Abstract

The CGG repeats are present in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of the fragile X mental retardation gene FMR1 and are associated with two diseases: fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) and fragile X syndrome (FXS). FXTAS occurs when the number of repeats is 55–200 and FXS develops when the number exceeds 200. FXTAS is an RNA-mediated disease in which the expanded CGG tracts form stable structures and sequester important RNA binding proteins. We obtained and analysed three crystal structures of double-helical CGG repeats involving unmodified and 8-Br modified guanosine residues. Despite the presence of the non-canonical base pairs, the helices retain an A-form. In the G–G pairs one guanosine is always in the syn conformation, the other is anti. There are two hydrogen bonds between the Watson–Crick edge of G(anti) and the Hoogsteen edge of G(syn): O6·N1H and N7·N2H. The G(syn)-G(anti) pair shows affinity for binding ions in the major groove. G(syn) causes local unwinding of the helix, compensated elsewhere along the duplex. CGG helical structures appear relatively stable compared with CAG and CUG tracts. This could be an important factor in the RNA’s ligand binding affinity and specificity.

INTRODUCTION

Tandem repeats of the CGG trinucleotide motif are abundant in human genome and occur in numerous genes and transcripts (1). The repeat tracts are often polymorphic in length in human population and may play a regulatory role in gene expression. The CGG repeats present in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of the fragile X mental retardation gene FMR1 are associated with several distinct phenotypes (2). In normal population the number of CGG repeats varies in the range 5–54 (2,3); 45–54 repeats fall into a subclass named ‘the grey zone’ associated with an increased likelihood of intergenerational pathogenic expansions (2,4). Tracts of 55–200 CGGs are premutations that can cause progressive neurodegenerative disorder fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) in elderly males (5,6). Female premutation carriers are at risk of developing premature ovarian failure (7). More than 200 CGG repeats are full mutations resulting in fragile X syndrome (FXS), the most common inherited mental retardation syndrome in man (8).

FXTAS is an RNA-mediated disease in which the level of FMR1 mRNA is significantly elevated (9,10). The expanded tracts form stable structures and sequester important RNA binding proteins which are normally required for splicing and other cellular processes (11,12). The protein sequestration results in the formation of intranuclear inclusions in neurons and astrocytes (12,13) and triggers a dynamic formation of aggregates and deregulation of alternative splicing of a number of genes in model cellular systems (11). In addition, the presence of stable CGG structures inhibits FMR1 translation at the initiation step, resulting in a deficiency of the encoded FMRP protein (9,14,15). FMRP is an important RNA binding protein involved in mRNA trafficking between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm and in regulating translation at the synapse (16).

The structure of the CGG repeats in FMR1 transcripts is a hairpin whose stem is formed by alternating C–G, G–C and the non-canonical G–G base pairs (17). Isolated (CGG)20 repeats are thermodynamically the most stable hairpins of all the (CNG)20 (N stands for C or G or A or U) repeats (18,19) which means that G–G pairs are the strongest of all homobasic interactions. According to an NMR study (20), the opposing G–G bases are highly dynamic in CGG repeat hairpin, having one G residue in anti and the other in syn conformation. Short CGG repeats were shown to form a duplex structure (20,21) and in the presence of potassium ions—G-tetraplexes (22–24). Thus, an RNA structure formed by CGG repeats is less clearly defined than in the case of CUG repeats (18,19,25) and CAG repeats (19,26–28) for which crystal structures have been determined (29–31).

In this study, we report three crystal structures of double-helical CGG repeats containing native and 8-Br modified guanosine residues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis, purification and crystallization of oligoribonucleotides

GCGGCGGC, GC(8-BrG)GCGGC and GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC oligomers were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems DNA/RNA synthesizer, using cyanoethyl phosphoramidite chemistry. Commercially available C and G phosphoramidites with 2′-O-tetrbutyldimethylsilyl were used for the synthesis of RNA (Glen Research, Azco, Proligo). The phosphoramidite 8-Br guanosine was synthesized according to Proctor et al. (32). The details of deprotection and purification of oligoribonucleotides were described previously (33).

All crystals were grown by the hanging drop/vapour diffusion method at 19°C. A single crystal of GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC grew in 10 months. The reservoir initially contained 10 mM MgCl2 50 mM Na cacodylate, pH 6.0 and 1.0 M Li2SO4. The crystallization drop initially contained 3 μl of RNA at 10 mg/ml and 1 mM MgCl2, and 3 μl of the reservoir solution. Crystals of GCGGCGGC grew in several days from the same solution as above, but involved crystal seeding and the starting RNA concentration of 2.4 mg/ml. The crystals grew as clusters of small needles which were then used for seeding. The seeded crystals grew from a similar solution but with the RNA concentration of 1.2 mg/ml. They appeared as single blocks but were in fact clusters of crystals that had to be separated. Crystals of GC(8-BrG)GCGGC grew in 2 months. The reservoir initially contained 10 mM CaCl2, 0.2 M NH4Cl, 50 mM Tris–HCl at pH 8.5 and 30% w/v PEG 4000. The crystallization drop initially contained 2 μl of RNA at 10 mg/ml and 1 mM MgCl2, and 2 μl of the reservoir solution.

X-ray data collection, structure solution and refinement

X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K: from GCGGCGGC on BL 14.2 beam line at the BESSY synchrotron (Berlin) to the resolution of 2.05 Å; from GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC and GC(8-BrG)GCGGC on EMBL X11, DESY, Hamburg, to the resolution of 1.45 Å and 0.97 Å, respectively. The crystals were cryoprotected by 20% glycerol (v/v) in the mother liquor. The data were integrated and scaled using the program suite DENZO/SCALEPACK (34).

The structure of GC(8-BrG)GCGGC was solved first. SHELXD was used to identify the positions of the Br atoms by analysing the Patterson function based on the anomalous signal (35). The program identified two sites at least five times higher than any other peaks. SHELXE was used to identify the correct enantiomorph and to calculate initial phases (35), the calculated electron density map was uninterpretable in terms of an atomic model, but showed parallel columns of density indicating stacked RNA duplexes. DM was used for density modification but the resulting maps were still uninterpretable (36). The phases from DM were used in a free-atom phase refinement with ‘shaking’ of the model, using ARP/wARP (37). In a total of 100 cycles of adding/removing atoms with nine round of shaking interspersed, the R-factor/R-free statistics initially remained apparently random but after 25 cycles started dropping and in the final 50 cycles collapsed to 0.188/0.256. The free-atom electron density map showed the RNA atoms clearly resolved and a well-defined solvent structure; the map looked very similar to the final map for the refined model. Both GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC and GCGGCGGC structures were solved by molecular replacement using PHASER (38). The initial models were poor but sufficient for the purpose of refinement and model extension. The manual rebuilding and map inspection were done using Coot (39).

All three structures were refined using Refmac5 (40) and Phenix (41). The final model of [GC(8-BrG)GCGGC]2 was refined without restraints and with anisotropic temperature factors. The last few cycles of the [GC(8-BrG)GCGGC]2 refinement were performed using all data, including the Rfree set. The other two models, GCGGCGGC and GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC, were refined using isotropic B-factors.

Helical parameters were calculated using 3DNA (42). Sequence-independent measures were used based on vectors connecting the C1′ atoms of the paired residues, to avoid computational artefacts arising from non-canonical base pairing. Program PBEQ-Solver (43) was used to calculate electrostatic potential map. All pictures were drawn using PyMOL v0.99rc6 (44). The coordinates of the crystallographic models have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession codes 3R1C, 3R1D and 3R1E.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The overall structures

The RNA in all three crystal structures has the form of duplexes stacking end-to-end and forming bundles of parallel columns. The crystals of the native RNA contain 18 (GCGGCGGC)2 duplexes in the P1 unit cell. Each column consists of all the 18 independent duplexes stacked consecutively (Supplementary Figure 1). In the atomic resolution C2 structure, there is one [GC(8-BrG)GCGGC]2 duplex in the asymmetric unit. The other monoclinic crystal contains five crystallographically independent RNA strands. They form three (GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC]2 duplexes, the third consisting of two symmetry-related strands. The native RNA and [GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC]2 structures contain sulphate ions from the crystallization medium, while [GC(8-BrG)GCGGC]2 crystals have Ca2+. All the ions interact in the major groove with the G–G pairs (details below). The final models are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the X-ray data and model refinement for (GCGGCGGC)2, [GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC]2 and [GC(8-BrG)GCGGC]2

| Crystal | GCGGCGGC | GC(8-BrG)GCGGC | GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beam line | BESSY BL 14.2 | EMBL-X11 | EMBL-X11 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9200 | 0.8126 | 0.8126 |

| Space group | P1 | C2 | C2 |

| Cell parameters | a = 39.7, b = 76.9, c = 85.4 Å, α = 90.0, β = 88.6, γ = 77.3° | a =50.7, b = 22.5, c = 44.2 Å, β = 117.8° | a = 118.6, b = 28.6, c = 61.8 Å, β = 118.0° |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20.0–2.05 (2.09–2.05)a | 20.0–0.97 (0.99–0.97) | 20.0–1.45 (1.47–1.45) |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.3 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 5–10 | 40 | 50 |

| Rmergeb | 0.093 (0.488) | 0.132 (0.934) | 0.112 (0.620) |

| <I/σ(I)> | 17 (2.8) | 9 (2.5) | 10 (3.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.4 (97.5) | 95.7 (93.4) | 99.8 (100.0) |

| No. unique reflections | 60 328 | 24 974 | 32 941 |

| Overall multiplicity | 4.4 (3.5) | 5.4 (4.7) | 7.5 (6.3) |

| Reflections > 3σ (%) | 71 (40) | 77 (29) | 77 (50) |

| B-factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 33 | 7.8 | 21.2 |

| Rwork | 21.56 | 13.66 | 23.21 |

| Rfreec | 25.71 | – | 27.02 |

| No. RNA atoms | 6304 | 370 | 1617 |

| Ions | 7 SO42− | 2 Ca2+ | 8 SO42− |

| No. water molecules | 524 | 103 | 207 |

| Other solvent | – | 1 glycerol | – |

| r.m.s. deviation from ideal values | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.145 | 1.746 | 1.282 |

| PDB code | 3R1C | 3R1E | 3R1D |

aValues in brackets are for the highest resolution shell.

bRmerge = Σhkl Σi |Ii(hkl) − <I(hkl)>|/Σhkl Σi Ii(hkl), where Ii(hkl) and <I(hkl)> are the observed individual and mean intensities of a reflection with indices hkl, respectively, Σi is the sum over the individual measurements of a reflection with indices hkl and Σhkl is the sum over all reflections.

cRfree was calculated using 5% of the total reflections chosen randomly and omitted from the refinement.

Non-canonical G–G pairing and its consequences on the duplex

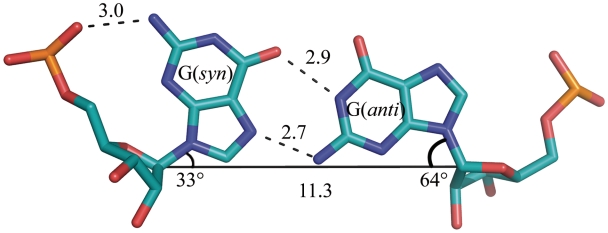

Despite the presence of the non-canonical base pairs, the helices have a typical A-form, with values of helical twist in the range 30–32 for all the duplexes, the sugar pucker C3′-endo or, in some cases, C2′-exo and Zp values of 2.63 ± 0.22 Å (for the A-form it should be more than 1.5 Å). The helices contain C–G and G–C base pairs with typical Watson–Crick interactions. Between them are the non-canonical G–G pairs in which one guanosine is always in the syn conformation while the other is anti (Figure 1), experimentally shown to be the preferred arrangement in double helical context (45–47). The syn-anti geometry of this base pair can be described as G/G cis Watson–Crick/Hoogsteen according to the nomenclature proposed by Leontis and Westhof (48). There are two hydrogen bonds between the guanosine residues: carbonyl oxygen is bonded to N1H, and N7 to the exo-amino group. All the H-bond distances are in the range 2.6–3.3 Å. The conformation of the G(syn) residue is additionally stabilized by a hydrogen bond between the exo-amino function and its phosphate oxygen atom (3.0 Å).

Figure 1.

Non-canonical G(syn)–G(anti) pair. Hydrogen bonds are drawn with dashed lines. Solid line connecting C1′ atoms gives a measure of strand separation. Angles λ are marked (see text).

The syn-anti arrangement avoids the steric clash between the two bulky guanines within the helical structure. This is evident from the C1′–C1′ distances between the paired residues: 11.3 ± 0.1 Å for G–G, compared with 10.7 ± 0.2 Å for the canonical C–G pairs. The angle λ of the glycosidic bond with the line connecting the C1′ atoms of each pair is 33 ± 4° for the G(syn) residues and 64 ± 3° for G(anti), compared with 54 ± 3° for the other residues. This means that the G(syn) is shifted towards the minor groove and the G(anti) towards to major groove, which optimizes the H-bonding interactions between the Hoogsteen and Watson–Crick edges, while avoiding the clash between the carbonyl oxygen atoms (Figure 1).

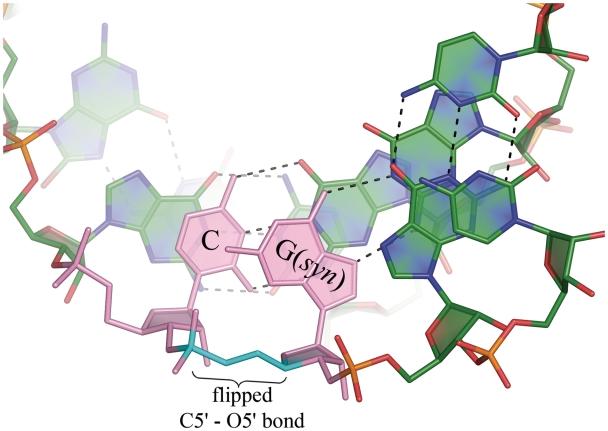

The G(syn) residues also show unusual α and γ backbone torsion angles. The α angle, representing a rotation about the P-O5′ bond, is +ac, +ap, or −ap (in one case) instead of the typical −sc. The angles range 107–182° with the average value of 142°, almost half a turn from the mean −sc value of −60°. The γ angle, about the C5′-C4′ bond, is +ap or −ap in the G(syn) residues, ranging 152° to −152°. This is ∼120° from the usual +sc. This amounts to flipping of the O5′-C5′ bond and a local ‘straightening’ of the sugar-phosphate backbone (Figure 2). The unusual torsion of the backbone is similar to the ‘extended’ conformation observed by Haran et al. (49) in a CG step of a DNA helix. In the present study this conformation seems to be necessary for the simultaneous (i) Hoogsteen–Watson–Crick pairing of the guanosines; (ii) the H-bond between exo-amino group of G(syn) with the phosphate O; and (iii) stacking against the neighbouring cytosine. These effects explain the accommodation of the G–G pair within the helix.

Figure 2.

The G(syn) residue in a helical context is nearly co-planar with the adjacent cytosine (pink). The torsion angles α, γ (cyan) are flipped with respect to typical values for A-form and the helix is locally unwound.

The local straightening of the sugar-phosphate backbone, amounting to a local unwinding of the helix, is compensated elsewhere along the duplex, and the overall statistics do not deviate from typical (Supplementary Tables 1–4). This is different from the case of CAG repeats (31) where a similar inversion of the α and γ angles is associated with the overall unwinding of the helix and broadening of the major groove to >20 Å (measured as the distance between lines connecting P atoms). For the native CGG-containing duplexes, the average width of the major groove was 17.9 ± 0.9 Å, for the longer Br-modified duplex it was 17.8 ± 2.5 Å and for the shorter modified structure 14.3 Å. The values for the minor groove were 15.8 ± 0.5 Å, 15.4 ± 0.5 Å and 16.1 Å, respectively. The values are not out of the ordinary for the A form.

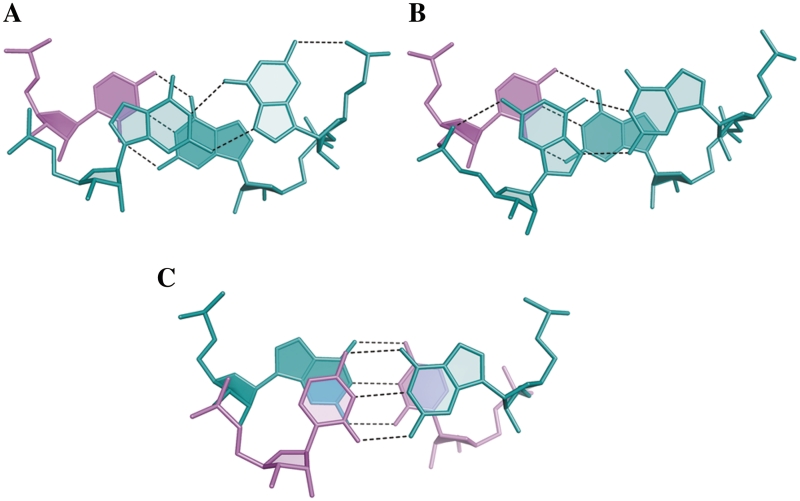

Another effect of the G(syn) conformation is that the guanine has no stacking interaction with the downstream G–C pair and it stacks against the preceding pair of residues (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Stacking interactions in the CGG duplex structure. (A and B)The non-canonical G–G pairs (aquamarine); (C) the canonical CG/GC step.

The effect of bromination and the distribution of G–G conformers

All the 8-Br modified guanosine residues are in the syn conformation, therefore the pairs are 8-BrG(syn)-G(anti). As observed before, duplexes containing the modified residues are more stable than the corresponding native duplexes. The melting temperature of [GC(8-BrG)GCGGC]2 is 13°C higher than for (GCGGCGGC)2 (21). In structural terms this is probably due to a restricting effect of Br on the conformational freedom and excluding the unfavourable G(anti)-G(anti) interactions. The crystallographic structures bear this out in the sense that the modified duplexes contain only well ordered 8-BrG(syn)-G(anti) pairs, while in the native duplexes each G–G pair is observed in one of three possible arrangements: G(syn)-G(anti), G(anti)-G(syn) or a statically disordered mixture of the two (in 2 out of 36 pairs). The three base-pairing arrangements occur with different frequencies and in various combinations of pairs along the native duplex. Symmetric arrangements are clearly favoured: anti-syn followed by syn-anti or vice versa (in 14 out of 18 cases). There is a slight preference, which can be fortuitous, for the former arrangement (8 cases as opposed to 6). Of the remaining four duplexes, two are clearly asymmetric and two contains statically disordered G–G pairs (Supplementary Table 5). In the longer modified duplexes, containing unmodified G–G pair in the middle, two of the native G–G pairs are disordered, showing both possible conformations; the third is ordered.

Apart from restricting the conformational freedom, and thus defining the conformation of the G–G pair, there is little crystallographic evidence that bromination alters the structure compared with the native RNA. The native and brominated duplexes can be superposed with an r.m.s. deviation of ∼1 Å. The similarity is also reflected in helical parameters. In terms of interactions with the solvent, the Br atom seems to displace a water molecule, which in native G(syn) is located ∼3.2 Å from C8, in the minor groove, but its main effect appears to be steric. In terms of H-bonding capacity, bromination alters the pKa of guanosine from 9.3 to 8.4 (50), but this is likely to be insignificant.

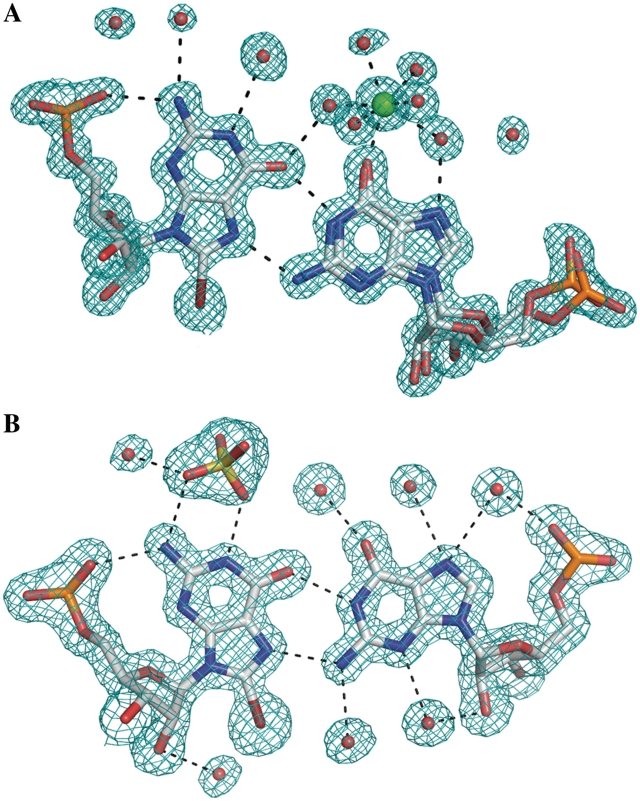

Solvent interactions and hydration

The exposed Watson–Crick edges of G(syn) residues interact with sulphate anions. In some instances in the native RNA structure and in the longer modified duplex, the sulphate appears well ordered, but in most cases its orientation is poorly defined. The anions can be distinguished from water molecules by the size and shape of the electron density and the interaction distance from the RNA (Figure 4b). In the high resolution structure, where there was no sulphate in the crystallization medium, an inner complex is observed involving the carbonyl oxygen atom with a hydrated calcium cation (Figure 4a). The conditions in the crystallization medium are far from physiological, nevertheless the observed complexes indicate a potential of the solvent-exposed Hoogsteen–Watson–Crick edge for attracting charged species, especially as no interactions with ions are observed elsewhere in the structures. In the absence of sulphate, the G(syn) Watson–Crick edge is hydrated by three water molecules that form a crest co-planar with the guanine. In the absence of Ca2+, the G(anti) H-edge is hydrated by two- or three-ordered water molecules.

Figure 4.

The hydration of G(syn)–G(anti) pairs in the GC(8-BrG)GCGGC (A) and in the GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC (B) structures. Ca2+ (green) is bound directly to the carbonyl oxygen atom of G(anti); a sulphate anion interacts with the WC edge of G(syn). The 2Fo-Fc electron density map is contoured at 1σ level.

Interestingly, in all the examined instances of the structure which have sulphate anions in the major groove, the width of the grooves are similar and close to 18 Å (see above), as opposed to the Ca2+-containing structure, in which the groove is narrower by nearly 4 Å. It is possible that the presence of the anions stabilizes the width of the major groove.

Electrostatic surface potential

The electrostatic surface potential shows the already familiar pattern of alternating stripes of positive and negative potential in the minor groove, similar to the previously observed distribution in CUG and CAG repeats (Figure 5). The pattern is due primarily to the C–G and G–C pairs rather than to the interposed N–N pairs. The major groove in the CGG structures is mostly electronegative with positive areas generated each by the Watson–Crick edge of G(syn) and the exo-amino group of the preceding cytidine residue. The binding of the sulphate ions corresponds very closely with the electropositive features associated with G(syn) residues and their calculated surface potential indeed appears higher than for the adjacent cytosines, which have not attracted any ions. The difference in binding potential for ligands can be explained by the exposed Watson–Crick edge of the guanine in this position. In addition, the guanines have stacking interactions only on one side, while the cytosines are engaged on both their surfaces.

Figure 5.

The electrostatic surface potential of two consecutive duplexes of the [GC(8-BrG)GCGGCGGC]2 structure. Red is negative, blue is positive. Sulphate anions (sticks) are shown interacting in the major groove.

It is harder to explain, just by examining the electrostatic potential, what distinguishes CGG from CUG or CAG, and why CGG is not recognized by MBNL1 protein (51–53). An answer could lie in the stability of the CGG duplex. The non-canonical G–G pair contains two H-bonds, as opposed to a single bond in U–U and a weak C–H···N bond in A–A. Therefore the CGG tracts could be more stable in the duplex form and less accessible to the protein which appears to bind single-stranded RNA (54). This is consistent with thermodynamic parameters: ΔG of duplexes containing CGG is markedly higher than for the other three repeats, which are similar (18,19,21).

CONCLUSIONS

This is a third in a series of studies aimed at profiling CNG structures at crystallographic resolution to facilitate drug design and provide 3D templates for rationalizing biochemical and cytological observations. The need for detailed RNA structures is clearly signalled in the literature on rational design of CNG-binding ligands (55–57).

The crystal structures presented here of unmodified and modified CGG repeats are consistent and allow a general description of double-stranded CGG tracts and a comparison with CUG and CAG structures reported previously (29,31). The foremost common feature is that all the known CNG structures form A-helices stabilized by C–G and G–C pairs acting as sturdy struts. The variety is provided in between by the non-canonical pairs.

The ‘accommodation problem’ is solved differently for each N–N pair, but in every case the disruption of the helix is surprisingly small. The bulky guanines fit within the helical constraints by a 180° flip about the glycosidic bond of one of the bases. The equally bulky adenines retain the anti-conformation, but are shifted out of the helical axis, towards the major groove. In the one known example of paired pyrimidines, the relatively small uracil rings remain some distance apart, making only one direct hydrogen bond instead of two bonds which they can make in different environments.

Despite the general resilience of the A-form, characteristic differences can be observed between the CNG duplex structures. The parameters that seem to be specially sensitive are helical twist and major groove width. In CGG helices, we observe local unwinding of the helix around the G–G pairs, as opposed to the more general unwinding in the case of CAG structures. The major groove width may depend on the nature of the ligand which occupies it, bound to the G–G pair. This work provides examples of bound calcium and sulphate ions; another example of sulphate interacting with G–G pairs and possible affecting the groove width is provided by Adamiak and colleagues (58).

Thermodynamic stability is an important property that is difficult to investigate in crystallography, but some measure is provided by the nature and the count of hydrogen bonds and the extent of stacking interactions. In this respect, CGG helical structures appear relatively stable compared with CAG and CUG tracts—in agreement with calorimetric studies (19,21). This could be an important factor in the RNA’s ligand binding affinity and specificity.

So far, the three known CNG repeats have been observed to bind small ligands in the major groove. Glycerol, sulphate anion and Ca2+ cations were found to be associated with N–N pairs of the CNG duplexes. The interactions depend on hydrogen bonds formed with the functional groups exposed in the major groove, characteristic of each N–N pair and to some extent on the electrostatic charge distribution. These can be taken as the main indicators in designing specific ligands.

A detailed comparison of CGG, CAG and CUG duplex structures is provided in Supplementary Table 6.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

3R1C, 3R1D, 3R1E.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Poland, N-N301-0171634); the EU structural funds (POIG.01.03.01-30-098/08); the European Community – Research Infrastructure Action under the FP6 ‘Structuring the European Research Area’ Programme (through the ‘Integrated Infrastructure Initiative’ Integrating Activity on Synchrotron and Free Electron Laser Science – Contract R II 3-CT-2004-506008); Fellowship of the Foundation for Polish Science (to R.K.); Scholarship START of the Foundation for Polish Science (to A.K.). Funding for open access charge: Research grant from Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Poland).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Kozlowski P, de Mezer M, Krzyzosiak WJ. Trinucleotide repeats in human genome and exome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4027–4039. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Richards S, Verkerk AJ, Holden JJ, Fenwick RG, Jr, Warren ST, et al. Variation of the CGG repeat at the fragile X site results in genetic instability: resolution of the Sherman paradox. Cell. 1991;67:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dombrowski C, Levesque S, Morel ML, Rouillard P, Morgan K, Rousseau F. Premutation and intermediate-size FMR1 alleles in 10572 males from the general population: loss of an AGG interruption is a late event in the generation of fragile X syndrome alleles. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:371–378. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong N, Ju W, Pietrofesa J, Wang D, Dobkin C, Brown WT. Fragile X “gray zone” alleles: AGG patterns, expansion risks, and associated haplotypes. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1996;64:261–265. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960809)64:2<261::AID-AJMG5>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagerman RJ, Leehey M, Heinrichs W, Tassone F, Wilson R, Hills J, Grigsby J, Gage B, Hagerman PJ. Intention tremor, parkinsonism, and generalized brain atrophy in male carriers of fragile X. Neurology. 2001;57:127–130. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacquemont S, Hagerman RJ, Leehey M, Grigsby J, Zhang L, Brunberg JA, Greco C, Des Portes V, Jardini T, Levine R, et al. Fragile X premutation tremor/ataxia syndrome: molecular, clinical, and neuroimaging correlates. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:869–878. doi: 10.1086/374321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherman SL. Premature ovarian failure among fragile X premutation carriers: parent-of-origin effect? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:11–13. doi: 10.1086/302985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass IA. X linked mental retardation. J. Med. Genet. 1991;28:361–371. doi: 10.1136/jmg.28.6.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Taylor AK, Gane LW, Godfrey TE, Hagerman PJ. Elevated levels of FMR1 mRNA in carrier males: a new mechanism of involvement in the fragile-X syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;66:6–15. doi: 10.1086/302720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenneson A, Zhang F, Hagedorn CH, Warren ST. Reduced FMRP and increased FMR1 transcription is proportionally associated with CGG repeat number in intermediate-length and premutation carriers. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1449–1454. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sellier C, Rau F, Liu Y, Tassone F, Hukema RK, Gattoni R, Schneider A, Richard S, Willemsen R, Elliott DJ, et al. Sam68 sequestration and partial loss of function are associated with splicing alterations in FXTAS patients. EMBO J. 2010;29:1248–1261. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwahashi CK, Yasui DH, An HJ, Greco CM, Tassone F, Nannen K, Babineau B, Lebrilla CB, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. Protein composition of the intranuclear inclusions of FXTAS. Brain. 2006;129:256–271. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greco CM, Hagerman RJ, Tassone F, Chudley AE, Del Bigio MR, Jacquemont S, Leehey M, Hagerman PJ. Neuronal intranuclear inclusions in a new cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome among fragile X carriers. Brain. 2002;125:1760–1771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Primerano B, Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman P, Amaldi F, Bagni C. Reduced FMR1 mRNA translation efficiency in fragile X patients with premutations. RNA. 2002;8:1482–1488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen LS, Tassone F, Sahota P, Hagerman PJ. The (CGG)n repeat element within the 5′ untranslated region of the FMR1 message provides both positive and negative cis effects on in vivo translation of a downstream reporter. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:3067–3074. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Rubeis S, Bagni C. Fragile X mental retardation protein control of neuronal mRNA metabolism: Insights into mRNA stability. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2010;43:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Napierala M, Michalowski D, de Mezer M, Krzyzosiak WJ. Facile FMR1 mRNA structure regulation by interruptions in CGG repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:451–463. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobczak K, de Mezer M, Michlewski G, Krol J, Krzyzosiak WJ. RNA structure of trinucleotide repeats associated with human neurological diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5469–5482. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobczak K, Michlewski G, de Mezer M, Kierzek E, Krol J, Olejniczak M, Kierzek R, Krzyzosiak WJ. Structural diversity of triplet repeat RNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:12755–12764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zumwalt M, Ludwig A, Hagerman PJ, Dieckmann T. Secondary structure and dynamics of the r(CGG) repeat in the mRNA of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene. RNA Biol. 2007;4:93–100. doi: 10.4161/rna.4.2.5039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broda M, Kierzek E, Gdaniec Z, Kulinski T, Kierzek R. Thermodynamic stability of RNA structures formed by CNG trinucleotide repeats. Implication for prediction of RNA structure. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10873–10882. doi: 10.1021/bi0502339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khateb S, Weisman-Shomer P, Hershco I, Loeb LA, Fry M. Destabilization of tetraplex structures of the fragile X repeat sequence (CGG)n is mediated by homolog-conserved domains in three members of the hnRNP family. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4145–4154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khateb S, Weisman-Shomer P, Hershco-Shani I, Ludwig AL, Fry M. The tetraplex (CGG)n destabilizing proteins hnRNP A2 and CBF-A enhance the in vivo translation of fragile X premutation mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5775–5788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ofer N, Weisman-Shomer P, Shklover J, Fry M. The quadruplex r(CGG)n destabilizing cationic porphyrin TMPyP4 cooperates with hnRNPs to increase the translation efficiency of fragile X premutation mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2712–2722. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Napierala M, Krzyzosiak WJ. CUG repeats present in myotonin kinase RNA form metastable “slippery” hairpins. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31079–31085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michlewski G, Krzyzosiak WJ. Molecular architecture of CAG repeats in human disease related transcripts. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340:665–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobczak K, Krzyzosiak WJ. Imperfect CAG repeats form diverse structures in SCA1 transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41563–41572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sobczak K, Krzyzosiak WJ. CAG repeats containing CAA interruptions form branched hairpin structures in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:3898–3910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiliszek A, Kierzek R, Krzyzosiak WJ, Rypniewski W. Structural insights into CUG repeats containing the ‘stretched U-U wobble’: implications for myotonic dystrophy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4149–4156. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mooers BH, Logue JS, Berglund JA. The structural basis of myotonic dystrophy from the crystal structure of CUG repeats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16626–16631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiliszek A, Kierzek R, Krzyzosiak WJ, Rypniewski W. Atomic resolution structure of CAG RNA repeats: structural insights and implications for the trinucleotide repeat expansion diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:8370–8376. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proctor DJ, Kierzek E, Kierzek R, Bevilacqua PC. Restricting the conformational heterogeneity of RNA by specific incorporation of 8-bromoguanosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2390–2391. doi: 10.1021/ja029176m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia T, SantaLucia J, Jr, Burkard ME, Kierzek R, Schroeder SJ, Jiao X, Cox C, Turner DH. Thermodynamic parameters for an expanded nearest-neighbor model for formation of RNA duplexes with Watson-Crick base pairs. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14719–14735. doi: 10.1021/bi9809425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otwinowski ZM, W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–325. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheldrick GM. Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:479–485. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909038360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cowtan K. An automated procedure for phase improvement by density modification. Joint CCP4 and ESF-EACBM Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1994;31:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamzin VS, Wilson KS. Automated refinement of protein models. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1993;49:129–147. doi: 10.1107/S0907444992008886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olson WK, Bansal M, Burley SK, Dickerson RE, Gerstein M, Harvey SC, Heinemann U, Lu XJ, Neidle S, Shakked Z, et al. A standard reference frame for the description of nucleic acid base-pair geometry. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:229–237. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jo S, Vargyas M, Vasko-Szedlar J, Roux B, Im W. PBEQ-Solver for online visualization of electrostatic potential of biomolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W270–W275. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Palo Alto, CA, USA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burkard ME, Turner DH. NMR structures of r(GCAGGCGUGC)2 and determinants of stability for single guanosine-guanosine base pairs. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11748–11762. doi: 10.1021/bi000720i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burkard ME, Xia T, Turner DH. Thermodynamics of RNA internal loops with a guanosine-guanosine pair adjacent to another noncanonical pair. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2478–2483. doi: 10.1021/bi0012181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.SantaLucia J, Jr, Kierzek R, Turner DH. Stabilities of consecutive A.C, C.C, G.G, U.C, and U.U mismatches in RNA internal loops: Evidence for stable hydrogen-bonded U.U and C.C.+ pairs. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8242–8251. doi: 10.1021/bi00247a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leontis NB, Westhof E. Geometric nomenclature and classification of RNA base pairs. RNA. 2001;7:499–512. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haran TE, Wang AH-J, Rich A. The crystal structure of d(CCCCGGGG): a new A-form variant with an extended backbone conformation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1987;2:397–412. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1987.10506390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ioele M, Bazzanini R, Chatgilialoglu C, Mulazzani QG. Chemical Radiation Studies of 8-Bromoguanosine in Aqueous Solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:1900–1907. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ho TH, Savkur RS, Poulos MG, Mancini MA, Swanson MS, Cooper TA. Colocalization of muscleblind with RNA foci is separable from mis-regulation of alternative splicing in myotonic dystrophy. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:2923–2933. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kino Y, Mori D, Oma Y, Takeshita Y, Sasagawa N, Ishiura S. Muscleblind protein, MBNL1/EXP, binds specifically to CHHG repeats. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:495–507. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan Y, Compton SA, Sobczak K, Stenberg MG, Thornton CA, Griffith JD, Swanson MS. Muscleblind-like 1 interacts with RNA hairpins in splicing target and pathogenic RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5474–5486. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teplova M, Patel DJ. Structural insights into RNA recognition by the alternative-splicing regulator muscleblind-like MBNL1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:1343–1351. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arambula JF, Ramisetty SR, Baranger AM, Zimmerman SC. A simple ligand that selectively targets CUG trinucleotide repeats and inhibits MBNL protein binding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16068–16073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901824106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee MM, Childs-Disney JL, Pushechnikov A, French JM, Sobczak K, Thornton CA, Disney MD. Controlling the specificity of modularly assembled small molecules for RNA via ligand module spacing: targeting the RNAs that cause myotonic muscular dystrophy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17464–17472. doi: 10.1021/ja906877y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pushechnikov A, Lee MM, Childs-Disney JL, Sobczak K, French JM, Thornton CA, Disney MD. Rational design of ligands targeting triplet repeating transcripts that cause RNA dominant disease: application to myotonic muscular dystrophy type 1 and spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9767–9779. doi: 10.1021/ja9020149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rypniewski W, Adamiak DA, Milecki J, Adamiak RW. Noncanonical G(syn)-G(anti) base pairs stabilized by sulphate anions in two X-ray structures of the (GUGGUCUGAUGAGGCC) RNA duplex. RNA. 2008;14:1845–1851. doi: 10.1261/rna.1164308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.