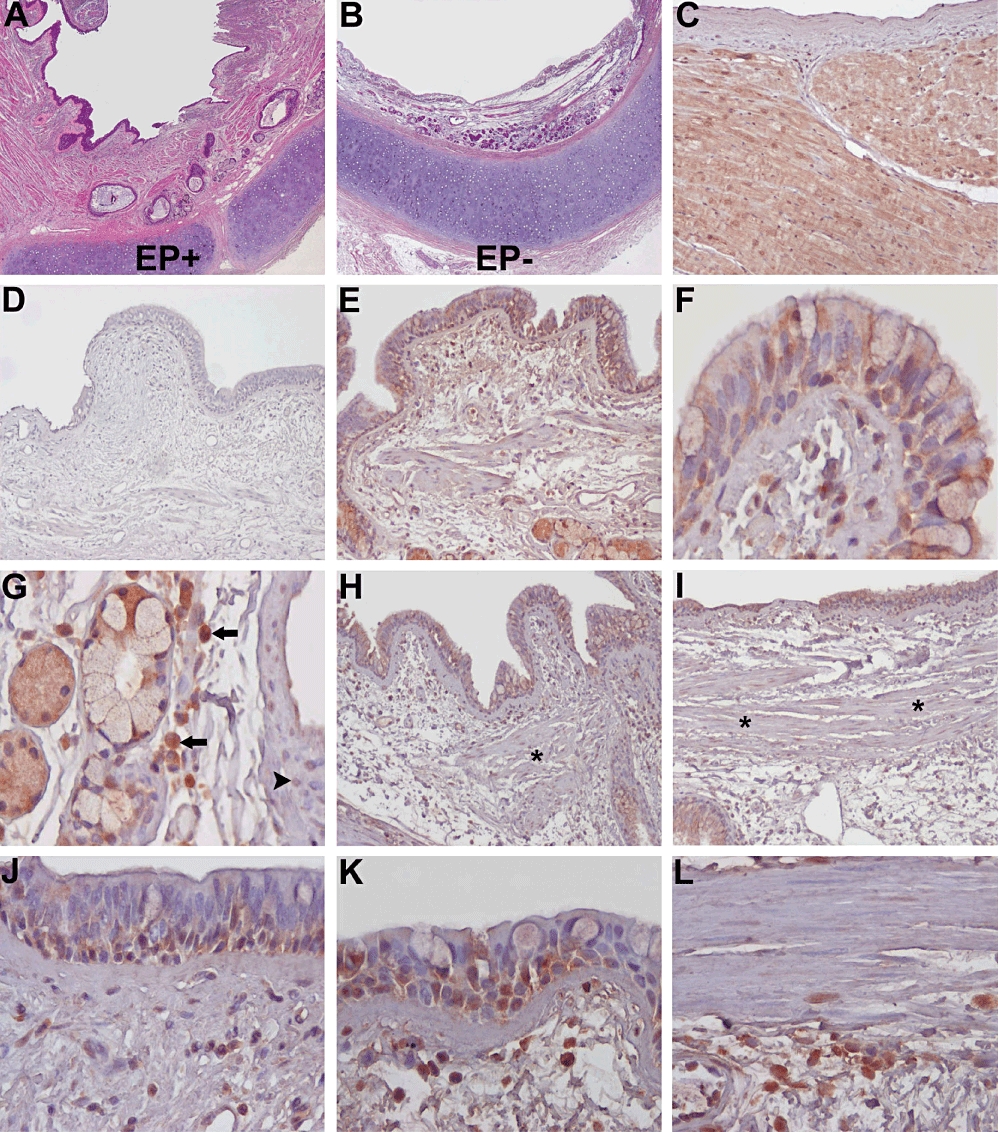

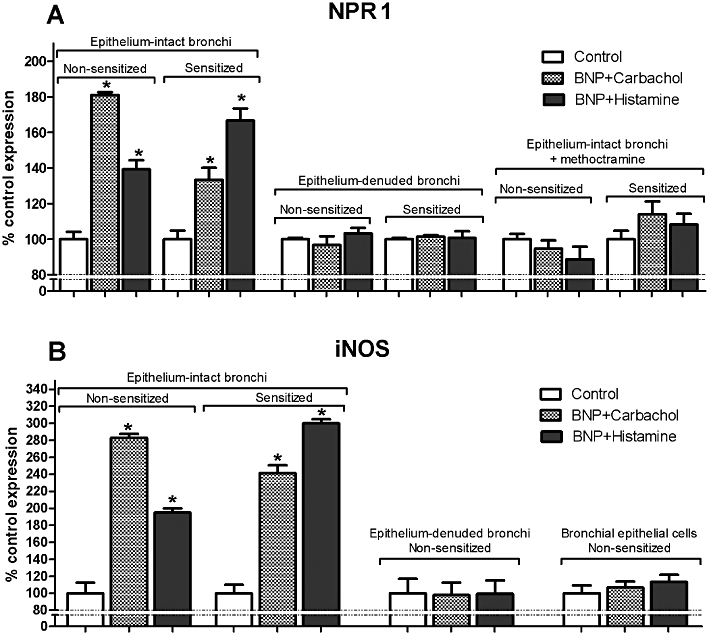

Assays with RT-PCR (Figure 4) showed that NPR1 transcripts were significantly expressed in isolated human bronchial tissue, whereas NPR2 and NPR3 transcripts were barely detected or absent. Real-time PCR analysis confirmed results obtained by RT-PCR. To investigate bronchial NPR1 distribution, we used immunohistochemistry. As illustrated in Figure 5, NPR1 immunoreactivity was detected in bronchial epithelium, except in goblet cells; the same was true for glandular epithelium. Inflammatory cells in the lamina propria also showed discrete NPR1 immunoreactivity. However, the latter was barely detected in the underlying bronchial smooth muscle cells. NPR1 immunoreactivity distribution and the amount of inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria were similar in all experimental groups, as well as in bronchial specimens from routine post-surgical pathological lung examinations.

Figure 4.

Expression of natriuretic peptide receptors (NPRs) in bronchial tissue. Representative gene expression of NPRs in human bronchial tissue by RT-PCR using as positive controls myocardium for atrial NPR (NPR1) and C-type NPR (NPR3), lung tissue for brain NPR (NPR2) and GAPDH as housekeeping gene. All bronchi were epithelium-intact.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical detection of NPR1 in isolated human bronchi. Microscopic appearance after haematoxylin-eosin staining of human isolated bronchi with (A) intact epithelium and (B) after mechanical removal of surface epithelium. (C–I) Anti-NPR1 antibody was used for detection in adult human bronchial sections, using (C) atrial myocardium and (D) human bronchial sections without primary antibody as positive and negative control respectively. (E) NPR1 immunoreativity in control bronchial epithelium; at higher magnification, (F) NPR1 is variably detected in ciliated as well in basal cells, but not in goblet cells. Also (G) glandular serous cells in the lamina propria are NPR1 positive, as well as inflammatory cells of the lamina propria (arrow) but not adjacent vascular smooth muscle cells (arrow head). Similarly, epithelial cells in bronchial rings incubated with BNP plus carbachol (H) or histamine (I) are NPR1 positive, while immunoreactivity of submucosal smooth muscle cells (*) is faint. At higher magnification (J) NPR1 immunostaining of bronchial epithelium incubated with BNP alone or (K) BNP plus carbachol with (L) underlying submucosal smooth muscle. Original magnification: A,B: ×20; C–E,H,I: ×125; F,G,J–L: ×400.

Pharmacological modulation of NPR expression

To investigate early modulation of NPRs in response to the pharmacological induction, we used RT and real-time PCR. No differences were detected in NPR1 transcript levels between non-sensitized and passively sensitized bronchi (Figure 6A). After 30 min of treatment with 1 mM carbachol or histamine, NPR1 transcripts were increased (P < 0.05) compared with respective controls in both BNP-incubated non-sensitized and passively sensitized bronchi. Neither carbachol nor histamine induced significant changes in NPR1 transcripts in non-sensitized or in passively sensitized epithelium-denuded bronchi compared with respective controls. Furthermore, pretreatment with methoctramine abolished the increase in NPR1 levels in both non-sensitized and passively sensitized bronchi, suggesting that antagonizing M2 muscarinic receptors acts as a negative feedback loop in the NPR1 transcriptional pathway in bronchial smooth muscle. In addition, neither carbachol nor histamine modulated NPR2 or NPR3 transcript level. NPR1 transcripts were also documented in BEAS-2B cells (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Transcripts of NPR1 and iNOS by real-time PCR in isolated human bronchi (non-sensitized and passively sensitized) and in bronchial epithelial cells (non-sensitized) treated with BNP and stimulated with carbachol or histamine: influence of epithelium removal and methoctramine. Values (shown as control = 100%) are the mean ± SEM from 3 different bronchial samples. *P < 0.05 significantly different from control group.

iNOS activity and BNP-dependent contraction of human bronchi

To further investigate downstream regulatory mechanisms of BNP-dependent bronchorelaxation, we analysed iNOS mRNA expression. As shown in Figure 6B, the maximal BNP-dependent relaxant activity was coupled to the increase of iNOS transcript levels both in non-sensitized and in sensitized human bronchi, whereas iNOS transcript level did not change in epithelium-denuded bronchi or in bronchial epithelial cells isolated by scraping, compared to control, strongly suggesting that relaxant activity was not due to epithelial NO production.

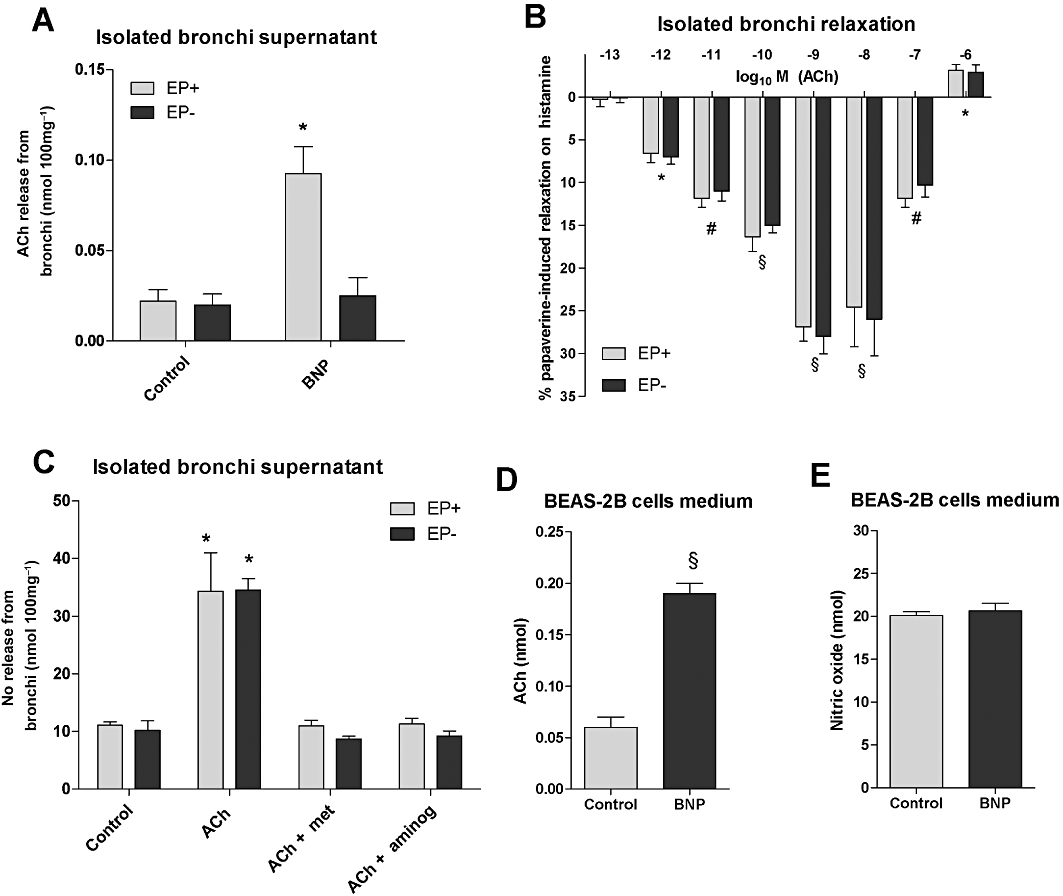

BNP-mediated release of acetylcholine and bronchial relaxation

Treatment with BNP (1 µM) significantly modulated release of acetylcholine into the supernatant, in epithelium-intact bronchi (P < 0.05) but not in epithelium-denuded bronchi (P > 0.05) compared with controls (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Levels of acetylcholine (Ach, nmol per 100mg of ring) in supernatant of isolated organ bath containing human bronchi after stimulation with BNP (A). Concentration-dependent relaxant effect of acetylcholine on histamine-induced contraction (EC50) in epithelium-intact and epithelium-denuded bronchial rings (B). Levels of NO (nmol per 100mg of ring) in supernatant of isolated organ bath containing human bronchi stimulated with acetylcholine at low concentrations (pM-nM) and blocking muscarinic M2 receptors with methoctramine (Met) or iNOS with aminoguanidine (Aminog) (C). Levels of acetylcholine (D) and NO (E) in BEAS-2B cell medium after stimulation with BNP. Data shown (mean ± SEM) are from experiments performed with samples from 3 different subjects (A,B) or in triplicate (C,D). (A) *P < 0.05, # P < 0.01, §P < 0.001 significantly different from histamine-contracted control bronchi baseline (not shown); (B–D) *P < 0.05, §P < 0.001 significantly different from controls. EP+, epithelium-intact; EP-, epithelium-denuded.

Furthermore, acetylcholine (1pM-100nM) induced a significant (P < 0.001) relaxant activity on histamine-contracted bronchial rings, compared to control (Figure 7B). This relaxant effect was similar in both epithelium-intact and epithelium-denuded bronchi ((pD2: epithelium-intact 10.55 ± 0.30, epithelium-denuded 10.30 ± 0.29) and it was completely converted to a contractile effect at the highest concentration of acetylcholine (1 µM) (Figure 7B). Furthermore, pretreatment for 15 min with methoctramine (100 nM) or aminoguanidine (100 µM) completely abolished the relaxant effect of acetylcholine, in both epithelium-intact and epithelium-denuded bronchial rings (P > 0.05 vs. control).

Modulation of NO and acetylcholine release in human isolated bronchi and BEAS-2B cells

In human isolated bronchi pre-contracted with histamine, acetylcholine ((1pM-100nM) increased (P < 0.05) the levels of NO metabolites in the bath solution, in both epithelium-intact and epithelium-denuded bronchi, compared to control(Figure 7C). The acetylcholine-induced NO modulation was epithelium independent (P > 0.05, epithelium-intact vs. epithelium-denuded) and it was completely abolished (P > 0.05 vs. control) by pretreatment with methoctramine or aminoguanidine, compared with control (Figure 7C).

Treatment with BNP (1 µM) for 1 h induced a significant (P < 0.001) release of acetylcholine in the medium of BEAS-2B cells, compared with control. On the contrary, BNP did not modulate NO release from BEAS-2B cells compared with control (Figure 7D,E).

Discussion

Our results show that incubation of human bronchial smooth muscle with BNP inhibited constriction induced by cholinergic and histaminergic stimulation. Moreover, epithelium integrity was crucial for BNP-mediated relaxant functional activity in human isolated bronchi. In fact, immunohistochemical investigation showed that NPR1 is diffusely present in bronchial epithelial cells, except goblet cells. NPR1 was also expressed in inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, whereas NPR1 immunodetection was faint in underlying smooth muscle cells. Although we cannot exclude a role of inflammatory cells based on the present results, the removal of the bronchial epithelium completely abolished the bronchial relaxant effects of BNP, suggesting a BNP-related, post-transductional, control of bronchial contractility involving bronchial epithelium. Our results differ from those reported in previous papers (Labat et al., 1988; Candenas et al., 1991; Fernandes et al., 1992), which suggested that there are no NPRs in human ASM. This discrepancy can be explained from differences in experimental protocols as well as in natriuretic peptides employed in the various studies. Also Fernandes et al., 1992 suggested that the weak bronchodilatation observed in response to natriuretic peptides was not due to a direct relaxant effect on ASM cells, in contrast with the reported role of NPRs in cultured human ASM cells based on the concentration-dependent increase in cGMP levels (Hamad et al., 1997). We were able to show the presence of NPR1 in epithelial and in inflammatory cells of human isolated and control bronchial tissue, whereas these receptors were only barely detectable in ASM cells. Moreover, the relaxant effect of BNP was completely abolished by removal of the epithelium. The functional antagonistic effects of BNP were more pronounced in non-sensitized bronchi contracted by carbachol and in passively sensitized bronchi contracted by histamine. This discrepancy, and the hyper-responsiveness of sensitized bronchi to the histaminergic but not to the cholinergic tone, may be explained because the contractile effect of histamine is indirect, as has been suggested elsewhere (Schmidt and Rabe, 2000), and the passive sensitization is working at this indirect level, for example, influencing sensory nerves (Rabe, 1998; Schmidt et al., 2000). Interestingly, NPR1 expression was unchanged by sensitization, but increased in BNP-treated bronchi after carbachol or histamine treatment compared to control. Expression of NPR1 was increased significantly by cholinergic or histaminergic stimulation, in both sensitized and non-sensitized tissues, a phenomenon already reported in cardiac myocytes in which α1-adrenoceptor agonists and carbachol induced atrial natriuretic factor expression (Ramirez et al., 1995; 1997;). Some reports indicate that ASM itself may orchestrate and regulate the function of other structural cells that affect airway inflammation and bronchoconstriction (Panettieri et al., 2008; Damera et al., 2009) Although further studies are needed to clarify the BNP-related downstream mechanism(s) that involve cooperation between human bronchial epithelium and ASM and the role of smooth muscle cells in NO release, some initial considerations can be made. Our results with BNP-treated bronchial epithelial cells are in line with previous reports showing that BNP binding elicits the vesicular release of acetylcholine from bronchial epithelial cells, including neuroendocrine and brush cells (Wessler et al., 2003; Kummer et al., 2008). Although there is less acetylcholine released from the airway epithelium compared to that from neurons (Kummer et al., 2008; Wessler and Kirkpatrick, 2008), it seems to be sufficient to activate postsynaptic M2 muscarinic receptors on the surface of ASM cells (Kummer et al., 2008), which in turn increase NO and cGMP production, at least in rat atria (Sterin-Borda et al., 1995). Moreover, treatment with low concentrations of acetylcholine in epithelium-denuded bronchi increased NO release. Intriguingly, NO-mediated bronchorelaxation, secondary to M2 muscarinic receptor activation, is more marked at lower than higher acetylcholine concentrations (Sterin-Borda et al., 1995; Range et al., 1997; Ganzinelli et al., 2007). In any case, in the present study, the maximal BNP-dependent relaxant activity also increased in iNOS transcripts, confirming that NO synthesis plays a role in the downstream mechanisms of BNP-dependent control of bronchial tone (Hamad et al., 1997; Range et al., 1997). In order to test the hypothesis that the postulated NPR1 activation in human airways elicited the release of epithelial acetylcholine and downstream activation of smooth muscle M2 receptors and NO release, we used three experimental approaches: (i) pretreatment with methoctramine, an M2 muscarinic receptor antagonist, at a concentration that did not bind to other muscarinic receptor subtypes (Wess et al., 1988; Delmendo et al., 1989; Aas and Maclagan, 1990; Gosens et al., 2006); (ii) pretreatment with the NOS inhibitor, L-NAME; and (iii) pretreatment with the inhibitor of iNOS, aminoguanidine. It has been reported that, although aminoguanidine also partially blocks eNOS (the selectivity for iNOS vs. eNOS is 10-fold greater), the concentration (100 µM) employed in our experiments to inhibit iNOS would cause only negligible inhibition of eNOS (Alderton et al., 2001). Since methoctramine, L-NAME and aminoguanidine abolished BNP effects in both non-sensitized and passively sensitized bronchi, it is likely that NPR1 activation in human airways elicited the downstream activation of M2 smooth muscle receptors and subsequent NO release. The influence of the intramural release of acetylcholine in the downstream mechanisms of BNP-dependent bronchial tone regulation was confirmed by blocking the relaxant effect of BNP with quinine, an inhibitor of the release of endogenous acetylcholine (Arndt et al., 2001; Wessler et al., 2001; Lips et al., 2005; Schlereth et al., 2006).

Our findings suggest that the bronchial relaxation induced by BNP may be associated with the activation of NPR1 localized on the bronchial epithelium. We evaluated the levels of mRNA for the BNP receptor (NPR1) because available NRP inhibitors also antagonize NRP2 activity (D'Souza et al., 2004). Of course, the expression of a receptor subtype by PCR is not always correlated with functional involvement of the subtype, as in the case of muscarinic receptors, of which the M2 subtype is dominant in ASM, whereas the minor M3 receptor fraction is primarily responsible for contraction (Fryer and Jacoby, 1998). However, our evidence of BNP-dependent increase of NPR1 mRNA is in accordance with the evidence that BNP induces smooth muscle relaxation primarily through the activation of NPR1 (Ahluwalia et al., 2004; D'Souza et al., 2004). In addition, our results also suggest that the maximal BNP-dependent relaxant activity was coupled to the increase of iNOS transcript levels in non-epithelial bronchial tissue, because iNOS mRNA did not increase in epithelium-denuded isolated bronchi and NO release was unchanged in BNP-stimulated airway bronchial epithelial cells in vitro.

Stimulation by BNP of isolated bronchi and bronchial epithelial cells in vitro induced the release of acetylcholine at low concentration. In this light, our results are in accordance with those previously reported by Moffat et al. (Moffatt et al., 2004), which indicated that epithelium removal attenuated acetylcholine release from mouse airway epithelium. We also have clarified that BNP induced release of low levels of acetylcholine from human bronchial epithelial cells, and that low concentrations (pM-nM) of acetylcholine induced relaxation of human isolated bronchi. Paradoxically, in human isolated bronchi, acetylcholine at low concentrations induced bronchial relaxation, in contrast to results reported in the mouse model (Moffatt et al., 2004). The bronchial relaxation mediated by BNP is likely to be mediated by increased NO release in underlying, non-epithelial, bronchial tissues, including smooth muscle cells.

In conclusion, our results provided strong evidence that the epithelial cells mediate the BNP-induced relaxant activity in human isolated bronchi. It is likely that bronchial epithelial cells regulate the BNP-induced relaxant activity in human isolated bronchi by an autocrine loop, involving BNP-induced low-levels of acetylcholine release from airway epithelium (Klapproth et al., 1997; Proskocil et al., 2004), that stimulates NO release from underlying non-epithelial bronchial tissues. This suggests a teleological role for elevated BNP concentrations, at least in COPD patients, in whom BNP might be part of a response aimed at mitigating the effects of the disease. These findings add an important piece of information to the local reciprocal interactions of BNP with bronchial tone control and suggest alternative pharmacological options for therapy of chronic airway disease, including bronchial asthma or COPD.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Italian Association for Cancer Research that partially supported A. O.'s research.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ASM

airway smooth muscle

- BNP

brain natriuretic peptide

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- E

effect

- Emax

maximal response

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- KH

Krebs–Henseleit buffer solution

- L-NAME

Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride

- MTT

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- NPR

natriuretic peptide receptor

- pGC

particulate guanylate cyclase

- Ki

receptor binding affinity

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity with interests in the subject of this manuscript.

Supporting Information

Teaching Materials; Figs 1–7 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- Aas P, Maclagan J. Evidence for prejunctional M2 muscarinic receptors in pulmonary cholinergic nerves in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;101:73–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia A, MacAllister RJ, Hobbs AJ. Vascular actions of natriuretic peptides. Cyclic GMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Basic Res Cardiol. 2004;99:83–89. doi: 10.1007/s00395-004-0459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman MJ, Yaegashi M, Khiangte Z, Murugan AT, Abe O, Marmur JD. Bronchodilator effect of infused B-type natriuretic peptide in asthma. Chest. 2006;130:66–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: structure, function and inhibition. Biochem J. 2001;357(Pt 3):593–615. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl. 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt P, Volk C, Gorboulev V, Budiman T, Popp C, Ulzheimer-Teuber I, et al. Interaction of cations, anions, and weak base quinine with rat renal cation transporter rOCT2 compared with rOCT1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F454–F468. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.3.F454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi C, Gutkowska J, Thibault G, Garcia R, Genest J, Cantin M. Radioautographic localization of 125I-atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) in rat tissues. Histochemistry. 1985;82:441–452. doi: 10.1007/BF02450479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candenas ML, Naline E, Puybasset L, Devillier P, Advenier C. Effect of atrial natriuretic peptide and on atriopeptins on the human isolated bronchus. Comparison with the reactivity of the guinea-pig isolated trachea. Pulm Pharmacol. 1991;4:120–125. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(91)90062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza SP, Davis M, Baxter GF. Autocrine and paracrine actions of natriuretic peptides in the heart. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;101:113–129. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damera G, Tliba O, Panettieri RA., Jr Airway smooth muscle as an immunomodulatory cell. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009;22:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmendo RE, Michel AD, Whiting RL. Affinity of muscarinic receptor antagonists for three putative muscarinic receptor binding sites. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;96:457–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devillier P, Corompt E, Breant D, Caron F, Bessard G. Relaxation and modulation of cyclic AMP production in response to atrial natriuretic peptides in guinea pig tracheal smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;430:325–333. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes LB, Preuss JM, Goldie RG. Epithelial modulation of the relaxant activity of atriopeptides in rat and guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;212:187–194. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freas W, Hart JL, Golightly D, McClure H, Muldoon SM. Contractile properties of isolated vascular smooth muscle after photoradiation. Am J Physiol. 1989;256(3 Pt 2):H655–H664. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.3.H655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Muscarinic receptors and control of airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(5 Pt 3):S154–S160. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.supplement_2.13tac120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulcher ML, Gabriel S, Burns KA, Yankaskas JR, Randell SH. Well-differentiated human airway epithelial cell cultures. Methods Mol Med. 2005;107:183–206. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-861-7:183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzinelli S, Joensen L, Borda E, Bernabeo G, Sterin-Borda L. Mechanisms involved in the regulation of mRNA for M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and endothelial and neuronal NO synthases in rat atria. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:175–185. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemici G, Erdim R, Celiker A, Tokay S, Ones T, Inanir S, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide levels in patients with COPD and normal right ventricular function. Adv Ther. 2008;25:674–680. doi: 10.1007/s12325-008-0067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LS, Gilman A, Brunton LL. Goodman & Gilman's Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 11th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gosens R, Zaagsma J, Meurs H, Halayko AJ. Muscarinic receptor signaling in the pathophysiology of asthma and COPD. Respir Res. 2006;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamad AM, Range S, Holland E, Knox AJ. Regulation of cGMP by soluble and particulate guanylyl cyclases in cultured human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(4 Pt 1):L807–L813. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.4.L807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatake K, Wakabayashi I. Ethanol suppresses L-arginine-induced relaxation response of rat aorta stimulated with bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2000;35:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulks G, Jardine AG, Connell JM, Thomson NC. Effect of atrial natriuretic factor on bronchomotor tone in the normal human airway. Clin Sci (Lond) 1990;79:51–55. doi: 10.1042/cs0790051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y, Kawayama T, Iwanaga T, Aizawa H. High plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels in stable COPD without pulmonary hypertension or cor pulmonale. Intern Med. 2009;48:503–512. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K, Murad F. ANP relaxes bovine tracheal smooth muscle and increases cGMP. Am J Physiol. 1989;256(3 Pt 1):C495–C500. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.3.C495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Watanabe T, Watanabe M, Hasegawa S, Uchiyama Y. Effects of atrial natriuretic peptide on type II alveolar epithelial cells of the rat lung. Autoradiographic and morphometric studies. J Anat. 1989;166:85–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S, Uchida K, Ito T, Kozuka M, Shimonaka M, Mizuno T, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of atrial natriuretic peptide receptor in bovine kidney and lung. J Histochem Cytochem. 1989;37:1739–1742. doi: 10.1177/37.11.2553804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapproth H, Reinheimer T, Metzen J, Munch M, Bittinger F, Kirkpatrick CJ, et al. Non-neuronal acetylcholine, a signalling molecule synthezised by surface cells of rat and man. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;355:515–523. doi: 10.1007/pl00004977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer W, Lips KS, Pfeil U. The epithelial cholinergic system of the airways. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:219–234. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labat C, Norel X, Benveniste J, Brink C. Vasorelaxant effects of atrial peptide II on isolated human pulmonary muscle preparations. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;150:397–400. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips KS, Volk C, Schmitt BM, Pfeil U, Arndt P, Miska D, et al. Polyspecific cation transporters mediate luminal release of acetylcholine from bronchial epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:79–88. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0363OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matera MG, Calzetta L, Parascandolo V, Curradi G, Rogliani P, Cazzola M. Relaxant effect of brain natriuretic peptide in nonsensitized and passively sensitized isolated human bronchi. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009;22:478–482. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt JD, Cocks TM, Page CP. Role of the epithelium and acetylcholine in mediating the contraction to 5-hydroxytryptamine in the mouse isolated trachea. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:1159–1166. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed AA, Januzzi JL., Jr Natriuretic peptides in the diagnosis and management of acute heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2009;5:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky H. Intuitive Biostatistics. 1st edn. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky H, Christopoulos A. Fitting Models to Biological Data Using Linear and Nonlinear Regression : A Practical Guide to Curve Fitting. 1st edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mukoyama M, Nakao K, Hosoda K, Suga S, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, et al. Brain natriuretic peptide as a novel cardiac hormone in humans. Evidence for an exquisite dual natriuretic peptide system, atrial natriuretic peptide and brain natriuretic peptide. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1402–1412. doi: 10.1172/JCI115146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohbayashi H, Suito H, Takagi K. Compared effects of natriuretic peptides on ovalbumin-induced asthmatic model. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;346:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omland T, Hagve TA. Natriuretic peptides: physiologic and analytic considerations. Heart Fail Clin. 2009;5:471–487. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlandi A, Ferlosio A, Ciucci A, Francesconi A, Lifschitz-Mercer B, Gabbiani G, et al. Cellular retinol binding protein-1 expression in endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma: diagnostic and possible therapeutic implications. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:797–803. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlandi A, Francesconi A, Marcellini M, Di Lascio A, Spagnoli LG. Propionyl-L-carnitine reduces proliferation and potentiates Bax-related apoptosis of aortic intimal smooth muscle cells by modulating nuclear factor-kappaB activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4932–4942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panettieri RA, Jr, Kotlikoff MI, Gerthoffer WT, Hershenson MB, Woodruff PG, Hall IP, et al. Airway smooth muscle in bronchial tone, inflammation, and remodeling: basic knowledge to clinical relevance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:248–252. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1217PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisano C, Vesci L, Milazzo FM, Guglielmi MB, Fodera R, Barbarino M, et al. Metabolic approach to the enhancement of antitumor effect of chemotherapy: a key role of acetyl-L-carnitine. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3944–3953. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter LR, Abbey-Hosch S, Dickey DM. Natriuretic peptides, their receptors, and cyclic guanosine monophosphate-dependent signaling functions. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:47–72. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter LR, Yoder AR, Flora DR, Antos LK, Dickey DM. Natriuretic peptides: their structures, receptors, physiologic functions and therapeutic applications. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;191:341–366. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68964-5_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskocil BJ, Sekhon HS, Jia Y, Savchenko V, Blakely RD, Lindstrom J, et al. Acetylcholine is an autocrine or paracrine hormone synthesized and secreted by airway bronchial epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2498–2506. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe KF. Mechanisms of immune sensitization of human bronchus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(5 Pt 3):S161–S170. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.supplement_2.13tac130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez MT, Post GR, Sulakhe PV, Brown JH. M1 muscarinic receptors heterologously expressed in cardiac myocytes mediate Ras-dependent changes in gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8446–8451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez MT, Sah VP, Zhao XL, Hunter JJ, Chien KR, Brown JH. The MEKK-JNK pathway is stimulated by alpha1-adrenergic receptor and ras activation and is associated with in vitro and in vivo cardiac hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14057–14061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Range SP, Holland ED, Basten GP, Knox AJ. Regulation of guanosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate in ovine tracheal epithelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1249–1254. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinheimer T, Bernedo P, Klapproth H, Oelert H, Zeiske B, Racke K, et al. Acetylcholine in isolated airways of rat, guinea pig, and human: species differences in role of airway mucosa. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(5 Pt 1):L722–L728. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.5.L722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinheimer T, Baumgartner D, Hohle KD, Racke K, Wessler I. Acetylcholine via muscarinic receptors inhibits histamine release from human isolated bronchi. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156(2 Pt 1):389–395. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.96-12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Sekizawa K, Yamaya M. Bronchial hyperreactivity in the peripheral airways. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1995;175:143–162. doi: 10.1620/tjem.175.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlereth T, Birklein F, an Haack K, Schiffmann S, Kilbinger H, Kirkpatrick CJ, et al. In vivo release of non-neuronal acetylcholine from the human skin as measured by dermal microdialysis: effect of botulinum toxin. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:183–187. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D, Rabe KF. Immune mechanisms of smooth muscle hyperreactivity in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:673–682. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.105705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D, Watson N, Ruehlmann E, Magnussen H, Rabe KF. Serum immunoglobulin E levels predict human airway reactivity in vitro. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:233–241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterin-Borda L, Echague AV, Leiros CP, Genaro A, Borda E. Endogenous nitric oxide signalling system and the cardiac muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-inotropic response. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:1525–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolz D, Breidthardt T, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, Miedinger D, Leuppi J, et al. Use of B-type natriuretic peptide in the risk stratification of acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2008;133:1088–1094. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi K, Araki N, Suzuki K. Relaxant effect of C-type natriuretic peptide on guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle. Arzneimittelforschung. 1992;42:1329–1331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki J, Tagaya E, Sakai A, Konno K. Effects of macrolide antibiotics on neurally mediated contraction of human isolated bronchus. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:853–859. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson N, Bodtke K, Coleman RA, Dent G, Morton BE, Ruhlmann E, et al. Role of IgE in hyperresponsiveness induced by passive sensitization of human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:839–844. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9117014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J, Angeli P, Melchiorre C, Moser U, Mutschler E, Lambrecht G. Methoctramine selectively blocks cardiac muscarinic M2 receptors in vivo. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1988;338:246–249. doi: 10.1007/BF00173395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessler I, Kirkpatrick CJ. Acetylcholine beyond neurons: the non-neuronal cholinergic system in humans. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1558–1571. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessler I, Roth E, Deutsch C, Brockerhoff P, Bittinger F, Kirkpatrick CJ, et al. Release of non-neuronal acetylcholine from the isolated human placenta is mediated by organic cation transporters. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:951–956. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessler I, Kilbinger H, Bittinger F, Unger R, Kirkpatrick CJ. The non-neuronal cholinergic system in humans: expression, function and pathophysiology. Life Sci. 2003;72:2055–2061. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.