Abstract

This review explores research on public perceptions of nanotechnology. It highlights a recurring emphasis on some researchers’ expectations that there will be a meaningful relationship between awareness of nanotechnology and positive views about nanotechnology. The review, however, also notes that this emphasis is tacitly and explicitly rejected by a range of multivariate studies that emphasize the key roles of non-awareness variables, such as, trust, general views about science, and overall worldview. The review concludes with a discussion of likely future research directions, including the expectation that social scientists will continue to focus on nanotechnology as a unique opportunity to study how individuals assess risk in the context of relatively low levels of knowledge.

Introduction

As this review shows, a number of scholars in social science disciplines, such as political science and science communication, have turned their attention to exploring how individuals perceive nanotechnology's risks and benefits. Research in this area continues to provide a unique opportunity to track risk perceptions, whereas nanotechnology discussions are just beginning to appear in the public sphere. Many of those involved in this research, and cited below, had previously studied emerging technology areas, such as nuclear energy and agricultural biotechnology, and saw the opportunity to help decision makers avoid some of the communication missteps that proponents of previous technologies had committed. Technology advocates often point to these communication failures as the cause of unwarranted public health and environmental concerns.1 At the academic level, the emergence of nanotechnology as a potential subject of social research also corresponded with more general discussions within academia and government in both Europe and North America about the value of ‘upstream’ public involvement in science decision making.2–4

The current review describes research on nanotechnology perceptions, with an emphasis on both studies focused on basic nanotechnology awareness as well as more theoretically guided work that focuses on understanding the dynamics underlying nanotechnology attitude formation and expression. In doing so, it seeks to identify challenges in the literature, particularly areas where scholars have failed to adequately draw on previous literature in developing their research. It finishes with a brief discussion of the likely future direction of work in this area. The articles noted were found based on initial Web of Science searches for: ‘nano*’ AND (‘opinion*’ OR ‘survey*’ OR ‘experiment*’). The cited references for these articles were then examined for additional relevant studies. The search also highlighted several media content analyses, which are also summarized briefly below to provide context for the opinion-oriented research. As a review of public perceptions, only studies where an attempt was made to obtain a representative sample of a population (or sub-population) are included. Although many of the studies use random digit dialing, several use mail or online surveys. This excludes, for example, experimental studies using non-probability samples5, 6 or volunteer surveys.7 It also excludes qualitative studies that explore how individuals shape their views about nanotechnology and associated actors through discussion, although these generally support the results described below.8–10 Because this review represents secondary research, no institutional review board approval was sought for this review.

Nanotechnology involves ‘the understanding and control of matter at the dimensions of roughly 1–100nm where unique phenomena enable novel applications’.11 This definition emphasizes that nanotechnology is not a specific product but is, rather, a scale at which scientists or companies may manipulate or produce objects. The ability to work at this level opens up opportunities for advances in key economic fields, such as electronics, materials and pharmaceuticals, as well as a range of consumer product areas such as cosmetics. As of mid 2010, the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies (PEN), a project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the Pew Charitable Trusts, had identified more than 1000 consumer products that manufacturers have specifically said to make use of nanotechnology, with more applications becoming commercially available every month.12 Although one study has questioned the validity of the PEN database,13 it is clear that many nanotechnology products are currently on the market.

Government agencies responsible for science and economic development in many countries have identified nanotechnology as a key area of strategic importance and have devoted substantial resources toward basic and applied research.14–16 Several social science-based projects have also received funding. The PEN initiative has funded a number of surveys, and many of the studies described below are the result of a large National Science Foundation (NSF) initiative to create the Center for Nanotechnology in Society at Arizona State University17–23 and the Center for Nanotechnology in Society at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The NSF has also provided funding to social scientists at other universities, including the University of South Carolina,8, 23, 24 Cornell University,25, 26 North Carolina State University,6, 27, 28 Yale University29 and Rice University.30 Even studies focused on Britain and Europe report receiving some NSF support.9, 31 Funding has also been provided for humanities-oriented work in areas such as philosophy and history but these areas will not be discussed here. Nevertheless, critics have often argued that funders are devoting too little funding to assess the potential health, environmental and social consequences of nanotechnology.32, 33 This tension between economic, social and ethical concerns has been captured in recent research on media coverage of nanotechnology.

Media content finding: focus on progress

In addition to the survey research described below, a number of systematic assessments of media content have also focused on nanotechnology, starting with a handful of studies in 2005. Building on similar work about previous emerging technologies,34–36 the nanotechnology content analyses show that most coverage tends to focus on technological process and, only rarely, health and environmental risks or ethical concerns. Health and risk content appears to have become more common over time but, overall, coverage of any aspect of nanotechnology has continued to remain relatively rare.23, 37–41 These initial content analyses looked at the United States23,37, 38 and the United Kingdom.23, 38–40 More recent studies have looked in more detail at subissues such as nanoparticle safety,40 the emergence of more increased regulatory focus,41 economic coverage of nanotechnology, as well as coverage in smaller countries such as Denmark.42 Some recent studies have also relied on interviews with journalists who cover nanotechnology to emphasize the challenges of communicating uncertain science appropriately.43, 44 Given the relative paucity of coverage, however, there is no evidence that the news media are driving the debate about nanotechnology.

Survey research finding: low knowledge

It is consistent with the low levels of media coverage and it should perhaps come as little surprise that the earliest and most consistent finding of nanotechnology survey research is that the public does not know much about nanotechnology. For example, one attempt by Satterfield et al.45 to synthesize the survey work up to 2008 shows that about half of respondents in the reported studies said they had no familiarity with nanotechnology. Annual telephone surveys conducted for the Woodrow Wilson center starting in 2006, some of which were included in the summary study, report that in 2006 and 2007, 42% of respondents (n = ~ 1000 in all years) said they had heard nothing about nanotechnology. This number rose to 49% in the 2008 survey and then backed down to 37% in 2009. At the same time, the number of people who said they heard ‘a lot’ about nanotechnology hovered between 24 and 31% (ref. 46, see also online Supplementary material in ref. 47). Similar results from face-to- face surveys in the United Kingdom48 and telephone surveys in Canada49 and Japan50 were included in the summary study. An additional convenience sample study of (primarily) young people26 and more recent online studies from Germany51 and France52 also found similar results in those countries. A broader European study, although not specifically asking about nanotechnology awareness, found that 53% of Europeans sampled in a 2004 survey said that they did not know enough to answer a question about whether nanotechnology ‘will improve (their) way of life in the next 20 years (29%)’ or whether it would have no effect (12%) or whether it will make things worse (6%).31

One noteworthy aspect of the research underlying the consensus that the public know little about nanotechnology is that most of the data focus on respondents’ self-reported level of awareness. Few studies include tests specifically meant to assess knowledge (that is, true/false tests). When administered, these tests indicate that, on balance, respondents generally understand that nanotechnology is an economic issue, is invisible to the naked eye and involves the modification of materials.18, 20, 28

Survey research finding: benefits outweigh the risks

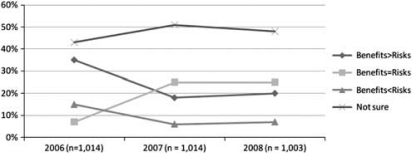

Beyond reports of low knowledge levels, the second most common survey feature is the finding that when people have an opinion (and an average of about half of those surveyed did not), they see more promise than peril in nanotechnology. 46 Most of this research (for example, refs 28, 29, 31, 48, 49, 51–53) involves asking survey participants directly whether they think nanotechnology will be, on balance, good or bad. For example, the Peter D Hart Associates research for the Woodrow Wilson46 center asks respondents to indicate whether ‘benefits will outweigh the risks,’ ‘benefits will about equal the risks,’ ‘risk will outweigh the benefits’ or whether the respondent is ‘not sure’ (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Initial impression of nanotechnology benefits versus risks from the Project on Emerging Nanotechnology as adapted from surveys collected by Peter D Hart Associates.62, 79

In contrast, telephone surveys by Scheufele and colleagues 17, 18, 20–22 as well as mail surveys by Siegrist and his colleagues54,55 ask multiple questions about specific potential risks of nanotechnology, followed by multiple questions about the potential benefits of nanotechnology. The goal in doing so was to ensure that the survey assessed the range of potential risks and benefits. One mail survey-based study used a hybrid approach asking for a direct weighting of relative risks and benefits, as well as questions specifically about perceived health and environmental risks.25 Although the different approaches to measurement still point to more positive than negative attitudes about nanotechnology, risks and benefits may also interact to amplify or attenuate the impact of such perceptions on willingness to accept nanotechnology.30

Survey research: relationship between awareness and attitude

Beyond simply describing nanotechnology awareness and perceived risks and benefits, most academic studies of nanotechnology opinion attempt to test the degree to which specific factors are driving opinion. As might be expected, the most common relationship assessed is the one between awareness and perceived risks and benefits. This focus on the relationship between knowledge and attitudes toward science has been the subject of substantial research for many years. Although scientists often appear to believe that, if people just knew more, they would have more positive attitudes toward its products,56, 57 academic research on this topic tends to show that that knowledge has relatively limited impact on attitudes toward emerging technologies. 58, 59 Science communication scholars have come to use the term ‘deficit model’ as a term-of-art in critiques of actors—usually scientists—who expect that increased scientific knowledge will inevitably lead to increased public acceptance of science.60, 61

The difficulty with critiquing the argument that knowledge is associated with attitudes is that the relationship sometimes exists.58 Indeed, a meta-analysis by Satterfield et al.45Fwhich focuses on similar themes to those described here but with a greater focus on the meta-analysis, less emphasis on critical review of findings from multivariate models, less emphasis on measurement and includes several different studies—confirms that that the available nanotechnology data suggest that increased self-reported awareness is associated with marginally more positive views. Online surveys from Germany51 and France,52 which were not included in Satterfield further, appear to suggest that awareness is associated with more positive views about nanotechnology after demographic controls and several additional explanatory variables (see Table 1). However, the studies that use the more elaborate test-based measures of knowledge (rather than self-reported awareness) find that basic science literacy rather than nanotechnology specific literacy is the more important predictor of positive views about nanotechnology,18, 20–22 although it is impossible to compare these studies directly because the latter studies focus on dependent variables, such as support for nanotechnology policies, rather than risks and benefits. One mail survey-based study that uses both an awareness self-report and a short, general science literacy quiz finds that although awareness is associated with lower risk perceptions, general science knowledge is not. This study, however, uses only a limited regional sample.25

Table 1.

Key variables in multivariate analyses of public opinion data about nanotechnology

| Study | Survey year | Risk/ benefits | Self-report aware | Knowl. (general/nano) | Trust | Religion | View of science/ science media use | Enviro values | Survey mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobb and Macoubrie27 | 2004 | Sig. | NS | Sig. | Sig. (view of sci) | Tel. | |||

| Lee et al.18a,* | 2004 | DV | NS | Sig. | Sig. (both) | Tel. | |||

| Gaskell et al.31 | 2004 | DV | Sig. | Sig. (view of sci.) | Sig. | Face | |||

| Scheufele and Lewenstein20a,* | 2004 | Sig. | NS | Sig. (sci. media) | Tel. | ||||

| Brossard et al.17a,* | 2004 | Sig. | NS (nano) | Sig. | Sig. (sci. media) | Tel. | |||

| Siegrist et al.55b | Not report | DV | Sig. | Sig. (view of sci.) | |||||

| Cook and Fairweather67c | 2006 | Sig. | Sig. | ||||||

| McComas et al.25d | 2006 | DV | Sig. | NS (general | NSd | Sig. | NS (sci. media) | ||

| Kahan et al.29 | 2006 | DV | Sig. | Online | |||||

| Stamfli et al.54b | 2006 | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. (view of sci.) | |||||

| Scheufele et al.47**,e | 2007 | Sig. (nano) | NSd | Sig. | Tel. | ||||

| Cacciatore et al. (online first)22**,a | 2007 | Sig. | Sig. (nano) | NS | NS (sci. newspaper, sci. web), | Tel. | |||

| . | . | Sig. (sci. TV) | |||||||

| Ho et al.21**,a | 2007 | Sig. | NS (nano) | Sig. | Sig | Sig. (both) | Tel. | ||

| Vandermoere et al. (online first)52f | 2008 | Sig. | Sig | Sig. (view of sci.). | Sig | Online | |||

| Vandermoere et al51 | 2008 | DV | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. (view of sci.). | Sig | Online |

Abbreviations: DV, dependent variable in study, Sig.; variable was significant in final model; NS, variable was not significant in final model.

DV=for support for nanotechnology funding.

DV=willingness to buy nanotechnology related food product.

DV=willingness to buy nanotechnology beef or lamb.

Interpersonal fairness.

DV=moral acceptability.

DV=support for nanotechnology food packaging.

Used the same survey data. Tel.=telephone.

Survey research: experimental studies

Several survey studies have embedded a knowledge-building or issue-framing experiment into the design of the survey itself. For example, an early phone survey-based experiment gave respondents a description of nanotechnology framed in one of 10 different ways (for example, focus on health benefits, focus on health risks and so on) and found that nanotechnology explanations that focused only on risks or only on benefits change the balance of perceived risks and benefits.27 Smiley Smith et al.53 analyzed a more straightforward pre-post survey-based experiment built into the 2006 Project for Emerging Nanotechnologies data in the United States62 and found that, when given a few paragraphs of basic information, some types of respondents (that is, men, those with more than a high school education and Republicans) were more likely to switch from saying that they did not know how they felt about nanotechnology to saying they believed that the benefits outweighed the risks. Other work, however, directly challenges this perspective by showing that increased information likely works by increasing the degree to which respondents draw on their preexisting cultural frameworks rather than the new information itself.29 On a different question, Siegrist63 embedded questions about food into one of their mail surveys and found that using nanotechnology to give food health benefits made the food less attractive than unmodified food.

Survey research: other explanatory variables

Trust has emerged as a standard variable in the risk communication literature64 and it has therefore been an important element of nanotechnology research as well. Some of the first published random sample-based surveys on nanotechnology emphasized that trust in business leaders28 and trust in scientists18,21 represent important predictors of views about nanotechnology. A later study similarly focused on general social trust,55 whereas others pointed to confidence in federal regulators and business leaders53 or a composite measure of business and scientific authorities.31 At a measurement level, the most comprehensive examination of trust and nanotechnology can be found in recent research by Siegrist54, aimed at understanding the willingness to buy nanotechnology-related foods. This study used a mail survey with a relatively small sample and found that trust in scientists and government regulators, as well as trust in private sector food actors, are associated with perceived benefits of nanotechnology food. Trust in private sector actors is also associated with lower perceived risk.54 Another mail survey-based study looked at the related concept of fairness, including the degree to which respondents felt scientists were interpersonally respectful and polite, but did not find relationships between this variable and views about nanotechnology.25

Several research projects have also explored religion as an explanation for nanotechnology views. This work is partially premised on work related to emerging medical technologies such as those associated with stem cell research.65 Such research emphasizes that religion provides one of several key predispositions or orientations that underlie attitudes about technologies.66 Although the German survey analysis reports little evidence that religiosity affects views about nanotechnology, 51 one US study showed that religiosity is associated with overall lower support for nanotechnology funding; it also appeared to interact with knowledge to keep nanotechnology support down among religious individuals who also have relatively high levels of knowledge17 (see also refs 21, 22). Religious importance has also been used as a basic control variable and found to be significant predictor of support for science authority25 and food perceptions.67

The other main predictors of nanotechnology explored in the literature are overall attitudes toward science and views about the environment. As might be expected, given low levels of specific knowledge about nanotechnology, the general ‘attitude toward science’ variable has proven to be one of the most consistently significant predictors of views about nanotechnology.18, 21, 28, 31, 51, 52 Science media use, inasmuch as it also represents an underlying interest in science, has similarly been found to have a significant role in some studies.17, 18, 20, 47 The positive relationship between general support for, or interest in, science is contrasted by a negative relationship between environmental values and positive views about nanotechnology.31, 51, 52

A mail survey study from New Zealand that looked at self reported intention to purchase lamb or beef that had been genetically modified using nanotechnology67 found that a number of variables associated with Theory of Planned Behavior, including self-identity, attitude toward such modifications and perceived norms,68, 69 were significant predictors of potential buying intentions.67 The study did not, however, include any of the other standard variables, such as trust, knowledge or views about the religion or the environment.

Table 1 summarizes the multivariate studies that have looked at views about nanotechnology.

Demographics have not generally been a key element of discussion about nanotechnology perceptions but some specific variables are consistently significant predictors of views about risk.70 In the studies reviewed here, men,18, 20, 25, 31, 51, 53, 55, 68 older respondents,31, 53 Whites,28, 47 those with relatively higher levels of education,18, 28, 31, 47, 53, 67 those with relatively higher levels of income18,53, 67 and conservatives31,25 sometimes appear to be more positive about nanotechnology in the available multivariate analyses.

Survey research: experts' views

A small number of studies have explored what nanotechnology scientists think about the risks and benefits of nanotechnology. Two of the surveys drew on an attempted census of US main authors who published on nanotechnology in ISI-referenced journals,19, 71, 23 whereas the third attempted a census of scientists at a specific European conference.55 Two of these articles included comparison data from public opinion surveys.19, 55 The two US-focused surveys, one of which resulted in two separate studies,23, 71 find that scientists see a range of benefits for nanotechnology, particularly in the areas of health and the environment, but that they are also concerned about health and environmental impacts,23 perhaps even more so than the public.19 The European study suggested that the public makes risk judgments based on a combination of social trust, perceived risk benefits and overall views about technology, whereas only social trust matters have a part in scientists’ risk judgments.55

Conclusions and next steps

Given the number of researchers currently engaged in the field, as well as the fact that these respondents come from a range of disciplines, the social scientific literature related to nanotechnology perceptions is likely to continue to expand for the foreseeable future. Few social scientists associated with nanotechnology research would likely admit to hoping that public opinion about the subject follows the trajectory of previous emerging technologies such as agricultural biotechnology or nuclear energy and becomes an object of social division. Nevertheless, the survey work described can provide the field baseline findings against which to compare any future changes in the public perceptions, should nanotechnology emerge as a contentious public issue. Even if few questions about nanotechnology surface, the study of nanotechnology has provided a unique opportunity to test the key role that variables such as trust, cultural worldviews and religion have in shaping views about technology. Further, showing that scientific knowledge is rarely a key predictor of attitudes about nanotechnology gives social scientists the opportunity to demonstrate their expertise to research scientists and professionals more directly involved in scientific research.

Rather than focusing on simply educating members of the public, for example, Nisbet and Scheufele72 have argued that scientists need to work with communication experts to frame emerging science in ways that resonate with citizens’ existing worldviews. This perspective has also contributed to discussions about how to best address skepticism over climate change.73 Kahan, whose work points in a similar direction,29, 66 has recently explored the usefulness of this approach in the context of the emerging area of synthetic biology in working papers.74, 75 Nisbet and Scheufele72 and others25 have also argued that the primacy of variables such as trust suggests the need for scientists to devote substantial resources to honest and respectful engagement with the public.

Even if no public debate emerges, additional research may also benefit from focusing on specific rather than general aspects of nanotechnology. In the area of biotechnology, for example, it became apparent over time that the public had different views about biotechnology in animals compared with plants.76 The expert surveys described above,19, 23 the experimental work by Cobb27 and some of the qualitative work not reviewed here9, 10 explored questions about specific nanotechnology applications. However, the work by Siegrist and his colleagues54 on food issues is the most specific work in this area. Performing valid research in the context of probability surveys, however, remains difficult given the low levels of general knowledge. Another potentially promising path to better understand public opinion about nanotechnology is to design studies that enable direct comparisons of views about nanotechnology and other technologies, an approach that has been part of only a few of the studies described above.25, 30

Survey mode, although addressed here in passing, may have a role in survey quality. Whereas online and mail surveys, if done appropriately, can often enable more detailed measurement at lower cost,77 they can also suffer from low response rates, and substantial efforts are required to demonstrate that the included sample adequately represents the target population.78 Whereas the Kahan nanotechnology data29 appears to satisfy this requirement, the French and German online panels appear to have used a less rigorous sampling methodology. Future research might explore whether survey mode has an impact on perceptions of emerging technology.

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the NSF Grants no. 0708466 and 0531160. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

References

- 1.Einsiedel EF, Goldenberg L. Dwarfing the social? Nanotechnology lessons from the biotechnology front. In: Hunt G, Mehta M, editors. Nanotechnology: Risk, Ethics, and Law. London, UK: Earthscan; 2006. pp. 213–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Research Council. Understanding risk: informing decisions in a democratic society. In: Stern PC, Fineberg HV, editors. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joss S, Belluci S, editors. Participatory Technology Assessment: European Perspectives. Gateshead. UK: Athenaeum Press/Centre for the Study of Democracy; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Einsiedel EF, Jelsoe E, Breck T. Publics at the technology table: the consensus conference in Denmark, Canada, and Australia. Public Underst Sci. 2001;10:83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schutz H, Wiedemann PM. Framing effects on risk perception of nanotechnology. Public Underst Sci. 2008;17:369–79. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macoubrie J. Nanotechnology: public concerns, reasoning and trust in government. Public Underst Sci. 2006;15:221–41. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bainbridge WS. Public attitudes toward nanotechnology. J Nanopart Res. 2002;4:561–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Besley JC, Kramer VL, Yao Q, Toumey CP. Interpersonal discussion following citizen engagement on emerging technology. Sci Commun. 2008;30:209–35. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pidgeon N, Harthorn BH, Bryant K, Rogers-Hayden T. Deliberating the risks of nanotechnologies for energy and health applications in the United States and United Kingdom. Nat Nano. 2009;4:95–8. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Priest S, Greenhalgh T, Kramer V. Risk perceptions starting to shift? US citizens are forming opinions about nanotechnology. J Nanopart Res. 2010;12:11–20. doi: 10.1007/s11051-009-9789-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Nanotechnology Initiative. Nanotech Facts. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation; 2010. (updated 2010; cited 4 May 2010). Available from: http://www.nano.gov/html/facts/home_facts.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies. Consumer Products: An Inventory of Nanotechnology-based Products Currently on the Market. Washington, DC: The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; 2010. (updated 2010; cited 2 May 2010). Available from: http://www.nanotechproject.org/inventories/consumer/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berube DM, Searson EM, Morton TS, Cummings CL. Project on emerging nanotechnologies: consumer product inventory evaluated. Nano Law Bus. 2010;7:152–63. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Nanotechnology Initiative. History. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation; 2010. (updated 2010; cited 2 May 2010). Available from: http://www.nano.gov/html/about/history.html. [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Commission. Nanotechnology. 2009. (updated 2009; cited 3 May 2010). Available from: http://cordis.europa.eu/nanotechnology/

- 16.Hebert P. Top Nations in Nanotech See Their Lead Erode. New York, NY: Lux Research Inc.; 2007. (updated 2007; cited 25 April 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brossard D, Scheufele DA, Kim E, Lewenstein BV. Religiosity as a perceptual filter: examining processes of opinion formation about nanotechnology. Public Underst Sci. 2009;18:546–58. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CJ, Scheufele DA, Lewenstein BV. Public attitudes toward emerging technologies: examining the interactive effects of cognitions and affect on public attitudes toward nanotechnology. Sci Commun. 2005;27:240–67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheufele DA, Corley EA, Dunwoody S, Shih TJ, Hillback E, Guston DH. Scientists worry about some risks more than the public. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:732–4. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheufele DA, Lewenstein BV. The public and nanotechology: how citizens make sense of emerging technologies. J Nanopart Res. 2005;7:659–67. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho S, Scheufele DA, Corley EA. Making sense of policy choices: understanding the roles of value predispositions, mass media, and cognitive processing in public attitudes toward nanotechnology. J Nanopart Res. 2010;12:2703–15. doi: 10.1007/s11051-010-0038-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cacciatore MA, Scheufele DA, Corley EA. From enabling technology to applications: the evolution of risk perceptionsm about nanotechnology. Public Underst Sci. 2009 (online first) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stephens LF. News narratives about nano S&T in major US and non-US newspapers. Sci Commun. 2005;27:175–99. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Besley JC, Kramer V, Priest SH. Expert opinion on nanotechno logy: risk, benefits, and regulation. J Nanopart Res. 2008;10:549–58. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McComas KA, Besley JC, Yang Z. Risky business: the perceived justice of local scientists and community support for their research. Risk Anal. 2008;28:1539–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldron A, Spencer D, Batt C. The current state of public understanding of nanotechnology. J Nanopart Res. 2006;8:569–75. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cobb MD. Framing effects on public opinion about nanotechnology. Sci Commun. 2005;27:221–39. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cobb MD, Macoubrie J. Public perceptions about nanotechnology: risks, benefits, and trust. J Nanopart Res. 2004;6:395–405. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahan DM, Braman D, Slovic P, Gastil J, Cohen G. Cultural cognition of the risks and benefits of nanotechnology. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Currall SC, King EB, Lane N, Madera J, Turner S. What drives public acceptance of nanotechnology? Nat Nanotechnol. 2006;1:153–5. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaskell G, Ten Eyck T, Jackson J, Veltri G. Imagining nanotechnology: cultural support for technological innovation in Europe and the United States. Public Underst Sci. 2005;14:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howard CV, Ikah DSK. Nanotechnology and nanoparticle toxicity: a case for precaution. In: Hunt G, Mehta M, editors. Nanotechnology: Risk, Ethics, and Law. London, UK: Earthscan; 2006. pp. 154–66. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuzma J, Besley JC. Ethics of risk analysis and regulatory review: from bio- to nanotechnology. Nanoethics. 2008;2:149–62. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nisbet MC, Lewenstein BV. Biotechnology and the American media: the policy process and the elite press, 1970 to 1999. Sci Commun. 2002;23:359–91. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nisbet MC. Knowledge into action: framing the debates over climate change and poverty. In: D'Angelo P, Kuypers JA, editors. Doing News Framing Analysis: E. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010. pp. 43–83. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gamson WA. Talking Politics. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorss JB, Lewenstein BV. Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association. New York, NY: 2005. May 26–30, The salience of small: nanotechnology coverage in the American Press, 1986–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman SM, Egolf BP. Nanotechnology: risks and the media. IEEE Technol Soc Mag. 2005;Winter:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson A, Allan S, Petersen A, Wilkinson C. The framing of nanotechnologies in the British newspaper press. Sci Commun. 2005;27:200–20. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkinson C, Allan S, Anderson A, Petersen A. From uncertainty to risk? Scientific and news media portrayals of nanoparticle safety. Health Risk Soc. 2007;38:145–57. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weaver DA, Lively E, Bimber B. Searching for a frame: news media tell the story of technological progress, risk, and regulation. Sci. Commun. 2009;31:139–66. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt Kjaergaard R. Making a small country count: nanotechnology in Danish newspapers from 1996 to 2006. Public Underst. Sci. 2010;19:80–97. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ebeling MFE. Mediating uncertainty: communicating the financial risks of nanotechnologies. Sci Commun. 2008;29:335–61. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilkinson C, Allan S, Anderson A, Petersen A. From uncertainty to risk? Scientific and news media portrayals of nanoparticle safety. Health Risk Soc. 2007;9:145–57. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Satterfield T, Kandlikar M, Beaudrie CE, Conti J, Herr Harthorn B. Anticipating the perceived risk of nanotechnologies. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:752–8. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peter D Hart Research Associates. Nanotechnology, Synthetic Biology, & Public Opinion. Washington, DC: Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheufele DA, Corley EA, Shih T-j, Dalrymple KE, Ho SS. Religious beliefs and public attitudes toward nanotechnology in Europe and the United States. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:91–4. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Royal Society and The Royal Academy of Engineering. Nanoscience and Nanotechnologies: Opportunities and Uncertainties. London, UK: Royal Society and The Royal Academy of Engineering; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Priest S. The North American opinion climate for nanotechnology and its products: opportunities and challenges. J Nanopart Res. 2006;8:563–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nanotechnology and Society Survey Project. Perception of Nanotechnology Among General Public in Japan. Tsukuba, Japan: Nanotechnology Research Institute; 2006. (updated 2006; cited). Available from http://www.nanoworld.jp/apnw/articles/library4/pdf/4-6.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vandermoere F, Blanchemanche S, Bieberstein A, Marette S, Roosen J. The morality of attitudes toward nanotechnology: about God, techno-scientific progress, and interfering with nature. J Nanopart Res. 2010;12:373–81. doi: 10.1007/s11051-009-9809-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vandermoere F, Blanchemanche S, Bieberstein A, Marette S, Roosen J. The public understanding of nanotechnology in the food domain: the hidden role of views on science, technology, and nature. Public Underst Sci. 2009;20:195–206. doi: 10.1177/0963662509350139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smiley Smith SE, Hosgood HD, Michelson ES, Stowe MH. Americans’ nanotechnology risk perception. J Indust Eco. 2008;12:459–73. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stampfli N, Siegrist M, Kastenholz H. Acceptance of nanotechnology in food and food packaging: a path model analysis. J Risk Res. 2010;13:353–65. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siegrist M, Keller C, Kastenholz H, Frey S, Wiek A. Laypeople0s and experts0 perception of nanotechnology hazards. Risk Anal. 2007;27:59–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. Public Praises Science; Scientists Fault Public, Media. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center for the People and the Press; 2009. (updated 9 July 2009; cited). Available from http://people-press.org/reports/pdf/528.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Royal Society. Factors Affecting Science Communication. A Survey of Scientists and Engineers. London, UK: The Royal Society; 2006. Available from http://royalsociety.org/page.asp?id¼3180. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sturgis P, Allum N. Science in society: re-evaluating the deficit model of public attitudes. Public Underst Sci. 2004;13:55–74. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bauer MW, Allum N, Miller S. What can we learn from 25 years of PUS survey research? Liberating and expanding the agenda. Public Underst Sci. 2007;16:79–95. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davies SR. Constructing communication: talking to scientists about talking to the public. Sci Commun. 2008;29:413–34. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frewer LJ, Hunt S, Brennan M, Kuznesof S, Ness M, Ritson C. The views of scientific experts on how the public conceptualize uncertainty. J Risk Res. 2003;6:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peter D. Report Findings: Based on a National Survey of Adults. Washington, DC: Project on Emerging Technologies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Siegrist M. Factors influencing public acceptance of innovative food technologies and products. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2008;19:603–8. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Earle TC, Siegrist M, Gutscher H. Trust, risk perception and the TCC model of cooperation. In: Siegrist M, Earle TC, Gutscher H, editors. Trust in Cooperative Risk Management: Uncertainty and Scepticism in the Public Mind. London, UK: Earthscan; 2007. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nisbet MC, Goidel RK. Understanding citizen perceptions of science controversy: bridging the ethnographic-survey research divide. Public Underst Sci. 2007;16:421–40. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kahan DM. Nanotechnology and society: the evolution of risk perceptions. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:705–6. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cook AJ, Fairweather JR. Intentions of New Zealanders to purchase lamb or beef made using nanotechnology. Br Food J. 2007;109:675–88. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Conner M, Armitage CJ. Extending the theory of planned behavior: a review and avenues for further research. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1998;28:1429–64. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Human Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Slovic P. Trust, emotion, sex, politics, and science: Surveying the risk-assessment battlefield (reprinted from Environment, ethics, and behavior, 277–313, 1997) Risk Anal. 1999;19:689–701. doi: 10.1023/a:1007041821623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Corley E, Scheufele DA, Hu Q. Of risks and regulations: How leading US nanoscientists form policy stances about nanotechnology. J Nanopart Res. 2010;11:1573–85. doi: 10.1007/s11051-009-9671-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nisbet MC, Scheufele DA. The future of public engagement. Scientist. 2007:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nisbet MC. Communicating climate change why frames matter for public engagement. Environment. 2009;51:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mandel G, Braman D, Kahan DM. Cultural cognition and synthetic biology risk perceptions: a preliminary analysis. SSRN eLibrary; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kahan DM, Braman D, Mandel G. Risk and culture: Is Synthetic biology different? SSRN eLibrary; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bauer MW. Distinguishing red and green biotechnology: cultivation effects of the elite press. Int J Public Opin Res. 2005;17:63–89. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dillman DA, Smythe JD, Christian LM. Internet, Mail and Mixed- Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Hobken, NJ: Wiley and Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 78.AAPOR Executive Council Task Force. Deerfield, IL: AAPORT; AAPOR Report on Online Panels. (updated March 2010, cited). Available from http://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Committee_and_ Task_Force_Reports/2556.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peter D. Awareness of and Attitudes Toward Nanotechnology and Federal Regulatory Agencies. Washington, DC: Project on Emerging Technologies; 2007. [Google Scholar]