Abstract

Flies with mutations in the single Drosophila Adar gene encoding an RNA editing enzyme involved in editing 4% of all transcripts have severe locomotion defects and develop age-dependent neurodegeneration. Vertebrates have two ADAR-editing enzymes that are catalytically active; ADAR1 and ADAR2. We show that human ADAR2 rescues Drosophila Adar mutant phenotypes. Neither the short nuclear ADAR1p110 isoform nor the longer interferon-inducible cytoplasmic ADAR1p150 isoform rescue walking defects efficiently, nor do they correctly edit specific sites in Drosophila transcripts. Surprisingly, human ADAR1p110 does suppress age-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila Adar mutants whereas ADAR1p150 does not. The single Drosophila Adar gene was previously assumed to represent an evolutionary ancestor of the multiple vertebrate ADARs. The strong functional similarity of human ADAR2 and Drosophila Adar suggests rather that these are true orthologs. By a combination of direct cloning and searching new invertebrate genome sequences we show that distinct ADAR1 and ADAR2 genes were present very early in the Metazoan lineage, both occurring before the split between the Bilateria and Cnidarians. The ADAR1 gene has been lost several times, including during the evolution of insects and crustacea. These data complement our rescue results, supporting the idea that ADAR1 and ADAR2 have evolved highly conserved, distinct functions.

INTRODUCTION

The conversion of adenosine (A) to inosine (I) by RNA editing occurs in CNS transcripts in both Drosophila and humans, diversifying ion channels and many other proteins [for reviews see (1,2)]. The ADAR RNA editing enzymes recognize specific adenosines within RNA duplexes that form, typically by base pairing between edited exons and sequences in adjacent introns, in edited transcripts. ADARs have two or more double-stranded (ds) RNA binding domains that bind dsRNA (3), and a catalytic deaminase domain that also contributes to recognition of bases adjacent to the edited site (Figure 1A). Although the ADAR RNA editing enzymes are conserved, the editing events in particular transcripts are not; edited transcripts differ substantially between fly and human and no clear example of a conserved editing site has been found. In Drosophila editing is extensive. A recent study identified 972 edited positions within transcripts of 597 genes, 630 of which are predicted to alter protein-coding sequences (4) It is not known which editing events are responsible for the Adar phenotype (5,6). Other invertebrates such as the squid, a member of the Phylum Mollusca, also show extensive RNA editing of CNS transcripts (7–10). Vertebrates have far fewer editing events that result in recoding of transcripts and only one editing event is essential (11). One recent study identified 239 edited sites in 207 human transcripts, but only 38 are predicted to change codons (12).

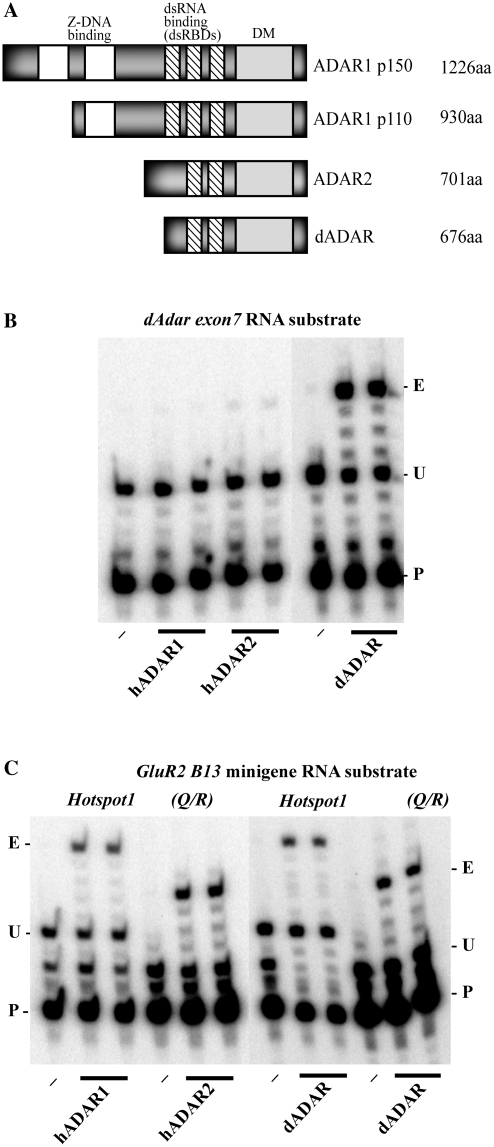

Figure 1.

Comparison of human and Drosophila ADAR structures and activities on RNA substrates in vitro. (A) Domain structures of human and Drosophila ADARs. (B) In vitro RNA editing of a single site in the Drosophila Adar exon 7 substrate by duplicate samples of Drosophila and human ADARs analysed by poisoned primer extension with dideoxythymidine. Dash indicates substrate RNA incubated without ADAR. For each primer extension reaction P (primer) indicates the end-labelled primer, U, (unedited) indicates the position of the next A after the primer in the template. On unedited templates primer extension terminates at the first A but if this is edited then primer extension continues to the next A, which is indicated with E, (edited). (C) In vitro RNA editing of two sites in the mammalian GluR-2 miniB 13 substrate by Drosophila and human ADARs analysed with poisoned primer extension with dideoxythymidine. The GluR-2 miniB 13 transcript contains an exonic Q/R editing site (unextended primer and unedited and edited extension product sizes indicated on the right) that is preferentially edited by human ADAR2 and an intronic hotspot site (primer and extension product sizes on the left) that is preferentially edited by human ADAR1.

Mutations to both Drosophila and vertebrate ADAR genes have catastrophic effects on the CNS. Drosophila has a single Adar gene and mutations cause a loss of locomotion in adult flies from birth and drastic age-dependent neurodegeneration (13,14). Vertebrates have two catalytically active ADAR genes and mutations in one of them, the CNS-expressed Adar2 gene, leads to seizures and early postnatal death with localized hippocampal neurodegeneration in mice (11). The mouse Adar2 mutant is rescued by genomically encoding a single residue change in a key AMPA class glutamate receptor subunit transcript that is normally introduced by editing. By replacing a glutamine (Q) codon with an arginine (R) codon within the region of GluR2 transcripts that encodes the ion channel pore, Adar2 mutant mice survive to adulthood. Editing at this site has the key functions of both restraining the assembly of AMPA receptors to synapses and blocking calcium entry through the resulting channels (15,16). Reductions in RNA editing efficiency at this site leads to production of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors and may be involved in disease symptoms such as motor neuron death through glutamate excitotoxicity in ALS (17), and selective neuron death following ischaemia in stroke (18).

Vertebrates have two other ADAR genes; ADAR1 is widely expressed within the CNS as well as in mesoderm and haematopoietic lineages. Mutations in Adar1 result in death of mouse embryos by embryonic day 12.5 with failure of haematopoiesis in the liver and overproduction of interferon (19–21), preventing the role of Adar1 in the CNS from being assessed. ADAR1 has an intrinsic RNA editing site specificity that is distinct from that of ADAR2, however to date no site-specific editing event catalysed by ADAR1 has been found to be essential. This enzymatic substrate specificity is surprising considering the overall homology between the two proteins and also that the major groove in the A structure of dsRNA is inaccessible, rendering it difficult for proteins to read the actual base sequence of dsRNA substrates (22). Selection of particular adenosines for editing at different RNA editing sites is likely to be determined by the location of the edited base within the duplex and by its proximity to imperfect pairings between base pairs in each duplex structure (3). In addition both ADAR1 and ADAR2 have distinct yet overlapping preferences for particular nucleotides 5′ and 3′ of the editing sites when editing long dsRNA (23,24). There is some evidence of competition between ADAR1 and ADAR2 in editing: in neurons cultured from Adar1−/− ES cells loss of ADAR1 leads to increases in RNA editing by ADAR2 at some sites in transcripts encoding 5-HT2C receptor (19,20).

Until recently the single Drosophila Adar gene appeared to be an invertebrate ancestor of both human ADARs and we wondered if it had similar or distinct substrate specificity to the human ADARs. As the edited sites in target transcripts are not conserved, the ADARs may also have diverged in their substrate specificities. We investigated this with RNA editing assays in vitro and by expressing the human ADARs in Drosophila, to determine if they can edit Drosophila transcripts, rescue locomotion defects and suppress neurodegeneration. It is advantageous to perform this analysis in Drosophila as there are a large number of editing sites in the fly to compare the editing site specificities of the different ADARs.

Surprisingly, we find that the editing specificity of an ADAR2-type protein is conserved from fly to human, allowing effective rescue of site-specific RNA editing events, locomotion defects and suppression of neurodegenerative phenotypes in Adar mutant flies by human ADAR2. ADAR1 does not efficiently edit most sites in Drosophila transcripts nor does it rescue the locomotion phenotype. However the different ADAR1 isoforms behave differently with regard to the neurodegeneration phenotype; ADARp110 suppress neurodegeneration whereas ADAR1p150 does not.

We conclude that Drosophila Adar is an orthologue of vertebrate ADAR2. By cloning ADAR genes from invertebrates and by examining data from genome sequencing projects, particularly that of the starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis (25), we show that ADAR1 and ADAR2 have evolved independently since early in Metazoan evolution. Both ADAR1 and ADAR2 genes are present in molluscs, annelids, echinoderms and even cnidarians. ADAR1 appears to have been lost in some Arthropods, including insects, as well as in some other taxa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Comparison of RNA editing site specificities of Drosophila and vertebrate ADARs in vitro

All recombinant ADAR proteins were expressed and purified from Pichia pastoris as previously described (26). Poisoned primer extension assays in the presence of dideoxythymidine were performed with equivalent concentrations of ADAR proteins as described in (27).

Rescue of Adar mutant phenotypes in Drosophila by human ADAR1 and ADAR2

cDNAs encoding full length human ADARs were cloned into the vector pUAST and multiple balanced transgenic Drosophila lines were generated with constructs inserted randomly at different locations on Chromosomes II or III. These construct lines were crossed to lines expressing GAL4 ubiquitously and strongly in all cells [actin 5C-GAL4 25FO1 driver (28)], or strongly in cholinergic neurons [Cha-GAL4 19B, UAS-GFP S65T driver (29) also expressing an enhanced GFP from Chr. II]. To express ADARs in an Adar5G1 mutant background under the control of the Cha-GAL4 driver, for example, we crossed the UAS-ADAR lines to females of a strain that had the first and second chromosome genotypes y, Adar5G1, w/w, FM6 Bar; Cha-GAL4 / SM5 Cy and picked male y, Adar5G1, w; Cha-GAL4, UAS-ADAR progeny to measure rescue of mutant phenotypes.

We also constructed a strain that had the first and second chromosome genotypes y, Adar5G1, w /w, FM6 Bar; UAS-dADAR S / SM5 Cy. This strain has no GAL4 driver but it allows the rescue effectiveness of drivers expressing GAL4 in different cell types to be tested. Crossing males of some GAL4 driver lines to females of this strain gives male y, Adar5G1, w; GAL4 driver; UAS-Adar S progeny in which phenotypes are rescued by expression of the UAS-dAdar S construct in particular cell types.

Open field locomotion assay

We measured phenotypic rescue of Adar1F4 and Adar5G1 locomotion defects with an open field locomotion assay on flies expressing the human UAS-ADAR constructs 2–4 days after eclosion (30). Flies were collected using CO2 and left for 1 day to recover before performing this assay. They were placed in a 30-mm petri dish divided into seven equal areas. The dishes were tapped and the number of times a fly walked over a line separating the zones was recorded for a 2-min period. This was then repeated a further two times for each individual fly. For each UAS-ADAR construct multiple different transgenic lines with random insertions were generated to control for variations in expression levels due to insertion sites. Locomotion rescue was measured for 10 or more flies from each of three different transgenic lines for each construct. RNA editing in vivo and protein expression levels were determined for the line of each construct that rescued locomotion best or that showed the darkest red eye colour, another correlate of expression levels at different sites of chromosomal insertion.

Other Drosophila GAL4 driver lines used in this study

w1118; Ddc-Gal4 L 4.3D on Chr. II expresses GAL4 in the pattern of dopa decarboxylase which is involved in synthesis of the excitatory neurotransmitter dopamine in dopaminergic neurons. Tdc2-GAL4 C 2 on Chr. III expresses GAL4 in the pattern of tyrosine decarboxylase which is involved in synthesis of the excitatory neurotransmitter octopamine in octopaminergic neurons. Expression of two of the three motor neurone driver lines have been examined in detail elsewhere (31). The OK6 line has a GAL4 enhancer trap insertion in the Rapgap1 gene on Chr. II and is the driver line most highly specific for motor neurones. The D42 line is a GAL4 enhancer trap insertion in the toll6 gene on Chr. III (31). It is expressed in a very small number of brain cells and in peripheral nervous system in addition to motor neurones. w1118; VGlutOK371 has a GAL4 enhancer trap insertion on Chr. II in the gene encoding the vesicular glutamate vesicular uptake receptor (32), broadly expressed in all glutamatergic neurons including motor neurons. w1118; OK307 is a GAL4 enhancer trap insertion on Chr. II that is expressed specifically in the giant fibre descending jump escape neuron.

Haematoxylin and eosin staining

To characterize neurodegeneration 6-µm sections of paraffin wax-embedded Adar5G1 mutant heads were cut and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. To remove the wax the slides were taken through three 5-min incubations in Xylene. To re-hydrate, the slides were incubated twice in 100% ethanol for 2 min, 90% ethanol for 2 min, 80% ethanol for 2 min, 50% ethanol for 2 min, 30% ethanol for 2 min and finally in H2O for 2 min. The slides were incubated in freshly filtered haematoxylin for 4 min and then in running tap water. Once the haematoxylin had washed out the slides were dipped twice into acid alcohol and again washed in running tap water. The slides were incubated in lithium carbonate for 3 min and then in water for 3 min. The slides were incubated in 1% eosin for 4 min and quickly washed in running tap water. The slides were dipped in 100% ethanol and then incubated three times in 100% ethanol each for 2 min. Before mounting the slides were incubated in Xylene three times, each for 5 min. The slides were mounted with D.P.X. and eyes were photographed at 40× and mushroom bodies at 63× with Zeiss Plan Neofluor objectives on a Zeiss Axiophot compound microscope with Coolsnap HQ CCD camera (Photometrics Ltd. Tuscon, AZ, USA) and images processed using IPLab Spectrum (Scanalytics Corp, Fairfax VA, USA) with all alterations of brightness and contrast covering the entire image.

Oligos, RT–PCR and sequencing

The oligos used in this study to perform RT–PCR and for sequencing the edited positions are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Quantitating RNA editing activity in vivo

RNA was extracted from rescue and control male flies with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer and sequential RT–PCR was performed on the isolated RNA. To ensure that each RT–PCR product sequenced represents a distinct initial first strand cDNA, two separate RT reactions were performed. The majority of the editing sites were analysed by sequencing the RT–PCR reaction product pools and not by sequencing individual clones. We measured the relative heights of A and G peaks in electropherograms of RT–PCR product pools covering edited sites. Editing at each site was determined using multiple sequence chromatograms in each direction. To indicate the variability in this data: for percentage editing in adult male flies at Eag 2107 Y/C in Table 1 the standard error is ±2% flies and for editing at Eag 2159 V/V the standard error is ±2.9%. If editing appeared to be zero at a position but there was a low background in the electropherogram then we inserted an asterisk in the tables to represent this.

Table 1.

Percentage RNA editing at specific sites in transcripts isolated from whole wildtype Canton S male or female flies, embryos and third instar larvae

| Male | n | Female | n | Embryo | n | Larva | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caα1D | ||||||||

| 2061 L/L | 36 | 4 | 38 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| 2083 N/D | 97 | 4 | 95 | 4 | 22 | 6 | 20 | 3 |

| 2097 L/L | 96 | 4 | 89 | 4 | a | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| 2098 R/G | 96 | 4 | 92 | 4 | a | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| 2140 I/M | 100 | 2 | 100 | 4 | 14 | 6 | 18 | 3 |

| Eag | ||||||||

| 1864 K/R | 58 | 11 | 66 | 4 | 76 | 2 | 89 | 3 |

| 2107 Y/C | 89 | 11 | 92 | 5 | 46 | 3 | 70 | 5 |

| 2159 V/V | 16 | 7 | a | 5 | 0 | 3 | a | 4 |

| 2163 N/D | 88 | 7 | 86 | 5 | 52 | 3 | 66 | 4 |

| 2560 K/R | 78 | 3 | 60 | 2 | a | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Nic 34E | ||||||||

| 1872 L/L | 100 | 6 | 76 | 4 | 85 | 4 | 100 | 4 |

| 1873 I/V | 100 | 6 | 78 | 4 | 85 | 4 | 100 | 4 |

| 2020 T/A | 100 | 7 | 97 | 6 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 3 |

| 2023 I/V | 38 | 5 | 30 | 5 | 16 | 4 | 17 | 3 |

| 2028 L/L | 35 | 5 | 28 | 3 | 15 | 2 | 15 | 3 |

| 2037 I/M | 67 | 5 | 60 | 3 | 41 | 2 | 48 | 3 |

| 2049 L/L | 16 | 4 | 17 | 3 | 0 | 2 | a | 3 |

| 2052 S/S | 71 | 4 | 63 | 1 | 40 | 1 | 40 | 3 |

| 2062 I/V | 100 | 4 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 3 |

| 2065 I/V | 53 | 4 | 41 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 11 | 3 |

| Rdl | ||||||||

| 728 L/L | 23 | 8 | 23 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 735 R/G | 65 | 8 | 68 | 4 | 0 | 2 | a | 2 |

| 1218 I/V | 100 | 8 | 87 | 8 | 78 | 2 | 100 | 2 |

| 1251 N/D | 22 | 4 | 14 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 1448 Q/Q | 8 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1449 M/V | 22 | 4 | 20 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

The left column lists the specific editing sites in target transcripts and the bold numbers indicate the percentage editing at that site in the different samples. The total number of RT–PCR reactions sequenced is represented by n.

aEditing is probably 0 however due to background in sequencing electropherogram 0 cannot be assigned to this position.

Phylogenetic analysis of invertebrate ADAR1 and ADAR2

Putative ADAR sequences were identified using blast searches (tblastn or blastp) against invertebrate genome sequences available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/genom_table.cgi?organism=euk) and the Joint Genome Institute (JGI- (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/). Initially human ADAR1 and ADAR2 were used as query sequences. As we identified invertebrate homologues, they were used as queries as well. Cephalopod ADAR deaminase domains were cloned directly using cDNA samples and PCR primers based on other invertebrate ADAR sequences. Putative ADAR hits were defined as ADAR1 or ADAR2 using several criteria. First, the core deaminase domains were aligned with vertebrate ADAR1 and ADAR2 using T-COFFEE (http://tcoffee.vital-it.ch/cgi-bin/Tcoffee/tcoffee_cgi/index.cgi) to assess general homology with residues previously defined as ADAR1 or ADAR2 consensus. Second, phylogenetic trees were generated using the entire deaminase domain. Alignments for ADAR1 and ADAR2 were generated using M-COFFEE (http://tcoffee.vital-it.ch/cgi-bin/Tcoffee/tcoffee_cgi/index.cgi). Both alignment files were joined by ClustalX2 (profile mode). Gap-rich columns were removed from each alignment. The tree was generated using Phylip Package (Protdist, Neighbor, Consense) (http://bioweb.pasteur.fr/phylogeny/intro-en.html). In the following cases only partial sequences were available; Varroa destructor (ADAR1 and ADAR2), Helobdella robusta (ADAR1), Acropora millepora (ADAR1) See Supplementary Table S2 for the names of species in different evolutionary groups and for sequence accession numbers. For these, separate phylogenetic trees were generated using the homologous regions from both human ADAR1 and ADAR2. Based on these trees the partial sequences were classified as either ADAR1 or ADAR2. All the accession numbers for ADAR1 and ADAR2 that were used in the alignment are in Supplementary Table S2.

RESULTS

Human ADAR1 and ADAR2 proteins show greater selectivity than Drosophila ADAR for specific sites in vitro

Human ADAR1 and ADAR2 proteins (Figure 1A), have been shown to have distinct editing site specificities for vertebrate transcripts. Using an in vitro poisoned primer extension assay in the presence of dideoxythymidine we compared the specific RNA editing activities of dADAR 3/4, human ADAR1p110 and human ADAR2 proteins on the Adar exon 7 substrate from Drosophila which dADAR edits very efficiently in vitro (30) (Figure 1B) and on the GluR2 B13 minigene substrate (Figure 1C). Fly and human ADAR proteins expressed in the yeast Pichia pastoris were purified and cross-species editing was tested using equivalent amounts of the different proteins sufficient for maximal editing of their specific substrates.

The vertebrate proteins are much less active on the Drosophila Adar exon 7 substrate than dADAR 3/4 is. Human ADAR2 edits the Adar exon7 site slightly more efficiently than human ADAR1p110, but the activity is significantly lower than that of Drosophila ADAR (Figure 1B). This data is in agreement with what was previously observed when all three enzymes were assayed on long dsRNA for promiscuous RNA editing and dADAR edited more sites than the two human proteins (24).

The dADAR 3/4 protein edits sites in the vertebrate substrate efficiently (Figure 1C). The GluR2 B13 minigene substrate contains an exonic Q/R editing site that is preferentially edited by human ADAR2 and an intronic hotspot site that is preferentially edited by human ADAR1 (27,33). Drosophila ADAR is less selective than the human ADARs on the GluR2 B13 minigene substrate, efficiently editing both the Q/R (ADAR2-preferred) site and the hotspot (ADAR1-preferred) site.

Because relatively few of the dsRNA structures that are required for editing have been fully defined in Drosophila, only a limited number of site-specific RNA editing events can be assayed in vitro. Since Drosophila has so many edited transcripts, a much larger number of edited sites can be studied in vivo in transgenic flies. By expressing human ADAR proteins we can elucidate if some Drosophila editing sites respond to human ADARs differently than the dAdar exon7 site.

Human ADAR2 rescues locomotion defects in Adar mutant Drosophila

Constructs designed to express human ADAR cDNAs under UAS/GAL4 control were injected into Drosophila and transgenic lines were generated and balanced. To measure phenotypic rescues, human and Drosophila ADAR proteins were expressed in two different deletion strains of Adar in a range of tissue-specific expression patterns by means of the GAL4-UAS binary system. Both Adar1F4 and Adar5G1 mutants are equally grossly defective in open-field locomotion and totally lack RNA editing in all ion channel transcripts tested (Figure 2) (14). The Adar1F4 deletion removes promoters of Adar but leaves the coding sequence intact and its expression is at least 10- to 20-fold lower (14). This strain shows residual RNA editing at only one identified site—the Adar exon7 site. In later stages of this study we concentrate on the Adar5G1 null mutant, as it completely removes the coding sequence and expresses no ADAR protein. In addition we found age-dependent neurodegeneration proceeds more rapidly in the Adar5G1 null mutant.

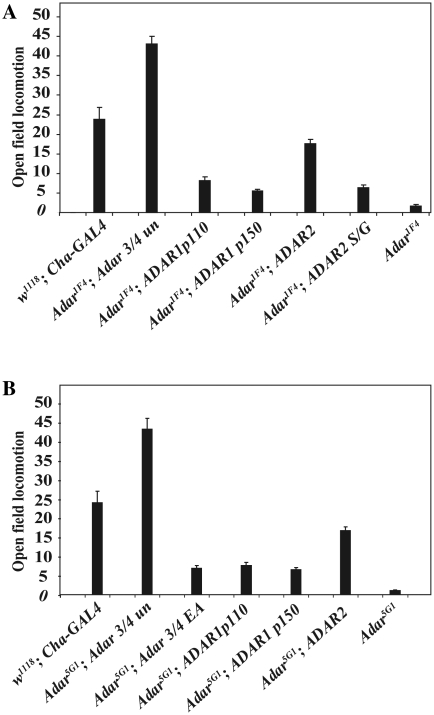

Figure 2.

Human ADAR2 rescues Drosophila Adar mutant locomotion defects. (A) Rescue by human ADAR2 of hypomorphic Adar1F4 mutant open field locomotion defects with the strong neuron-specific Cha-GAL4 driver. Neither the long nucleocytoplasmic shuttling human ADAR1p150 isoform nor the shorter human ADAR1p110 nuclear isoform rescue locomotion defects. (B) Rescue of locomotion in the Adar5G1 null mutant.

Strong and widespread expression of ADAR proteins in both the Adar5G1 and Adar1F4 mutant brains was obtained using the Cha-GAL4 driver: choline acetyl transferase encoded by the Cha gene is involved in the biosynthesis of acetylcholine, the major excitatory neurotransmitter in insect neurons. Because the Drosophila Adar gene is on the X chromosome, rescue phenotypes were measured in male flies that had the Adar mutation and that also had the Cha-GAL4 driver construct and UAS-ADAR constructs.

Each of the two vertebrate ADARs yield viable flies when expressed under the control of the Cha-GAL4 driver. Figure 2 shows a comparison of open field locomotion tests on Adar1F4 (Figure 2A) or Adar5G1 (Figure 2B) mutant flies that have Drosophila ADAR protein or different vertebrate ADARs expressed under the control of the Cha-GAL4 driver. The Adar mutants are both grossly defective in locomotion and this defect is efficiently rescued by either the Drosophila ADAR 3/4 protein or human ADAR2 in either Adar1F4 or Adar5G1 mutant flies (Figure 2A and B) whereas the rescue with human ADAR1p110 or ADAR1p150 is barely above background and movement is not well coordinated. For each ADAR expressed the locomotion data represents an average of results obtained with three independent insertions of the relevant UAS-ADAR transgene and the results obtained with different insertion lines for each ADAR are consistent with each other. The wild-type control strain is w1118; Cha-GAL4. This is an appropriate control because strong expression of GAL4 in neurons negatively affects locomotion in flies, (w1118 flies cross 57 lines in 2 min in this test.) Expression of ADAR 3/4 restores locomotion above the level seen in w1118; Cha-GAL4 but not quite to the level seen in w1118. Locomotion rescue by ADAR2 is not as strong as expected since it edits most Drosophila sites more efficiently than dADAR 3/4.

ADAR1 is expressed as either a cytoplasmic 150-kDa protein that shuttles in and out of the nucleus but accumulates in cytoplasm or as a shorter 110-kDa protein that is primarily localized to the nucleus (34). Neither isoform efficiently rescues the locomotion defects in either Adar1F4 or Adar5G1 mutant Drosophila (Figure 2A and B). There is a small effect of ADAR1 in improving the locomotion but a similar slight effect is seen with a catalytically inactive mutant form of Drosophila ADAR in which an essential glutamate residue at the catalytic site has been mutated to alanine (dADAR 3/4 EA, Figure 2B). Catalytic RNA editing activity at appropriate target sites is necessary for full locomotion rescue.

The equivalence of function between human ADAR2 and Drosophila Adar is further supported by the fact that ubiquitous expression of UAS-ADAR2 with the actin 5C-GAL4 driver is lethal to Drosophila; similar lethality was previously observed with the very active genome-encoded isoform of dADAR that has a serine residue as found in ADAR2 at the S/G RNA editing site in the deaminase domain (30). The lethality was attributed to premature editing of target transcripts during embryonic development, particularly in muscle tissue or heart which normally have lower ADAR expression than CNS. There is a very much weaker rescue of locomotion when the serine corresponding to the Drosophila self-editing site is mutated to glycine in ADAR2 (Figure 2A). Editing of the GluR2 B13 minigene substrate at the Q/R site is reduced 8-fold by the serine to glycine mutation in poisoned primer extension assays (Supplementary Figure S1). Widespread ADAR1 expression under actin 5C-GAL4 driver control is not fully lethal in Drosophila though viability is low and only small numbers of flies are obtained.

Human ADAR2 edits many Drosophila editing sites similarly to dADAR but ADAR1 edits only a subset of these sites

We do not know which individual RNA editing events or which combination of editing events in the known edited transcripts in Drosophila are the most essential. Therefore we chose to measure RNA editing levels in a subset of the known Drosophila transcripts that contain sites that are highly edited at functionally important amino acids (5). These sites were originally identified by comparative genomics due to strong evolutionary conservation among fly species of exonic sequences flanking some of the highly edited positions due to conservation of RNA duplex formation. We analysed 26 RNA editing sites in four transcripts in embryos, larvae and adult male and female flies to examine developmental RNA editing levels in these transcripts and to determine if there were sex-specific effects (Table 1). Editing levels were calculated using peak height measurements of A and G peaks in sequencing electropherograms of RT–PCR products covering each the edited sites. The analysis shows that amongst this set of transcripts some sites are fully edited such as the 1218 I/V site in the Rdl (Resistance to Dieldrin) transcript which encodes a pore-forming alpha subunit of a member of the inhibitory GABA-gated chloride channel family. Another transcript with fully edited sites, Nic34E, encodes a pore-forming subunit of acetylcholine receptors. Acetylcholine has widespread significance as an excitatory neurotransmitter in insect brain similar to that of glutamate in vertebrate brain.

As previously observed, editing at most sites is low in embryos and increases during development (13,30). There was a dramatic increase in editing of the Caα1D transcript encoding a muscle-type voltage-gated calcium channel that is expressed in both muscle and CNS at metamorphosis. The Nic34E transcript encoding a pore-forming subunit of a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is always highly edited with two sites being edited to 100% even in early developmental stages. We decided that these sites would be informative to analyse rescue of RNA editing by human ADARs since they include sites constitutively edited by dADAR as well as sites with editing levels ranging from 0 to 100%. The constitutive editing of some of these sites throughout development (Table 1), is reminiscent of the human GluR2 Q/R site (35) and also suggests that these editing sites might be physiologically important. Editing of these transcripts was slightly higher in males than females.

We measured RNA editing levels in these transcripts in flies expressing either human ADAR proteins or Drosophila ADAR and compared these to editing levels seen in wild-type Canton S and Adar mutant flies (Tables 2 and 3). Expressing Drosophila ADAR 3/4 under the control of the Cha-GAL4 driver in the Adar5G1 background rescues RNA editing in these sites, substantially though not completely (Table 2). Editing is completely dependent on dADAR as it is eliminated in the Adar5G1 mutant and not restored by expression of a catalytically inactive dADAR 3/4 EA protein (data not shown). Human ADAR2 edits 22/26 sites analysed in Drosophila when expressed using the Cha-GAL4 driver in Adar5G1 (Table 2). The levels of editing at specific sites are generally similar to, and generally higher than, levels obtained for rescue by dADAR expressed under the control of the Cha-GAL4 driver. We have repeated this with different drivers and the pattern of editing with ADAR2 is always similar to that with dADAR. Human ADAR1p110 and p150 display low levels of editing activity, 2/26 and 3/26 sites respectively were edited.

Table 2.

Percentage RNA editing at specific sites in transcripts from rescued Adar5G1 flies expressing either dADAR, hADAR1p110, hADARp150 or hADAR2 under the control of the Cha-GAL4 driver

| WT | n | 5G1 | n | dAdar | n | ADAR2 | n | ADAR1 P110 | n | ADAR1 P150 | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caα1D | ||||||||||||

| 2061 L/L | 36 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 18 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| 2083 N/D | 97 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 4 | 56 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| 2097 L/L | 96 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| 2098 R/G | 96 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 4 | 24 | 4 | 0 | 4 | a | 2 |

| 2140 I/M | 100 | 2 | a | 2 | 0 | 4 | 25 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Eag | ||||||||||||

| 1864 K/R | 58 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 14 | 5 | 10 | 2 | a | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| 2107 Y/C | 89 | 5 | 0 | 11 | 21 | 5 | 36 | 9 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 13 |

| 2159 V/V | 16 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 23 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 13 |

| 2163 N/D | 88 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 52 | 3 | 30 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 13 |

| 2560 K/R | 78 | 2 | a | 3 | a | 1 | 31 | 6 | 0 | 3 | a | 11 |

| Nic 34E | ||||||||||||

| 1872 L/L | 100 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 16 | 2 | 54 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| 1873 I/V | 100 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 14 | 2 | 56 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| 2020 T/A | 100 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 55 | 2 | 79 | 5 | 0 | 3 | a | 3 |

| 2023 I/V | 38 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 2028 L/L | 35 | 1 | a | 5 | 0 | 2 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 2037 I/M | 67 | 1 | a | 5 | 6 | 2 | 49 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 21 | 7 |

| 2049 L/L | 16 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| 2052 S/S | 71 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 18 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| 2062 I/V | 100 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 46 | 2 | 31 | 3 | 0 | 2 | * | 6 |

| 2065 I/V | 53 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 14 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 4 |

| Rdl | ||||||||||||

| 728 L/L | 23 | 2 | a | 8 | a | 6 | 12 | 4 | 10 | 11 | a | 8 |

| 735 R/G | 65 | 2 | a | 8 | 12 | 6 | 39 | 4 | 16 | 11 | a | 8 |

| 1218 I/V | 100 | 3 | a | 8 | 43 | 3 | 81 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 1251 N/D | 22 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 1448 Q/Q | 8 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| 1449 M/V | 22 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

The left column lists the specific editing sites in target transcripts and the bold numbers indicate the percentage editing at that site in the different samples. The total number of RT–PCR reactions sequenced is represented by n.

aEditing is probably 0 however due to background in sequencing electropherogram 0 cannot be assigned to this position.

Table 3.

Percentage RNA editing at specific sites in transcripts from rescued Adar1F4 flies expressing either dADAR, hADAR1p110, hADARp150 or hADAR2 under the control of the Cha-GAL4 driver

| WT | n | 1F4 | n | dAdar | n | ADAR2 | n | ADAR1 P110 | n | ADAR1 P150 | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caα1D | ||||||||||||

| 2061 L/L | 36 | 1 | a | 4 | 13 | 5 | 24 | 4 | 25 | 2 | 29 | 1 |

| 2083 N/D | 97 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 31 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2097 L/L | 96 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 24 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2098 R/G | 96 | 2 | a | 3 | 29 | 5 | 32 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2140 I/M | 100 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 26 | 5 | 20 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Eag | ||||||||||||

| 1864 K/R | 58 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 50 | 2 | 58 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 |

| 2107 Y/C | 89 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 55 | 3 | 56 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 4 |

| 2159 V/V | 16 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 24 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 |

| 2163 N/D | 88 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 62 | 5 | 46 | 6 | 40 | 7 | 12 | 4 |

| 2177 A/A | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | a | 5 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 4 |

| 2560 K/R | 78 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 37 | 2 | 56 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Nic 34E | ||||||||||||

| 1872 L/L | 100 | 4 | 0 | 5 | b | 76 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1873 I/V | 100 | 4 | 0 | 5 | b | 74 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 2020 T/A | 100 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 82 | 3 | 80 | 3 | 26 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 2023 I/V | 38 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 35 | 3 | a | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 2028 L/L | 35 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 29 | 3 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 2037 I/M | 67 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 63 | 3 | 75 | 3 | 84 | 3 | 37 | 1 |

| 2052 S/S | 71 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 60 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 27 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 2062 I/V | 100 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 84 | 3 | 38 | 2 | 32 | 3 | 10 | 1 |

| 2065 I/V | 53 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 42 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 54 | 2 | 17 | 1 |

| Rdl | ||||||||||||

| 728 L/L | 23 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 2 | 34 | 4 | a | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 735 R/G | 65 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 52 | 2 | 64 | 4 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1218 I/V | 100 | 3 | a | 2 | 88 | 2 | 81 | 4 | 31 | 2 | 16 | 2 |

| 1251 N/D | 22 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1448 Q/Q | 8 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1449 M/V | 22 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 2 | a | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

The left column lists the specific editing sites in target transcripts and the bold numbers indicate the percentage editing at that site in the different samples. The total number of RT–PCR reactions sequenced is represented by n.

aEditing is probably 0 however due to background in sequencing electropherogram 0 cannot be assigned to this position.

bSites that we were unable to obtain sequence for.

When the Adar1F4 hypomorphic mutant background is used in rescue experiments with the Cha-GAL4 driver the pattern of locomotion rescue is unchanged from that obtained in the Adar5G1 null background, i.e. ADAR2 rescues and ADAR1 isoforms do not (Figure 2). Levels of RNA editing at most sites are higher in Adar1F4 rescues with UAS-dAdar and UAS-hADAR2 than in the Adar5G1rescues with the same UAS-ADAR transgenic lines (Table 3), presumably due to some assistance from the low level of residual dADAR in the Adar1F4 strain. Also RNA editing by ADAR1 is observed at more sites in ion channel transcripts in the Adar1F4 rescue but the pattern of sites with high and low levels of editing is very different from that seen in wild-type flies or in rescues by Drosophila ADAR protein or human ADAR2 (Table 3). This is exemplified by editing of the Nic 34E transcript where sites that are normally edited to 100% are edited slightly or not all by ADAR1 yet other sites within in the same transcript are highly edited by ADAR1p110 (Nic 34E I/M site, 84%) Editing activity is due to ADAR1 itself and not to endogenous Drosophila ADAR protein because no editing is observed at any site in transgenic flies expressing catalytically inactive ADAR1 EA (not shown). We conclude that human ADAR1, even when it succeeds in editing ion channel transcripts in Drosophila, does not restore the wild-type pattern of editing.

The ADAR proteins are expressed at low levels and cannot be detected on immunoblots of total protein extracts from embryos, whole flies or fly heads. In the case of ADAR2 low level expression in mammalian cells is due to the activity of a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase (R. Marcucci, manuscript in preparation). To express ADARs strongly in embryos male flies of UAS-ADAR lines were crossed to actin 5C-GAL4 / SM5 Cy and soluble protein extracts were made from 48-h embryo collections. The FLAG-tagged ADAR proteins were immunoprecipitated from extracts with anti-FLAG antibodies and the proteins were detected on immunoblots with anti-FLAG or anti-His antibodies. This allowed confirmation that proteins of the expected sizes are expressed at similar though not identical levels. The ADAR1p150 protein was not detected in this way but other evidence indicates that this protein is expressed and that it behaves differently than ADAR1p110 (36).

To ascertain if the fly and human proteins have similar levels of RNA editing activity in transgenic flies and therefore similar protein expression, we analysed non-specific RNA editing of the Rnp-4F transcript. This transcript is overlapped at the 3′-end by a convergently transcribed antisense transcript generated by read-through at the transcription terminator of the convergently transcribed gene (37). The resulting dsRNA is promiscuously edited by ADARs. Non-specific editing in the Rnp-4F transcript is rescued to the same level as in wild-type (approximately 14%) in Adar mutant flies rescued by expression of dADAR 3/4, ADAR1 p110 and p150 and human ADAR2 under engrailed-GAL4 control.

Locomotion defects in Adar mutant flies are rescued by expression of ADAR specifically in motor neurons

We have tested rescue of the locomotion defect by ADARs using a wide range of GAL4 drivers in addition to Cha-GAL4. We constructed a strain that had Adar5G1 on the X chromosome and a UAS-dAdar 3/4 S construct on the second chromosome and crossed a number of different GAL4 drivers to this strain (Figure 3). Surprisingly the enhancer trap GAL4 driver lines D42 and OK6 that drive GAL4 and UAS construct expression specifically in motor neurons, give efficient rescue of the Adar locomotion defect (Figure 3). In Drosophila neuromuscular junctions are primarily glutamatergic. The GAL4 enhancer trap line OK371 has a GAL4 insert in the promoter region of the gene encoding the vesicular glutamate transporter and this line directs expression in motor neurons as well as widely in a range of other glutamatergic neurons in the brain. None of the driver lines tested has expression that is absolutely restricted to motor neurons although OK6 has very little expression elsewhere in the CNS (31). Also the locomotion rescue by all three GAL4 driver lines is consistent with motor neurons being the main focus of the locomotion defect. Among all GAL4 drivers we have tested those whose expression patterns are known to include motor neurons consistently give efficient locomotion rescue.

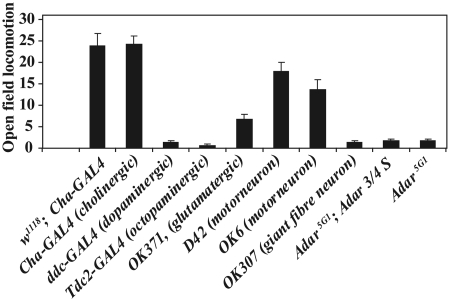

Figure 3.

Adar expression in cholinergic or motor neurons is sufficient to rescue Adar5G1 mutant locomotion defects. The chart shows open field locomotion in Adar5G1 flies, Adar5G1; UAS-Adar 3/4 S flies having this UAS construct in the absence of any GAL4 driver to induce expression or lines in which the UAS-Adar 3/4 S construct is expressed in the Adar5G1 background under the control of different GAL4 drivers. The wild-type control is w1118, Adar wild-type having a Cha-GAL4 driver to control for locomotion effects of widespread and strong GAL4 expression. Drivers expressing GAL4 in motor neurons, giant fibre escape neurons and different chemical classes of neurons are indicated. Drivers expressing GAL4 specifically in motor neurons (OK6, D42 and OK371) and Cha-GAL4 which expresses GAL4 in cholinergic neurons and some motor neurons direct efficient rescue.

Drivers expressing in neurons of other pharmacological types implicated in the central control of movement such as ddc-GAL4 (dopamine decarboxylase in dopaminergic neurons) or Tdc2-GAL4, (tyrosine decarboylase 2 in octopaminergic neurons) are not sufficient to direct locomotion rescue. Expression of ADARs in muscles, (How(Held-out wings)-GAL4) or in glia, (nrv(nervana)-GAL4) do not give rescue of walking defects (data not shown).

Human ADAR2 suppresses age-dependent neurodegeneration in Adar mutant Drosophila

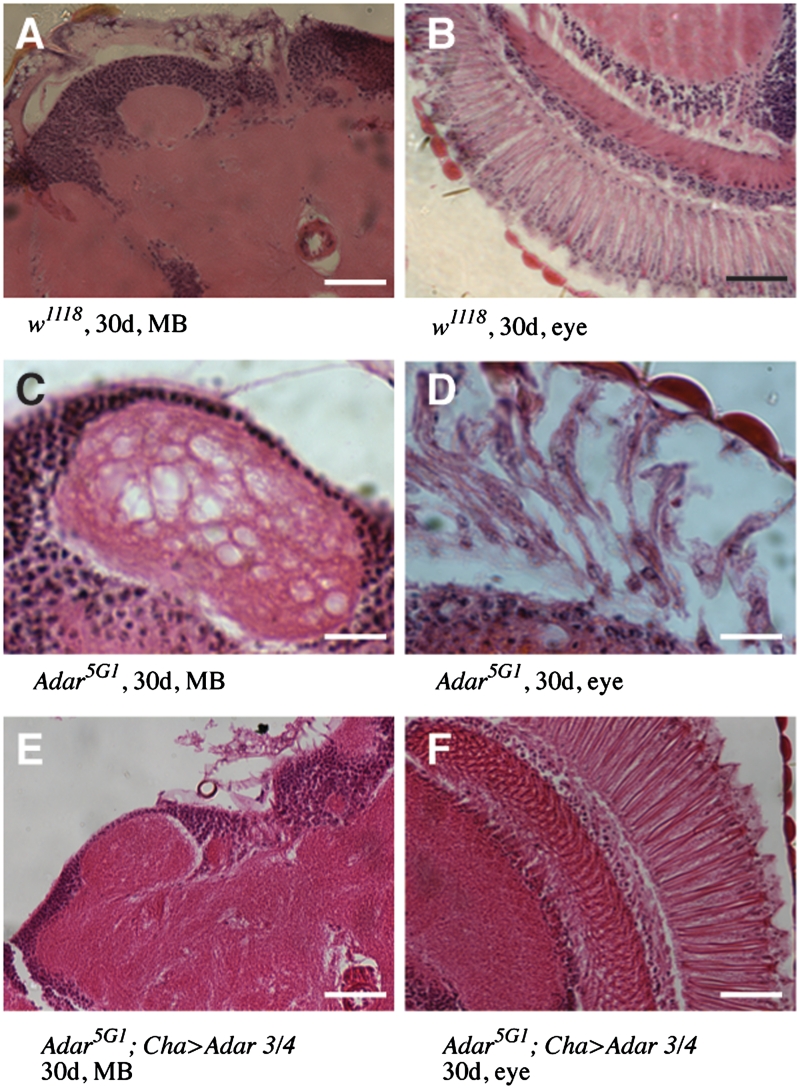

Adar1F4 flies undergo progressive vacuolization of the synaptic neuropile from 30 to 50 days (14). As the Adar5G1 deletion mutant is less viable than the Adar1F4 mutant strain it was hypothesized that the neurodegeneration in Adar5G1 would be more aggressive. To characterize the neurodegeneration pattern of the Adar5G1 mutant strain, Adar5G1 mutant males were aged, and heads were sectioned at 30 days and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (Figure 4). This revealed that vacuolization occurred in the Adar5G1 mutant as it did in the Adar1F4 mutant. However the neurodegeneration was more aggressive in the Adar5G1 mutant, not only affecting the retina (Figure 4D, compare to wild-type in B), but also the paired mushroom body (MB) calyces on the dorsal brain (Figure 4C, compare to wild-type in A). The mushroom body calyces are neuropil which is comprised of the dendrites of mushroom body Kenyon cells whose haematoxylin-stained nuclei lie above the calyces, and the axonal collaterals of projection neurons extending to them from the paired olfactory glomeruli on the ventral brain above the antennae.

Figure 4.

Suppression of neurodegeneration in Adar5G1 mutant flies by Drosophila ADAR. (A and B). Haematoxylin and eosin stained frontal sections of 30-day-old wild-type (w1118) heads show no neurodegeneration in the mushroom body calyces or in the eye. Scale bars: 20 µM. (C and D) Frontal sections of 30 day-old Adar5G1 heads show vacuolization and loss of Mushroom Body calyx neuropil (C) and large vacuoles in the retina of the eye (D) of Scale bars: 5 µM. (E and F) Frontal sections of 30-day-old Adar5G1; Cha GAL4, UAS-Adar 3/4 heads show rescue of vacuolization in the MB calyx and in the eye. Scale bars: 20 µM.

To confirm that the neurodegeneration that had been observed in aged Adar5G1 is due to the Adar deletion, the UAS-Adar 3/4 transgenic line was crossed into Adar5G1; Cha-GAL4. The Adar5G1mutant male rescued by expression of dAdar 3/4 in the cholinergic nervous system was aged to 30 days and the MB calyces and retina were analysed by haematoxylin and eosin staining of head sections. The vacuolization of the neuropil of the MB calyces and retina of the Adar5G1; Cha-GAL4 male rescued with Adar 3/4 is significantly reduced compared to the Adar5G1mutant strain at 30 days (Figure 4).

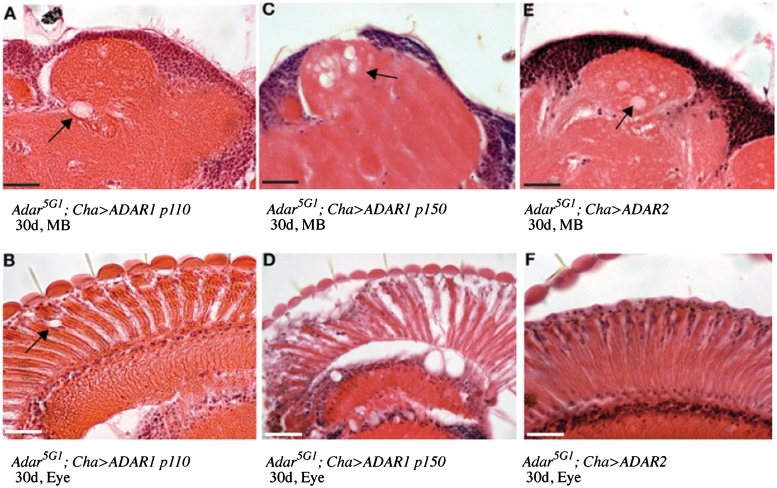

As neurodegeneration in the Adar5G1 mutant strain is successfully suppressed by Cha-GAL4-driven expression of dAdar, it was therefore possible to compare suppression of this phenotype by human ADARs. We aged the transgenic flies to 30 days to visualize neurodegeneration (Figure 5). Human ADAR2 suppresses neurodegeneration of both the calyces of the mushroom body (Figure 5E) and in the retina (Figure 5F) as effectively as Drosophila ADAR in the Adar5G1 mutant background in flies aged to thirty days. The suppression of neurodegeneration at thirty days is weaker with the nuclear p110 form of human ADAR1 (Figure 5A, ADAR1p110 calyx, Figure 5B, ADAR1p110 retina) but is lacking entirely with the cytoplasmically accumulating p150 isoform of ADAR1 (Figure 5C, ADAR1p150 calyx, Figure 5D, ADAR1p150 retina), suggesting that suppression of neurodegeneration is associated with nuclear localization of the ADAR proteins. It appears that suppression of neurodegeneration by ADAR proteins is easier to obtain than rescue of the locomotion defect.

Figure 5.

Suppression of neurodegeneration at 30 days in Adar5G1 mutant flies by human ADAR2. (A and B): Haematoxylin and eosin stained frontal sections of 30-day-old Adar5G1; Cha-GAL4, UAS-ADAR1p110 heads show rescue of neurodegeneration in the mushroom body (MB) calyces of the Adar5G1 mutant. (A). Some small vacuoles remain in the retina (B). Arrows indicate vacuolization. (C and D): Frontal sections of 30-day-old Adar5G1; Cha-GAL4, UAS-ADAR1p150 heads show lack of neurodegeneration rescue in the MB calyces of Adar5G1 (C) The retina degenerated rapidly (D). (E and F): Frontal sections of 30-day-old Adar5G1; Cha-GAL4, UAS-ADAR2 heads show rescue of vacuolization of the MB calyces (E) and the eye (F). Scale bars: 20 µM.

Insects have lost the ADAR1 gene

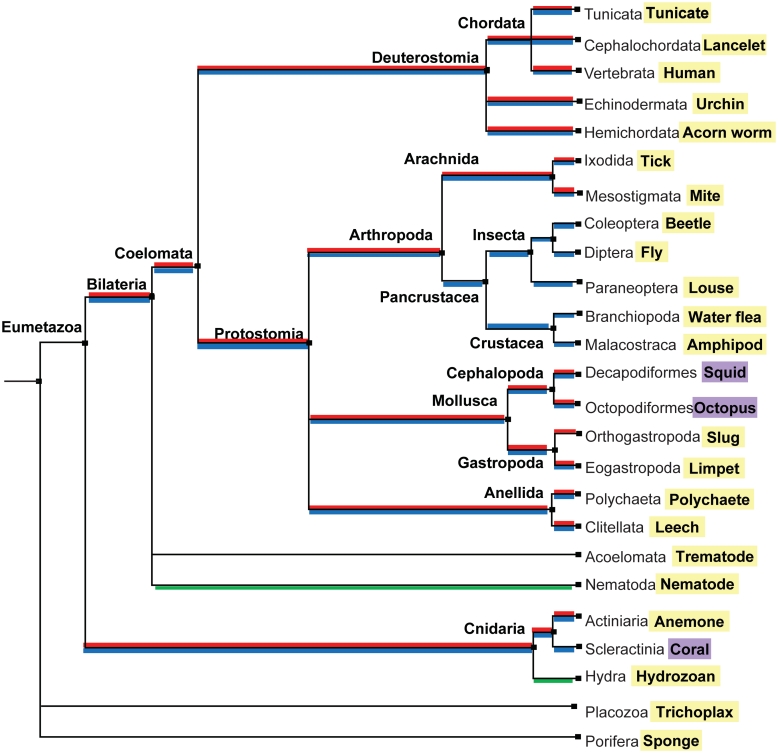

Human ADAR2 expressed in Drosophila matches the target site specificity of dADAR and rescues mutant phenotypes surprisingly well while human ADAR1 does not. These data suggest that Drosophila Adar may be a true orthologue of human ADAR2 rather than an invertebrate gene ancestral to both vertebrate ADARs. Because the Drosophila genome harbours a single Adar gene, this idea would imply that flies have lost an ADAR1 orthologue. Sequence data from recent invertebrate genome projects supports this idea. Many genes that were previously assumed to have first appeared only at the separation of Chordates from invertebrates have now been found in some of the simplest invertebrates like cnidarians (25). Both the ADAR1 and ADAR2 genes are in this category.

Figure 6 shows results of our searches for invertebrate ADARs mapped onto the phylogeny of all Metazoans that extend a previous report (38) (Supplementary Table S2). For all putative ADAR sequences, the deaminase domain was aligned with those from human ADAR1 and ADAR2. In most cases each ADAR could be classified as an orthologue of ADAR1 or ADAR2 with a high degree of confidence (Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). Surprisingly, having discrete ADAR1 and ADAR2 genes is an ancient characteristic, present throughout the Eumetazoa lineage, including its oldest phylum, the Cnidaria. In a few cases, however, ADAR1 appears to have been lost. For example, an ADAR1 orthologue was not found in multiple insect and crustacean genomes. It was found in some arachnids, indicating that it was not lost in all arthropods. Among the cnidarians, hydrozoans also seem to have lost ADAR1, although it was present in anemones (its presence or absence in corals cannot be clearly inferred because no genome is available, only a partial EST library). ADAR2 appears to be more ubiquitous. In fact, the only genome that possibly lacks an ADAR2 orthologue, but contains one for ADAR1, is Aplysia. However, the apparent absence of an Aplysia ADAR2 could be due to incomplete coverage of the Aplysia genome. Interestingly, nematodes and flatworms have neither a true ADAR1 nor ADAR2 orthologue. The two Adr genes from Caenorhabditis elegans cannot be classified into either group (39).

Figure 6.

Occurrence of ADAR1 and ADAR2 genes in the Metazoa. The phylogenetic tree of species was obtained from Taxonomy Common Tree NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/CommonTree/wwwcmt.cgi). Species names at the ends of branches highlighted in yellow represent available genomes that were searched for ADAR1 or ADAR2 orthologues. Species names highlighted in purple were cases where ADARs were identified by direct cloning (cephalopods) or searching EST resources (coral). Positive identification of ADAR1 or ADAR2 is coloured in red and blue, respectively. ADARs that cannot be classified as either ADAR1 or ADAR2 are coloured in green.

Together the findings of an ancient Metazoan ADAR2 conserved between fly and human, and loss of an ancient Metazoan ADAR1 in insects explain the results of the rescue tests with human ADARs in fly and account for the surprising similarity in target site preferences between human ADAR2 and Drosophila ADAR.

DISCUSSION

We find that the target specificity of an ADAR2-type protein is conserved from fly to human allowing effective rescue of in vivo RNA editing, locomotion and neurodegenerative phenotypes in flies by human ADAR2. Neither ADAR1p110 nor ADAR1p150 efficiently edit critical sites in Drosophila transcripts nor rescue the Adar mutant locomotion phenotype. This data was obtained before the recent increase in vertebrate genome sequences and is well explained by the identification of ancient Metazoan ADAR1 and ADAR2 genes in invertebrate genomes. Previously these ADAR genes had been identified only in Chordate genomes and not in Drosophila and other insects. We find that ADAR2 is conserved in Drosophila and that ADAR1 has been lost from insects and crustaceans but is present in Arachnid genomes. The data also show that the Drosophila Adar mutant represents a very useful genetic model for ADAR2 loss of function effects in human disease even though different transcripts are edited in vertebrates and flies. Restoration of ADAR activity in motor neurons, a fundamental neuron type present in even the simplest metazoans, is sufficient to rescue locomotion defects in Adar mutant flies.

The lack of RNA substrates from Drosophila with defined ECS elements made it impossible to analyse the activities of ADAR1 and ADAR2 at many Drosophila editing sites in vitro. We find that RNA structures at specific editing sites in Drosophila are often difficult to predict from the genome sequence. Although vertebrate editing sites show easily recognized pairings between edited exons and editing site complementary sequence (ECS) elements that exist as contiguous stretches of sequence in nearby introns, some fly sites may have shorter fragmented ECSs, as shown for the Drosophila synaptotagmin1 (Syt1) transcript (40). To analyse rescue at more editing sites we expressed the human ADAR proteins in Drosophila and measured editing by these proteins in Adar mutant flies. We focused on 26 edited positions in four transcripts that were either constitutively highly edited at all developmental stages or edited only or predominantly in adult flies. We have also analysed other edited positions in many other transcripts, though not in such depth, and the overall pattern of editing at these other positions with different ADARs did not vary from our core set. Our data showed that the set of edited sites in Drosophila match the specificity of an ADAR2 enzyme but not an ADAR1 enzyme to a surprising extent, i.e. the fly ADAR does not appear to represent an evolutionary precursor that might combine features of two descendant vertebrate ADARs. This is consistent with greater sequence conservation between Drosophila ADAR and vertebrate ADAR2.

Human ADAR2 expressed in Drosophila mirrors the function of the fly gene in many respects. We found that actin 5C-GAL4 and other drivers that direct ubiquitous, high level expression of ADAR2 in embryos and larvae or Mef 2-GAL4 that directs similarly premature high level expression in muscles and heart cause embryonic and larval lethality. We have previously observed similar lethality with the edited dAdar S isoform that is the most active Drosophila ADAR isoform (30). This is presumably due to some transcripts being edited inappropriately early in development. Expressing either an edited-equivalent Drosophila UAS-ADAR 3/4 G isoform or UAS-ADAR2 G do not cause this lethality. Human ADAR2 also rescues neurodegeneration in Adar mutant flies as does dADAR 3/4.

Human ADAR2 does not rescue locomotion defects in the Adar mutants as well as expected since in the best-rescuing UAS-ADAR2 line sites in Drosophila transcripts are edited more effectively than in the best-rescuing dADAR 3/4 line (Tables 2 and 3). We do not know why this is. Since ADAR2 is less active than dADAR 3/4 in editing the dAdar exon 7 site in vitro (Figure 1B) it might be expected that for ADAR2 to edit sites in vivo in Drosophila more efficiently than dADAR 3/4 would require a higher level of ADAR2 expression. We cannot rule out that ADAR2 is more highly expressed than dADAR 3/4 and has also some deleterious effect due to a higher expression level that interferes with locomotion rescue.

We do not understand why ADAR1p110 also rescues neurodegeneration but the finding suggests that rescue of neurodegeneration may not be dependent on rescue of site-specific RNA editing. ADAR proteins may have dosage-sensitive effects independent of their RNA editing specificities since ADAR1p110 is able to rescue neurodegeneration even though it does not edit correctly. The ability to rescue neurodegeneration correlates with predominant localization to the nucleus. It does not appear likely that rescued RNA editing of a subset of the Drosophila sites is the reason that ADAR1p110 rescues neurodegeneration, since ADAR1p150 edits most of the same sites to some extent, but we cannot rule out this possibility. Editing independent effects of ADARs expressed in motor neurons might also account for the small improvements in locomotion seen when ADAR1 isoforms or inactive dADAR 3/4 EA are expressed in Adar mutant flies and might also contribute to the toxicity of high level ADAR1 isoform expression.

Ironically, even though the target specificity of ADAR2-like proteins is well conserved and Drosophila has many edited transcripts, there is no evidence that any editing sites are conserved between Drosophila and vertebrates. There is no evidence for editing of transcripts encoding ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits in Drosophila even though this family of genes is conserved with vertebrates; vertebrate glutamate receptor editing appears to have first evolved in fish. None of the many editing sites in Drosophila transcripts can be related to known editing sites in vertebrate homologues and the one known case where a fly and vertebrate transcript are edited at the equivalent codon appears to have arisen by convergent evolution rather than by conservation of the underlying dsRNA target structure (41). This makes more impressive the finding that human ADAR2 has retained specificity and rescues the Drosophila Adar mutant.

As Drosophila has lost ADAR1, the possibility existed that certain sites would remain ADAR1-preferred sites since dADAR may have a higher specific activity or a slightly broader specificity than the vertebrate ADARs (Figure 1B and C). However this has not occurred and the tested editing sites in Drosophila are all preferentially edited by ADAR2. RNA editing sites at sites once edited by ADAR1 may have adjusted to conform better with the ADAR2-like target specificity after ADAR1 was lost in insects and crustaceans. Now that so many RNA editing events have been detected in Drosophila (4), evolutionary comparisons across invertebrates may be able to establish whether some RNA editing events are conserved since the insects diverged from crustaceans or arachnids or more distant groups and perhaps also determine which ADARs edited these sites in more primitive invertebrates. We cannot exclude the possibility that human ADAR1 edits some completely unknown sites in RNA duplexes in Drosophila transcripts that might represent relics of ancient ADAR1 editing events. This could provide one explanation for the reduced viability associated with highly expressing ADAR1 isoforms but we did not see any evidence for new human ADAR1 RNA editing events close to the Drosophila editing sites examined in rescue lines in vivo. ADAR1-type sites retained in Drosophila might not be edited by Drosophila ADAR and it would require a genome-wide search by RNA Sequencing in ADAR1-expressing flies to detect them, if they are still present. It is not clear however that ADAR1 editing sites would be conserved since the beginning of modern insects. Whole genome sequences are available for only a limited number of insect and crustacean species so there could be some insects and crustaceans that do still have ADAR1. With the full extent of editing in humans still to be determined, 4% of Drosophila transcripts affected and indications that RNA editing may be even more widespread in squid studies on the evolutionary origins of RNA editing sites and the selective forces maintaining them will expand our understanding of the role of RNA in gene expression.

What is most surprising is that ADAR1, an essential gene in mammals, has been lost in some invertebrates. Is there a biological role of ADAR1 other than site-specific editing that became dispensable?

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Medical Research Council (U.1275.01.005.00001.01 to M.A.O’C); National Science Foundation (IBN-0344070); National Institute of Health (1 R01 NS064259 to J.R.); Medical Research Council Capacity Building Area Research Studentship (to L.M.); Medical Research Council and Edinburgh University (to S.P.); Scottish Motor Neurone Disease Association (to X.L.). Funding for open access charge: Medical Research Council (U.1275.01.005.00001.01).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Paul Perry and Matthew Pearson for imaging, and Craig Nicols for figures. The authors thank the Broad Institute Genome Sequencing Platform and Genome Sequencing and Analysis Program, Federica Di Palma, and Kerstin Lindblad-Toh for making the data for Aplysia californica available. The authors also thank Leonid Moroz from the Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience of the University of Florida for providing access to the unpublished octopus EST library.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heale BSE, O'Connell MA. Biological roles of ADARs. In: Grosjean H, editor. DNA and RNA Modification Enzymes: Structure, Mechanism, Function and Evolution. Austin: Landes Bioscience; 2009. pp. 243–258. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishikura K. Functions and regulation of RNA editing by ADAR deaminases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;79:321–349. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060208-105251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stefl R, Oberstrass FC, Hood JL, Jourdan M, Zimmermann M, Skrisovska L, Maris C, Peng L, Hofr C, Emeson RB, et al. The solution structure of the ADAR2 dsRBM-RNA complex reveals a sequence-specific readout of the minor groove. Cell. 2010;143:225–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graveley BR, Brooks AN, Carlson JW, Duff MO, Landolin JM, Yang L, Artieri CG, van Baren MJ, Boley N, Booth BW, et al. The developmental transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2011;471:473–479. doi: 10.1038/nature09715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoopengardner B, Bhalla T, Staber C, Reenan R. Nervous system targets of RNA editing identified by comparative genomics. Science. 2003;301:832–836. doi: 10.1126/science.1086763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stapleton M, Carlson JW, Celniker SE. RNA editing in Drosophila melanogaster: new targets and functional consequences. RNA. 2006;12:1922–1932. doi: 10.1261/rna.254306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palavicini JP, O'Connell MA, Rosenthal JJ. An extra double-stranded RNA binding domain confers high activity to a squid RNA editing enzyme. RNA. 2009;15:1208–1218. doi: 10.1261/rna.1471209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patton DE, Silva T, Bezanilla F. RNA editing generates a diverse array of transcripts encoding squid Kv2 K+ channels with altered functional properties. Neuron. 1997;19:711–722. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenthal JJ, Bezanilla F. Extensive editing of mRNAs for the squid delayed rectifier K(+) channel regulates subunit tetramerization. Neuron. 2002;34:743–757. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colina C, Palavicini JP, Srikumar D, Holmgren M, Rosenthal JJ. Regulation of Na+/K+ ATPase transport velocity by RNA editing. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higuchi M, Maas S, Single FN, Hartner J, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Feldmeyer D, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH. Point mutation in an AMPA receptor gene rescues lethality in mice deficient in the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR2. Nature. 2000;406:78–81. doi: 10.1038/35017558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li JB, Levanon EY, Yoon JK, Aach J, Xie B, Leproust E, Zhang K, Gao Y, Church GM. Genome-wide identification of human RNA editing sites by parallel DNA capturing and sequencing. Science. 2009;324:1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1170995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palladino MJ, Keegan LP, O'Connell MA, Reenan RA. dADAR, a Drosophila double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase is highly developmentally regulated and is itself a target for RNA editing. RNA. 2000;6:1004–1018. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palladino MJ, Keegan LP, O'Connell MA, Reenan RA. A-to-I pre-mRNA editing in Drosophila is primarily involved in adult nervous system function and integrity. Cell. 2000;102:437–449. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greger IH, Khatri L, Ziff EB. RNA editing at arg607 controls AMPA receptor exit from the endoplasmic reticulum. Neuron. 2002;34:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00693-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greger IH, Khatri L, Kong X, Ziff EB. AMPA receptor tetramerization is mediated by q/r editing. Neuron. 2003;40:763–774. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00668-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawahara Y, Ito K, Sun H, Aizawa H, Kanazawa I, Kwak S. Glutamate receptors: RNA editing and death of motor neurons. Nature. 2004;427:801. doi: 10.1038/427801a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng PL, Zhong X, Tu W, Soundarapandian MM, Molner P, Zhu D, Lau L, Liu S, Liu F, Lu Y. ADAR2-dependent RNA editing of AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 determines vulnerability of neurons in forebrain ischemia. Neuron. 2006;49:719–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartner JC, Schmittwolf C, Kispert A, Muller AM, Higuchi M, Seeburg PH. Liver disintegration in the mouse embryo caused by deficiency in the RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:4894–4902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, Miyakoda M, Yang W, Khillan J, Stachura DL, Weiss MJ, Nishikura K. Stress-induced apoptosis associated with null mutation of ADAR1 RNA editing deaminase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:4952–4961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartner JC, Walkley CR, Lu J, Orkin SH. ADAR1 is essential for the maintenance of hematopoiesis and suppression of interferon signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:109–115. doi: 10.1038/ni.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steitz TA. Similarities and differences between RNA and DNA recognition by proteins. In: Gesteland RF, Atkins JF, editors. The RNA World. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 219–237. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehmann KA, Bass BL. Double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminases ADAR1 and ADAR2 have overlapping specificities. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12875–12884. doi: 10.1021/bi001383g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scadden AD, O'Connell MA. Cleavage of dsRNAs hyper-edited by ADARs occurs at preferred editing sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5954–5964. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Putnam NH, Srivastava M, Hellsten U, Dirks B, Chapman J, Salamov A, Terry A, Shapiro H, Lindquist E, Kapitonov VV, et al. Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organization. Science. 2007;317:86–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1139158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ring GM, O'Connell MA, Keegan LP. Purification and assay of recombinant ADAR proteins expressed in the yeast Pichia pastoris or in Escherichia coli. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;265:219–238. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-775-0:219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Connell MA, Gerber A, Keller W. Purification of human double-stranded RNA-specific editase 1 (hRED1) involved in editing of brain glutamate receptor B pre-mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:473–478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito K, Awano W, Suzuki K, Hiromi Y, Yamamoto D. The Drosophila mushroom body is a quadruple structure of clonal units each of which contains a virtually identical set of neurones and glial cells. Development. 1997;124:761–771. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.4.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salvaterra PM, Kitamoto T. Drosophila cholinergic neurons and processes visualized with Gal4/UAS-GFP. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2001;1:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(01)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keegan LP, Brindle J, Gallo A, Leroy A, Reenan RA, O'Connell MA. Tuning of RNA editing by ADAR is required in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2005;24:2183–2193. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanyal S. Genomic mapping and expression patterns of C380, OK6 and D42 enhancer trap lines in the larval nervous system of Drosophila. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2009;9:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahr A, Aberle H. The expression pattern of the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter: a marker protein for motoneurons and glutamatergic centers in the brain. Gene Expr. Patterns. 2006;6:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melcher T, Maas S, Herb A, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, Higuchi M. A mammalian RNA editing enzyme. Nature. 1996;379:460–464. doi: 10.1038/379460a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desterro JM, Keegan LP, Lafarga M, Berciano MT, O'Connell M, Carmo-Fonseca M. Dynamic association of RNA-editing enzymes with the nucleolus. J. Cell. Sci. 2003;116:1805–1818. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sommer B, Kohler M, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH. RNA editing in brain controls a determinant of ion flow in glutamate-gated channels. Cell. 1991;67:11–19. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90568-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heale BS, Keegan LP, McGurk L, Michlewski G, Brindle J, Stanton CM, Caceres JF, O'Connell MA. Editing independent effects of ADARs on the miRNA/siRNA pathways. EMBO J. 2009;28:3145–3156. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peters NT, Rohrbach JA, Zalewski BA, Byrkett CM, Vaughn JC. RNA editing and regulation of Drosophila 4f-rnp expression by sas-10 antisense readthrough mRNA transcripts. RNA. 2003;9:698–710. doi: 10.1261/rna.2120703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin Y, Zhang W, Li Q. Origins and evolution of ADAR-mediated RNA editing. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:572–578. doi: 10.1002/iub.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonkin LA, Saccomanno L, Morse DP, Brodigan T, Krause M, Bass BL. RNA editing by ADARs is important for normal behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 2002;21:6025–6035. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reenan RA. Molecular determinants and guided evolution of species-specific RNA editing. Nature. 2005;434:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature03364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhalla T, Rosenthal JJ, Holmgren M, Reenan R. Control of human potassium channel inactivation by editing of a small mRNA hairpin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:950–956. doi: 10.1038/nsmb825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.