Abstract

The pattern of the large sensory bristles on the notum of Drosophila arises as a consequence of the expression of the achaete and scute genes. The gene u-shaped encodes a novel zinc finger that acts as a transregulator of achaete and scute in the dorsal region of the notum. Viable hypomorphic u-shaped mutants display additional dorsocentral and scutellar bristles that result from overexpression of achaete and scute. In contrast, overexpression of u-shaped causes a loss of achaete–scute expression and consequently a loss of dorsal bristles. The effects on the dorsocentral bristles appear to be mediated through the enhancer sequences that regulate achaete and scute at this site. The effects of u-shaped mutants are similar to those of a class of dominant alleles of the gene pannier with which they display allele-specific interactions, suggesting that the products of both genes cooperate in the regulation of achaete and scute. A study of the sites at which the dorsocentral bristles arise in mosaic u-shaped nota, suggests that the levels of the u-shaped protein are crucial for the precise positioning of the precursors of these bristles.

Keywords: Drosophila, u-shaped, zinc finger protein, bristle pattern, achaete, scute

The stereotyped positions of the large sensory bristles, or macrochaetes, of the Drosophila imago, provide a good model system for the study of pattern formation, and the analysis of genetic variants has allowed the identification of specific genes involved in the generation of this pattern (Lindsley and Zimm 1992). Each bristle organ is unique and develops within the imaginal disc from a single precursor cell, the sensory organ mother cell. Sensory mother cells (SMCs) arise as the result of a series of sequential steps. First, the competence to become a SMC is conferred to groups of cells at defined positions that prefigure the site of each future bristle. These cells are characterized by the localized expression of the proneural genes achaete (ac) and scute (sc), two members of the ac–sc complex (AS–C; Ghysen and Dambly-Chaudiere 1988; Campuzano and Modolell 1992). ac and sc encode transcriptional factors of the basic helix–loop–helix family first isolated in Drosophila whose activity confers neural potential to the cells (Villares and Cabrera 1987; Gonzalez et al. 1989). Loss of ac and sc causes a loss of all bristles on the thorax, whereas ectopic expression of these genes results in the formation of additional or ectopic bristles (Garcia-Bellido 1979; Balcells et al. 1988; Garcia-Alonso and Garcia-Bellido 1988). Neural potential is then progressively refined to a single cell, the future SMC within the proneural cluster by means of cell–cell interactions mediated by the neurogenic genes. This process is called lateral inhibition and involves an inhibitory signal from the nascent precursor that prevents the remaining cells of the cluster from becoming SMCs (for review, see Simpson 1990; Campos-Ortega and Jan 1991).

Proneural clusters arise in a precise spatial and temporal pattern that defines the positions at which each SMC and its corresponding macrochaete will arise (Romani et al. 1989; Cubas et al. 1991; Skeath and Carroll 1991). This dynamic expression pattern is controlled through the action of cis-regulatory sequences that modulate the expression of both ac and sc and that are scattered throughout the length of the AS–C (Ruiz-Gomez and Modolell 1987; Ruiz-Gomez and Ghysen 1993; Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1995). It is thought that in the imaginal epithelium, a prepattern of asymmetrically distributed factors regulate expression of ac and sc via these enhancer sequences.

Few factors regulating transcription of ac and sc have been identified, including the products of the genes hairy, extramacrochaetae, and those of the iroquois complex, araucan and caupolican. Hairy and Extramacrochaetae are negative regulators and encode products that belong to the family of proteins bearing helix–loop–helix motifs (Rushlow et al. 1989; Ellis et al. 1990; Garrell and Modolell 1990). Hairy binds to ac upstream regulatory sequences and acts as a transcriptional repressor (Skeath and Carroll 1991; Ohsako et al. 1994; Van Doren et al. 1994), but Extramacrochaetae is thought to down-regulate ac and sc function by protein association (Van Doren et al. 1991; Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1995). The recently described araucan and caupolican proteins are transcriptional activators that belong to a novel family of homeoproteins and that regulate both sensory organ development and wing vein formation (Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1996).

The gene pannier (pnr) is also required for the spatial regulation of ac and sc in imaginal discs and encodes a protein with two functional domains—a zinc finger domain with homology to the vertebrate transcription factor GATA-1 and a domain comprising two putative amphipathic helices (Ramain et al. 1993). A number of alleles of pnr have been described causing either a loss of ac–sc expression at some sites and the corresponding loss of specific bristles, or ectopic expression of ac–sc and the formation of additional bristles (Heitzler et al. 1996b). A class of dominant alleles (collectively called pnrD), associated with lesions in the zinc finger domain, display an overexpression of ac and sc and the development of extra thoracic bristles. Here we describe mutants of the u-shaped (ush) gene, isolated during a screen for second-site modifiers of the pnrD phenotype (P. Heitzler, unpubl.). Alleles of ush causing a loss of function act as dominant enhancers of pnrD heterozygotes, resulting in an increase in the number of ectopic thoracic bristles. On the other hand, three copies of the wild-type ush gene suppress the pnrD/+ phenotype. This suggests that pnr and ush might act in the same developmental pathway to regulate the ac and sc genes.

A morphogenetic study of ush mutants and the molecular cloning of this gene is described. The bristle pattern of the viable recessive alleles of ush is similar to that of the pnrD alleles. We show that the additional bristles on the dorsal part of the thorax are associated with the overexpression of ac and sc in the corresponding proneural clusters. In contrast, ectopic expression of ush causes a loss of ac–sc expression that correlates with a loss of the corresponding dorsal bristles. ush encodes a novel zinc finger factor that has a role in the regulation of the spatial expression of ac and sc. The effects on the dorsocentral bristles appear to be mediated through the enhancer sequences that regulate ac and sc expression at the presumptive dorsocentral site in the thoracic imaginal disc.

Results

Allele-specific interactions between pnr and ush mutants

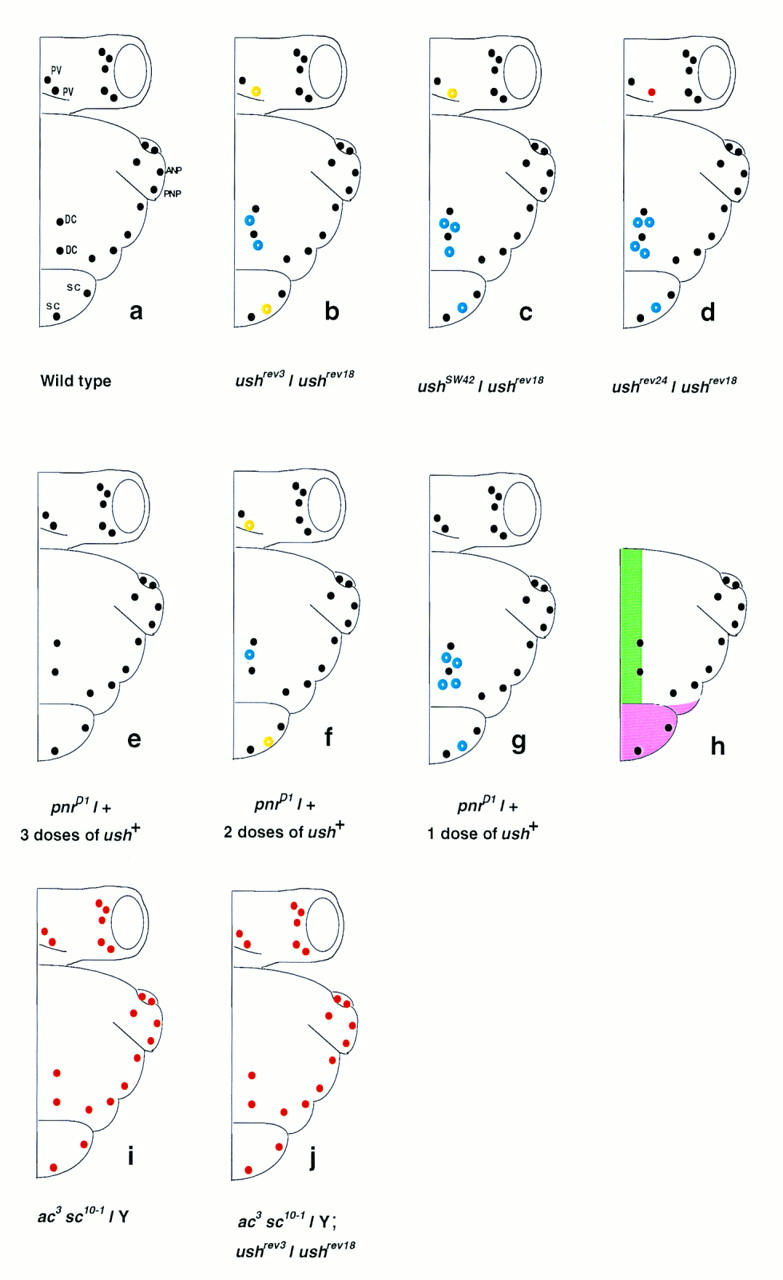

A number of mutant alleles at the pnr locus have been described including a class of dominant alleles (collectively called pnrD) associated with overexpression of ac–sc and additional dorsocentral bristles (Ramain et al. 1993). This phenotype is similar to that of viable ush mutants and, furthermore, both ush hypomorphs and pnrD heterozygotes lack the postvertical bristle on the head (Heitzler et al. 1996b). The phenotype of flies heterozygous for pnrD mutants is strongly modified by the dosage of ush+ (Fig. 1). A single copy of ush+ causes a dramatic increase in the number of dorsocentral bristles, whereas three copies suppress the pnrD phenotype entirely. This genetic interaction is restricted to the pnrD class of alleles, no other pnr mutants are sensitive to the amount of ush product (P. Heitzler, unpubl.).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the bristle patterns on the head and thorax of different mutant combinations of ush. The wild-type pattern is shown in a. In ush mutants, the dorsocentral bristles (DC) and the scutellar bristles (SC) of the thorax and the postvertical bristle (PV) on the head are the most frequently affected. The rest of the bristle pattern is normal. For each genotype, at least 30 hemithoraces were examined. Bristles present > 50% of the time are represented as black dots (wild-type positions) and blue circles (ectopic bristles), those present 10%–50% of the time are represented as yellow circles, and those present <10% of the time as red dots. (a) ANP and PNP are anterior and posterior notopleural bristles, respectively. (b–d) Three viable combinations forming an allelic series for the number of DC and SC bristles of the thorax and the PV on the head (see text). ushrev18 is a deficiency uncovering several genes, including ush, and will be called ush−. An allele specific interaction exists between ush and pnrD mutants (e–g). pnrD/+ flies (f) display additional bristles (DC and SC) and loss of PV bristles (Ramain et al. 1993), a phenotype that is suppressed by three doses of ush+ (e) or enhanced when only one copy of ush+ (g) is present in these flies. The thoracic territories affected by the lack of ush function as revealed by clonal analysis (see text) are presented in h. The pink area denotes a territory where ush is required for cell viability and the green area denotes a territory where ush is required for the normal positioning of the DC bristles, part of this territory is also required for the fusion of the dorsal midline. When both ac and sc are nonfunctional, as in ac3 sc10-1 flies, no bristles form whether or not ush is present (j and i).

ush is required for the pattern of bristles on the dorsal notum

Mutants in the gene ush and their embryonic recessive lethal phenotype were first described by Nüsslein-Volhard et al. (1984). In ush null embryos the germ band fails to retract and lateral fusion occurs between anterior and posterior ectoderm (R.P. Ray, unpubl.). A large number of mutant alleles of ush have been isolated and include hypomorphic mutants that affect the pattern of bristles on the head and thorax (P. Heitzler, unpubl.). Viable transallelic combinations of ush mutants display additional dorsocentral and scutellar bristles on the notum and a loss of postvertical bristles on the head (Figs. 1 and 2B). They form an allelic series for the number of dorsocentral (DC), scutellar (SC), and postvertical (PV) bristles [e.g., the number of bristles per hemithorax/head was found to be (DC) 4.59 ± 0.18, (SC) 2.44 ± 0.09, and (PV) 0.72 ± 0.08 for ushrev3/ush−; (DC) 5.44 ± 0.25, (SC) 2.59 ± 0.10, and (PV) 0.53 ± 0.09 for ushSW42/ush−; (DC) 6.27 ± 0.14, (SC) 2.67 ± 0.10, and (PV) 0.15 ± 0.06 for ushrev24/ush−. Wild-type flies invariably bear two DC, two SC, and one PV).

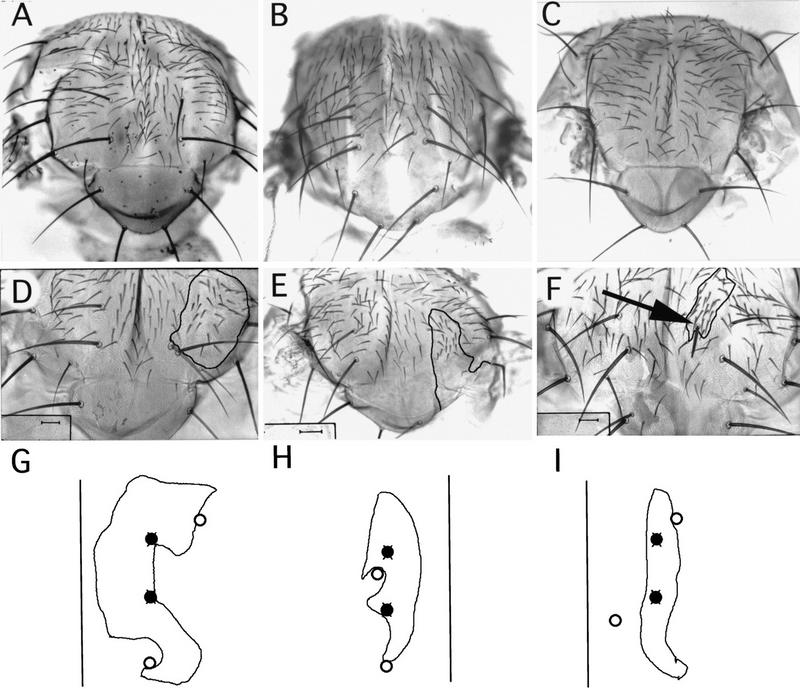

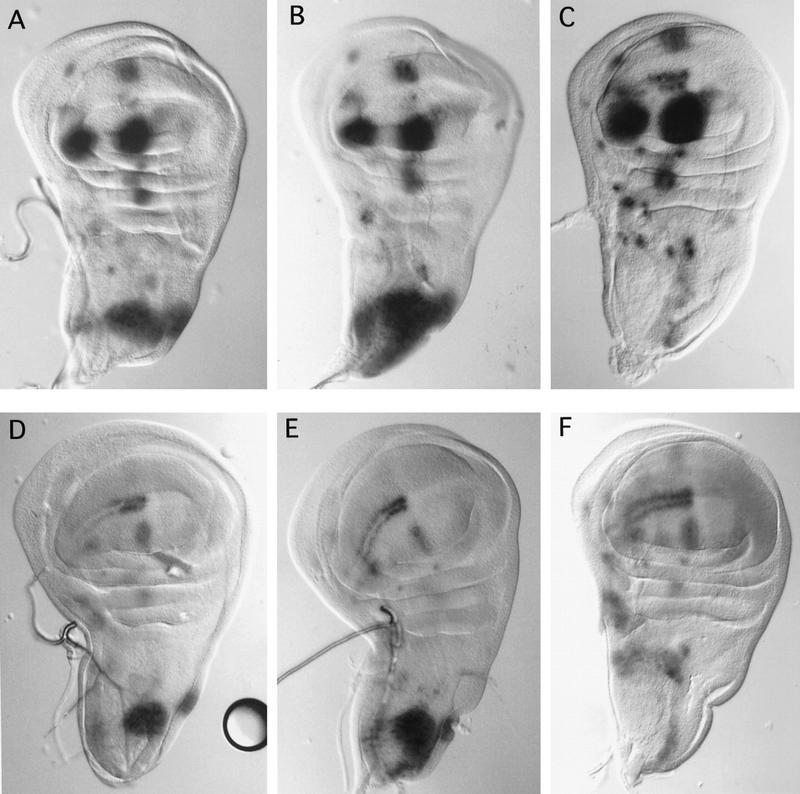

Figure 2.

The notal bristle phenotypes seen after a loss or an excess of ush expression. In the dorsocentral area of wild-type animals, two DC macrochaetes form in each hemithorax (A), whereas ush hypomorphic loss-of-function mutants display an excess of DC macrochaetes (ushrev24/ush− is shown in B). In contrast, overexpression of ush leads to loss of the DC bristles (hs–ush is shown in C). Absence of ush function also affects the formation of DC bristles, as revealed in clones of cells mutant for null alleles (D–F). Clones of mutant cells were generated during the larval stages (see Materials and Methods for details and complete genotypes). The mosaic border of the clones is indicated by a black line (D–F). A clone mutant for ushTgR + 1 (D) shows the formation of wild-type DC bristles that are displaced from the normal site and have formed at the borderline separating wild-type and mutant cells. In large clones encompassing the entire dorsocentral region, no DC bristles form (E). However, ush function is not required for the construction of bristles in this area because occasionally an additional mutant DC bristle develops (arrow in F). (G–I) Drawings of clones situated in the dorso-central area. (○) Bristles of the wild-type genotype that have formed at ectopic positions at the borders of the mutant clones; (•) the normal positions at which these bristles should have been situated.

To look at the complete loss of function of ush on the notum, we produced clones of cells mutant for the null alleles ushVX22, ushTgR + 1, and ushE6 (see Materials and Methods). All three resulted in similar phenotypes and affected the development of the dorsal half of the notum only, clones in the lateral part of the notum differentiated normally (Fig. 1). Clones extending into the scutellum fail to differentiate, generating large gaps in this region. Consequently, mutant scutellar bristles are never observed. Clones touching the dorsal midline are associated with a cleft in the thorax, whereas clones extending into the dorsocentral area are associated with absence or abnormal positioning of the dorsocentral bristles. From a study of 54 clones, the anterior dorsocentral bristle was found to be missing in 22 cases (41%), the posterior dorsocentral in 14 (26%; Fig. 2E). Nevertheless four dorsocentral bristles were of the mutant genotype showing that ush is not required for the construction of these bristles (Fig. 2F). In contrast, additional dorsocentral bristles were observed in only 17 cases (31%; 5 anterior and 12 posterior). Mutant bristles, when they do form, are never found at the correct locations characteristic of the wild-type flies, but are displaced to nearby positions.

Remarkably, in almost all cases of mosaicism in the dorsocentral area, the dorsocentral bristles formed by wild-type cells were also found to be displaced from their normal positions (Fig. 2D). Frequently, wild-type bristles are found on the mosaic border between mutant and wild-type cells. We counted 26 wild-type bristles in the dorsocentral region that were located precisely on the mosaic border. Furthermore, another 29 wild-type bristles, also displaced from their normal positions, were located a short distance away from the clone border outside the mutant territory. Therefore, there seems to be a nonautonomous effect of the mutant cells on the position at which wild-type bristles will form. Taken together, these results suggest that the position at which the dorsocentral bristles form may be dependent on the relative levels of ush product.

To investigate these observations further, animals mosaic for the viable hypomorphic allele ushrev24 were generated. In these mosaics, wild-type ush+ cells are juxtaposed to cells containing a reduced amount of Ush. In cases where the mosaic borderline fell within the dorsocentral territory, 30 bristles were located precisely on the clone border and nearly all of these were displaced from the normal positions for these bristles. In contrast, only five mutant dorsocentral bristles were situated within the clone itself. Unlike the null mutant clones, in ushrev24 mosaics, 25 (83%) of the bristles at the border were of the mutant genotype. We conclude that both the number and the position of dorsocentral bristles is dependent on the levels of ush product.

ush is expressed in the dorsal part of the thoracic imaginal disc

To determine the location of ush transcripts in the thoracic epithelium, we performed in situ hybridization with a digoxygenin-labeled ush cDNA probe (see below) in late third-instar imaginal discs. Expression of ush appears to be restricted to specific domains (Fig. 3D). Staining is detected in territories corresponding to the future dorsal-most region of the thorax, as well as in part of the hinge region and the posterior region of the pleura. In the hinge region, ush expression is found in a domain comprising the sites of appearance of the anterior notal wing process and the proximal tegula, expanding up to the border where anterior and posterior notopleural bristles develop (ANP and PNP in Fig. 1). In the dorsal part of the notum, staining covers the site of appearance of the scutellar bristles and extends to the border of the site at which the dorsocentral bristles form. Therefore, in the notum, the area of ush expression corresponds well with the region where ush is required for normal development. In contrast, no apparent phenotype has been detected in the hinge and the pleura in ush mutants, suggesting that activity of the gene is not essential at these sites.

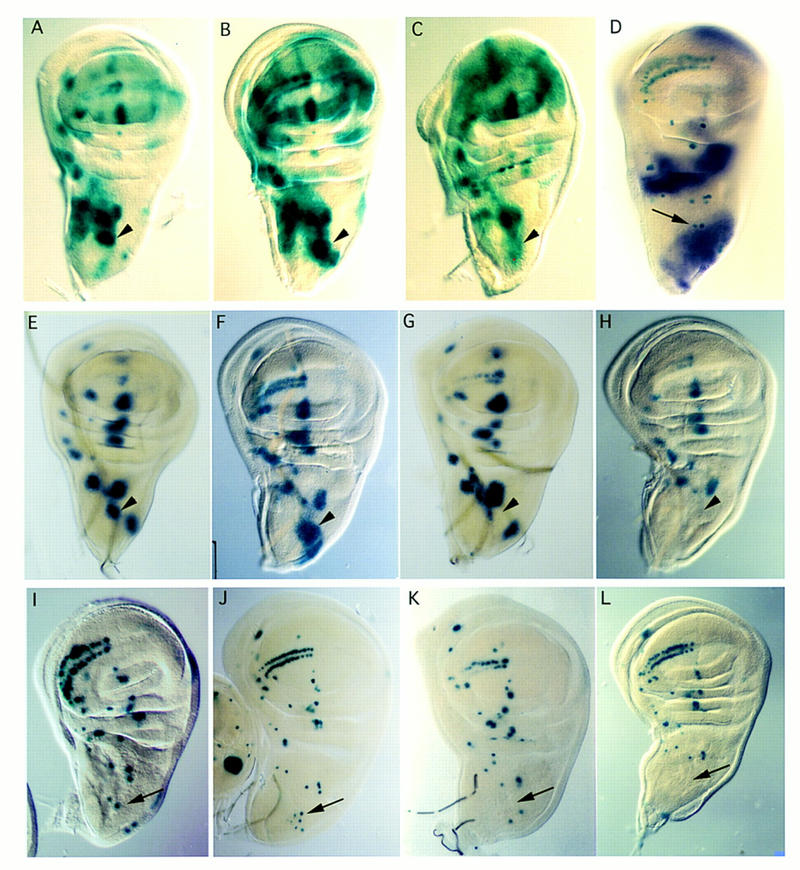

Figure 3.

Analysis of the formation of bristle precursors in ush mutants and after overexpression of ush, and the spatial expression of ush transcripts. Expression of ac and sc was followed by using the enhancer trap lines ac–lacZ (A–C) and sca–lacZ (E–H), which are expressed in the proneural clusters (see text). The position of the macrochaete precursors was studied with the enhancer trap line marker A101 (D,I,J,K,L). Wing discs were dissected from late third-instar mutant and wild-type larvae. Wild-type discs are shown in A, E, and I. Arrowheads in A–C and E–G point to the DC cluster detected by both enhancer trap lines, and arrows point to the DC precursor cells in D and I–L. Many more cells express ac–lacZ (B) and sca–lacZ (F) around the dorsocentral site in ushrev24/ushrev18, and staining extends into the scutellar region where more scutellar bristles develop in this genotype. A cluster of DC precursors arises in ushSW42/ushTgR + 1 mutant discs (arrow in J). In contrast, when ush is overexpressed using either a hs–ush (C,G,K) or UAS–ush driven by the GAL4 line pnrMD237 (H,L), the reduction of ac–lacZ (C) and the loss of expression of sca–lacZ (G) at the dorsocentral site indicate a severe reduction of ac–sc expression in the DC proneural cluster. No A101-positive cells (arrow) are seen at the dorsocentral site in hs–ush (K) and pnrMD237/UAS–ush (L) discs. However, in hs–ush flies, the scutellar bristles develop (see Fig. 2C) and A101 lacZ staining is seen in the bristle precursors (K), although they fail to appear in the pnrMD237/UAS–ush animals (L). (D) The in situ expression pattern of ush in the wing disc as revealed by digoxygenin-labeled probes. Expression is strong at the dorsal side including the scutellar territory and fades rapidly at the border of the area from which the dorsocentral bristles arise. Expression is also detected in the hinge region and in the presumptive region of the posterior pleura. The arrow points to dorsocentral precursors simultaneously labeled with A101.

The additional bristles formed in ush hypomorphic mutants result from overexpression of ac and sc

Formation of the thoracic sensory bristles is known to result from expression of the ac and sc genes and so we investigated the relationship between ush and ac–sc. As the effects of ush are strongest on the two dorsocentral macrochaetes, we focused our analysis on these bristles. Several lines of evidence suggest that the effects of ush are mediated by ac and sc. First, a synergism between ac–sc and ush is observed—animals heterozygous for both a deletion of ush and a deletion of the AS–C lack the posterior vertical bristles on the head (PV, see Fig. 1). Second, ac–sc mutants are epistatic over ush for the bristle phenotype—in the absence of ac–sc function, no sensory organs develop even in ush mutant flies (Fig. 1). This indicates that Ush functions before Ac and Sc. The additional macrochaetes seen in ush mutants may be therefore be attributable to overexpression of ac and sc.

To follow expression of ac and sc, we made use of the two transgenes ac–lacZ and scabrous (sca)–lacZ (Mlodzik et al. 1990; Martinez and Modolell 1991). The ac–lacZ transgene, which contains the 3.8-kb ac promotor region fused to the lacZ gene, expresses lacZ weakly in proneural clusters attributable to activation by the endogenous Ac and Sc proteins (Martinez and Modolell 1991; Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1995; Fig. 3A). The sca–lacZ line contains a lacZ insert in the sca gene, which is known to be a direct target for Ac and Sc. It shows a pattern of expression similar to that of ac and sc in the thoracic discs and ectopic expression of either ac or sc has been shown to induce ectopic expression of sca (Mlodzik et al. 1990; Fig. 3E). For one allelic mutant combination, we also looked for an antibody against Ac and observed a similar expression pattern. We have also followed development of the SMCs using A101, a lacZ insert in the neuralized gene, which is expressed in all sensory organs precursors (Fig. 3I; Boulianne et al. 1991).

In hypomorphic ush mutants, the excess of dorsocentral bristles correlates with the segregation of an excess of SMCs (Fig. 3J). Moreover, comparison between the dorsocentral region of wild-type and ush mutant discs, reveals a much larger territory of expression of ac–lacZ and sca–lacZ (Fig. 3B,F) in the mutants, which extends as far as the scutellum region. Altogether, these observations indicate that overexpression of ac and sc genes is responsible for the excess of bristles formed in the ush mutants.

Overexpression of ush leads to down-regulation of ac and sc and a loss of bristles

The domain of expression of ush extends from the dorsal midline of the thorax to the border of the site of formation of the dorsocentral macrochaetes. Although the number and position of these bristles is affected strongly in ush mutants, ush expression is only detectable at a low level at the site of the dorsocentral precursors themselves, suggesting that the levels of ush product in this area may have a determining role. To test this, we have looked at the consequences on the development of these bristles of a higher level of ush expression.

To overexpress ush, we generated transgenic flies carrying the ush cDNA under the control of a heat shock promotor and expressed ush ubiquitously during the period of time when the bristle precursors are determined. Overexpression of ush in imaginal thoracic discs during the third-larval stage up to early pupariation (see Materials and Methods) leads to the loss of dorsocentral bristles (Fig. 2C). The precursors for these bristles could not be detected in corresponding discs stained for A101 (Fig. 3K) and levels of ac–sc activity were low as shown by the loss of LacZ expression of the ac–lacZ and sca–lacZ inserts (Fig. 3C,G). Using the GAL4–upstream activating sequence (UAS) system (Brand and Perrimon 1993) we also expressed Ush in a large domain in the dorsal thorax corresponding to that of the pnr gene (Ramain et al. 1993). The GAL4 line pnrMD237 (Calleja et al. 1996; Heitzler et al. 1996b) was used to drive UAS–ush expression in the dorsal half of the notum, and this resulted in a loss of sca–lacZ expression in the dorsocentral proneural cluster, a loss of the dorsocentral precursor cells and a subsequent loss of dorsocentral bristles (Fig. 3H,L). Therefore overexpression of ush in the dorsocentral territory of the notum prevents formation of the dorsocentral macrochaetes.

ush acts through the dorsocentral enhancer of ac and sc

The results presented in the preceding section suggest that ush may regulate the expression of ac–sc at the dorsocentral site. The dorsocentral proneural cluster of ac–sc expression is known to depend on enhancer sequences (the DC enhancer) located 4.0–9.8 kb upstream of the ac transcription start (Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1995). To test whether the effects of ush are dependent on these sequences, we have examined the consequences of both loss of function and overexpression of ush on lacZ expression driven by the DC enhancer, using the Dc–ac2 and DC–3.2 lines described by Gomez-Skarmeta et al. (1995). Expression of both of these transgenes is increased in discs mutant for hypomorphic ush alleles and extends over a wider area when compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 4B,E). In contrast, ectopic expression of ush (UAS–ush driven by pnrMD237) resulted in a loss of the dorsocentral cluster of lacZ expressing cells in thoracic discs from the Dc–ac2 or DC–3.2 lines (Fig. 4C,F). These observations are consistent with a regulatory role for ush in the expression of ac and sc in the dorsocentral proneural cluster.

Figure 4.

ush regulates ac and sc expression through a dorsocentral-specific enhancer element. The dorsocentral specific enhancer element drives lacZ expression in the dorsocentral region of the thoracic discs (Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1995). lacZ staining is shown in thoracic discs with both the DC–enhancer–sc–lacZ (A–C) and the DC–enhancer–ac–lacZ (D–F). Compared with wild-type discs (A,D), lacZ expression detected in ushSW42/ushTgR + 1 mutant wing discs (B,E) in the dorsocentral area is stronger and covers a larger domain, whereas it is almost absent when ush is overexpressed (pnrMD237/UAS–ush) (C,F).

Molecular cloning of the ush locus

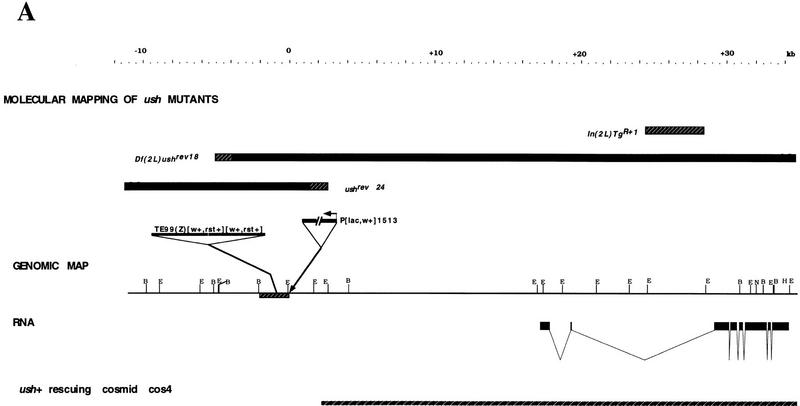

To isolate the ush gene, we made use of the enhancer trap line 1513 (L. Seugnet and M. Haenlin, unpubl.), which behaves as a weak ush allele (ush1513). DNA surrounding the ush1513 P[lacZ] element was obtained by the plasmid rescue technique (see Materials and Methods) and the resulting fragments were used to probe cosmid and λ phage genomic libraries. The location of this DNA in the ush region (21C), was confirmed by hybridization to salivary gland polytene chromosomes (data not shown). Figure 5 shows a map of ∼40 kb surrounding the ush1513 insertion (at position +0 kb on the map). Southern analysis revealed that two mutants generated by mobilization of the P[lacZ] insert, ushrev24 and ushrev18, were each associated with deletions starting from the P insertion point and expanding distally and proximally to the centromere, respectively. In ushrev24, which is a viable hypomorphic allele displaying a phenotype of an excess of bristles, sequences from position +2 kb leftward on the map are deleted. The ushrev18 mutant is associated with a complete loss of function of ush and also other genes; it was found to be associated with a deficiency, sequences are deleted from position −4 kb rightward on the map. Mapping of the inversion breakpoint of In(2L)TgR + 1, another null allele of ush (see Materials and Methods) suggested that the ush transcription unit is situated at the position +26 kb (Fig. 5). Furthermore, fragments extending from +16 kb to +35 kb were found to label the embryonic amnioserosa after in situ hybridization, which is known to be affected in ush mutants (P. Heitzler and R. Ray, unpubl.). These DNA sequences were used to probe a Northern blot from embryonic, larval, pupal, and adult stages. A poly(A)+ transcript of ∼4.7 kb was detected with peaks of expression during early embryonic stages, at 4–8 hr, and also in third-instar larvae, pupae, and weakly in adults (data not shown). These fragments were also used to probe an embryonic cDNA library prepared from 4- to 8-hr embryos (see Materials and Methods). From the four cDNAs isolated, we sequenced the longest one (pU4.3) together with the corresponding genomic regions. The deduced structure is shown in Figure 5. To confirm that the transcription unit that we identified corresponds to the ush gene, we performed germ-line transformation with a cosmid clone. The cosmid cos4 contains sequences extending from the breakpoint of ushrev24 (+2 kb) to the end of the transcription unit (+35 kb, see Fig. 5A) and therefore probably spans the entire transcription unit. No other transcription unit were detected. The transformed line obtained with this cosmid inserted on the second chromosome is able to rescue to viability the two lethal mutants ushVX22 and ushTgR + 1, demonstrating that cos4 contains the ush gene. However, the rescued flies show a bristle phenotype similar to the viable mutant ushrev24, indicating that regulatory sequences located further upstream are required for complete wild-type function.

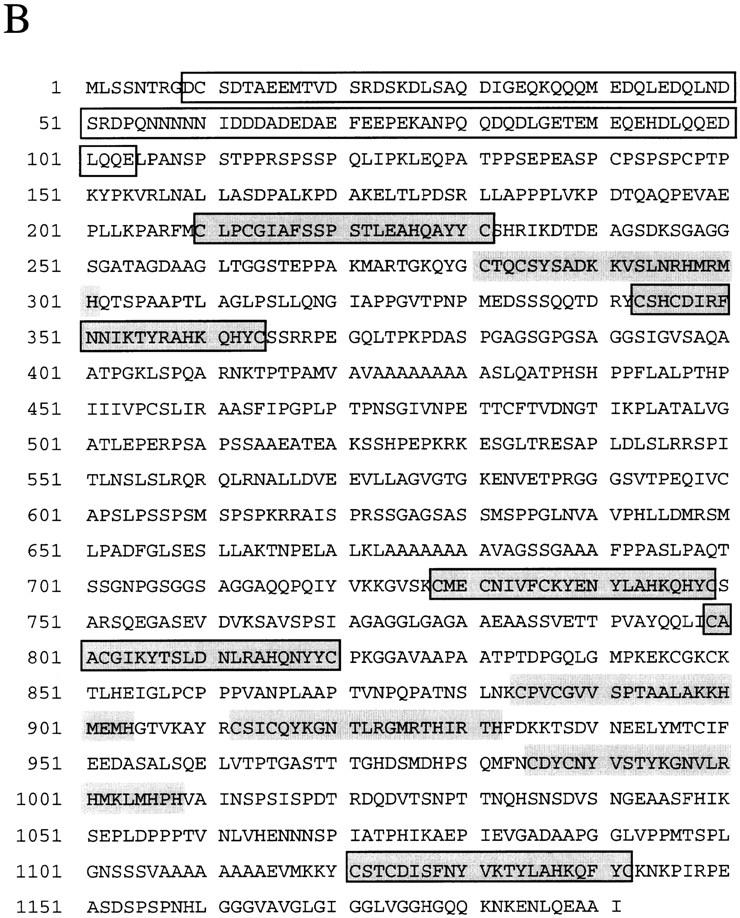

Figure 5.

Structure and protein sequence of the gene ush. (A) Genomic map of the ush region. Proximal is to the right. The localization of some mutant ush alleles corresponding to deletions (ushrev24, ushrev18), to an insertion of a TE element (TE99) and to an insertion of a P element (ush1513) or to an inversion [In(2L)TgR + 1] is shown. Solid bars denote the direction of the deletions and incertitude concerning the precise breakpoint is indicated by hatched boxes. The breakpoint associated with In(2L)TgR + 1 is localized between +24 and +28 kb on the map and is symbolized by a hatched box. The transposon insertion site of ush1513 is shown by an arrow (0 kb on the map). The insertion point of the TE element is localized in the region designed by a hatched box (between −2 and 0 kb on the map). The intron/exon structure seen by comparison between the cDNA and the genomic DNA is indicated. The genomic region included in the cosmid cos4 and located between +2 and +35 kb on the map, allows almost complete rescue of ush null alleles. The restriction sites shown are EcoRI, BamHI, HindIII, NotI, which correspond to E, B, H, and N, respectively. (B) The sequence of the Ush protein corresponding to 1191 amino acids was predicted from both genomic and cDNA pU4.3 clones. The acidic region located in the amino-terminal part of Ush is boxed. Putative zinc fingers of both CCHC and CCHH type motifs are shown in grey, the CCHC ones are also boxed.

ush encodes a large putative zinc finger protein

The sequence of both genomic and cDNA pU4.3 clones revealed a single open reading frame (ORF) coding for 1191 amino acids with a relative molecular mass of 123 kD (Fig. 5B). The Ush ORF displays two types of repeated motifs, CCHH and CCHC, found in several transcription factors of the zinc finger family (Berg 1993). Apart from the typical arrangement of the two cysteines and histidines, no particular consensus is apparent for the CCHH motifs. Nevertheless, the first motif of this type (amino acids 281–301) shows a similarity to the second zinc finger motif of the ZFY transcription factor family (Fig. 6; Ashworth et al. 1989; Mardon et al. 1990; Palmer et al. 1990). The CCHC motifs have been described for several zinc finger containing proteins, but the role of this structure has not been elucidated. Finally, the Ush protein also contains an acidic domain in the amino-terminal part of the protein (amino acids 9–104), and several stretches of alanine residues (amino acids 421–431, 674–683, and 1107–1114). All of these characteristics suggest a role for Ush as a nuclear factor. Immunocytochemical analysis of ush cDNA transfected Cos cells with an antibody against Ush revealed a nuclear localization (data not shown). During embryogenesis, Ush is also localized in the nuclei of the cells in which it is expressed (data not shown). Unfortunately, because of the poor sensitivity of our immunodetection technique, we were unable to confirm this nuclear localization in the wing disc.

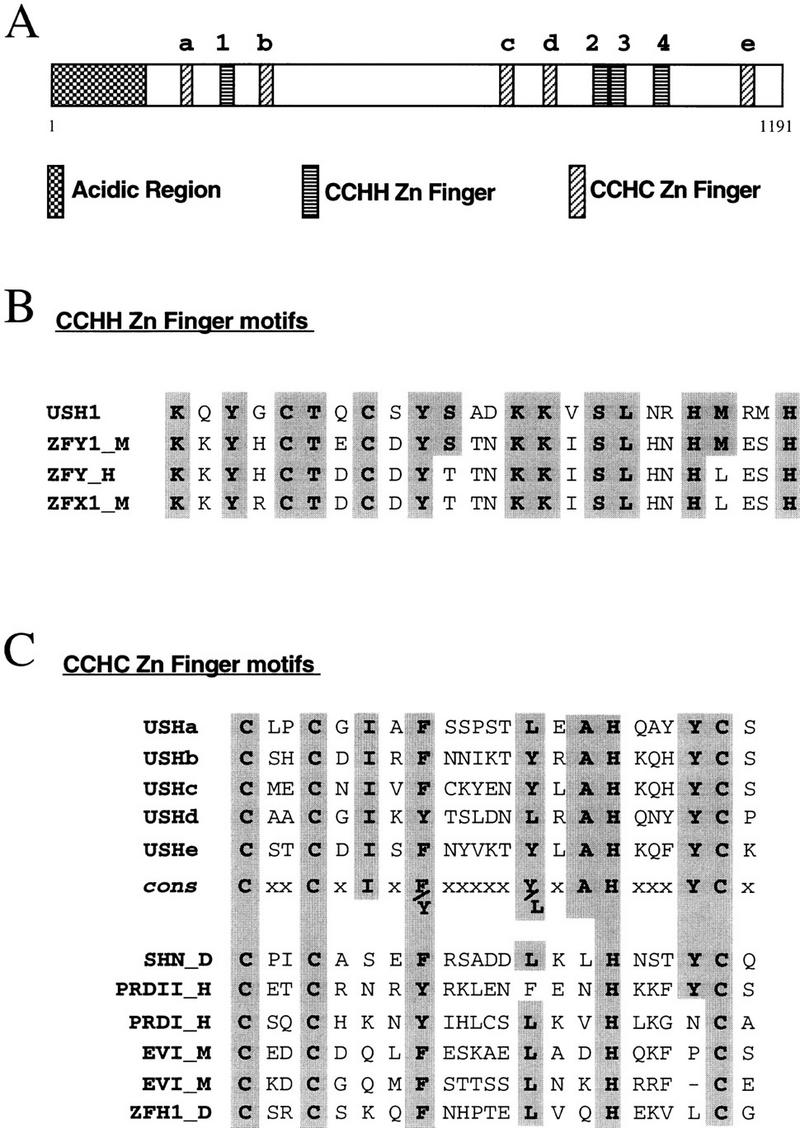

Figure 6.

Structure of the Ush protein and comparisons with several other zinc finger proteins. (A) Location within the Ush protein of the acidic region, and the putative zinc finger motifs, CCHH and CCHC, are represented by different types of boxes. The CCHH and CCHC zinc finger motifs are numbered starting from the N part of the Ush protein, by numbers and letters, respectively. Homologous amino acids are shown in gray. (B) Comparison of the first CCHH zinc finger motif of Ush with the second one of the Zfy zinc finger proteins. The sequences represented correspond to amino acids 277–301 of Ush (USH1); amino acids 433–456 of the murine Zfy-1 (ZFY1_M; Ashworth et al. 1989); amino acids 450–474 of the human Zfy (ZFY_H; Palmer et al. 1990) and amino acids 448–472 of the murine Zfx1 (ZFX1_M; Mardon et al. 1990). (C) Comparison of the CCHC zinc finger motifs of Ush with several zinc finger proteins. cons refers to the consensus sequence presented by the CCHC zinc finger motifs of Ush. The sequences presented correspond to amino acids 210–232; 343–365; 728–750; 799–821; and 1121–1143 of Ush (USHa, USHb, USHc, USHd, and USHe, respectively); amino acids 1063–1085 of the Drosophila Schnurri (SHN_D; Grieder et al. 1995); amino acids 960–982 of the human PRDII-BF1 (PRDII_H; Fan and Maniatis. 1990); amino acids 651–675 of the human PRDI-BF1 (PRDI_H; Keller and Maniatis. 1991); amino acids 23–45 and 219–240 of the murine Evi-1 (Evi_M; Morishita et al. 1988) and amino acids 636–658 of the Drosophila Zfh-1 (ZFH1_D; Fortini et al. 1991). (–) A gap introduced to obtain maximal alignment.

Discussion

The ush gene is required during both embryonic and imaginal development of Drosophila, and encodes a large protein bearing structural zinc finger motifs and an acidic region similar to a number of known transcription factors. No significant homology to known molecules present in the databases was found, but some of the zinc finger motifs of Ush show homologies with several transcription factors. However, as these proteins contain many other zinc finger motifs with no homology to those of Ush, it is difficult to assign a specific function to these motifs. Recently, a protein has been isolated from the mouse that displays an overall structure very similar to Ush (Tsang et al. 1997). This protein, FOG, like Ush, bears an acidic domain located at the amino-terminal part of the protein and nine zinc fingers arranged in two clusters. Interestingly, the protein contains four CCHH and five CCHC motifs, like Ush. Furthermore, a strong homology is found between the CCHC motifs of FOG and Ush that display more than 50% identical amino acids depending on which zinc finger motif is compared (Tsang et al. 1997). Altogether, these data indicate that FOG and Ush, although not homologous, are sufficiently similar to suggest they comprise a new family of zinc finger proteins.

The zinc finger motifs suggest a putative DNA-binding function for the Ush protein. Using immunocytochemistry we were unable to establish the presence of Ush in the nuclei of thoracic disc cells, but a nuclear localization was observed in embryos. On the basis of genetic data ush regulates ac/sc expression via specific enhancer sequences, we have since investigated the possibility that Ush may bind these sequences directly. Gel shift assays with full-length as well as truncated Ush proteins purified from Escherichia coli or from SF9-infected cells with baculovirus did not reveal any binding specificity for the molecule to this putative target sequence. Therefore, Ush may function together with other intermediate factors in the regulation of this potential target sequence.

Our results suggest that ush has three roles in the thoracic imaginal disc, one for the viability of epithelial cells in a restricted area covering the scutellum, one for the dorsal midline closure, and the other for the development of dorsocentral and scutellar bristles in a larger territory, including both the scutellum and the dorsal half of the thorax. ush shows a restricted pattern of expression in the thoracic disc that correlates with those areas of the notum where its function is required. No variations in intensity of expression could be detected, however, that might account for a differential requirement in the scutellum for cell viability. Furthermore, two other areas of ush expression, in the hinge and pleural regions, do not correlate with any apparent visible phenotypes in clones of null alleles covering these territories. Different functions of ush in the different areas of the thorax may depend on other, differentially distributed factors.

In this study, we have concentrated on the function of ush in the development of the macrochaetes, in particular the dorsocentral bristles.

ush regulates ac and sc expression in the dorsocentral region of the notum

Viable hypomorphic loss-of-function alleles of ush display additional dorsocentral bristles. In contrast, overexpression of ush leads to a loss of these same bristles. Our results show that the effects of Ush are mediated through expression of the ac–sc genes. Analysis of double mutants showed that ac and sc act after ush during bristle development. Observations of hypomorphic alleles revealed that the formation of ectopic dorsocentral precursors is a consequence of overexpression of ac–sc in the dorsocentral region. The enhanced ac–sc activity is reflected by the increased expression of ac–lacZ and sca–lacZ. Moreover, this effect is mediated by the dorsocentral enhancer element described by Gomez-Skarmeta et al. (1995), as, lacZ expression driven by these sequences is stronger in mutant ush discs than in the wild type. Consistent with this, overexpression of Ush leads to the loss of the dorsocentral precursor cells and a concurrent loss of ac–sc expression, as well as a loss of the lacZ expression driven by the enhancer sequences. These results are in agreement with a negative role for ush in the regulation of the ac–sc genes at the dorsocentral site.

ush and pnr participate in the same regulatory process

The ush protein is unlikely to regulate the ac–sc genes directly and may function together with other factors. A good candidate to mediate ush function is the product of the gene pnr. A number of observations support this argument. First, a specific genetic interaction exists between a class of pnr mutants, pnrD, and ush mutants that act as dominant enhancers of pnrD. Second, the phenotype of hypomorphic ush mutants are remarkably similar to that of pnrD/+ flies, they display additional dorsocentral and scutellar bristles but a loss of postvertical bristles. Third, both Pnr and Ush regulate ac/sc expression in the dorsocentral proneural cluster and both appear to do so via the dorsocentral enhancer element (Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1995; Haenlin et al., this issue). Taken together, these data suggest that Ush and Pnr function in the same developmental pathway to regulate ac–sc expression at the dorsocentral site. Recent work has revealed that Pnr is a transcriptional activator, that the Ush and Pnr proteins associate with one another, and that the activating function of Pnr is lost when it is associated with Ush (Haenlin et al., this issue). Furthermore the pnrD proteins have a reduced ability to associate with Ush and almost completely resistant to the modulating effects of Ush (Haenlin et al., this issue).

A role for ush in the precise positioning of the dorsocentral bristles

Clones of cells mutant for null alleles in the dorsocentral region, have a mutant phenotype showing that the mutant cells act autonomously. Unexpectedly however, the mutant patches are frequently devoid of bristles. This is in contrast to the hypomorphic alleles, which result in the differentiation of additional bristles. These observations suggest, that, although the amount of ush product is crucial for bristle development, bristles do not arise as a simple consequence of the presence or absence of the Ush protein. Rather, the levels of ush product may be involved in the precise positioning of the bristles. Two observations are relevant to this question. First, it is noteworthy, that in the wild-type disc the dorsocentral precursors arise at the very edge of the domain of detectable ush expression, at a site where expressing and nonexpressing cells are likely to be adjacent (or where the levels of Ush may be reduced). Second, in mosaic thoraces where mutant and wild-type cells are juxtaposed, the bristles are never in the correct positions and the majority of them form precisely along the mosaic border. This observation holds whether the bristles are of the mutant or the wild-type genotype. These observations suggest strongly that bristles form at the edges of a boundary between high and low levels of Ush. We have also observed that under mild heat shock conditions, an increase of ush expression causes the development of additional dorsocentral bristles, at a position that would correspond to the border of the endogenous ush expression domain (data not shown).

There is an additional feature of the mosaics that is of importance. The position of the wild-type bristles is modified by the neighboring mutant cells, that is, the mutant cells have a nonautonomous effect on their wild-type neighbors. Therefore, in the case of the mosaics involving the null mutant clones, the majority of bristles that form are of the wild-type genotype and they are found in altered positions demonstrating that the wild-type cells have been induced to develop bristles at ectopic sites by the presence of neighboring mutant cells. Furthermore, not only do wild-type bristles form at the clone border, they are also displaced a short distance away from the border. The distance separating the marked mutant cells from the wild-type bristles is one, two, or occasionally three epidermal cells. It is of interest that similar observations have been made in mosaics of pnrD mutants (P. Heitzler and P. Simpson, unpubl.). This suggests that in the absence of Ush (or in the presence of the constitutively active PnrD), a diffusible factor may be generated. Therefore, at a border of ush− clones, such a hypothetical factor might diffuse into the neighboring ush+ cells. Interestingly, in mosaics involving hypomorphic alleles, bristles also form at the edge of the mutant clone borders, but in this case the bristles are mainly of the mutant genotype. Production of the postulated diffusible factor may well be stronger in the case of the null mutant clones than for the clones of the hypomorphic alleles. In this context it is of note that the gene wingless, which encodes a diffusible protein, is expressed in a stripe along the notum adjacent to that of ush, and that expression of wingless changes in both pnr and ush mutants (Calleja et al. 1996; Y. Cubadda et al., unpubl.). It has been shown that wingless expression in the notum is required for the normal development of the dorsocentral bristles (Phillips and Whittle 1993). Further studies are required to determine whether the postulated diffusible factor correspond to Wingless.

In conclusion, we suggest that Ush may function to modulate locally the levels of ac–sc to precisely define the position of the precursor. It is known that a group of about six cells in the proneural field express ac–sc to high levels and are competent to make the bristle precursor (Heitzler and Simpson 1991; Cubas and Modolell 1992). The choice of which cell will do so depends in part on lateral signaling mediated by the Notch signaling pathway (Heitzler and Simpson 1991). However, the position of the precursors from the dorsocentral proneural cluster appears to be invariant (Cubas and Modolell 1992), suggesting that specific cells are predetermined to become the SMCs. Local modulation of the Ac–Sc levels could provide a bias. A cell could gain an early advantage by expressing higher levels of ac–sc than its neighbors and therefore be more competitive for the neural fate (Heitzler and Simpson 1991; Heitzler et al. 1996a). Further studies are necessary to determine how Pnr and Ush cooperate in the regulation of ac and sc.

Materials and methods

Fly strains

The locus ush was first defined genetically by the two amorphic mutants ushl(2)19 and ushIIA102 which are lethal at embryonic stages and affect the pattern of the larval cuticle (Nüsslein-Volhard et al. 1984). A large number of mutant alleles have since been isolated and a complete description of the genetics of these will be described elsewhere (P. Heitzler, R.P. Ray, Y. Cubadda, M. Haenlin, L. Seugnet, and P. Simpson, in prep.).

The transposon TE99(Z), located at 21C6 and carrying two adjacent (w+, rst+) units and an internal fold-back sequence (Ising and Block 1981, 1984) was found to be the direct cause of a viable leaky ush mutant phenotype (ushTE99(Z)). The ushSW42 mutant is a spontaneous white (SW) derivative of ushTE99(Z) that exhibits a normal cytology at 21C6, but displays a strong recessive viable adult phenotype. The transposon TE93(R) (Ising and Block 1981, 1984) was used as an ush+ duplication (P. Heitzler, unpubl.).

ush1513 behaves as a hypomorphic allele of ush and carries a P[lacZ, w+] transposon inserted next to the ush gene. Excision of the P[lacZ, w+] resulted in either wild-type ush+ flies, or in a series of ush recessive loss-of-function mutants such as ushrev3, ushrev18, and ushrev24.

ushTgR + 1, ushVX22, and ushE6 correspond to amorphic mutants based on their genetic behavior. They both display the same embryonic phenotype as deletions when homozygous (P. Heitzler, unpubl.). Furthermore, embryos homozygous for ushTgR + 1, ushVX22, or ushE6 show no detectable Ush protein expression using a monoclonal antibody (2us1D5) directed against the ush product.

The pnrD1 mutant is described in Ramain et al. (1993).

The transgenic line B17 (ac–lacZ) harbors 3.8 kb of the ac promotor region fused to the lacZ gene (for details, see Martinez and Modolell 1991).

The transgenic lines DC-3.2 and DC-ac2 harbor the 5.7-kb EcoRI fragment that contains the dorsocentral enhancer fragment fused to 3.7sc–lacZ (3.7 kb of the sc promotor region fused to the lacZ gene) or to 0.8ac–lacZ (0.8 kb of the ac promotor region fused to the lacZ gene) (for details, see Gomez-Skarmeta et al. 1995).

Flies were raised on standard Drosophila medium at 25°C. More than 30 hemithoraces were examined for each of the genetic combinations presented in Figure 1.

Clonal analysis

Mutant clones were produced by hs–FLP/FRT-induced mitotic recombination (Golic and Lindquist 1989; Golic 1991) following procedures described in Heitzler et al. (1996a). Clones were induced in flies of the following genotypes. (1) y FLP1/y; ushVX22 P(y+,ry+)25F ckCH52 FRT40A/P(πM,w+)21C P(πM,w+)36F FRT40A; (2) y FLP1/y; TgR + 1 P(y+,ry+)25F ckCH52 FRT40A/P(πM,w+)21C P(πM,w+)36F FRT40A; (3) y FLP1/y; Df(2L)ushE6 P(y+,ry+)25F ckCH52 FRT40A/P(πM,w+)21C P(πM,w+)36F FRT40A; and (4) yFLP1/y; ushrev24 P(y+,ry+)25F ckCH52 FRT40A/P(πM,w+)21C P(πM,w+)36F FRT40A. The FLP1 and FRT40A inserts are described in Golic (1991) and Xu and Rubin (1993), respectively.

Staining for β-galactosidase activity

Lines S123, A101, and 1513 contain a lacZ gene inserted at the sca (Mlodzik et al. 1990), neuralized (Boulianne et al. 1991), and ush (L. Seugnet and M. Haenlin, unpubl.) loci, respectively. S123 was used to follow expression in the wing imaginal discs of the ac and sc genes (Mlodzik et al. 1990). A101 exhibits staining in all sensory organs precursors (Huang et al. 1991), whereas 1513 shows a staining pattern like that of the endogenous ush gene (data not shown). Selection of mutant or wild-type Oregon R animals at different stages, as well as dissection and treatment of imaginal discs, were performed as described in Ramain et al. (1993). The Gla, Bc, and the TM6B Tb balancers allowed us to recognize the genotype of the larvae, before dissection and staining for β-galactosidase activity.

Molecular cloning

To recover genomic DNA flanking the ush1513 insert, genomic DNA from adult ush1513 flies was extracted (Bender et al. 1983) and 1 μg digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and ligated. Clones bearing genomic DNA flanking the bacterial origin of replication and the ampicillin resistance gene of the P(lacW) were recovered by transformation of E. coli strain XL1-Blue according to the standard transformation protocol of Hanahan (1985). A genomic DNA fragment, flanking the P-element insertion point, was then used as a probe to screen a cosmid library (made by J. Tamkun, University of California, Santa Cruz) and a λ phage EMBL-4 Oregon genomic DNA library (constructed by V. Pirrotta, University of Geneva, Switzerland).

Isolation of ush cDNAs

cDNAs were isolated from a 4 to 8-hr embryonic library (Brown and Kafatos 1988) following the same procedure as the one described in Ramain et al. (1993). The cDNAs were selected through a screen with the 12-kb DNA probes (position +20 to +32 on the map shown in Fig. 5). All cDNAs belong to the same class, with one exception that displayed an artifactual deletion. The longest one, as shown by restriction enzyme mapping as well as in vitro translation using rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega Biotec), was analyzed further.

DNA sequencing

Sequences were obtained using the dideoxy chain termination method as described in Ramain et al. (1993). A cDNA insert of 4.7 kb (KpnI–HindIII fragment) was cloned in pBluescript II SK+ (Stratagene) and directional deletions were generated using the exonuclease III (Stratagene kit). Sequence data were collected for both strands using the M13 universal primer as well as internal synthetic oligonucleotides. The intron/exon structure, as well as the genomic organization of the ush locus, were determined first by hybridization of the cDNA on genomic sequences to localize the exons, and then by sequencing the corresponding genomic fragments using internal synthetic oligonucleotides. A search for homology was performed using the University of Wisconsin GCG software packages (Devereux et al. 1984). In vitro transcription and translation of the cDNA in rabbit reticulocyte lysates and SDS-PAGE analysis revealed a product (Ush) migrating at 200 kD, which confirmed the predicted ORF. Compared with the predicted 123 kD, the difference observed might be attributable to the presence of putative sites for glycosylation in the Ush protein sequence (Hirschberg and Snider 1987).

Expression of ush transcripts in situ

Digoxygenin-labeled DNA was synthesized according to the Boehringer Mannheim protocol and hybridized to imaginal discs using the method of Cubas et al. (1991), modified from Tautz and Pfeifle (1989).

Overexpression of Ush

The cDNA containing the entire ush ORF was subcloned in the plasmid pCaSper–hs (a gift from C.S. Thummel, University of Utah, Salt Lake City) and in pUAST (Brand and Perrimon 1993) using appropriate restriction sites. These plasmids were used to transform embryos of a w1118 stock and homozygous lines were established for the second and third chromosomes. UAS–ush lines were crossed to several lines expressing GAL4, but only crosses with the pnrMD237 Gal4-expressing line (Calleja et al. 1996; Heitzler et al. 1996b) gave viable adult progeny. Early third-instar larvae were subjected throughout two days to a heat treatment regime of 30 min at 37°C followed by 2 hr at 25°C.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cathie Carteret, Serge Vicaire, and Claudine Ackerman for excellent technical assistance; Adrien Staub and Frank Ruffenach for oligonucleotide synthesis; Yves Lutz for making the Ush antibody; Juan Modolell, Marek Modzlik, Ginès Morata, and the Drosophila stock centres at Bowling Green and Umea for mutant strains; and our colleagues at the I.G.B.M.C. for thoughtful discussions throughout the course of this work. We are grateful to Stuart Orkin for sharing unpublished information with us and Juan Modolell and especially Pilar Cubas for their help with the technique of in situ hybridization in imaginal discs. M.H. visited the laboratory of Juan Modolell as a recipient of a short-term European Molecular Biology Organization grant. Our work is supported by INSERM, CNRS, the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Régional, the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, grant no. 92N60/0694 from the Ministère de la Recherche et de l’Éducation; the European Community (contract ERBCHRXCT940692) and the Action Concertées-Sciences du Vivant no. 4 du Ministère de l’Education Nationale de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Note added in proof

The sequence data described in this paper have been submitted to EMBL under accession no. ACY12322.

Footnotes

E-MAIL march@igbmc.u-strasbg.fr; FAX (33) 88 65 32 01.

References

- Ashworth A, Swift S, Affara N. Sequence of cDNA for murine Zfy-1, a candidate for Tdy. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2864. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.7.2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcells L, Modolell J, Ruiz-Gomez M. A unitary basis for different Hairy-wing mutations of Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1988;7:3899–3906. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender W, Spierer P, Hogness DS. Chromosomal walking and jumping to isolate DNA from the Ace and rosy loci and the bithorax complex in Drosophila melanogaster. J Mol Biol. 1983;168:17–33. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JM. Zinc finger proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1993;3:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Boulianne GL, de la Concha A, Campos-Ortega JA, Jan LY, Jan YN. The Drosophila neurogenic gene neuralized encodes a novel protein and is expressed in precursors of larval and adult neurons. EMBO J. 1991;10:2975–2983. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NH, Kafatos FC. Functional cDNA libraries from Drosophila embryos. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:425–437. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calleja M, Moreno E, Pelaz S, Morata G. Visualization of gene expression in living adult Drosophila. Science. 1996;274:252–255. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ortega JA, Jan YN. Genetic and molecular bases of neurogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:399–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.002151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano S, Modolell J. Patterning of the Drosophila nervous system: The achaete-scute gene complex. Trends Genet. 1992;8:202–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90234-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubas P, de Celis JF, Campuzano S, Modolell J. Proneural clusters of achaete-scute expression and the generation of sensory organs in the Drosophila imaginal wing disc. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:996–1008. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubas P, Modolell J. The extramacrochaetae gene provides information for sensory organ patterning. EMBO J. 1992;11:3385–3393. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis HM, Spann DR, Posakony JW. Extramacrochaetae, a negative regulator of sensory organ development in Drosophila, defines a new class of helix-loop-helix proteins. Cell. 1990;61:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90212-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan CM, Maniatis T. A DNA-binding protein containing two widely separated zinc finger motifs that recognize the same DNA sequence. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:29–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortini ME, Lai ZC, Rubin GM. The Drosophila zfh-1 and zfh-2 genes encode novel proteins containing both zinc-finger and homeodomain motifs. Mech Dev. 1991;34:113–122. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(91)90048-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alonso LA, Garcia-Bellido A. Extra-macrochaetae, a trans-acting gene of the achaete-scute complex of Drosophila involved in cell communication. Wilhelm Roux’s Arch Dev Biol. 1988;197:328–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00375952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bellido A. Genetic analysis of the achaete-scute system of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1979;91:491–520. doi: 10.1093/genetics/91.3.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrell J, Modolell J. The Drosophila extramacrochaetae locus, an antagonist of proneural genes that, like these genes, encodes a helix-loop-helix protein. Cell. 1990;61:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghysen A, Dambly-Chaudiere C. From DNA to form: The achaete-scute complex. Genes & Dev. 1988;2:495–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golic KG. Site-specific recombination between homologous chromosomes in Drosophila. Science. 1991;252:958–961. doi: 10.1126/science.2035025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golic KG, Lindquist S. The FLP recombinase of yeast catalyzes site-specific recombination in the Drosophila genome. Cell. 1989;59:499–509. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Skarmeta JL, Rodriguez I, Martinez C, Culi J, Ferres-Marco D, Beamonte D, Modolell J. Cis-regulation of achaete and scute: Shared enhancer-like elements drive their coexpression in proneural clusters of the imaginal discs. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1869–1882. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Skarmeta JL, del Corral RD, de la Calle-Mustienes E, Ferre-Marco D, Modolell J. araucan and caupolican, two members of the novel iroquois complex, encode homeoproteins that control proneural and vein-forming genes. Cell. 1996;85:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez F, Romani S, Cubas P, Modolell J, Campuzano S. Molecular analysis of the asense gene, a member of the achaete-scute complex of Drosophila melanogaster, and its novel role in optic lobe development. EMBO J. 1989;8:3553–3562. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieder NC, Nellen D, Burke R, Basler K, Affolter M. schnurri is required for Drosophila Dpp signaling and encodes a zinc finger protein similar to the mammalian transcription factor PRDII-BF1. Cell. 1995;81:791–800. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90540-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenlin, M., Y. Cubadda, F. Blondeau, P. Heitzler, Y. Lutz, P. Simpson, and P. Ramain. 1997. Transcriptional activity of Pannier is negatively regulated by heterodimerization of the GATA DNA-binding domain with a cofactor encoded by the u-shaped gene of Drosophila. Genes & Dev. (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hanahan D. Techniques for transformation of E. coli. In: Glover DM, editor. DNA cloning, a practical approach. Oxford, UK: IRL Press; 1985. pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- Heitzler P, Simpson P. The choice of cell fate in the epidermis of Drosophila. Cell. 1991;64:1083–1092. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzler P, Bourouis M, Ruel L, Carteret C, Simpson P. Genes of the Enhancer of split and achaete-scute complexes are required for a regulatory loop between Notch and Delta during lateral signalling in Drosophila. Development. 1996a;122:161–171. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitzler P, Haenlin M, Ramain P, Calleja M, Simpson P. A genetic analysis of pannier, a gene necessary for viability of dorsal tissues and bristle positioning in Drosophila. Genetics. 1996b;143:1271–1286. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschberg CB, Snider MD. Topography of glycosylation in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:63–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Dambly-Chaudiere C, Ghysen A. The emergence of sense organs in the wing disc of Drosophila. Development. 1991;111:1087–1095. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.4.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising G, Block K. Derivation-dependent distribution of insertion sites for a Drosophila transposon. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1981;2:527–544. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1981.045.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— A transposon as a cytogenetic marker in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;196:6–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00334085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller AD, Maniatis T. Identification and characterization of a novel repressor of beta-interferon gene expression. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:868–879. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley DL, Zimm G. The genome of Drosophila melanogaster. San Diego, CA: Academic Press Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mardon G, Luoh SW, Simpson EM, Gill G, Brown LG, Page DC. Mouse Zfx protein is similar to Zfy-2: Each contains an acidic activating domain and 13 zinc fingers. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:681–688. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C, Modolell J. Cross-regulatory interactions between the proneural achaete and scute genes of Drosophila. Science. 1991;251:1485–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.1900954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlodzik M, Baker NE, Rubin GM. Isolation and expression of scabrous, a gene regulating neurogenesis in Drosophila. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:1848–1861. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.11.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita K, Parker DS, Mucenski ML, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Ihle JN. Retroviral activation of a novel gene encoding a zinc finger protein in IL-3-dependent myeloid leukemia cell lines. Cell. 1988;54:831–840. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nüsslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E, Kluding H. Mutations affecting the pattern of the larval cuticle in Drosophila melanogaster. Part I. Zygotic loci on the second chromosome. Wilhelm Roux’s Arch Dev Biol. 1984;193:267–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00848156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsako S, Hyer J, Panganiban G, Oliver I, Caudy M. Hairy function as a DNA-binding helix-loop-helix repressor of Drosophila sensory organ formation. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2743–2755. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer MS, Berta P, Sinclair AH, Pym B, Goodfellow PN. Comparison of human ZFY and ZFX transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1990;87:1681–1685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RG, Whittle JR. wingless expression mediates determination of peripheral nervous system elements in late stages of Drosophila wing disc development. Development. 1993;118:427–438. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramain P, Heitzler P, Haenlin M, Simpson P. pannier, a negative regulator of achaete and scute in Drosophila, encodes a zinc finger protein with homology to the vertebrate transcription factor GATA-1. Development. 1993;119:1277–1291. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani S, Campuzano S, Macagno ER, Modolell J. Expression of achaete and scute genes in Drosophila imaginal discs and their function in sensory organ development. Genes & Dev. 1989;3:997–1007. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.7.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Gomez M, Ghysen A. The expression and role of a proneural gene, achaete, in the development of the larval nervous system of Drosophila. EMBO J. 1993;12:1121–1130. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Gomez M, Modolell J. Deletion analysis of the achaete-scute locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genes & Dev. 1987;1:1238–1246. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushlow CA, Hogan A, Pinchin SM, Howe KM, Lardelli M, Ish-Horowicz D. The Drosophila hairy protein acts in both segmentation and bristle patterning and shows homology to N-myc. EMBO J. 1989;8:3095–3103. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson P. Notch and the choice of cell fate in Drosophila neuroepithelium. Trends Genet. 1990;6:343–345. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(90)90260-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeath JB, Carroll SB. Regulation of achaete-scute gene expression and sensory organ pattern formation in the Drosophila wing. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:984–995. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D, Pfeifle C. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma. 1989;98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang AP, Visvader JE, Turner CA, Fujirama Y, Yu C, Weiss MJ, Crossley M, Orkin SH. FOG, a novel multitype zinc finger protein, acts as a cofactor for transcription factor GATA-1 in erythroid and magakaryotic differentiation. Cell. 1997;90:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doren M, Bailey AM, Esnayra J, Ede K, Posakony JW. Negative regulation of proneural gene activity: hairy is a direct transcriptional repressor of achaete. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2729–2742. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doren M, Ellis HM, Posakony JW. The Drosophila extramacrochaetae protein antagonizes sequence-specific DNA binding by daughterless/achaete-scute protein complexes. Development. 1991;113:245–255. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villares R, Cabrera CV. The achaete-scute gene complex of D. melanogaster: Conserved domains in a subset of genes required for neurogenesis and their homology to myc. Cell. 1987;50:415–424. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]