Abstract

The mesoderm of Xenopus laevis arises through an inductive interaction in which signals from the vegetal hemisphere of the embryo act on overlying equatorial cells. One candidate for an endogenous mesoderm-inducing factor is activin, a member of the TGFβ superfamily. Activin is of particular interest because it induces different mesodermal cell types in a concentration-dependent manner, suggesting that it acts as a morphogen. These concentration-dependent effects are exemplified by the response of Xbra, expression of which is induced in ectodermal tissue by low concentrations of activin but not by high concentrations. Xbra therefore offers an excellent paradigm for studying the way in which a morphogen gradient is interpreted in vertebrate embryos. In this paper we examine the trancriptional regulation of Xbra2, a pseudoallele of Xbra that shows an identical response to activin. Our results indicate that 381 bp 5′ of the Xbra2 transcription start site are sufficient to confer responsiveness both to FGF and, in a concentration-dependent manner, to activin. We present evidence that the suppression of Xbra expression at high concentrations of activin is mediated by paired-type homeobox genes such as goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2.

Keywords: Brachyury, Xenopus, mesoderm induction, activin, FGF, thresholds, homeodomain, goosecoid, Mix.1, Xotx2

The mesoderm of Xenopus laevis arises through an inductive interaction in which signals from the vegetal hemisphere of the embryo act on overlying equatorial cells (Sive 1993; Slack 1994). One candidate for an endogenous mesoderm-inducing factor is activin, a member of the TGFβ superfamily (Asashima et al. 1990; Smith et al. 1990; Thomsen et al. 1990; Dyson and Gurdon 1996). Activin is of particular interest because it induces prospective ectodermal tissue to form different mesodermal cell types in a concentration-dependent manner (Green et al. 1992), and recent evidence suggests that it can function in the embryo as a long-range “morphogen” (Gurdon et al. 1994, 1995; Jones et al. 1996; but see Reilly and Melton 1996).

The dose-dependent effects of activin are illustrated by the behavior of Xenopus Brachyury (Xbra). Expression of Xbra is induced in prospective ectodermal tissue as an immediate-early response to activin and to the mesoderm-inducing factor FGF-2 (Smith et al. 1991). Activation of Xbra in response to activin only occurs, however, in a narrow “window” of activin concentrations: Low doses do not induce expression, intermediate concentrations induce high levels, and yet higher concentrations suppress expression (Green et al. 1992; Gurdon et al. 1994, 1995). Because activin may be able to function as a long-range morphogen, these observations suggest a mechanism by which expression of Xbra might be restricted to the marginal zone of the Xenopus embryo. Thus, if activin (or an activin-like molecule) is produced in the vegetal hemisphere of the embryo and is able to diffuse from here toward the animal pole, a gradient of activin activity might be established. The concentrations of activin in vegetal and animal regions would, respectively, be too high or too low for expression of Xbra to occur, but the concentration in the equatorial region might be just right.

Analysis of the response of Xbra to different concentrations of activin provides a powerful tool with which to study the interpretation of a morphogen gradient in vertebrate embryos, but analysis of Xbra expression is also of interest because Brachyury is an important regulatory gene in early vertebrate development. In mouse, chick, zebrafish, and Xenopus embryos, Brachyury is expressed at the onset of gastrulation throughout the nascent mesoderm, and transcripts persist thereafter in notochord and in posterior mesoderm (Herrmann et al. 1990; Smith et al. 1991; Schulte-Merker et al. 1992; Kispert et al. 1995b). Loss of Brachyury function in mouse, zebrafish and Xenopus embryos causes loss of posterior mesoderm and impairment of notochord differentiation (Herrmann et al. 1990; Halpern et al. 1993; Schulte-Merker et al. 1994; Conlon et al. 1996). Brachyury encodes a nuclear sequence-specific DNA-binding protein that functions as a transcription activator (Schulte-Merker et al. 1992; Kispert and Herrmann 1993; Kispert et al. 1995a; Conlon et al. 1996). Widespread expression of Xbra in Xenopus embryos causes ectopic mesoderm formation (Cunliffe and Smith 1992), and the character of the mesoderm formed in such experiments depends on the concentration of Xbra mRNA, the stage at which expression of Xbra begins, and the genes with which it is coexpressed (Cunliffe and Smith 1992, 1994; O’Reilly et al. 1995; Tada et al. 1997). Thus, Brachyury acts as a genetic switch specifying mesodermal fate in embryonic cells, and normal development of the embryo must depend on precise spatial and temporal control of Brachyury expression.

As a first step toward understanding Xbra transcriptional control, we have isolated the promoter region of Xenopus Brachyury. The gene we have cloned appears to be a pseudoallele of Xbra, and we designate it Xbra2. We describe the structure of the 5′-flanking region of Xbra2 and demonstrate that the promoter confers mesoderm-specific responsiveness to linked reporter genes. A reporter construct containing 381 bp of Xbra2 5′-flanking sequence responds to both fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and activin and, like the endogenous gene, is down-regulated by high concentrations of activin. We provide evidence that this down-regulation is attributable to suppression of transcription by homeobox-containing genes such as goosecoid (Cho et al. 1991) and Mix.1 (Rosa 1989), both of which are induced by high concentrations of activin (Green et al. 1992; Gurdon et al. 1994, 1995, 1996), and by Xotx2 (Pannese et al. 1995). Together, these observations provide the first insights into a “threshold” phenomenon in vertebrate embryos.

Results

Isolation of genomic clones encoding the 5′ end of Xenopus Brachyury

Genomic clones containing the first exon of Xenopus Brachyury were obtained as described in Materials and Methods. Clone 3A1 contained ∼2.2 kb of DNA 5′ to the probable translation initiation codon, and comparison with Xbra cDNA revealed that the exon 1/intron 1 boundary is located at codon 67 (Fig. 1). There were significant differences in nucleotide sequence between 3A1 and the original Xbra cDNA (Smith et al. 1991), although they are 99% identical at the amino acid level over the first 67 amino acids. This suggests that 3A1 is derived from a second Xenopus Brachyury gene, which we designate Xbra2. Consistent with this suggestion, the spatial and temporal expression patterns of Xbra2 proved to be indistinguishable from those of Xbra and different from other Xenopus T-box-containing genes (data not shown; see Lustig et al. 1996; Ryan et al. 1996; Stennard et al. 1996; Zhang and King 1996). Furthermore, Xbra2 expression, like that of Xbra, is induced in animal caps by FGF-2 and activin (data not shown).

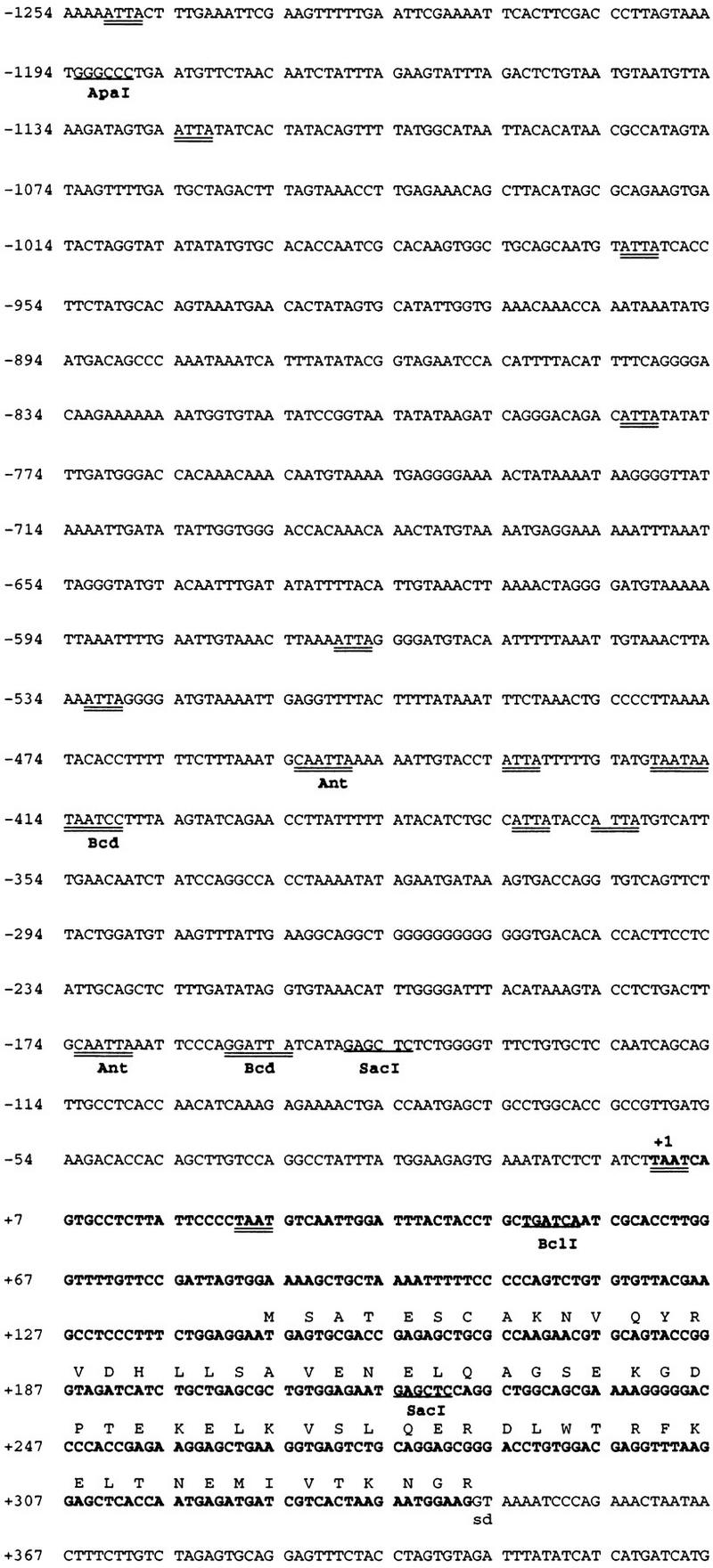

Figure 1.

Sequence of exon 1 of Xbra2 (boldface type) together with 1.2 kb of 5′-flanking sequence. The first 82 bases of intron 1 are also included. Transcription initiation site is indicated by +1 and is also the first nucleotide in boldface type. ATTA sequences are double-underlined, and Antennapedia- and Bicoid-specific sites are marked Ant and Bcd, respectively. This sequence has been submitted to the EMBL database, accession number AJ001528.

DNA (2.1 kb) immediately upstream of the Xbra2 promoter drives mesoderm-specific gene expression in Xenopus embryos

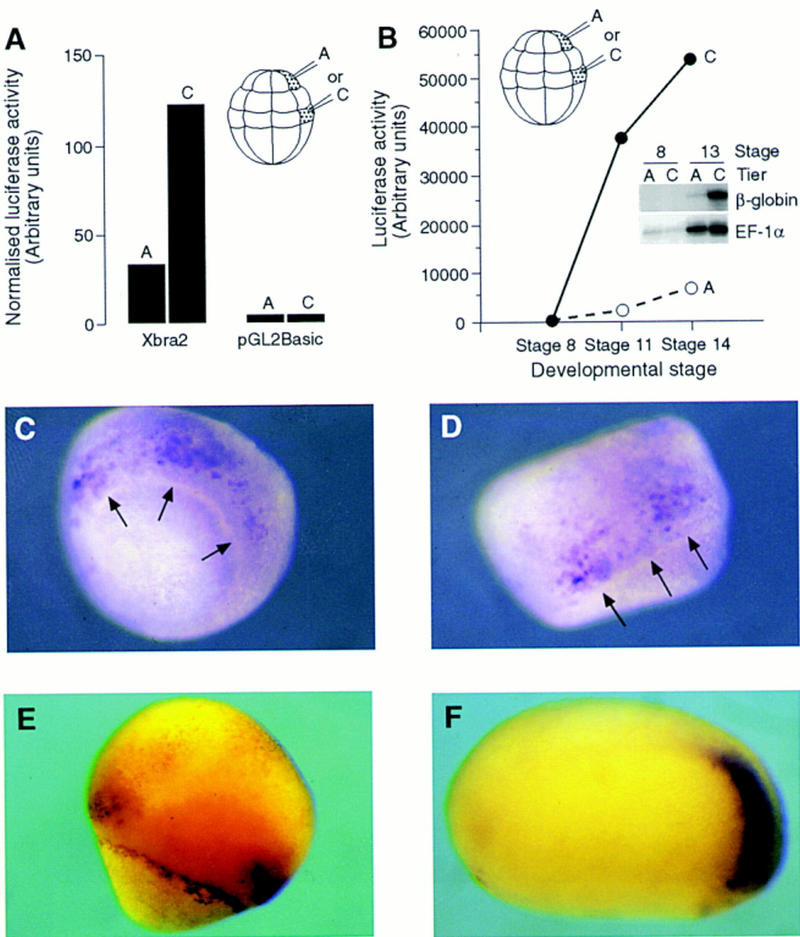

The Xbra2 transcription initiation site was defined using primer extension and is located 144 nucleotides upstream of the initiator methionine codon (data not shown). As a first step in the analysis of Xbra2 regulation, 2.1 kb of Xbra2 5′-flanking sequence and ∼50 bp of 5′-untranslated region were subcloned into the luciferase reporter plasmid pGL2, thus generating Xbra2.pGL2. This construct (or the promoterless vector pGL2Basic) was coinjected with the internal control pSV.β-galactosidase into blastomeres of tier A or tier C of Xenopus embryos at the 32-cell stage. These give rise predominantly to the ectoderm or the mesoderm of the embryo, respectively (Dale and Slack 1987). Injected embryos were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities at gastrula stage 12. The ratio of luciferase to β-galactosidase activity provides a normalized measure of luciferase expression. Figure 2A shows that although injection of the Xbra2 reporter into tier A results in low luciferase activity, extracts of tier C-injected embryos showed high levels. No significant luciferase activity was observed after injection of the promoterless plasmid pGL2Basic. Measurement of luciferase activity at different stages of development (Fig. 2B) showed that reporter gene activity increased dramatically from the mid-blastula stage to the neurula stage. This suggests that sequences within 2.1 kb of 5′-flanking region confer mesoderm-specific and temporally correct transcriptional activity to Xbra2.

Figure 2.

Mesoderm-specific expression of reporter gene constructs containing 2.1 kb of Xbra2 5′-flanking sequence. (A) Xbra2.pGL2 or the promoterless plasmid pGL2Basic was coinjected with pSV.β-galactosidase into a single blastomere of either tier A (prospective ectoderm) or tier C (prospective mesoderm) of 32-cell stage embryos (see inset). Embryos were collected for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity assays at stage 12.5. (B) Luciferase activity in extracts of embryos at stage 8, 11, or 14 injected with Xbra2.pGL2 into a single blastomere of either tier A or tier C at the 32-cell stage. (Inset) RNase protection assay for expression of Xbra2.βg in embryos injected into a single blastomere of tier A or tier C and collected for assay at stage 8 or stage 13. EF-1α was used as a loading control. This experiment has been performed four times, with similar results each time. (C,D) Xbra2.GFP was injected equatorially into all four blastomeres of four-cell stage embryos, and distribution of GFP transcripts at stage 10.5 was determined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Arrows point to the blastopore lip. (E,F) Xbra2.GFP was used to generate transgenic embryos that were analyzed as in C and D at gastrula (E) or tailbud (F; anterior to the left) stage.

To monitor transcripts originating from the Xbra2 promoter directly, we constructed Xbra2.βg, in which 2.1 kb of Xbra2 5′-flanking region was placed upstream of the human β-globin gene, and analyzed levels of β-globin mRNA by RNase protection. Figure 2B (inset) shows that injection of this construct into tier A elicits only weak synthesis of correctly processed transcript, whereas injection into tier C causes strong activation.

The ability of sequences within 2.1 kb of Xbra2 5′-flanking region to drive mesoderm-specific expression was then examined using the construct Xbra2.GFP, in which green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Zernicka-Goetz et al. 1996) was used as a reporter. Xenopus embryos at the four-cell stage were injected in each blastomere with a total of 100 pg of reporter DNA, and GFP activity was visualized by direct observation (not shown) followed by in situ hybridization using a GFP probe. Mosaic GFP expression was seen in prospective mesodermal cells at stage 10.5 (Fig. 2C,D). This expression pattern was specific to Xbra2 flanking sequence, because the promoter of the ubiquitously expressed and constitutively active EF-1α directed widespread mosaic expression (not shown).

To overcome problems associated with mosaic inheritance of injected DNA and to test the ability of the Xbra2 promoter to drive mesoderm-specific expression when integrated into chromatin, we generated transgenic embryos carrying Xbra2.GFP (Fig. 2E,F). At the gastrula stage, most transgenic embryos showed expression of GFP mRNA in a ring around the blastopore, as is seen with the endogenous gene. However, the reporter gene differed from the endogenous gene because the ring was discontinuous, with a gap on the dorsal side (Fig. 2E). This observation is consistent with experiments using the mouse Brachyury promoter, where there are separate elements for primitive streak and notochord expression (Clements et al. 1996). At the tailbud stage, GFP mRNA was normally found in the posterior mesoderm, coincident with endogenous Xbra expression (Fig. 2F); there is no expression of Xbra RNA in the notochord at this stage (Green et al. 1997). Together, these results show that 2.1 kb of Xbra2 5′ sequence is sufficient to direct expression to a large subset of sites where the endogenous gene is expressed; sequences located elsewhere are required for expression in the presumptive notochord.

Sequence within 381 bp of the transcription start site is sufficient to elicit responses to FGF and activin

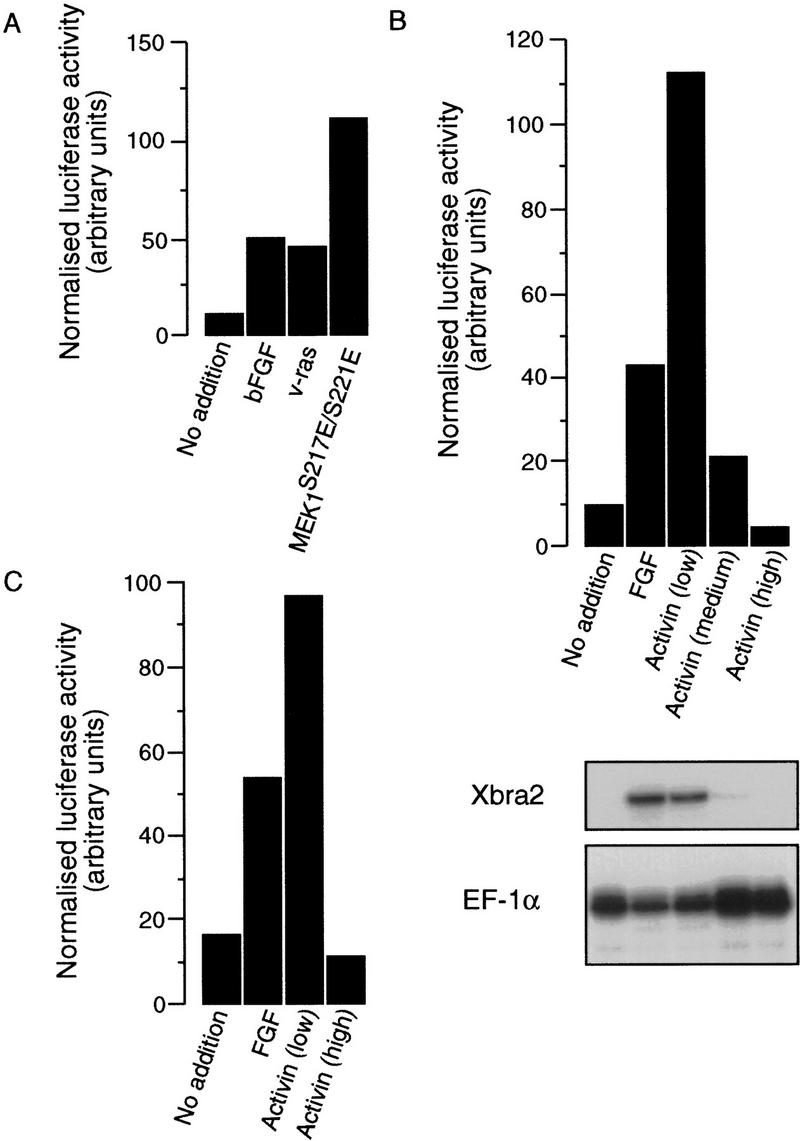

We then tested the ability of FGF, of members of the MAP kinase pathway, and of activin to activate Xbra2.pGL2. The reporter construct was coinjected with a reference plasmid into Xenopus embryos at the one-cell stage. Animal caps were dissected at blastula stages and were incubated in medium containing FGF or activin or were left untreated. Some embryos were also injected with RNA encoding v-Ras or a constitutively active form of MEK1, MEK1S217E/S221E (Umbhauer et al. 1995). Reporter gene activities were analyzed in animal cap extracts at gastrula stage 12.5. FGF caused a strong induction of luciferase activity in animal caps injected with Xbra2.pGL2 (Figs. 3 and 4A,B). In animal caps expressing v-ras or MEK1S217E/S221E, the Xbra2.pGL2 construct was activated in the absence of FGF (Fig. 4A). Neither FGF nor v-Ras caused activation of the promoterless vector pGL2Basic (data not shown). These results suggest that elements mediating FGF-dependent gene activity are located within 2.1 kb of upstream flanking sequence.

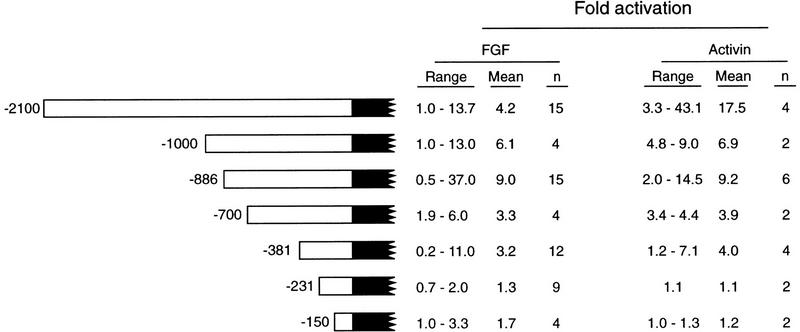

Figure 3.

FGF and activin activate expression of a reporter gene construct containing 2.1 kb of Xbra2 5′-flanking sequence. Sequences upstream of −381 in the Xbra2 5′-flanking sequence are dispensable for response of Xbra2 to FGF (25 ng/ml) and activin. Embryos were injected with the indicated constructs and reference plasmid and, in some cases, with 1 pg of activin mRNA, as described in Materials and Methods. Normalized firefly luciferase activity from stage 12.5 caps is expressed as fold activation over untreated caps. (n) Number of experiments.

Figure 4.

Activation by FGF and components of the MAP kinase pathway of a reporter gene construct containing 2.1 kb of Xbra2 5′-flanking sequence. Activation of the same reporter in response to activin, and of a reporter containing 381 bp of flanking sequence, is dose dependent. (A) Normalized luciferase activity in animal caps injected with Xbra2.pGL2. One group of caps was also injected with v-Ras mRNA, a second with MEK1S217E/S221E, and a third was treated with FGF-2. Analysis was performed at control stage 12.5. This experiment has been performed 3 times with MEK1S217E/S221E alone, 10 times with v-Ras alone, and once with MEK1S217E/S221E and v-Ras in the same experiment. Similar results were obtained each time. (B) Normalized luciferase activity in animal caps treated with FGF-2 or injected with different amounts of activin mRNA (in this experiment “low” represents 1 pg, “medium” represents 5 pg, and “high” represents 50 pg). Analysis was at control stage 12.5. Half of each group of caps was assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities, and the other half was assayed for expression of endogenous Xbra2 by RNase protection. Note that high levels of activin suppress expression of both endogenous Xbra2 and the reporter construct. This experiment has been performed out three times, with similar results each time. (C) A similar experiment to that in B using −381Xbra2.pGL2 (in this experiment “low” represents 1 pg and “high” represents 100 pg activin RNA).

Activin treatment of animal caps also caused expression of the Xbra2.pGL2 reporter construct. These experiments gave variable results, however, and it seemed possible that this was attributable to cells within the animal caps experiencing different concentrations of activin; expression of the endogenous Xbra gene is very sensitive to activin concentration (Green et al. 1992; Gurdon et al. 1994, 1995). In an effort to obtain a more uniform distribution of activin, activin RNA was coinjected with the Xbra2.pGL2 reporter construct and a reference plasmid into the animal hemispheres of Xenopus embryos at the one-cell stage (see Gurdon et al. 1994). When low levels of RNA were injected, strong activation of reporter gene activity was observed (Figs. 3 and 4B).

To identify elements in the Xbra2 promoter responsible for mediating the response to FGF and activin, a deletion series of Xbra2.pGL2 was generated, and constructs were tested for their ability to respond to inducing factors. The degree of induction varied from experiment to experiment, perhaps owing, among other factors, to mosaic expression of the reporter construct (see Discussion). Nevertheless, removal of 5′ sequences down to −381 bp did not prevent induction by FGF and activin, whereas 231 bp was unable to elicit a significant response (Fig. 3).

Examination of Figure 3 suggests that levels of reporter gene activation in response to FGF and activin are higher in constructs containing 2.1 and 1.0 kb of flanking sequence than in those containing only 381 bp. However, the variation in levels of induction observed in different experiments made it difficult to study this issue in a quantitative manner, and the variation also complicated the precise localization of activin or FGF response elements.

The 5′-flanking region of the Xbra2 gene confers dose-dependent responsiveness to activin

The observation that efficient induction of Xbra2.pGL2 is elicited only by low concentrations of activin was reminiscent of the response of the endogenous gene, and this inspired us to examine the phenomenon in detail. Therefore, different amounts of activin RNA were coinjected with the Xbra2.pGL2 reporter construct and a reference plasmid into Xenopus embryos, animal caps were dissected at stage 8, and levels of reporter and of endogenous Xbra2 expression were determined at stage 12.5. Injection of low levels of activin mRNA (1 pg in Fig. 4B) strongly activated Xbra2.pGL2 in animal cap explants, whereas injection of intermediate levels (5 pg) gave much lower activation, and a high concentration (50 pg) reduced luciferase activity to below baseline levels. This dose-response profile mirrored endogenous Xbra2 expression (Fig. 4B). These results show that 2.1 kb of Xbra2 5′-flanking sequence contains elements mediating a dose-dependent response to activin. Further experiments revealed that similar results could be obtained with only 381 bp of Xbra2 flanking sequence (Fig. 4C).

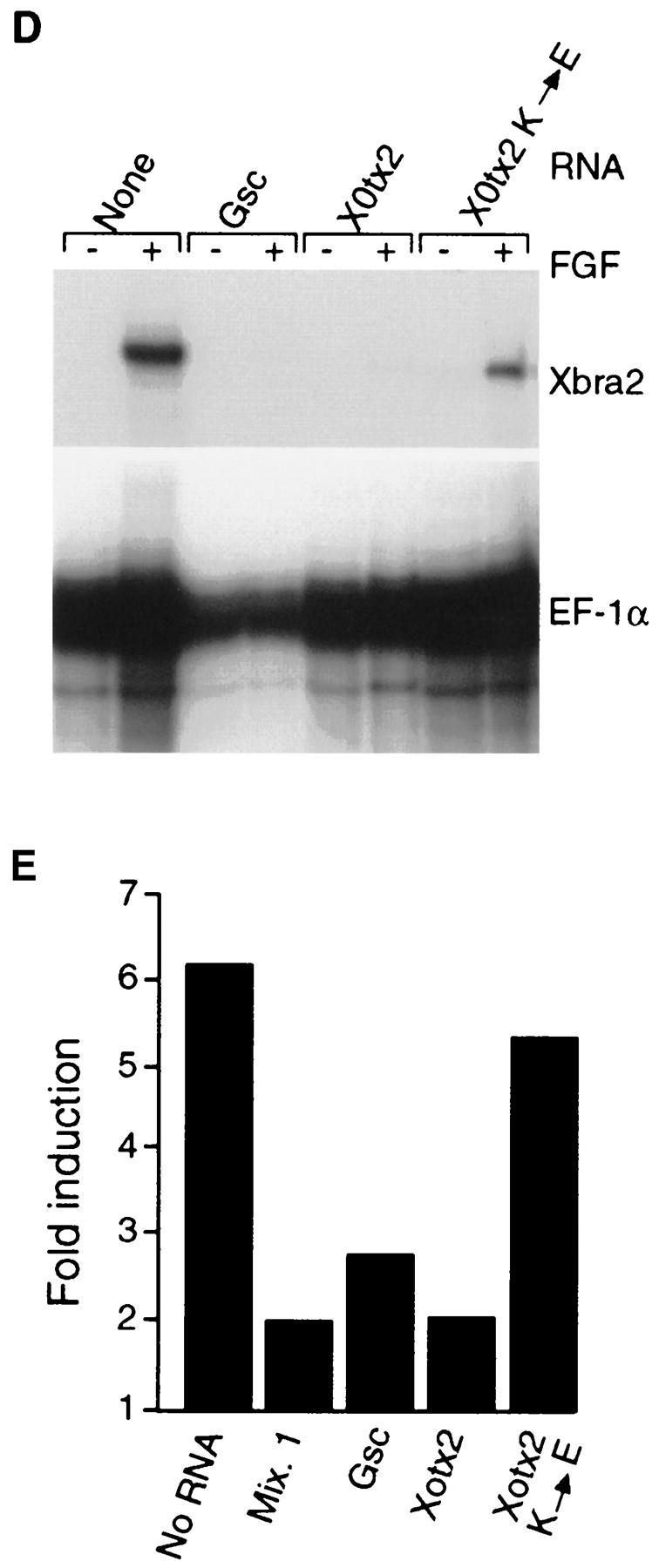

Suppression of Brachyury expression by homeobox-containing genes

High levels of activin cause Xbra2.pGL2 activity to fall to a level below that observed in the absence of activin (Fig. 4B,C), suggesting that Xbra transcription is suppressed actively. Previous work, in which the concentration-dependent induction of Xbra and other genes was studied at different times after activin treatment, identifies two candidate repressors as goosecoid and Mix.1 (Green et al. 1994; see also Artinger et al. 1997). When assayed shortly after activin treatment, levels of Xbra change little as the concentration of activin is raised, whereas expression of both goosecoid and Mix.1 increases dramatically. These genes might therefore be responsible for the subsequent down-regulation of Xbra that occurs at high levels of activin. Additional circumstantial evidence suggesting that goosecoid and Mix.1 may regulate Xbra expression includes the observations that goosecoid functions as a transcriptional repressor (Goriely et al. 1996; Smith and Jaynes 1996) and that under certain circumstances the two proteins can bind DNA cooperatively (Wilson et al. 1993). Goosecoid and Mix.1 both encode paired class homeodomains (Rosa 1989; Blumberg et al. 1991), and another member of this family that is also expressed in the early Xenopus embryo is Xotx2 (Blitz and Cho 1995; Pannese et al. 1995).

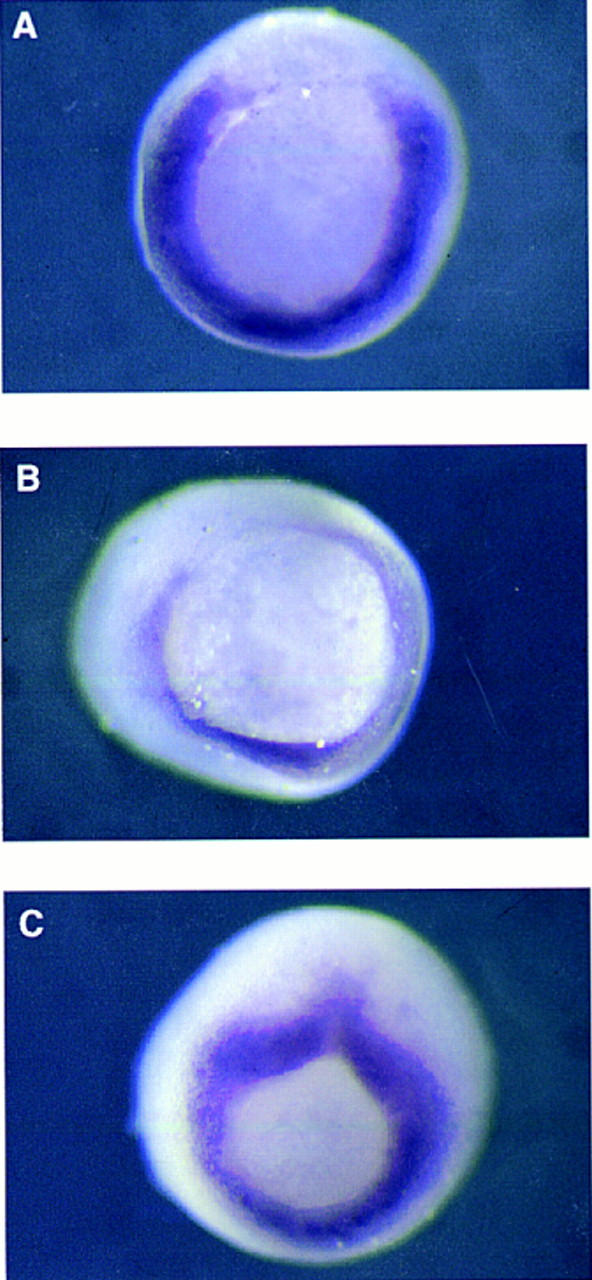

To examine whether goosecoid, Mix.1, or Xotx2 might cause down-regulation of Xbra, Xenopus embryos were injected at the four-cell stage with RNA encoding these proteins, and expression of Xbra and Xbra2 was examined by in situ hybridization at the early gastrula stage. All three gene products caused down-regulation of Xbra expression (see Fig. 5A,B for examples of down-regulation with goosecoid and Xotx2), whereas injection of RNA encoding a mutant version of Xotx2, in which the lysine at position 9 of the recognition helix of the homeodomain is replaced by glutamic acid (Xotx2 K → E), had no effect (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Suppression of Xbra expression in gastrula-stage embryos by paired-type homeodomain proteins. Embryos at the four-cell stage were injected equatorially with 500 pg of goosecoid (A), Xotx2 (B), or Xotx2 K → E (C) RNA in one blastomere, and the expression pattern of Xbra was analyzed by whole-mount in situ hybridization at the early gastrula stage. Note lack of Xbra expression in part of the equatorial region of embryos in A and B. All embryos shown are from the same experiment; that in C is at a slightly later stage than those in A and B. (D) Suppression of FGF-induced Xbra2 mRNA in animal caps by goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2 but not by Xotx2 K → E. Embryos at the one-cell stage were injected with 1 ng of the indicated RNAs, and animal caps were cut at stage 8 and incubated in FGF until stage 12. Xbra2 and EF-1α transcripts were detected by RNase protection. Note that FGF-induced expression of Xbra2 is strongly inhibited by goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2 but not by Xotx2 K → E. (E) Suppression of FGF-induced Xbra2.pGL2 luciferase activity in animal caps by goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2 but not by Xotx2 K → E. Embryos were coinjected with 1 ng of the indicated RNAs, 30 pg of Xbra2.pGL2, and 10 pg of pRL–SV reference plasmid. Animal caps were excised at stage 8 and incubated with FGF until stage 12.5, and firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined. Activity of Xbra2.pGL2 is presented as fold activation over uninduced levels. This experiment was repeated twice for all four RNAs and four additional times with goosecoid, with similar results.

Suppression of Xbra2 expression by goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2 was also revealed in experiments in which animal pole explants derived from injected embryos were treated with FGF. Expression of Xbra2 in response to FGF was strongly down-regulated by all three proteins but not by the control construct Xotx2 K → E (Fig. 5D); similar results were seen when activin was used instead of FGF (not shown). The effects of goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2 were specific, because activation of Pintallavis (Ruiz i Altaba and Jessell 1992) was not affected (not shown).

We then studied the ability of goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2 to suppress FGF-induced activity of the Xbra2.pGL2 reporter in animal pole explants. The presence of all three gene products caused a general reduction in Xbra2.pGL2 reporter activity in such caps (not shown), and as illustrated in Figure 5E, overexpression of goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2, but not of Xotx2 K → E, caused a reduction in FGF-induced reporter activity, suggesting that these transcription factors modulate Xbra2 expression by suppressing its transcriptional activity. Similar results were seen when animal pole explants were treated with activin (not shown).

Goosecoid, Xotx2, and Mix.1 bind to sequences within the 5′-flanking region of Xbra2

The suppression of Xbra2 transcription by goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2 may occur indirectly through activation of downstream repressors or directly, by binding to sites in the Xbra2 regulatory region. Most homeodomain-containing proteins bind to sequences containing a TAAT core (Treisman et al. 1992), and there are four such motifs within the 381 bp of Xbra2 flanking sequence that confers suppression of reporter gene expression in response to high levels of activin (Fig. 1). One of these motifs, GGATTA, matches the consensus binding site of the Drosophila morphogen Bicoid, to which goosecoid also binds (Blumberg et al. 1991; Wilson et al. 1993). Recognition of the GG dinucleotide 5′ of the ATTA motif is specified by lysine at position 50 of the homeodomain, a residue also present in Otx2. Another site present in the Xbra2 5′-flanking region, CAATTAA, conforms to the consensus for the Antennapedia class of homeobox proteins, which have glutamine at position 50 of the homeodomain (Desplan et al. 1988; Hanes and Brent 1991): Mix.1 belongs to this class.

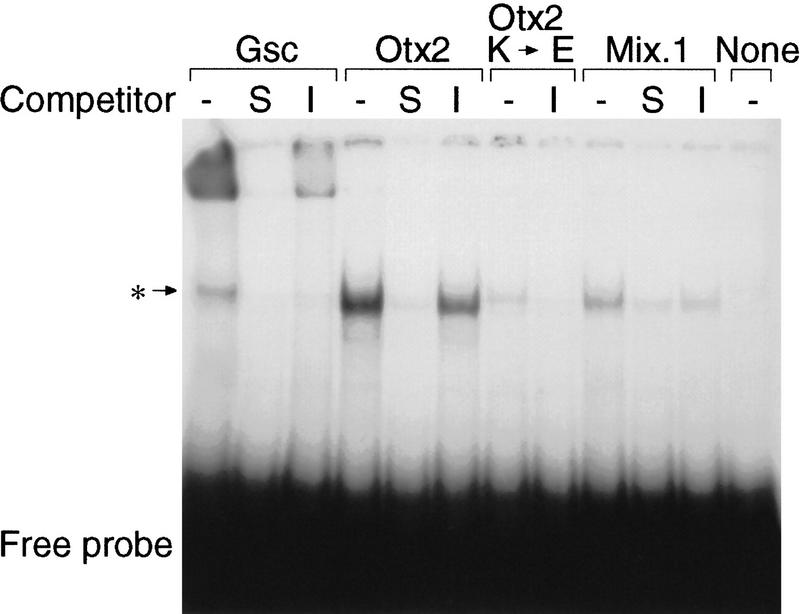

Goosecoid, Xotx2, and Mix.1 proteins were prepared by in vitro translation and tested for the ability to bind to the Bicoid and Antennapedia sites in the Xbra2 5′-flanking region (nucleotides −174 to −152). Both goosecoid and Xotx2 bind the −174/−152 probe specifically (Fig. 6). As expected, no specific binding was observed with Xotx2 K → E (Fig. 6). Mix.1 also forms a complex with the −174/−152 probe, but this is rather weak, perhaps reflecting a lower affinity for the site; Wilson et al. (1993) have also observed that Mix.1 binds only weakly to a single site.

Figure 6.

goosecoid, Xotx2, and Mix.1 bind to the −174/−152 region of the Xbra2 promoter. goosecoid, Xotx2, and Mix.1 were translated in a coupled transcription–translation system; the DNA template used in each reaction is indicated above the brackets. In some cases, binding reactions were preincubated with a 200-fold molar excess of specific competitor (unlabeled −174/−152 oligonucleotide, S) or with a 200-fold molar excess of irrelevant competitor (unlabeled −43/−19 oligonucleotide, I). Complexes were resolved on a 4% polyacrylamide gel. The asterisk (*) indicates the position of a nonspecific DNA-binding complex; this complex varied between lanes and between different experiments.

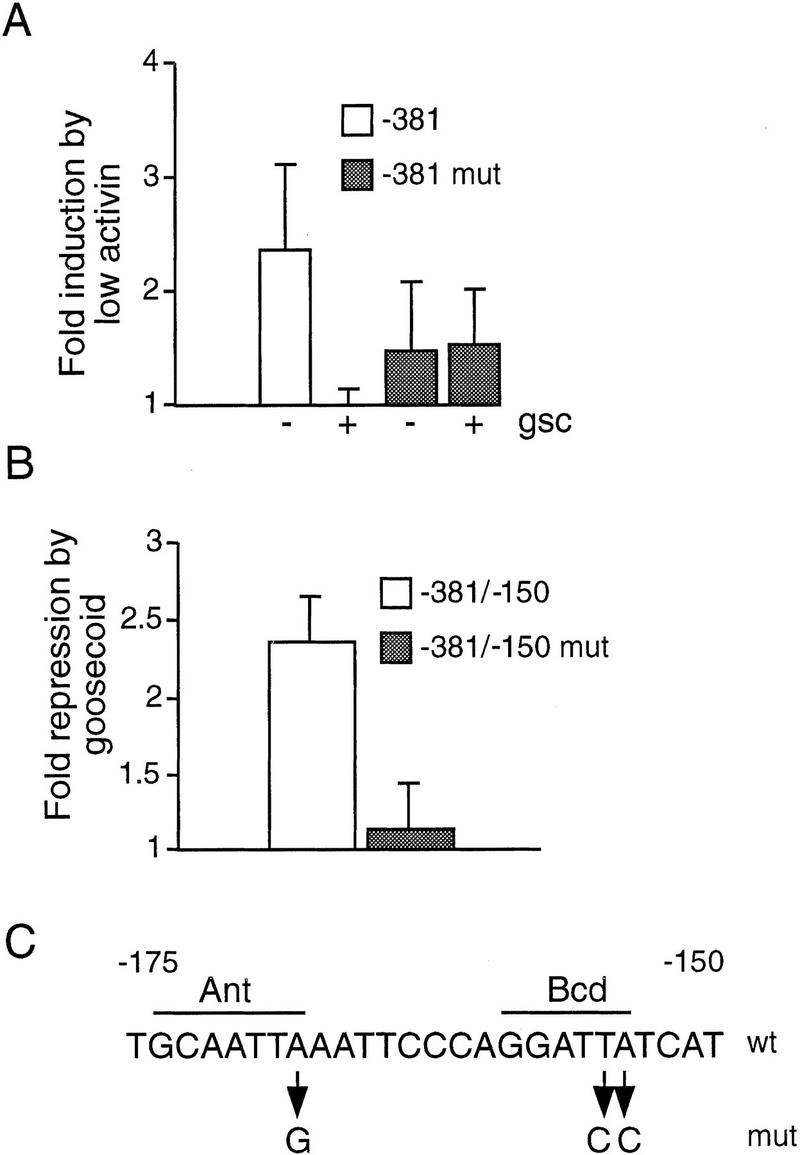

Goosecoid acts on the −381Xbra2 promoter through Antennapedia and Bicoid sites

To investigate whether the Antennapedia and Bicoid binding sites identified in the −174/−152 region are involved in suppression of Xbra2 expression, we have mutated them in the background of the −381Xbra2 construct, the shortest promoter fragment that is inducible by FGF and low concentrations of activin. This construct was chosen over larger ones because it has only two sites predicted to bind paired-type homeodomain proteins. To further simplify analysis, we have concentrated on goosecoid as a representative paired-type homeodomain protein, and to compare directly the activities of wild-type and mutant constructs, we have coinjected them into the same embryos, with the wild-type construct driving expression of Renilla luciferase and the mutant construct driving firefly luciferase.

Figure 7A shows that activin-induced reporter activity is suppressed by goosecoid in the wild-type reporter construct but not in the mutant construct in which the Antennapedia and Bicoid binding sites are destroyed (Fig. 7C). Induction of the mutant construct by low levels of activin in these experiments appears to be weaker than induction of the wild-type construct (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Suppression of −381Xbra2.luciferase activity by goosecoid requires Antennapedia and Bicoid homeodomain-binding sites. (A) Embryos were injected with 15 pg mutated −381Xbra2.firefly luciferase (see C), 15 pg −381Xbra2.Renilla luciferase, and 30 pg pEF-1α.β-galactosidase; in addition to this combination of DNAs, some embryos were injected with 1 pg of activin mRNA or with a mixture of 1 pg of activin mRNA and 1 ng of goosecoid mRNA. Animal caps were excised at the blastula stage and incubated until stage 12.5, when firefly and Renilla luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were determined. The graph shows fold induction by activin in the presence or absence of goosecoid, as obtained with the wild-type and mutated reporters. Normalized luciferase activities from four independent experiments were used in this figure. Bars show s.d.s. (B) NIH-3T3 cells were cotransfected in duplicate with a combination of CMV overexpression vector (either empty or goosecoid expressing), wild-type or mutated Xbra2/SV40 reporter, and reference plasmid. Luciferase activities were determined, and the results are expressed as the fold repression of reporter activity by goosecoid for each construct. Data from four experiments was used for this graph. Bars show s.d.s. (C) Sequence of the wild-type and the mutant Antennapedia and Bicoid sites.

To investigate whether goosecoid is also able to suppress Xbra2 promoter activity in a heterologous system, we have used transient transfections of NIH-3T3 mouse embryo fibroblasts. The activity of −381Xbra2.luciferase reporter is very low in these cells and could not be used reliably as a baseline for studies of suppression. We therefore tested the Antennapedia and Bicoid sites by cloning the −381/−150 region of Xbra2 upstream of the SV40 minimal promoter. Figure 7B shows that goosecoid suppresses activity of the wild-type −381/−150.SV40 reporter but not that of the mutant version. Additional experiments indicate that mutation of the Bicoid site alone is sufficient to abolish the effect of goosecoid, as expected from its binding site preference (not shown).

Discussion

In this paper we demonstrate that sequences within 381 bp of the Xbra2 transcription initiation site confer FGF- and activin-mediated gene activation in animal cap explants. The response of reporter constructs to activin, like the response of the endogenous gene, is concentration dependent, thus offering an opportunity to study a threshold phenomenon in a vertebrate embryo. Our results suggest that the down-regulation of Xbra2 expression in response to high concentrations of activin is attributable to suppression by homeodomain-containing proteins such as goosecoid, Xotx2, and Mix.1.

Expression of Xbra2 and sequence of the Xbra2 promoter

The existence of two Brachyury genes, Xbra and Xbra2, is consistent with the pseudotetraploid nature of the Xenopus laevis genome (Kobel and Du Pasquier 1986). The regulation of Xbra2 is similar to that of Xbra (Smith et al. 1991), suggesting that they play similar roles in mesodermal differentiation.

Inspection of the sequence of the Xbra2 promoter region reveals, in addition to potential binding sites for homeodomain-containing proteins, the presence of three sites similar to the half-palindrome binding site for Xbra protein (AGGTGT or the complementary ACACCT) at positions −473 to −468, −307 to −302, and −217 to −211 (Kispert and Herrmann 1993). Such sequences would normally be predicted to occur only once every 2048 bp; so the clustering of three within 262 bp may be of significance. Because Xbra can activate its own transcription (Rao 1994), it will be of interest to determine whether Xbra can bind to these sequences in vitro and whether mutations in them impair autoregulation. Recent experiments suggest, however, that Xbra activates its own transcription indirectly (Tada et al. 1997).

The Xbra2 promoter sequence bears no homology to the regulatory region of its mouse homolog, Brachyury (T), even though the mouse sequence is sufficient to direct expression in the primitive streak (Clements et al. 1996). It is possible that homologous sequences are located at nonconserved sites or that different mechanisms regulate the expression of these orthologs. Because regulatory elements are conserved frequently between orthologs (Nonchev et al. 1996), it will be of interest to understand this apparent difference in the mechanism of regulation between Xbra and T, as it may shed light on the evolution of regulatory pathways. There is also little similarity between the Xbra2 promoter sequence and that of Ciona intestinalis Brachyury (Corbo et al. 1997), although we note that a putative Suppressor of hairless site (TTCCCAGG), which may play a role in regulation of Ciona intestinalis Brachyury expression (Corbo et al. 1997), is present between nucleotides −165 and −158.

It is also noteworthy that the activin-responsive regions of the Xenopus genes goosecoid (Watabe et al. 1995), Mix.2 (Huang et al. 1995; Vize 1996), and XFD-1′ (Kaufmann et al. 1996) are dissimilar and that none shows significant homology to the Xbra2 promoter. These results suggest that there are multiple activin-responsive transcription factors, rather than a single dedicated factor that is shared by all activin-inducible immediate-early genes.

Xbra2 promoter sequences up to −2.1 kb respond to endogenous mesoderm-inducing signals

Xbra2 5′-flanking sequence (2.1 kb) drives mesoderm-specific expression of reporter constructs in Xenopus embryos. Lack of reporter gene expression in the dorsal marginal zone (Fig. 2E) indicates, as in the mouse embryo (Clements et al. 1996), that additional Xbra promoter elements are required for notochord expression.

Sequences within −381 bp of the Xbra2 transcription start site respond to both FGF and activin

Experiments using animal cap tissue revealed that 2.1 kb of Xbra2 5′-flanking sequence is sufficient to confer responsiveness to FGF, to components of the FGF signal transduction pathway, and to activin. Our attempts to map precisely FGF- and activin-response elements were thwarted, however, by variability from experiment to experiment. This variability is likely to be owing to several factors, including mosaic expression of the reporter construct (Vize et al. 1991), heterogeneity of different embryo batches, and perhaps the absence of some elements required for full activity of the Xbra2 promoter. It may also be that distinct elements are required for activation and for subsequent maintenance of Xbra2 expression (not shown; see also Clements et al. 1996). We are currently testing the effects of additional Xbra2 genomic sequences; preliminary results show that adding 2 kb of Xbra2 sequence downstream of +54 has no effect on the inducibility of the −2.1 kb promoter by activin. Nevertheless, our data (Fig. 3) allow us to conclude that elements that respond to FGF and activin reside between −381 bp and −231 bp of the Xbra2 transcription start site. The response of the −381-bp construct is weaker than that of the larger −1.0- or −2.1-kb reporter constructs (Fig. 3), suggesting that elements between −1000 and −381 are required for enhancement of the transcriptional response.

Dose-dependent effects of activin on activation of the Xbra2 promoter sequences

Although identification of activin- and FGF-responsive elements in the Xbra2 promoter has proved troublesome, we observe consistently that whereas low concentrations of activin elevate expression of a reporter gene driven by the Xbra2 promoter, high concentrations cause a strong down-regulation. In this respect, the Xbra2 reporter construct resembles the endogenous Xbra gene (Green et al. 1992, 1994; Gurdon et al. 1994, 1995; Jones et al. 1996), and the behavior of the reporter construct offers an opportunity to investigate the mechanism by which Xbra expression is activated only in a narrow window of activin concentrations. This phenomenon may be important in ensuring that Xbra and Xbra2 are expressed in the right regions of the embryo. For example, levels of activin, or an activin-related molecule such as Vg1 (Weeks and Melton 1987), might be too high in the vegetal hemisphere of the late blastula/early gastrula to allow expression of Xbra and too low in the animal hemisphere; only in the marginal zone might the concentration be appropriate (Gurdon et al. 1994, 1995; Jones et al. 1996).

Suppression of Xbra2 expression by goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2

High concentrations of activin cause the expression of Xbra2 reporter constructs to fall below baseline levels, implying active suppression of Xbra2 expression. This might occur through the induction, by high concentrations of activin, of gene products that suppress expression of Xbra2. As discussed in Results, two candidate Xbra2 repressors are goosecoid and Mix.1, both of which are induced by high levels of activin (Green et al. 1992, 1994; Gurdon et al. 1994, 1995, 1996). goosecoid and Mix.1 both encode paired class homeodomains (Rosa 1989; Blumberg et al. 1991), and another member of this family is Xotx2, which is also expressed in the marginal zone of the early Xenopus embryo and may be a target of goosecoid regulation (Blitz and Cho 1995; Pannese et al. 1995). Our experiments show that overexpression of all three homeobox-containing genes leads to suppression of Xbra2, both in whole embryos and in the animal cap mesoderm induction assay. This suppression can occur at the level of transcriptional regulation, because a similar effect is observed using Xbra2 reporter constructs. Suppression of Xbra expression by goosecoid has also been reported by Artinger et al. (1997).

In our attempts to understand the roles of homeobox-containing genes in the suppression of Xbra expression, we have focused on goosecoid and on a −174/−152 promoter fragment that contains Antennapedia and Bicoid binding sites to which goosecoid, Mix.1, and Xotx2 bind (Fig. 6; see also Artinger et al. 1997). Mutating these sites in a −381Xbra2 reporter construct abolishes suppression of activin-induced activity by goosecoid (Fig. 7A). Similarly, the integrity of these sites is necessary for repression by goosecoid of the activity of a heterologous promoter fusion carrying a −381/−150 fragment in NIH-3T3 cells (Fig. 7B). Together, these data argue that goosecoid, and perhaps Mix.1 and Xotx2 as well, down-regulate Xbra expression through direct transcriptional repression.

Might these genes repress Xbra expression during normal Xenopus development? The case is strong for goosecoid, which appears to be transiently coexpressed with Xbra both in intact embryos (Artinger et al. 1997; also cf. Gurdon et al. 1994; Vodicka and Gerhart 1995; Ryan et al. 1996) and in activin-treated animal caps (Gurdon et al. 1994, 1995, 1996). Furthermore, Goriely et al. (1996) suggest that goosecoid functions as a repressor, and our own results (Fig. 7B) and those of Artinger et al. (1997) are consistent with this. Of the other two genes, Xotx2 is expressed maternally and is strongly up-regulated at the onset of zygotic transcription; its gastrula-stage domain of expression is very similar to that of goosecoid, and goosecoid may regulate expression of Xotx2 (Blitz and Cho 1995). The mammalian ortholog of Xotx2 is able to transactivate from a bicoid target sequence, but in certain contexts some transcription activators are also able to function as repressors (Roberts and Green 1995). Finally, Mix.1 (Rosa 1989) and its pseudoallele Mix.2 (Vize 1996) are both expressed in the endoderm and mesoderm of the gastrula-stage embryo (see The Xenopus molecular marker resource; URL http://vize222.zo.utexas.edu/) and overlap with the expression domain of Xbra. The Mix genes may particularly be involved in ensuring that Xbra is not expressed in the vegetal hemisphere of the embryo. Like Otx2, Mix.1 has been suggested to function as a transcriptional activator (Mead et al. 1996), but, particularly in the presence of goosecoid, with which it can bind DNA cooperatively (Wilson et al. 1993), it may also act as a repressor.

Conclusion

Overall, our results are consistent with the simplest model imaginable to explain the response of Xbra to different concentrations of activin. At low doses, activin induces expression of Xbra. At higher concentrations, it also activates expression of genes such as goosecoid and Mix.1. These homeodomain-containing proteins then repress transcription of Xbra to give the observed off–on–off pattern that is observed as the concentration of activin is increased.

Materials and methods

Construction and screening of a size-selected phage λ genomic library

Attempts to isolate genomic clones containing the first exon of Xbra by screening conventional genomic libraries were unsuccessful. We therefore made a library from size-selected restriction fragments known to contain 5′ exons. These were identified by hybridizing a fragment containing the first 350 bp of Xbra cDNA to restriction digests of genomic DNA. BamHI fragments ranging from 4 kb to 6 kb were then isolated from an agarose gel and cloned into BamHI-digested Lambda ZapExpress vector (Stratagene). The resulting library was screened at high stringency using the first 350 bp of Xbra cDNA, and two identical clones, 3A1 and 3B1, were isolated.

Primer extension analysis

An oligonucleotide primer complementary to nucleotides +110 to +129 in Xbra2 was end-labeled using [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. After purification, the labeled primer was mixed with 50 μg total RNA in 0.4 m KCl and incubated at 70°C for 5 min followed by 50°C for 1 hr. Nucleic acids were precipitated with ethanol, resuspended in water, and reverse-transcribed with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Sciences). RNase A was added to 0.1 mg/ml, and after 10 min at room temperature cDNA was analyzed by denaturing PAGE.

Plasmid constructs

Luciferase-based vectors

A SpeI–BclI fragment containing 53 bp of exon 1 and 2.1 kb of 5′-flanking sequence was isolated from 3A1 and subcloned into the promoterless luciferase vector pGL2Basic (Promega) to generate Xbra2.pGL2. One-kilobase and 150-bp deletion constructs were made using PstI and SacI, respectively.

A finer deletion series of the Xbra2 flanking sequence was generated using the polymerase chain reaction, using the same 3′ primer (nucleotides +34 to +48) in all cases and various 5′ primers. A −381/+54 fragment was transferred into the Renilla luciferase vector pRLNull (Promega) to generate the plasmid used in Figure 7A. Antennapedia and Bicoid sites in −381.Xbra2 were mutated using the Chameleon kit (Stratagene) and oligonucleotide 5′-GACTTGCAATTGATTCCCAGGATCCTCCATAGAGCT-3′. Fragments (−381/−150) from the wild-type and mutant −381.Xbra2 plasmids were removed with SacI and cloned into pGL3Promoter (Promega).

Human β-globin-based vector

The luciferase gene of Xbra2.pGL2 was removed by digestion with HindIII and SalI and replaced with the β-globin gene isolated from p128.β/C (Mohun et al. 1989).

GFP-based vector

A HindIII–BamHI cDNA fragment encoding GFP (Zernicka-Goetz et al. 1996) was used to replace the luciferase gene in a pGL3 Promoter (Promega) construct carrying 2.1 kb of the Xbra2 promoter.

Vectors used for normalization

pSV.β-galactosidase contains the SV40 early promoter and enhancer driving lacZ (Promega). pEF-1α.β-galactosidase contains the EF-1α promoter derived from the plasmid pXEX (Johnson and Krieg 1994). This drives higher levels of lacZ than pSV.β-galactosidase. pRL–SV (Renilla luciferase under the control of the SV40 promoter and enhancer) and pRL–CMV were from Promega.

Xenopus embryo culture, microinjection, and transgenics

Xenopus laevis embryos were obtained according to Smith and Slack (1983) and staged according to Nieuwkoop and Faber (1967). Animal caps were dissected at stage 8, and they were cultured in 75% NAM (Slack 1984). Where FGF-2 (25 ng/ml) was included in the medium, bovine serum albumin was added to 0.1%. Embryos were injected with RNA as described (Smith 1993).

Xbra2 reporter constructs were injected in circular or linearized form; reference plasmids were injected in circular form. Embryos were microinjected at the one- or two-cell stage with 10–30 pg of Xbra2 reporter DNA together with 80 pg of pSV.β-galactosidase or 80 pg of pEF-1α-β-galactosidase, or 10 pg of pRL-SV.

Transgenic embryos were generated as described by Amaya and Kroll (1997) using MluI-digested Xbra2.GFP.

RNase protection assays

RNase protections were performed as described (Smith 1993). Xbra2–β-globin fusion transcripts from Xbra2.βg were detected using a probe made from plasmid Xbra2.βgcDNA; details are available on request. To detect transcripts of the endogenous Xbra2 gene, a 370-bp SacI fragment comprising nucleotides −148 to +222 of Xbra2 was subcloned into pBluescript to generate pSac370.9. This plasmid was linearized with BamHI and transcribed with T7 polymerase. Loading control probe EF-1α has been described previously (Cunliffe and Smith 1992).

In vitro transcription

In vitro transcription using SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase was as described by Smith (1993). v-Ras cDNA was the gift of Dr. M. Whitman (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Other clones include MEK1S217E/S221E (Umbhauer et al. 1995), Xenopus activin B (Thomsen et al. 1990), Xotx2 and Xotx2 K → E (Pannese et al. 1995), and goosecoid (Cho et al. 1991). Mix.1 cDNA (gift of F. Rosa, Ecole Norwale Supérieure, Paris, France) was cloned into pSP64TXB (a modified form of pSP64T prepared by Dr. M. Tada); the resulting plasmid was linearized with EcoRI and transcribed with SP6 polymerase. Amounts of RNAs used in injections were v-Ras, 100 pg; MEK1S217E/S221E, 1 ng; activin B, 1–100 pg (see legends to Figs. 3 and 4); goosecoid, Mix.1, Xotx2, and Xotx2 K → E, 0.5 ng per blastomere.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Whole-mount in situ hybridization to albino Xenopus embryos was according to Harland (1991) except that the substrate used for the chromogenic reaction was Boehringer Mannheim Purple AP Substrate. Xbra2 transcripts were detected using the plasmid pSac370.9ΔEM; details are available on request. A probe specific for Xbra was made by digesting pXT1 (Smith et al. 1991) with StuI and transcribing with T7 RNA polymerase. A probe specific for GFP was made by cloning a blunt-ended HindIII–BamHI GFP fragment (Zernicka-Goetz et al. 1996) into StuI-digested pCS2+ (Rupp et al. 1994).

Luciferase and β-galactosidase assays

When firefly luciferase assays were performed using β-galactosidase for normalization, embryos (∼5) or animal caps (∼20) were frozen on dry ice and then lysed in 5–10 volumes of lysis buffer (Promega). The lysate was clarified by brief centrifugation; 40% was assayed for luciferase activity using the Promega Luciferase Assay System, and the remaining 60% was assayed for β-galactosidase activity (Sambrook et al. 1989).

In experiments where Renilla luciferase was used for normalization, dual-luciferase assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Promega). Twelve to 20 animal caps per sample were lysed in 30–50 μl of lysis buffer; 0.2 to 0.5-animal cap equivalents were used in measurements of luciferase activity.

Electrophoretic mobility-shift assay

Proteins for use in binding reactions were translated in the TNT coupled transcription–translation system (Promega). All four proteins translated with similar efficiency, as assessed by incorporation of [35S]methionine and analysis by SDS-PAGE. One microliter of translation reaction was used in each binding reaction, which included 12 mm HEPES at pH 7.6, 60 mm KCl, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 3 mm spermidine, 0.5 mm PMSF, 12% glycerol, 3 μg of pBluescript KS as a nonspecific DNA competitor, and ∼0.4 ng (5 × 104–7 × 104 cpm) of 32P-labeled probe. Probe was made by annealing oligonucleotides 5′-TCGAGCAATTAAATTCCCAGGATTATC and 5′-TCGAGATAATCCTGGGAATTTAATTGC and labeling them with Klenow enzyme in the presence of [32P]dCTP, dATP, dTTP, and dGTP (Sambrook et al. 1989). Nucleotides shown in italics are not derived from Xbra2 sequences. Binding reactions were preincubated for 20–25 min at room temperature, after which probe was added. After a further 10 min at room temperature, samples were analyzed on a 4% polyacrylamide gel.

Cell culture and transfections

NIH-3T3 mouse fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Sigma) supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml of streptomycin. Calcium-phosphate transfections were performed as described (Sambrook et al. 1989) in six-well plates. A total of 5 μg of DNA per well was used: 4 μg of pCDNA3 or pCDNA3–goosecoid, 0.5 μg of Xbra2 reporter plasmid, and 0.5 μg of reference plasmid (either pRL–CMV or pRL–SV40). Cells were analyzed for luciferase activities 3 days after transfection as described above. Each sample was transfected in duplicate. goosecoid cDNA (Blumberg et al. 1991) was cloned into the pcDNA3 vector (containing the CMV promoter/enhancer; Invitrogen) using EcoRI and XhoI.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Medical Research Council. We thank members of our laboratory for discussions, Masa Tada for help with in situs, Tim Mohun for advice, and members of the NIMR Molecular Immunology Division for use of their luminometer. We are also very grateful to Ken Cho (University of California, Irvine, CA) for a helpful discussion which directed us to analysis of goosecoid, to Enrique Amaya (Wellcome/CRC, Cambridge, UK) for advice on making transgenic Xenopus, and to Richard Treisman (Imperial Cancer Research Foundation, London, UK) for advice on transcription. B.V.L. was supported by the ESF Developmental Biology Programme and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), V.C. was supported by EC BioTech grant PL920102, M.U. was supported by a CEC Human Capital Mobility grant, W.L. is supported by Boehringer-Ingelheim Fonds, and J.C.S. is an International Scholar of the HHMI.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL j-im@nimr.mrc.ac.uk; FAX 0181 913 8584.

References

- Amaya E, Kroll KL. A method for generating transgenic frog embryos. In: Sharpe P, Mason I, editors. Methods in cell biology. Molecular embryology: Methods and protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc.; 1997. . (In press). [Google Scholar]

- Artinger M, Blitz I, Inoue K, Tran U, Cho KWY. Interaction of goosecoid and brachyury in Xenopus mesoderm patterning. Mech Dev. 1997;65:187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asashima M, Nakano H, Shimada K, Kinoshita K, Ishii K, Shibai H, Ueno N. Mesodermal induction in early amphibian embryos by activin A (erythroid differentiation factor) Roux’s Arch Dev Biol. 1990;198:330–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00383771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz IL, Cho KWY. Anterior neurectoderm is progressively induced during gastrulation: The role of the Xenopus homeobox gene orthodenticle. Development. 1995;121:993–1004. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg B, Wright CVE, De Robertis EM, Cho KWY. Organizer-specific homeobox genes in Xenopus laevis embryos. Science. 1991;253:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.1677215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KWY, Blumberg B, Steinbeisser H, De Robertis EM. Molecular nature of Spemann’s organizer: The role of the Xenopus homeobox gene goosecoid. Cell. 1991;67:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90288-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements D, Taylor HC, Herrmann BG, Stott D. Distinct regulatory control of the Brachyury gene in axial and non-axial mesoderm suggests separation of mesodermal lineages early in mouse gastrulation. Mech Dev. 1996;56:139–149. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon FL, Sedgwick SG, Weston KM, Smith JC. Inhibition of Xbra transcription activation causes defects in mesodermal patterning and reveals autoregulation of Xbra in dorsal mesoderm. Development. 1996;122:2427–2435. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbo JC, Levine M, Zeller RW. Characterization of a notochord-specific enhancer from the Brachyury promoter region of the ascidian, Ciona intestinalis. Development. 1997;124:589–602. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.3.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunliffe V, Smith JC. Ectopic mesoderm formation in Xenopus embryos caused by widespread expression of a Brachyury homologue. Nature. 1992;358:427–430. doi: 10.1038/358427a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Specification of mesodermal pattern in Xenopus laevis by interactions between Brachyury, noggin, and Xwnt-8. EMBO J. 1994;13:349–359. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale L, Slack JM. Fate map for the 32-cell stage of Xenopus laevis. Development. 1987;99:527–551. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplan C, Theis J, O’Farrell PH. The sequence specificity of homeodomain-DNA interaction. Cell. 1988;54:1081–1090. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90123-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson S, Gurdon JB. Activin signalling has a necessary function in Xenopus early development. Curr Biol. 1996;7:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goriely A, Stella M, Coffinier C, Kessler D, Mailhos C, Dessain S, Desplan C. A functional homologue of goosecoid in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:1641–1650. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JBA, New HV, Smith JC. Responses of embryonic Xenopus cells to activin and FGF are separated by multiple dose thresholds and correspond to distinct axes of the mesoderm. Cell. 1992;71:731–739. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90550-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JBA, Smith JC, Gerhart JC. Slow emergence of a multithreshold response to activin requires cell-contact-dependent sharpening but not prepattern. Development. 1994;120:2271–2278. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JBA, Cooke TL, Smith JC, Grainger RM. Anteroposterior neuraxis specification induced by activin-induced mesoderm. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:8596–8601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB, Harger P, Mitchell A, Lemaire P. Activin signalling and response to a morphogen gradient. Nature. 1994;371:487–492. doi: 10.1038/371487a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB, Mitchell A, Mahony D. Direct and continuous assessment by cells of their position in a morphogen gradient. Nature. 1995;376:520–521. doi: 10.1038/376520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB, Mitchell A, Ryan K. An experimental system for analyzing response to a morphogen gradient. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:9334–9338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern ME, Ho RK, Walker C, Kimmel CB. Induction of muscle pioneers and floor plate is distinguished by the zebrafish no tail mutation. Cell. 1993;75:99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanes SD, Brent R. A genetic model for interaction of the homeodomain recognition helix with DNA. Science. 1991;251:426–430. doi: 10.1126/science.1671176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland RM. In situ hybridization: An improved whole mount method for Xenopus embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:675–685. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann BG, Labeit S, Poutska A, King TR, Lehrach H. Cloning of the T gene required in mesoderm formation in the mouse. Nature. 1990;343:617–622. doi: 10.1038/343617a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H-C, Murtaugh LC, Vize PD, Whitman M. Identification of a potential regulator of early transcriptional responses to mesoderm inducers in the frog embryo. EMBO J. 1995;14:5965–5973. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AD, Krieg PA. pXeX, a vector for efficient expression of cloned sequences in Xenopus embryos. Gene. 1994;147:223–226. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Armes N, Smith JC. Signalling by TGF-β family members: Short-range effects of Xnr-2 and BMP-4 contrast with the long-range effects of activin. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1468–1475. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00751-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann E, Paul H, Friedle H, Metz A, Scheucher M, Clement JH, Knöchel W. Antagonistic actions of activin A and BMP-2/4 control dorsal lip-specific activation of the early response gene XFD-1′ in Xenopus laevis embryos. EMBO J. 1996;15:6739–6749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kispert A, Herrmann BG. The Brachyury gene encodes a novel DNA binding protein. EMBO J. 1993;12:3211–3220. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kispert A, Korschorz B, Herrmann BG. The T protein encoded by Brachyury is a tissue-specific transcription factor. EMBO J. 1995a;14:4763–4772. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kispert A, Ortner H, Cooke J, Herrmann BG. The chick Brachyury gene: Developmental expression pattern and response to axial induction by localized activin. Dev Biol. 1995b;168:406–415. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobel HR, Du Pasquier L. Genetics of polyploid Xenopus. Trends Genet. 1986;3:310–315. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig KD, Kroll KL, Sun EE, Kirschner MW. Expression cloning of a Xenopus T-related gene (Xombi) involved in mesodermal patterning and blastopore lip formation. Development. 1996;122:4001–4012. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead PE, Brivanlou IH, Kelley CM, Zon LI. BMP-4-responsive regulation of dorsal-ventral patterning by the homeobox protein Mix.1. Nature. 1996;382:357–360. doi: 10.1038/382357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohun TJ, Taylor MV, Garrett N, Gurdon JB. The CArG promoter sequence is necessary for muscle-specific transcription of the cardiac actin gene in Xenopus embryos. EMBO J. 1989;8:1153–1161. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: North Holland; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Nonchev S, Maconochie M, Vesque C, Aparicio S, Ariza-McNaughton L, Manzanares M, Maruthainar K, Kuroiwa A, Brenner S, Charnay P, Krumlauf R. The conserved role of Krox-20 in directing Hox gene expression during vertebrate hindbrain segmentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:9339–9345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly M-AJ, Smith JC, Cunliffe V. Patterning of the mesoderm in Xenopus: Dose-dependent and synergistic effects of Brachyury and Pintallavis. Development. 1995;121:1351–1359. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannese M, Polo C, Andreazzoli M, Vignali R, Kablar B, Barsacchi G, Boncinelli E. The Xenopus homologue of Otx2 is a maternal homeobox gene that demarcates and specifies anterior body regions. Development. 1995;121:707–720. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao Y. Conversion of a mesodermalizing molecule, the Xenopus Brachyury gene, into a neuralizing factor. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:939–947. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly KM, Melton DA. Short-range signaling by candidate morphogens of the TGF beta family and evidence for a relay mechanism of induction. Cell. 1996;86:743–754. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SG, Green MR. Dichotomous regulators. Nature. 1995;375:105–106. doi: 10.1038/375105a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa FM. Mix.1, a homeobox mRNA inducible by mesoderm inducers, is expressed mostly in the presumptive endodermal cells of Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1989;57:965–974. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz i Altaba A, Jessell TM. Pintallavis, a gene expressed in the organizer and midline cells of frog embryos: Involvement in the development of the neural axis. Development. 1992;116:81–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.Supplement.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp RAW, Snider L, Weintraub H. Xenopus embryos regulate the nuclear localization of XMyoD. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:1311–1323. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.11.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K, Garrett N, Mitchell A, Gurdon JB. Eomesodermin, a key early gene in Xenopus mesoderm differentiation. Cell. 1996;87:989–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81794-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Merker S, Ho RK, Herrmann BG, Nüsslein-Volhard C. The protein product of the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T gene is expressed in nuclei of the germ ring and the notochord of the early embryo. Development. 1992;116:1021–1032. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Merker S, van Eeden FM, Halpern ME, Kimmel CB, Nüsslein-Volhard C. No tail (ntl) is the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T (Brachyury) gene. Development. 1994;120:1009–1015. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sive HL. The frog prince-ss: A molecular formula for dorsoventral patterning in Xenopus. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:1–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack JMW. Regional biosynthetic markers in the early amphibian embryo. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984;80:289–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Inducing factors in Xenopus early embryos. Curr Biol. 1994;4:116–126. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(94)00027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC. Purifying and assaying mesoderm-inducing factors from vertebrate embryos. In: Hartley D, editor. Cellular interactions in development—A practical approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Slack JMW. Dorsalization and neural induction: Properties of the organizer in Xenopus laevis. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1983;78:299–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Price BMJ, Van NK, Huylebroeck D. Identification of a potent Xenopus mesoderm-inducing factor as a homologue of activin A. Nature. 1990;345:732–734. doi: 10.1038/345729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Price BMJ, Green JBA, Weigel D, Herrmann BG. Expression of a Xenopus homolog of Brachyury (T) is an immediate-early response to mesoderm induction. Cell. 1991;67:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90573-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ST, Jaynes JB. A conserved region of engrailed, shared among all en-, gsc-, Nk1-, Nk2- and msh-class homeoproteins, mediates active transcriptional repression in vivo. Development. 1996;122:3141–3150. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stennard F, Carnac G, Gurdon JB. The Xenopus T-box gene, Antipodean, encodes a vegetally localised maternal mRNA and can trigger mesoderm formation. Development. 1996;122:4179–4188. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada M, O’Reilly M-AJ, Smith JC. Analysis of competence and of Brachyury autoinduction by use of hormone-inducible Xbra. Development. 1997;124:2225–2234. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.11.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen G, Woolf T, Whitman M, Sokol S, Vaughan J, Vale W, Melton DA. Activins are expressed early in Xenopus embryogenesis and can induce axial mesoderm and anterior structures. Cell. 1990;63:485–493. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90445-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman J, Harris E, Wilson D, Desplan C. The homeodomain: A new face for the helix-turn-helix? BioEssays. 1992;14:145–150. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbhauer M, Marshall CJ, Mason CS, Old RW, Smith JC. Mesoderm induction in Xenopus caused by activation of MAP kinase. Nature. 1995;376:58–62. doi: 10.1038/376058a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vize PD. DNA sequences mediating the transcriptional response of the Mix.2 homeobox gene to mesoderm induction. Dev Biol. 1996;177:226–231. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vize PD, Melton DA, Hemmati-Brivanlou A, Harland RM. Assays for gene function in developing Xenopus embryos. Methods Cell Biol. 1991;36:367–387. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodicka MA, Gerhart JC. Blastomere derivation and domains of gene expression in the Spemann Organizer of Xenopus laevis. Development. 1995;121:3505–3518. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe T, Kim S, Candia A, Rothbacher U, Hashimoto C, Inoue K, Cho KWY. Molecular mechanisms of Spemann’s organizer formation: Conserved growth factor synergy between Xenopus and mouse. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:3038–3050. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.24.3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks DL, Melton DA. A maternal mRNA localized to the vegetal hemisphere in Xenopus eggs codes for a growth factor related to TGF-beta. Cell. 1987;51:861–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D, Sheng G, Lecuit T, Dostatni N, Desplan C. Cooperative dimerization of Paired class homeo domains on DNA. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:2120–2134. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernicka-Goetz M, Pines J, Ryan K, Siemering KR, Haseloff J, Evans MJ, Gurdon JB. An indelible lineage marker for Xenopus using a mutated green fluorescent protein. Development. 1996;122:3719–3724. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, King ML. Xenopus VegT RNA is localized to the vegetal cortex during oogenesis and encodes a novel T-box transcription factor involved in mesodermal patterning. Development. 1996;122:4119–4129. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]