Abstract

Splicing of the group I intron of the T4 thymidylate synthase (td) gene was uncoupled from translation by introducing stop codons in the upstream exon. This resulted in severe splicing deficiency in vivo. Overexpression of a UGA suppressor tRNA partially rescued splicing, suggesting that this in vitro self-splicing intron requires translation for splicing in vivo. Inhibition of translation by the antibiotics chloramphenicol and spectinomycin also resulted in splicing deficiency. Ribosomal protein S12, a protein with RNA chaperone activity, and CYT-18, a protein that stabilizes the three-dimensional structure of group I introns, efficiently rescued the stop codon mutants. We identified a region in the upstream exon that interferes with splicing. Point mutations in this region efficiently alleviate the effect of a nonsense codon. We infer from these results that the ribosome acts as an RNA chaperone to facilitate proper folding of the intron.

Keywords: Group I intron splicing, translation, RNA chaperones

Group I introns occur in ribosomal RNA, tRNA, and in protein encoding genes. Many of these introns are self-splicing in vitro and do not require proteins for activity (Cech 1990). Group I introns fold into a compact defined structure, embedding the 5′ splice-site into a stem (P1), which is docked into the catalytic core of the molecule (Waring et al. 1986; Michel and Westhof 1990; Cech et al. 1994). For group I introns that disrupt rRNAs and tRNAs, it was shown that the exon structure influences folding of P1, and as a consequence, splicing efficiency (Woodson and Cech 1991; Woodson 1992; Woodson and Emerick 1993; Zaug et al. 1993). Exon sequences surrounding the splice sites of pre-mRNAs, however, should be mainly unstructured to ensure efficient translation. Most group I mRNA introns reside in prokaryotes or in eukaryotic organelles where transcription, splicing and translation are linked events. The ribosome might reach a 5′ splice site before the 3′ splice site is even transcribed. This situation clearly requires tight regulation to prevent aberrant translation products. Additionally, many group I introns encode proteins in-frame with the preceding exons, or, as in the T4 phage introns, expressed independently from their own promoters located within the intron (Lazowska et al. 1980; Gott et al. 1988).

RNA catalysis depends on complex tertiary structures. In vivo, many group I introns require splicing factors to promote the correct folding into the catalytically active tertiary structure (Lambowitz and Belfort 1993). In vitro, splicing can occur in the absence of protein factors, but activity is most often limited by incorrectly folded RNA molecules (Walstrum and Uhlenbeck 1990). Two proteins that promote the folding of group I introns, have been extensively studied: the tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase of Neurospora crassa (CYT-18) (Lambowitz and Perlman 1990) and the CBP2 protein from yeast mitochondria (Gampel et al. 1989).

CYT-18 is involved both in charging its cognate tRNA and in promoting splicing of group I introns. CYT-18 is also capable of binding group I introns from other species, like the T4 phage thymidylate synthase (td) and the Tetrahymena thermophila LSU introns. In the latter case, CYT-18 does not bind to the full-size intron, rather, it functionally replaces the P5abc domain, stabilizing the P4–P6 domain (Murphy and Cech 1993; Mohr et al. 1994). CYT-18 binds to group I introns by first contacting the P4–P6 domain to form a scaffold for the assembly of the P3–P9 domain. CYT-18 interacts with both helical domains of the intron on the side opposite to the active site cleft, which accommodates the 5′ splice-site by recognizing the shape of the molecule through contacts with the phosphate backbone (Caprara et al. 1996b). CYT-18 seems not to contact the P1 stem harboring the splice site. It restores splicing in vitro for splicing-defective mutations throughout the intron, except those located in the P1 and P2 stems of the T4 phage td intron (Mohr et al. 1992). In contrast, the CBP2 protein, which facilitates folding of the bI5 intron of yeast mitochondria, does this by assembling the intron core with the P1 domain containing the splice site (Weeks and Cech 1995a,b).

RNA folding encounters two problems: It easily becomes kinetically trapped in inactive conformations and its three dimensional structure is often thermodynamically misfavored over alternative folds. RNA-binding proteins that help overcome these problems by preventing misfolding or by resolving misfolded species are defined as RNA chaperones (Herschlag 1995). While the CYT-18 and CBP2 proteins stabilize a specific RNA structure, several other RNA-binding proteins, such as the nucleocapsid protein of HIV and the hnRNP A1, have been assigned a nonspecific RNA-binding activity. These proteins accelerate ribozyme catalysis in a more general way, and once the RNA is folded, they are no longer needed for activity (Herschlag 1995). Similarly, several ribosomal proteins of Escherichia coli, especially S12, were found to stimulate trans-splicing of the T4 phage td intron in vitro. S12 does not bind strongly or specifically to the intron RNA, but has a rather broad specificity for RNA. Like other RNA chaperones, it facilitates catalysis of the hammerhead ribozyme (Tsuchihashi et al. 1993; Herschlag et al. 1994). S12 was suggested to have RNA chaperone activity (Coetzee et al. 1994).

Aminoglycoside antibiotics, which affect translation accuracy, have been shown to inhibit splicing of group I introns in vitro (von Ahsen et al. 1991). To study the effect of these antibiotics on splicing in vivo, we uncoupled splicing from translation by introducing a nonsense codon in the upstream exon of the td gene. Surprisingly, even in the absence of antibiotics, this stop codon, located 223 nucleotides upstream of the 5′ splice site, reduced in vivo splicing to an undetectable level. Further analysis of this phenomenon revealed that the ribosome plays an essential role in splicing of this mRNA intron in vivo.

Results

Stop codons in the upstream exon of the T4 phage td gene lead to splicing deficiency in vivo

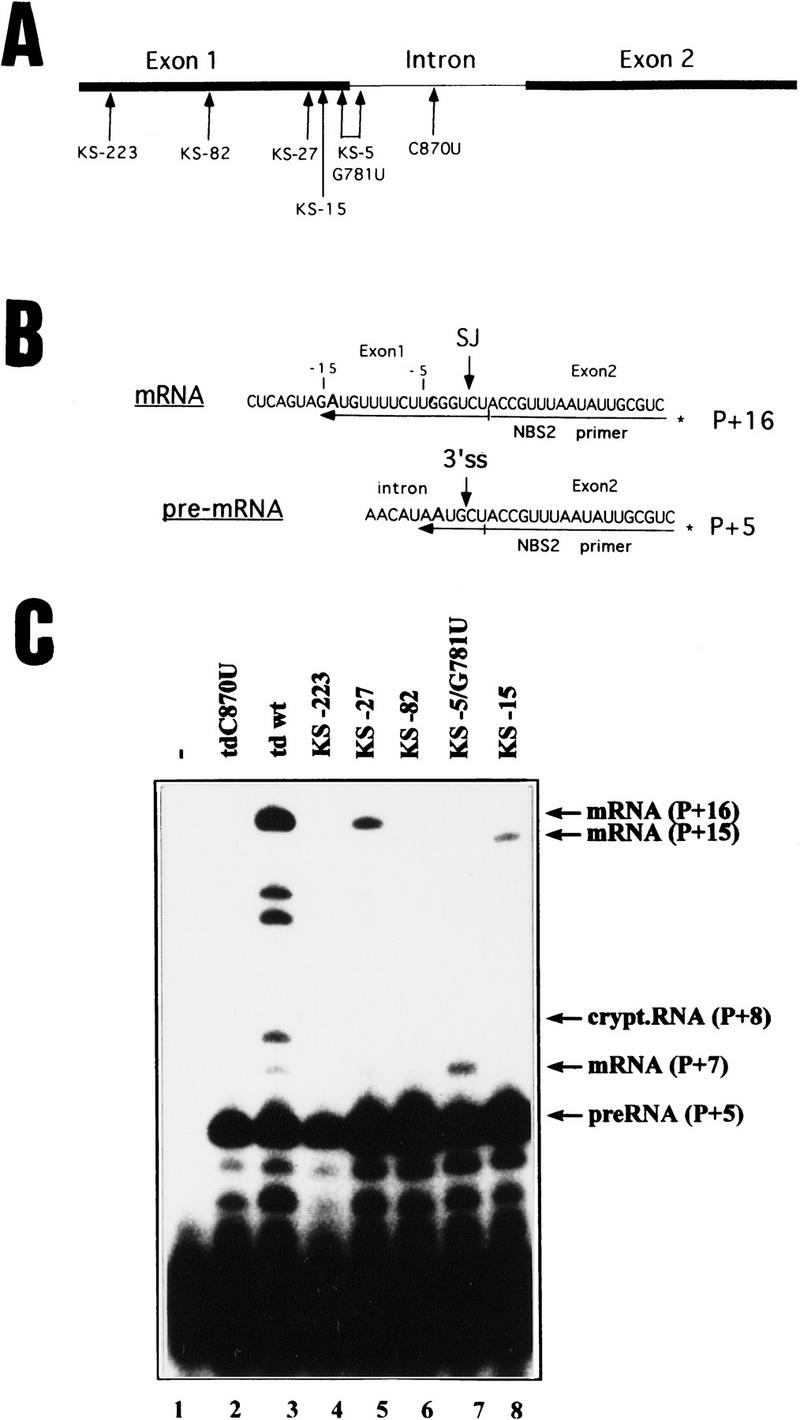

Stop codons were introduced into exon 1 of the td gene at various positions by site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 1A). In vivo, splicing in the mutants containing stop codons was tested via a primer-extension assay (Fig. 1B). Total cellular RNA of E. coli strains transformed with plasmids harboring the T4 td gene was isolated, and the efficiency of splicing was tested by reverse transcription with a primer (NBS2) that hybridizes at the 5′ end of exon 2. In the presence of ddTTP, dATP, dCTP, and dGTP, primer extension stops at the first A of the template after ddTTP is incorporated. Extension of the pre-mRNA results in a product that is 5 nucleotides longer than the primer (P + 5), while the mature mRNA allows the addition of 16 nucleotides (Fig. 1C). To ensure that the NBS2 primer does not hybridize to endogenous E. coli sequences, a strain without the td gene was tested (Fig. 1C, lane 1). As a splicing-deficient control, a td mutant with a mutation in the catalytic core was used (td C870U, Fig. 1C, lane 2; Schroeder et al. 1991). In addition to the mature splicing product, a cryptic splice site is utilized 29 nucleotides upstream of the 5′ splice site, resulting in a P + 8 extension product (Chandry and Belfort 1987). Bands at positions P + 12/13 (Fig. 1C, lane 3) are unidentified products, which may result from a premature stop of reverse transcription. The gel was strongly overexposed during autoradiography to detect low splicing activities. As can be seen in Figure 1C and Table 1, splicing activities in the stop codon mutants are significantly lower than in the wild type, depending on the position of the stop codon. In the mutants, where translation stops 223 and 82 nucleotides upstream of the 5′ splice site, splicing activity is below 1%, whereas the wild-type construct splices to 40%. The closer the stop codon is located to the 5′ splice site, the higher is the splicing activity (Table 1). Stop codons at positions −27, −15, and −5 show 10%, 7%, and 15% splicing, respectively. Mutants KS-5/G781U and KS-15 have altered mRNA sequences and reveal products P + 15 and P + 7 caused by a prior A appearing in the sequence (Fig. 1C, lanes 7, 8). Even when the stop codon is only two codons distant to the 5′ splice site, splicing activity is significantly reduced.

Figure 1.

In vivo splicing of the stop codon mutants. (A) Position of the stop codons introduced into exon 1 of the T4 phage td gene and of the C870U intron mutant. Numbering of nucleotides indicates the distance to the 5′ splice site. For exact sequence of mutations see Table 1. (Solid bars) Exons; (thin lines) intron sequences. (B) Schematic representation of the primer–extension assay for splicing in E. coli. Extension of the 32P-labeled NBS2 primer, which hybridizes to exon 2 sequences, stops at the first A of the template in the presence of dATP, dCTP, dGTP and high concentrations of ddTTP. (P + x) Length of the extension product. pre-RNA is extended by 5 nucleotides (P + 5) and mRNA is extended by 16 nucleotides (P + 16). (SJ) Spliced junction; (3′ ss) 3′ splice site. (C) Primer-extension assay for splicing. The RNAs were isolated from cells containing no td gene (lane 1), the splicing-deficient mutant (td C870U, lane 2), the wild-type gene (lane 3), or the stop codon mutants as indicated (lanes 4–8). For the stop codon mutants KS-15 and KS-5/G781U the reverse transcripts of the mRNA differ in length because of the U to A mutation at position −15 or at position −5 and result in P + 15 and P + 7 extension products, respectively.

Table 1.

Effect of nonsense codons in exon 1 on splicing in vivo

| Mutation

|

Designation

|

Percent mRNA

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Wild-type td | 41 ± 1.6 |

| T546A; G547T | KS-223 | <1 |

| T687A | KS-82 | <1 |

| C742T; A743G | KS-27 | 10 ± 1.9 |

| G754T; T756A | KS-15 | 6.8 ± 2.2 |

| T764A; G781T | KS-5/G781U | 15.4 ± 4.1 |

| C870T | td C870U | <1 |

Quantification of primer extension products. Radioactivity was determined on a PhosphorImager, and splicing activity is given in percent mRNA calculated from (mRNA + cryptic RNA) × 100/(pre-RNA + mRNA + cryptic RNA).

The stop codon mutations do not affect in vitro splicing activity. RNA of the wild type and the stop codon mutants was obtained by in vitro transcription and spliced in vitro as described in Materials and Methods. Splicing activities of the wild type and the stop codon mutants were indistinguishable, showing that the effect observed in vivo is not attributable to a splicing deficiency of the intron itself (data not shown).

Stability of the mRNA is not affected by the stop codons

It was shown that stop codons close to the 5′ end of mRNAs in Bacillus subtilis induce mRNA degradation in vivo (Nilsson et al. 1987). To test whether the effect was attributable to a destabilization of mRNA, an intronless version of the td gene was constructed (tdΔintron) and a UGA codon was introduced at position −82 (tdΔintron/KS−82). Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.2, then transcription was inhibited by the addition of rifampicin. Time points were taken up to 40 min, and mRNA amounts were compared via a primer-extension assay for the intronless construct with and without the nonsense codon (Fig. 2). For the primer-extension assay, the same amounts of total cellular RNA were used. No differences in the amounts of td-specific mRNA between both constructs are detectable, indicating that the nonsense codon does not affect mRNA stability and that the effect seen on splicing is not attributable to a rapid degradation of the spliced mRNA.

Figure 2.

Stability of a nonsense codon containing mRNA. Comparison of the mRNA stability of the intronless mutants without and with a stop codon at position −82. The intronless constructs were grown to exponential phase and samples were taken before the addition of rifampicin (0′) and after its addition (1′ to 40′). mRNA amounts were assayed via primer-extension assay. (Lane 1) C870U mutant; (lane 2) wild type; (lanes 3–8) intronless td gene; (lanes 9–14) intronless td gene with stop codon at position −82.

The protein encoded by exon 1 is not required for splicing

Translation of the unspliced pre-mRNA is terminated at the 5′ splice site, because a UAA stop codon is at the very beginning of the intron, and results in a protein product called NH2-TS (Belfort et al. 1987). Introducing stop codons in the upstream exon prevents synthesis of this protein. To test whether the translation product of exon 1 is essential for splicing, we extensively altered its amino acid sequence by deleting nucleotide −182 of exon 1, causing a frameshift, and by inserting a C 3′ of G-18, restoring the original reading frame before the 5′ splice site (Fig. 3A). This results in a protein with an altered sequence over 55 amino acids, most probably disrupting its function, as this part of the protein is highly conserved between species (Carreras and Santi 1995). In vivo splicing activity of this construct was tested and found to be twice as high as for the wild type; in addition, the cryptic splice product (P + 8) was also strongly enhanced (Fig. 3B, lane 7). The fact that splicing takes place in the absence of an active thymidylate synthase (TS) suggests that the protein product of exon 1 is not essential for splicing. However, it remains possible that some portion of the polypeptide could be required. The fact that both splicing and cryptic splicing are enhanced as compared to the wild type suggests further that this protein regulates expression of the gene. It is known that human and E. coli TS interact with their own mRNAs, repressing translation (Chu et al. 1993; Voeller et al. 1995; Chu and Allegra 1996). It is unknown whether this regulation of translation also occurs in the T4 phage TS. The role of the TS on its own expression needs further investigation.

Figure 3.

Splicing of td mutants affecting the UAA stop codon at the 5′ site and the reading frame of exon 1. (A) The UAA stop codon, which immediately follows the 5′ splice site was mutated to UGA and UAG or readthrough (tdA771U). The amino acid sequence of the exon 1 product was modified via deletion of nucleotide −182 and insertion of a C at position −18, resulting in a product with 55 altered amino acids. (B) Splicing activity. The RNAs were isolated from E. coli cells containing no td gene (lane 1), the mutant tdC870U (lane 2), the wild type (lane 3) or the mutants described (lanes 5–9). The bands referring to mRNA, cryptic RNA and precursor are indicated by arrows. (C) P1 and cryptic P1. (P1) Sequences around the 5′ splice site (5′ ss) pair with intron sequences forming the P1 stem. Exon sequences are in uppercase, intron sequences in lowercase letters. The UAA stop codon following the 5′ ss is boxed. Positions altering this stop codon are indicated by arrows and the exchanged nucleotide is indicated. (Cryptic P1) An alternative folding of sequences surrounding the 5′ splice site is shown (Chandry and Belfort 1987). The original and the cryptic splice sites are indicated by arrows, as well as positions altered by mutations that stabilize the cryptic P1 folding. Negative numbers indicate distances to the 5′ splice site, positive numbers are intron positions.

Changing the natural UAA stop codon in P1 to UGA or UAG results in less efficient splicing

Like most group I introns in mRNAs, the td intron has a stop codon at its 5′ end that is in-frame with the exon. To test whether the nature of this stop codon (UAA) is essential or whether other stop codons could substitute, we changed the original UAA nonsense codon to UGA and UAG. The stop codon was also altered to a sense codon (UAU) by changing A-771 to U (Fig. 3, A and B, lane 8). Splicing activities were measured via a primer-extension assay and were quantitated by PhosphorImager measurements (Table 2). The stop codon in L1 just following the 5′ splice site is important, although not essential. In the construct that has the open reading frame into the intron, splicing is down to half of wild-type splicing. The ribosome probably disrupts the intron core structure, as the open reading frame reaches far into the core (P7.2). This confirms the observation made in the T4 nrdB intron, where the elimination of the stop codon also reduced splicing activity (Öhman-Heden et al. 1993).

Table 2.

Effects of different nonsense codons and deletion of the UAA stop codon at the 5‘ splice site and of altered protein sequence on splicing in vivo

| Mutation

|

Designation

|

Percent splicing

|

Percent cryptic RNA

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | wild type td | 41 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 0.7 |

| A770G | td A770G/UGA | 26.1 ± −3.3 | 10 ± −1.7 |

| A771G | td A771G/UAG | 29.4 ± −3.1 | 12.3 ± −2.6 |

| A771T | td A771U | 23.9 ± −1.7 | 3.6 ± −0.2 |

| ΔT587, Ins C751 | td 182Δ/−18Ins | 82.9 ± −3 | 23.3 ± −3.7 |

| C870T | td C870U | <1 | <1 |

Values for the spliced fraction of mRNA + cryptic RNA were determined as in Table 1.

Splicing is reduced in mutants with the UAG or UGA stop codons replacing the natural UAA stop codon in the intron. While mRNA splicing is significantly decreased, the amount of cryptic splice product is higher compared to the wild type (Fig. 3B, lanes 5, 6 and Table 2). The increase in cryptic splicing is likely attributable to stabilization of the cryptic P1 structure shown in Figure 3C. The altered A → G mutations at positions 770 and 771 enable G to base-pair with C at position −25. Total splicing, mRNA and cryptic RNA, in the UGA and UAG mutants is reduced to 2/3 of wild-type splicing activity.

Translation inhibitors efficiently inhibit splicing activity

To illuminate the necessity of translation for efficient splicing activity, we tested the effect of translation inhibitors on splicing in vivo. Chloramphenicol is known to block elongation of the translating ribosome and spectinomycin inhibits initiation. The td wild-type construct was grown to the exponential phase and incubated for 60 min with different concentrations (0, 8, 40, 80 and 123 μm) of the respective antibiotic. In Figure 4, lanes 1 and 6, shows splicing in the absence of antibiotic. With increasing amounts of the antibiotic chloramphenicol (lanes 2–5) and spectinomycin (lanes 7–10), splicing decreases dramatically. Both antibiotics are known to affect translation but do not affect splicing in vitro (von Ahsen et al. 1992). This demonstrates further the importance of translation for splicing.

Figure 4.

Splicing inhibition by translation inhibitors. Splicing activity was tested in the absence and in the presence of increasing amounts of the antibiotics chloramphenicol and spectinomycin. (Lanes 1, 6) In vivo isolated wild-type RNA grown without antibiotic. (Lanes 2–5, 7–10) RNA isolated from the strains grown in the presence of increasing amounts (8, 40, 80 and 123 μm) of chloramphenicol and spectinomycin, respectively. Bands are as indicated in Fig. 1.

A UGA–tRNA suppressor partially rescues splicing of the UGA stop codon mutant

To test whether readthrough of an exon stop codon can rescue splicing, a UGA suppressor tRNA was overexpressed in the KS-82 mutant, which contains a UGA codon in exon 1, 82 nucleotides upstream from the 5′ splice site. The su9 gene coding for a suppressor tRNAUGATrp (Kopelowitz et al. 1992) was cotransformed with the mutant KS-82, and splicing was compared to the KS-82 mutant strain and to the wild type both without the suppressor (Fig. 5A). The suppressor tRNA slightly rescues splicing. As a tRNA suppressor has to work with low efficiency, otherwise it would be deleterious to the cell, the gel was overexposed to detect very low splicing activity.

Figure 5.

A UGA suppressor tRNA partially rescues splicing in a UGA mutant. Mutant KS-82 was cotransformed with a compatible plasmid encoding a UGA supressor tRNA. (A) In vivo RNA was isolated from the KS -82 mutant alone and from the strain cotransformed with the supressor tRNA on a plasmid, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. As controls the extension products from the wild type and the splicing-deficient mutant (td C870U) are shown. (B) The strains (as indicated) were plated on a thymine–deficient medium to test the suppressor activity and the effect of S12 overexpression on translation. Thy− is thymine-deficient medium and Thy+ is a full medium.

The suppressor tRNA was also tested for its effect on synthesis of TS. The constructs, grown in the E. coli strain C600thy−, were tested for growth on thymine-deficient plates (Fig. 5B). The wild-type and the tRNA suppressor strains are the only ones able to grow on minimal medium. This result demonstrates that splicing and translation are rescued when the inserted stop codon is suppressed.

Overexpression of the ribosomal protein S12 slightly raises splicing activity in the stop codon mutants

Recently, it was demonstrated that cellular proteins enhance in vitro trans-splicing of the td intron. They were identified as ribosomal proteins with protein S12 being the most efficient (Coetzee et al. 1994). S12 was proposed to act as an RNA chaperone, which means that it might provide help in correctly folding the ribozyme or in unfolding trapped inactive structures. This protein does not bind specifically to the intron RNA, but rather nonspecifically, with a slight preference for exon sequences. Assuming that ribosomal protein S12 acts as an RNA chaperone in vivo, we probed for the role of the ribosome in splicing, by overexpressing S12. This might give us a first hint, whether splicing deficiency is attributable to misfolded or unfolded pre-RNA.

The strains of the wild-type td intron or the stop codon mutants were transformed with a plasmid overexpressing the ribosomal protein S12 (Fig. 6A) (Coetzee et al. 1994). In the wild-type construct, only a slight effect on splicing was observed, and the cryptic splice-site product (P + 8) was slightly decreased (Fig. 6, lanes 1,2), suggesting that S12 might destabilize the cryptic P1 stem shown in Figure 3C. This effect had been observed previously (T. Coetzee and M. Belfort, pers. comm.). S12 slightly raises splicing in all stop codon mutants by a factor of ∼2 (Table 3). The increase in splicing of mutant KS-82 was not quantifiable as splicing in the absence of overexpressed S12 was undetectable. From these results, we conclude that one possible explanation for the splicing deficiency in the stop codon mutants invokes folding problems of the pre-RNA.

Figure 6.

Splicing rescue by ribosomal protein S12 and by CYT-18. The td wild-type and the stop codon mutants were cotransformed with a compatible plasmid encoding ribosomal protein S12 (A) and CYT 18 (B). In vivo splicing activity was tested via the primer-extension assay. The extension products are labeled as in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Splicing increase of the stop codon mutants in the presence of overexpressed ribosomal protein S12

| Construct

|

x-Fold increase in splicing

|

|---|---|

| KS-223/+S12 | 2.1 |

| KS-27/+S12 | 1.4 |

| KS-82/+S12 | >2 |

| KS-5/G781U/+S12 | 2.3 |

| KS-15/+S12 | 1.6 |

The values indicate the increase of splicing of the stop codon mutants in the presence of overexpressed ribosomal protein S12 compared to splicing in the absence of overexpressed S12.

The mutant strains, with and without S12 overexpression, were tested for TS synthesis on thymine+ and thymine− selection plates (Fig. 5B). Overexpression of S12 has no effect on translation in the stop codon mutants, indicating that S12 does not act as a nonsense codon suppressor. S12 overexpression leads to an increase of splicing without affecting translation.

The tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase from N. crassa (CYT-18) efficiently rescues splicing of the stop codon mutants, but aberrant splicing products accumulate

As mentioned before, CYT-18 suppresses structural mutants of the td intron (Mohr et al. 1992) and stabilizes the three-dimensional structure of the intron RNA. To test whether folding of the intron was impaired in the stop codon mutants, CYT-18 was overexpressed together with the mutants, and in vivo splicing activity was tested (Fig. 6B). While CYT-18 has little effect on the wild-type activity, as observed previously (Mohr et al. 1992), splicing in the stop codon mutants was efficiently rescued. Rescue was efficient regardless of the position of the stop codon. However, splicing rescue by CYT-18 leads to an increase in aberrant products. Rescued splicing in the mutant KS-223, for example, results in P + 8, P + 9, and increased P + 12 in addition to P + 16 products (Fig. 6B, lane 2). Mutants KS-27, KS-15, and KS-5 produce less cryptic P + 8 product when rescued by CYT-18, consistent with the fact that the mutations destabilize the cryptic P1 stem (Figs. 6B, lanes 4,8,10, and Fig. 3C). These results are another indication, that in the absence of translation the pre-RNA is unable to fold into the splicing-competent structure.

Identification of an upstream sequence that interferes with splicing

When a stop codon is located 82 nucleotides upstream from the 5′ splice site, splicing activity is below 1% of wild type, while a stop codon located 27 nucleotides upstream allows a splicing activity of 10% (Table 1). This suggests that a sequence occurs between these two positions that negatively affects splicing. To narrow down and to identify such a sequence, two further mutants containing stop codons at positions −51 and −60 were constructed (Table 4). These two mutants spliced much better than KS-82. This result is indicative of a sequence between −60 and −80 that might interfere with folding of the intron, thereby inhibiting splicing. This idea is easily testable by altering the exon sequence in the −60/−80 region. We constructed a mutant with a stop codon at position −82 with an altered downstream sequence containing five point mutations spanning from position −79 to −64 in exon 1. In case this region undergoes base-pairing with intron sequences, it is expected that a potential long-range interaction would be disrupted by the point mutations. In the context of the five point mutations, the stop codon at position −82 should then no longer result in a totally splicing-deficient construct. Indeed, splicing activity of this multiple mutant was found to be 26% (Table 4). This result is a strong evidence in support of the idea that this region interferes with splicing by base-pairing with intron sequences.

Table 4.

Effect of stop codons and compensatory mutations in the −60/−80 region of exon 1 on splicing

| Mutation

|

Designation

|

Relative splicing activity (%)

|

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | wild-type td | 100 |

| C720A; G718T | KS-51 | 60 |

| G711A; T710G; G709T | KS-60 | 64 |

| T687A | KS-82 | <1 |

| T687A; T690C; C696T; T699C; G702A; T705C | KS-82/1 | 63 |

Values for the spliced fraction of mRNA were determined as in Table 1. Splicing activities relative to wild-type splicing are indicated.

We subsequently searched for intron sequences complementary to the −60/−80 region. We found a potential candidate located just upstream of the 3′ splice site. This potential interaction consists of 9 bp comprising nucleotides −81 to −73 of exon 1 and the terminal nucleotides of the intron (Fig. 7). This region is essential for the formation of the three dimensional structural elements P9.0a and P9.0b (Michel et al. 1989; Jaeger et al. 1993). Further experiments will be undertaken to verify this interaction, but compensatory mutations within the intron are problematic, as the splicing-competent structure must be maintained.

Figure 7.

Long-range interaction between exon 1 and the 3′ terminus of the intron. Potential base-pairing interaction between exon positions −81 to −73 and 3′-terminal sequences of the intron. Negative positions indicate distance to the 5′ splice site. Exon sequences are in uppercase, intron sequences in lowercase letters. (3′ ss) 3′ splice site. Mutations in mutant KS-82/1, which disrupt this pairing, are indicated. Underlined lowercase letters indicate intron positions involved in the three dimensional elements P9.0a and P9.0b (Jaeger et al. 1993; Michel et al. 1989).

Discussion

It is generally assumed that group I intron splicing is facilitated by RNA-binding proteins in vivo. A specific in vivo splicing factor for the td intron has not yet been found, and many attemps to isolate splicing-defective mutants in trans were unsuccessful (R. Schroeder and M. Belfort, unpubl.). However, it was shown that the StpA protein as well as the ribosomal protein S12 can enhance splicing in vitro (Coetzee et al. 1994; Zhang et al. 1995). Both proteins bind RNA nonspecifically, suggesting an RNA chaperone activity (Herschlag 1995).

Splicing was uncoupled from translation in the group I intron containing T4 phage-derived td gene by introducing nonsense codons in the upstream exon of the pre-mRNA. This resulted in severe splicing deficiency. The lack of spliced mRNA in the stop codon mutants is attributable neither due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay nor to the involvement of the translation product of exon 1 in splicing. A suppressor tRNAUGA partially rescues splicing in a UGA stop codon mutant. This is the first strong evidence that translation is required for efficient splicing in vivo. This evidence is further strengthened by the fact that translation inhibitors also lead to splicing deficiency. Many years ago, Schmelzer and Schweyen observed that chloramphenicol repressed splicing of yeast mitochondrial introns and suggested not only that mitochondrial proteins were necessary but that the translation machinery might interact more directly with intron maturation (Schmelzer and Schweyen 1982).

There are two possibilities for how the ribosome can promote splicing: (1) by resolving exon–intron interactions that interfere with intron folding and (2) by direct stabilization of the splicing competent structure. We present experimental evidence for the first function, and several observations suggest that the second mechanism cannot be ruled out.

To test whether the splicing defect in the stop codon mutants results from the inability of the pre-RNA to fold into the splicing competent structure, splicing rescue was tried with two proteins that are involved in RNA folding, the ribosomal protein S12 and CYT-18. S12 has been shown previously to activate trans-splicing of the td intron in vitro, interacting with exon sequences rather than with intron sequences (Coetzee et al. 1994). In its natural context, the ribosome, S12 has been implicated in tuning translational accuracy by modulating the dissociation constants of tRNAs in the P- and A-sites of the small ribosomal subunit (Powers and Noller 1994; Karimi and Ehrenberg 1996). Overexpression of S12 partially rescues splicing of the stop codon mutants. We assume that this S12 activity comes from S12 protein nonassociated to the ribosome. One possible role for S12 in splicing of pre-RNA introns might be the destabilization of exon structures that interfere with intron folding.

A stop codon positioned at −82 reduced splicing activity below 1%, whereas a nonsense codon positioned at −60 allows 60% of wild-type splicing. This phenomenon could be attributable to the existence of exon sequences between these positions that interfere with intron sequences. In excellent agreement with this idea, additional point mutations in the −82 stop codon mutant rescue splicing from below 1% to 63% relative splicing activity. This is a strong evidence, that the −82/−60 region interferes with splicing by undergoing base-pairing with intron sequences, disrupting the active intron conformation. In support of this idea, a sequence of 9 nucleotides, representing the 3′ terminus of the intron was found to be complementary to positions −81 to −73.

Thus it is very likely that the main function of the ribosome in splicing is to “iron out” exon sequences and to resolve potential exon–intron interactions, which prevent the intron from folding into the splicing competent structure. However, as stop codons even close to the 5′ splice site (at position −5 and −15) affect splicing, we think that the ribosome does more than just resolve exon structures. The ribosome might also stabilize the intron structure in a more specific way, like CYT-18 does. When CYT-18 is overexpressed in the mutants containing stop codons in exon 1, splicing is efficiently restored. Because CYT-18 helps to fold group I introns specifically, it is clear that the defect caused by the stop codons in exon 1 is a lack of correct folding. The ribosome might be able to recognize group I introns as they bear tRNA-like structural features (Caprara et al. 1996a,b). Preliminary binding assays with intron RNA to 70S ribosomes suggest that the ribosome can indeed bind the intron RNA with an affinity similar to mRNAs (K. Semrad and R. Schroeder, unpubl.). For further and profound studies, binding-assay conditions have to be established, which resemble the actual splicing situation: an occupied P-site of the ribosome and an mRNA, which ends at the P-site, such that binding of the intron to an mRNA-vacant A-site can be measured. The ability of ribosomes to bind molecules of that size is demonstrated by binding of the 10Sa (tm) RNA to E. coli ribosomes (Tu et al. 1995; Keiler et al. 1996). The 10Sa RNA has tRNA and mRNA properties, suggesting that the ribosome can accommodate a quite diverse set of RNAs. Another very strong evidence that ribosomes can bind correctly folded group I intron RNA, comes from the observation that the Tetrahymena intron reverse splices into 50S subunits and 70S ribosomes (Roman and Woodson 1995).

There are several indications that the ribosome has additional functions, which are unrelated to translation. Recently, it was shown that the ribosome is able to regulate the GTP-binding activity of a GTPase from the signal recognition particle (Bacher et al. 1996). Here, we present a first evidence for a novel type of ribosomal function: The ribosome seems to fine tune the folding of the intron RNA when splicing and translation are coupled.

Materials and methods

E. coli strains and growth media

E. coli strains used in this study were thymine-deficient derivatives of C600 strain [F−, supE44, thi-1, thr-1, leuB6, lacY1, tonA21, thy−]. Minimal media with and without thymine were as described (Belfort et al. 1983). For screening of the td phenotype, we used TBY-E + Thy and minimal medium. Bacto agar (1.5%) was added for solid media. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin (100 mg/liter), chloramphenicol (25 mg/liter), kanamycin (50 mg/liter), trimethoprim (25 mg/liter). Thymine was added at 50 mg/liter.

Plasmids

All td constructs are in context of the vector pTZ18U (U.S. Biochemical). The stop codon mutants in exon 1, the tdA770G/UGA and the tdA771G/UAG mutants, the frameshift mutant (td−182Δ/−18 Ins), and the tdΔintron mutants with and without stop codon KS-82 were derived from in vitro mutagenesis (Kunkel et al. 1987). The mutant tdC870U was described previously (Schroeder et al. 1991). The vector pA550 is a derivative of pACYC and carrying the trp tRNA synthetase from N. crassa (Mohr et al. 1992). The vector pWKS 130.S12 is a low-copy pACYC derivative and carries the ribosomal protein S12 under lac promoter (Coetzee et al. 1994; Wang and Kushner 1991). The su9 gene on the vector pJK 1, also compatible with the pTZ18U derivatives, codes for a suppressor tRNAUGATrp (Kopelowitz et al. 1992).

Oligonucleotides

A list of mutagenic oligonucleotides follows (mutagenic residues are underlined): KS-223; 5′-CCACTGTTTTCATTAAATTGGACC-3′;

KS-82; 5′-ATAGAACATATGTCAAGGCGGTAAT-3′; KS-60; 5′-AAATAGCCATTACGTCAATTAAACTGATAGA-3′; KS-51; 5′-CAAATCCAAATATCAATTACGCACATT-3′; KS-27; 5′-TCTACTGAGCGTCAATACCACTGCA-3′; KS-15; 5′-ACCCAAGAAAACTTATACTGAGCGTTG-3′;

KS-5/G781U; 5′-TCACCTTATACTAAGGCCTCAATTAACCCTAGAAAACATCTA-3′; td A770G/UGA; 5′-CTCAGGCCTCAATCAACCCAAGAAAAC-3′; td A771U/UAG; 5′-CTCAGGCCTCAACTAACCCAAGAAAAC-3′; td −182Δ; 5′-ATC AATAACTTCTΔTAATTTGGTCTAC-3′; td −18 Ins; 5′-AAGAAAACATCTACCTGAGCGTTGAT-3′; tdA771U; 5′-ACTCAGGCCTCAAATAACCCAAGAAAAC-3′; td Δintron; 5′-GACGCAATATTAAACGGTAGACCCAAGAAAACATCTACTG-3′; KS-82/1; 5′-GCCATTACGCACATTGAATTGGTAAAACATGTGTCAAGGCGGTAAT-3′. The oligo nucleotide for the primer-extension assay is NBS-2; 5′-GAGCAATATTAAACGGT-3′.

In vivo RNA isolation

For the isolation of cellular RNA the lysozyme freeze–thaw method was used as described (Belfort et al. 1990) with the following modifications: The cells were grown with IPTG added to a final concentration of 2 mm. For the extraction protocol the RNA was precipitated without addition of Mg(OAc)2 but with 1/100 volume of 0.5 m EDTA instead.

For the time curve of mRNA degradation (Fig. 2), rifampicin was added at an OD600 of 0.2 to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml and samples were taken from time points between 0 and 40 min. The following protocol was performed as described.

Primer extension reaction to determine splicing of td

The primer extension assay and was described previously (Mohr et al. 1992, see also Fig. 1B) with the following modifications: The reactions were annealed in a 90°C water bath for 1 min with 10 μg of total RNA (maximal volume of 2.5 μl), 1 ng 32P-labeled primer (1 μl) and 1 μl of hybridization buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.4, 60 mm KCl). The probes were allowed to cool to 45°C. For the extension reaction 2.2 μl of extension mix [1 μl H2O, 0.6 μl of extension buffer (500 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.4, 50 mm MgCl2, 50 mm DTT), 0.3 μl poisoned mix (6 μl 10 mm dCTP, 6 μl 10 mm dATP, 6 μl 10 mm dGTP, 25 μl 10 mm ddTTP) and 0.3 μl AMV reverse transcriptase (4U/μl)] were added. The reaction was incubated at 42°C for 45 min. After precipitation, formamide loading dye was added and half of the reaction was loaded on a 8% polyacrylamide gel (20 : 1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide, 7 m urea).

In vitro transcription

In vitro transcription was performed under suboptimal conditions to prevent hydrolysis of the transcripts: The td-containing plasmids were linearized with EcoRV. The transcriptions were performed in a total volume of 40 μl with 40 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 11 mm MgCl2, 2 mm spermidine, 10 mm NaCl, 2 μg linearized template, 2.5 mm ATP, GTP, UTP and 0.5 mm CTP, 30 μCi [35S] CTP, 25 mm DTT, 40 units of RNasin, and 20 units of T7 polymerase. The transcriptions were incubated over night at 4°C and then isolated from a 5% polyacrylamide gel (39 : 1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide, 7 m urea) and eluted over night in 400 μl elution buffer (250 mm Na acetate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris-HCl). After precipitation and resuspension, the transcripts were quantified in a scintillation counter.

In vitro splicing

In vitro transcripts (40 000 cpm) were incubated for 3 min at 56°C with splicing buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.3, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.4 mm spermidine) in a total volume of 10 μl. The assay was incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and then GTP was added to a final concentration of 10 μm. The reactions were performed at 37°C, stopped at different time points by the addition of stop solution (10 mm EDTA, 5 μg of tRNA) and precipitated. The reactions were resuspended in formamide dye and loaded on a 5% polyacrylamide gel (39 : 1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide, 7 m urea).

PhosphorImager quantification

For the quantifications of the primer-extension products, the program Image Quant was used. The percentage of splicing was calculated with the formula: mRNA + crypticRNA)x100/(preRNA + mRNA + crypticRNA. For mRNA splicing, the area of the mRNA product (P + 16 or P + 15 and P + 7, respectively) in addition with the reverse transcriptase stops at positions P + 12 and P + 13 were integrated plus the integrated area of cryptic splicing (P + 8) and compared to the integrated area of the preRNA (P + 5) by above mentioned formula. Values in Table 1 are from at least eight individual experiments, in Table 2 from at least two individual experiments, except for the mutant tdA771U, which was done only once.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hanna Engelberg-Kulka for the tRNA suppressor, Marlene Belfort for the S12 plasmid and Alan Lambowitz for the CYT-18 plasmid. We especially thank Elisabeth Clodi for her input into this work. We thank U. von Ahsen, C. Behrens, M. Belfort, P. Brion, T. Coetzee, B. Cousineau, M. Cusick, I. Hoch, R. Lease, M. Parker, B. Streicher, S. Wallace, H. Wank, D. Wittberger, and S. Woodson for critical comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF) grants nos. 9457 and 10615 to R.S.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL renee@gem.univievie.ac.at; FAX 43 1 798 6224.

References

- Bacher G, Luetcke H, Jungnickel B, Rapoport TA, Dobberstein B. Regulation by the ribosome of the GTPase of the signal-recognition particle during protein targeting. Nature. 1996;381:248–251. doi: 10.1038/381248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfort M, Moelleken A, Maley GF, Maley F. Purification and properties of T4 thymidylate synthase produced by the cloned gene in an amplification vector. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:2045–2051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfort M, Chandry PS, Pedersen-Lane J. Genetic delineation of functional components of the group I intron in the phage T4 td gene. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:181–192. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfort M, Ehrenman K, Chandry PS. Genetic and molecular analysis of RNA splicing in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1990;181:521–539. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)81149-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara MG, Lehnert V, Lambowitz AM, Westhof E. A tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase recognizes a conserved tRNA-like structural motif in the group I intron catalytic core. Cell. 1996a;87:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara MG, Mohr G, Lambowitz AM. A tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase protein induces tertiary folding of the group I intron catalytic core. J Mol Biol. 1996b;257:512–531. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreras CW, Santi D. The catalytic mechanism and structure of thymidylate synthase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:721–762. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech TR. Self-splicing group I introns. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:543–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.002551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech TR, Damberger SH, Gutell R. Representation of the secondary and tertiary structure of group I introns. Nature Struct Biol. 1994;1:273–280. doi: 10.1038/nsb0594-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandry PS, Belfort M. Acitvation of a cryptic 5′ splice site in the upstream exon of the phage T4 td transcript: Exon context, missplicing, and mRNA deletion in a fidelity mutant. Genes & Dev. 1987;1:1028–1037. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.9.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu E, Allegra CJ. The role of thymidylate synthase as an RNA binding protein. BioEssays. 1996;18:191–198. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu E, Voeller D, Koeller DM, Drake JC, Takimoto CH, Maley GF, Maley F, Allegra C. Identification of an RNA binding site for human thymidylate synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:517–521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee T, Herschlag D, Belfort M. Escherichia coli proteins, including ribosomal protein S12, facilitate in vitro splicing of phage T4 introns by acting as RNA chaperones. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:1575–1588. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gampel A, Nishikimi M, Tzagoloff A. CBP2 protein promotes in vitro excision of a yeast mitochondrial group I intron. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5424–5433. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gott J M, Zeeh A, Bell-Pederson D, Ehrenman K, Belfort M, Shub DA. Genes within genes: Independent expression of phage T4 intron open reading frames and the genes in which they reside. Genes & Dev. 1988;2:1791–1799. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12b.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschlag D. RNA chaperones and the RNA folding problem. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20871–20874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschlag D, Khosla M, Tsuchihashi Z, Karpel RL. An RNA chaperone activity of non-specific RNA binding proteins in hammerhead ribozyme catalysis. EMBO J. 1994;13:2913–2924. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger L, Westhof E, Michel F. Monitoring of the cooperative unfolding of the sunY group I intron of bacteriophage T4. The active form of the sunY ribozyme is stabilized by multiple interactions with 3′ terminal intron components. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:331–346. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi RZ, Ehrenberg M. Dissociation rates of peptidyl-tRNA from the P-site of E. coli ribosomes. EMBO J. 1996;15:1149–1154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiler KC, Waller PRH, Sauer RT. Role of a peptide tagging system in degradation of proteins synthesized from damaged messenger RNA. Science. 1996;271:990–993. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowitz J, Hampe C, Goldman R, Reches M, Engelberg-Kulka H. Influence of codon context on UGA suppression and readthrough. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:261–269. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90920-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel TA, Roberts JD, Zakour RA. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotype selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambowitz AM, Belfort M. Introns as mobile genetic elements. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:587–622. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambowitz AM, Perlman PS. Involvement of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and other proteins in group I and group II intron splicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:440–444. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90283-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazowska JC, Jacq C, Slonimski PP. Sequence of introns and flanking exons in wild-type and box3 mutants of cytochrom b reveals an interlaced splicing protein coded by an intron. Cell. 1980;22:333–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel F, Westhof E. Modelling of the three-dimensional architecture of group I catalytic introns based on comparative sequence analysis. J Mol Biol. 1990;216:585–610. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90386-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel F, Hanna M, Green R, Bartel DP, Szostak JW. The guanosine binding site of the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Nature. 1989;342:391–395. doi: 10.1038/342391a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr G, Zhang A, Gianelos JA, Belfort M, Lambowitz AM. The Neurospora CYT-18 protein suppresses defects in the Phage T4 td intron by stabilizing the catalytically active structure of the intron core. Cell. 1992;69:483–494. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90449-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr G, Caprara MG, Guo Q, Lambowitz AM. A tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase can function similarly to an RNA structure in the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Nature. 1994;370:147–150. doi: 10.1038/370147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy FL, Cech TR. An independently folding domain of RNA tertiary structure within the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5291–5300. doi: 10.1021/bi00071a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson G, Belasco JG, Cohen SN, von Gabain A. Effects of premature termination of translation on mRNA stability depends on the site of ribosome release. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:4890–4894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman-Heden M, Ahgren-Stalhandske A, Hahne S, Sjöberg BM. Translation across the 5′-splice site interferes with autocatalytic splicing. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:975–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers T, Noller HF. Selective perturbation of G530 of 16 S rRNA by translational miscoding agents and a streptomycin-dependence mutation in protein S12. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:156–172. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman J, Woodson SA. Reverse splicing of the Tetrahymena IVS: Evidence for multiple reaction sites in the 23S rRNA. RNA. 1995;1:478–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer C, Schweyen RJ. Evidence for ribosomes involved in splicing of yeast mitochondrial transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:513–524. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.2.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder R, von Ahsen U, Belfort M. Effects of mutations of the bulged nucleotide in the conserved P7 pairing element of the phage T4 td intron on ribozyme function. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3295–3303. doi: 10.1021/bi00227a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchihashi Z, Khosla M, Herschlag D. Protein enhancement of hammerhead ribozyme catalysis. Science. 1993;262:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.7692597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu GF, Reid GE, Zhang JG, Moritz RL, Simpson RJ. C-terminal extension of truncated recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli with a 10Sa RNA decapeptide. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9322–9326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voeller DM, Changchien L-M, Maley G, Maley F, Takechi T, Turner REWM, Allegra CJ, Chu E. Characterization of a specific interaction between Escherichia coli thymidylate synthase and Escherichia coli thymidylate synthase mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;25:869–875. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.5.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Ahsen U, Davies J, Schroeder R. Antibiotic inhibition of group I ribozyme function. Nature. 1991;353:368–370. doi: 10.1038/353368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Non-competitive inhibition of group I intron RNA self-splicing by aminoglycoside antibiotics. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:935–941. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91043-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walstrum SA, Uhlenbeck OC. The self-splicing RNA of Tetrahymena is trapped in a less active conformation by gel purification. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10573–10576. doi: 10.1021/bi00498a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RF, Kushner SR. Construction of versatile low-copy number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring RB, Towner P, Minter SJ, Davies RW. Splice-site selection by a self-splicing RNA of Tetrahymena. Nature. 1986;321:133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks KM, Cech TR. Efficient protein-facilitated splicing of the yeast mitochondrial bI5 intron. Biochemistry. 1995a;34:7728–7738. doi: 10.1021/bi00023a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Protein facilitation of group I splicing by assembly of the catalytic core and the 5′ splice site domain. Cell. 1995b;82:221–230. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodson SA. Exon sequences distant from the splice junction are required for efficient self-splicing of the Tetrahymena IVS. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4027–4032. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.15.4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodson SA, Cech TR. Alternative secondary structures in the 5′ exon affect both forward and reverse self-splicing of the Tetrahymena intervening sequence RNA. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2042–2050. doi: 10.1021/bi00222a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodson SA, Emerick VL. An alternative helix in the 26S rRNA promotes excision and integration of the Tetrahymena intervening sequence. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1137–1145. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaug AJ, McEvoy MM, Cech TR. Self-splicing of the group I intron from Anabaena pre-tRNA: Requirement for base-pairing of the exons in the anticodon stem. Biochemistry. 1993;32:7946–7953. doi: 10.1021/bi00082a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A, Derbyshire V, Galloway Salvo JL, Belfort M. Escherichia coli protein StpA stimulates self-splicing by promoting RNA assembly in vitro. RNA. 1995;1:783–793. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]