Abstract

The aim of this study was to show whether connexin43 (C×43) expression in gonads is affected by an anti-androgen action. To perform this test, pigs were prenatally (on gestational days 20–28 and 80–88; GD20, GD80) and postnatally (on days 2–10 after birth; PD2) exposed to flutamide, which was given in five doses every second day and its effect was observed in prepubertal gilts and boars. Morphology and expression of C×43 was investigated in testes and ovaries by means of routine histology, immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, and RT-PCR. In boars exposed to flutamide varying degrees of seminiferous tubule abnormality, including reduced number of Sertoli cells, tubules with severely dilated lumina and multinucleated germ cells were observed, whereas in gilts, the administration of flutamide at GD20 resulted in delayed folliculogenesis. Only follicles at the preantral stage were observed. Qualitative analysis of immunohistochemical staining for C×43 was confirmed by quantitative image analysis, where the staining intensity was expressed as relative optical density of diaminobenzidine deposits. After flutamide exposure, statistically significant increase in C×43 signal intensity was observed between interstitial tissue of GD20 and control pigs (**P<0.01), between seminiferous tubules of PD2 and control boars (**P<0.01) and between theca cells of GD80, of PD2 and control gilts (**P<0.01). In contrast, statistically significant decrease in C×43 signal intensity was found between granulosa cells of GD20, of PD2 and control gilts (**P<0.01 and *P<0.05, respectively) and between theca cells of GD20 and control gilts (**P<0.01). Since we demonstrated changes in gonad morphology and in the expression of C×43 at the level of protein of prepubertal boars and gilts, it seems possible that flutamide, through blocking androgen action, causes delayed gonadal maturation in later postnatal life and, among other factors, may be involved in the regulation of C×43 gene expression in pig gonads.

Key words: C×43 gene expression, testis, ovary, flutamide, prepubertal pigs.

Introduction

A growing number of animal studies show that environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals, including anti-estrogens and anti-androgens, have the potential to affect reproductive development and function of male and female gonads.1–3 Suspected androgenic chemicals or anti-androgens are known to hinder androgen action by inhibiting receptor binding of androgen and/or nuclear retention of the androgen complex. As a consequence, reproductive tissues are frequently abnormally developed or under-developed.4 The effects of flutamide and of another anti-androgen, vinclozolin, on the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis have been demonstrated in rats.5–8 In pigs, only one study describes the effect of maternal flutamide exposure on male offspring,9 whereas scarce information is available regarding possible impact of anti-androgens on the proteins involved in the gap junctional communication within the gonads.

Gap junctions provide the pathways for metabolic and electrical intercellular communication. It is well established that the cell-to-cell communication in testes and ovaries is mediated by gap junctions channels, predominantly comprising connexin 43 (C×43) protein.10–14 C×43 is thought to play an important role on the control of gonad development,15,16 spermatogenesis and folliculogenesis.17–20 Direct evidence of the role of C×43 gap junctions in reproduction has been shown in mice missing the C×43 gene.21–22 In mind to show whether androgens are involved in the regulation of gap junctional communication, we sought to demonstrate whether prenatal and neonatal exposure of the antiandrogen flutamide had an effect on the expression of C×43 in male and female gonads of prepubertal pigs. Previously, we have demonstrated the effectiveness of flutamide at the dose of 50 mg/kg b.w. that was manifested by the alterations in anogenital distance as the early marker of androgenicity.23 It should be added that in the study by Durlej et al.23 we found no obvious changes in gonad morphology and in C×43 expression of neonatal pig offspring after in utero exposure to flutamide.23 In this context, the question arises whether flutamide is able to exert its effect later in postnatal life. This was investigated by means of routine histology, qualitative and quantitative immunohistochemistry, Western blot and RT-PCR.

Materials and Methods

Animals and experimental design

Three-month-old prepubertal pigs (n=24) (Large White × Polish Landrace) originating from six litters were allotted into three groups of experimental animals of each gender and respective control groups. The first two groups of experimental animals were exposed prenatally on gestational days 20–28, and 80–88 (GD20 and GD80) to an anti-androgen flutamide (2-methyl-N-[4-nitro-3-(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl]propamide; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). The third group was treated with flutamide postanatally on days 2–10 after birth (PD2). The control animals of each gender were given a vehicle only (corn oil). Flutamide was given in five doses (50 mg/kg body weight; every second day). Dose and time of exposure to flutamide were based on the literature and on our own data, previously described in detail.23

The testes and ovaries were obtained from 90–100-day-old animals, irrespective of the time of flutamide exposure. All surgical procedures were performed by a veterinarian and followed approved guidelines for the ethical treatment of animals in accordance with the Polish legal requirements under the licence given by the Local Ethics Committee at the Jagiellonian University (No. 4/2008).

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry

Both testes and ovaries were cut into small cubes and immersion-fixed in either Bouin's fixative or in paraformaldehyde (PFA; 4%, v/v) for routine histology (haematoxylin-eosin staning, H–E) and immunohistochemistry, respectively. Then, dehydrated in an increasing gradient of ethanol, cleared in xylene, embedded in paraplast (Monoject Scientific Division of Scherwood Medical, St Louis, MO, USA) and cut at 5 µm thick sections. Other tissue fragments were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA and protein extraction.

After dewaxing and rehydration, sections were heated in a microwave to optimize immunohistochemical staining. The whole procedure has been previously described in detail.24 Briefly, the sections were incubated in the presence of a rabbit polyclonal antibody against C×43 (a final concentration of 0.25 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich). Next, biotinylated secondary antibody, goat anti-rabbit IgG (a final concentration 5 µg/mL; Vector Lab., Burlingame CA, USA) was applied. Finally, avidinbiotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex (ABC/HRP; Dako/AS, Glostrup, Denmark) was used. Peroxidase activity was visualized by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich). Sections incubated with normal goat serum instead of primary antibody were used as negative controls. All sections were examined with a Nikon Eclipse microscope (Japan) using bright field illumination.

Qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the immunohistochemical reactions

Immunohistochemical staining for C×43 was evaluated qualitatively in at least 20 serial sections of testes and ovaries from each experimental group. The slides were processed immunohistochemically at the same time and with the same treatment, in order to obtain comparable C×43 staining intensities. The cells were considered immunopositive if brown reaction product was present and appeared as a signal between testicular cells and between ovarian cells; the cells without any specific immunostaining were considered immunonegative.25

In order to evaluate quantitatively the immunohistochemical reaction intensity, digital color images were obtained by a CCD Video Camera (KY-F55, JVC) mounted on an optical microscope (Microphot, Nikon, Japan) and connected to a video capture card (PV-BT878P, Prolink, Taiwan), installed on a personal computer. Images of the testes (seminiferous tubules and interstitial tissue) and ovaries (granulosa cells and interstitial tissue) were captured by a 20× objective, as previously described.23 Image processing and analyses were performed using the public domain ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The intensity of the immunohistochemical reaction was expressed as relative optical density (ROD) of diaminobenzidine brown reaction products and calculated by means of the formula described by Smolen.26 A total number of 64 testicular and ovarian sections (n=8 per group) were subjected to image analysis. The results of 10 separate measurements for each of testicular and ovarian compartments were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical differences were assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's post hoc comparison test.

Western blot analysis

Tissues were homogenized on ice with a cold Tris/EDTA buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, 1 mmol/L EDTA, pH 7.5), sonicated and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C as previously described.27 In brief, the protein concentration for each sample was estimated using the Bradford dye-binding procedure with BSA as a standard.28 Homogenates containing 20 µg of protein were solubilized in a sample buffer (Bio-Rad Labs, GmbH, München, Germany) and heated at 99.9°C for 3 min. After denaturation the samples were subjected to electrophoresis on SDS-PAGE gels (12%, v/v), according to Laemmli.29 Separated proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane using a wet blotter in the Genie Transfer buffer (pH 8.4) for 90 min at a constant voltage of 135V. Then, blots were blocked overnight at 4°C with shaking in a solution of non-fat dry milk (5%, w/v) in TBST, followed by incubation with rabbit polyclonal antibody against C×43 (a final concentration of 0.0625 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1.5 h at room temperature. β-actin was used as an internal control (a final concentration of 1.0 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich). The membranes were washed and incubated with a goat anti–rabbit IgG linked to the horseradish-peroxidase (a final concentration of 0.5 µg/mL; Vector Lab.) for 1h at room temperature. Then, bound antibody was revealed using 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine as the substrate (DAB; 0.5 mg/mL). Finally, the membranes were dried and then scanned using Epson Perfection Photo Scanner (Epson Corporation, CA, USA). Molecular mass was estimated by reference to standard proteins (Fermentas, GmbH, St. Leon-Rot, Germany). For positive controls pig heart was used.

Reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction

Total cellular RNA from pig testes and ovaries was isolated using Nucleo Spin RNA II (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany), following the manufacturer's instruction. Oligonucleotide primers pairs were constructed (Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics PAS, Poland) based on the sequence of the porcine C×43 gene30 (5′-GGTGGACTGTTTCCTCTCTCG-3′ and 5′-GGAGCAGCCATTGAAATAAGC-3′). For the loading control the porcine GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3 phosphate dehydrogenase) gene was used30 (5′-GGACTCATGACCACGGTCCAT-3′ and 5′ TCAGATCCACAACCGACACGT-3′). The whole procedure was previously described.31 Briefly, complementary DNA was synthesized from total RNA (1µg) using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Corp., Camarillo CA, USA). PCR amplification was performed in a total reaction volume of 10 µL containing 1 µL of cDNA template, 10 µmol/L forward and reverse primers, 10 mmol/L of dinucleotide triphosphate, 10 × PCR buffer and 2 units of DyNAzyme II polymerase (Finnzymes, Finland). PCR conditions were: 1× (95°C for 4 min), 35× (95°C for 30 sec, 65°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 45 sec) for C×43, and 1× 94°C for 4 min, 35× (94°C for 45 sec, 57°C for 45 sec, 72°C for 90 sec) for GAPDH, and 72°C for 7 min. Genomic DNA amplification contamination was checked periodically by control experiments, where reverse transcriptase was omitted during the RT step. All PCR products (7.5 µL of 10 µL total reaction volume) were electrophoresed in agarose gels (1.5%, w/v) containing ethidium bromide and visualized over UV light. The sizes of the PCR products were estimated by reference to the 100 bp DNA Marker (Promega, Southampton, UK).

Results

Male and female gonad morphology

Testes and ovaries of immature control pigs exhibited a typical morphology. More precisely, in well-developed interstitial tissue the Leydig cell clusters were seen, while Sertoli cells, prespermatogonia and spermatogonia were observed in the seminiferous tubules. The latter frequently moved through the lineage of Sertoli cells to the basal lamina (Figure 1A). In ovarian sections, numerous preantral and antral follicles with normally developed compartments were observed (Figure 2A–B).

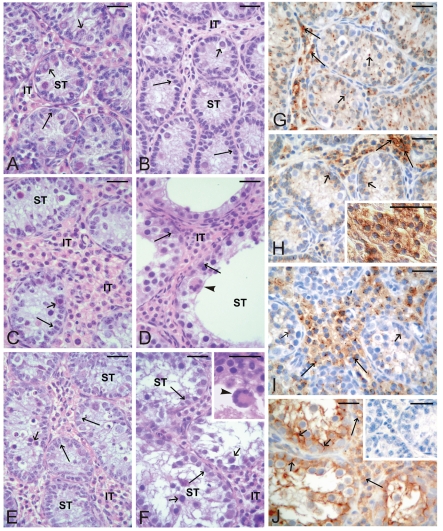

Figure 1.

Testes histology of prepubertal control pigs (A) and flutamide exposed pigs at GD20 (B), GD80 (C–D), PD2 (E–F) and immunolocalization of C×43 in testes of prepubertal control pigs (G) and flutamide exposed pigs at GD20 (H), GD80 (I) and PD2 (J). Seminiferous tubules (ST); Interstitial tissue (IT). Scale bars represent 20 µm. (A) Well-developed interstitial tissue with Leydig cell clusters and seminiferous tubules with Sertoli cells (arrows); prespermatogonia (small arrows) and spermatogonia are visible. (B) Normal structure of testicular compartments is visible. (C–F) Varying degrees of tubule abnormality are present, ranging from completely normal tubules to abnormal tubules. Note a distinct increase of the interstitial space, presence of numerous Leydig cells (C), severely dilated lumina (D), numerous prespermatogonia (small arrow) in the center of seminiferous tubules (E), regressed tubules (F) and multinucleated germ cells (arrowheads) (D; at higher magnification, insert in F). (G) Linear pattern of the staining between neighboring Leydig cells (arrows) and the focal pattern between Sertoli cells and germ cells (small arrows) are visible. (H) Very strong intensity of the staining between neighboring Leydig cells (arrows), (at higher magnification, insert in H). Weak staining intensity between Sertoli cells and germ cells (small arrows). (I) Moderate to strong intensity of the staining between Leydig cells (arrows). Note a further decrease in the staining intensity between Sertoli cells and germ cells (small arrows). (J) Strong-to-very strong intensity of the staining is observed between testicular cells of both compartments. Note a distinct linear pattern of the staining between Sertoli cells and remaining germ cells. No positive staining is visible when the primary antibody is omitted (an insert).

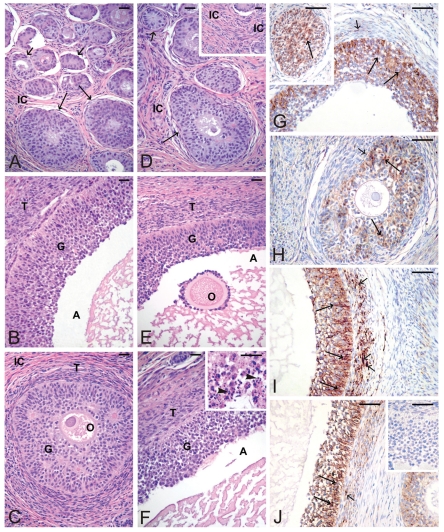

Figure 2.

Ovaries histology of prepubertal control pigs (A–B) and flutamide exposed pigs at GD20 (C), GD80 (D–E), PD2 (F) and immunolocalization of C×43 in ovaries of prepubertal control pigs (G) and flutamide exposed pigs at GD20 (H), GD80 (I), and PD2 (J). Interstitial cells (IC); Granulosa cells (G); Theca cells (T); Antrum (A); Oocyte (O). Scale bars represent 20 µm. (A) Numerous preantral follicles (small arrows) and antral follicles (arrows) with well-developed compartments are visible. (B) Granulosa and theca cell layers and antrum are seen. (C) A follicle at the preantral stage is seen. (D–E) Normal preantral follicle (arrow) and abnormal antral follicle are observed. Note a distinct increase of the interstitial cell space (insert in D). (F) Normal folliculogenesis is observed. Note some antral follicles containing apoptotic granulosa cells (arrowheads) (at higher magnification, insert in F). (G) Positive staining for C×43 between adjacent granulosa cells (arrows) and between theca cells (small arrow) of preantral (an insert) and antral follicles. (H) A decline of the staining intensity between granulosa cells (arrows) is observed. Very weak staining in theca cells is visible (small arrow). (I) Strong intensity of the staining between adjacent granulosa cells of antral follicles (arrows). Note a distinct increase in the staining intensity within theca cells (small arrows). (J) A similar pattern of the staining and its differential intensity compared to (G). Note a moderate-to-strong intensity of the staining between granulosa cells (arrows) and between theca cells (small arrow). No positive staining is visible when the primary antibody is omitted (insert in J).

Varying degrees of seminiferous tubule abnormality, including reduced number of Sertoli cells mainly present at GD20 boars (Figure 1B), were observed in testes of boars following exposure to flutamide, while tubules with severely dilated lumina (Figure 1C–F) and multinucleated germ cells were frequently seen in GD80 and PD2 boars (Figure 1D, F).

Exposure of gilts to flutamide at GD20 resulted in delayed folliculogenesis. In such ovaries, only follicles at the preantral stage and younger were observed (Figure 2C), whereas in ovaries from pigs exposed to flutamide at GD80 either failure in developing follicles (Figure 2D) or abnormal antral follicles were noticed (Figure 2E). Moreover, the thickening of the interstitial cell layer was observed (Figure 2D, insert). A normal folliculogenesis was seen in the pig ovaries exposed to flutamide from PD2; however, some antral follicles contained apoptotic granulosa cells (Figure 2F, insert), which were identified by the TUNEL assay (not shown).

C×43 localization and expression in testes and ovaries

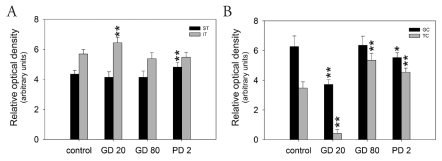

Qualitative analysis of immunohistochemical staining for C×43 (Figures 1G–J, 2G–J) was confirmed by quantitative image analysis, in which the staining intensity was expressed as relative optical density of diaminobenzidine deposits (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Quantitative analysis of the intensity of C×43 staining expressed as relative optical density (ROD) of diaminobenzidine brown reaction products in testicular (A) and ovarian (B) compartments of pigs exposed to flutamide vs respective controls. The values expressed are the mean ± SD (n=10). Statistically significant difference between means from control was analysed by ANOVA (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). ST, Seminiferous tubules; IT, Interstitial tissue; GC, Granulosa cells; TC, Theca cells.

In testes removed from control pigs, a focal to linear localization of the C×43 protein was observed in the interstitial tissue on the cellular membrane between neighboring Leydig cells, whereas a focal signal only was observed in the seminiferous tubules between the adjacent Sertoli cells and between Sertoli cells and germ cells (Figure 1G). After flutamide exposure, it was observed a distinct increase in C×43 signal intensity in the interstitial tissue of GD20 pigs and in the seminiferous tubules of PD2 vs control males (Figure 1H, 1J) and differences were found as statistically significant (**P<0.01) (Figure 3A). Interestingly, the distribution of the reaction product between Sertoli cells of PD2 males was mainly linear (Figure 1J), whereas in the interstitial tissue the pattern of staining was similar to the control one. However, after flutamide exposure at GD80 no statistically significant differences in the intensity of C×43 staining were found either in the interstitial tissue or in the seminiferous tubules when compared with the control (Figure 1I, Figure 3A).

In the ovaries of control pigs, C×43 signal was localized in the adjacent granulosa cells of preantral and antral follicles (Figure 2G). After flutamide exposure, the pattern of C×43 staining was similar to the control, while the intensity of staining varied in comparison with the control (Figure 2H–J). There was a significant decrease in the C×43 expression in the granulosa cells of GD20 (**P<0.01) and PD2 pigs (*P<0.05), as well as in the theca cells of GD20 pigs (**P<0.01) compared with the control. In contrast, flutamide exposure at GD80 and PD2 caused statistically significant increase in the staining intensity within theca cells (**P<0.01), (Figure 2I–J, Figure 3B). For details, see Table 1. Whatever the tissue, when the primary antibody was omitted, no positive staining for C×43 was detected (Figures 1J, 2J inserts).

Table 1. The intensity of C×43 staining expressed as relative optical density of diaminobenzidine brown reaction products in testicular and ovarian compartments of pigs exposed to flutamide vs respective controls.

| Relative Optical Density | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | GD20 | GD80 | PD2 | |

| Testes | ||||

| Semeniferous tubules | 4.35±0.25 | 4.14±0.37 | 4.14±0.41 | 4.82±0.31** |

| Interstitial tissue | 5.69±0.29 | 6.44±0.36** | 5.38±0.41 | 5.47±0.33 |

| Ovaries | ||||

| Granulosa cells | 6.27±0.72 | 3.72±0.33** | 6.35±0.62 | 5.53±0.33* |

| Theca cells | 3.47±0.42 | 0.42±0.25** | 5.35±0.46** | 4.54±0.28** |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD, they are statistically different at *P<0.05 level or at **P<0.01.

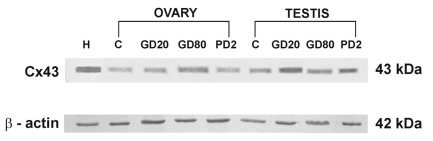

In Western-blot analysis of all ovarian and testicular homogenates C×43 appeared as a single band of approximately 43 kDa (Figure 4). The intensity of immunoblots was slightly higher in testes and ovaries of flutamide exposed pigs than in the control ones. The analysis identified a 43 kDa band in pig heart as well, run as a positive control (Figure 4). β-actin as an internal control appeared as a band of 42 kDa (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of C×43 in ovaries and testes of prepubertal pigs. Lane H indicates pig heart used as the positive control. Further lanes indicate ovarian and testicular samples of control pigs (C) and of those exposed to flutamide at GD20, GD80, and PD2. β-actin indicates an internal control.

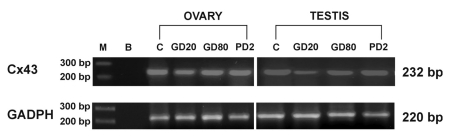

Electrophoresis revealed the PCR-amplified products of predicted sizes: 232 bp for C×43 and 220 bp for GAPDH. Screening for C×43 expression revealed the presence of a transcript in all examined testicular and ovarian samples corresponding to different time of flutamide exposures (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Demonstration of C×43 gene expression and GAPDH as a loading control in ovaries and testes of prepubertal pigs. Lane M contains a molecular weight marker. Lane B indicates blank samples. Further lanes indicate ovarian and testicular samples of control pigs (C) and of those exposed to flutamide at GD20, GD80, and PD2. The sizes of the PCR products are indicated on the right.

Discussion

The results presented herein demonstrate that exposure to flutamide at different time of porcine development, has a potential to induce adverse effects on the gonad morphology and to change the expression of C×43 protein in testes and ovaries of prepubertal pigs.

The treatment with flutamide at GD20, GD80 and PD2 caused varying degrees of seminiferous tubule abnormality including reduced number of Sertoli cells and delayed testicular maturation. According to De Franca et al.,32 the inadequate Sertoli cell number causes a demasculinized testis. It is therefore possible that the reduced Sertoli cell number, following flutamide exposure, causes the tubule alterations observed in prepubertal boars. Furthermore, upon GD20 and PD2 we observed the appearance of multinucleated germ cells, being perhaps a result of inappropriate cell division, although Kleymenova et al.,33 suggested that the formation of multinuclear germ cells in the fetal rat testis is caused by a disruption of Sertoli-germ cell contacts after di(n-butyl) phthalate treatment. However, it should be emphasized that di(n-butyl) phthalate exerts anti-androgenic effect by inhibition of testosterone production and not of testosterone action.

Overall, the results obtained from flutamide-treated pigs and those from the respective controls correspond to data described for male rodents5,34–36 except for cryptorchidism, frequently observed in rats exposed to flutamide,5,37,38 but not in our study.

An impaired folliculogenesis, mostly manifested by the presence of preantral follicles, in prepubertal females was observed only in utero in GD20 exposed gilts, though failure in developing follicles and abnormal antral follicles were noticed in GD80 gilts.

Since no changes in gonad morphology have previously been demonstrated in neonatal piglets in utero exposed to flutamide,23 we suggest that in GD20 gilts a delayed gonadal maturation appears in later postnatal life. Our preliminary data on adult pigs (unpublished data) seem to confirm the idea that flutamide causes delayed effects, later in adult life.

Moreover, we provided immunohistochemical evidence that Leydig cells, Sertoli cells, granulosa cells and theca cells are the main cells expressing C×43 in immature pig testis and ovary, as described mostly in rodents. In male rats, cell- and age-dependent distribution of C×43 has been reported by Risley et al.15 They showed that in Leydig cells, C×43 expression increases with age, with maximal levels in the adult, while in Sertoli cells the C×43 content is maximal in immature testes. Similarly, we observed a strong signal for C×43 between Sertoli cells and germ cells in control pigs; however, a decreased intensity of C×43 staining, although not statistically significant, was observed within the seminiferous tubules in prenatally exposed boars. Interestingly, the highest C×43 signals were demonstrated in the interstitial compartment of GD20 boars and in the tubular compartment of PD2 males. Differential response to flutamide may reflect a possible ability of flutamide to antagonize certain androgenic effects but agonize others, as described in breast cancer cells.39 A high testosterone level after birth could explain lack of alterations in the C×43 protein level within the interstitium of PD2 boars, which could not effectively be blocked by the used flutamide dose.

Recently, the effect of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate on gap and tight junction protein expression has been demonstrated in the testis of prepubertal rats.40 This toxicant caused a down-regulation of C×43 by inducing germ cell sloughing from the tubules.

Gap-junctional coupling provided by C×43 channels is also necessary for ovarian folliculogenesis, as demonstrated in mouse and pig.20,41,42 Our results confirm the studies by Wright et al.43 and Granot and Dekel44 demonstrating the C×43 expression in the granulosa cells during follicle maturation. These authors suggested that the follicles, being hormone responsive, reflect the influence of hormones on the gap junction expression. In turn, the expression pattern reflects developmental regulation, since growing follicles express C×43 gap junction protein earlier on.

In prepubertal gilts flutamide exposure induced significant alterations in the ovarian C×43 expression. It is likely that the effect of flutamide on the female gonad is more pronounced than in the male one, because the androgen levels in females are low and could be blocked by the anti-androgen used. As shown in Figure 3 and Table 1, there were statistically significant differences in C×43 signal intensity between granulosa cells of GD20 and PD2 pigs, as well as between theca cells of all flutamide-treated gilts compared with controls. Interestingly, C×43 expression in theca cells was found to be highest in GD80 and lowest in GD20 gilts, indicating a differential response to flutamide, as demonstrated in the male pigs. A significant reduction in the expression of C×43 in GD20 ovaries with concomitant lack of the antral follicles suggests flutamide as targeting C×43 protein and affecting the process of follicle development. Moreover, this indicates that the expression of C×43 protein in the ovarian cells of prepubertal pigs is regulated, among other factors, by androgens. On the other hand, C×43 mRNA levels were found as not generally regulated by androgens, except for GD20 testes that showed a clear down-regulation. The latter corresponds to the earlier study demonstrating an androgen-mediated reproductive development in male rat offspring following exposure to flutamide at early gestational age34 However, the main difficulty in understanding the steroid hormones role on gap junctional communication in testes and ovaries comes from the fact that each gender gonads are composed by several cell types, which activity is controlled by various endo-, para-, and/or autocrine factors. In a very recent review, Lui and Lee45 have summarized the molecular mechanisms by which hormones (FSH and testosterone) and cytokines regulate cell junction restructuring in the testis.

Overall, the present findings revealed that androgens are somehow involved in the regulation of C×43 gap junction communication in the gonads of prepubertal pigs. The question arises on how gene expression for the C×43 is affected by the anti-androgen flutamide, which has an influence on the gonad development stage and may interfere with extrinsic and/or intrinsic signaling pathways in the pig gonads.

Acknowledgment:

this work was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, a grant N N303339835 and in part, by The Foundation for Polish Science, an Academic Grant 2008, from the Mistrz Programme (to B.B). Part of this work was presented at the VIII International Conference of Pig Reproduction, Banff, Canada, 2009.

References

- 1.Nicolopoulou-Stamati P, Pitsos MA. The impact of endocrine disrupters on the female reproductive system. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:323–30. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards TM, Moore BC, Guillette LJ., Jr Reproductive dysgenesis in wildlife: a comparative view. Int J Androl. 2006;29:109–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uzumcu M, Zachow R. Developmental exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors: consequences within the ovary and on female reproductive function. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23:337–52. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anahara R, Toyama Y, Mori C. Review of the histological effects of the anti-androgen flutamide on mouse testis. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25:139–43. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassim NM, McDonald SW, Reid O, Bennett NK, Gilmore DP, Payne AP. The effect of pre- and postnatal exposure to the nonsteroidal antiandrogen flutamide on testis descent and morphology in the Albino Swiss rat. J Anat. 1997;190:577–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1997.19040577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray LE, Wilson VS, Stoker T, Lambright C, Furr J, Norwega N, et al. Adverse effects of environmental antiandrogens and androgens on reproductive development in mammals. Int J Androl. 2006;29:96–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamsson NA, Brokken LJS, Paranko J, Toppari J. In vivo and in vitro effects of flutamide and diethylstilbestrol on fetal testicular steroidogenesis in the rat. Reprod Toxicol. 2008;25:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loutchanwoot P, Wuttke W, Jarry H. Effects of a 5-day treatment with vinclozolin on the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis in male rats. Toxicology. 2008;243:105–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMahon DR, Kramer SA, Husmann DA. Antiandrogen induced cryptorchidism in the pig is associated with failed gubernacular regression and epididymal malformations. J Urol. 1995;154:553–57. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199508000-00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidder GM, Mhawi AA. Gap junctions and ovarian folliculogenesis. Reproduction. 2002;123:613–20. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1230613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saez JC, Berthoud VM, Branes MC, Martinez AD, Bneyer EC. Plasma membrane channels formed by connexins: their regulation and functions. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1359–400. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pointis G, Segretain D. Role of connexin-based gap junction channels in testis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:300–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmiero C, Ferrara D, De Rienzo G, d'Istria M, Minucci S. Ethane 1,2-dimethane sulphonate is a useful tool for studying cell-to-cell interactions in the testis of the frog Rana esculenta. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2003;131:38–47. doi: 10.1016/s0016-6480(02)00627-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gershon E, Plaks V, Dekel N. Gap junctions in the ovary: Expression, localization and function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;282:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Risley MS, Tan IP, Roy C, Saez JC. Cell-age- and stage-dependent distribution of connexin 43 gap junctions in testes. J Cell Sci. 1992;103:81–96. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melton CM, Zaunbrecher GM, Yoshizaki G, Patiño R, Whisnant S, Rendon A, et al. Expression of connexin 43 mRNA and protein in developing follicles of prepubertal porcine ovaries. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;130:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Batias C, Siffroi JP, Fenichel P, Pointis G, Segretain D. Connexin43 gene expression and regulation in the rodent seminiferous epithelium. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:793–805. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bravo-Moreno JF, Diaz-Sanchez V, Montova-Flores JG, Lamovi E, Saez JC, Perez-Armendariz EM. Expression of connexin43 in mouse Leydig Sertoli, and germinal cells at different stages of postnatal development. Anat Rec. 2001;264:13–24. doi: 10.1002/ar.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izzo G, d'Istria M, Ferrara D, Serino I, Aniello F, Minucci S. Connexin 43 expression in the testis of the frog Rana esculenta. Zygote. 2006;14:349–57. doi: 10.1017/S096719940600390X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackert CL, Gittens JE, O'Brien MJ, Eppig JJ, Kidder GM. Intercellular communication via connexin 43 gap junctions is required for ovarian folliculogenesis in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2001;233:258–70. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juneja SC, Barr KJ, Enders GC, Kidder GM. Defects in the germ line and gonads of mice lacking connexin 43. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:1263–70. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.5.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brehm R, Zeiler M, Rüttinger C, Herde K, Kibschull M, Winterhager E, et al. A Sertoli cell-specific knockout of connexin43 prevents initiation of spermatogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:19–31. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durlej M, Kopera I, Knapczyk-Stwora K, Hejmej A, Duda M, Koziorowski M, et al. Connexin 43 gene expression in male and female gonads of porcine offspring following in utero exposure to an anti-androgen flutamide. Acta Histochem. 2009 Oct 21; doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2009.07.001. [Epub] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotula-Balak M, Hejmej A, Sadowska J, Bilinska B. Connexin 43 expression in human and mouse testes with impaired spermatogenesis. Eur J Histochem. 2007;51:261–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hejmej A, Kotula-Balak M, Sadowska J, Bilinska B. Expression of connexin 43 protein in testes, epididymides, and prostates of stallions. Equine Vet J. 2007;39:122–7. doi: 10.2746/042516407x169393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smolen AJ. Image analytic techniques for quantification of immunocytochemical staining in the nervous system. In: Conn PM, editor. Methods in Neurosciences. Academic Press; San Diego: 1990. pp. 208–29. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hejmej A, Kopera I, Kotula-Balak M, Gizejewski Z, Bilinska B. Age-dependent pattern of connexin 43 expression in testes of European bison (Bison bonasus, L.) J Exp Zool. 2009;311A:667–75. doi: 10.1002/jez.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Y, Inouen N, Matsuda-Minehata F, Goto Y, Maeda A, Manabe N. Changes in expression and localization of connexin 43 mRNA and protein in porcine ovary granulosa cells during follicular atresia. J Reprod Dev. 2005;51:627–37. doi: 10.1262/jrd.17035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knapczyk-Stwora K, Durlej M, Duda M, Czernichowska-Ferreira K, Tabecka-Lonczynska A, Slomczynska M. Expression of estrogen receptor α (ERα) and estrogen receptor β (ERβ) in the uterus of the pregnant swine. Reprod Dom Anim. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2009.01505.x. doi: 0.1111/j.1439 531.2009.01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Franca LR, Hess RA, Cooke PS, Russell LD. Neonatal hypothyroidism causes delayed Sertoli cell maturation in rats treated with propylthiouracyl: evidence that the Sertoli cells controls testis growth. Anat Rec. 1995;242:57–69. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092420108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleymenova E, Swansson C, Boekelheide K, Gaido KW. Exposure in utero to di-(n-butyl)phthalate alters the vimentin cytoskeleton of fetal rat Sertoli cells and disrupts Sertoli cell-gonocyte contact. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:482–90. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.037184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foster PMD, Harris MW. Changes in androgen-mediated reproductive development in male rat offspring following exposure to a single oral dose of flutamide at different gestational ages. Toxicol Sci. 2005;85:1024–32. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Franca LR, Silva VA, Jr, Chiarini-Garcia H, Garcia SK, Debeljuk L. Cell proliferation and hormonal changes during postnatal development of the testis in the pig. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1629–36. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohler C, Riesenbeck A, Hoffmann B. Age-dependent expression and localization of the progesterone receptor in the boar testis. Reprod Dom Anim. 2007;42:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2006.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cain MP, Kramer SA, Tindall DJ, Husmann DA. Flutamide-induced cryptorchidism in the rat is associated with altered gubernacular morphology. Urology. 1995;46:553–8. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okur H, Muhtaroglu S, Bozkurt A, Kontas O, Kucukaydin N, Kucukaydin M. Effects of prenatal flutamide on testicular development, androgen production and fertility in rats. Urol Int. 2006;76:130–3. doi: 10.1159/000090875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu X, Li H, Liu J-P, Funder JW. Androgen stimulates mitogen-activated protein kinase in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;152:199–206. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sobarzo CM, Lustig L, Ponzio R, Suescun MO, Denduchis B. Effects of di(2-ethylhexyl) phtalate on gap and tight junction protein expression in the testis of prepubertal rats. Microsc Res Tech. 2009;72:868–771. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grazul-Bilska A, Reynolds LP, Redmer DA. Gap junctions in the ovaries. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:947–57. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.5.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lenhart JA, Downey BR, Bagnell CA. Connexin 43 gap junction protein expression during follicular development in the porcine ovary. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:583–90. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.2.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright CS, Becker DL, Lin JS, Warner AE, Hardy K. Stage-specific and differential expression of gap junction in the mouse ovary: connexin-specific roles in follicular regulation. Reproduction. 2001;121:77–88. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Granot I, Dekel N. The ovarian gap junction protein connexin 43: regulation by gonadotropins. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:310–3. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00623-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lui W-Y, Li WM. Molecular mechanisms by which hormones and cytokines regulate cell junction dynamics in the testis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2009;43:43–51. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]