The MAP kinase Slt2 is required for both mitophagy and pexophagy, whereas the MAP kinase Hog1 acts specifically in mitophagy.

Abstract

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to simply as autophagy) is a catabolic pathway that mediates the degradation of long-lived proteins and organelles in eukaryotic cells. The regulation of mitochondrial degradation through autophagy plays an essential role in the maintenance and quality control of this organelle. Compared with our understanding of the essential function of mitochondria in many aspects of cellular metabolism such as energy production and of the role of dysfunctional mitochondria in cell death, little is known regarding their degradation and especially how upstream signaling pathways control this process. Here, we report that two mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), Slt2 and Hog1, are required for mitophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Slt2 is required for the degradation of both mitochondria and peroxisomes (via pexophagy), whereas Hog1 functions specifically in mitophagy. Slt2 also affects the recruitment of mitochondria to the phagophore assembly site (PAS), a critical step in the packaging of cargo for selective degradation.

Introduction

Autophagy functions as a highly conserved degradative mechanism in eukaryotic cells. During autophagy, cytosolic components and organelles are sequestered into autophagosomes, double-membrane vesicles, and then delivered to the lysosome in mammalian cells or the vacuole in yeast for degradation (Xie and Klionsky, 2007). This process has attracted increasing attention in recent years because it is involved in various aspects of cell physiology, including survival during nitrogen starvation, clearance of excess or dysfunctional proteins and organelles, proper development, and aging (Mizushima et al., 2008).

During nitrogen starvation, autophagy is generally considered to be nonselective. The unique mechanism by which the initial sequestering compartment, the phagophore, expands into an autophagosome allows for an extremely flexible capacity for cargo. In addition to this nonselective or bulk autophagy, selective types of autophagy are used for biosynthetic transport (the cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting [Cvt] pathway), and to recognize and degrade specific cargoes or organelles. These latter include the selective degradation of mitochondria (mitophagy), peroxisomes (pexophagy), and ribosomes (ribophagy; Reggiori et al., 2005; Kanki and Klionsky, 2008; Kraft et al., 2008; Geng et al., 2010). Among different kinds of selective autophagy, mitophagy is particularly crucial because of the significance of mitochondria in cellular homeostasis. In particular, mitochondria supply energy to the cell for a variety of cellular activities. However, mitochondria are also the major source of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause oxidative damage to cellular components including DNA, proteins, and lipids (Wallace, 2005). Accumulation of damaged mitochondria and the concomitant increase in ROS is related to aging, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases (Yen and Klionsky, 2008). Therefore, quality control and clearance of damaged or excess mitochondria through autophagy is an important cellular activity.

Until now, four primary signaling pathways have been characterized as playing a role in the negative regulation of nonselective autophagy. The regulatory kinases of these pathways are the target of rapamycin (TOR), Sch9, Ras/cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), and Pho85, the latter of which also plays a positive role in regulation (Budovskaya et al., 2004; Yorimitsu et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2010). In the case of TOR and PKA, the corresponding signaling events negatively regulate the activity of Atg1 and Atg13 and inhibit the induction of autophagy, whereas Pho85 acts in conjunction with various cyclins to inhibit Gcn2 and Pho4 to exert a negative effect, and inhibits Sic1 for positive regulation. In contrast to the signaling pathways upstream of bulk autophagy, which have been studied to some extent, the regulatory mechanisms of mitophagy remain largely unexplored.

In this report, we analyzed the functions of two MAPKs, Slt2 and Hog1, in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and showed that both are required for mitophagy. Slt2 is a MAPK involved in the protein kinase C (Pkc1) cell wall integrity kinase signaling pathway, and responds to cell wall stress (Levin, 2005). Here, we show that Slt2 is required for pexophagy and mitophagy, but not the Cvt pathway or bulk autophagy. Hog1 is a MAPK homologue of mammalian p38, and responds to hyper-osmotic stress (Westfall et al., 2004). Different from p38, which is a negative regulator of autophagy, Hog1 is a positive regulator only required for mitophagy, but not other types of selective autophagy or bulk autophagy. We thus propose that these two MAPK pathways play a critical role in organelle quality control.

Results

The MAPK Slt2 and upstream signaling components are involved in mitophagy

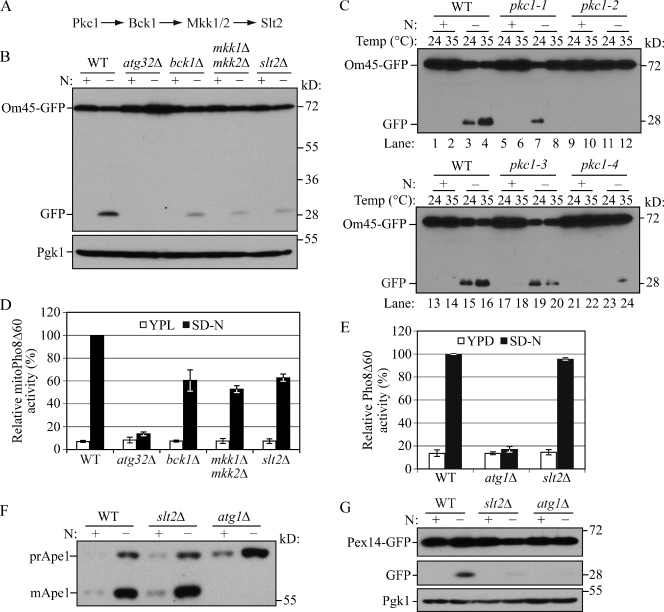

In a recent genome-wide yeast mutant screen for mitophagy-defective strains we found that BCK1, a gene encoding a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK), is required for mitophagy (Kanki et al., 2009a). Bck1 is involved in the cell wall integrity signaling pathway, which includes Pkc1, Bck1, redundant Mkk1/2, and Slt2 kinases (Levin, 2005). Upon cell wall stress, Bck1 is activated by Pkc1 and then phosphorylates and activates Mkk1/2, which in turn transmits the signal to Slt2 (Fig. 1 A; Heinisch et al., 1999). We asked whether all of the components of this signaling pathway are involved in mitophagy. To detect mitophagy, we first used the Om45-GFP processing assay. OM45 encodes a mitochondrial outer membrane protein, and a chromosomally tagged version with the GFP at the C terminus is correctly localized on this organelle. When mitophagy is induced, mitochondria, along with Om45-GFP, are delivered into the vacuole for degradation. Om45 is proteolytically removed or degraded, whereas the GFP moiety is relatively stable and accumulates in the vacuole. Thus, mitophagy can be monitored based on the appearance of free GFP by immunoblot (Kanki and Klionsky, 2008).

Figure 1.

Slt2 is involved in mitophagy and pexophagy, but not bulk autophagy or the Cvt pathway. (A) The Slt2 MAPK pathway. (B) Om45-GFP processing is blocked in bck1Δ, mkk1/2Δ, and slt2Δ mutants. OM45 was chromosomally tagged with GFP in the wild-type (TKYM22), atg32Δ (TKYM130), bck1Δ (KWY51), mkk1Δ mkk2Δ (KDM1303), and slt2Δ (KDM1305) strains. Cells were cultured in YPL to mid-log phase, then shifted to SD-N and incubated for 6 h. Samples were taken before (+) and after (−) starvation. Immunoblotting was done with anti-YFP antibody and the positions of full-length Om45-GFP and free GFP are indicated. Anti-Pgk1 was used as a loading control. (C) Om45-GFP processing is blocked in pkc1 mutants. Om45-GFP processing was examined in wild-type (KDM2023), pkc1-1 (KDM2011), pkc1-2 (KDM2009), pkc1-3 (KDM2010), and pkc1-4 (KDM2012) strains. Cells were cultured in YPL at 24°C to mid-log phase. For each strain, the culture was then divided into two parts. Both were shifted to SD-N and one half was incubated for 6 h at 24°C while the other was shifted to 35°C. Protein extracts were probed with anti-YFP antibody. (D) MitoPho8Δ60 activity is reduced in Slt2 pathway mutants. Wild-type (KWY20), atg32Δ (KWY22), bck1Δ (KWY33), mkk1/2Δ (KDM1003), and slt2Δ (KDM1008) cells were cultured as in A. The mitoPho8Δ60 assay was performed as described in Materials and methods. Error bars, standard deviation (SD) were obtained from three independent repeats. (E) The Pho8Δ60 activity (nonspecific autophagy) is unaffected in the slt2Δ mutant. Wild-type (WLY176), atg1Δ (WLY192), and slt2Δ (KDM1401) cells were cultured as in A, but the time of incubation in SD-N was reduced to 2 h. The Pho8Δ60 assay was performed as described in Materials and methods. Error bars, SD were obtained from three independent repeats. (F) The Cvt pathway is unaffected in the slt2Δ mutant. Wild-type (SEY6210), atg1Δ (WHY001), and slt2Δ (KDM1213) cells were cultured in YPD to mid-log phase, then shifted to SD-N and incubated for 1 h. Samples were taken before and after nitrogen starvation. Immunoblotting was done with anti-Ape1 antibody and the positions of precursor Ape1 and mature Ape1 are indicated. (G) Pex14-GFP processing is blocked in the slt2Δ mutant. PEX14 was chromosomally tagged with GFP in wild-type (TKYM67), atg1Δ (TKYM72), and slt2Δ (KDM1101) strains. Cells were grown in oleic acid–containing medium for 19 h and shifted to SD-N for 4 h. Samples were taken before and after nitrogen starvation. Immunoblotting was done with anti-YFP antibody and the positions of full-length Pex14-GFP and free GFP are indicated. Anti-Pgk1 was used as a loading control.

Atg32 is a mitophagy-specific receptor and is necessary for the recruitment of mitochondria to the PAS through interaction with Atg11, which is an adaptor protein for selective types of autophagy (Kanki et al., 2009b; Okamoto et al., 2009). After 6 h of nitrogen starvation in the presence of glucose, free GFP was detected in wild-type but not atg32Δ cells (Fig. 1 B). Mitophagy was severely blocked in bck1Δ and slt2Δ cells. Even though the amount of free GFP derived from Om45-GFP in mkk1Δ or mkk2Δ single-mutant cells appeared essentially identical to the wild type (not depicted), an mkk1Δ mkk2Δ double-deletion mutant showed a strong defect in mitophagy (Fig. 1 B). Mitophagy activities of pkc1 temperature-sensitive mutants were also measured at both permissive and restrictive temperatures. In the wild-type strain, Om45-GFP was processed at both temperatures with a greater level of free GFP detected at 35°C than at 24°C (Fig. 1 C, lanes 3 and 4, and lanes 15 and 16). In contrast, in the pkc1-1, pkc1-2, pkc1-3, and pkc1-4 mutants, Om45-GFP processing was substantially reduced relative to the wild type at the nonpermissive temperature (Fig. 1 C, compare lane 4 to lanes 8 and 12, and lane 16 to lanes 20 and 24), suggesting that the Pkc1–Bck1–Mkk1/2–Slt2 signaling pathway is required for mitophagy.

To extend our analysis and precisely quantify mitophagy, we took advantage of the mitoPho8Δ60 assay to examine the extent of mitophagy defects in these mutants. PHO8 encodes a vacuolar alkaline phosphatase, and its delivery into the vacuole is dependent on the ALP pathway (Klionsky and Emr, 1989). Pho8Δ60, the truncated form of Pho8 with 60 N-terminal amino acid residues including its transmembrane domain deleted, is unable to enter the endoplasmic reticulum, remains in the cytosol, and is delivered into the vacuole only through bulk autophagy (Noda et al., 1995). In this way, the magnitude of bulk autophagy is quantified by measuring the activity of alkaline phosphatase in nitrogen starvation conditions. If PHO8Δ60 is fused with a mitochondrial targeting sequence, the encoded protein is specifically localized in mitochondria, and the ensuing alkaline phosphatase activity becomes an indicator of mitophagy (Campbell and Thorsness, 1998). When mitophagy was induced, wild-type cells showed a dramatic increase in mitoPho8Δ60 activity, whereas essentially no increase was detected in atg32Δ cells where mitophagy was completely blocked (Fig. 1 D). In bck1Δ, mkk1/2Δ, and slt2Δ cells, a severe decrease of mitoPho8Δ60 activity was seen compared with wild-type cells; these mutants displayed ∼60, 53, and 62% of the mitophagy activity of the wild type, respectively. These results suggested that Bck1, Mkk1/2, and Slt2 regulate mitophagy through a linear signal transduction pathway.

Slt2 is required for pexophagy, but not the Cvt pathway or bulk autophagy

Considering the apparent role of Slt2 in mitophagy, we next asked whether this kinase is also involved in bulk autophagy or other types of selective autophagy. Bulk autophagy was tested by the Pho8Δ60 assay. Atg1 is a cytosolic protein kinase required for vesicle formation, and autophagic flux is absent in atg1Δ cells (Abeliovich et al., 2003; Cheong et al., 2008). When bulk autophagy was induced in nitrogen starvation conditions, the Pho8Δ60-dependent alkaline phosphatase activity showed a strong increase in wild-type and slt2Δ cells, but remained at a basal level (i.e., the level before nitrogen starvation) in atg1Δ cells (Fig. 1 E).

Although the Cvt pathway is biosynthetic, it represents a selective type of autophagy and shares many of the same molecular components with bulk autophagy. The precursor form of aminopeptidase I (prApe1) is delivered to the vacuole via the Cvt pathway in rich conditions and through autophagy in nitrogen starvation conditions (Baba et al., 1997). After entering the vacuole, the N-terminal propeptide of prApe1 is cleaved to generate the mature form (mApe1) and the resulting difference in molecular mass can be differentiated by Western blot (Klionsky et al., 1992). The maturation of prApe1 appeared normal in slt2Δ cells compared with wild-type cells in both growing and nitrogen starvation conditions, whereas atg1Δ cells displayed the expected block and accumulated only prApe1 (Fig. 1 F).

As indicated above, the Cvt pathway is unusual in that it is a biosynthetic autophagy-related pathway. Therefore, we decided to examine another type of specific organelle degradation, pexophagy. PEX14 encodes a peroxisome integral membrane protein. After chromosomal tagging with GFP, the encoded protein, Pex14-GFP, is localized on the peroxisome and becomes a marker for pexophagy, similar to Om45-GFP for mitophagy; when pexophagy is induced, Pex14-GFP is delivered into the vacuole and pexophagy is detected by the release of free GFP (Reggiori et al., 2005). Pex14-GFP was processed after 4 h of pexophagy induction in wild-type cells, but this processing was almost completely blocked in slt2Δ cells similar to the atg1Δ negative control (Fig. 1 G). These results indicated that Slt2 is involved in both mitophagy and pexophagy, but not the Cvt pathway or bulk autophagy.

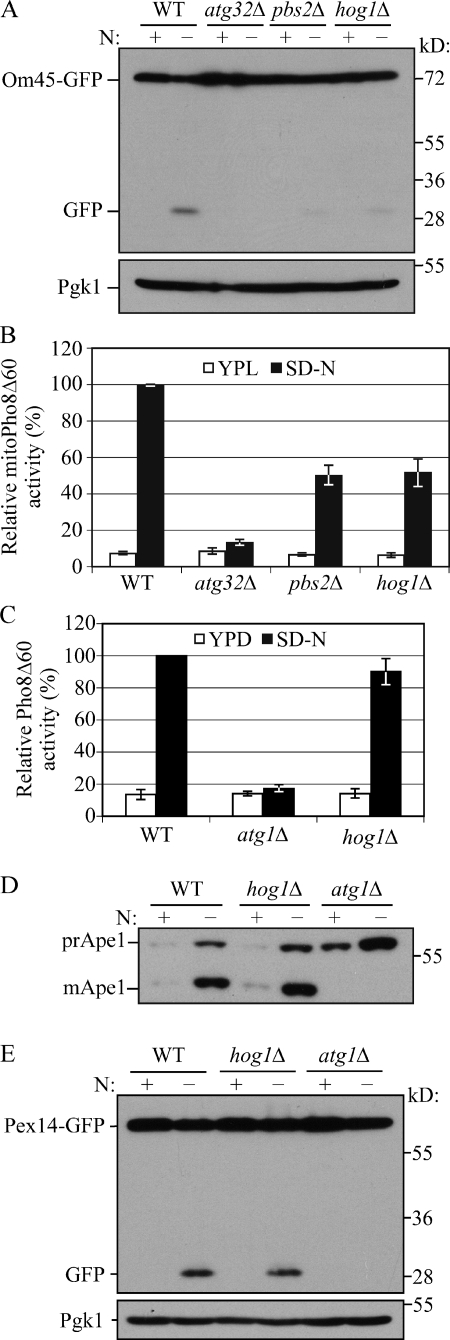

The MAPK Hog1 and upstream kinase Pbs2 are mitophagy-specific regulators

Five MAPK-signaling pathways exist in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and these MAPKs are involved in stress response and filamentous growth. Among these MAPKs, Hog1 responds to osmotic stress and regulates cellular metabolism. In Candida albicans, Hog1 controls respiratory metabolism and mitochondrial function (Alonso-Monge et al., 2009). Because of the role of the Slt2 MAPK pathway in selective organelle degradation, we were also interested in the potential role of Hog1 in mitophagy. In the Hog1 signaling pathway, Pbs2 is the MAPKK upstream of Hog1, and the activation of Hog1 is dependent on its phosphorylation by Pbs2 (Brewster et al., 1993). We again used the Om45-GFP processing assay to test mitophagy in both hog1Δ and pbs2Δ cells and found that there was minimal Om45-GFP processing relative to the wild-type positive control, similar to the atg32Δ negative control, which suggested a defect in mitophagy (Fig. 2 A). Furthermore, quantification by the mitoPho8Δ60 assay showed ∼50 and 52% of mitophagy activity in pbs2Δ and hog1Δ cells, respectively (Fig. 2 B). These results suggested that similar to Slt2, the Hog1 signaling pathway is also required for mitophagy.

Figure 2.

Hog1 is involved in mitophagy, but not other types of autophagy. (A) Om45-GFP processing is blocked in pbs2Δ and hog1Δ mutants. Om45-GFP processing was tested in wild-type (TKYM22), atg32Δ (TKYM130), pbs2Δ (KDM1309), and hog1Δ (KDM1307) cells with the methods described in Fig. 1 B. (B) MitoPho8Δ60 activity is reduced in hog1Δ and pbs2Δ mutants. The mitoPho8Δ60 activity was examined in wild-type (KWY20), atg32Δ (KWY22), pbs2Δ (KDM1005), and hog1Δ (KDM1015) cells as in Fig. 1 D. Error bars, SD were obtained from three independent repeats. (C) The Pho8Δ60 activity is unaffected in the hog1Δ mutant. The Pho8Δ60 assay was performed in wild-type (WLY176), atg1Δ (WLY192), and hog1Δ (KDM1403) cells as in Fig. 1 E. Error bars, SD were obtained from three independent repeats. (D) The Cvt pathway is unaffected in the hog1Δ mutant. Maturation of prApe1 was examined in wild-type (SEY6210), hog1Δ (KDM1214), and atg1Δ (WHY001) cells as in Fig. 1 F. (E) Pex14-GFP processing is unaffected in the hog1Δ mutant. Pex14-GFP processing was examined in wild-type (TKYM67), hog1Δ (KDM1102), and atg1Δ (TKYM72) cells as in Fig. 1 G.

As with Slt2, we extended our analysis by checking bulk autophagy, the Cvt pathway, and pexophagy. Our results showed that Pho8Δ60 activity (bulk autophagy), prApe1 maturation (the Cvt pathway), and Pex14-GFP processing (pexophagy) were all unaffected in hog1Δ cells compared with wild-type and atg1Δ cells (Fig. 2, C–E). These results suggested that, different from Slt2, the Pbs2 and Hog1 kinases are mitophagy-specific regulators.

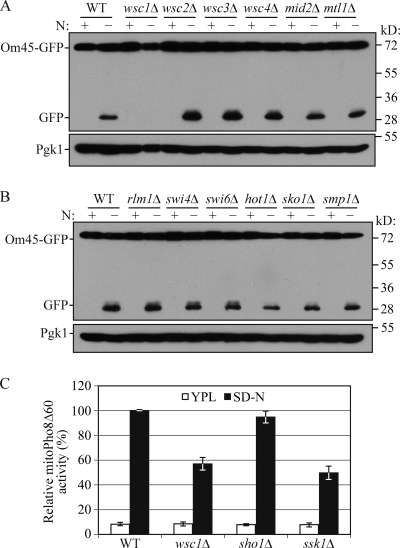

Wsc1 and Sln1 function as upstream sensors for input into the Slt2 and Hog1 signaling pathways

To obtain more information for the extension of these two signaling pathways, we began to search for upstream and downstream components of the Slt2 and Hog1 pathways. For the Slt2 signaling pathway, six cell surface sensors, Wsc1, Wsc2, Wsc3, Wsc4, Mid2, and Mtl1, and three transcriptional factors, Rlm1, Swi4, and Swi6, function as upstream sensors and downstream effectors, respectively. Based on the Om45-GFP processing assay, mitophagy was blocked in the wsc1Δ strain, but not in any of the other mutants (Fig. 3, A and B). The involvement of Wsc1 in mitophagy was confirmed with the mitoPho8Δ60 assay (Fig. 3 C).

Figure 3.

Wsc1 and Ssk1 are required for mitophagy. (A) Om45-GFP processing is blocked in wsc1Δ cells but not other mutants lacking cell surface sensors. Om45-GFP processing was tested in wild-type (KDM2023), wsc1Δ (KDM2024), wsc2Δ (KDM2025), wsc3Δ (KDM2026), wsc4Δ (KDM2027), mid2Δ (KDM2028), and mtl1Δ (KDM2029) cells as in Fig. 1 B. Protein extracts were probed with anti-YFP antibodies and anti-Pgk1 as a loading control. (B) Om45-GFP processing remains normal in rlm1Δ (KDM2030), swi4Δ (KDM2031), swi6Δ (KDM2032), sko1Δ (KDM2033), hot1Δ (KDM2035), and smp1Δ (KDM2034) mutants. Protein extracts were probed as in A. (C) The mitoPho8Δ60 activity is reduced in wsc1Δ (KDM1023) and ssk1Δ (KDM1021) mutants but not in the sho1Δ (KDM1022) mutant. Error bars, SD were obtained from three independent repeats.

In the Hog1 signaling pathway, Sho1 and Sln1 function as sensors in the plasma membrane that function in parallel pathways (Saito and Tatebayashi, 2004). Mitophagy was unaffected in a sho1Δ strain (Fig. 3 C), but was partially blocked in a conditional sln1 temperature-sensitive mutant at the nonpermissive temperature (Fig. S1 A). Sln1 is a negative regulator of the Hog1 pathway (Fig. S1 B); however, constitutively active Hog1 (e.g., due to defective Sln1) has a negative phenotype (Saito and Tatebayashi, 2004). Thus, a block in mitophagy in the sln1 mutant is in agreement with our data showing a defect in the hog1Δ strain (Fig. 2). Sln1 and its effector Ypd1 inhibit the Ssk1 kinase, an activator of Hog1. To extend our analysis of the upstream components, we examined an ssk1Δ strain. The ssk1Δ mutant displayed a partial block in mitoPho8Δ60 activity similar to the wsc1Δ mutant (Fig. 3 C). There are three known transcriptional factors, Sko1, Hot1, and Smp1, that function downstream of Hog1. Mitophagy was unaffected in sko1Δ, hot1Δ, and smp1Δ cells (Fig. 3 B). These results indicate that the upstream sensors and effectors in the Slt2 and Hog1 signaling pathways that involve the Wsc1 and Sln1 sensors, respectively, regulate mitophagy. However, the known transcriptional factors downstream of Slt2 and Hog1 that we tested had no apparent role in mitophagy.

Slt2 and Hog1 are also involved in post-log phase mitophagy

Mitophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae can be induced in two different conditions: nitrogen starvation and culturing cells to the post-log phase in a nonfermentable carbon source medium (Kanki et al., 2009a). Atg32 is required for both types of mitophagy; however, Atg33 is specifically involved in post-log phase mitophagy, which suggests that mitophagy is induced through different mechanisms depending on the conditions. We asked whether Slt2 and Hog1 are also required for post-log phase mitophagy. Wild-type, atg32Δ, slt2Δ, hog1Δ, and hog1Δ slt2Δ cells were cultured in lactate medium to log phase, and then grown for another 12, 24, and 36 h. The mitoPho8Δ60 activities of the slt2Δ, hog1Δ, and hog1Δ slt2Δ mutants were significantly reduced compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 4 A). These results indicated these two MAPK signaling pathways regulate both types of mitophagy.

Figure 4.

Mitophagy in post-log phase requires Slt2 and Hog1 signaling. (A) MitoPho8Δ60 activity is reduced in slt2Δ, hog1Δ, and hog1Δ slt2Δ mutants in post-log phase mitophagy. Wild-type (KWY20), atg32Δ (KWY22), slt2Δ (KDM1008), hog1Δ (KDM1015), and hog1Δ slt2Δ (KDM1025) cells were cultured in lactate medium to log phase and the cells were grown for another 12, 24, and 36 h. Samples were collected at each time point. The mitoPho8Δ60 assay was performed as described in Materials and methods. Error bars, SD were obtained from three independent repeats. (B) MitoPho8Δ60 activity is reduced in the hog1Δ slt2Δ double mutant in nitrogen starvation–induced mitophagy conditions. The mitoPho8Δ60 assay was performed in wild-type (KWY20), atg32Δ (KWY22), and hog1Δ slt2Δ (KDM1025) cells as in Fig. 1 E.

Finally, we examined the effect of combining the hog1Δ and slt2Δ mutations. Mitophagy was almost completely blocked in hog1Δ slt2Δ double-mutant cells; the mitoPho8Δ60 activity of the hog1Δ slt2Δ mutant was comparable to that of atg32Δ cells (Fig. 4 A). This phenotype could also be detected when mitophagy was induced by nitrogen starvation (Fig. 4 B). This result suggested that the strong defect of mitophagy in the hog1Δ slt2Δ mutant reflects an additive effect because these kinases regulate different steps of mitophagy in parallel pathways.

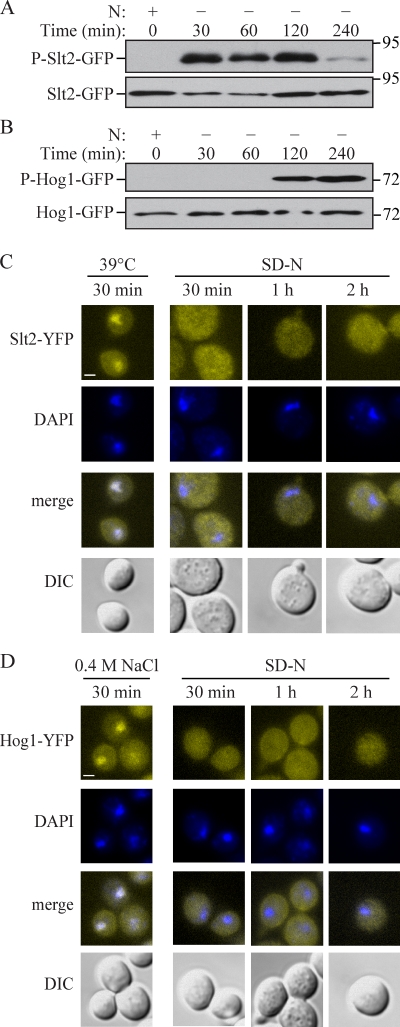

Slt2 and Hog1 are phosphorylated and remain in the cytosol during mitophagy

To investigate the response patterns of Slt2 and Hog1 during mitophagy, we examined the phosphorylation states of these proteins, which corresponds with their activation (Hahn and Thiele, 2002; Bicknell et al., 2010). When cells were grown on lactate medium, both Slt2 and Hog1 were nonphosphorylated and inactive, but became phosphorylated upon nitrogen starvation (Fig. 5, A and B). Phosphorylation of Slt2 was initiated at 30 min after cells were shifted to SD-N and was subsequently reduced at 4 h (Fig. 5 A); in contrast, Hog1 was activated at 2 h and retained its phosphorylated state at 4 h (Fig. 5 B). This result indicated that Slt2 responds quickly to mitophagy-inducing signals and might function in an early stage of mitophagy, and that Hog1 responds late and might function in a correspondingly later stage of the process.

Figure 5.

Hog1 and Slt2 are activated and remain in the cytosol during mitophagy. (A and B) SLT2 or HOG1 were chromosomally tagged with GFP. SLT2-GFP (KDM1218) or HOG1-GFP (KDM1217) cells were cultured in YPL to mid-log phase and shifted to SD-N for the indicated times. Samples were taken before (+) and at the indicated times after (−) nitrogen starvation. Immunoblotting was done with anti–phospho-Slt2 antibody in A, anti-phospho-Hog1 antibody in B, or anti-YFP antibody in both A and B. (C and D) Cells (SEY6210) transformed with plasmids encoding either Hog1-YFP or Slt2-YFP were cultured in SML to mid-log phase and shifted to SD-N for the indicated times, or cultured at 39°C for Slt2-YFP in C or treated with 0.4 M NaCl for Hog1-YFP in D. Samples were taken after each specific treatment, fixed, stained with DAPI to mark the nucleus, and observed by fluorescence microscopy. Representative pictures from single Z-section images are shown. DIC, differential interference contrast. Bars, 2.5 µm.

Although Slt2 and Hog1 can translocate to the nucleus and activate relevant transcription factors, depending on the stimulus, they also have cytoplasmic substrates. The observation that mitophagy was unaffected in rlm1Δ, swi4Δ, swi6Δ, sko1Δ, hot1Δ, and smp1Δ cells suggested that both Slt2 and Hog1 might control mitophagy through a mechanism other than transcriptional regulation. To monitor the distribution and localization of Slt2 and Hog1 during mitophagy, we fused both proteins with the venus variant of YFP and observed their localization during mitophagy-inducing conditions. It has been previously shown that during heat-shock stress (39°C) and hyper-osmotic stress (0.4 M NaCl), respectively, Hog1-YFP and Slt2-YFP translocate to the nucleus (Hahn and Thiele, 2002; Bicknell et al., 2010). Accordingly, we used these conditions to test and verify the functionality of our constructs. As expected, Slt2-YFP and Hog1-YFP showed clear nuclear localization under the respective stress conditions (Fig. 5, C and D). In contrast, during mitophagy Hog1-YFP and Slt2-YFP remained in the cytosol (Fig. 5, C and D). These results support the hypothesis that both Slt2 and Hog1 might activate some unknown cytoplasmic target to regulate mitophagy.

Atg32 recruitment to the PAS is perturbed in slt2Δ, but not hog1Δ mutants

The accumulation of the degrading portions of mitochondria at the PAS is a significant step during mitophagy (Kanki et al., 2009b). We first confirmed this event with the RFP-tagged mitochondria matrix protein Idh1 (Idh1-RFP) using GFP-Atg8 as the PAS marker. After 2 h of nitrogen starvation, a portion of mitochondria was located at the PAS (Fig. S2 A).

Atg32, which functions as an organelle-specific marker, is delivered into the vacuole together with mitochondria during mitophagy (Okamoto et al., 2009). In atg1Δ cells, when the autophagic flux is completely blocked, a portion of GFP-Atg32 accumulates at the PAS, which localizes to the periphery of the vacuole in nitrogen starvation conditions (Fig. S2 B; Kanki et al., 2009b). The PAS-localized Atg32 indicates the initiation of mitochondria-specific autophagosome (mitophagosome) formation. To further investigate how Slt2 and Hog1 regulate mitophagy, we focused on Atg32, which is the only known mitophagy receptor in yeast. We first examined the protein level of Atg32 in slt2Δ and hog1Δ mutants during mitophagy and found that the amount of the Atg32 protein was unaffected by either mutation (unpublished data). Thus, we ruled out transcriptional control for this mitochondria tag as being the explanation for the mitophagy defect.

As Slt2 and Hog1 are both involved in mitophagy, we asked whether Atg32 recruitment to the PAS was disturbed in the slt2Δ or hog1Δ mutant. In atg1Δ cells, GFP-Atg32 was present on mitochondria, but not at the PAS to an appreciable extent in vegetative conditions (SML medium). GFP-Atg32 accumulated at the PAS in ∼45% (2 h) or 77% (4 h) of the atg1Δ cells in nitrogen starvation conditions, whereas only 17% (2 h) or 37% (4 h) of the cells displayed PAS-localized GFP-Atg32 in atg1Δ slt2Δ mutants (Fig. 6). Although mitophagy was severely blocked in hog1Δ cells, GFP-Atg32 accumulated at the PAS in 39% (2 h) or 68% (4 h) of atg1Δ hog1Δ cells, which was almost similar to the extent of colocalization seen in atg1Δ cells (Fig. 6). This result suggested a defect in mitochondrial recruitment to the PAS in the slt2Δ, but not hog1Δ, mutant.

Figure 6.

Recruitment of Atg32 to the PAS is defective in the slt2Δ, but not the hog1Δ mutant. (A) Plasmid-driven GFP-Atg32 was transformed into atg1Δ (WHY001), atg1Δ slt2Δ (KDM1203), and atg1Δ hog1Δ (KDM1211) strains. Cells were grown to mid-log phase in SML, shifted to SD-N for 2 or 4 h, and stained with FM 4-64 to mark the vacuole. Representative pictures from single Z-section images are shown. DIC, differential interference contrast. Bars, 2.5 µm. (B) Quantification of Atg32 PAS localization. 12 Z-section images were projected and the percentage of cells that contained at least one GFP-Atg32 dot on the surface of the vacuole was determined. The SD was calculated from three independent experiments.

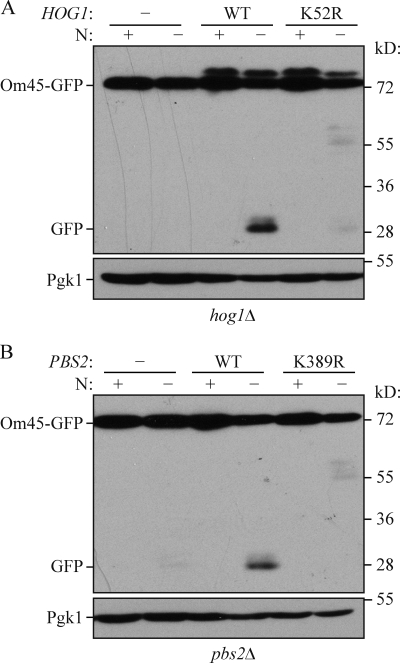

The kinase activities of Pbs2 and Hog1 are required for mitophagy

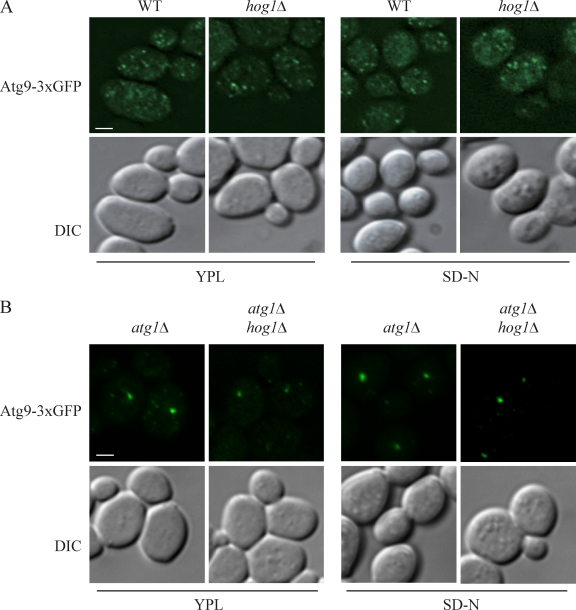

Among the autophagy core machinery proteins identified, Atg9 is the only transmembrane protein that is essential for the formation of autophagosomes. Atg9 cycles between the PAS and peripheral sites (Reggiori et al., 2004a,b). In mammalian cells, the MAPK p38, which is a homologue of Hog1, regulates autophagy by affecting Atg9 movement (Webber and Tooze, 2010). Therefore, we asked whether Hog1 in yeast might also affect Atg9 cycling. Accordingly, we first investigated the retrograde transport of Atg9 in the hog1Δ mutant. Like the wild-type cells, Atg9 displayed multiple dots both in vegetative (SML) or nitrogen starvation (SD-N) conditions, which indicated that Hog1 had no effect on Atg9 retrograde transport (Fig. 7 A). We then examined the anterograde transport of Atg9 by the TAKA (transport of Atg9 after knocking out ATG1) assay (Shintani and Klionsky, 2004). This is an epistasis analysis that relies on the accumulation of Atg9 at the PAS in the atg1Δ mutant background; mutants that are defective in anterograde movement of Atg9 to the PAS do not accumulate the protein at this site when combined with the atg1Δ mutation. However, Atg9 accumulated as a single dot in the atg1Δ hog1Δ mutant, similar to the result seen in the atg1Δ mutant (Fig. 7 B). This result indicated that, unlike p38, Hog1 is involved in mitophagy through a mechanism that does not affect Atg9 movement.

Figure 7.

Atg9 movement is unaffected in the hog1Δ mutant. (A and B) The localization of Atg9-3xGFP was tested in wild-type (JGY134) and hog1Δ (KDM1207) strains (A) and atg1Δ (JGY135) and atg1Δ hog1Δ (KDM1212) strains (B). Cells were cultured in growing (YPL medium) conditions and shifted to nitrogen starvation medium (SD-N) for 2 h. Cells were fixed and observed by fluorescence microscopy. Representative pictures from single Z-section images are shown. DIC, differential interference contrast. Bars, 2.5 µm.

Next, we asked whether the kinase activities of Pbs2 and Hog1 are necessary for mitophagy. As expected, introduction of the wild-type HOG1 and PBS2 genes complemented the mitophagy defect in hog1Δ and pbs2Δ cells, respectively (Fig. 8, A and B). In contrast, the kinase-dead mutants of Hog1 (K52R) and Pbs2 (K389R) were unable to recover mitophagy activity. Overall, these results suggest that upon activation by Pbs2, Hog1 phosphorylates a certain unidentified substrate(s), and that these signaling events play a significant role in mitophagy.

Figure 8.

Kinase-dead mutants of Hog1 and Pbs2 have defects in mitophagy. (A) The hog1Δ (KDM1307) or (B) pbs2Δ (KDM1309) cells were transformed with empty vector or a plasmid encoding either (A) wild-type (WT) Hog1 or a kinase-dead mutant (K52R), or (B) with empty vector or a plasmid encoding either wild-type Pbs2 or a kinase-dead mutant (K389R). (A and B) Om45-GFP processing was examined as described in Materials and methods.

As a final attempt to identify targets of these signaling pathways, we examined whether the Hog1 and Slt2 kinases had any effect on the activity of the Atg1 kinase. Atg1 autophosphorylation results in a molecular mass shift that can be detected by SDS-PAGE (Yeh et al., 2010). The slt2Δ and hog1Δ strains showed the same shift in mass for HA-Atg1 as seen in the wild-type strain (Fig. S3 A). We extended this analysis by examining Atg1 kinase activity using an in vitro assay with myelin basic protein as a substrate (Kamada et al., 2000). Atg1 kinase activity was reduced in the absence of Atg13 as expected, but there was no change in activity in the slt2Δ or hog1Δ mutants (Fig. S3 B), in agreement with the normal autophosphorylation activity. We then asked whether the absence of Slt2 or Hog1 affected Atg13 phosphorylation; Atg13 is highly phosphorylated in rich conditions, and partially dephosphorylated upon shift to nitrogen starvation (Scott et al., 2000). Again, there was essentially no difference in the phosphorylation status of Atg13 in the slt2Δ or hog1Δ mutants relative to the wild type (Fig. S3 C). Although the Slt2 and Hog1 kinases did not appear to affect the Atg1 or Atg13 proteins, we decided to examine the converse, and monitored the phosphorylation of Slt2 and Hog1 in an atg1Δ strain. Slt2 and Hog1 were phosphorylated after a 1- or 2-h shift to nitrogen starvation conditions, respectively, in the atg1Δ strain, similar to the result seen in the wild type (Fig. S3 D).

Discussion

MAPK-signaling pathways comprise components that play major roles in cellular metabolism and resistance to stress. The Slt2-signaling pathway participates in cell wall integrity, hypo-osmotic response, and ER stress and inheritance regulation (Levin, 2005; Scrimale et al., 2009; Babour et al., 2010), whereas the Hog1 signaling pathway is involved in hyper-osmotic response and the ER stress response (Westfall et al., 2004; Bicknell et al., 2010). In this paper, we have shown that Slt2 and Hog1 are involved in mitophagy, as both slt2Δ and hog1Δ cells showed severe defects in selective mitochondria degradation. Furthermore, the analysis of upstream components indicates that these kinases are involved in the Wsc1–Pkc1–Bck1–Mkk1/2–Slt2 and Ssk1–Pbs2–Hog1 signal transduction pathways, respectively. Both Slt2 and Hog1 are phosphorylated and remain in the cytosol during mitophagy, and none of the known downstream transcriptional factors have any apparent role in mitophagy. Bulk autophagy was unaffected in both slt2Δ and hog1Δ cells, indicating that these two signaling pathways do not act through the autophagy core machinery or by affecting overall autophagic flux.

Atg32 acts as an organelle-specific tag, and is critical for the recognition of mitochondria during mitophagy. Accordingly, the defect in Atg32 recruitment to the PAS in slt2Δ cells may explain why mitochondria could not be recognized, targeted, and transported to the PAS in the slt2Δ mutant. This defect together with the quick response of Slt2 phosphorylation suggested that a Slt2-dependent signaling event might play an early role in mitophagy induction. In contrast, no effect on Atg32 PAS localization in the hog1Δ mutant and a late pattern of Hog1 phosphorylation might be due to a role of Hog1 in a relatively late stage of mitophagy. Hog1-driven signaling was specific for mitophagy, whereas Slt2 also participated in pexophagy. A role for Slt2 in pexophagy was recently found by another group (Manjithaya et al., 2010); however, in that paper, a mitophagy defect was not detected in slt2Δ cells, whereas pexophagy was completely blocked, the latter being consistent with our results.

Both Hog1 and Slt2 were required for mitophagy, but only the latter for pexophagy. One explanation for the apparently more stringent regulation of mitophagy may be that mitochondria play a much more important role in cellular physiology in S. cerevisiae. This organism has evolved such that its metabolism favors fermentation, and unlike Pichia pastoris or Hansenula polymorpha it does not grow on methanol. Although S. cerevisiae can induce peroxisomes when grown in media with oleic acid as the sole carbon source, it otherwise retains relatively small numbers of this organelle. Accordingly, there may be relatively fewer mechanisms for regulating peroxisome degradation.

The Hog1, and possibly Slt2, MAPK-signaling pathway is conserved from yeast to mammals and its role in autophagy regulation also shows similarities, to some extent; in mammalian cells, the MAPKs JNK1, PKCδ, and p38 modulate autophagy (Ozpolat et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2008; Shahnazari et al., 2010; Webber and Tooze, 2010). Thus, the significant roles of Slt2 and Hog1 in mitophagy reveal an evolutionarily conserved function of MAPKs in autophagy control.

Materials and methods

Strains, media, and growth conditions

Yeast strains used in this paper are listed in Table I. Yeast cells were grown in rich (YPD; 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose) or synthetic minimal (SMD; 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% glucose, and auxotrophic amino acids and vitamins as needed) media. For mitochondria proliferation, cells were grown in lactate medium (YPL; 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% lactate) or synthetic minimal medium with lactate (SML; 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% lactate, and auxotrophic amino acids and vitamins as needed). Mitophagy was induced by shifting the cells to nitrogen starvation medium with glucose (SD-N; 0.17% yeast nitrogen base without ammonium sulfate or amino acids, and 2% glucose). For peroxisome induction, cells were grown in oleate medium (1% oleate, 5% Tween 40, 0.25% yeast extract, 0.5% peptone, and 5 mM phosphate buffer). Pexophagy was also triggered by transferring the cells to SD-N.

Table I.

Yeast strains used in this paper

| Name | Genotype | Reference |

| BY4742 | MATα his3Δ leu2Δ lys2Δ ura3Δ | Invitrogen |

| JGY134 | SEY6210 RFP-APE1::LEU2 ATG9-3xGFP::URA3 | This paper |

| JGY135 | SEY6210 RFP-APE1::LEU2 ATG9-3xGFP::URA3 atg1Δ::ble | This paper |

| KDM1003 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 mkk1Δ::HIS5 mkk2Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM1005 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 pbs2Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM1008 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 slt2Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM1015 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 hog1Δ::HIS5 | This paper |

| KDM1021 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 ssk1Δ::ble | This paper |

| KDM1022 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 sho1Δ::ble | This paper |

| KDM1023 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 wsc1Δ::ble | This paper |

| KDM1025 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 slt2Δ::KAN hog1Δ::HIS5 | This paper |

| KDM1101 | SEY6210 PEX14-GFP::KAN slt2Δ::URA3 | This paper |

| KDM1102 | SEY6210 PEX14-GFP::KAN hog1Δ::URA3 | This paper |

| KDM1203 | SEY6210 atg1Δ::HIS5 slt2Δ::ble | This paper |

| KDM1207 | SEY6210 RFP-APE1::LEU2 ATG9-3xGFP::URA3 hog1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM1211 | SEY6210 atg1Δ::HIS5 hog1Δ::ble | This paper |

| KDM1212 | SEY6210 RFP-APE1::LEU2 ATG9-3xGFP::URA3 atg1Δ::ble hog1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM1213 | SEY6210 slt2Δ::HIS5 | This paper |

| KDM1214 | SEY6210 hog1Δ::HIS5 | This paper |

| KDM1217 | SEY6210 HOG1-GFP::HIS5 | This paper |

| KDM1218 | SEY6210 SLT2-GFP::HIS5 | This paper |

| KDM1303 | SEY6210 OM45-GFP::TRP1 mkk2Δ::KAN mkk1Δ::HIS5 | This paper |

| KDM1305 | SEY6210 OM45-GFP::TRP1 slt2Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM1307 | SEY6210 OM45-GFP::TRP1 hog1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM1309 | SEY6210 OM45-GFP::TRP1 pbs2Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM1403 | SEY6210 pho13Δ pho8Δ60::HIS3 hog1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM1401 | SEY6210 pho13Δ pho8Δ60::HIS3 slt2Δ::URA3 | This paper |

| KDM2009 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 pkc1-2::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2011 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 pkc1-1::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2010 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 pkc1-3::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2012 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 pkc1-4::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2023 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 | This paper |

| KDM2024 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 wsc1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2025 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 wsc2Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2026 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 wsc3Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2027 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 wsc4Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2028 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 mid2Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2029 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 mtl1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2030 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 rlm1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2031 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 swi4Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2032 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 swi6Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2033 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 sko1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2034 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 smp1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2035 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 hot1Δ::KAN | This paper |

| KDM2036 | BY4742 OM45-GFP::HIS3 sln1-ts::KAN | This paper |

| KWY20 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 | (Kanki et al., 2009a) |

| KWY22 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 atg32Δ::KAN | (Kanki et al., 2009a) |

| KWY33 | SEY6210 pho8Δ::TRP1 pho13Δ::LEU2 pRS406-ADH1-COX4-pho8Δ60 bck1Δ::KAN | (Kanki et al., 2009a) |

| KWY51 | SEY6210 OM45-GFP::TRP1 bck1Δ::KAN | (Kanki et al., 2009a) |

| SEY6210 | MATα ura3-52 leu2-3,112 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 mel GAL | (Robinson et al., 1988) |

| TKYM130 | SEY6210 OM45-GFP::TRP1 atg32Δ::URA3 | (Kanki et al., 2009b) |

| TKYM22 | SEY6210 OM45-GFP::TRP1 | (Kanki and Klionsky, 2008) |

| TKYM67 | SEY6210 PEX14-GFP::KAN | (Kanki and Klionsky, 2008) |

| TKYM72 | SEY6210 PEX14-GFP::KAN atg1Δ::HIS5 | (Kanki and Klionsky, 2008) |

| TKYM203 | SEY6210 atg1Δ::HIS5 IDH1-RFP::KAN | (Kanki et al., 2009b) |

| UNY29 | SEY6210 atg13Δ::KAN atg1Δ::HIS5 | This paper |

| WHY001 | SEY6210 atg1Δ::HIS5 | (Shintani et al., 2002) |

| WLY176 | SEY6210 pho13Δ pho8Δ60::HIS3 | (Kanki et al., 2009a) |

| WLY192 | SEY6210 pho13Δ::KAN pho8Δ60::URA3 atg1Δ::HIS5 | (Kanki et al., 2009a) |

Plasmids and strains

pCuGFPAtg32(416) has been reported previously (Kanki et al., 2009b). In brief, the gene encoding GFP was inserted into the SpeI and XmaI restriction enzyme sites of pCu(416) to generate pCuGFP(416) (Kim et al., 2001). Then the ATG32 gene was amplified by PCR from the yeast genome and ligated into the EcoRI and SalI sites of pCuGFP(416) to construct pCuGFPAtg32(416). For other plasmids, we amplified the open reading frames along with 1 kb of upstream genomic DNA of the SLT2, PBS2, and HOG1 genes by PCR, and introduced the PCR fragments into pDONR221 by recombination-based cloning using the Gateway system (Invitrogen). The Hog1K52R and Pbs2K389R kinase-dead alleles were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the entry vectors. After sequencing, wild-type and kinase-dead alleles of HOG1 and PBS2 were separately introduced into the pAG416-ccdB-TAP destination vector (Addgene). Wild-type alleles of SLT2 and HOG1 were also introduced into the pDEST-vYFP destination vector (Ma et al., 2008).

Other reagents

The anti–phospho-Slt2 (phospho-p44/42 MAPK) and anti–phospho-Hog1 antibody (phospho-p38 MAPK) were from Cell Signaling Technology.

Fluorescence microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy, yeast cells were grown to OD600 ∼0.8 in SML selective medium. Cells were shifted to SD-N for nitrogen starvation, or to 39°C for heat shock stress, or 0.4 M NaCl was added into the medium for hyper-osmotic stress. The samples were then examined by microscopy (TH4-100, Olympus; or Delta Vision Spectris, Applied Precision) using a 100x objective at 30°C and pictures were captured with a CCD camera (CoolSnap HQ; Photometrics). The imaging medium was either SML or SD-N, as indicated for each figure. For each microscopy picture, 15 Z-section images were captured with a 0.4-µm distance between two neighboring sections. FM 4-64 (Invitrogen) was applied to stain the vacuolar membrane. For quantification of GFP-Atg32 dots, the stack of Z-section images was projected into a 2D image. Images were processed in Adobe Photoshop and prepared in Adobe Illustrator.

Additional assays

The Pho8Δ60, Pex14-GFP processing, Om45-GFP processing, mitoPho8Δ60 and Atg1 in vitro kinase assays were performed as described previously (Abeliovich et al., 2003; Shintani and Klionsky, 2004; Reggiori et al., 2005; Kanki et al., 2009a). For the alkaline phosphatase assay, two A600 equivalents of yeast cells were harvested and resuspended in 100 µl lysis buffer (20 mM Pipes, pH 7.0, 0.5%Triton X-100, 50 mM KCl, 100 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM MgSO4, 10 µM ZnSO4, and 1 mM PMSF). The cells were lysed by vortexing with glass beads for 5 min, 50 µl of extract was added to 450 µl reaction buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 0.4% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgSO4, and 1.25 mM nitrophenylphosphate), and samples were incubated for 15 min at 30°C before terminating the reaction by adding 500 µl of stop buffer (2 M glycine, pH 11). Production of nitrophenol was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 400 nm using a spectrophotometer (DU-640B; Beckman Coulter), and the nitrophenol concentration was calculated using Beer’s law with ε400 = 18,000 M−1 cm−1. Protein concentration in the extracts was measured with the Pierce BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and one activity unit was defined as nmol nitrophenol/min/mg protein.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the role of Sln1 in mitophagy. Fig. S2 provides additional data that demonstrate the movement of mitochondria to the PAS under mitophagy-inducing conditions. Fig. S3 shows that the regulatory functions of Hog1 and Slt2 are independent of the Atg1-Atg13 complex. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201102092/DC1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jiefei Geng (Harvard University, Massachusetts) for providing strains, Dr. Usha Nair for providing plasmids, and Dr. Zhifen Yang for technical support.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Public Health Service grant GM53396 to D.J. Klionsky.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- Atg

- autophagy-related

- Cvt

- cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PAS

- phagophore assembly site

References

- Abeliovich H., Zhang C., Dunn W.A., Jr, Shokat K.M., Klionsky D.J. 2003. Chemical genetic analysis of Apg1 reveals a non-kinase role in the induction of autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:477–490 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Monge R., Carvaihlo S., Nombela C., Rial E., Pla J. 2009. The Hog1 MAP kinase controls respiratory metabolism in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Microbiology. 155:413–423 10.1099/mic.0.023309-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba M., Osumi M., Scott S.V., Klionsky D.J., Ohsumi Y. 1997. Two distinct pathways for targeting proteins from the cytoplasm to the vacuole/lysosome. J. Cell Biol. 139:1687–1695 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babour A., Bicknell A.A., Tourtellotte J., Niwa M. 2010. A surveillance pathway monitors the fitness of the endoplasmic reticulum to control its inheritance. Cell. 142:256–269 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicknell A.A., Tourtellotte J., Niwa M. 2010. Late phase of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response pathway is regulated by Hog1 MAP kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 285:17545–17555 10.1074/jbc.M109.084681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster J.L., de Valoir T., Dwyer N.D., Winter E., Gustin M.C. 1993. An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science. 259:1760–1763 10.1126/science.7681220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budovskaya Y.V., Stephan J.S., Reggiori F., Klionsky D.J., Herman P.K. 2004. The Ras/cAMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathway regulates an early step of the autophagy process in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279:20663–20671 10.1074/jbc.M400272200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C.L., Thorsness P.E. 1998. Escape of mitochondrial DNA to the nucleus in yme1 yeast is mediated by vacuolar-dependent turnover of abnormal mitochondrial compartments. J. Cell Sci. 111:2455–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-L., Lin H.H., Kim K.-J., Lin A., Forman H.J., Ann D.K. 2008. Novel roles for protein kinase Cdelta-dependent signaling pathways in acute hypoxic stress-induced autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 283:34432–34444 10.1074/jbc.M804239200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong H., Nair U., Geng J., Klionsky D.J. 2008. The Atg1 kinase complex is involved in the regulation of protein recruitment to initiate sequestering vesicle formation for nonspecific autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 19:668–681 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng J., Nair U., Yasumura-Yorimitsu K., Klionsky D.J. 2010. Post-Golgi Sec proteins are required for autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21:2257–2269 10.1091/mbc.E09-11-0969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn J.S., Thiele D.J. 2002. Regulation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Slt2 kinase pathway by the stress-inducible Sdp1 dual specificity phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:21278–21284 10.1074/jbc.M202557200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinisch J.J., Lorberg A., Schmitz H.P., Jacoby J.J. 1999. The protein kinase C-mediated MAP kinase pathway involved in the maintenance of cellular integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 32:671–680 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01375.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada Y., Funakoshi T., Shintani T., Nagano K., Ohsumi M., Ohsumi Y. 2000. Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J. Cell Biol. 150:1507–1513 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T., Klionsky D.J. 2008. Mitophagy in yeast occurs through a selective mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 283:32386–32393 10.1074/jbc.M802403200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T., Wang K., Baba M., Bartholomew C.R., Lynch-Day M.A., Du Z., Geng J., Mao K., Yang Z., Yen W.-L., Klionsky D.J. 2009a. A genomic screen for yeast mutants defective in selective mitochondria autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20:4730–4738 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T., Wang K., Cao Y., Baba M., Klionsky D.J. 2009b. Atg32 is a mitochondrial protein that confers selectivity during mitophagy. Dev. Cell. 17:98–109 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kamada Y., Stromhaug P.E., Guan J., Hefner-Gravink A., Baba M., Scott S.V., Ohsumi Y., Dunn W.A., Jr, Klionsky D.J. 2001. Cvt9/Gsa9 functions in sequestering selective cytosolic cargo destined for the vacuole. J. Cell Biol. 153:381–396 10.1083/jcb.153.2.381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky D.J., Emr S.D. 1989. Membrane protein sorting: biosynthesis, transport and processing of yeast vacuolar alkaline phosphatase. EMBO J. 8:2241–2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky D.J., Cueva R., Yaver D.S. 1992. Aminopeptidase I of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is localized to the vacuole independent of the secretory pathway. J. Cell Biol. 119:287–299 10.1083/jcb.119.2.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft C., Deplazes A., Sohrmann M., Peter M. 2008. Mature ribosomes are selectively degraded upon starvation by an autophagy pathway requiring the Ubp3p/Bre5p ubiquitin protease. Nat. Cell Biol. 10:602–610 10.1038/ncb1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin D.E. 2005. Cell wall integrity signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:262–291 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.262-291.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Bharucha N., Dobry C.J., Frisch R.L., Lawson S., Kumar A. 2008. Localization of autophagy-related proteins in yeast using a versatile plasmid-based resource of fluorescent protein fusions. Autophagy. 4:792–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjithaya R., Jain S., Farré J.C., Subramani S. 2010. A yeast MAPK cascade regulates pexophagy but not other autophagy pathways. J. Cell Biol. 189:303–310 10.1083/jcb.200909154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N., Levine B., Cuervo A.M., Klionsky D.J. 2008. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 451:1069–1075 10.1038/nature06639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda T., Matsuura A., Wada Y., Ohsumi Y. 1995. Novel system for monitoring autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 210:126–132 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K., Kondo-Okamoto N., Ohsumi Y. 2009. Mitochondria-anchored receptor Atg32 mediates degradation of mitochondria via selective autophagy. Dev. Cell. 17:87–97 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozpolat B., Akar U., Mehta K., Lopez-Berestein G. 2007. PKC δ and tissue transglutaminase are novel inhibitors of autophagy in pancreatic cancer cells. Autophagy. 3:480–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F., Tucker K.A., Stromhaug P.E., Klionsky D.J. 2004a. The Atg1-Atg13 complex regulates Atg9 and Atg23 retrieval transport from the pre-autophagosomal structure. Dev. Cell. 6:79–90 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00402-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F., Wang C.-W., Nair U., Shintani T., Abeliovich H., Klionsky D.J. 2004b. Early stages of the secretory pathway, but not endosomes, are required for Cvt vesicle and autophagosome assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:2189–2204 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F., Monastyrska I., Shintani T., Klionsky D.J. 2005. The actin cytoskeleton is required for selective types of autophagy, but not nonspecific autophagy, in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:5843–5856 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J.S., Klionsky D.J., Banta L.M., Emr S.D. 1988. Protein sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of mutants defective in the delivery and processing of multiple vacuolar hydrolases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:4936–4948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H., Tatebayashi K. 2004. Regulation of the osmoregulatory HOG MAPK cascade in yeast. J. Biochem. 136:267–272 10.1093/jb/mvh135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S.V., Nice D.C., III, Nau J.J., Weisman L.S., Kamada Y., Keizer-Gunnink I., Funakoshi T., Veenhuis M., Ohsumi Y., Klionsky D.J. 2000. Apg13p and Vac8p are part of a complex of phosphoproteins that are required for cytoplasm to vacuole targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25840–25849 10.1074/jbc.M002813200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrimale T., Didone L., de Mesy Bentley K.L., Krysan D.J. 2009. The unfolded protein response is induced by the cell wall integrity mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade and is required for cell wall integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20:164–175 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahnazari S., Yen W.-L., Birmingham C.L., Shiu J., Namolovan A., Zheng Y.T., Nakayama K., Klionsky D.J., Brumell J.H. 2010. A diacylglycerol-dependent signaling pathway contributes to regulation of antibacterial autophagy. Cell Host Microbe. 8:137–146 10.1016/j.chom.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani T., Klionsky D.J. 2004. Cargo proteins facilitate the formation of transport vesicles in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279:29889–29894 10.1074/jbc.M404399200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani T., Huang W.-P., Stromhaug P.E., Klionsky D.J. 2002. Mechanism of cargo selection in the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. Dev. Cell. 3:825–837 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00373-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D.C. 2005. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39:359–407 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber J.L., Tooze S.A. 2010. New insights into the function of Atg9. FEBS Lett. 584:1319–1326 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Pattingre S., Sinha S., Bassik M., Levine B. 2008. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Mol. Cell. 30:678–688 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall P.J., Ballon D.R., Thorner J. 2004. When the stress of your environment makes you go HOG wild. Science. 306:1511–1512 10.1126/science.1104879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z., Klionsky D.J. 2007. Autophagosome formation: core machinery and adaptations. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:1102–1109 10.1038/ncb1007-1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Geng J., Yen W.-L., Wang K., Klionsky D.J. 2010. Positive or negative roles of different cyclin-dependent kinase Pho85-cyclin complexes orchestrate induction of autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. 38:250–264 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh Y.Y., Wrasman K., Herman P.K. 2010. Autophosphorylation within the Atg1 activation loop is required for both kinase activity and the induction of autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 185:871–882 10.1534/genetics.110.116566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen W.-L., Klionsky D.J. 2008. How to live long and prosper: autophagy, mitochondria, and aging. Physiology (Bethesda). 23:248–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorimitsu T., Zaman S., Broach J.R., Klionsky D.J. 2007. Protein kinase A and Sch9 cooperatively regulate induction of autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 18:4180–4189 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]