Abstract

Context:

Oral contraceptive (OC) use is common, but bone changes associated with use of contemporary OC remain unclear.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to compare bone mineral density (BMD) change in adolescent and young adult OC users and discontinuers of two estrogen doses, relative to nonusers.

Design and Setting:

This was a prospective cohort study, Group Health Cooperative.

Participants:

Participants included 606 women aged 14–30 yr (50% adolescents aged 14–18 yr): 389 OC users [62% 30–35 μg ethinyl estradiol (EE)] and 217 age-similar nonusers; there were 172 OC discontinuers. The 24-month retention was 78%.

Main Outcome Measure:

The main outcome measure was BMD measured at 6-month intervals for 24–36 months.

Results:

After 24 months, adolescents using 30–35 μg EE OCs, but not those using lower-dose OCs, had significantly smaller adjusted mean percentage BMD gains than nonusers at the spine [group means (95% confidence interval for between group differences) 1.32 vs. 2.26% (−1.89, −0.13%)] and whole body [1.45 vs. 2.03% (−1.29%, −0.13%)]. Adolescents who discontinued 30–35 μg EE OC showed significantly smaller gains than nonusers at the spine after 12 months [0.51 vs. 1.72% (−2.38%, −0.30%)]. Young adult OC users did not differ from nonusers. However, OC discontinuers of both doses differed significantly from nonusers at the spine 12 months after discontinuation [−1.32% < 30 μg EE, −0.92% 30–35 μg EE vs. +0.27% nonusers (−2.48, −0.54, and −1.94%, −0.55%, respectively)]. Results were similar for mean absolute BMD change (grams per square centimeter).

Conclusions:

Both OC use and discontinuation were associated with BMD losses/smaller gains relative to nonusers (differences < 2% after 12–24 months for all skeletal sites). The clinical significance of these results regarding future fracture risk is unknown. Study of longer-term trends after discontinuation is needed.

Optimal bone development in the first 3 decades of life is critical to prevention of fractures at older ages (1, 2). Although many factors influence the process of bone accrual, gonadal hormones, particularly estrogen, exert profound and complex effects on bone growth and maturation from puberty onward (3, 4). As the leading method of contraception in the United States and worldwide, combined oral contraceptives (OC) are common, often long-term, exposures that alter the normal hormonal milieu. Their use most often occurs at ages when bones are achieving and consolidating their maximum strength.

Studies to date of OC use and bone health have yielded mixed results. There is evidence in perimenopausal women (5, 6) and in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea (7) that OC use improves bone density. However, impacts on bone for the majority of healthy adolescent and young adult women using today's OC formulations remain unclear. Some investigators report OC benefits or no differences in bone density from nonusers (8–12), but others have reported adverse impacts on bone mass accrual (13–20). It can be assumed that differing results reflect, in part, differences in study populations and methods. But this complex association also is likely to be affected by factors such as age at use, OC dose and constituents, and duration of exposure. Because changes in cycling and ovulation occur when OC use is stopped (21, 22) and because ovulatory disturbances may be associated with bone loss (23), bone density changes after OC discontinuation also merit consideration.

We report the results of a prospective study of long-term changes in bone mineral density (BMD) in a cohort of 606 adolescent and young adult OC users and nonusers. We included consideration of age, OC estrogen dose, and duration of use. We also evaluated bone density changes in women discontinuing OC use.

Subjects and Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted at the Group Health Research Institute, Group Health Cooperative. Group Health is a mixed-model managed health care system serving Washington state and western Idaho. During study recruitment (October 2005 through December 2007), approximately 40,000 women enrollees were between the ages of 14 and 30 yr, the target age group. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by Group Health's Human Subjects Committee, and all participants provided written informed consent (with assent from minors following written parental consent).

Study participants

Detailed study sampling and recruitment methods are provided in an earlier report on the baseline parameters (24). Briefly, we selected potential participants from the health plan's computerized data files using a population-based sampling strategy with a targeted recruitment of 600 women.

The sampling frame was structured to recruit 200 OC users and 100 nonusers in two equal-sized age strata: adolescent girls aged 14–18 yr and young adult women aged 19–30 yr. The monthly samples used the Group Health pharmacy data files to identify women filling OC prescriptions and to classify women by OC estrogen pill strength [30–35 μg ethinyl estradiol (EE) and < 30 μg EE] and initiating vs. prevalent use (<3 months of use, 3+ months of use). From the plan's enrollment data files, we concurrently sampled potential comparison women who were not using OC, frequency matching on age and primary care clinic base. Nonusers could have no hormonal contraceptive use within the prior 2 yr. We excluded women who were pregnant, lactating, or intending to become pregnant; women with conditions or using medications known to affect bone density; those using other hormonal methods of contraception; and women planning to leave the area within the next 2 yr.

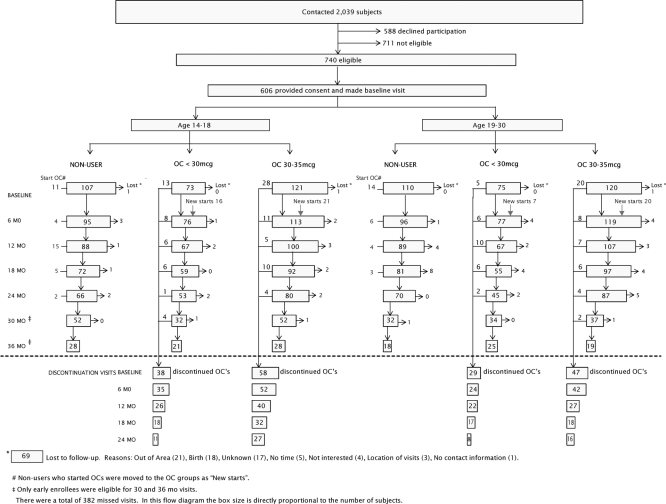

To enroll the study sample, we contacted 2039 potential participants, 1226 women receiving OC prescriptions, and 813 potential comparison women. Of these, 740 women were found to be eligible, 711 were ineligible, and 588 declined participation. A total of 606 eligible participants, 389 current OC users and 217 nonusers, provided informed consent and made baseline visits. Three hundred one participants (50%) were 14–18 yr of age, and 305 were 19–30 yr of age. Of the OC use group, 164 (42%) were initiating OC use and 225 (58%) were prevalent users. We enrolled 148 women (38%) who were using low-dose OC containing less than 30 μg EE, whereas the remaining 241 participants (62%) were using 30–35 μg EE OC (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow of cohort enrollment and follow-up.

Participants came to the Group Health Research Institute clinic in Seattle for their study visits. At enrollment, participants were asked to come every 6 months. The study design incorporated 24 months of follow-up for all participants but allowed up to 36 months for participants who entered the study early. At 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, we completed follow-up visits for 92, 85, 79, and 78% of the cohort, respectively. Additional 30- and 36-month visits were obtained from 240 and 140 participants, respectively (77 and 81% of those invited). Women who were unable to complete a study visit were contacted for subsequent follow-up visits. More than 90% of participants made at least two follow-up visits, and only 69 participants were permanently lost to follow-up. The main reasons for loss to follow-up were pregnancy and moving from the area. A total of 172 women discontinued OC use some time during the study: 96 women aged 14–18 yr and 76 aged 19–30 yr at baseline. The flow of participants from enrollment through the 6-month follow-up intervals, by age and OC status, is summarized in Fig. 1.

Data collection

At baseline and follow-up visits, participants completed questionnaires on health history, reproductive and menstrual history, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, caffeine intake, and demographics. We obtained detailed information about lifetime hormonal contraceptive use via survey and an in-person interview using a life events calendar to assist in pinpointing start and stop dates (25). At each visit we also measured height and weight. We measured BMD at the hip, lumbar spine (L1-L4), and whole body using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. All measurements were performed on the same Hologic Delphi (Hologic, Waltham MA), with precision of 0.72% at the hip and adjustment for navel jewelry as previously reported (26). At the baseline and annual visits, participants also completed a validated food frequency questionnaire that included items on calcium intake and other nutrients (27). Participants received $30 for each visit.

Statistical methods

Our main study outcome was a change in BMD, using adjusted mean percent change at the hip, spine, and whole body. This is the outcome reported in the majority of studies of this association. However, in observational studies, this outcome may be less efficient than absolute change (28). Thus, we also examined bone density change using adjusted mean absolute BMD change (grams per square centimeter) as the outcome. For continuous OC use relative to nonuse, BMD change was calculated relative to baseline. For women discontinuing OC use, we calculated the BMD change after discontinuation relative to BMD at the visit before discontinuation. Because we hypothesized that differences from nonusers would be greatest in adolescents, the group most actively gaining bone, the study was powered to evaluate two age groups separately (ages 14–18 and 19–30 yr) by enriching the sample to attain approximately 50% adolescent participants. To evaluate less than 30 and 30–35 μg EE dose OC formulations, we also oversampled the lower-dose OC users. We adjusted for the following covariates, which were selected a priori or associated with either BMD change or OC use: baseline BMD; race; time-dependent body mass index (BMI) values, weight-bearing physical activity score, calcium intake, current smoking, and self-reported menstruation regularity when not using OC, or pregnant or nursing (always regular; regular but varying by > 10 d; or very irregular/no periods/uncertain).

To use data from the entire follow-up period including multiple visits per woman, we constructed generalized additive mixed models (GAMM), which allowed for nonlinear BMD trajectories, made use of all available follow-up data, and accounted for the correlation among repeated observations for study subjects (29, 30). Results were similar for initial linear regression models and the GAMM.

The GAMM models for OC use vs. nonuse included splines to model trajectories of percent change in BMD as functions of age and cumulative months of each OC exposure. Because we enrolled prevalent OC users as well as new users, cumulative OC use included evaluation of duration of OC use before baseline. We modeled percent change in BMD as a function of OC exposure, including the 5 yr before baseline. Estimates of adjusted mean percent BMD change at each follow-up visit were created using weighted averages of model-based estimates with weights based on the distribution of prior OC use at baseline. Similar analytic methods were used to examine adjusted mean absolute BMD change.

The GAMM models for OC discontinuers vs. nonusers compared adjusted mean BMD percent change after discontinuation. Models included spline functions that allowed BMD percent change to depend on the cumulative exposure and OC dose used before discontinuation as well as the length of elapsed time since discontinuation. The models were adjusted for the same covariates as for OC use. Model estimates were obtained for cumulative OC exposures before discontinuation of 1–24 months for 14–18 yr olds and 1–48 months for 19–30 yr olds. Estimates of adjusted percent change after discontinuation were weighted by the distribution of cumulative exposure observed in our cohort. Again, models using absolute BMD change after discontinuation were constructed using the same modeling strategies.

The GAMM models were constructed for each age group and skeletal site (hip, spine, whole body) using the gamm function in the R software package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). In each model, the trajectories of BMD percent change and BMD absolute change for the two OC dose exposures were compared with trajectories for nonusers. For the percent change estimates, we calculated 95% confidence limits based on the percentiles of 2.5 and 97.5 of 1000 bootstrap replications. We evaluated the statistical significance of between-group differences (user vs. nonuser; discontinuer vs. nonuser) at the α = 0.05 level by examining whether two-sided bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for the between-group differences contained zero. We report the adjusted mean percent change in BMD, with the 95% bootstrap confidence limits for significant between-group differences in brackets. For the percentage change differences found to be significant, we also report the mean absolute BMD change estimates.

A total of 606 baseline visits and 2402 follow-up visits were completed, for a total of 3008 study visits. We excluded 67 follow-up visits during which OC use was restarted after discontinuation and 11 visits during which BMD was not measured. The remaining 2930 follow-up visits were classified as a nonuser (n = 864), user (n = 1636), or discontinuer (n = 430) visit and included in analyses.

Results

Study sample

Baseline characteristics of the cohort, by age group and OC exposure status, are shown in Table 1. Compared with nonusers, OC users in both age groups were more likely to be white, be married, smoke, have navel jewelry, and be older and more physically active. Baseline BMI also was lower for OC users. Mean BMD at baseline was somewhat higher for adolescent OC users vs. nonusers and somewhat lower for women 19–30 yr of age. The hip and spine z-scores for the cohort were very close to a normal distribution (mean 0, sd 1). Mean use of the current OC was 9 months for adolescents and 18 months for young adult women, with shorter duration in the lower-dose groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by age group and OC exposure status at baseline

| OC status | Adolescents aged 14–18 yr (n = 301) |

Young women aged 19–30 yr (n = 305) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC user (n = 194) | OC nonuser (n = 107)a | OC user (n = 195) | OC nonuser (n = 110)a | |

| n (weighted %)b | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 4 (1.1) | 8 (7.5) | 13 (7.4) | 14 (12.7) |

| Black/African American | 7 (3.4) | 8 (7.5) | 4 (0.2) | 5 (4.5) |

| White | 157 (85.4) | 68 (64.2) | 153 (81.6) | 72 (65.5) |

| Other | 26 (10.1) | 22 (20.8) | 24 (10.8) | 19 (17.3) |

| Education high school or less or GED | 179 (90.8) | 182 (93.4) | 8 (3.6) | 4 (3.6) |

| Never married | 188 (95.9) | 106 (99.1) | 133 (68.1) | 88 (80.0) |

| Current smoker | 9 (5.9) | 5 (4.7) | 23 (13.1) | 6 (5.5) |

| Relative with fracture | 31 (22.3) | 13 (16.9) | 43 (30.0) | 22 (30.1) |

| Ever pregnant | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.9) | 26 (14.1) | 17 (15.6) |

| Regular periods | 160 (80.6) | 89 (83.2) | 173 (87.7) | 102 (92.7) |

| Navel jewelry | 23 (15.3) | 6 (5.6) | 18 (12.4) | 7 (6.4) |

| Current OC 30–35 μg EE | 121 (86.6) | NA | 120 (89.3) | NA |

| Weighted mean (se)b | ||||

| Age (yr) | 16.8 (0.1) | 16.4 (0.1) | 24.6 (0.3) | 24.1 (0.3) |

| Age at menarche (yr) | 12.1 (0.1) | 12.4 (0.1) | 12.7 (0.1) | 12.5 (0.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 (0.4) | 23.9 (0.4) | 24.3 (0.5) | 25.2 (0.5) |

| Weight-bearing physical activity | 1189 (57) | 1178 (61) | 839 (56) | 820 (48) |

| Dietary calcium (mg/d) | 1167 (49) | 1181 (58) | 1045 (49) | 1001 (48) |

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 1.5 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.2) | 9.1 (1.2) | 5.7 (0.8) |

| Protein, total (g/d) | 74 (3) | 72 (3) | 70 (2) | 74 (3) |

| Current OC use (months) | 9.0 (0.8) | NA | 19.2 (2.5) | NA |

| Less than 30 μg EE dose | 4.1 (0.5) | NA | 14.5 (2.1) | NA |

| 30–35 μg EE dose | 9.8 (1) | NA | 19.7 (2.8) | NA |

| Total hip BMD (g/cm2) | 0.995 (0.010) | 0.994 (0.010) | 0.980 (0.012) | 0.994 (0.010) |

| Spine BMD (g/cm2) | 1.011 (0.010) | 1.001 (0.008) | 1.026 (0.011) | 1.044 (0.011) |

| Whole-body BMD (g/cm2) | 1.090 (0.007) | 1.083 (0.007) | 1.112 (0.008) | 1.112 (0.008) |

NA, Not applicable.

Nonusers had no OC use in the prior 2 yr. They were allowed some use prior to that time: in adolescents, 94% of the 107 nonusers had no prior OC use at all; only one had more than 3 months (11.9 months) of use before the 2 most recent years. In young adult women, 64% of the 110 nonuser participants had no prior OC use at all; only nine participants had more than 36 months of use before the 2 most recent years (range 37–86 months).

The n are actual number of participants; percentages and means are weighted to account for the study sampling frame.

Changes in BMD in adolescents using and discontinuing OC

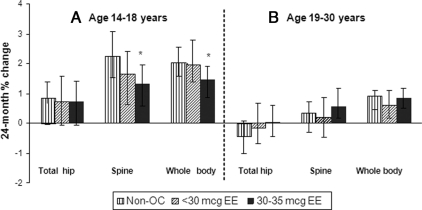

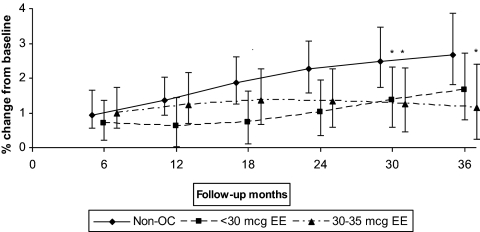

Adolescent nonusers showed adjusted 24-month mean BMD gains of approximately 0.67, 2.26, and 2.03% at the hip, spine, and whole body sites, respectively (Fig. 2A). Both OC dose groups showed similar gains at the hip and smaller gains at the spine and whole body than nonusers. Between-group differences at 24 months were statistically significant for 30–35 μg EE OC users vs. nonusers at the spine [1.32 vs. 2.26% (−1.89%, −0.13%)] and whole body [1.45% vs. 2.03% (−1.29%, −0.13%)] (Fig. 2A). These differences continued out to 36 months of follow-up. Results were similar for mean absolute BMD change (grams per square centimeter): for the spine, mean absolute change was 0.0115 vs. 0.0216 g/cm2 for OC users vs. nonusers; and for the whole body, 0.0146 vs. 0.0214 g/cm2. Because most of the prospective studies to date have evaluated participants who initiated OC use when enrolled in the study, we also examined BMD changes occurring just in OC initiators (excluding prevalent OC users). The trajectories in mean percentage BMD change at the spine for the adolescent OC initiators vs. nonusers are shown in Fig. 3. In this subgroup, low-dose initiators show smaller gains than nonusers for the first 24 months, with the high-dose OC group trending lower than nonusers further out in the follow-up interval. After 30 months of follow-up, the two OC use groups were similar; both had significantly smaller gains compared with the nonusers.

Fig. 2.

Adjusted 24-month mean BMD percent change, by age group, OC dose, and skeletal site. Data were adjusted for baseline BMD, race, time-dependent BMI, weight-bearing physical activity score, calcium intake, current smoking, and menstruation regularity. The 24-month results were based on GAMM using all 1260 follow-up visits (434 non-OC, 313 less than 30 μg EE, and 513 30–35 μg EE) for 14–18 year olds and 1240 follow-up visits (430 non-OC, 297 less than 30 μg EE, 513 30–35 μg EE) for 19–30 year olds. *, Statistically significant difference from nonusers, based on 95% bootstrap confidence interval for between-group differences.

Fig. 3.

Adjusted mean BMD percent change for 14- to 18-yr-old OC initiators vs. nonuser, spine. Data were adjusted for baseline BMD, race, time-dependent BMI, weight-bearing physical activity score, calcium intake, current smoking, and menstruation regularity. The results were based on GAMM using all 1260 follow-up visits (434 non-OC, 313 less than 30 μg EE, and 513 30–35μg EE) for 14–18 year olds and 1240 follow-up visits (430 non-OC, 297 less than 30 μg EE, 513 30–35 μg EE) for 19–30 year olds and assuming OC initiation at baseline. *, Statistically significant difference from nonusers, based on 95% bootstrap confidence interval for between-group differences.

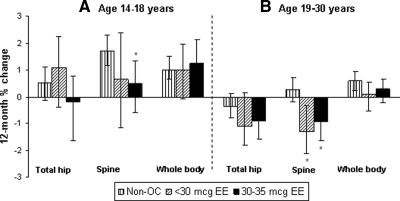

Adolescents who discontinued both EE doses showed smaller gains than nonusers at the spine, with significant differences for 30–35 μg EE dose users at 12 months after discontinuation [0.51 vs. 1.72% (−2.38, −0.30%)] (Fig. 4A). These differences persisted out to 24 months after discontinuation. The changes in bone density after discontinuation did not vary by the duration of OC use before discontinuation. Results were similar with mean absolute BMD change as the outcome: 0.0051 g/cm2 for OC users vs. 0.0166 g/cm2 for nonusers.

Fig. 4.

Adjusted 12-month adjusted mean BMD percent change after discontinuation by age group, OC dose, and skeletal site. Data were adjusted for baseline BMD, race, time-dependent BMI, weight-bearing physical activity score, calcium intake, current smoking, and menstruation regularity. The 12-month results are based on GAMM using all 606 follow-up visits (434 non-OC, 62 less than 30 μg EE, and 110 30–35μg EE) for 14–18 year olds and 688 follow-up visits (430 non-OC, 105 less than 30 μg EE, 153 30–35 μg EE) for 19–30 year olds. *, Statistically significant difference from nonusers, based on 95% bootstrap confidence interval for between-group differences.

Changes in BMD in young adult women using and discontinuing OC

At 24 months of follow-up, young adult participants showed small BMD losses at the hip and smaller gains than adolescent participants at the spine and whole body (Fig. 2B). Among nonusers, adjusted 24-month mean BMD percent changes were −0.42, 0.35, and 0.90% at the hip, spine, and whole body, respectively. There were no significant differences between OC users and nonusers for either OC dose group at any skeletal site (Fig. 2B), including examining just OC initiators (data not shown).

Young adult discontinuers in both OC dose groups showed larger BMD losses or smaller gains relative to nonusers at all skeletal sites. These were significant for both less than 30 μg EE and 30–35 μg EE users vs. nonusers at the spine after 12 months [−1.32 and −0.92 vs. 0.27% (−2.48, −0.54 and −1.94, −0.55%, respectively)] (Fig. 4B). Significant between-group differences persisted for the remaining available follow-up. Changes in bone density after discontinuation did not vary by the duration of OC use before discontinuation except for the spine, in which 12-month percent BMD losses were greater with prior OC use of more than 24 months. Results using mean absolute BMD change were similar: −0.0124 and −0.0100 g/cm2 for less than 30 μg EE and 30–35 μg EE OCs, respectively, vs. 0.0026 g/cm2 for nonusers.

Discussion

The current prospective evaluation of a cohort of more than 600 women in the process of gaining bone suggests that the association between current OC formulations and bone density is subject to some influence by age, estrogen dose, length of use, and skeletal site. In particular, those women aged 14–18 yr on the higher EE dose of current OC formulations showed approximately 1% less bone gain over 2 yr in the spine and total body than did the same-aged young women either on lower-dose OC or not on hormonal contraception. Among young adult women, mean BMD changes for OC users in both OC dose groups were similar to nonusers for all available follow-up.

Adolescents in this cohort who discontinued 30–35 μg EE OC also showed significantly smaller BMD gains at the spine than nonusers 12–24 months after discontinuation. In addition, among young adult participants, we observed BMD losses at the spine for OC discontinuers of both OC EE doses vs. small gains for nonusers after 12 months.

For adolescent participants, our results were in accord with most of the available longitudinal studies focused on teen OC users (10, 13, 15, 17). A 2008 report reported no difference between users of a 20 μg EE OC and nonusers after 24 months of follow-up (10). Two other studies with longer follow-up (4–5 yr) and including substantial proportions of 30–35 μg OC users reported significantly smaller increases vs. nonusers in spine and femoral neck bone mineral content (17) and distal radius BMD (15). However, a recently reported crossover study found that 15- to 18-yr-old adolescents had losses or smaller gains in spine BMD during 9 months' use of a 15-μg EE dose but not during the use of a 30-μg EE dose (13). We observed a similar pattern for our OC initiators (Fig. 3), in which less than 30-μg EE users evidenced smaller gains compared with nonusers up to 24 months of use but trended toward nonusers subsequently, whereas higher EE dose users trended away from nonusers only after longer follow-up.

Longitudinal studies that focus on young adults and/or older adolescents are both more numerous and more varied in their findings. The two studies reporting the largest differences between OC users and nonusers are the following: a 1995 report of a 5-yr study of 19- to 22-yr-old women in which OC users had no changes in mean spine BMD, whereas nonusers showed a 7.8% gain (14); and a 3-yr study of women aged 16–33 yr, in which OC users showed BMD losses of −0.54 and −1.29% at the spine and femoral neck, whereas nonusers had gains of 1.94 and 0.61% (16). However, other prospective studies of women of these ages observed no adverse impacts on bone density with OC use (8, 9, 11, 12, 31). We also saw no differences between young adult OC users and nonusers.

The disparate study findings to date may result, in part, from the complex actions of OC. Estrogens (and potential estrogenic actions of OC) have beneficial effects on bone density in remodeling bone through several mechanisms: 1) promoting osteoclast apoptosis; 2) decreasing receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand, which reduces osteoclast number; and 3) reducing cytokine activity, thereby reducing osteoclast activity. These effects would act to increase bone density. Estrogens also oppose periosteal growth, which eventually results in smaller bones (32). Other potential negative effects of OC may result from the increased hepatic production of SHBG (with decreased androgens) and decreased IGF (33–35). The lower androgen levels may further inhibit periosteal expansion. Higher-dose OC have greater suppression of IGF (36), which could particularly impact adolescents because they have higher IGF levels than the older subjects (37).

The widespread and often lengthy use of OC for many young women, along with a number of previous reports suggesting adverse impacts on bone (13, 14, 16, 17, 19), lend added importance to bone changes after discontinuation. We found no other reports on bone changes after OC discontinuation, although we and others have evaluated bone changes after discontinuation of another hormonal contraceptive, injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera, Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY), and observed rapid and substantial gains in bone density after discontinuation (16, 38–40). The results we report here suggest the need for further investigation of longer-term trends after OC discontinuation.

The current study offers a number of strengths. This is a sizable sample that was structured to evaluate both adolescent and young adult age groups and the two most commonly prescribed estrogen OC strengths within the same cohort. We selected our comparison group from the same defined population, thus minimizing bias and comparability issues, and we examined percentage and absolute BMD change at multiple skeletal sites. A major threat to the internal validity of prospective studies is attrition from the cohort, and the study follow-up was excellent. We also were able to keep following up study participants who discontinued OC. We incorporated a robust and flexible analytic strategy that allowed for the use of all of the available follow-up data, accommodated the possible nonlinear trajectories of bone change at these ages, and accounted for the role of numerous covariates and within-subject correlation. Enrolling both prevalent and initiating OC users allowed us to evaluate durations of use beyond the study follow-up interval and to better assess bone changes after discontinuation.

One potential limitation of these data, given our results, is that a longer amount of follow-up time after OC discontinuation would have been desirable, particularly for our young adult participants who are nearing the end of their period for bone accrual. Also, evaluating the potential role of varying OC progestins was beyond the scope of this study. These are more complex constituents of today's OC formulations that may contribute to some of the differing study results. The two prospective studies reporting the largest between-group differences between OC users and nonusers evaluated 20 μg EE OC formulations for which desogestrel was the progestin (14, 16), whereas levonorgestrel was the progestin in a longer-term study reporting no association between 20 μg EE OC use and bone change (10). In the current study, in which we saw no association with lower-dose OC, the main progestins (>85%) were levonorgestrel and norethindrone acetate. Finally, we do not have information aside from age on nonparticipants, but some degree of selection bias may have resulted. However, the mean BMD of our participants was similar to published national reference ranges, and cohort retention was excellent.

In considering the clinical importance of these results, we note that statistically significant undesirable BMD differences for OC exposure were seen in only one age/OC estrogen group. These approximately 0.5–1% differences in percentage change between OC users and nonusers were much smaller and less immediate than the BMD declines reported for users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera) contraception (14–17). Our follow-up of OC discontinuers also showed some statistically significant smaller gains, or losses vs. gains, for OC discontinuers vs. nonusers. These still were quite small (1% to <2%) and may reflect residual confounding. However, bone health may merit inclusion as a topic in counseling women of these ages who elect longer-term OC use.

In summary, the current study investigated the possible effects of OCs on bone density in the age groups with the highest use and evaluated the most commonly prescribed OC estrogen doses. The statistically significant changes we observed were small, and thus, the results are generally reassuring. However, further research in young women from diverse study populations as well as research on longer-term trends after discontinuation and on the association between OC use and fracture is needed.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Patty Yarbro, project manager; Holly Roberts and Linda Wehnes, bone densitometrists; Jane Grafton, programmer; Kelli O'Hara, Shirley Meyer, and Mary Lyons, study recruiters; and our study participants.

This work was supported by Grant 1R01-HD31165-11 (D.S., principal investigator) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. J.M.B. was supported by Grant T-32 AG027677 (A.Z.L., principal investigator) from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no disclosures.

Footnotes

- BMD

- Bone mineral density

- BMI

- body mass index

- EE

- ethinyl estradiol

- GAMM

- generalized additive mixed models

- OC

- oral contraceptive.

References

- 1. Melton LJ, Cooper C. 2001. Magnitude and impact of osteoporosis and fractures. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Kelsey J. eds. Osteoporosis. 2nd ed San Diego: Academic Press; 557–567 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nelson DA, Norris SA, Gilsanz V. 2006. Childhood and adolescence. In: Favus MJ, Shane E, Kleerekoper M. eds. Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. Washington, DC: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; 55–61 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bachrach LK. 2001. Acquisition of optimal bone mass in childhood and adolescence. Trends Endocrinol Metab 12:22–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Komm BS, Bodine PVN. 2001. Regulation of bone cell function by estrogens. In: Marcus R, Feldman D, Kelsey J. eds. Osteoporosis. 2nd ed San Diego: Academic Press; 305–340 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gambacciani M, Spinetti A, Taponeco F, Cappagli B, Piaggesi L, Fioretti P. 1994. Longitudinal evaluation of perimenopausal vertebral bone loss: effects of a low-dose oral contraceptive preparation on bone mineral density and metabolism. Obstet Gynecol 83:392–396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Michaëlsson K, Baron JA, Farahmand BY, Persson I, Ljunghall S. 1999. Oral-contraceptive use and risk of hip fracture: a case-control study. Lancet 353:1481–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Warren MP, Miller KK, Olson WH, Grinspoon SK, Friedman AJ. 2005. Effects of an oral contraceptive (norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol) on bone mineral density in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea and osteopenia: an open-label extension of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Contraception 72:206–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reed SD, Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. 2003. Longitudinal changes in bone density in relation to oral contraceptive use. Contraception 68:177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Recker RR, Davies KM, Hinders SM, Heaney RP, Stegman MR, Kimmel DB. 1992. Bone gain in young adult women. JAMA 268:2403–2408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cromer BA, Bonny AE, Stager M, Lazebnik R, Rome E, Ziegler J, Camlin-Shingler K, Secic M. 2008. Bone mineral density in adolescent females using injectable or oral contraceptives: a 24-month prospective study. Fertil Steril 90:2060–2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nappi C, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Greco E, Tommaselli GA, Giordano E, Guida M. 2005. Effects of an oral contraceptive containing drospirenone on bone turnover and bone mineral density. Obstet Gynecol 105:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lara-Torre E, Edwards CP, Perlman S, Hertweck SP. 2004. Bone mineral density in adolescent females using depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 17:17–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stepan J, Cibula D, Skrenkova J, Hill M. 2009. A cross-over study of BMD and markers in adolescent users of combined oral contraceptives with different estrogen content. Proc 31st Annual Meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, Denver, Colorado, 2009 (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 14. Polatti F, Perotti F, Filippa N, Gallina D, Nappi RE. 1995. Bone mass and long-term monophasic oral contraceptive treatment in young women. Contraception 51:221–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beksinska ME, Kleinschmidt I, Smit JA, Farley TM. 2009. Bone mineral density in a cohort of adolescents during use of norethisterone enanthate, depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate or combined oral contraceptives and after discontinuation of norethisterone enanthate. Contraception 79:345–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berenson AB, Rahman M, Breitkopf CR, Bi LX. 2008. Effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and 20-microgram oral contraceptives on bone mineral density. Obstet Gynecol 112:788–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pikkarainen E, Lehtonen-Veromaa M, Möttönen T, Kautiainen H, Viikari J. 2008. Estrogen-progestin contraceptive use during adolescence prevents bone mass acquisition: a 4-year follow-up study. Contraception 78:226–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cromer BA, Stager M, Bonny A, Lazebnik R, Rome E, Ziegler J, Debanne SM. 2004. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, oral contraceptives and bone mineral density in a cohort of adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health 35:434–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hartard M, Kleinmond C, Wiseman M, Weissenbacher ER, Felsenberg D, Erben RG. 2007. Detrimental effect of oral contraceptives on parameters of bone mass and geometry in a cohort of 248 young women. Bone 40:444–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Almstedt Shoepe H, Snow CM. 2005. Oral contraceptive use in young women is associated with lower bone mineral density than that of controls. Osteoporos Int 16:1538–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bracken MB, Hellenbrand KG, Holford TR. 1990. Conception delay after oral contraceptive use: the effect of estrogen dose. Fertil Steril 53:21–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doll H, Vessey M, Painter R. 2001. Return of fertility in nulliparous women after discontinuation of the intrauterine device: comparison with women discontinuing other methods of contraception. BJOG 108:304–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bedford JL, Prior JC, Barr SI. 2010. A prospective exploration of cognitive dietary restraint, subclinical ovulatory disturbances, cortisol, and change in bone density over two years in healthy young women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:3291–3299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scholes D, Ichikawa L, LaCroix AZ, Spangler L, Beasley JM, Reed S, Ott SM. 2010. Oral contraceptive use and bone density in adolescent and young adult women. Contraception 81:35–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marcus AC. 1982. Memory aids in longitudinal health surveys: results from a field experiment. Am J Public Health 72:567–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ott SM, Ichikawa LE, LaCroix AZ, Scholes D. 2009. Navel jewelry artifacts and intravertebral variation in spine bone densitometry in adolescents and young women. J Clin Densitom 12:84–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, Carter RA, Bolton MP, Agurs-Collins T. 1999. Measurement characteristics of the Women's Health Initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol 9:178–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berry DA, Ayers GD. 2006. Symmetrized percent change for treatment comparisons. Am Stat 60:27–31 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ. 1990. Generalized additive models. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman, Hall/CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. eds. 2001. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference and prediction. New York: Springer Science and Business Media, Inc [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berenson AB, Breitkopf CR, Grady JJ, Rickert VI, Thomas A. 2004. Effects of hormonal contraception on bone mineral density after 24 months of use. Obstet Gynecol 103:899–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ., 3rd 2002. Sex steroids and the construction and conservation of the adult skeleton. Endocr Rev 23:279–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coenen CM, Thomas CM, Borm GF, Rolland R. 1995. Comparative evaluation of the androgenicity of four low-dose, fixed-combination oral contraceptives. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud 40(Suppl 2):92–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wiegratz I, Kutschera E, Lee JH, Moore C, Mellinger U, Winkler UH, Kuhl H. 2003. Effect of four different oral contraceptives on various sex hormones and serum-binding globulins. Contraception 67:25–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Greco T, Graham CA, Bancroft J, Tanner A, Doll HA. 2007. The effects of oral contraceptives on androgen levels and their relevance to premenstrual mood and sexual interest: a comparison of two triphasic formulations containing norgestimate and either 35 or 25 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception 76:8–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kam GY, Leung KC, Baxter RC, Ho KK. 2000. Estrogens exert route- and dose-dependent effects on insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-3 and the acid-labile subunit of the IGF ternary complex. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:1918–1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Walsh JS, Eastell R, Peel NF. 2008. Effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone density and bone metabolism before and after peak bone mass: a case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1317–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. 2002. Injectable hormone contraception and bone density: results from a prospective study. Epidemiology 13:581–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, Barlow WE, Ott SM. 2005. Change in bone mineral density among adolescent women using and discontinuing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 159:139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clark MK, Sowers M, Levy B, Nichols S. 2006. Bone mineral density loss and recovery during 48 months in first-time users of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Fertil Steril 86:1466–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]