Abstract

Hip resurfacings have been performed in our hospital since May 2001, and in this retrospective study, we analysed the clinical and radiological outcome of the first 144 prostheses (126 patients). One hundred and seven patients have visited our hospital for regular follow-up examination; 16 are not in regular follow-up and were sent a Harris Hip Score (HHS) questionnaire. Three patients live abroad. Mean follow-up was six years. One patient was lost during follow-up. Four prostheses have been revised. The six year cumulative survival rate was 96.7%. Two female patients required revision for aseptic lymphocyte-dominated vascular associated lesions (ALVAL) and two male patients due for femoral head necrosis. Both reoperated female patients had cup inclination >60°. Mean HHS in the follow-up was 95.3, and mean patient satisfaction 2.53 on a scale 0–3. Neck thinning >10% was seen in seven hips and impingement in 12 hips.

Introduction

The idea of hip resurfacing and all-metal bearings was combined successfully by McMinn and Birmingham hip resurfacing (BHR) was introduced in 1997 [1] The results of these second-generation hip resurfacings suggest their outcomes to be comparable with total hip replacements (THRs) but also have aroused some concern regarding short- to medium-term follow-up [2, 3] Hip resurfacing can be recommended as primary treatment for young active patients who have an isolated hip-joint disease and good bone quality of the proximal femur. In women, a young patient is usually considered to be <55 years old and among men <65 years old [2]. In the published hip resurfacing studies, mean patient age is 50–55 years on average [4–8]. Hip resurfacings have been performed in our hospital district since May 2001. We retrospectively studied the results of the first 126 patients (144 hips).

Patients and methods

A total of 126 patients received 144 BHR (Smith and Nephew, Warwick, UK) arthroplasties between May 2001 and May 2003. Patient demographics are described in Table 1. One hundred and seven patients (122 hips) visited our hospital for follow-up examination at least once, and one was lost to follow-up. Both anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the hip and anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis were taken prior to each visit. Clinical outcome was assessed by the Harris Hip Score (HHS). Patient satisfaction was rated on a scale of 0–3 (0 = poor, 1=fair, 2 = good, 3 = excellent). This information was not available at the latest examination for six patients, but their radiographs were available for analysis.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | 82 | 44 |

| Prosthesis | ||

| Left side | 36 | 24 |

| Right side | 36 | 12 |

| Bilateral | 10 | 8 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| OA | 76 | 31 |

| CHD | 8 | 15 |

| Fracture | 0 | 4 |

| Legg-Perthes | 3 | 0 |

| Caput necrosis | 3 | 1 |

| Other | 2 | 1 |

| Mean age (range) | 52.1 (22 to 71) | 50.7 (15 to 68) |

| Preoperation HHS (range) | 52.2 (28 to 83) | 50.7 (24 to 83) |

OA osteoarthritis, CHD congenital hip disease, HHS Harris Hip Score

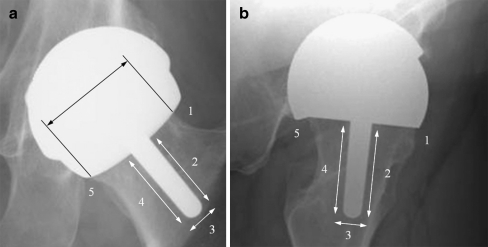

The available radiographs were studied for radiolucency, osteolysis, and heterotopic ossification. Radiolucency and osteolysis around the femoral component were classified as shown in Fig. 1 and on the acetabular side as described by Charnley [9]. Heterotopic ossification (HO) was assessed by the Brooker scale [10]. Any findings indicating impingement were examined and categorised to anterior, cranial or posterior or any combination of these. Stem-shaft angle (SSA) and neck width were also measured. Neck width was determined as indicated in Fig. 1. Neck thinning >10% was considered as significant. Acetabular inclination was calculated against the horizontal line between ischial tuberosities. In case cup shadow overlapped the femoral component, the centre line of the cup opening was assessed, as in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

a) Radiological division of anteroposterior radiograph (AP) and definition of neck width. b) Radiological division of lateral radiograph (Lat)

Fig. 2.

Definition of cup inclination in two different situations

Sixteen patients living outside our hospital district have not been in regular follow-up. A letter consisting of HHS without the motion part was sent to them. Satisfaction and any possible indication for hip revision were also requested. Follow-up radiographs of these patients were not available for analysis. Three patients live abroad. The operations were performed by four different surgeons from our hospital. The posterior approach was used in every case. Simplex antibiotic bone cement (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA) was used to fix the femoral component.

Results

Mean follow-up was six (4.7–7.8) years (Fig. 3). There were 82 men and 44 women in the patient cohort. Four of the 122 hips in regular follow-up have been revised. Fourteen patients approached by letter returned the questionnaire, and one patient were contacted by phone. All 15 patients still had a functioning prosthesis. The cumulative survival rate at a mean of six years was 96.7% [95% confidence interval (CI) 95.0–98.4). Cumulative survival rate at mean six years was 97.7% for men and at mean five years 95.2% for women. Two failures occurred in men and two in women. Information concerning the revised prostheses is shown in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Anteroposterior radiographs of the hip of a 53 year old man: a 2 months postoperatively and b 7.5 years postoperatively, with excellent satisfaction

Table 2.

Revised patients

| Patient | Age | Gender | Time to revision | Aetiology | Operation | New bearings | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 47 | Female | 5.9 years | ALVAL | Cup/stem revision | COC | Pain free |

| 2 | 58 | Male | 3.8 years | Neck fracture due to head necrosis | Stem revision | MOM | Squeaker |

| 3 | 62 | Male | 4.0 years | Malposition due to head necrosis | Stem revision | MOM | Mild pain |

| 4 | 53 | Female | 3.8 years | ALVAL | Cup/stem revision | MOP | Pain free |

ALVAL aseptic lymphocyte-dominated vascular associated lesions. COC ceramic-on-ceramic, MOM metal-on-metal, MOP metal-on-polyethylene

Mean preoperative HHS of the cohort was 55.0 (24–83). In the latest follow-up, HHS was 95.3 (52–100) on average. Preoperatively, the mean range of motion was 120° and in follow-up improved to 242° on average. Paresis of the peroneal nerve on the operated side was diagnosed in two patients, of whom one also had paresis of the femoral nerve. Three prostheses evinced squeaking, of these, two were revised. During the follow-up, no luxation or infection was detected. Nine patients who returned the questionnaire reported to have no pain with a good functional outcome. Five patients experienced pain: three of them considered it mild; one complaining of moderate pain. Overall patient satisfaction was 2.53 on a scale 0–3. Radiological findings are listed in Table 3. Neck thinning >10% was seen in seven patients. Mean SSA was 137°. Mean abduction angle of the acetabular component was 48.0° (35–67°). Mean abduction angle of the cups in the revised group was 55.9°. Abduction angles of the cup in our two ALVAL patients were 64° and 61° (Fig. 4). Two other women had inclination >60°, and both had neck thinning >10%.

Table 3.

Radiological findings

| Number (%) hips | |

|---|---|

| Radiolucency | |

| AP3 | 1 (0.9%) |

| AP5 | 1 (0.9%) |

| Osteolysis | |

| AP1 | 1 |

| AP5 | 1 |

| Lat1 | 2 |

| Lat5 | 3 |

| AP1–AP5 | 1 |

| Lat1–AP1 | 1 |

| Heterotopic ossification | |

| Brooker I | 9 (7.8%) |

| Brooker II | 1 (0.9%) |

| Brooker III | 5 (0.3%) |

| Brooker IV | 1 (0.9%) |

| Impingement | |

| Anterior | 10 (8.7%) |

| Posterior | 1 (0.9%) |

| Anterocranial | 1 (0.9%) |

AP anteroposterior, Lat lateral

Fig. 4.

Anteroposterior radiographs of a 47-year-old woman with cup inclination of 61°: a 2 months postoperatively, b 3.8 years postoperatively, c after revision for to aseptic lymphocyte-dominated vascular associated lesions (ALVAL)

Discussion

The mid-term survival of 96.7% of BHR prosthesis in our study is comparable with survival rates published in other studies in which survival was reported to be between 95.8% and 99.1%, with a mean five to six years [5–8]. Eskelinen et al. reported the results of total hip arthroplasties in patients ≤55 years old for osteoarthritis from the Finnish Arthroplasty register [11]. The seven year cumulative survival rate of 1,893 proximal porous-coated uncemented stems and 1,999 porous-coated press-fit uncemented cups implanted between 1991 and 2001 was 95% for each component separately. Our results were superior compared with these results.

Neck fracture and aseptic loosening of femoral or acetabular component are the most common reasons for failure in hip resurfacings in Australia [2]. Aseptic loosening did not occur among our patients. One male patient sustained late neck fracture after 3.8 years, which in revision was found most likely to be caused by head necrosis. Steffen et al. analysed the prevalence and risk factors of neck fracture among 822 patients (842 hips) [12]. No significant risk factors were found, but a retrieval analysis of 11 fractured hips showed necrosis in nine. All these cases occurred during the first three postoperative months. Surgical technique that damaged the extraosseus blood supply to the femoral head was probably not the cause of failure, which is in accordance with the findings of Steffen et al. [12, 13]. The second head necrosis in our study occurred also in a male patient in whom the femoral component migrated into varus soon after operation, perhaps due to the surgical procedure affecting circulation to the femoral head. However, after appearing to stabilise in that position, revision was necessary only four years after operation. In addition to impairing vascularity of the femoral head, thermal damage is known to be associated with osteonecrosis and femoral head failure [14]. In the study of Campbell et al., thermal osteonecrosis was seen with aseptic loosening of the femoral component [14]. In some of these cases, osteonecrosis healing was seen, which indicates that failure due to osteonecrosis might not necessarily be short term. Acetabular loosening was not observed in our failed resurfacings.

The type of surgical approach used in the resurfacing operation may influence blood supply to the femoral head and hence contribute to prosthesis survival [15]. The posterior approach has been the most popular, and we used it in all our patients. Myers et al. reported no difference in survival between posterior and direct lateral approach with BHR [16]. Beaule et al. studied the influence of the trochanteric slide osteotomy approach in the outcome of hip resurfacing [15]. They reported a reoperation rate 18.3% and do not consider using this approach routinely. Pitto, however, reported results contrary to Beaule et al. and recommends the trochanteric slide osteotomy approach to be used routinely [17].

Only recently have pseudotumours and ALVAL possibly due to hypersenstivity to orthopaedic metals been described as a adverse outcome of cobalt–chromium (CoCr)-bearing surfaces used in hip resurfacings. Great abduction angle is known to lead to wear-related higher metal ion levels, which may lead to pseudotumours [18]. Also in our study, ALVAL patients had significantly higher inclination of the acetabular component compared to unrevised patients. Two men and two women had an inclination angle >60°. They all had HHS 100, but both women had a neck thinning >10%. In the study of Hart et al., hips with unexplained pain had acetabular inclination of 55° on average [22]. The authors did not specify type of prosthesis used. Our study suggests that in BHR, cup inclination >60° is a major risk factor for ALVAL and neck thinning, especially in women. Ollivere et al. described seven ALVAL cases in 463 patients [19]. In another study, the prevalence of pseudotumours was estimated as 1% at five years [20]. In our study, two of the four revised hips had findings strongly indicating ALVAL. In both cases, joint fluid was blood stained, macroscopic metallosis was present and the synovium appeared irritated. The first patient had pain in the groin area. The second patient had a palpable lump in the groin area and diffuse hip pain. Both hips evinced some kind of noise. In summary, both patients presented the most typical symptoms associated with ALVAL and pseudotumours and—notably—both patients were women. The proportion of women in studies pertaining to ALVAL and pseudotumours is 77% (47.4–100%) on average [19–23]. Ollivere et al. determined the risk ratio of female gender for ALVAL as 4.94 (95% CI 1.33–18.31) [19]. Neck thinning >10% was seen seven hips (6.1%). Heilpern et al. and Hing et al. reported prevalence of neck thinning >10% as 14.5% and 27.6%, respectively [5, 24]. The method used by Heilpern et al. for measuring neck thinning differed from ours. They did not specify any factor for neck thinning. Hing et al. reported that valgus position of the femoral component had a significant influence. In our patients with considerable neck thinning, the mean SSA was 134. Our findings indicating impingement were seen in 12 hips (10.4%). Most could be classified as anterior. Clinical significance of impingement still remains unclear. There are no studies clarifying the aetiology and significance of impingement in long-term survival. In a recent study, Ball et al. reported the incidence of posterior femoroacetabular impingement (PFAI) to be 20% among 57 patients (69 hips) [25]. Their findings are quite contrary to ours, with only one case of impingement being posterior. As in our patients with impingement, HHS was between 86 and 100, and patients expressed no complaints. It can therefore be concluded that the clinical relevance of impingement after this follow-up period does not seem to be significant. In the study of Ball et al., no pain was associated with PFAI.

Our results, along with other published studies, show encouraging results for the mid-term survival of BHR. MOM hip resurfacing can still be considered as a good treatment for young patients fulfilling the indications for the operation. Good operative technique avoiding malpositioning of components is crucial. Steep abduction angles of the cup should be avoided, especially in women, among whom the wear-related adverse outcomes appear to be more frequent. Consideration is also advocated when selecting suitable female patients for resurfacing operation. Further investigation is needed regarding the long-term role of asymptomatic femoroacetabular impingement and its relationship with component orientation.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Aleksi Reito, Email: aleksi.reito@uta.fi.

Timo Puolakka, Email: timo.puolakka@coxa.fi.

Jorma Pajamäki, Email: j.pajamaki@coxa.fi.

References

- 1.McMinn D, Daniel J. History and modern concepts in surface replacement. Proc Inst Mech Eng [H] 2006;220:239–251. doi: 10.1243/095441105X68944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimmin A, Beaule PE, Campbell P. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:637–654. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Springer B, Connelly S, Odum S, Fehring T, Griffin W, Mason J, Masonis J. Cementless femoral components in young patients: review and meta-analysis of total hip arthroplasty and hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amstutz HC, Duff MJ. Eleven years of experience with metal-on-metal hybrid hip resurfacing: a review of 1000 conserve plus. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(Suppl 1):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heilpern GN, Shah NN, Fordyce MJ. Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a series of 110 consecutive hips with a minimum five-year clinical and radiological follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:1137–1142. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B9.20524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hing CB, Back DL, Bailey M, Young DA, Dalziel RE, Shimmin AJ. The results of primary Birmingham hip resurfacings at a mean of five years. An independent prospective review of the first 230 hips. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1431–1438. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B11.19336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steffen RT, Pandit HP, Palan J, Beard DJ, Gundle R, McLardy-Smith P, Murray DW, Gill HS. The five-year results of the Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasty: an independent series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:436–441. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.19648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan M, Kuiper JH, Edwards D, Robinson E, Richardson JB. Birmingham hip arthroplasty: five to eight years of prospective multicenter results. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, Riley LH., Jr Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement. Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1629–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLee JG, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop. 1976;121:20–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eskelinen A, Remes V, Helenius I, Pulkkinen P, Nevalainen J, Paavolainen P. Total hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthrosis in younger patients in the Finnish arthroplasty register. 4, 661 primary replacements followed for 0–22 years. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:28–41. doi: 10.1080/00016470510030292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steffen RT, Foguet PR, Krikler SJ, Gundle R, Beard DJ, Murray DW. Femoral neck fractures after hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beaule PE, Campbell P, Lu Z, Leunig-Ganz K, Beck M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Vascularity of the arthritic femoral head and hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 4):85–96. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell P, Beaule PE, Ebramzadeh E, LeDuff M, Smet K, Lu Z, Amstutz HC. A study of implant failure in metal-on-metal surface arthroplasties. Clin Orthop. 2006;453:35–46. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238777.34939.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beaule PE, Shim P, Banga K. Clinical experience of Ganz surgical dislocation approach for metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(Suppl 6):127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers GJ, Morgan D, McBryde CW, O'Dwyer K. Does surgical approach influence component positioning with Birmingham Hip Resurfacing? Int Orthop. 2009;33:59–63. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0469-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitto RP. The trochanter slide osteotomy approach for resurfacing hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2009;33:387–390. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0538-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langton DJ, Sprowson AP, Joyce TJ, Reed M, Carluke I, Partington P, Nargol AV. Blood metal ion concentrations after hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a comparative study of articular surface replacement and Birmingham Hip Resurfacing arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1287–1295. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B10.22308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ollivere B, Darrah C, Barker T, Nolan J, Porteous MJ. Early clinical failure of the Birmingham metal-on-metal hip resurfacing is associated with metallosis and soft-tissue necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1025–1030. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.21701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL, Ostlere S, Athanasou N, Gill HS, Murray DW. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:847–851. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willert HG, Buchhorn GH, Fayyazi A, Flury R, Windler M, Koster G, Lohmann CH. Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints. A clinical and histomorphological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:28–36. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.A.02039pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart AJ, Sabah S, Henckel J, Lewis A, Cobb J, Sampson B, Mitchell A, Skinner JA. The painful metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:738–744. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B6.21682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grammatopolous G, Pandit H, Kwon YM, Gundle R, McLardy-Smith P, Beard DJ, Murray DW, Gill HS. Hip resurfacings revised for inflammatory pseudotumour have a poor outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1019–1024. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.22562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hing CB, Young DA, Dalziel RE, Bailey M, Back DL, Shimmin AJ. Narrowing of the neck in resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: a radiological study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1019–1024. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.18830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ball ST, Schmalzried TP. Posterior femoroacetabular impingement (PFAI) after hip resurfacing arthroplasty. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2009;67:173–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]