Abstract

Although neuroimaging has long played a role in the acute management of pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI), until recently, its use as a tool for understanding and predicting long-term brain-behavior relationships after TBI has been limited by the relatively poor sensitivity of routine clinical imaging for detecting diffuse axonal injury (DAI). Newer magnetic resonance-based imaging techniques demonstrate improved sensitivity to DAI. Early research suggests that these techniques hold promise for identifying imaging predictors and correlates of chronic function, both globally and within specific neuropsychological domains. In this review, we describe the principles of new, advanced imaging techniques including diffusion weighted and diffusion tensor imaging, susceptibility weighted imaging, and 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In addition, we summarize current research demonstrating their early success in establishing relationships between imaging measures and functional outcomes after TBI. With the ongoing research, these imaging techniques may allow earlier identification of possible chronic sequelae of tissue injury for each child with TBI, thereby facilitating efficacy and efficiency in delivering successful rehabilitation services.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, child, imaging, MRI

Neuroimaging after traumatic brain injury (TBI) classically serves a crucial role in identifying acute and chronic sequelae of injury, such as intracranial hematomas, brain contusions, and posttraumatic complications including hydrocephalus and infections. These imaging results often guide acute and chronic medical or surgical intervention [Lee and Newberg, 2005]. However, until recently, neuroimaging was limited in predicting long-term outcomes after TBI. This is due, in part, to the relative insensitivity of conventional, anatomical imaging modalities to microstructural injuries like diffuse axonal injury (DAI). In the past decade, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become widely available. The high spatial resolution, high signal and contrast to noise ratio, and the different tissue contrasts that can be generated by MRI significantly increased the diagnostic accuracy of neuroimaging in identifying early and chronic sequelae of TBI. Moreover, a number of advanced MRI techniques that study microstructural injuries, including diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI), became available. These recent MRI techniques have demonstrated an increased sensitivity to DAI. As a result, a body of literature has emerged identifying imaging-based biomarkers of tissue injury and predictors of functional outcome after pediatric TBI. The ability to identify the exact extent and quality of brain injury as early as possible after TBI may help to predict the likely long-term sequelae of injury for a particular child and allow tailoring and monitoring of therapy. Time-sensitive interventions could be initiated immediately to limit primary and secondary brain injury. In addition, early intervention could be provided with pharmacological or behavioral treatments for specific neurocognitive sequelae. Early identification and estimation of likely functional outcome would allow planning for and timely use of valuable resources to optimize home, school, and community reentry. Together, earlier, targeted interventions would likely lead to improved functional outcomes for the individual as well as greater efficiency in the design and delivery of rehabilitation services.

We limited our review/discussion of the current literature on TBI imaging findings and functional outcomes, wherever possible, to studies focused on the pediatric population. Age-related differences in body anatomy and characteristics, child-specific activity patterns, and the progressing maturation of the pediatric brain and skull compared to that of the adult have a significant impact on the observed injury patterns in TBI. For example, the thinner skull and open sutures and higher water content, progressing myelination, and higher sensitivity to oxidative stress of the pediatric brain contribute to differences in injury and recovery patterns observed in children when compared with adults following TBI [Bauer and Fritz, 2004]. Furthermore, the identical injury to a maturing brain compared to an adult brain is likely to result in differing long-term outcomes. There is evidence that the higher degree of brain plasticity and functional reorganization observed in young children is beneficial following a focal brain injury but that diffuse brain injury in younger children results in worse outcomes; it may be that injury during the process of myelination disrupts the development of networks mediating higher order cognitive functions [Taylor and Alden, 1997; Levin, 2003].

In this article, we review the classical, anatomical imaging modalities and sequences typically used in clinical practice followed by a discussion of more advanced imaging techniques that progressively emerge from research protocols into routine clinical protocols.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

Clinically, computed tomography (CT) is ideally suited for acute imaging of children who suffered TBI. CT is widely available, easy to perform, renders high quality images in a short acquisition time, and is highly sensitive in detecting conditions that require emergent attention such as large space occupying hematomas with secondary ascending or descending brain herniation. In addition, children are easily accessible to the emergency physicians during scanning. Moreover, CT gives both information about the brain as well as the skull, and frequently head CT is combined with a cervical spine CT to rule out spine injury, especially when the history of trauma is unclear. The value of CT in the acute setting of TBI is firmly established. In children, more recent studies of CT findings in TBI have largely been focused on identifying imaging findings which discriminate accidental from non-accidental injury in young children; on follow-up, children with accidental injuries have demonstrated better outcomes compared with children with nonaccidental head injury [Ewing-Cobbs et al., 1998]. CT findings found to be suggestive of nonaccidental injury include combinations of chronic and acute injury, e.g., atrophy, ex vacuo dilatation of ventricles, subdural hygromas, subdural hematoma, and multiple acute and chronic extra-axial hematomas [Ewing-Cobbs et al., 1998, 2000; Keenan et al., 2004]. In contrast, skull fractures, intra-parenchymal hematomas, and epidural hematomas have been found to be more common in accidental TBI [Ewing-Cobbs et al., 2000; Keenan et al., 2004]. However, any time that the mechanism of trauma does not explain the encountered imaging findings, nonaccidental injury should be ruled out.

In adults with TBI, Englander et al. [2003] found that presence of midline shift greater than 5 mm or subcortical contusions identified on head CT in the first week after TBI was associated with a greater need for assistance and/or supervision both at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and at 1 year follow-up. Sherer et al. [2006] used a standardized, quantitative analysis approach for evaluating acute CT findings and correlated these measures with neuropsychological function during inpatient rehabilitation. They concluded that a standardized imaging analysis method did not improve upon the use of demographic factors and time to follow commands with regard to predicting early cognitive outcome.

Although CT provides important information in the acute setting, it is limited in identifying the exact extent of DAI, and in the acute setting, CT will visualize only the most obvious findings. Additionally, the use of ionizing radiation involved in CT scanning limits its practicality for use in longitudinal studies of children. The need for a nonionizing imaging modality with a higher sensitivity for subtle, diffuse injuries is straightforward. MRI seems to be ideally suited due to the lack of ionizing radiation, the multiplanar capability, the high spatial resolution, the excellent contrast to noise and signal-to-noise ratio, and the multiple tissue contrasts that can be generated.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Multiple studies have shown the higher sensitivity of MRI compared to CT for identifying DAI [e.g., Gentry et al., 1988; Lee et al., 2008]. Multiple studies are available comparing imaging findings using conventional MRI sequences with global functional outcome as well as more specific neuropsychological and psychiatric outcomes. The studied MR sequences include T1-and T2-weighted spin-echo or fast spin-echo sequences, fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (which has demonstrated increased sensitivity to DAI compared with T2-weighted images [Ashikaga et al., 1997]), and T2★-weighted gradient echo sequences.

Two groups have identified a relationship between the anatomical location of lesions and global function after pediatric TBI. A centrally located lesion, within the basal ganglia or brainstem, is associated with poorer outcome. Levin et al. [1997] found a relationship between depth of lesion and outcome in children imaged in either the subacute (at least 3 months after injury) or chronic (more than 3 years after injury) phase of TBI. Grados et al. [2001] examined images obtained 3 months after TBI and found that depth of lesion correlated with child’s outcome both at discharge from inpatient rehabilitation and at 1 year follow-up. In both cases, deeper, or more centrally located, lesions were associated with worse outcomes.

With regard to specific outcomes, studies have reported several specific MRI findings to be correlated with neuropsychological and psychiatric outcomes. Power et al. [2007] identified that the severity of lesions outside of the frontal lobes (extrafrontal lesions) and combined frontal and extrafrontal lesions 5 years after TBI were predictive of attentional function, whereas the severity of isolated frontal lesions were not predictive of attentional function. Similarly, Salorio et al. [2005] found that total lesion volume outside the frontal and/or temporal lobes, as identified on MRI examinations acquired 3 months after injury, was predictive of memory function 1 year after TBI. The total lesion volume added predictive value beyond that provided by initial clinical measures of severity of injury and the volume of frontal/temporal contusions. Slomine et al. [2002] found, in an overlapping cohort, that volume of extrafrontal lesions and total number of lesions were predictive of domains of executive functioning at 1 year postinjury, though frontal lesion volume was not predictive of performance on measures of executive function. As with the studies examining the role of central lesion location, these findings suggest that the global burden of DAI may be more important than localized injury with regard to predicting outcomes.

Anatomic MRI predictors of posttraumatic attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), personality change disorder, anxiety disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorders have also been investigated. Herskovits et al. [1999] reported an association between lesions within the right putamen detected 3 months after TBI and diagnosis of secondary ADHD 1 year after TBI. In an overlapping cohort, Gerring et al. [2000] found that for children with thalamus and/or basal ganglia injury, the odds of developing secondary ADHD were three times higher than among children without injuries identified in those regions. In contrast, other groups have not found associations between number and/or location of injury and development of features of secondary ADHD [Leblanc et al., 2005; Max et al., 2005]. With regard to personality change disorder, Max et al. [2006] reported that the presence of injuries to the superior frontal gyrus detected on MRI 3 months after TBI was predictive of the presence of personality change disorder between 6 and 12 months. In contrast, frontal white matter injury predicted the presence of personality change between 12 and 24 months after TBI. Grados et al. [2008] found that the presence of mesial pre-frontal and temporal lobe lesions was associated with new-onset obsessions after childhood TBI, whereas Vasa et al. [2004] reported that injury to the orbitofrontal cortex is associated with a decreased risk for postinjury anxiety. Lack of consensus within the literature may, in part, be due to the relative insensitivity of conventional, anatomical MRI sequences to DAI.

In addition to lesion-based analyses, morphological analyses have been performed using conventional MRI sequences to detect diffuse and localized atrophy following pediatric TBI and to investigate the relationship of atrophy to functional outcome. Higher degrees of cerebral atrophy following pediatric TBI have been shown to be associated with worse global outcomes [Wilde et al., 2005]. With regard to specific neurocognitive outcomes after TBI, whole brain volume loss has been shown to correlate with cognitive intelligence deficits [Hopkins et al., 2005], hippocampus volume loss with memory deficits [Hopkins et al., 2005], and corpus callosum volume loss with processing speed deficits [Verger et al., 2001].

DIFFUSION WEIGHTED IMAGING

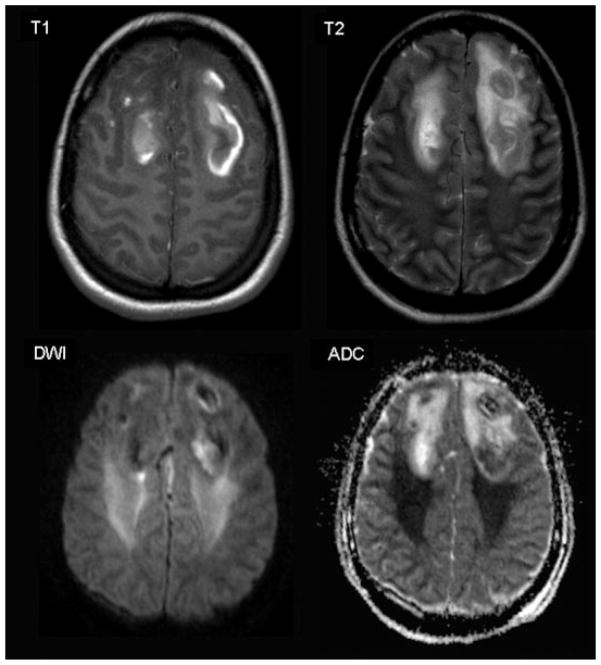

DWI is a recent, noninvasive functional MRI development. DWI relies on differences in diffusion/mobility of protons within the brain. Dedicated imaging sequences generate DWI-weighted images as well as calculated maps of the spatial distribution of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) within the brain. Areas with a high degree of diffusion, such as the cerebro-spinal fluid, will be hypointense on diffusion weighted images and display a high ADC value. Areas with restricted diffusion, e.g., protons within the gray and white matter, will be hyperintense on diffusion weighted images and display a low ADC value. This technique allows differentiation between cytotoxic edema (restricted diffusion) and vasogenic edema (increased diffusion) [Warach et al., 1995; Gass et al., 2001; Huisman, 2003]; cytotoxic and vasogenic edema have both been noted in association with DAI [Huisman et al., 2003]. Vasogenic edema results from a leakage of water from the vessels into the extracellular space, while cytotoxic edema results from a shift of water from the extracellular space into the intracellular space, frequently due to local ischemic and/or hypoxic phenomena [Huisman, 2003]. The identification of vasogenic versus cytotoxic edema may be predictive of outcome because vasogenic edema may be reversible, especially if adequate treatment is initiated, while cytotoxic edema is most frequently irreversible. Figure 1 demonstrates DWI findings after TBI.

Fig. 1.

Axial MR images from a 16-year-old female 8 days after severe TBI. T1- and T2-weighted images demonstrate bilateral hemorrhagic frontal lobe contusions. DWI and derived ADC image demonstrate vasogenic edema (hypointense on DWI and hyperintense on ADC map) in the region of the contusions as well as cytotoxic edema (hyperintense on DWI and hypointense on ADC map). Cytotoxic edema suggests ischemic and/or hypoxic injury extending beyond the region of injury identified on T1- and T2-weighted sequences.

Recently, Galloway et al. [2008] investigated the value of DWI in children with TBI in relationship to clinical outcomes. DWI revealed a greater extent and degree of abnormality than T2-weighted and FLAIR images, and the measured ADC values of the white matter were lower in patients with more severe injuries. Average total brain ADC, calculated from a number of gray and white matter regions without obvious TBI on T2-weighted images, predicted dichotomous (good versus poor) clinical outcome at 6–12 months after TBI in 83% of the children. Patrick et al. [2007] studied the combined MRI findings (DWI, T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and FLAIR images) associated with ongoing presence of a “low-response” state (Rancho Los Amigos levels 1–3) at 30 days after TBI in comparison to children who had emerged from a low response state by 30 days postinjury. They concluded that brainstem injuries, especially those associated with basal ganglia and thalamus injuries, were strongly associated with persisting low response state.

DIFFUSION TENSOR IMAGING

DTI is a further development of DWI, which allows measurement of the directionality of diffusion as well as the proportion of isotropic and anisotropic diffusion within the brain. The rate and three-dimensional distribution/direction of diffusion of water molecules within the brain are determined by the microstructural architecture of the brain. Isotropic diffusion means that the diffusion is equal in all directions, like that in the cerebrospinal fluid. Anisotropic diffusion means that diffusion is restricted in one direction while enhanced in another direction; this is observed along fiber tracts, where the diffusion is restricted perpendicular to the main axis of the fiber tract, due to the myelin sheath, and enhanced along the main axis of the fiber tract. The more compact the microstructure of the fiber tract, the higher the degree of anisotropic diffusion. The degree of anisotropic diffusion is correlated with the integrity of the fiber tracts and can be calculated by adapting the diffusion sequence. DTI applies diffusion gradients along at least six different anatomical directions in space and consequently allows representation of the degree of anisotropic diffusion throughout calculation of the fractional anisotropy (FA) index. This FA index ranges between 0 and 1. FA of 0 represents complete isotropic diffusion, as in the cerebrospinal fluid, while FA of 1 represents maximal anisotropic diffusion, as seen along tightly packed fiber tracts. In DAI fiber tracts may be injured and disrupted, which will result in a reduction of the FA value. DTI measures of anisotropy are more sensitive than routine MRI for evaluating white matter injury after TBI [Arfanakis et al., 2002], and FA value has been shown to correlate with initial Glasgow Coma Scale score and outcome scores in patients with TBI. Consequently, FA analysis may be a valuable noninvasive biomarker of tissue injury for use in predicting outcomes [Huisman et al., 2004]. Multiple groups have demonstrated reductions in FA in the chronic phase of mild, moderate, and severe pediatric TBI [Wilde et al., 2006; Wozniak et al., 2007; Yuan et al., 2007]. Recently, Wilde et al. [2008] published evidence that FA is increased acutely (within 1 week) after mild pediatric TBI, likely representing transient cytotoxic edema.

Multiple studies provide support for an association between FA and injury severity or functional outcome after pediatric TBI. Yuan et al. [2007] demonstrated in children at least 1 year after TBI that FA across a number of white matter tracts correlates with initial rating of severity of TBI, while in a cohort including adolescents through adults (ages 11–57), total white matter mean FA correlated with clinical markers of severity of TBI [Benson et al., 2007]. Levin et al. [2008] have also demonstrated a relationship between a composite FA score obtained 3 months after injury and both clinical severity of injury and concurrent global as well as specific cognitive outcomes. Further support for the relationship between FA and specific chronic cognitive outcomes comes from studies of children demonstrating correlation between regional FA in frontal and “supracallosal” areas and measures of executive functioning and motor speed [Wozniak et al., 2007] and correlation between corpus callosum FA and processing speed [Wilde et al., 2006].

Two recent studies have reported longitudinal changes in FA following moderate or severe TBI in adults; to date, no longitudinal DTI studies involving children with TBI have been published. Bendlin et al. [2008] reported decreases in FA in several major white matter tracts between 2 and 3 months and 12 months after TBI. Sidaros et al. [2008] reported simultaneous FA increases (internal capsule, centrum semi-ovale, and putamen) and FA decreases in the same patients (posterior corpus callosum). Moreover, Sidaros et al. reported that at 12 month follow-up, in subjects with good overall outcome, FA had increased to the level of that found in healthy controls in the internal capsule and centrum semi-ovale, while in individuals with poor overall outcomes, FA in these regions remained significantly lower than that of controls. For the corpus callosum and cerebral penduncle, FA remained low at 1 year in all TBI subjects, but those with good outcome demonstrated higher FA in these regions that those with poor outcome. Increasing FA over time after TBI may suggest a mechanism supporting functional recovery; this work will need to be replicated in children with consideration of age-related changes in FA associated with normal development [Bonekamp et al., 2007; Schmithorst et al., 2002] to better understand mechanisms underlying recovery and development following pediatric TBI.

SUSCEPTIBILITY WEIGHTED IMAGING

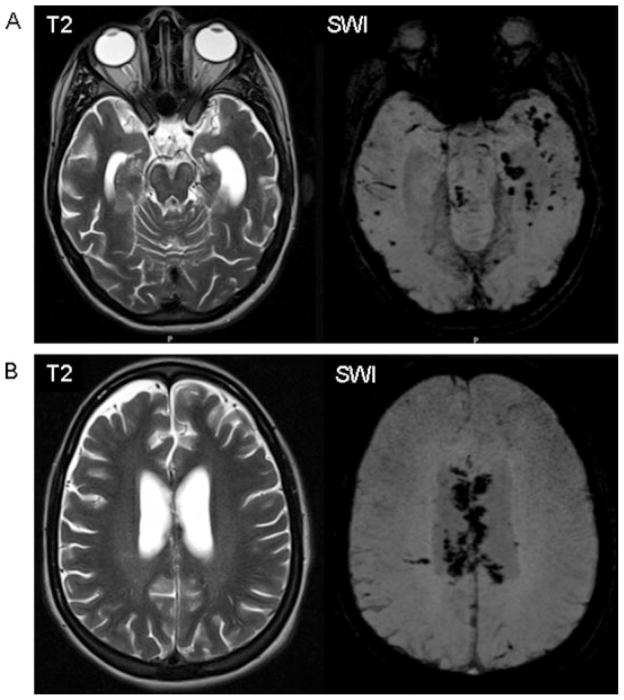

SWI exploits the distinct magnetic susceptibility effects of extracellular and extravascular blood products in the brain. By using a sequence that is highly susceptible to these magnetic susceptibility phenomena, such as three-dimensional T2★-weighted gradient echo sequences, miniscule hemorrhages can be detected early. These SWI sequences are significantly more sensitive than conventional MRI sequences or previously used two-dimensional T2★-weighted gradient echo sequences [Haacke et al., 2004]; in TBI, SWI is useful for detecting extravascular blood products such as those found in association with shearing injuries related to DAI [Tong et al., 2003]. In pediatric TBI, the use of SWI has been shown to increase lesion detection by up to 600% over gradient recalled sequences [Tong et al., 2003]. SWI identified a greater number and volume of shear injuries in children with lower initial GCS scores compared to children with higher initial GCS scores. Figure 2 demonstrates increased lesion identification with SWI in a teenager with TBI.

Fig. 2.

MRI images from a 16-year-old female 3 months after severe TBI. (A) T2-weighted axial MR image shows bilateral, left dominant hippocampal injury with significant tissue loss. No focal hemorrhages seen within the temporal lobes. Mild signal increase within the brainstem indicating Wallerian degeneration. SWI demonstrates many focal, petechial T2★-hypointense hemorrhages, representing DAI. (B) T2-weighted image shows faintly demarcated injury of the periventricular white matter and splenium of the corpus callosum. SWI demonstrates extensive hemorrhagic injury of the corpus callosum.

Lesion number and volume, as identified by SWI, appear to correlate with global and neurocognitive outcomes following pediatric TBI. In a study using SWI data acquired during acute hospitalization following TBI, the number of encountered lesions and lesion volume correlated with the number of days in coma. In addition, children with mild or no disability at 6–12 months following injury had fewer lesions and smaller total lesion volume than those children with worse global outcomes [Tong et al., 2004]. The same research group examined the relationship of SWI lesions, determined shortly after injury, to neuropsychological function 1–4 years following injury [Babikian et al., 2005]. They found that lesion number and volume were negatively correlated with intelligence quotient (IQ) and a composite neuropsychological index score. SWI lesion volume was found to account for 33% of the variance in full scale IQ and 44% of the variance in the neuropsychological index score.

1H-MAGNETIC RESONANCE SPECTROSCOPY

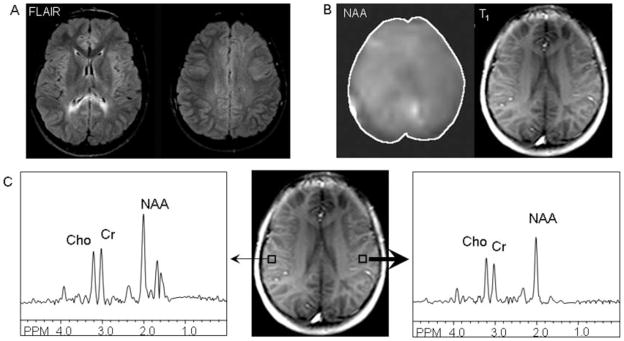

1H-Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) provides a noninvasive modality for assessing microscopic brain injury through quantitative analysis of the presence of key neurometabolites. The key metabolites measured by 1H-MRS include N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) which is believed to be a marker of neuronal density and integrity, creatine which is a marker of energy metabolism, and choline which is believed to be a marker of cell membrane turn over. Choline may be increased in active tissue injury, while NAA will decrease due to tissue loss and injury. In addition, 1H-MRS allows the measurement of lactate within the brain, which provides a marker of anaerobic metabolism and tissue injury due to ischemia or inflammation. Several studies to date have demonstrated decreases in NAA after TBI, including three studies of children [Parry et al., 2004; Walz et al., 2008; Yeo et al., 2006] as well as studies of adults with TBI [Friedman et al., 1998; Holshouser et al., 2006]. Figure 3 demonstrates MRS findings from an adolescent with a remote history of severe TBI.

Fig. 3.

MR and MR Spectroscopy images and data from a twelve-year-old male with severe TBI at age 5 years. (A) Axial FLAIR images demonstrating hyperintensities in bilateral periatrial white matter and superior anterior left frontal lobe. (B) N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA) map, obtained using a multislice spin-echo sequence with two-dimensional phase-encoding and outer-volume saturation pulses for lipid suppression, from the axial level demonstrated in the adjacent T1-weighted image; decreased intensity in the NAA map is noted in the left hemisphere, consistent asymmetric localization of DAI in FLAIR images. (C) Spectra derived from voxels in right (thin arrow) and left (thick arrow) hemipshere gray matter; decreased concentration of NAA, choline (Cho), and creatine (Cr) are noted in the left hemisphere compared with the right hemipshere.

Neurometabolite disturbance has been found to be predictive of overall outcome (good versus bad) following TBI in children [Ashwal et al., 2000]. 1H-MRS data acquired shortly after TBI has also been shown to have predictive value with regard to specific long-term cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Babikian et al. [2006] demonstrated that regional measures of ratios of NAA/choline and NAA/creatine obtained 1–2 weeks after TBI in children accounted for 40% of the variance in generalized measures of cognitive function obtained 1–4 years after TBI. Furthermore, they found correlations between regional NAA measures and specific neurocognitive domains, including attention and executive function. Additionally, investigators have demonstrated correlation between neurometabolite levels in the chronic phase of injury (greater than 1 year after injury) and concurrent measures of functioning in specific neurobehavioral domains for children after TBI. Parry et al. [2004] demonstrated a correlation between right frontal white matter choline/creatine ratio and reaction time in children aged 10–16 at the time of study. Walz et al. [2008] found that medial frontal gray matter creatine and choline correlated with parent report of social competence, and left frontal white matter choline and creatine correlated with parent report of internalizing behavioral problems, for children aged 6–9 at the time of study.

One study to date has reported on changes in 1H-MRS findings over time after TBI. Yeo et al. [2006] studied children aged 6–18 at the time of moderate to severe TBI. Although no change was noted in NAA, creatine, and choline values between 2.5 and 13 weeks after injury, an increase in NAA/choline and decrease in creatine/choline ratios were found between 3 and 21 weeks after TBI, suggesting some improvement in neurometabolite disturbances with time.

In summary, research to date suggests that greater burden of overall injury, as detected by any of a variety of anatomical and advanced neuroimaging methods, is associated with worse outcomes, both with regard to global function and specific neuropsychological domains. With increased sensitivity to DAI, the emerging MR imaging techniques discussed earlier hold promise for improving understanding of more specific brain-behavior relationships after pediatric TBI and for refining prognostication shortly after injury with regard to anticipated chronic deficits. Early evidence also suggests that these techniques may be useful for understanding mechanisms of recovery after pediatric TBI, though further longitudinal work is needed to understand the interplay between development, injury, and recovery in children with TBI. Identification of associations between focal areas of injury and specific long-term outcomes is complicated by the heterogeneity of injury, resulting in a need for large cohorts of subjects to achieve power necessary to link focal areas of injury with specific outcomes. Currently, use of dedicated, high-end imaging techniques may be limited due to the availability of necessary software and/or hardware as well as the time required for scan acquisition and their sensitivity to subject motion. However, should ongoing work continue to support the utility of these imaging modalities in TBI, future technical developments in automation of imaging processing and scanner capability may promote more widespread availability of advanced imaging techniques.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Grant number: K12HD001097.

References

- Arfanakis K, Haughton VM, Carew JD, et al. Diffusion tensor MR imaging in diffuse axonal injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:794–802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashikaga R, Araki Y, Ishida O. MRI of head injury using FLAIR. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:239–242. doi: 10.1007/s002340050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwal S, Holshouser BA, Shu SK, et al. Predictive value of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in pediatric closed head injury. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;23:114–125. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(00)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babikian T, Freier MC, Tong KA, et al. Susceptbility weighted imaging: neuropsychologic outcome and pediatric head injury. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;33:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babikian T, Freier MC, Ashwal S, et al. MR spectroscopy: predicting long-term neuropsychological outcome following pediatric TBI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:801–811. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Fritz H. Pathophysiology of traumatic injury in the developing brain: an introduction and short update. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2004;56:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendlin BB, Ries ML, Lazar M, et al. Longitudinal changes in patients with traumatic brain injury assessed with diffusion-tensor and volumetric imaging. Neuroimage. 2008;42:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson RR, Meda SA, Vasudevan S, et al. Global white matter analysis of diffusion tensor images is predictive of injury severity in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:446–459. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonekamp D, Nagae LM, Degaonkar M, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in children and adolescents: reproducibility, hemispheric, and age-related differences. Neuroimage. 2007;34:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander J, Cifu D, Wright JM, et al. The association of early computed tomography scan findings and ambulation, self-care, and supervision needs at rehabilitation discharge and at 1 year after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:214–220. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing-Cobbs L, Kramer L, Prasad M, et al. Neuroimaging, physical, and developmental findings after inflicted and noninflicted traumatic brain injury in young children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:300–307. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing-Cobbs L, Prasad M, Kramer L, et al. Acute neuroradiologic findings in young children with inflicted or noninflicted traumatic brain injury. Child Nerv Sys. 2000;16:25–34. doi: 10.1007/s003810050006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SD, Brooks WM, Jung RE, et al. Proton MR spectroscopic findings correspond to neuropsychological function in traumatic brain injury. Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1879–1885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway NR, Tong KA, Ashwal S, Oyoyo U, Obenaus A. Diffusion-weighted imaging improves outcome prediction in pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:1153–1162. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass A, Niendorf T, Hirsch JG. Acute and chronic changes of the apparent diffusion coefficient in neurological disorders––biophysical mechanisms and possible underlying histopathology. J Neurol Sci. 2001;186:S15–S23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry LR, Godersky JC, Thompson B, et al. Prospective comparative study of intermediate field MR and CT in the evaluation of closed head trauma. Am J Neuroradiol. 1988;9:91–100. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.3.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerring J, Brady K, Chen A, et al. Neuroimaging variables related to development of secondary attention deficit hyperactivity disorder after closed head injury in children and adolescents. Brain Inj. 2000;14:205–218. doi: 10.1080/026990500120682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grados MA, Slomine BS, Gerring JP, et al. Depth of lesion model in children and adolescents with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: use of SPGR MRI to predict severity and outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:350–358. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.3.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grados MA, Vasa RA, Riddle MA, et al. New onset obsessive-compulsive symptoms in children and adolescents with severe traumatic brain injury. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:398–407. doi: 10.1002/da.20398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke EM, Xu Y, Cheng YN, et al. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:612–618. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskovits EH, Megalooikonomous V, Davatzikos C, et al. Is the spatial distribution of brain lesions associated with closed-head injury predictive of subsequent development of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Analysis with brain-image database. Radiology. 1999;213:389–394. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv45389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holshouser BA, Tong KA, Ashwal S, et al. Prospective longitudinal proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging in adult traumatic brain injury. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:33–40. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins RO, Tate DF, Bigler ED. Anoxic versus traumatic brain injury: amount of tissue loss, not etiology, alters cognitive and emotional function. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:233–242. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman TA. Diffusion-weighted imaging: basic concepts and application in cerebral stroke and head trauma. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2283–2297. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1843-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman TA, Sorensen AG, Hergan K, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging for the evaluation of diffuse axonal injury in closed head injury. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:5–11. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman TA, Schwamm LH, Schaefer PW, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging as potential biomarker of white matter injury in diffuse axonal injury. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:370–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan HT, Runyan DK, Marshall SW, et al. A population-based comparison of clinical and outcome characteristics of young children with serious inflicted and noninflicted traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2004;114:633–639. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1020-L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc N, Chen S, Swank PR, et al. Response inhibition after traumatic brain injury (TBI) in children: impairment and recovery. Dev Neuropsychol. 2005;28:829–848. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2803_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Newberg A. Neuroimaging in traumatic brain injury. NeuroRx. 2005;2:372–383. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.2.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Wintermark M, Gean AD, et al. Focal lesions in acute mild traumatic brain injury and neurocognitive outcome: CT versus 3T MRI. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:1049–1056. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin H. Neuroplasticity following non-penetrating traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2003;17:665–674. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000107151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin HS, Mendelsohn D, Lily MA. Magnetic resonance imaging in relation to functional outcome of pediatric closed head injury: a test of the Ommaya-Gennarelli Model. Neurosurg Online. 1997;40:432–441. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199703000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin HS, Wilde EA, Chu Z, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in relation to cognitive and functional outcome of traumatic brain injury in children. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2008;23:197–208. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000327252.54128.7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max JE, Schachar RJ, Levin HS, et al. Predictors of secondary attention-deficit/hyper-activity disorder in children and adolescents 6 to 24 months after traumatic brain injury. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:1041–1049. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000173292.05817.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max JE, Levin HS, Schachar RJ, et al. Predictors of personality change due to traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents six to twenty-four months after injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;18:21–32. doi: 10.1176/jnp.18.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry L, Shores A, Rae C, et al. An investigation of neuronal integrity in severe paediatric traumatic brain injury. Child Neuropsychol. 2004;10:248–261. doi: 10.1080/09297040490909279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick PD, Mabry JL, Gurka MJ, et al. MRI patterns in prolonged low response states following traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents. Brain Inj. 2007;21:63–68. doi: 10.1080/02699050601111401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power T, Catroppa C, Coleman L, et al. Do lesion site and severity predict deficits in attentional control after preschool traumatic brain injury (TBI)? Brain Inj. 2007;21:279–292. doi: 10.1080/02699050701253095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salorio CF, Slomine BS, Grados MA, et al. Neuroanatomic correlates of the CVLT-C performance following pediatric traumatic brain injury. JINS. 2005;11:686–696. doi: 10.1017/S1355617705050885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmithorst VJ, Wilke M, Dardzinski BJ, et al. Correlation of white matter diffusivity and anisotropy with age during childhood and adolescence: a cross-sectional diffusion-tensor MR imaging study. Radiology. 2002;222:212–218. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2221010626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer M, Stouter J, Hart T, et al. Computed tomography findings and early cognitive outcome after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2006;20:997–1005. doi: 10.1080/02699050600677055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidaros A, Engberg AW, Sidaros K, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging during recovery from severe traumatic brain injury and relation to clinical outcome: a longitudinal study. Brain. 2008;131:559–572. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomine BS, Gerring JP, Grados MA, et al. Performance on measures of executive function following pediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2002;16:759–772. doi: 10.1080/02699050210127286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HG, Alden J. Age-related differences in outcomes following childhood brain insults: an introduction and overview. JINS. 1997;3:555–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong KA, Ashwal S, Holshouser BA, et al. Hemorrhagic shearing lesions in children and adolescents with posttraumatic diffuse axonal injury: improved detection and initial results. Radiology. 2003;227:332–339. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272020176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong KA, Ashwal S, Holshouser BA, et al. Diffuse axonal injury in children: clinical correlation with hemorrhagic lesions. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:36–50. doi: 10.1002/ana.20123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasa RA, Grados M, Slomine B, et al. Neuroimaging correlates of anxiety after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55:208–216. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00708-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verger K, Junque C, Levin HS, et al. Correlation of atrophy measures on MRI with neuropsychological sequelae in children and adolescents with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2001;15:211–221. doi: 10.1080/02699050010004059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz NC, Cecil KM, Wade SL, et al. Late proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy following traumatic brain injury during early childhood: relationship with neurobehavioral outcomes. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:94–103. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warach S, Gaa J, Siewert B, et al. Acute human stroke studied by whole brain echo planar diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:231–241. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde EA, Hunter JV, Newsome MR, et al. Frontal and temporal morphometric findings on MRI in children after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:333–344. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde EA, Chu Z, Bigler ED, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in the corpus callosum in children after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1412–1426. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde EA, McCauley SR, Hunter JV, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of acute mild traumatic brain injury in adolescents. Neurology. 2008;70:948–955. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000305961.68029.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak JR, Krach L, Ward E, et al. Neurocognitive and neuroimaging correlates of pediatric traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) study. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22:555–568. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo RA, Phillips JP, Jung RE, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy detects brain injury and predicts cognitive functioning in children with brain injuries. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1427–1435. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan W, Holland SK, Schmithorst VJ, et al. Diffusion tensor MR imaging reveals persistent white matter alteration after traumatic brain injury experienced during early childhood. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1919–1925. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]