Abstract

Oxidative stress exacerbates neovascularization (NV) in many disease processes. In this study we investigated the mechanism of that effect. Mice deficient in superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1−/− mice) have increased oxidative stress and show severe ocular NV that is reduced to baseline by antioxidants. Compared with wild-type mice with ischemic retinopathy, Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy had increased expression of several NF-κB–responsive genes, but expression of vascular cell-adhesion molecule-1 (Vcam1) was particularly high. Intraocular injection of anti–VCAM-1 antibody eliminated the excessive ischemia-induced retinal NV. Elements that contributed to oxidative stress-induced worsening of retinal NV that were abrogated by blockade of VCAM-1 included increases in leukostasis, influx of bone marrow-derived cells, and capillary closure. Compared with ischemia alone, ischemia plus oxidative stress resulted in increased expression of several HIF-1–responsive genes caused in part by VCAM-1–induced worsening of nonperfusion and, hence, ischemia, because anti–VCAM-1 significantly reduced the increased expression of all but one of the genes. These data explain why oxidative stress worsens ischemia-induced retinal NV and may be relevant to other neovascular diseases in which oxidative stress has been implicated. The data also suggest that antagonism of VCAM-1 provides a potential therapy to combat worsening of neovascular diseases by oxidative stress.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, reactive oxygen species

Neovascularization (NV) plays a major role in several diseases throughout the body, including cancer, atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and ocular NV. There are some differences in NV occurring in different disease processes and in different tissues, but there are also some common themes. One feature shared by most neovascular processes is that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is an important stimulus and a second is that oxidative stress exacerbates the NV.

Because of these commonalities, the study of ocular NV can provide important general insights regarding disease processes complicated by NV. In addition, the study of ocular NV is important in its own right, because it is the most common cause of visual loss in developed countries. Ocular NV consists of retinal NV, which occurs in diabetic retinopathy and other ischemic retinopathies, and choroidal NV, which occurs in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and other diseases of the Bruch's membrane/retinal pigmented epithelial cell complex. Retinal ischemia is a common feature for all diseases complicated by retinal NV and occurs because of damage to retinal endothelial cells, leading to closure of retinal capillaries and nonperfusion of portions of the retina. Because of lack of oxygen in ischemic retina, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is stabilized, leading to increased levels of HIF-1, which translocates to the nucleus and binds to the hypoxia response element within the promoter region of several genes, thereby increasing their expression (1–3). Although hypoxia has not been clearly established as an important pathogenic feature of AMD or other diseases in which choroidal NV occurs, HIF-1 has been implicated (4).

Several HIF-1–regulated genes, including those that code for VEGF, VEGF-receptor 1 (VEGFR1), stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), CXCR4, platelet-derived growth factor-B (PDGF-B), and erythropoietin (EPO), have been implicated in the pathogenesis of ocular NV and each provides a target for therapeutic intervention (5–12). In fact, intraocular injections of VEGF binding proteins are the current standard of care for neovascular AMD and provide a useful adjunct to scatter photocoagulation for retinal NV and neovascular glaucoma. The best data are available for neovascular AMD in which ranibizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody fragment, causes substantial visual improvement in 34% to 40% of patients (13, 14). Although this finding is impressive compared with past treatments, it is not ideal because many patients do not regain lost vision and a substantial number lose the ability to read and drive. Prevention of neovascular AMD or retinal NV could be a valuable strategy to increase the number of patients who maintain reading and driving vision.

An oral formulation that includes zinc and antioxidants reduces the risk of conversion from the intermediated forms of AMD to advanced forms by about 25% over 7 y (15). Understanding the mechanism of this modest effect could lead to more effective prophylactic treatments. Recently, we have demonstrated that oxidative stress promotes a proangiogenic environment in the eye and contributes to both retinal and choroidal NV (16). In this study, we have explored the mechanism by which oxidative stress exerts this effect.

Results

Expression of Several NF-κB–Regulated Genes Is Increased in Retina by the Combination of Ischemia and Oxidative Stress.

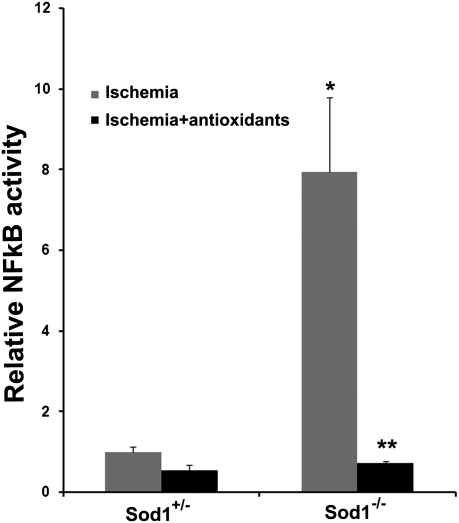

Mice deficient in SOD1 have increased oxidative stress in the retina and in the setting of ischemic retinopathy they develop significantly more retinal NV than wild-type mice (16). In several tissues, NF-κB is activated by oxidative stress and to determine if this is the case in the retina, we measured NF-κB activity in Sod1−/− and Sod1+/− mice with ischemic retinopathy and found it was markedly elevated in the former (Fig. 1). This increase was completely blocked by treatment with antioxidants. We hypothesized that one or more NF-κB–regulated genes may be responsible for the oxidative stress-mediated enhancement of ischemia-induced retinal NV. A microarray was used to screen for NF-κB–regulated genes that are increased by exposure of ischemic retina to excess oxidative stress. Litters containing Sod1−/− and Sod1+/− pups were placed in 75% oxygen at postnatal day (P) 7 and returned to room air at P12, causing ischemic retinopathy, or they were kept in room air so that their retinas were not ischemic. Some of the Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy were treated with antioxidants. Microarrays showed that relative to the other NF-κB-regulated genes on the array, expression of vascular cell-adhesion molecule-1 (Vcam1) was high in ischemic retinas of Sod1+/− mice and in nonischemic retinas of Sod1−/− mice. Compared with the latter, there was an additional threefold increase in ischemic retinas of Sod1−/− mice that was blocked by treatment with antioxidants (Fig. S1A). To better illustrate changes that occurred in other genes, the VCAM-1 data were removed and the data were replotted on a higher scale (Fig. S1B). The result of this was that several genes, including IFN-γ, IL-1α, matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), multidrug resistance transporter (MDR1), fas ligand (FasL), nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), p53, and Myb,showed a substantial increase in ischemic retinas of Sod1−/− mice that was blocked by antioxidants (Fig. 2 B and C). There was no change in expression of β-actin, but GAPDH showed a fourfold increase in expression in ischemic retinas of Sod1−/− mice compared with those of Sod1+/− that was blocked by antioxidants. This finding is consistent with previous reports showing that GAPDH is induced by hypoxia and oxidative stress, including inhibition of SOD1 (17, 18).

Fig. 1.

Oxidative stress combined with ischemia up-regulates NF-κB activity in the retina. Sod1−/− and Sod1+/− pups were placed in 75% oxygen at P7, returned to room air at P12, and treated with antioxidants or vehicle (n = 5 for each group). At P15, NF-κB activity was measured in 10 μg of nuclear protein from each retina. There was a significant increase in NF-κB activity in the ischemic retinas of Sod1−/− vs. Sod1+/− mice (*P < 0.0001 by ANOVA with Dunnett's correction for multiple comparisons) that was completely blocked by antioxidants (**P < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

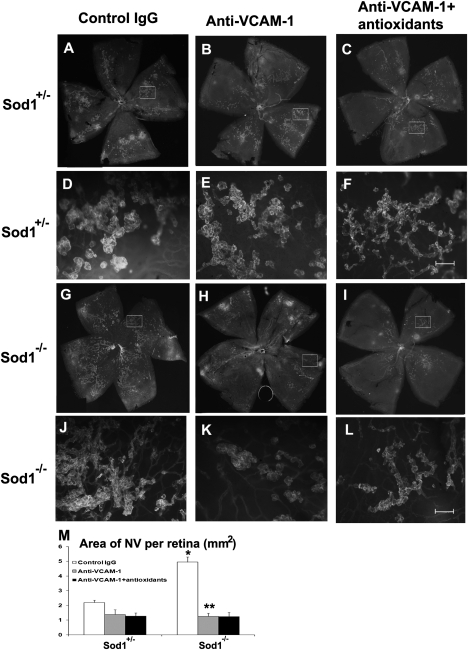

Blockade of VCAM-1 eliminates the oxidative stress-induced increase of retinal NV in ischemic retina. Sod1−/− and Sod1+/− pups with ischemic retinopathy had intraocular injection of 1 μg of rat antimurine VCAM-1 in one eye and 1 μg of rat IgG in the fellow eye. At P17, in vivo immunostaining for PECAM-1, which selectively stains NV on the surface of the retina and hyaloid vessels; the hyaloid vessels are easily distinguished from NV because they are large diameter vessels. Eyes from Sod1+/− mice showed moderate NV on the surface of the retina that was similar in eyes that had been injected with IgG (A and D) or anti–VCAM-1 without (B and E) or with antioxidant treatment (C and F). Eyes from Sod1−/− mice that had been injected with IgG showed extensive NV on the surface of the retina (G and J), but Sod1−/− mice that had been injected with anti–VCAM-1 showed little NV (H and K) that was not further reduced by antioxidants (I and L). The mean (± SEM) area of retinal NV measured by image analysis (M) (n = 6 for each group) was significantly greater in IgG-injected eyes of Sod1−/− vs. Sod1+/− mice with ischemic retinopathy (*P < 0.0001 by ANOVA with Dunnett's correction for multiple comparisons), and also significantly greater (**P < 0.0001) than in anti–VCAM-1–injected eyes of Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy. [Magnification: A–C and G–I, 25× (images were taken at 25× and assembled into single image with Photoshop; D–F and J–L, 200×; Scale bar, 100 μm.]

Real-time PCR was used to independently check the results obtained with microarrays. All of the genes tested, except NOS2, showed a significant increase in expression from the combination of ischemia and oxidative stress compared with ischemia alone, and the increase was blocked by antioxidants (Fig. S1 D–I). These data suggest that there is a general increase in expression of NF-κB–responsive genes by the combination of oxidative stress and ischemia compared with ischemia alone. This finding is consistent with our hypothesis that the increase in ocular neovascularization when oxidative stress is added to ischemia may be caused by one or more NF-κB–responsive genes.

Blockade of VCAM-1 Eliminates the Oxidative Stress-Induced Increase of Retinal NV in Ischemic Retina.

Although some genes showed a higher relative increase than Vcam1 in the setting of excessive oxidative stress and ischemia compared with ischemia alone (Fig. S1C), we were impressed by the high absolute level of expression, as well as the prominent modulation of Vcam1. This finding and its function caused us to focus on VCAM-1 and investigate the effect of blocking it with a neutralizing antibody. In vivo immunostaining for platelet cell adhesion molecule-1 selectively stains NV on the surface of the retina (19), so all dark green staining on retinal whole mounts represents NV and low-power views of entire retinas allow for comparison of amounts of NV. Sod1+/− mice with ischemic retinopathy had moderate amounts of retinal NV on the surface of the retina that was similar in eyes injected with control IgG (Fig. 2A), anti–VCAM-1 (Fig. 2B), or anti–VCAM-1 combined with antioxidant treatment (Fig. 2C). High-power views of boxed areas in Fig. 3 A to C show that the green staining on low-power views represents buds of NV arising from faintly visible underlying retinal vessels (Fig. 3 D–F). Consistent with our previous findings (16), Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy injected with control IgG had substantially more NV (Fig. 2 G and J) than that seen in Sod1+/− mice (Fig. 2A), and it was markedly reduced by injection of anti–VCAM-1 with or without antioxidants (Fig. 2 H–M). Intraocular injection of anti–VCAM-1 essentially completely blocked the increase in retinal NV when excess oxidative stress was combined with ischemia with no added benefit by the addition of antioxidants (Fig. 2M). In an additional experiment, high-magnification images of flat mounts of perfused retinas were assembled into composites and those from Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy injected with control IgG showed extensive NV (Fig. S2), but those from Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy injected with anti–VCAM-1 showed little NV (Fig. S3).

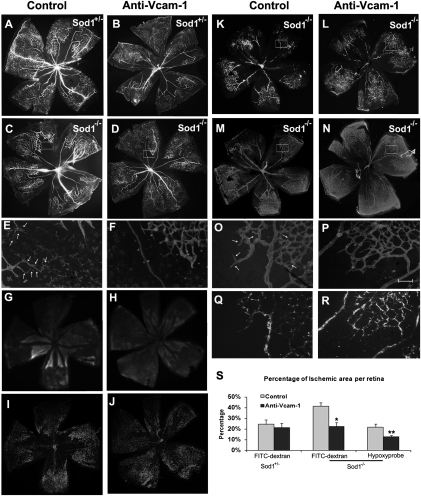

Fig. 3.

The percentage area of nonperfused/hypoxic retina is increased in Sod1−/− mice versus Sod1+/− with ischemic retinopathy and the increase is blocked by anti–VCAM-1 antibody. Sod1−/− and Sod1+/− mice with ischemic retinopathy received an intraocular injection of 1 μg of anti–VCAM-1 in one eye and 1 μg of control IgG or BSA in the fellow eye. At P15, perfusion with FITC-labeled dextran showed that retinas from Sod1+/− mice injected with BSA (A) or anti–VCAM-1 (B) showed similar areas of nonperfusion, but retinas from Sod1−/− injected with BSA (C) or IgG (K) showed much larger areas of nonperfusion than those from eyes injected with anti–VCAM-1 (D and L). (E and F) High magnification of the boxed area at the border of perfused and nonperfused retina in C and D stained with GSA lectin labeled with Alexa594. There are nonperfused vessels (arrows) in the retina of BSA-injected eyes (E) not seen in anti–VCAM-1–injected eyes (F). The retinas of Sod1−/− injected with IgG showed larger areas of staining with hypoxyprobe (G), corresponding to larger areas of nonperfusion (I) compared with those injected with anti–VCAM-1 (H and J). FITC-dextran perfused retinas (K and L) stained for collagen IV (M and N) from P15 Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy showed larger avascular areas in IgG-injected eyes (K and M) than anti–VCAM-1–injected eyes (L and N). High magnification of boxed areas in M and N show nonperfused vascular stuctures in IgG injected eyes (Q vs. O, arrows) but not anti–VCAM-1–injected eyes (R vs. P). Image analysis showed that the mean (± SEM) percentage area of nonperfusion was greater in Sod1−/− mice compared with Sod1+/− mice and was significantly reduced by intraocular injection of anti–VCAM-1 (S) (*P = 0.0044 by ANOVA with Dunnett's correction for multiple comparisons). Furthermore, the mean area of hydroxyprobe-stained retina was significantly greater in Sod1−/− mice injected with control IgG than those injected with anti–VCAM-1 (S, Right) (**P = 0.0119). [Magnification: A–D, G, H, I, J, and K–N, 25× (images were taken at 25× and assembled into a single image with Photoshop); E, F, O, P, Q, and R, 200×; Scale bar, 100 μm.]

Oxidative Stress Increases Both Leukostasis and Influx of CXCR4+ Cells in Ischemic Retina and Both Are Blocked by Anti–VCAM-1 Antibody.

The primary function of VCAM-1 is to enhance adherence of leukocytes to endothelial cells; therefore, we tested the effect of the oxidative stress-induced increase in VCAM-1 in ischemic retina on leukostasis. Compared with Sod1+/− mice with ischemic retinopathy (Fig. S4A), Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy (Fig. S4B) showed many more leukocytes adherent to the walls of retinal vessels and this increase was blocked by intraocular injection of anti–VCAM-1 antibody (Fig. S4 C–E). Adherence to endothelium is a critical first step required for the influx of bone marrow-derived cells into the retina. In ischemic retinopathy, the number of CXCR4+ cells was substantially increased in Sod1−/− mice compared with Sod1+/− mice and the number of CXCR4+ cells was significantly reduced in Sod1−/− mice after an intraocular injection of VCAM-1 antibody (Fig. S4 F–H).

Capillary Nonperfusion Is Increased in Sod1−/− Mice Versus Sod1+/− Mice with Ischemic Retinopathy and the Increase Is Blocked by Anti–VCAM-1 Antibody.

Excessive adherence of leukocytes to the endothelium of retinal capillaries can lead to leukocytic plugging and increased capillary nonperfusion. We measured the area of retinal nonperfusion in Sod1−/− and Sod1+/− mice with ischemic retinopathy at P15. Previously, we measured the area of retinal nonperfusion at P12 immediately after removal of mice from hyperoxia and before the onset of ischemia, and there was no significant difference between Sod1−/− and Sod1+/− mice, indicating that oxidative stress did not exacerbate hyperoxia-induced capillary nonperfusion (16). At P15 after 3 d of ischemia, there was moderate nonperfusion in the retina of Sod1+/− mice that was similar after intraocular injection of anti–VCAM-1 (Fig. 3 A and B), and a substantial increase in nonperfusion in Sod1−/− mice (Fig. 3C) that was reduced by injection of anti–VCAM-1 (Fig. 3 D and S). High magnification of GSA lectin-stained retinas at the perfused/nonperfused junction showed tubular structures in BSA-injected eyes (Fig. 3E, arrows) that were not seen in anti–VCAM-1–injected eyes (Fig. 3F). Hypoxyprobe stains hypoxic retina and the area of hypoxyprobe-stained retina was significantly less (Fig. 3 G, H, and S). There was rough, but not exact correlation between hypoxyprobe staining and nonperfusion (Fig. 3 G–J). Because GSA lectin stains macrophages in addition to endothelial cells, some of the structures in Fig. 3E could represent macrophages. To further compare vessel structure and perfusion status, Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy were injected with control IgG or anti–VCAM-1 at P12, perfused with FITC-labeled dextran at P15, and then retinas were removed and stained for collagen IV. There was better correlation of perfusion and collagen IV staining in anti–VCAM-1–treated eyes compared with those treated with control IgG (Fig. 3 K–R). In the latter, high-power views adjacent to areas where there was no longer any vessel structures remaining, showed collagen IV-lined tubes that were not perfused (Fig. 3O, arrows).

Expression of Several HIF-1–Regulated Genes Is Also Increased in Retina by the Combination of Ischemia and Oxidative Stress.

An increase in the area of capillary nonperfusion in the retina indicates a larger area of ischemic retina, which causes increased levels of HIF-1 and increased expression of genes containing a hypoxia response element (HRE) in their promoter (2, 20). Of six HIF-1–regulated genes examined, all except EPO showed a significant increase in expression when oxidative stress and ischemia were combined, compared with ischemia alone and the increase was blocked by treatment with antioxidants (Fig. S5). Even EPO showed an antioxidant-induced reduction in expression in Sod1−/− retina, and thus there is a general increase in expression of both HIF-1–regulated and NF-κB–regulated genes by the combination of oxidative stress and ischemia compared with ischemia alone. Thus, the increase in ocular NV when oxidative stress is added to ischemia may be caused by up-regulation of both NF-κB–responsive and HIF-1–responsive genes.

Oxidative Stress-Induced Increased Expression of HIF-1–Regulated Genes in Ischemic Retina Is Partially Abrogated by Injection of Anti–VCAM-1 Antibody.

We tested the effect of blocking VCAM-1 on expression of HIF-1–regulated genes. In Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy, intraocular injection of anti–VCAM-1 significantly reduced expression for five of six HIF-1–regulated genes tested (Fig. S6).

Discussion

Stabilization of HIF-1 in ischemic retina resulting in up-regulation of several HIF-1–responsive genes plays a central role in the development of retinal NV (2, 3). When oxidative stress is added to retinal ischemia, there is a substantial increase in the NV (16). In this study, we have investigated the mechanism by which this occurs. Compared with ischemia alone, the combination of ischemia and oxidative stress in the retina resulted in strong stimulation of several NF-κB–modulated genes. The expression of Vcam1 was high in ischemic retina and was increased by the addition of oxidative stress. This finding, combined with the function of VCAM-1, caused us to focus on VCAM-1. Compared with ischemia alone, the combination of ischemia and oxidative stress in the retina resulted in a significant increase in leukostasis and bone marrow-derived cells within the retina, and both were blocked by intraocular injection of an anti–VCAM-1 antibody, as was the enhancement of retinal NV. The addition of excess oxidative stress to ischemia increased capillary nonperfusion and this too was blocked by intraocular injection of an anti–VCAM-1 antibody. Leukostasis can cause or exacerbate capillary nonperfusion, which likely explains why blockade of VCAM-1, which reduces leukostasis, would also reduce capillary nonperfusion. In fact, we found that injection of anti–VCAM-1 antibody in Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy reduced occluded vessels, which explains the smaller areas of nonperfusion; it also reduced the area of hypoxic retina. Thus, the large up-regulation of VCAM-1 in ischemic retina that is exposed to additional oxidative stress appears to have at least two effects that stimulate retinal NV, an increase in retinal ischemia, which causes additional stimulation of HIF-1–responsive genes increasing release of angiogenic factors from retinal cells, and increased retinal levels of bone marrow-derived cells, which also release angiogenic factors (11).

VCAM-1 is an Ig-like adhesion molecule expressed on activated endothelial cells (21); it is not constitutively expressed, but is rapidly induced on blood vessels only after the endothelial cells are stimulated, for example, by proatheroscleotic conditions (22, 23). Antagonists of VCAM-1 inhibited angiogenesis after subcutaneous injection of Matrigel containing fibroblast growth factor-2 or VEGF-A in nude mice (24) and administration of anti–VCAM-1 antibody blocked tubular morphogenesis in vitro induced by IL-4 and IL-13(25). Thus, the newly identified proangiogenic role of VCAM-1 in the retina is consistent with some of its observed activities in other tissues. Although the up-regulation of VCAM-1 and its effects on adhesion and transcytosis of leukocytes appears to be a major factor in the exacerbation of retinal NV by oxidative stress, it is possible that there are other mechanisms, as well such as direct effects on HIF-1. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) are increased by hypoxia and stabilize HIF-1 by reducing the activity of prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) (26–28). In mouse models of cancer, antioxidants suppress tumor growth by reducing HIF-1 levels, probably by blunting hypoxia-induced increases in mitochondrial ROS (29). Conversely, one might anticipate that additional oxidative stress in the presence of hypoxia would further increase mitochondrial ROS and potentially exacerbate hypoxia-induced NV, unless PHDs are maximally inactivated by hypoxia alone. Another potential contributor to the exacerbation of retinal NV by oxidative stress is transcriptional activation of HIF-1α by NF-κB (30). The Hif1α promoter contains a NF-κB binding site and NF-κB family members have been demonstrated to bind to the Hif1α promoter and increase transcription (31, 32). Although it seems likely that these direct effects on HIF-1 might contribute to the increase in retinal NV seen in Sod1−/− mice, our data suggest that increased expression of VCAM-1 plays a major role, because intraocular injection of anti–VCAM-1 essentially eliminated the difference in ischemia-induced retinal NV seen in Sod1−/− mice and Sod1+/− mice. Furthermore anti–VCAM-1 substantially reduced the increased expression of several HIF-1–responsive genes, resulting from the combination of retinal ischemia and oxidative stress compared with ischemia alone, indicating that up-regulation of VCAM-1 contributed to increased HIF-1 transcriptional activity.

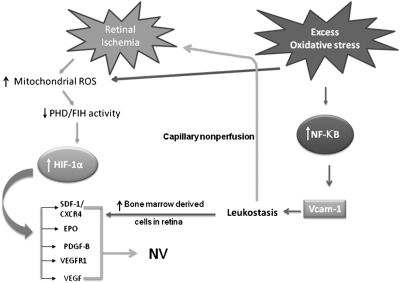

Our data suggest the following model regarding the pathogenesis of retinal NV (Fig. 4). Damage to retinal endothelial cells from various causes (e.g., hyperoxia in retinopathy of prematurity and hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes) results in closure of retinal capillaries and retinal ischemia. Retinal ischemia results in generation of ROS in mitochondria, which reduce the activity of PHD, resulting in increased levels of HIF-1α, increased translocation of HIF-1 to the nucleus, and increased transcription of genes containing a HRE in their promoter, several of which (including Vegf, Vegfr1, angiopoietin-2, Sdf1, and Cxcr4) play critical roles in the sprouting of new vessels in the retina (33). Thus, ischemia-induced oxidative stress participates in stimulation of retinal NV. If the retinal ischemia is accompanied by excessive oxidative stress from another cause, there is up-regulation of NF-κB–regulated genes, particularly VCAM-1. The increase in VCAM-1 increases leukostasis, capillary nonperfusion, and expression of HIF-1–regulated genes, resulting in exacerbation of retinal NV. Of six hypoxia-regulated genes tested, only VEGF was not up-regulated by the addition of excess oxidative stress to ischemia. This finding was tested several times and the results were consistent. Perhaps there are oxidative stress-mediated negative regulatory effects on VEGF that are not exerted on other hypoxia-regulated gene products, which suggests that the exacerbation of ocular NV by oxidative stress is mediated primarily by factors other than VEGF. Although it is not yet understood why this is the case, blockade of VCAM-1 may add value to blockade of VEGF because their effects on ocular NV seem to be independent.

Fig. 4.

Mechanisms by which oxidative stress enhances NV in ischemic retina. Ischemia leads to stabilization of HIF-1 at least in part by generation of ROS that reduce activity of PHD. The stabilized HIF-1 translocates to the nucleus and increases expression of hypoxia-inducible genes, which cause neovascularization. If oxidative stress is added, there is activation of NF-κB, which increases expression several genes but results in particularly high levels of VCAM-1, which promotes leukostasis and influx of bone marrow-derived cells. Leukostasis causes leukocytic plugging, increases capillary nonperfusion, and worsens retinal ischemia, which elevates HIF-1 levels. The further elevation of HIF-1 enhances the already increased expression of HIF-1–responsive genes, which stimulates angiogenesis. Oxidative stress may also increase HIF-1 levels directly by ROS-mediated suppression of PHD. The increase in bone marrow-derived cells in the retina also release VEGF and other factors that further stimulate neovascularization.

The endogenous antioxidant defense system has many components and it is likely that patients vary in the activity of these components and thus their ability to neutralize oxidative stress. Our data suggest that patients with higher levels of oxidative stress are prone to more severe retinal NV in the setting of diabetes and more severe choroidal NV in the setting of AMD. VCAM-1 plays an important role in this increased susceptibility to severe NV and neutralization of VCAM-1 may provide an adjunct to VEGF antagonists for treatment of retinal and choroidal NV. Antioxidants are already used as prophylaxis to reduce the risk of choroidal NV in patients with AMD. If a safe, noninvasive anti–VCAM-1 therapy could be developed, combined use with antioxidants could enhance prophylaxis. In addition, it is important to determine if these mechanisms are at play in other tissues and other neovascular diseases to determine whether anti–VCAM-1 therapy should be considered there as well.

Materials and Methods

Oxygen-Induced Ischemic Retinopathy.

Mice were treated in accordance with the recommendations of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology and the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy was induced in litters of mice containing Sod1−/−, Sod1+/−, and Sod1+/+ pups, as previously described (16). The area of NV on the surface of the retina was visualized by in vivo immunostaining for platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) using rat anti-mouse PECAM-1 antibody (Pharmingen) (19) and measured on retinal flat-mounts image analysis (16).

Measurement of Retinal NF-κB Activity.

Retinas were dissected, homogenized in 50 μL hypotonic buffer, and nuclear extracts were prepared using the Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif). Protein concentration was determined using Bradford method (BioRad) and NF-κB activation was measured in duplicate10-μg samples of nuclear protein with the TransAM NF-κB p65 kit (Active Motif).

cDNA Microarray for NF-κB–Regulated Genes.

A cohort of Sod1−/− mice with ischemic retinopathy was randomly assigned to treatment with an antioxidant mixture previously shown to suppress oxidative damage in the retina, including α-tocopherol (200 mg/kg), ascorbic acid (250 mg/kg), and α-lipoic acid (100 mg/kg) (34). At P15, mice were killed, total retinal RNA was isolated, and 8-μg samples were used for microarray analysis with a mouse NF-κB–regulated cDNA plate array (Signosis), in which each well contained a cDNA probe for 1 of 24 NF-κB–regulated genes. After in situ reverse transcription, hybridization, blocking, and extensive washing, wells were incubated with streptavidin-HRP and chemiluminescence was measured with a microplate reader within 5 min.

Quantitative Real-Rime RT-PCR.

Total retinal RNA was isolated and incubated with reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II; Life Technologies); cDNA and specific primers (Table S1) were used for real-time PCR in a Light Cycler rapid thermal cycler system (Roche Applied Bioscience), as previously described (35). Cyclophilin A was used as a control for normalization and standard curves generated with purified cDNA were used to calculate copy number according to the Roche absolute quantification technique manual. Values are expressed as copies of mRNA of interest per 105 copies of cyclophilin A mRNA.

Blockade of VCAM-1 with Anti–VCAM-1 Antibody.

Litters containing P12 Sod1−/− and Sod1+/− mice with ischemic retinopathy were given a 1-μL intraocular injection of PBS containing 1 μg of azide-free rat anti-mouse VCAM-1 antibody (AbD Serotec), 1 μg of rat IgG (Abcam), or 1 μg of BSA. At P15, RT-PCR was done as described above or the area of nonperfused retina was measured. At P17, remaining mice were used for one of three purposes: measurement of area of retinal NV, measurement of number of bone marrow-derived cells in the retina by in vivo staining for CXCR4 (11), or measurement of leukostasis.

Assessment of Bone Marrow-Derived Cells and Leukostasis.

At P17, mice were given a 1-μL intraocular injection of PE-conjugated anti-CXCR4 antibody (Pharmingen) and rat anti-mouse PECAM-1 antibody. After 8 h, mice were killed and their retinas were removed, fixed in formalin, dissected, and incubated with goat anti-rat secondary antibody conjugated with Alex 488 at 1:500 dilution for 45 min and flat mount.

Leukocytes were labeled with FITC, as previously described (36). Mice were anesthetized at P17, chest cavities were opened, and blood was flushed from the vascular system by infusing PBS through a cannula inserted into the aorta. Blood vessels were fixed by perfusing with 1% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde and 2.5 mL of FITC–labeled Con A (40 μg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4; Vector Laboratories) was infused. Unbound FITC-Con A was removed by thorough perfusion with PBS. Retinas were carefully removed and retinal flat mounts were examined by fluorescence microscopy. Digital images were examined by an investigator masked with respect to genotype and the total number of leukocytes adhering to the retinal vessels was counted.

Measurement of Capillary Nonperfusion.

Mice were perfused with 1 mL of PBS containing 50 mg/mL of fluorescein-labeled dextran (2 × 106 average molecular weight; Sigma-Aldrich). Some retinas were permeabilized, incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-type IV collagen antibody (1:10,000; Cosmo Bio Co.), and then cy3-labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000; Jackson Immunoresearch). Other retinas were stained with Alex594 conjugated isolectin B4 as described (1:500; Invitrogen). Retinal flat mounts were prepared and with the investigator masked with respect to genotype; the area of perfused retina and the total area of the retina were measured by image analysis, as previously described (37).

Measurement of Hypoxic Area of Retina.

At P15, 0.5 μL containing 400 μM of the oxygen-sensitive drug pimonidazole hydrochloride (Hypoxyprobe; HPI Inc.) was injected into the vitreous cavity, and after 90 min mice were killed, retinas were fixed in formalin, and stained with fluorescein-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody against hypoxyprobe (0.02 mg/mL in PBS, 45 min). Retinal flat mounts were examined by fluorescence microscopy and the area of fluorescence per retina was measured by image analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant EY12609 and Core Grant P30EY1765 from the National Eye Institute; P.A.C. is the George S. and Dolores Dore Eccles Professor of Ophthalmology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1012859108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Semenza GL. HIF-1: Mediator of physiological and pathophysiological responses to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1474–1480. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.4.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozaki H, et al. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α is increased in ischemic retina: Temporal and spatial correlation with VEGF expression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly BD, et al. Cell type-specific regulation of angiogenic growth factor gene expression and induction of angiogenesis in nonischemic tissue by a constitutively active form of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Circ Res. 2003;93:1074–1081. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000102937.50486.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinores SA, et al. Implication of the hypoxia response element of the Vegf promoter in mouse models of retinal and choroidal neovascularization, but not retinal vascular development. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:749–758. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aiello LP, et al. Suppression of retinal neovascularization in vivo by inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) using soluble VEGF-receptor chimeric proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10457–10461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okamoto N, et al. Transgenic mice with increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in the retina: A new model of intraretinal and subretinal neovascularization. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:281–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwak N, Okamoto N, Wood JM, Campochiaro PA. VEGF is major stimulator in model of choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3158–3164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo M-S, et al. Photoreceptor-specific expression of platelet-derived growth factor-B results in traction retinal detachment. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64612-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori K, et al. Retina-specific expression of PDGF-B versus PDGF-A: Vascular versus nonvascular proliferative retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2001–2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe D, et al. Erythropoietin as a retinal angiogenic factor in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:782–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lima e Silva R, et al. The SDF-1/CXCR4 ligand/receptor pair is an important contributor to several types of ocular neovascularization. FASEB J. 2007;21:3219–3230. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7359com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, et al. Suppression of retinal neovascularization by erythropoietin siRNA in a mouse model of proliferative retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1329–1335. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenfeld PJ, et al. MARINA Study Group Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown DM, et al. ANCHOR Study Group Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong A, et al. Oxidative stress promotes ocular neovascularization. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:544–552. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graven KK, McDonald RJ, Farber HW. Hypoxic regulation of endothelial glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C347–C355. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.2.C347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito Y, Pagano PJ, Tornheim K, Brecher P, Cohen RA. Oxidative stress increases glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA levels in isolated rabbit aorta. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H81–H87. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen J, et al. In vivo immunostaining demonstrates macrophages associate with growing and regressing vessels. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4335–4341. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida T, et al. Digoxin inhibits retinal ischemia-induced HIF-1alpha expression and ocular neovascularization. FASEB J. 2010;24:1759–1767. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-145664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osborn L, et al. Direct expression cloning of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, a cytokine-induced endothelial protein that binds to lymphocytes. Cell. 1989;59:1203–1211. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien KD, et al. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Implications for the mode of progression of advanced coronary atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:945–951. doi: 10.1172/JCI116670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakashima Y, Raines EW, Plump AS, Breslow JL, Ross R. Upregulation of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 at atherosclerosis-prone sites on the endothelium in the ApoE-deficient mouse. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:842–851. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.5.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garmy-Susini B, et al. Integrin alpha4beta1-VCAM-1-mediated adhesion between endothelial and mural cells is required for blood vessel maturation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1542–1551. doi: 10.1172/JCI23445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukushi J, Ono M, Morikawa W, Iwamoto Y, Kuwano M. The activity of soluble VCAM-1 in angiogenesis stimulated by IL-4 and IL-13. J Immunol. 2000;165:2818–2823. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandel NS, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11715–11720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandel NS, et al. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochodrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: A mechanism of O2 sensing. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25130–25138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu H, et al. Reversible inactivation of HIF-1 prolyl hydroxylases allows cell metabolism to control basal HIF-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41928–41939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao P, et al. HIF-dependent antitumorigenic effect of antioxidants in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rius J, et al. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2008;453:807–811. doi: 10.1038/nature06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belaiba RS, et al. Hypoxia up-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha transcription by involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and nuclear factor kappaB in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4691–4697. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Uden P, Kenneth NS, Rocha S. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by NF-kappaB. Biochem J. 2008;412:477–484. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campochiaro PA. Ocular versus extraocular neovascularization: Mirror images or vague resemblances. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:462–474. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komeima K, Rogers BS, Lu L, Campochiaro PA. Antioxidants reduce cone cell death in a model of retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11300–11305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604056103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen J, et al. Vasohibin is up-regulated by VEGF in the retina and suppresses VEGF receptor 2 and retinal neovascularization. FASEB J. 2006;20:723–725. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5046fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vinores SA, Xiao WH, Shen J, Campochiaro PA. TNF-alpha is critical for ischemia-induced leukostasis, but not retinal neovascularization nor VEGF-induced leakage. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;182:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada H, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor-A-induced retinal gliosis protects against ischemic retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:477–487. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64752-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.