Abstract

Purpose

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a leading cause of disability in childhood and early adult life. Clinical and sonographic screening programmes have been used to facilitate early detection but the effectiveness of both screening strategies is unproven. This article discusses the role for screening in DDH and provides an evidence-based review for early management of cases detected by such screening programmes.

Methods

We performed a literature review using the key words ‘hip dysplasia,’ ‘screening,’ ‘ultrasound,’ and ‘treatment.’

Results

The screening method of choice and its effectiveness in DDH still needs to be established although it seems essential that screening tests are performed by trained and competent examiners. There is no level 1 evidence to advise on the role of abduction splinting in DDH although clinicians feel strongly that hip instability does improve with such a treatment regime. The definition of what constitutes a pathological dysplasia and when this requires treatment is also poorly understood.

Conclusion

Further research needs to establish whether early splintage of clinically stable but sonographically dysplastic hips affects future risk of late-presenting dysplasia/dislocation and osteoarthritis. There is a need for high quality studies in the future if these questions are to be answered.

Introduction

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) affects 1–2% of newborns, depending upon whether a clinical or sonographic definition is used [1, 2], and is a leading cause of premature arthritis requiring total hip replacement [3]. Data from the Norwegian arthroplasty register suggest it is responsible for 8.6% of all primary hip replacements and for 28.8% of those in people aged ≤ 60 years [4]. DDH has replaced the term congenital dislocation of the hip (CDH) to reflect more accurately its dynamic presentation and potentially progressive nature [5]. Early diagnosis leads to a more successful outcome [6], but 40 years after the introduction of a national clinical screening programme in the United Kingdom [7], and despite the change in nomenclature and substantial literature on the subject, the number of late cases of DDH is not falling and the operation rate is increasing when it had been expected to decrease [8, 9]. This article discusses the role for screening in DDH and provides an evidence-based review for early management.

DDH is a dynamic disorder

DDH represents a spectrum of neonatal hip joint malformation and instability. In its mildest form acetabular dysplasia is present in the neonatal period, whereby the hip may be stable and concentrically located. It is thought that most cases improve spontaneously and the child may never present clinically, but the number of cases of stable acetabular dysplasia that fail to improve is not known, nor are the implications for hip function and risk of osteoarthritis in later life. The spectrum extends through more severe forms of dysplasia with or without neonatal hip instability, to the established hip subluxation with significant dysplasia, some of which may then go on to dislocate. There are also some cases of a true congenital dislocation at birth where the acetabular dysplasia is minimal. As the child develops, the condition has the potential to improve or worsen which is why some believe ‘late’ dislocation may never be abolished by screening alone [5, 10]. ‘Clinical surveillance’ is the preferred term when discussing diagnosis as repeated assessment throughout infancy is required to improve detection rates [10].

DDH can be classified into three types ‘idiopathic’, teratologic or neuromuscular. Teratologic hip dislocations occur before birth and are associated with syndromes such as arthrogryposis and Larsen’s syndrome. They are characterised by high dislocations that are often stiff; they do not respond well to conservative treatment methods. Neuromuscular conditions such as cerebral palsy and myelomeningocele may also predispose to hip dislocation. Abnormal stresses across the hip joint from altered muscle tone induce dysplastic change in the acetabulum over time and affect hip stability [11]. Neuromuscular dysplasia of the hip generally presents later in childhood with treatment directed at the underlying problem of disordered muscle tone as well as the anatomical dysplasia. This review discusses only ‘idiopathic’ DDH.

Early detection improves outcome

There is general consensus that early detection improves outcome [10, 12]. When detected early the soft tissues are lax. A dislocated hip may be reduced by closed means during the clinical examination. Dynamic flexion-abduction splints such as the Pavlik harness or static splints such as the Von Rosen splint or the Graf splint may stabilise the hip until the soft tissues tighten [13, 14]. With a stable contained hip acetabular dysplasia may subsequently normalise due to the excellent remodelling capacity in the infant. With later detection (over six months), soft tissue contractures and bony deformity on the acetabular or femoral side result in fixed deformities. Closed reduction is less likely to succeed without concomitant soft tissue surgery, usually an adductor tenotomy with or without a psoas tenotomy, and an open surgical reduction may be required. The older the child is at presentation, the more likely it is that an open reduction will be required with the addition of femoral and/or acetabular osteotomies to stabilise the reduction. The outcome of late open reduction is significantly worse in terms of long-term hip function and future risk of osteoarthritis [6]. There is no clear definition as to what constitutes a late diagnosis; however, the success rate of simple conservative treatment falls significantly after seven weeks [15, 16].

The role of screening in DDH

The rationale for screening is to reduce the incidence of late detected DDH, as late diagnosis results in the need for more complex treatments with worse long-term hip function. Early detection enables prompt initiation of abduction splinting and reduces the need for surgical intervention, although epidemiologists believe that this perception has not been proven satisfactorily. The main challenges facing DDH screening relate to its detection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Screening programme ideals and difficulties encountered with developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

| Screening programme ideals | Screening programme difficulties |

|---|---|

| DDH is an important condition | The natural history is poorly understood |

| Screening testsa are safe and acceptable to the patient | Screening testsa lack adequate sensitivity and specificity |

| Treatment and diagnostic facilities are available | Screening testsa cannot be reproduced reliably by all examiners |

| Early detection and treatment in abduction splints improves outcome | There is no universally accepted treatment at different stages of the condition |

| DDH screening is cost effective when performed by trained examiners | There is no recognisable latent and early symptomatic stage |

| Treatment is acceptable to the patient |

a Screening tests refer to clinical examination and ultrasound

Clinical screening

In the United Kingdom, the Standing Medical Advisory Committee (SMAC) has published guidelines on DDH screening that are presently being updated [17]. Currently they state all babies should be screened clinically within 24 hours of birth, prior to hospital discharge, at six weeks, between six and nine months and at walking age.

Clinical screening with the Ortolani [18] manoeuvre (for the reducible dislocation) and Barlow test [19] (for the dislocatable hip) are the most widely used methods to detect DDH in the neonate. These tests have a high specificity (>99%) but low sensitivity (60%), especially with non-trained examiners [20, 21]. In later infancy (over two months of age) limitation of hip abduction has a higher specificity (>95%) but is not sensitive enough (70%) to justify use as a routine screening test [22]. Leg-length discrepancy (Fig. 1) and asymmetric thigh skin folds may also demonstrate hip displacement, but both these signs are unsuitable for screening; asymmetrical thigh skin folds are found in 25% of normal babies [23].

Fig. 1.

Late-presenting developmental dysplasia of the right hip. Galleazi test demonstrates shortening of the right femur. The patient also had limitation of abduction at 90° of hip flexion

Optimism that clinical screening might reduce the rate of late diagnosed DDH has faded [10, 24]. Many reports have failed to demonstrate a reduction and there are even reports of an increased rate of late diagnosis [20, 25]. However when these clinical tests are performed by highly trained examiners, be they paediatricians, surgeons or physiotherapists, there is good evidence that late diagnosis rates can fall to acceptable levels [20, 21]. In the United Kingdom, most clinical screening is performed by poorly trained and inexperienced examiners as part of multiphasic newborn screening. This is thought to be a major factor as to why clinical screening has failed [10, 26].

The future of clinical screening in the United Kingdom

The NHS Newborn and Infant Physical Examination Programme (NIPE) involves a general physical review of the neonate within 72 hours of birth and at six to eight weeks of age. Specific examinations of the child’s heart, eyes, testes and hips are performed. Until last year there was little guidance on the standards and competencies required to perform these assessments. In March 2008 the UK National Screening Committee launched the ‘Newborn Physical Examination Standards and Competencies Programme,’ which aims to ensure all healthcare professionals carrying out such tests are fully trained and competent to do so as part of a wider initiative into improving child health (The NHS Healthy Child Programme) [27]. In addition a national screening management system has been developed and will be implemented throughout the United Kingdom soon. This will provide an interface between primary and secondary care, facilitate accurate assessment and reporting and audit performance. These initiatives, in conjunction with new guidelines from the SMAC, are intended to drive quality and improve outcomes for children with DDH.

Ultrasound screening in DDH

Ultrasound screening can be ‘selective’ for high-risk groups or ‘universal’ for all neonates. The use of ultrasound in the detection of DDH was first proposed by Graf in the 1980s [28]. Since then many different modifications [29, 30] have developed which fall into two main groups: static tests that assess morphology and dynamic tests which assess stability. Ultrasound is best used until 4.5 months of age whilst the femoral head is largely cartilaginous. After this plain antero-posterior pelvic radiographs are more useful.

Static ultrasound methods

The Graf method is the most widely used system throughout Europe (Fig. 2). This static evaluation method assigns hips to one of four groups on the basis of the bony acetabular roof modelling (α-angle), cartilaginous roof (β-angle) and bony rim (Fig. 3) (Table 2). These morphological appearances represent a continuum from normal to severe dysplasia and this has led to variability in sonographic interpretation (Fig. 4). The interobserver and intraobserver error is good for normal hips but poor for borderline and abnormal hips [31]. Graf type 1 hips identified sonographically in the neonatal period are likely to remain normal; however, the natural history of Graf types 2 to 4, with and without intervention, is not fully understood due to the lack of well designed prospective studies with adequate follow-up. International opinion varies on how to treat these differing grades of sonographic dysplasia; some treat Graf 2 hips in abduction splints, whereas others prefer to monitor Graf type 2 hips and only treat types 3 and 4.

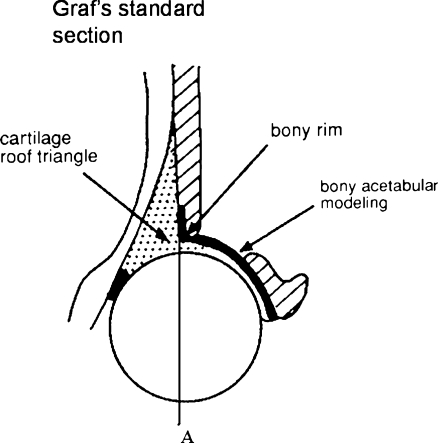

Fig. 2.

Coronal ultrasound section through the acetabulum. Appearances of the acetabular modelling, cartilaginous roof and bony rim grade hip dysplasia into Graf types 1–4 [28]. The femoral head cover method uses line A (an extension of the iliac wing) to define the percentage of the femoral head covered by the bony acetabulum [32]

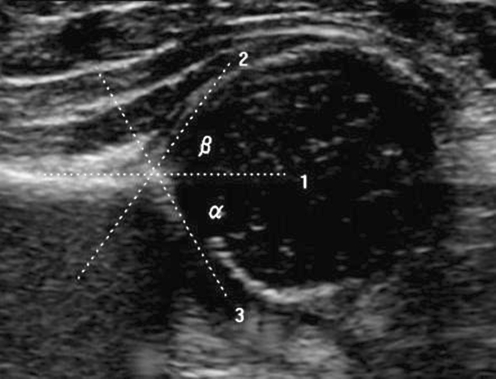

Fig. 3.

Standard coronal ultrasound section through the acetabulum of a normal hip. The α-angle is a measure of acetabular depth and is the angle formed between the acetabular roof (line 3) and vertical cortex of the ilium (line 1). The normal α-angle is ≥ 60°. The beta angle is the angle formed between the vertical cortex of the ilium and triangular labral fibrocartilage (line 2). It represents the acetabular cartilaginous roof modelling and is normally <77°

Table 2.

Relationship of the Graf stage and hip morphology in developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

| Graf classification | Graf angles | Hip morphology |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-angle ≥ 60° | Normal hip; well-formed acetabular cup with femoral head beneath the acetabular roof |

| 2* | 43° ≤ α-angle < 60° | Immature in infants <3 months and mildly dysplastic in infants >3 months; shallow acetabulum with rounded rim. Femoral head concentrically located |

| 2a | 50° ≤ α-angle < 60° | Graf 2a hips demonstrate satisfactory bony modelling with a shallow acetabulum, rounded bony rim and a covering cartilage roof |

| 2b | 43° ≤ α-angle < 60° | Graf 2b and 2c hips demonstrate ossification delay with progressive flattening of the acetabulum |

| 2c | 43° ≤ α-angle ≤49° β-angle <77° | |

| 2d | 43° ≤ α-angle ≤49° β-angle >77° | Type 2d hips demonstrate highly deficient bony modelling with a flattened bony rim, displaced cartilage roof and everted labrum |

| 3 | α-angle <43° | Subluxated hip; very shallow acetabulum with labral eversion and partial displacement of femoral head |

| 4 | Dislocated or dislocatable hip | Dislocated hip; flat acetabular cup and loss of articulation with femoral head. Labral interposition between femoral head and acetabulum |

*Graf type 2 hips are subdivided into types 2a–d

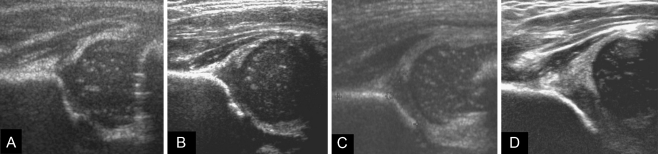

Fig. 4.

Coronal ultrasound sections through the acetabulum using a modified Graf technique [26] illustrate the different Graf subtypes. a Graf 1 normal hip, α-angle ≥ 60°. b Graf 2a mildly dysplastic hip, 50° ≤ α-angle <60°. c Graf 2c severely dysplastic but contained hip with ossification delay and a shallow acetabulum, 43° ≤ α-angle <50°. d Graf 3 subluxed hip, α-angle <43°, β-angle >77° (see Table 2 for morphological descriptions)

Morin has adapted the Graf technique to evaluate the percentage of the femoral head covered by the bony acetabulum – femoral head cover method (Fig. 2) [32]. A hip is considered pathological when femoral head cover by the bony rim of the acetabulum is <44% in girls and <47% in boys [33–35]. Using this diagnostic method, up to 6% of newborns may have dysplastic hips [26]. In contrast to the Graf α-angle, the femoral head cover method requires the hip to be stable. When the hip is unstable, individual measurements can be inaccurate as femoral head cover may vary with eccentric location of the femoral head within the dysplastic acetabulum.

Dynamic ultrasound methods

Dynamic tests popularised by Harcke et al. [30] involve stressing the hip in a manner similar to the Barlow manoeuvre in order to assess stability using real-time ultrasonography. Hips are classified as normal, subluxated or dislocated. Dynamic methods are highly ‘operator dependent,’ as skill in performing the examination in addition to interpreting the images is required. Rosendahl et al. [36] have combined static and dynamic methods to assess hip stability and morphology separately as dynamic tests alone may fail to detect stable hips with acetabular dysplasia.

Although ultrasound has a specificity and sensitivity >90% [37], the subjective nature of the assessment makes reliability and reproducibility difficult to standardise. Ascertainment methods combining static and dynamic measures have the highest sensitivity as they detect stable hips with acetabular dysplasia in addition to morphologically normal hips which prove unstable on stressing [36]. False positive results are common in the first two weeks of life so ultrasound screening should be withheld until two to three weeks after birth to allow physiological instability to improve.

Selective ultrasound screening

Selective ultrasound screening in conjunction with clinical screening is practised in many centres in the United Kingdom. Babies in high risk groups are offered an ultrasound scan on the premise that their hip pathology might go undetected with clinical screening alone. The SMAC guidelines state 60% of dislocations occur in high risk groups [17] with certain risk factors being more predictive than others (Table 3) [38]. Selective programmes screen 1.5–15% of the population and identify unstable hips that would have gone undetected by clinical examination alone [12]. Studies incorporating more risk factors in their inclusion criteria screen more babies; their early detection and abduction splinting rates are higher with a consequent reduction in the requirement for late surgical intervention [9, 12]. However, risk factors are not always a good predictor of DDH. One prospective study showed only one in 75 infants with a risk factor had a dislocated hip, whereas one in 11 infants with clinical instability developed a dislocation [39]. Clinical tests are more accurate than static ultrasound for the diagnosis of instability [40]. This emphasises the need for good clinical examination which is still an essential pre-requisite for selective ultrasound screening programmes.

Table 3.

Risk factors used to inform selective developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) screening policies [38]

| Major | Minor |

|---|---|

| Positive family history in first degree relative | First born |

| Female | |

| Breech presentation | Oligohydramnios |

| Large birthweight for gestational age | |

| Congenital calcaneovalgus foot deformity (1 in 5 risk) (not postural or fixed congenital talipes equinovarus) |

Torticollis |

| Prematurity | |

| Infant positioning in utero and post-natal swaddling |

Universal ultrasound screening

Universal screening of all babies is practised in several countries such as Germany and Austria. These countries have seen a reduction in the number of late diagnosed cases and fewer children require open surgical reduction [41]. One prospective study from Germany reported an ascertainment-adjusted first operative rate of 0.26 per 1,000 live births (95% CI 0.22–0.32) after universal screening [42]. This compared to a UK MRC study which reported a rate of 0.78 (95% CI 0.72–0.84) after clinical screening alone [9]. The results from a universal ultrasound screening programme in Coventry, United Kingdom, are noteworthy [35]. Ninety-eight percent of children (14,050 babies) were screened at birth of which 6% were required to re-attend for further imaging and/or treatment. No late presentation of hip dysplasia was identified in a screened baby. The programme was recently suspended (but subsequently reinstated) over concerns regarding the clinical and cost effectiveness of a universal screening strategy; these issues remain significant barriers to universal screening in many countries.

Clegg et al. [43] argue that costs for clinical, selective and universal screening policies are equal when the costs of running a screening programme are balanced against the expense of treating the condition late. A prospective economic analysis based on a UK randomised control trial concluded that the use of ultrasound in the diagnosis and management of DDH was unlikely to impose an increased cost burden and might reduce costs to health services and families [44].

Universal screening is associated with higher rates of abduction splinting [29] which, if initiated for a condition the child does not have, is an important consideration. Iatrogenic AVN of the femoral head affects up to 1% of treated babies and can predispose to premature osteoarthritis. Femoral nerve palsies and pressure sores also complicate the use of abduction splints. A recent systematic review of the literature by the US Preventative Services Task Force concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend universal ultrasound screening in DDH due to the lack of robust evidence favouring screening [45]. Although we still need to prove that it works, the ethical question of withholding screening for a treatable condition from a group of babies who may develop life-long disability needs careful thought through.

Selective versus universal screening

Two randomised control trials have compared selective to universal ultrasound screening [29, 34]. Holen et al. [34] randomised 15,529 infants to either clinical screening and ultrasound examination of all hips or clinical screening of all hips and ultrasound examination only of those at risk. One late-detected hip dysplasia was seen in the universal group (rate 0.13 per 1,000 babies) compared with six (0.65 per 1,000 babies) in the selective group — a difference that was not statistically significant (p = 0.22). They emphasised the importance of clinical screening performed by well-trained examiners but felt they could not justify universal screening on statistical grounds. Using similar methodology, a study of 11,925 infants by Rosendahl et al. [29] found no statistically significant difference in the incidence of late presenting DDH (including acetabular dysplasia and dislocation) between those managed by clinical examination and those who had an additional ultrasound examination. Again, the clinical screening was performed by highly-trained examiners. In many countries clinical screening is performed by relatively inexperienced examiners. The results in the Holen et al. [34] and Rosendahl et al. [29] studies might have been different had poorly-trained examiners performed the clinical screening, as the advantage offered by ultrasound only becomes evident when such screening is compared with clinical screening by non-trained examiners [46].

Treatment

The primary aim of treatment is to achieve a stable concentric reduction of the femoral head within the acetabulum. The earlier this is achieved, the better the remodelling capacity of the femoral head and acetabulum, correcting any residual dysplasia and lowering the risk of iatrogenic AVN. Most unstable hips stabilise spontaneously by two to six weeks of age without any specific treatment, and >90% of stable acetabular dysplasias develop normally without any treatment within 9–12 weeks [35]. This has led to difficulties in definition as to what constitutes a pathological dysplasia or instability and at what stage this should warrant treatment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Early management for suspected developmental hip dysplasia [26]

* if immediate treatment cannot be instigated at the time of the ultrasound, then the scan should be performed at 4 weeks to allow time for the results to be known and an appropriate referral made.

USS = ultrasound scan

When detected early (six to eight weeks) before significant fixed soft tissue contractures develop, hip reduction and stability is best achieved by the use of a dynamic flexion–abduction orthosis, such as the Pavlik harness, which allows gradual stretching of tight adductor muscles. If Pavlik harness treatment can be instigated within the first three months of life, only 5–10% of infants may require further treatment [13, 47]. When detected later than six to eight weeks, particularly in the presence of instability, static abduction splints such as the Von Rosen splint may be more successful at obtaining and/or maintaining a reduction, although the risk of AVN is higher, particularly in cases of fixed dislocation [48]. Abduction splinting for fixed (unreducible) dislocation must not continue for more than two weeks.

Multiple different abduction splints are available, however there is no level 1 evidence to suggest their clinical effectiveness or safety in the treatment of DDH. In studies instigating treatment at different times and for different grades of dysplasia, rates of reduction with the Pavlik harness vary between 70% and 99% with an AVN rate between 0% and 28% [47, 49, 50]. When analysing the treatment efficacy of abduction splints in the literature it is essential to know the severity of dysplasia being treated and time at which treatment is instigated. Johnson et al. [49] reported a 99% reduction rate with 0% AVN rate when subluxation was included in the definition and harness treatment instigated early. When harness treatment is instigated later and used to treat dislocation as opposed to subluxation or acetabular dysplasia, AVN rates are higher and the success rate is lower [47, 51]. Most studies on abduction splinting are observational and provide level 3 or 4 evidence, which has led to difficulty in knowing what types of dysplasia need treatment and when.

In the United Kingdom and other Northern European countries, mild dysplasias (Graf 2 including subtypes) are generally considered a sign of immaturity not pathology and serial ultrasound monitoring is instigated [34]. Clinical instability or progression of dysplasia to a Graf 3 or 4 hip (subluxed or dislocated) would be an indication for abduction splinting. Many would also consider the presence of persistent instability on ultrasound alone to be an indication for treatment [12]. In the German speaking countries influenced by Graf and colleagues, acetabular dysplasias (Graf 2) are considered pathological and thus treated with splintage. The risk of acetabular dysplasia progressing to dislocation and late osteoarthritis is not yet known; however, they consider this potential risk significant enough to justify placing more babies in abduction splints despite the higher risk of iatrogenic AVN. Pavlik harness treatment is recommended for a maximum of four weeks in America; however, in Europe the treatment time is less well defined.

Early diagnosis and treatment, avoiding the need for surgery, does improve outcome. Angliss et al. [6] reported a 25% rate of osteoarthritis at long-term follow-up after closed reduction as opposed to 49% after open reduction. The success rate of abduction splinting falls significantly if instigated after seven weeks of age, although it may still be used in an infant up until six months [15, 16]. After six months, closed reduction may only be possible with an adductor release, with or without psoas tenotomy, followed by three to four months in an abduction splint. Traction has been advocated to aid closed reduction in late detected DDH with one retrospective study reporting a 95.7% success rate in 36 children between the ages of one and 4.9 years; however, 91.5% of patients subsequently required pelvic osteotomy to correct residual dysplasia [52]. In most cases closed reduction is unlikely to succeed after 18 months and open reduction is necessary. This confers a less successful outcome with high AVN rate, reportedly between 5% and 43% [6, 53, 54]. This variability will reflect the success or failure of previous treatment.

In children of walking age open reduction is frequently combined with a femoral varus derotation osteotomy (VDRO) or pelvic osteotomy. A VDRO redirects the femoral head towards the centre of the acetabulum with the aim of maintaining stability of concentric hip reduction. Acetabular dysplasia may subsequently remodel secondary to the improved containment. However, some clinicians believe the capacity for acetabular remodelling declines rapidly after the age of 18 months and perform pelvic osteotomy at the time of open reduction to correct residual dysplasia directly [55]. A recent two-centre prospective study showed that acetabular remodelling after open hip reduction and pelvic osteotomy was significantly more effective at reversing acetabular dysplasia and maintaining hip reduction than open reduction and femoral VDRO [55]. Residual subluxation and iatrogenic AVN are the most significant predictors of early osteoarthritic change.

Delaying hip reduction until appearance of the femoral head ossific nucleus around the age of six months has been advocated as a treatment strategy to minimise the risk of AVN [56]. A recent moderate evidence meta-analysis including 415 patients from six observational studies showed the presence of the ossific nucleus reduced AVN risk by 60% after closed reduction (relative risk = 0.41, 95% CI 0.18–0.91), but had no significant effect after open reduction (relative risk = 1.14, 95% CI 0.62–2.07) [54]. Planning the time and method of hip reduction in late detected cases remains a controversial subject.

Summary

The screening method of choice and its effectiveness in DDH still needs to be established. If screening was abandoned, late detection rates would increase and a significantly higher risk of AVN would be expected with less successful outcome because open surgical reduction would become more common. Universal ultrasound performed by skilled examiners can eliminate late presenting DDH; however, it does not eliminate surgery as a proportion will still fail conservative treatment. It’s benefit as a screening modality is most significant when the clinical screening is performed by poorly trained examiners as long as the ultrasound screening itself is performed well. At present to reduce late detection rates clinical ‘surveillance’ by well trained examiners should continue throughout infancy. There is no level 1 evidence to advise on the role of abduction splinting in DDH although clinicians feel strongly that hip instability does improve with such a treatment regime. Further research needs to establish whether early splintage of clinically stable but sonographically dysplastic hips affects future risk of late-presenting dysplasia/dislocation and osteoarthritis. On the basis of the available level 3 evidence, Graf 3 or 4 hips and those that are clinically unstable should be splinted early (before seven weeks). Graf 2 hips may be monitored by serial ultrasound and splinted if progression to Graf 3 or 4 dysplasia occurs. Hips which are unstable on ultrasound alone do require treatment.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the British Medical Journal for allowing us to modify tables and figures for use in this article.

References

- 1.Mackenzie IG, Wilson JG. Problems encountered in the early diagnosis and management of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63:38–42. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B1.7204472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn PM, Evans RE, Thearle MJ, Griffiths HE, Witherow PJ. Congenital dislocation of the hip: early and late diagnosis and management compared. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:407–414. doi: 10.1136/adc.60.5.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;213:20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987–99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:579–86. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B4.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klisic PJ. Congenital dislocation of the hip—a misleading term. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:136. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B1.2914985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angliss R, Fujii G, Pickvance E, Wainwright AM, Benson MKD. Surgical treatment of late developmental displacement of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:384–94. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B3.15247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Screening for the detection of congenital dislocation of the hip in infants. London: Dept of Health and Social Security; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanghrajka AP, Murnaghan C, Shekkiris A, Hill RA, Roposch A, Eastwood DM. A consecutive case series review of open reductions for DDH over 5 years: what are the implications for current screening programmes using this proxy measure for failure. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] (suppl) 2009 in press

- 9.Godward S, Dezateux C. Surgery for congenital dislocation of the hip in the UK as a measure of outcome of screening. Lancet. 1998;351:1149–1152. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones D. Neonatal detection of development dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:943–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HT, Wenger DR. Location of acetabular deficiency and associated hip dislocation in neuromuscular hip dysplasia: three dimensional computed topographic analysis. J Paediatr Orthop. 1997;17:143–151. doi: 10.1097/00004694-199703000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eastwood DM. Neonatal hip screening. Lancet. 2003;361:595–597. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walton MJ, Isaacson Z, McMillan D, Hawkes R, Atherton WG. The success of management with the Pavlik harness for developmental dysplasia of the hip using a United Kingdom screening programme and ultrasound-guided supervision. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1013–16. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B7.23513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sluijs JA, Gier L, Verbeke JI, et al. Prolonged treatment with the Pavlik harness in infants with developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:1090–1093. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atalar H, Sayli U, Yavuz OY, Uras I, Dogruel H. Indicators of successful use of the Pavlik harness in infants with developmental dysplasia of the hip. Int Orthop. 2007;31:145–150. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viere RG, Birch JG, Herring JA, Roach JW, Johnston CE. Use of the Pavlik harness in congenital dislocation of the hip. An analysis of failures of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:238–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Screening for the detection of congenital dislocation of the hip. London: Dept of Health and Social Security; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortolani M. The classic. Congenital hip dysplasia in the light of early and very early diagnosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;119:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barlow TG. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1962;44:292–301. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones D. An assessment of the value of examination of the hip in the newborn. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1977;59:318–22. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.59B3.893510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macnicol MF. Results of a 25-year screening programme for neonatal hip instability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:1057–1060. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B6.2246288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jari S, Paton RW, Srinivasan MS. Unilateral limitation of abduction of the hip a valuable clinical sign for DDH? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:104–107. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B1.11418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryder CT, Mellin WG, Caffey J. The infant’s hip—normal or dysplastic? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1962;22:7–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visser F, Sprij AJ, Bos CF. Comment on: clinical examination versus ultrasonography in detecting developmental dysplasia of the hip. Int Orthop. 2009;33:883–884. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0706-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanfridson J, Redlund-Johnell I, Busfield PI. Dislocatable hip and dislocated hip in the newborn infant. BMJ. 1967;4:377–381. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5576.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sewell MD, Rosendahl K, Eastwood DM. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. BMJ. 2009;339:b4454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Screening Committee (2011) NHS Newborn & Infant Physical Examination Screening Programme. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/newborninfantphysical-england. Accessed 5 April 2011

- 28.Graf R. The diagnosis of congenital hip-joint dislocation by the ultrasonic Combound treatment. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1980;97:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00450934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in the neonate: the effect on treatment rate and prevalence of late cases. Pediatrics. 1994;94:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harcke HT, Clarke NM, Lee MS, et al. Examination of the infant hip with real-time ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 1984;3:131–137. doi: 10.7863/jum.1984.3.3.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dias JJ, Thomas IH, Lamont AC, et al. The reliability of ultrasonographic assessment of neonatal hips. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:479–482. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B3.8496227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morin C, Harcke HT, MacEwen GD. The infant hip: real-time US assessment of acetabular development. Radiology. 1985;157:673–677. doi: 10.1148/radiology.157.3.3903854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holen KJ, Tegnander A, Eik-Nes SH, Terjesen T. The use of ultrasound in determining the initiation of treatment in instability of the hip in neonates. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:846–851. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B5.9502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holen KH, Tegnander A, Bredland T, et al. Universal or selective screening of the neonatal hip using ultrasound? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84-B:886–890. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B6.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marks DS, Clegg J, Al-Chalabi AN. Routine ultrasound screening for neonatal hip instability. Can it abolish late-presenting congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76-B:534–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Ultrasound in the early diagnosis of congenital dislocation of the hip: the significance of hip stability versus acetabular morphology. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:430–433. doi: 10.1007/BF02013504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenberg N, Bialik V, Norman D, Blazer S. The importance of combined clinical and sonographic examination of instability of the neonatal hip. Int Orthop. 1998;22(3):185–188. doi: 10.1007/s002640050238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dogruel H, Atalar H, Yavuz OY, Sayli U. Clinical examination versus ultrasonography in detecting developmental dysplasia of the hip. Int Orthop. 2008;32:415–419. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0333-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paton RW, Sriivasan MS, Shah B, et al. Ultrasound screening for hips at risk in developmental dysplasia of the hip: is it worth it? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:255–258. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B2.8972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paton RW. Development dysplasia of the hip: ultrasound screening and treatment. How are they related? Hip Int. 2009;19:S3–8. doi: 10.1177/112070000901906s02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ihme N, Altenhofen L, Kries R, Niethard FU. Hip ultrasound screening in Germany. Results and comparison with other screening procedures. Orthopade. 2008;37(541–6):548–549. doi: 10.1007/s00132-008-1237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kries R, Ihme N, Oberle D, Lorani A, Stark R, Altenhofen L, Niethard FU. Effect of ultrasound screening on the rate of first operative procedure for developmental hip dysplasia in Germany. Lancet. 2003;362:1883–1887. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clegg J, Bache CE, Raut VV. Financial justification for routine ultrasound screening of the neonatal hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:852–857. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B5.9746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gray A, Elbourne D, Dezateux C, et al. Economic evaluation of ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of developmental hip dysplasia in the UK and Ireland. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2472–2479. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.01997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Preventative Services Task Force Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117:898–902. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tegnander A, Terjesen T, Bredland T, Holen KJ. Incidence of late-diagnosed hip dysplasia after different screening methods in newborns. J Paediatr Orthop B. 1994;3:86–88. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199403010-00015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cashman JP, Round J, Taylor G, Clarke NM. The natural history of developmental dysplasia of the hip after early supervised treatment in the Pavlik harness. A prospective, longitudinal follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:418–425. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B3.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bradley J, Wetherill M, Benson MK. Splintage for congenital dislocation of the hip. Is it safe and reliable? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:257–263. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B2.3818757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson AH, Aadalen RJ, Eilers VE, Winter RB. Treatment of congenital hip dislocation and dysplasia with the Pavlik harness. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;155:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujioka F, Terayama K, Sugimoto N, Tanikawa H. Long-term results of congenital dislocation of the hip treated with the Pavlik harness. J Paediatr Orthop. 1995;15:747–752. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199511000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mubarak S, Garfin S, Vance R, et al. Pitfalls in the use of the Pavlik harness for treatment of congenital dysplasia, subluxation, and dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:1239–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rampal V, Sabourin M, Erdeneshoo E, et al. Closed reduction with traction for developmental dysplasia of the hip in children aged between one and five years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:858–863. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morcuende JA, Meyer MD, Dolan LA, Weinstein SL. Long-term outcome after open reduction through an anteromedial approach for congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:810–817. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199706000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roposch A, Stohr KK, Dobson M. The effect of the femoral head ossific nucleus in the treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:911–918. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spence G, Hocking R, Wedge JH, Roposch A. Effect of innominate and femoral varus derotation osteotomy on acetabular development in developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2622–2636. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clarke NM, Jowett AJ, Parker L. The surgical treatment of established congenital dislocation of the hip: results of surgery after planned delayed intervention following appearance of the capital femoral ossific nucleus. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:434–439. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000158003.68918.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]