Abstract

High-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA genes has increased our understanding of microbial community structure, but now even higher-throughput methods to the Illumina scale allow the creation of much larger datasets with more samples and orders-of-magnitude more sequences that swamp current analytic methods. We developed a method capable of handling these larger datasets on the basis of assignment of sequences into an existing taxonomy using a supervised learning approach (taxonomy-supervised analysis). We compared this method with a commonly used clustering approach based on sequence similarity (taxonomy-unsupervised analysis). We sampled 211 different bacterial communities from various habitats and obtained ∼1.3 million 16S rRNA sequences spanning the V4 hypervariable region by pyrosequencing. Both methodologies gave similar ecological conclusions in that β-diversity measures calculated by using these two types of matrices were significantly correlated to each other, as were the ordination configurations and hierarchical clustering dendrograms. In addition, our taxonomy-supervised analyses were also highly correlated with phylogenetic methods, such as UniFrac. The taxonomy-supervised analysis has the advantages that it is not limited by the exhaustive computation required for the alignment and clustering necessary for the taxonomy-unsupervised analysis, is more tolerant of sequencing errors, and allows comparisons when sequences are from different regions of the 16S rRNA gene. With the tremendous expansion in 16S rRNA data acquisition underway, the taxonomy-supervised approach offers the potential to provide more rapid and extensive community comparisons across habitats and samples.

Keywords: taxonomy bin, operational taxonomic unit

The increasing abundance of 16S rRNA gene sequences stimulated by reduced sequencing costs and greatly expanded parallel capacities is providing a more encompassing view of microbial communities (1). Although the short read lengths provided by the current technologies make it more challenging to assign sequences to bacterial taxonomy, the depth and replication provided are powerful advantages (2–4).

Information on bacterial community structure can be compiled in a matrix where different communities are represented as rows and “species” as columns, i.e., a community-by-species matrix. When describing bacterial community relationships based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, each sequence is allocated to a species, usually termed an operational taxonomic unit (OTU), by alignment-based clustering at a specified nucleotide distance, often at a 97% identity. This community-by-OTU matrix, which is based exclusively on nucleotide distances among 16S rRNA gene sequences, has bacterial communities as rows with OTU as columns. This community-by-OTU matrix can be used to measure dissimilarities between bacterial communities (β-diversity) either by presence/absence or abundance data. These dissimilarities combined in a distance matrix can be used for bacterial community comparisons by ordination and clustering methods. This process, termed “taxonomy-unsupervised analysis,” originates from the distribution of 16S rRNA gene sequences into OTUs.

When applying taxonomy-unsupervised analysis to very large numbers of sequences (>106) produced by the new sequencing technologies, much larger computational capacities are required to analyze the data (5). The alignment and clustering of sequences that require calculation of pairwise nucleotide distances is one bottleneck. Even though taxonomy-unsupervised analysis is advantageous in that it includes sequences that are not yet assignable to bacterial taxonomy, the current computational limitations make pursuing comparisons among bacterial communities difficult.

We investigated an alternative analysis, i.e., “taxonomy-supervised analysis,” which consists of allocating sequences into taxonomy-supervised “taxonomy bins” on the basis of the existing bacterial taxonomy, which is rooted in polyphasic taxonomy (6) and hence also reflects physiological, morphological, and genetic information. Currently, several ribosomal RNA databases [i.e., Ribosomal Database Project, RDP (7), Greengenes (8), SILVA (9), and GAST (10)] are dedicated to sequence deposition and provide 16S rRNA gene classification tools.

Here we compared taxonomy-unsupervised (OTU) and taxonomy-supervised analyses for two β-diversity measures, ordination configurations, and hierarchical clustering dendrograms, using ∼1.3 million (M) V4-region 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained by pyrosequencing of 211 bacterial communities. We show that the taxonomy-supervised analysis gives similar ecological conclusions as taxonomy-unsupervised analysis, is more advantageous in avoiding computational limitations, can be used for comparisons with different sequenced regions of the rRNA gene, and has greater tolerance to sequencing errors.

Results

Obtaining V4-16S rRNA Gene Sequences by Barcoded Pyrosequencing.

Regions in the 16S rRNA gene suitable for pyrosequencing were identified, which exhibited: (i) an appropriate amplicon length for pyrosequencing reads, (ii) high coverage by bacterial universal primers, (iii) high resolution and accuracy for bacterial classification and identification, and (iv) a low frequency of insertions and deletions to simplify sequence alignment. Especially, the region used in this study (corresponding to Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene positions 563–802) spanning the hypervariable V4 region, with an average length of 207 bp between primer sequences, is one of the regions with the high classification accuracy using the RDP's naïve Bayesian rRNA classifier (11). Classification accuracy declines with length, but is accurate at higher taxonomic levels even for 50-bp fragments. Its applicability for pyrosequencing was further supported by in silico Unifrac analysis (12). The universality of the primers was determined by internal alignment of perfect matches against 16S rRNA gene sequences in the RDP (94.6% coverage) and from the metagenomic database of the Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling Expedition (94.7% coverage) (13). Specifically, the primers designed in this study targeted an overwhelming majority of known 16S rRNA gene sequences throughout all phyla, while providing deep taxonomic classification useful for community comparisons (Fig. S1).

The ∼1.3 M 16S rRNA gene sequences we used were from 211 bacterial communities from a variety of studies and habitats that reflected a random collection of pyrosequencing project data. Each bacterial assemblage was assigned into 11 habitat groups by a priori classification (a classification made before experimentation) (Table 1), using two-level habitat definitions from the Genomic Standards Consortium's “Habitat-Lite” version 0.4 ontology (14). Detailed sample descriptions are provided in Table S1.

Table 1.

The eleven habitat groups as defined following Habitat-Lite criteria before sampling (sequencing)

| Habitat group | Numbers of samples | Habitat-Lite description |

| G01 | 116 | Terrestrial*, soil† |

| G02 | 8 | Extreme*, soil† |

| G03 | 10 | Terrestrial*, extreme*, soil† |

| G04 | 16 | Organism associated* |

| G05 | 6 | Freshwater*, waste water† |

| G06 | 7 | Freshwater*, sediment† |

| G07 | 2 | Fossil*, organism associated* |

| G08 | 10 | Marine*, sediment† |

| G09 | 14 | Cultured*, soil†, or sediment† |

| G10 | 20 | Extreme*, freshwater*, sediment† |

| G11 | 2 | Extreme*, microbial mat† |

Allocation of 1.3 M 16S rRNA Gene Sequences to Taxonomy Bins and to OTUs at 97% Identity.

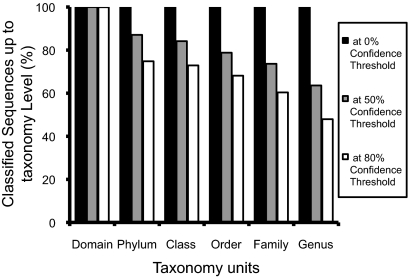

For taxonomy-supervised analysis, each 16S rRNA gene query sequence was assigned to a set of taxonomy bins, 1,400 genera, and 492 artificial “unclassified” taxa, using the RDP classifier (11). When the classifier cutoffs were set at 80, 50, and 0% threshold (the latter forced all sequences into genus bins), 48, 64, and 100% of the sequences were classified to the genus level (Fig. 1), producing 903, 1,170, and 1,259 bins for the respective thresholds. The maximum distance among sequences within each bin increased when the RDP classifier threshold was set lower (Fig. S2). For taxonomy-unsupervised analysis, all sequences clustered into 112,233 OTUs at 97% 16S rRNA gene sequence identity.

Fig. 1.

Qualified sequence classification percentages at different confidence thresholds determined by the RDP classifier for the indicated taxonomic levels.

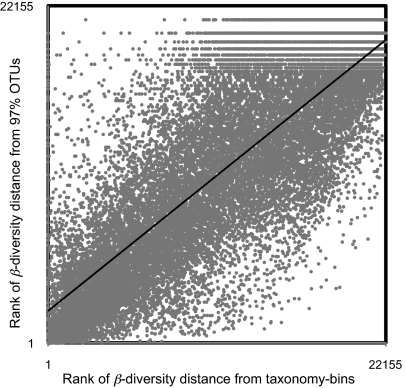

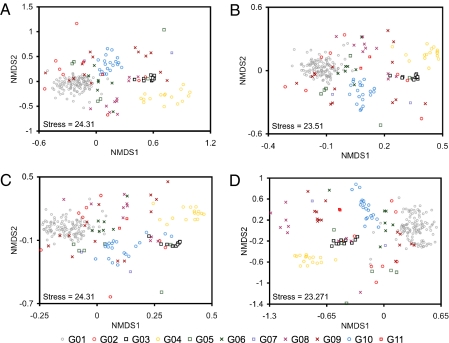

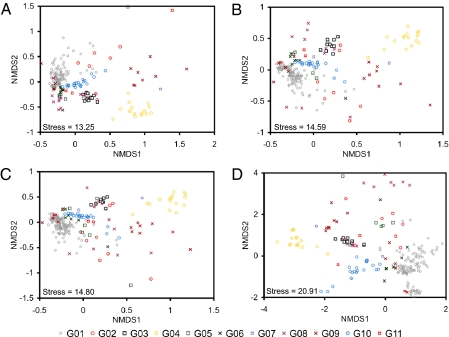

A total of 22,154 pairwise β-diversity calculations using Chao's adjusted Sørensen (15) and Jaccard (16) indices among 211 bacterial communities were performed with both community-by-OTU and community-by-taxonomy bin matrices. The β-diversity distance matrix based on OTUs was highly correlated with those based on taxonomy bins at three different thresholds as confirmed by Mantel tests (Table 2 and Fig. 2; SI Results and Table S2 for 90% OTUs) (17). Ordinations from β-diversity matrices based both on OTU and taxonomy bins were also correlated to each other when configurations two axes of nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) were compared by Procrustes analysis (correlation r > 0.51, P value <0.001) (Figs. 3 and 4 and Table S3). The dendrograms produced by hierarchical clustering (unweighted pair-group method using arithmetric averages, UPGMA) of the matrices on the basis of OTU and taxonomy bins were highly correlated to each other as measured by cophenetic correlation (Table 3). Also, comparisons between a phylogenetic distance matrix created using UniFrac (18) and the β-diversity distance matrix based on taxonomy bins showed these matrices were highly correlated using a Mantel test (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of two distance matrices by Mantel tests

|

r statistic |

||||

| Similarity index used | Taxonomy bins- (at 80%) based distance matrix | Taxonomy bins- (at 50%) based distance matrix | Taxonomy bins- (at 0%) based distance matrix | |

| 97% OTU-based distance matrix | Chao's adjusted | |||

| Sørensen | 0.779*** | 0.803*** | 0.817*** | |

| Jaccard | 0.863*** | 0.860*** | 0.787*** | |

| UniFrac distance matrix | Chao's adjusted | |||

| Sørensen | 0.737*** | 0.732*** | 0.737*** | |

| Jaccard | 0.866*** | 0.873*** | 0.873*** | |

The Mantel statistic was based on Spearman's rank correlation. The correlation r reflects the relationship between two matrices. ***P < 0.001.

The permutations (n = 999) assessed for the significance.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot of β-diversity distance orders (the highest β-diversity is considered as rank 1) calculated using community-by-taxonomy bins matrix (x axis) RDP's classifier at 0% threshold and community-by-OTU matrix (y axis). In this plot, β-diversity distance is 1 − Chao's adjusted Sørensen similarity index.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of NMDS plots based on abundance-based distance (1 − Chao's adjusted Sørensen similarity index). The habitat groups defined by using the ontology of Habitat-Lite are indicated by the different color and shape points (key below). Community-by-taxonomy bins at (A) 80%, (B) 50%, (C) 0%, and (D) community-by-OTU.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of NMDS plots based on occurrence-based distance (1 − Jaccard similarity index). The habitat groups defined by using the ontology of Habitat-Lite are indicated by the different color and shape points (key below). Community-by-taxonomy bins at (A) 80%, (B) 50%, (C) 0%, and (D) community-by-OTU.

Table 3.

Cophenetic correlations of unweighted pair-group method using arithmetric averages (UPGMA) clustering dendrograms

| Cophenetic matrix of UPGMA clustering with |

||||

| Similarity index used | Taxonomy bins- (at 80%) based distance matrix | Taxonomy bins- (at 50%) based distance matrix | Taxonomy bins- (at 0%) based distance matrix | |

| Cophenetic matrix of UPGMA clustering with 97% OTU-based distance matrix | Chao's adjusted | |||

| Sørensen | 0.748 | 0.709 | 0.694 | |

| Jaccard | 0.816 | 0.839 | 0.907 | |

Cophenetic correlation was computed using Spearman's rank from two matrices of cophenetic distance, which is the distance where two samples became the same group in the clustering dendrogram. Higher cophenetic correlation means the UPGMA clustering dendrograms are more similar.

Comparison of Communities with Artificial Sequencing Errors.

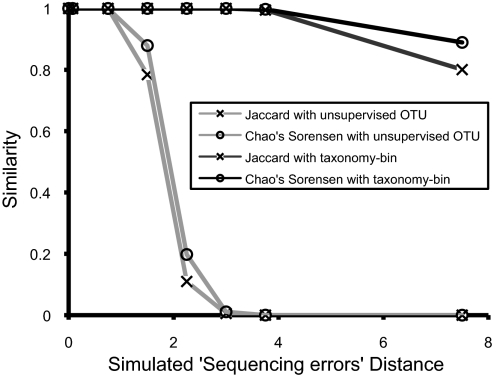

To determine tolerance to sequencing errors, artificial sequencing errors were added to copies of the parent library, consisting of V4 regions extracted from a library of 2,483 near full-length 16S rRNA Sanger-based sequences (19). The resulting altered libraries were compared with the unaltered parent library using Chao's adjusted Sørensen and Jaccard indices after either unsupervised OTUs clustering or taxonomy binning with the RDP classifier. In comparisons using unsupervised OTU clustering, both β-diversity indices dropped to near zero (similar communities have β-diversity indices close to 1) by around 3% added “sequencing errors,” whereas supervised taxonomic binning showed only a small decrease with up to 10% of added sequencing errors (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Simulation of “sequencing errors.” The similarity indices measured the differences between the original parent library and the altered library by simulated sequencing errors distance, mean of the nucleotide substitution rates (%) in all query sequences done in a randomized manner.

Discussion

There are major advantages in the taxonomy-supervised analysis: (i) it is capable of comparing the data coming from different regions in the 16S rRNA gene, (ii) it avoids the computationally intensive alignment and clustering, and (iii) it is easy to combine data sets classified separately. Depending on the length of the 16S rRNA gene region sequenced and the resolution of the bacterial taxonomy classification, the taxonomy-supervised analysis can compare the bacterial communities of 16S rRNA gene sequences spanning other hypervariable regions and bacterial communities with previously deposited sequences. For example, the RDP classifier returned similar classification results for V3, V4, and V6 regions compared with full-length queries at the genus level (Table 4). Therefore, one can obtain comparable data regardless of the sequenced region. When doing such comparisons, one must be aware that primer sets for different regions can sample somewhat different populations.

Table 4.

Bacterial classification accuracy by the RDP classifier of partial sequences spanning hypervariable V3, V4, and V6 regions of 16S rRNA genes

| V3 | V4 | V6 | |||||||

| Bootstrap cutoff, % | 0 | 50 | 80 | 0 | 50 | 80 | 0 | 50 | 80 |

| Human gut | |||||||||

| % classified | 100 | 93.9 | 79.4 | 100 | 92 | 88.4 | 100 | 66.2 | 45.8 |

| % matching | 89.3 | 91.6 | 99.9 | 94.5 | 96.5 | 97.7 | 74.9 | 97.6 | 99.6 |

| Soil | |||||||||

| % classified | 100 | 73.6 | 50.6 | 100 | 76.4 | 56.3 | 100 | 34.4 | 15.6 |

| % matching | 71.9 | 86.8 | 92.9 | 82.7 | 92.7 | 97.3 | 43.8 | 75.6 | 83.1 |

| Marine | |||||||||

| % classified | 100 | 61.4 | 48.3 | 100 | 77.4 | 53.4 | 100 | 52.3 | 41.7 |

| % matching | 66.0 | 94.1 | 99.9 | 81.3 | 96.9 | 98.9 | 49.3 | 88.0 | 93.7 |

| Bovine rumen | |||||||||

| % classified | 100 | 76.3 | 62.3 | 100 | 79.4 | 66.7 | 99.1 | 51.4 | 43.9 |

| % matching | 76.8 | 93.4 | 99.4 | 88.6 | 96.7 | 100 | 55.6 | 88.5 | 89.5 |

RDP classifier used training set no. 6 from March 2010. V3 and V6 regions correspond to those amplified by primers from Dethlefsen et al. (30); V3 region range, E. coli position 358–514 and length 144 ± 11 bp; V6 region range, E. coli position 986–1045 and length 60 ± 4 bp. V4 region corresponds to the amplification product of primers from this paper spanning E. coli position 578–784 and length 207 ± 1 bp. Human gut data were obtained from Dethlefsen et al. (30). Analysis was updated from Claesson et al. (31). Soil data were obtained from Elshahed et al. (32). Marine data were obtained from Walsh et al. (33). Bovine rumen data were obtained from Brulc et al. (34). % classified, fraction of sequences classified to genus level; % matching, matching of each region's classifications with full-length classification.

Another advantage of the taxonomy-supervised analysis is that, due to the fixed number of taxonomy bins, it is simple to add and delete bacterial communities from a preformulated bacterial communities comparison. Using taxonomy-unsupervised analysis, the addition and deletion of bacterial communities affects the community-by-OTU matrix because the number and composition of OTUs are affected by realignment and reclustering. Furthermore, sequence allocation into taxonomy bins is computationally faster than into taxonomy-unsupervised OTUs as the time for the former method increases linearly with the number of sequences, whereas the time for the latter increases quadratically, thus requiring significantly longer processing times. For instance, taxonomy-supervised analysis took 1 h for generating community-by-taxonomy bins using the RDP classifier with 1.3 M sequences (480,000 unique sequences), whereas taxonomy-unsupervised analysis took ∼10 h for sequence alignment using Infernal and 144 h for complete-linkage clustering on an Intel XEON MacPro. Also, the taxonomy-unsupervised analysis is very sensitive to sequencing errors (20–22) (Fig. 5). With taxonomy-supervised analysis, it is statistically very unlikely that random sequencing errors will cause a sequence from one organism to “mutate” to resemble the sequence from an unrelated organism.

We focused on defining the differences between using taxonomy-supervised and taxonomy-unsupervised analyses when comparing bacterial communities. Both β-diversity distance matrices, the configuration of ordinations, and the comparisons of hierarchical clustering results confirmed that the two analyses are significantly correlated such that similar conclusions would be drawn (i.e., Fig. S3, distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA) with both matrices showed the similar correlations with bacterial communities and environmental variable). The resolution, however, is more limited with the taxonomy-supervised analysis due to the coarser average distance among taxa. The median of maximum distance within taxonomy bins was 10.8, 15, and 31.9% at 80, 50, and 0% RDP classifier thresholds, respectively (SI Results and Fig. S2). For example, there was a decreased resolution of habitat group G01 (terrestrial and soil) to other groups in taxonomy-supervised (Fig. 4A) compared with taxonomy-unsupervised analysis (Fig. 4D), especially in occurrence-based NMDS plots. This is due to the more limited number of taxonomy bins in the phylum Acidobacteria (26 genera and four unclassified taxa), Verrucomicrobia (10 genera and eight unclassified taxa), and Gemmatimonadetes (2 genera and five unclassified taxa). These bins have a relatively large number of sequences in habitat group G01 (soils) due to the low number of isolated bacteria or described clusters. In contrast, the communities in habitat group G04 (organism associated; specifically animal feces) were mostly composed of well-characterized groups and exhibited better separation from other groups with the taxonomy-supervised analysis rather than with the taxonomy-unsupervised analysis (Figs. 3 and 4). When a more complete bacterial taxonomy is available for these phyla and the unclassified taxa, the bacterial communities comparison should exhibit a higher resolution, more accurately reflect bacterial community composition, and, if the polyphasic foundation of taxonomy has validity, better reflect the physiologies.

As revolutionary sequencing technologies continue to emerge, generating tremendous numbers of 16S rRNA and other marker gene sequences, the limited flexibility of current clustering tools and the computational requirements will be major bottlenecks. For example, two recent studies have produced millions of 16S amplicon sequences of 150–200 bases in length using Illumina paired-end technology (23, 24). In related work, we have used the technique presented here to analyze 9.7 million paired-end Illumina sequence reads from five soil samples in less than 2 h. The taxonomy-based method has the potential to overcome these limitations as a fast and simple bacterial assemblage comparison method, but its value would be improved if microbiologists advance the taxonomy for the poorly characterized groups.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation.

DNA of 211 bacterial communities was obtained via various extraction methods. Amplicon preparations for pyrosequencing and sequencing 16S rRNA gene by Genome Sequencer FLX system (454 Life Sciences) were performed. The detailed method is described in SI Materials and Methods.

Binning Sequences into Species.

For the taxonomy-unsupervised analysis, the community-by-OTU matrix was generated as follows: briefly, all sequences were aligned by secondary structure using Infernal (25), clustered by complete-linkage clustering, and then allocated into OTUs of 97% nucleotide identity through RDP's pyrosequencing pipeline (26). For the taxonomy-supervised analysis, all sequences were allocated into taxonomy bins of genus and artificial unclassified taxa provided by the RDP classifier at 80, 50, and 0% confidence thresholds (11). The RDP classifier was trained using the Taxonomic Outline of the Bacteria and Archaea (TOBA), release 7.8 (27) augmented with unofficial taxa to cover regions of diversity not covered in the formal bacterial taxonomy. Each of the lowest taxonomy units, i.e., genera and unclassified taxa were considered as taxonomy bins. The reliability of classification of each sequence was estimated by bootstrapping, and sequences that could not be assigned, as they were below a bootstrap confidence threshold, were allocated to an artificial unclassified taxon. In the same manner, the community-by-taxonomy bin matrix was generated with communities as rows and with taxonomy bins as columns.

β-Diversity Measures and Other Statistical Analyses.

β-Diversity measures of the 211 communities were calculated on the basis of pairwise Chao's adjusted Sørensen similarity index (quantitative measures corrected for unseen species) (15) and Jaccard similarity index (presence/absence measures) (16) using EstimateS (http://viceroy.eeb.uconn.edu/EstimateS). Each of the two distance matrices of bacterial communities (1 − Chao's adjusted Sorensen similarity index and 1 − Jaccard similarity index) from the community-by-OTU and community-by-taxonomy bin matrices were compared by Mantel tests (17) on the basis of Spearman's rank correlation ρ. Bacterial communities were displayed by two axes of NMDS to represent the greatest variability. The configuration of the NMDS plots was compared by Procrustes analysis (28), a statistical shape analysis that compares the distribution of points’ shapes with all 211 points in NMDS dimensions. UPGMA hierarchical clustering was performed, and clustering dendrograms were compared by the cophenetic correlation. For measuring UniFrac distance (18), the approximately maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were generated using FastTree (29).

To test bacterial classification variability of the different 16S rRNA gene hypervariable regions, four sets of near full-length (>1,200 bp) 16S rRNA gene sequence collections were used: one each of human gut, soil, bovine rumen, and ocean (30–34). All sequences were aligned and V3, V4, and V6 hypervariable regions extracted on the basis of the reference positions of the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene. Classification results for the full-length sequences were compared with results for the corresponding V3, V4, and V6 hypervariable regions.

To measure the effects of sequencing error on β-diversity measures, the region corresponding to the V4 amplicon region was extracted from a library of 2,483 near full-length 16S rRNA Sanger-based sequences (19) to produce a V4 region high-quality library. Artificial sequencing errors were added to copies of this library by randomly modifying various percentages of bases in each sequence. The original and modified libraries were assigned to supervised taxonomic bins with the RDP classifier as described above. Unsupervised OTU bins were calculated individually for each modified library in combination with the original library as described above.

NMDS, Mantel test, Procrustes analysis, UPGMA clustering, and cophenetic correlation were performed using the R statistical program (R Development Core Team) running the vegan package (Vegan: Community Ecology Package version 1.8-6). Except where otherwise indicated, processing software was written in Java (API v1.5.0) and executed on the Macintosh (OS 10.4) or Linux (2.4.23) operating systems running Java virtual machines from Apple or Sun, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stella Asuming-Brempong, Mary Beth Leigh, David Emerson, Chris Blackwood, Erick Cardenas, Ryan Penton, Blaz Stres, Stephan Gantner, Claudia Etchebehere, Thad Stanton, Debora Rodrigues, Aviaja Hansen, Mathew Marshall, Alexandre Soares Rosado, and Dan Fisher whose projects provided the 211 DNA samples. This study is funded by grants from the Department of Energy, the Department of Agriculture, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, with samples coming from grants from these agencies plus the National Science Foundation, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and several international sources, including the World Class University program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (R33-10076).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1111435108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tringe SG, Hugenholtz P. A renaissance for the pioneering 16S rRNA gene. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sogin ML, et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored “rare biosphere.”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12115–12120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605127103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huber JA, et al. Microbial population structures in the deep marine biosphere. Science. 2007;318:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1146689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roesch LF, et al. Pyrosequencing enumerates and contrasts soil microbial diversity. ISME J. 2007;1:283–290. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamady M, Knight R. Microbial community profiling for human microbiome projects: Tools, techniques, and challenges. Genome Res. 2009;19:1141–1152. doi: 10.1101/gr.085464.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colwell RR. Polyphasic taxonomy of the genus vibrio: Numerical taxonomy of Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and related Vibrio species. J Bacteriol. 1970;104:410–433. doi: 10.1128/jb.104.1.410-433.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole JR, et al. The ribosomal database project (RDP-II): Introducing myRDP space and quality controlled public data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D169–D172. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeSantis TZ, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pruesse E, et al. SILVA: A comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7188–7196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huse SM, et al. Exploring microbial diversity and taxonomy using SSU rRNA hypervariable tag sequencing. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Lozupone C, Hamady M, Bushman FD, Knight R. Short pyrosequencing reads suffice for accurate microbial community analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rusch DB, et al. The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling expedition: Northwest Atlantic through eastern tropical Pacific. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e77. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirschman L, et al. Novo Project. Habitat-Lite: A GSC case study based on free text terms for environmental metadata. OMICS. 2008;12:129–136. doi: 10.1089/omi.2008.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chao A, Chazdon RL, Colwell RK, Shen TJ. Abundance-based similarity indices and their estimation when there are unseen species in samples. Biometrics. 2006;62:361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaccard P. Comparative study of the floral distribution in a portion of the Alps and Jura (Translated from French) Bull Soc Vaud Sci Nat. 1901;37:547–579. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantel N. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res. 1967;27:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: A new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8228–8235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La Duc MT, et al. Comprehensive census of bacteria in clean rooms by using DNA microarray and cloning methods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:6559–6567. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01073-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunin V, Engelbrektson A, Ochman H, Hugenholtz P. Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: Pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:118–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeder J, Knight R. The ‘rare biosphere’: A reality check. Nat Methods. 2009;6:636–637. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0909-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quince C, et al. Accurate determination of microbial diversity from 454 pyrosequencing data. Nat Methods. 2009;6:639–641. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caporaso JG, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartram AK, Lynch MD, Stearns JC, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Neufeld JD. Generation of multimillion-sequence 16S rRNA gene libraries from complex microbial communities by assembling paired-end illumina reads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:3846–3852. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02772-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nawrocki EP, Kolbe DL, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.0: Inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1335–1337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole JR, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: Improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D141–D145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrity GM, et al. Taxonomic Outline of the Bacteria and Archaea (NamesforLife, East Lansing, MI) 2007 Release 7.7, 10.1601/TOBA7.7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peres-Neto PR, Jackson DA. How well do multivariate data sets match? The advantages of a Procrustean superimposition approach over the Mantel test. Oecologia. 2001;129:169–178. doi: 10.1007/s004420100720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: Computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Relman DA. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Claesson MJ, et al. Comparative analysis of pyrosequencing and a phylogenetic microarray for exploring microbial community structures in the human distal intestine. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elshahed MS, et al. Novelty and uniqueness patterns of rare members of the soil biosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5422–5428. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00410-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh DA, et al. Metagenome of a versatile chemolithoautotroph from expanding oceanic dead zones. Science. 2009;326:578–582. doi: 10.1126/science.1175309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brulc JM, et al. Gene-centric metagenomics of the fiber-adherent bovine rumen microbiome reveals forage specific glycoside hydrolases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1948–1953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806191105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.