Abstract

Molecular interactions are necessary for proteins to perform their functions. The identification of a putative plasma membrane fatty acid transporter as mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase indicated that that protein must have a fatty acid binding site. Molecular modeling suggests that such a site exists in the form of a 500 Å3 hydrophobic cleft on the surface of the molecule, and identifies specific amino acid residues likely to be important for binding. The modeling and comparison with the cytosolic isoform indicated that two residues (Arg 201, Ala 219) were likely to be important to the structure and function of the binding site. These residues were mutated to determine if they were essential to that function. Expression constructs with wild-type or mutated cDNAs were produced for bacteria and eukaryotic cells. Proteins expressed in E. coli were tested for oleate binding affinity, which was decreased in the mutant proteins. 3T3 fibroblasts were transfected with expression constructs for both normal and mutated forms. Plasma membrane expression was documented by indirect immunofluorescence before [3H]-oleic acid uptake kinetics were assayed. The Vmax for uptake was significantly increased by over-expression of the wild type protein, but changed little after transfection with mutated proteins, despite their presence on the plasma membrane. The hydrophobic cleft in mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase can serve as a fatty acid binding site. Specific residues are essential for normal fatty acid binding, without which fatty acid uptake is compromised. These results confirm the function of this protein as a fatty acid binding protein.

Keywords: fatty acid uptake, mutagenesis, moonlighting protein, transporter, protein structure

INTRODUCTION

Long chain fatty acids (LCFA) serve as metabolic fuels, substrates for production of other molecules such as membrane lipids, and intracellular regulators of gene expression. Many of the LCFA used by cells enter from external sources, and therefore must traverse the plasma membrane. It was long assumed that this occurred solely by simple diffusion. However, when kinetic assays of uptake were performed 1, 2 it became evident that fatty acid uptake included a saturable component, indicating a carrier-mediated mechanism. Since the 1980s many additional studies have shown that LCFA cross cell membranes by both diffusion and facilitated processes 3-7 and that, under most conditions, the latter predominate 3, 7.

The first reported LCFA transporter, plasma membrane fatty acid binding protein (FABPpm), was isolated from rat hepatocyte plasma membranes 8 and subsequently found on the surface of, inter alia, adipocytes 9, cardiac myocytes 10 and jejunal enterocytes 11. Reports of amino acid sequences, peptide mapping, other physicochemical properties and immunologic cross-reactivity indicated, surprisingly, that FABPpm was identical to mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase (mAsp-AT) 12, 13. Their apparent identity implied that a single protein possessed both enzymatic and fatty acid binding activities, which were expressed in two different sub-cellular locations.

Immunofluorescence, immune-electron microscopy, and immuno-precipitation confirmed that many cells have mAsp-AT on their plasma membranes 8, 10, 11, 14, 15. The LCFA binding activity of the protein was readily demonstrable 12, 13, but its underlying structural basis was more difficult to elucidate. As a hydrophilic protein that resides principally within the mitochondrial matrix, mAsp-AT has relatively few of the hydrophobic amino acid residues that would be expected to comprise an LCFA binding site. Accordingly, molecular modeling of its crystal structure was employed to ascertain whether its three-dimensional conformation might create a local environment suitable for LCFA binding. Since there is also a cytosolic isoform (cAsp-AT) with little or no affinity for fatty acids 12, 13, it was useful to compare the amino acid sequences and tertiary structures of the two isoforms. These comparisons offered a roadmap that has yielded both a theoretically based identification and experimental confirmation of the presence of a high affinity LCFA binding site in mAsp-AT, and suggested the importance of this binding site for the protein’s role in cellular LCFA uptake.

RESULTS

Preliminary molecular modeling

Modeling mAsp-AT

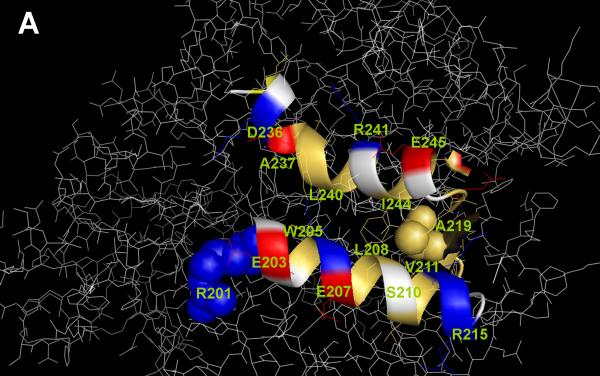

The tertiary structure of chicken heart mAsp-AT was initially evaluated using the molecular modeling program MacroModel16. In this structure, the two principal protein domains (large and small) are closed around the cofactor within the active enzyme catalytic site 17. A hydrophobic cleft was identified between residues 166 and 270, and application of mixed mode Monte Carlo/stochastic dynamics simulation techniques confirmed its characteristics as a putative hydrophobic binding site 18, 19. Its estimated volume, 500 Å3, is similar to those of the LCFA binding sites on albumin (350-500 Å3)20, and to the volume (450-670 Å3) within the larger β-barrel/β-clam LCFA binding sites that are available to hydrophobic ligands in various lipid binding proteins, after allowing for the presence of ordered, hydrogen-bonded water molecules21, 22. Viewed from above (Figure 1A), the cleft resembles an oval depression between α-helices composed of residues 201-215 and 233-246. Arg 201 is situated at the entrance to the cleft and was identified as important for LCFA binding by multiple analytical approaches, while Ala 219 is buried in a strand connecting the two helices. A cross-sectional view (Figure 1B) illustrates the depth of the cleft below the surface of the molecule. Other high resolution crystal structures of chicken heart mAsp-AT 23 incorporating alternate cofactors with or without substrate ligands depict the large and small domains in either an open or closed conformation relative to the cofactor binding site. The hydrophobic cleft is preserved in all cases.

Figure 1.

The tertiary configuration of mAsp-AT. (A) View from above. Two α-helices on the surface of the protein which bound a hydrophobic cleft are enhanced and depicted as a ribbon diagram. The remainder of the protein is rendered in thin white sticks. Residues 201-215 make up the lower of the two helices and residues 233-246 the upper helix in this diagram. Within the helices, hydrophobic (lipophilic) residues are colored in yellow, acids in red and bases in blue. Arg201 (blue), exposed on the surface of the molecule, and Ala219 (yellow), buried beneath the surface, are represented by space-filling van der Waals spheres. Within each of the 2 helices the hydrophobic residues are all found on one face, opposed to the corresponding hydrophobic face of the opposite helix, integral to producing a highly hydrophobic region in the cleft. Image created with PyMOL v0.98 (DeLano, W.L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA, USA). (B) Cross-sectional view. This view illustrates the depth of the cleft in mAsp-AT. A hydrophobic ligand docked within the groove, accessed from the exterior through a narrow slit-like entrance between the solvent-accessible amino acids of the two α-helices, is indicated in white.

Comparison with cAsp-AT

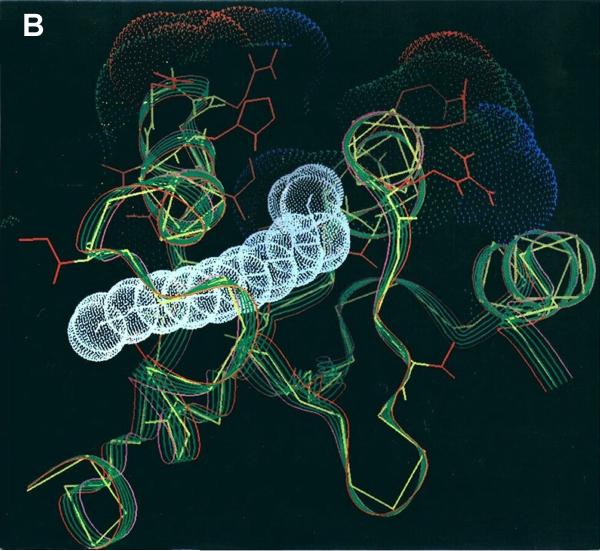

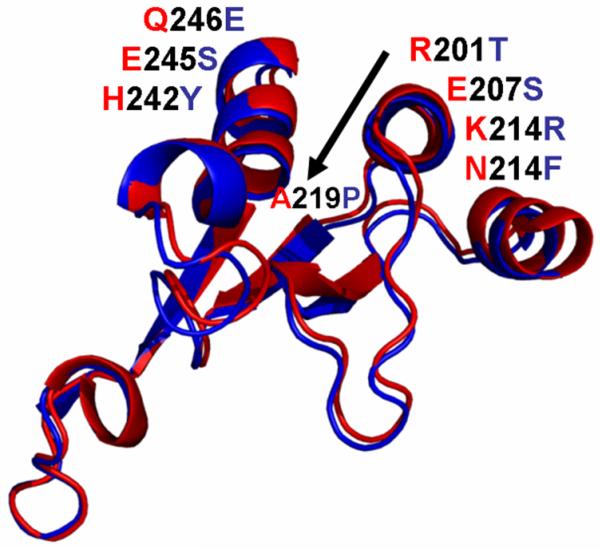

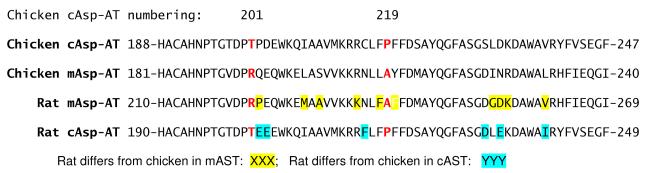

cAsp-AT, a highly conserved enzyme with ~50% homology to mAsp-AT in many species including chicken, rat, and mouse24, catalyzes the same enzymatic reaction, the transamination of aspartate and α-ketoglutarate to glutamate and oxaloacetate. Modeling of its crystal structure (pdb 2cst) indicates that its tertiary configuration is very similar to mAsp-AT, including a virtually identical cleft (Figure 2). However, cAsp-AT does not bind LCFA 12, 13. A cAsp-AT/mAsp-AT protein sequence alignment indicated a degree of homology among the 105 amino acids of the binding site region (residues 166-270), roughly similar to that of the proteins as a whole. The proportion of identical amino acids at cognate sites is approximately 47% for the aligned proteins, and 57% in the binding site region. However, there were 23 residues within the binding site region that are invariant in all known mammalian mAsp-AT’s, and different, but equally invariant, in the corresponding cAsp-AT’s (Table 1). Eight of these represent the replacement in cAsp-AT of residues that are hydrophobic in mAsp-AT either by non-charged polar (n=5) or charged (n=1) amino acids, or the replacement of non-charged polar amino acids by charged, acidic residues (n=2). Twelve of the 23 substitutions, including 6 which alter either hydrophobicity or charge, occur in amino acids 200-216 or 240-250, which define the right and left sides, respectively, of the entrance to the hydrophobic cleft as shown in Figure 2. Four of these changes (two on each side) are in highly exposed residues, including an R201T substitution that eliminates the key positive charge at the terminus of the cleft. Since the binding sites in all LCFA binding proteins studied are reported to consist of long, hydrophobic pockets capped by basic and polar side chains such as arginine or lysine, which form ion pairs with the carboxylate group of a bound LCFA 20-22, 25-27, and our models identify R201 as the residue with the highest affinity for LCFA, this substitution alone might be sufficient to explain the differences in LCFA binding between mAsp-AT and cAsp-AT. However, not all of the significant changes between mAsp-AT and cAsp-AT involve hydrophobicity or charge. ALA 219 in mAsp-AT is deeply buried within a β-strand linking the two sides of the hydrophobic cleft. An A219P substitution in cAsp-AT is predicted to cause a significant local deformation, narrowing the cleft. Thus, the model identifies changes in cAsp-AT that lead not only to a loss of hydrophobicity at critical residues or decrease ionic stabilization of the LCFA terminal carboxyl group, but also those which create steric hindrances to LCFA binding. These findings potentially explain the differences in LCFA binding by these otherwise similar proteins and offer a guide for mapping of the binding site through mutagenesis. Examination of amino acid alignments with sequences from other species 24 indicates that the residues at positions 201 and 219 of both mAsp-AT and cAsp-AT are widely conserved across species, and are identical in the rat to those described above in chicken (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The LCFA binding region of mAsp-AT (pdb-1ama, red) superimposed on the corresponding region of cAsp-AT (pdb-1cst, blue). Viewed in cross section the site appears as a deep fissure between the two helices. The tertiary configurations of the proteins are very similar. However, SACP analysis predicts a binding site centered at position 201 in mAsp-AT (Arg201). Image created with PyMOL v0.98 (see legend to Figure 1A, above).

TABLE 1. Amino acid differences between mitochondrial and cytoplasmic aspartate aminotransferase in the putative fatty acid binding region of chicken heart mAsp-AT.

Throughout the binding site region as a whole, there are 15 hydrophobic amino acids in mAsp-AT compared with 10 in cAsp-AT. In the helices defining the RIGHT and LEFT boundaries of the binding site cleft, the 7 amino acids depicted in bold italic type have a difference in hydrophobicity or charge in cAsp-AT compared to their mAsp-AT counterpart. In 5 of these 7 instances, the change resulted in a relative decrease in hydrophobicity in cAsp-AT compared with mAsp-AT.

| mAsp-AT | cAsp-AT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pos. # | AA | Type | AA | Type | Site | ||

| 166 | CYS | H | ARG | B | |||

| 178 | SER | P | GLU | A | |||

| 180 | ILE | H | ALA | H | |||

| 198 | VAL | H | THR | P | Buried |

|

R

I G H T |

| 201 | ARG | B | THR | P | Exposed | ||

| 207 | GLU | A | GLN | P | Exposed | ||

| 212 | VAL | H | MET | H | Buried | ||

| 214 | LYS | B | ARG | B | Exposed | ||

| 216 | ASN | P | PHE | H | Exposed | ||

| 219 | ALA | H | PRO | H | Buried | ||

| 223 | MET | H | SER | P | Buried | ||

| 242 | HIS | B | TYR | P | Exposed |

|

L

E F T |

| 244 | ILE | H | VAL | H | Buried | ||

| 245 | GLU | A | SER | P | Exposed | ||

| 246 | GLN | P | GLU | A | Exposed | ||

| 248 | ILE | H | PHE | H | Buried | ||

| 250 | VAL | H | LEU | H | Buried | ||

| 252 | LEU | H | CYS | H | |||

| 256 | TYR | H | PHE | H | |||

| 257 | ALA | H | SER | P | |||

| 260 | MET | H | PHE | H | |||

| 264 | GLY | H | ASN | P | |||

| 269 | ALA | H | ASN | P | |||

Type: H = hydrophobic; P = uncharged polar; A = Acidic; B = basic

Figure 3.

Comparison of the amino acid sequence of mitochondrial and cytoplasmic isoforms of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase from rat and chicken. The residues mutated in the study are shown in red. Sequence differences in the isoforms between the two species are highlighted. The numbering system from chicken cAsp-AT is used to align the sequences and in the naming of the mutants for consistency.

Additional modeling strategies

An additional method for detecting interactions of proteins with small ligands, simulation annealing of chemical potential (SACP) 28-30 was applied to study binding between mAsp-AT, cAsp-AT, and model hydrophobic ligands. Using 5 small organic probes, formamide, acetone, methanol, ammonia and methane with water exclusion, SACP predicted two high affinity binding sites on mAsp-AT: the pyridoxal phosphate site and a site at Arg 201 on the diametrically opposite side of the molecule. SACP simulations on cAsp-AT identified the pyridoxal phosphate binding site as the only high affinity site on that protein. To determine the extent of the hydrophobic cavity that was previously found using hydrophobic amino acid analysis, SACP was rerun on mAsp-AT using a hydrophobic probe set: ethane, propane, isobutane, cyclohexane, benzene and toluene. SACP predicted only one high affinity hydrophobic binding domain in mAsp-AT, the cleft from Ala 219 to just below Arg 201. Thus, the complete LCFA binding site appears to encompass both a charged arginine residue and a hydrophobic cleft. The strategy employed by SACP is illustrated in the accompanying Supplemental Material. The theoretical modeling and computational aspects of SACP will be described in detail in a forthcoming review (Guarnieri, F: submitted).

Expression of recombinant proteins

While expression of mAsp-AT in bacterial systems is reportedly difficult 31-33, we successfully expressed recombinant 46 kDa pre-mAsp-AT and its mutants in E .coli, subsequently removing the pre-sequence with trypsin, using a published protocol 31. After isolation and purification, recombinant 43 kDa mAsp-AT was obtained at yields averaging 1 mg/L of culture medium, with an enzyme specific activity averaging 125 IU/mg. This is ~75% of the specific activity of enzyme purified from rat liver 13, 34. We have also isolated the R201T and A219P mutants at similar yields, with specific activities of ~95 IU/mg, and the R201T/A219P double mutant with a specific activity of ~110 IU/mg. Since catalytic activity requires proper folding, the data suggest that these recombinant proteins are substantially folded, which is not always the case with eukaryotic proteins expressed in bacterial systems, and are therefore appropriate to use for studies of relative LCFA binding affinity.

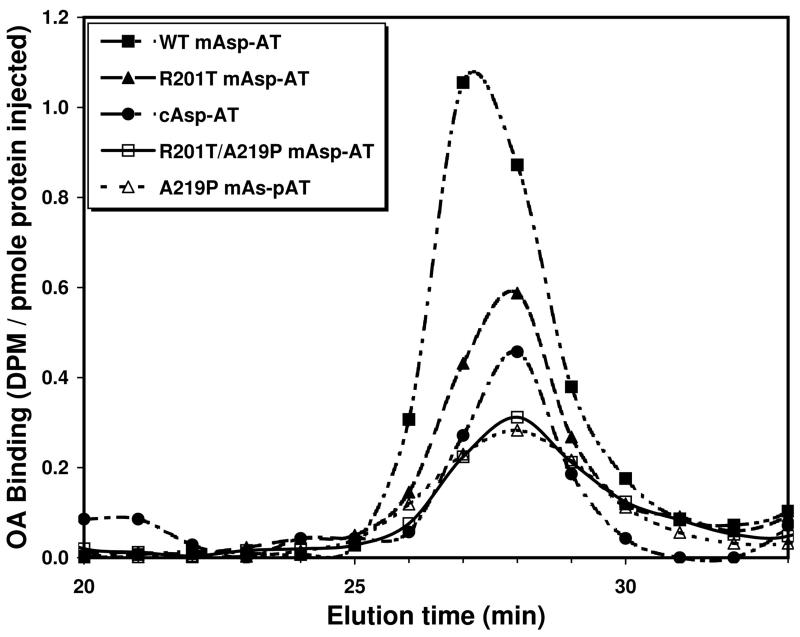

Oleate:mAsp-AT binding

Using formal binding studies we have previously established that oleic acid binds to mAsp-AT at a single site, for which Ka = 1.2-1.4 × 107 M−1 12, 13. In the present study the relative affinity of oleate binding to wild-type mAsp-AT and its binding site mutants was assessed by co-chromatography of [3H]-oleic acid and a protein sample through size exclusion (Superose 12) HPLC columns (Figure 4). Within the absorption peak of a standard quantity of protein, the relative areas under the bound ligand curves (AUCs) provide a measure of relative ligand binding affinity. Graphic estimates of these AUCs, confirmed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), indicate that the LCFA affinity of the R201T mAsp-AT mutant is ~54% of that of the wild type enzyme, those of the A219P and R201T/A219P double mutant were 36% and of cAsp-AT 33%, respectively. The apparent binding to cAsp-AT is non-specific, similar to that seen with other proteins that have no specific fatty acid binding site. The type of interaction responsible for this phenomenon has not been clarified, though it is likely due to either interactions of the carboxyl group with free amino groups or the hydrocarbon chain with aliphatic side chains of the protein. Comparison of the binding curves of [3H]-oleic acid to wild-type mAsp-AT at pH 7.4 and pH 5.5, the pH of acidified endosomes, indicated that the binding of oleic acid to mAsp-AT was reduced by ~80% at pH 5.5.

Figure 4.

HPLC elution curves of [3H]-oleic acid bound to purified mAsp-AT proteins. For each curve oleic acid and protein were incubated for 5 min at an initial oleic acid:protein molar ratio of 1:10. The fractions with bound [3H]-oleate coincide with the protein peaks demonstrated by absorption at 280 nm. Binding of oleic acid to wild-type mAsp-AT is appreciably greater than that to cAsp-AT or to the mutants R201T, A219P and R201T/A219P, indicating that LCFA affinity is reduced if these residues are altered.

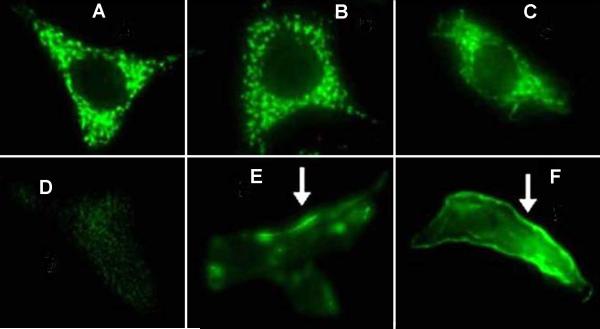

Cell surface expression of transfected mAsp-AT

The sequences of the mutated constructs were confirmed by direct sequencing of the appropriate regions. After transfection of the various clones in pZeoSV2(+) (Invitrogen) into 3T3 fibroblasts, the encoded mAsp-AT proteins were expressed on the cell surface, as evidenced by indirect immunofluorescence studies using monospecific anti-mAsp-AT antibodies. After permeabilization (Figure 5 A-C), all cells showed punctuate fluorescence indicative of the mitochondrial location of the wild-type enzyme. Non-permeabilized control 3T3 cells showed no significant plasma membrane immunofluorescence (Figure 5 D), while those transfected with wild-type mAsp-AT (pZSVAAT) and mutated mAsp-ATs (e.g., pZSVR201T) also showed significant cell surface immunofluorescence (Figure 5 E-F).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescent localization of mAsp-AT in 3T3 cells. In panels A-C cells have been permeabilized, allowing entry of mAsp-AT antibodies and demonstrating abundant mitochondrial localization in each instance. The localization matches that of cells treated with a specific mitochondrial stain (data not shown). In intact, non-permeabilized cells mAsp-AT antibodies do not reach the cell interior and only antigen on the plasma membrane is visualized (D-F). In control 3T3 cells (A and D), only mitochondrial protein is evident, as it is present at a much higher concentration than on the plasma membrane. In cells transfected with wild-type (pZSVAAT, B and E) and mutant (pZSVR201T, C and F) cDNAs, the presence of an increase in mAsp-AT antigens on the cell surface is evident (white arrows). Exposure time for each set (permeabilized or non-permeabilized) was constant to allow for comparison of the different cell lines.

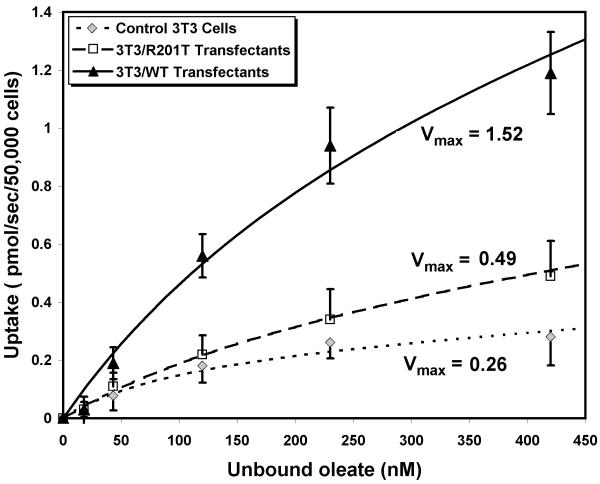

LCFA uptake studies

For comparative studies of protein-mediated LCFA uptake, a change in Vmax has proven to be the most reliable single indicator of a change in uptake 35-41. The Vmax for saturable uptake of [3H]-oleate in control 3T3 cells was 0.26±0.04 pmol/sec/ 50,000 cells (Figure 6) 35. Vmax in cells transfected with the wild-type construct pZSVAAT was increased almost 6-fold (1.52±0.23 pmol/sec/50,000 cells, p<0.025 vs 3T3), whereas Vmax in cells transfected with the mutant pZSVR201T (0.49±0.06 pmol/sec/50,000 cells, p>0.2 vs 3T3) was not significantly increased despite appreciable expression of an immunoreactive mAsp-AT on the cell surface. This suggests that over-expression of mAsp-AT on the cell surface significantly increases LCFA uptake, but only if LCFA binding to the protein is unaltered.

Figure 6.

Oleic acid uptake kinetics in 3T3 fibroblasts and transfectants. Data points represent mean values ± 1 SD for initial [3H]-oleic acid uptake velocities at 5 different unbound oleic acid concentrations, and are derived from three replicate studies. Curves are computer fits of these data to the sum of a saturable and a non-saturable function of the unbound oleic acid concentration, using the SAAM software. The program calculates the Vmax and Km of the saturable component and the rate constant k for non-saturable uptake from the best curve fit for the data. As fatty acids are taken up from the unbound fraction, a minor component compared to the portion bound to albumin, uptake is expressed as a function of unbound oleate concentration. Cells transfected with wild-type mAsp-AT show a significant increase in the Vmax for saturable uptake and in total uptake compared to control 3T3 cells, while uptake in cells transfected with the R201T mutant is not significantly increased.

DISCUSSION

When a protein important for cellular LCFA uptake (FABPpm) proved to be identical to a mitochondrial enzyme (mAsp-AT) 12, 13, it raised the question of how one protein could perform two distinct functions in two separate cellular compartments. Almost simultaneously, other proteins were found to have dual functions, and the term “moonlighting proteins” was coined to describe the phenomenon. The term was first employed by Campbell and Scanes in 1995 42, making mAsp-AT one of the first moonlighting proteins to be recognized, although the term has not been applied to this protein until now. Protein moonlighting has by now been described in plants, fungi, bacteria, and man, and appears to be a widespread phenomena in nature.

Initial reports of the identity of FABPpm and mAsp-AT, suggesting that mAsp-AT might play a role in LCFA transport 12, 13, were met with considerable skepticism, even within our own laboratory. However, the evidence that mAsp-AT reaches the plasma membrane and plays a role in LCFA uptake is by now extensive. Oleic acid binds to mAsp-AT with high affinity (Ka = 1.2-1.4 × 107 M−1) at a single site12, 13. Numerous cell types display mAsp-AT on their cell surfaces 8, 10, 11, 14, 40, 43, and key aspects of its post-mitochondrial trafficking to the plasma membrane and export from the cell via the golgi/endoplasmic reticulum have been elucidated (Berk PD, manuscript in preparation). Its regulated expression strongly correlates with rates of cellular LCFA uptake, especially in adipocytes and hepatocytes 5, 9, 37-41, 44, and transcription rates of the gene and mAsp-AT expression on the plasma membrane parallel LCFA uptake in many experimental settings14, 15, 35, 36, 40. mAsp-AT antibodies not only identify the protein on the plasma membrane, but also selectively inhibit LCFA uptake 5, 9, 10, 14, 15, 35.

Identification of a specific LCFA binding site has now been accomplished by molecular modeling, which first found the hydrophobic cleft, and then identified specific residues critical for LCFA binding, namely Arg 201 and Ala 219. Well studied LCFA binding sites in serum albumin 20, 26, 27, cytosolic fatty acid binding proteins 45-47, and β-lactoglobulin 48, all include long hydrophobic cavities, capped by the positively charged, basic amino acids Arg or Lys that attract the negatively charged carboxylate residues of LCFA electrostatically. Modeling predicted that precisely such a motif also exists within mAsp-AT, and that the R201T substitution would remove the crucial positive charge at the entrance to the binding site, while the A219P mutation would significantly narrow the cleft, resulting in steric hindrance to LCFA entry. Site-directed mutagenesis studies have confirmed these key predictions. Specifically mutated mAsp-ATs had significantly lower affinity for oleic acid than wild type mAsp-AT, associated with a markedly decreased effect on LCFA uptake when over-expressed in 3T3 cells.

Since mAsp-AT does not have the multiple transmembrane domains typical of a plasma membrane transporter, it remains unclear – despite the presence of a high affinity LCFA binding site - precisely how it can function in transmembrane LCFA transport. Preliminary studies from our laboratory suggests that it may participate in an endo-/exocytic recycling process in which it chaperones LCFA import into cells in a manner analogous to the role of transferrin in iron transport 49. Its regulated export from cells, detection on the plasma membrane within coated pits 36 and the loss of LCFA affinity at the pH of acidified endosomes described above are all consistent with this intriguing but unproven hypothesis.

Obesity, the excessive accumulation of LCFA in the form of triglycerides in adipose tissue and other sites, is a major public health issue. Regulation of adipocyte LCFA uptake appears to be a critical control point for body adiposity 50. The probable role of mAsp-AT in fatty acid uptake has been shown in various studies 3, 7, 9, 12-15, 35. In particular, the gene has been shown to be markedly up-regulated in adipose tissue in certain rodent models of obesity 37, 38, and to undergo down-regulation on regimens that promote weight loss51. It is therefore a prime candidate as a molecular cause of increased obesity-associated fatty acid accumulation in adipocytes. If subsequent studies confirm our hypothesis that mAsp-AT plays a major role in adipocyte LCFA uptake, its moonlighting function in fatty acid uptake may prove to be almost as important as its day job as a mitochondrial enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular Modeling

Experimental and computational studies of the binding patterns of small organic molecules to protein often indicate that macromolecules possess highly localized regions of molecular recognition called “Hot-Spots.” 28, 30, 52-55. We used the structure of chicken heart mAsp-AT (pdb 1ama) 17 as the input to simulation annealing of chemical potential (SACP) 28, 29, which uses only structural data about the protein, with no additional input. The principles underlying SACP were described in detail in a recent publication 18, and are illustrated in the accompanying Supplemental Material. Briefly, SACP analysis digitally simulates an experiment in which a model of the protein is immersed in three layers of a specific small molecule ligand, and cavities on or within the protein capable of accommodating a molecule of that size are identified. Each cavity is tested for its potential for the insertion, removal, or rotation of the ligand molecule under given conditions of excess chemical potential. Iterative analysis of each cavity, followed by repetition of the calculations at successively lower levels of excess chemical potential, results in a model in which only those cavities with the greatest affinity for the ligand are occupied, as low affinity sites lead to a high probability of removal. The simulated chemical potential is varied from +10 to −15 in unit increments Six million simulation steps are done at each chemical potential (symbolically represented as B) so that, on average two million attempted insertions, attempted deletions and attempted rotation-translations are performed for each of 25 fixed chemical potentials, for a total of 150,000,000 simulation steps per solvent probe. SACP software is available from Professor Mihaly Mezei, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (inka.mssm.edu/ ~mezei/mmc).

Cloning and Mutagenesis

A rat mAsp-AT cDNA was a gift of Dr. R. Franklin. Clones for rat pre-mAsp-AT in pET3a and pET23a were gifts from Dr. JR Mattingly 56, 57. Mutagenesis of single amino acid residues was performed with the QuickChange Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Two separate clones of rat pre-mAsp-AT cDNA were mutagenized to replace amino acids at positions 201 and 219 (arginine and alanine) with the amino acids found at the equivalent positions in cAsp-AT (threonine and proline), creating R201T and A219P mutant forms of pre- mAsp-AT. The R201T clones were subsequently mutagenized to produce a double mutant, R201T/A219P. The resulting, mutagenized clones were either a standard cDNA in pMAAT2, a plasmid with a metallothionein promoter and ampicillin resistance gene35, or pET23a-AAT-LEH6Y, with a modified C-terminus containing an oligohistidine tract in a vector with a T7 promoter57. The cDNAs from the pMAAT2 mutants were transferred to pZeoSV-2(+) (Invitrogen) by cloning the XbaI - HindIII fragment containing the complete cDNA with ~90 bp of 5′ UTR and >300 bp of 3′ UTR sequence into the NheI and HindIII sites to produce clones with a Zeocin resistance cassette for eukaryotic selection and an SV40 promoter and bovine growth hormone polyA region for eukaryotic expression.

Cell culture

3T3 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s MEM with 10% iron-supplemented calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were transfected with the various cDNAs of interest in pZeoSV-2(+) using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s directions. Selection for stable transfectants was performed by culturing the cells in Hepes-buffered DMEM with serum and antibiotics and 50 μg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen). mAsp-AT isolated from transfectant mitochondria and plasma membranes was exclusively the 43 kDa mature enzyme, indicating that the mitochondrial pre-sequence was excised in these cells.

Immunofluorescence studies

3T3 cells on glass coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in Hank’s BSS (HBSS) for 15 min, washed repeatedly with HBSS, incubated with polyclonal rabbit antisera to mAsp-AT, re-washed, and incubated with FITC-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit IgG. To permeabilize cells to allow antibodies to access the mitochondrial enzyme, 0.1% Triton X-100 was added to the fixative. Viable cells in culture were also treated with antibodies to visualize surface proteins.

Fatty acid uptake studies

Stable transfectants and control 3T3 cells were harvested and [3H]-oleic acid uptake kinetics assessed at 5 different oleic acid:BSA molar ratios (ψ) using the rapid filtration method that is standard in the laboratory15, 35, 36. Uptake data from the 5 studies were plotted as a function of the unbound oleic acid concentration, which was calculated from ψ using the constants of Spector 58. Kinetic constants for saturable and non–saturable uptake were calculated from the data as previously described 3, 7 using the Simulation Analysis and Modeling (SAAM) program 59. Data was fit to a curve described by the equation

where UT(OA) is uptake of oleic acid, [OAu] is the concentration of unbound oleic acid, Vmax and Km are standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics constants and k is the rate of simple diffusion across the membrane, the non-saturable component of uptake.

Briefly, cell suspensions were incubated in 500 μM serum albumin with oleate, including 3H-oleate tracer, at various oleate:BSA ratios for short periods (0 to 30 sec), then washed and solubilized for scintillation counting. Cellular LCFA uptake at five concentrations of oleate was measured in triplicate at five time points, and the counts converted to pmol/sec/50,000 cells. Uptake data was fitted to the sum of a saturable and non-saturable function of the unbound oleic acid concentration using SAAM, which derived the kinetic constants from the fit.

Expression of recombinant proteins in E. coli

Clones with a C-terminal oligohistidine tract were transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3)pLysS (Stratagene), grown in 1 to 3 liter liquid cultures, and induced with IPTG to stimulate T7 polymerase expression, resulting in expression of the particular pre-mAsp-AT encoded by the plasmid 56. After centrifugation, cell pellets were frozen at −20° C. Crude extracts were prepared by suspending the frozen bacteria in 50 mL of sonication buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM 2–oxoglutarate, 1 mM pyridoxal phosphate) containing 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme (Sigma) and 1 U/ml DNase (Worthington) and incubating for 1 hr at room temperature. The suspension was then sonicated on ice until no increase in soluble aminotransferase activity was observed. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation. The soluble fraction was treated briefly with trypsin to remove the pre-sequence 31. It was then loaded on to a ProBond column (Invitrogen) to bind the histidine tagged aminotransferase. Bound aminotransferase was eluted with a step gradient containing increasing concentrations of imidazole. Fractions were assayed for aminotransferase activity and pooled accordingly. Protein content was assayed by the BCA* assay (Pierce). Buffer was exchanged and the protein concentrated using an Amicon stirred-cell ultrafiltration system. Proteins were stored in 100 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.02% NaN3 at pH 7.5. The yield of purified protein averaged ~1 mg/l of culture. Enzymatic activity was assayed with a Sigma kit (AST20).

Oleate Binding Studies

Recombinant proteins produced and purified in the laboratory and cAsp-AT further purified from a commercial sample were incubated with [3H]-oleate and subjected to gel permeation HPLC. Fractions were collected and analyzed by scintillation counting. The elution pattern of the protein was established by UV absorbance at 280 nm. Binding was normalized by converting the data to DPM/pmol protein. Studies on the role of pH in LCFA binding were conducted identically except for altering the pH of the buffer.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by grants DK-26438, DK-52401 and DK-72526 from NIDDK and the Columbia Liver Disease Research Fund. The authors are grateful to Dr. Joseph R. Mattingly, Jr., for vectors and protocols for the successful expression of pre-mAsp-AT and its mutants in E. coli.

Abbreviations

- LCFA

long chain fatty acids

- FABPpm

plasma membrane fatty acid binding protein

- mAsp-AT

mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase

- cAsp-AT

cytoplasmic aspartate aminotransferase

- SACP

simulation annealing of chemical potential

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- HBSS

Hank’s balanced salt solution

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abumrad NA, Perkins RC, Park JH, Park CR. Mechanism of long chain fatty acid permeation in the isolated adipocyte. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:9183–9191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abumrad NA, Park JH, Park CR. Permeation of long-chain fatty acid into adipocytes. Kinetics, specificity, and evidence for involvement of a membrane protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:8945–8953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berk PD, Stump DD. Mechanisms of cellular uptake of long chain free fatty acids. Mol. Cell Biochem. 1999;192:17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stremmel W, Berk PD. Hepatocellular influx of [14C]oleate reflects membrane transport rather than intracellular metabolism or binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1986;83:3086–3090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stremmel W, Strohmeyer G, Berk PD. Hepatocellular uptake of oleate is energy dependent, sodium linked, and inhibited by an antibody to a hepatocyte plasma membrane fatty acid binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1986;83:3584–3588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stump DD, Nunes RM, Sorrentino D, Isola LM, Berk PD. Characteristics of oleate binding to liver plasma membranes and its uptake by isolated hepatocytes. J. Hepatol. 1992;16:304–315. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80661-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stump DD, Fan X, Berk PD. Oleic acid uptake and binding by rat adipocytes define dual pathways for cellular fatty acid uptake. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:509–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stremmel W, Strohmeyer G, Borchard F, Kochwa S, Berk PD. Isolation and partial characterization of a fatty acid binding protein in rat liver plasma membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1985;82:4–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwieterman W, Sorrentino D, Potter BJ, Rand J, Kiang CL, Stump D, Berk PD. Uptake of oleate by isolated rat adipocytes is mediated by a 40-kDa plasma membrane fatty acid binding protein closely related to that in liver and gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988;85:359–363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sorrentino D, Stump D, Potter BJ, Robinson RB, White R, Kiang CL, Berk PD. Oleate uptake by cardiac myocytes is carrier mediated and involves a 40-kD plasma membrane fatty acid binding protein similar to that in liver, adipose tissue, and gut. J. Clin. Invest. 1988;82:928–935. doi: 10.1172/JCI113700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stremmel W, Lotz G, Strohmeyer G, Berk PD. Identification, isolation, and partial characterization of a fatty acid binding protein from rat jejunal microvillous membranes. J. Clin. Invest. 1985;75:1068–1076. doi: 10.1172/JCI111769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berk PD, Wada H, Horio Y, Potter BJ, Sorrentino D, Zhou SL, Isola LM, Stump D, Kiang CL, Thung S. Plasma membrane fatty acid-binding protein and mitochondrial glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase of rat liver are related. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:3484–3488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stump DD, Zhou SL, Berk PD. Comparison of plasma membrane FABP and mitochondrial isoform of aspartate aminotransferase from rat liver. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:G894–G902. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.265.5.G894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou SL, Stump D, Sorrentino D, Potter BJ, Berk PD. Adipocyte differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells involves augmented expression of a 43-kDa plasma membrane fatty acid-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:14456–14461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou SL, Stump D, Kiang CL, Isola LM, Berk PD. Mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase expressed on the surface of 3T3-L1 adipocytes mediates saturable fatty acid uptake. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1995;208:263–270. doi: 10.3181/00379727-208-43854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohamadi F, Richards NGJ, Guida WC. MacroModel - an integrated software system for modeling organic and bioorganic molecules using molecular mechanics. J. Comp. Chem. 1990;11:440–467. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McPhalen CA, Vincent MG, Picot D, Jansonius JN, Lesk AM, Chothia C. Domain closure in mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;227:197–213. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90691-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark M, Guarnieri F, Shkurko I, Wiseman J. Grand canonical Monte Carlo simulation of ligand-protein binding. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006;46:231–242. doi: 10.1021/ci050268f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guarnieri F, Still WC. A rapidly convergent simulation method: Mixed Monte Carlo/stochastic dynamics. J. Comput. Chem. 1994;15:1302–1310. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter DC, Ho JX. Structure of serum albumin. Adv. Protein Chem. 1994;45:153–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banaszak L, Winter N, Xu Z, Bernlohr DA, Cowan S, Jones TA. Lipid-binding proteins: a family of fatty acid and retinoid transport proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 1994;45:89–151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60639-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veerkamp JH, Peeters RA, Maatman RG. Structural and functional features of different types of cytoplasmic fatty acid-binding proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1081:1–24. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(91)90244-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McPhalen CA, Vincent MG, Jansonius JN. X-ray structure refinement and comparison of three forms of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;225:495–517. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90935-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winefield CS, Farnden KJ, Reynolds PH, Marshall CJ. Evolutionary analysis of aspartate aminotransferases. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;40:455–463. doi: 10.1007/BF00164031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaLonde JM, Levenson MA, Roe JJ, Bernlohr DA, Banaszak LJ. Adipocyte lipid-binding protein complexed with arachidonic acid. Titration calorimetry and X-ray crystallographic studies. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:25339–25347. doi: 10.2210/pdb1adl/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattacharya AA, Grune T, Curry S. Crystallographic analysis reveals common modes of binding of medium and long-chain fatty acids to human serum albumin. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;303:721–732. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curry S, Brick P, Franks NP. Fatty acid binding to human serum albumin: new insights from crystallographic studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1441:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vajda S, Guarnieri F. Characterization of protein-ligand interaction sites using experimental and computational methods. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2006;9:354–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guarnieri F, Mezei M. Simulation annealing of chemical potentials: A general procedure for locating bound waters. Application to the study of differential hydration propensities of the major and minor grooves of DNA. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8493–8494. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kulp JL, III, Kulp JL, Jr., Pompliano DL, Guarnieri F. Diverse Fragment Clustering and Water Exclusion Identify Protein Hot Spots. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2011 doi: 10.1021/ja203929x. dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja203929x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mattingly JR, Jr., Youssef J, Iriarte A, Martinez-Carrion M. Protein folding in a cell-free translation system. The fate of the precursor to mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:3925–3937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fluckiger J, Christen P. Degradation of the precursor of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase in chicken embryo fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:4131–4138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lain B, Iriarte A, Martinez-Carrion M. Dependence of the folding and import of the precursor to mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase on the nature of the cell-free translation system. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:15588–15596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stump DD, Zhou SL, Potter BJ, Berk PD. Purification of rat liver mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase and separation of its isoforms utilizing high-performance liquid chromatography. Protein Expr. Purif. 1990;1:49–53. doi: 10.1016/1046-5928(90)90045-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isola LM, Zhou SL, Kiang CL, Stump DD, Bradbury MW, Berk PD. 3T3 fibroblasts transfected with a cDNA for mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase express plasma membrane fatty acid-binding protein and saturable fatty acid uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:9866–9870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou SL, Gordon RE, Bradbury M, Stump D, Kiang CL, Berk PD. Ethanol up-regulates fatty acid uptake and plasma membrane expression and export of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase in HepG2 cells. Hepatology. 1998;27:1064–1074. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berk PD, Zhou SL, Kiang CL, Stump D, Bradbury M, Isola LM. Uptake of long chain free fatty acids is selectively up-regulated in adipocytes of Zucker rats with genetic obesity and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:8830–8835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berk PD, Zhou S, Kiang C, Stump DD, Fan X, Bradbury MW. Selective up-regulation of fatty acid uptake by adipocytes characterizes both genetic and diet-induced obesity in rodents. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:28626–28631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petrescu O, Fan X, Gentileschi P, Hossain S, Bradbury M, Gagner M, Berk PD. Long-chain fatty acid uptake is upregulated in omental adipocytes from patients undergoing bariatric surgery for obesity. Int. J. Obes. Relat Metab Disord. 2005;29:196–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou SL, Stump D, Isola L, Berk PD. Constitutive expression of a saturable transport system for non-esterified fatty acids in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biochem. J. 1994;297(Pt 2):315–319. doi: 10.1042/bj2970315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petrescu O, Cheema AF, Fan X, Bradbury MW, Berk PD. Differences in adipocyte long chain fatty acid uptake in Osborne-Mendel and S5B/Pl rats in response to high-fat diets. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2008;32:853–862. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell RM, Scanes CG. Endocrine peptides ’moonlighting’ as immune modulators: roles for somatostatin and GH-releasing factor. J. Endocrinol. 1995;147:383–396. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1470383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cechetto JD, Sadacharan SK, Berk PD, Gupta RS. Immunogold localization of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase in mitochondria and on the cell surface in normal rat tissues. Histol. Histopathol. 2002;17:353–364. doi: 10.14670/HH-17.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ge F, Zhou S, Hu C, Lobdell H, Berk PD. Insulin- and leptin-regulated fatty acid uptake plays a key causal role in hepatic steatosis in mice with intact leptin signaling but not in ob/ob or db/db mice. Am. J. Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G855–G866. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00434.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hertzel AV, Bernlohr DA. The mammalian fatty acid-binding protein multigene family: molecular and genetic insights into function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;11:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richieri GV, Ogata RT, Zimmerman AW, Veerkamp JH, Kleinfeld AM. Fatty acid binding proteins from different tissues show distinct patterns of fatty acid interactions. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7197–7204. doi: 10.1021/bi000314z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson J, Winter N, Terwey D, Bratt J, Banaszak L. The crystal structure of the liver fatty acid-binding protein. A complex with two bound oleates. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:7140–7150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu SY, Perez MD, Puyol P, Sawyer L. beta-lactoglobulin binds palmitate within its central cavity. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:170–174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nunes RM, BELOQUI O, Potter BJ, BERK BD. Evidence for Receptor-mediated Uptake of Transferrin Iron by Rat Hepatocytes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1986;463:327–329. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berk PD. Regulatable fatty acid transport mechanisms are central to the pathophysiology of obesity, fatty liver, and metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2008;48:1362–1376. doi: 10.1002/hep.22632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan X, Bradbury MW, Berk PD. Leptin and insulin modulate nutrient partitioning and weight loss in ob/ob mice through regulation of long-chain fatty acid uptake by adipocytes. J. Nutr. 2003;133:2707–2715. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.9.2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Landon MR, Lancia DR, Jr., Yu J, Thiel SC, Vajda S. Identification of hot spots within druggable binding regions by computational solvent mapping of proteins. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:1231–1240. doi: 10.1021/jm061134b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mattos C, Ringe D. Locating and characterizing binding sites on proteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996;14:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt0596-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moore WR., Jr. Maximizing discovery efficiency with a computationally driven fragment approach. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2005;8:355–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ringe D, Mattos C. Analysis of the binding surfaces of proteins. Med. Res. Rev. 1999;19:321–331. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199907)19:4<321::aid-med5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Altieri F, Mattingly JR, Jr., Rodriguez-Berrocal FJ, Youssef J, Iriarte A, Wu TH, Martinez-Carrion M. Isolation and properties of a liver mitochondrial precursor protein to aspartate aminotransferase expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:4782–4786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mattingly JR, Jr., Torella C, Iriarte A, Martinez-Carrion M. Conformation of aspartate aminotransferase isozymes folding under different conditions probed by limited proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23191–23202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spector AA, Fletcher JE, Ashbrook JD. Analysis of long-chain free fatty acid binding to bovine serum albumin by determination of stepwise equilibrium constants. Biochemistry. 1971;10:3229–3232. doi: 10.1021/bi00793a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berman M, Weiss MF. Users’ Manual for SAAM. US Government Printing Office; Washington DC: 1967. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.