Abstract

Rifaximin is a rifampicin derivative, poorly absorbed by the gastro-intestinal tract. We studied the in vitro susceptibility to rifamixin of 1082 Clostridium difficile isolates; among these,184 isolates from a strain collection were tested by an in-house rifaximin disc (40 µg) diffusion test, by an in-house rifaximin broth microdilution test, by rifampicin Etest and by rpoB gene sequencing. In the absence of respective CLSI or EUCAST MIC breakpoints for rifaximin and rifampicin against C. difficile we chose MIC ≥32 µg ml−1 as criterion for reduced in vitro susceptibility. To further validate the disc diffusion test 898 consecutive clinical isolates were analysed using the disc diffusion test, the Etest and rpoB gene sequence analysis for all resistant strains. Rifaximin broth microdilution tests of the 184 reference strains yielded rifaximin MICs ranging from 0.001 (n = 1) to ≥1024 µg ml−1 (n = 61); 62 isolates showed a reduced susceptibility (MIC ≥32 µg ml−1). All of these 62 strains showed rpoB gene mutations producing amino acid substitutions; the rifampicin- and rifaximin-susceptible strains showed either a wild-type sequence or silent amino acid substitutions (19 strains). For 11 arbitrarily chosen isolates with rifaximin MICs of >1024 µg ml−1, rifaximin end-point MICs were determined by broth dilution: 4096 µg ml−1 (n = 2), 8192 µg ml−1 (n = 6), 16 384 µg ml−1 (n = 2) and 32 678 µg ml−1 (n = 1). Rifampicin Etests on the 184 C. difficile reference strains yielded MICs ranging from ≤0.002 (n = 117) to ≥32 µg ml−1 (n = 59). Using a 38 mm inhibition zone as breakpoint for reduced susceptibility the use of rifaximin disc diffusion yielded 59 results correlating with those obtained by use of rifaximin broth microdilution in 98.4 % of the 184 strains tested. Rifampicin Etests performed on the 898 clinical isolates revealed that 67 isolates had MICs of ≥32 µg ml−1. There were no discordant results observed among these isolates with reduced susceptibility using an MIC of ≥32 µg ml−1 as breakpoint for reduced rifampicin susceptibility and a <38 mm inhibition zone as breakpoint for reduced rifaximin susceptibility. The prevalence of reduced susceptibility was 7.5 % for all isolates tested. However, for PCR ribotype 027 the prevalence of reduced susceptibility was 26 %. Susceptibility testing in the microbiology laboratory therefore could have an impact on the care and outcome of patients with infection. Our results show that rifaximin – despite its water-insolubility – may be a suitable candidate for disc diffusion testing.

Introduction

Clostridium difficile is a spore-forming Gram-positive anaerobic bacterium and a major cause of nosocomial and community-acquired diarrhoea (Wiström et al., 2001). Metronidazole and oral vancomycin are the main antibiotics used to treat C. difficile infection (CDI). In 2005, in Austria, oral rifaximin was licensed for ‘treatment of gastrointestinal diseases caused or partially caused by rifaximin-susceptible bacteria, e.g. gastrointestinal infections, pseudomembranous colitis due to C. difficile, hepatic encephalopathy, small bowel bacterial overgrowth and diverticulitis’ (Willerroider, 2009). However, to our knowledge, no guidelines have yet been published to test in vitro susceptibility of C. difficile to rifaximin. Two study groups previously used ≥32 mg l−1 (O’Connor et al., 2008; Jiang et al., 2010) as breakpoint for resistance using agar dilution testing, a method not widely employed in routine testing of clinical isolates. Jiang et al. (2000) reported high rifaximin concentrations (4000 to 8000 µg g−1) in stools 3 days after a single oral administration. Johnson et al. (2007) reported on the possible prevention of recurrence of CDI by administering rifaximin immediately after completion of the last course of vancomycin therapy of CDI.

In Austria, rifaximin is widely used to treat CDI, and microbiological laboratories often receive requests for in vitro susceptibility testing of clinical C. difficile isolates against this substance. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the disc diffusion method can be applied to test in vitro susceptibility of C. difficile to rifaximin.

Methods

Micro-organisms.

One hundred and eighty-four C. difficile isolates were obtained from the reference strain collection of the Austrian national C. difficile reference centre, including ATCC strain 9689, and 50 strains previously provided by Leeds University Hospital (UK), 3 strains from the Public Health Laboratory Maribor (Slovenia) and 24 strains from Leiden University Hospital (Netherlands). In addition, 898 non-duplicate clinical isolates were tested, cultured in 21 Austrian medical laboratories in 2009.

All 1082 isolates were stored at −80 °C in cryobank tubes (Mast Diagnostics) until testing. Isolates were recultivated on Columbia blood agar plates (bioMérieux); all were tested for PCR ribotype (RT) (Indra et al., 2008), toxin A (A) (van den Berg et al., 2004), toxin B (B) (Kato et al., 1991, 1999), binary toxin (BT) (Stubbs et al., 2000) and tcdC deletion (Spigaglia & Mastrantonio, 2002). Tables 1 and 2 list the PCR ribotypes of these isolates. All 1082 isolates except one (PCR ribotype 010) produced at least toxin B; 149 of them (14 %) were A/B/BT positive and belonged to the following ribotypes: 027 (n = 99), 078 (n = 10), 176 (n = 9), 023 (n = 5), 080 (n = 3), 126 (n = 2), 419 (n = 2), 045 (n = 2), 411 (n = 2), 429 (n = 2), 250 (n = 1), 413 (n = 1), 018 (n = 1), 515 (n = 1), 344 (n = 1), 605 (n = 1), 606 (n = 1), 616 (n = 1), 654 (n = 1), 655 (n = 1), 656 (n = 1), 657 (n = 1), 658 (n = 1). If possible nomenclature was used according to that given by the John Brazier’s laboratory, due to the higher quality of resolution gained with capillary sequencer-based PCR-ribotyping (Indra et al., 2008) strains not assigned by John Brazier’s laboratory were given numbers starting with 400.

Table 1. Distribution of ribotypes among 184 C. difficile isolates from the strain collection of the Austrian national C. difficile reference centre .

| Ribotype | No. of strains | Percentage |

| 027 | 26 | 14.13 |

| 053 | 16 | 8.70 |

| 001 | 7 | 3.80 |

| 014/0 | 6 | 3.26 |

| 005 | 3 | 1.63 |

| 056 | 3 | 1.63 |

| 078 | 3 | 1.63 |

| 239 | 3 | 1.63 |

| 408 | 3 | 1.63 |

| 002/2 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 012 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 017 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 020 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 029 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 031 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 043 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 046 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 404 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 503 | 2 | 1.09 |

| 510 | 2 | 1.09 |

| Other* | 92 | 50 |

Represented by one isolate each: 002/0, 002/1, 003, 004, 006, 007, 009, 010, 014, 015, 016, 018, 019, 023, 025, 026, 033, 035, 036, 037, 039, 040, 042, 045, 047, 049, 050, 051, 052, 054, 055, 057, 058, 060, 062, 063, 064, 066, 067, 068, 070, 072, 075, 076, 077, 079, 080, 081, 083, 084, 085, 087, 094, 095, 106, 115, 117, 118, 122, 126, 131, 153, 169, 174, 201, 209, 212, 220, 411, 413, 434, 441, 444, 448, 466, 497, 504, 523, 524, 539, 542, 548, 622, 627, 633, 643, 649, 650, 651, 652, 653, 654.

Table 2. Distribution of ribotypes among 898 clinical C. difficile isolates from 2009.

| Ribotype | No. of strains | Percentage |

| 053 | 198 | 22 |

| 014/0 | 81 | 9.0 |

| 027 | 73 | 8.1 |

| 002/2 | 35 | 4.0 |

| 001 | 28 | 3.1 |

| 005 | 26 | 2.8 |

| ‘Infrequent’ ribotypes (n = 10–25)* | 161 | 17.8 |

| ‘Rare’ ribotypes (n = <10)† | 296 | 33.2 |

010, 012, 018, 020, 029, 078, 241, 408, 600.

003, 009, 014/5, 015, 017, 019, 023, 025, 026, 031, 043, 045, 046, 049, 054, 056, 066, 070, 080, 081, 087, 126, 153, 176, 203, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 211, 212, 220, 232, 236, 237, 239, 250, 403, 404, 405, 411, 413, 415, 419, 425, 429, 430, 431, 432, 434, 438, 439, 440, 441, 442, 448, 449, 451, 453, 457, 470, 472, 477, 481, 483, 484, 486, 492, 495, 496, 498, 499, 500, 501, 502, 503, 504, 505, 507, 508, 510, 512, 514, 515, 516, 518, 519, 520, 523, 525, 526, 530, 531, 532, 535, 537, 542, 548, 549, 601, 602, 603, 604, 605, 606, 607, 608, 609, 610, 611, 612, 613, 614, 615, 616, 617, 618, 619, 620, 621, 622, 623, 624, 625, 626, 627, 628, 629, 630, 631, 632, 633, 634, 635, 636, 637, 638, 639, 640, 641, 642, 643, 644, 645, 646, 647, 648, 655, 656, 657, 658.

Antimicrobial agents and susceptibility testing.

The 184 isolates from the strain collection were tested by an in-house rifaximin disc (40 µg) diffusion test (Oxoid; custom-made product), by an in-house rifaximin broth microdilution test and by rifampicin Epsilon-test (Etest) (bioMérieux). The 898 clinical isolates from 2009 were tested only by disc diffusion test and rifampicin Etest (bioMérieux). Rifaximin discs were custom-made (Oxoid) by Gebro Pharma. The disc diffusion tests were performed on Brucella blood agar plates supplemented with 5 mg haemin l−1 and 1 mg vitamin K l−1 (Oxoid).

The rifaximin broth microdilution test was performed as follows. Rifaximin was purchased as a powder from Alfa Wassermann. Sterile stock solutions were prepared according to the instructions of CLSI for testing of anaerobes (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2007). In short, rifaximin was dissolved in methanol and then diluted in 0.9 % saline solution. Serial twofold dilutions in ATB S-medium containing menadione (vitamin K3) at 0.5 mg l−1 and haemin at 15 mg l−1 (bioMérieux) were prepared for rifaximin concentrations covering a range from 0.000125 to 1024 µg ml−1; 96-well microdilution plates were filled with ATB S-medium (bioMérieux) containing the respective antibiotic concentrations. The antibiotic stocks were freshly prepared on the day of testing. For inoculum preparation, test organisms were cultured for 48 h anaerobically on Columbia blood agar plates (bioMérieux) at 37 °C; bacteria were suspended in 0.9 % saline solution to yield McFarland 0.5 and diluted 1 : 10 into the medium, so that the final test concentration of bacteria was approximately 1×106 c.f.u. ml−1. Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration at which no growth was observed after incubation for 48 h at 37 °C in an anaerobic atmosphere using anaerobic jars and GasPak (BD). Growth controls were performed by inoculation of antibiotic-free medium with an aliquot of the primary inoculum at a concentration of 105 c.f.u. per well; purity testing was performed by transferring an aliquot of 10 µl onto two Columbia blood agar plates with incubation under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, respectively.

Rifampicin Etests (MIC range 0.002–32 µg ml−1) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (bioMérieux) using Brucella blood agar plates supplemented with haemin (5 mg l−1) and vitamin K (1 mg l−1) (Oxoid).

In the absence of respective CLSI or EUCAST MIC breakpoints for rifaximin and rifampicin against C. difficile we chose MIC ≥32 µg ml−1 as criterion for reduced in vitro susceptibility, as suggested by O’Connor et al. (2008) and Jiang et al. (2010). Setting of zone diameter breakpoints for rifaximin susceptibility testing by disc (40 µg) diffusion was performed according to the recommendations of Turnidge & Paterson (2007).

Statistical analyses were performed with stata/ic 10.1 (StataCorp).

Detection of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the rpoB gene.

DNA was extracted from cultures using the MagNA Pure Compact (Roche Diagnostics) according to the producer’s manual to a final volume of 50 µl. Primers RifFOR (5′-CAAGATATGGAAGCTATAAC-3′) and RifREVlang (5′-GTGATTCTATAAATCCAAATTC-3′) were used in PCRs containing 25 µl HotStar Taq Master Mix (Qiagen), 5 µl (5 pmol µl−1) of each primer, 13 µl water and 2 µl DNA. Amplification was performed in a PCR thermocycler (15 min 96 °C, 30 cycles of 1 min 94 °C, 1 min 52 °C and 1 min 72 °C, and finally 10 min 72 °C). PCR products were cleaned up with Escherichia coli exonuclease I, and shrimp alkaline phosphatase (Fermentas) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing PCR containing 2 µl Big-Dye-Mix (Applied Biosystems), 1 µl Sequencing Buffer (Applied Biosystems) 4 µl water, 1 µl RifFOR or RifREVlang primer (10 pmol−1) and 2 µl DNA was performed in a commercial PCR thermocycler (1 min 96 °C, 30 cycles of 20 s 96 °C, 20 s 50 °C and 4 min 60 °C). The amplified products were cleaned up with Centri Sep 96-well plates or Centri Sep 8 well strips (Applied Biosystems) for dye terminator clean-up according to the manufacturer’s manual. Samples were analysed in an ABI 3130 genetic analyser (Applied Biosystems) with 36 cm capillary loaded with a POP7 gel (Applied Biosystems).

Sequences were analysed for the presence of SNPs within the rpoB gene using Kodon (Applied Maths) version 3.5 by aligning the samples to the rpoB gene sequence of a reference wild-type C. difficile strain (CD630; NC_009089) downloaded from the NCBI database.

Results

Results for reference strains

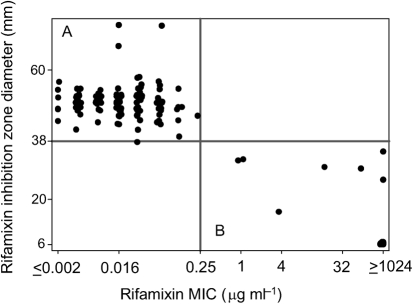

Rifaximin disc (40 µg) diffusion testing of the 184 reference strains yielded inhibition zone diameters ranging from 6 mm to 74 mm. Rifaximin broth microdilution tests of the 184 reference strains yielded rifaximin MICs ranging from 0.001 (n = 1) to ≥1024 µg ml−1 (n = 61); 62 strains showed reduced susceptibility with an MIC of at least 32 µg ml−1. The MIC50 of rifaximin was 0.032 µg ml−1 and the MIC90 was ≥1024 µg ml−1; the inhibition diameters in comparison to the results obtained by broth microdilution test are summarized in Fig. 1. The most common rpoB mutation found within this group was R505K (n = 46); other mutations were H502N+R505K (n = 6), H502Y (n = 2), H502N (n = 2) and one each of H502L, H502N+A555A, L487F+H502Y, R505K+I548M, D492V and S550F.

Fig. 1.

Rifaximin disc (40 µg) diffusion test results of 184 C. difficile reference strains compared to MICs obtained by the rifaximin broth microdilution test. All measured ‘sensitive’ C. difficile strains (n = 122) are grouped in quadrant A, in contrast to the 62 strains identified as ‘reduced susceptibility’ in quadrant B.

For 11 arbitrarily chosen strains with rifaximin MICs of >1024 µg ml−1, rifaximin end-point MICs were determined by broth dilution: 4096 µg ml−1 (n = 2: strains 2228 and 2639), 8192 µg ml−1 (n = 6: strains 2236, 2285, 2312, 2383, 2816 and 3025), 16 384 µg ml−1 (n = 2: strains 3091 and 910016) and 32 678 µg ml−1 (n = 1: strain 3098). These 11 strains yielded the following mutations in their rpoB genes: R505K (strains 2228, 2236, 2285, 2312, 2383, 2639, 3091 and 910016), L487F+H502Y (strain 2816), H502N+R505K (strain 3025), R505K+I548M (strain 3098).

Rifampicin Etests on these 184 C. difficile strains yielded MICs ranging from ≤0.002 (n = 117) to ≥32 µg ml−1 (n = 59); 59 strains had reduced susceptibility (MIC ≥32 µg ml−1). The MIC50 of rifampicin was ≤0.002 µg ml−1 and the MIC90 was ≥32 µg ml−1; all 59 strains showed mutations in the rpoB region (R505K (n = 46), H502N+R505K (n = 6), H502Y (n = 2) and one each of H502L, S550F, H502N+A555A, L487F+H502Y, R505K+I548M). In 181 (98.4 %) of the 184 strains tested, the use of the rifampicin Etest yielded results (reduced susceptibility or non-resistant) in accordance with those obtained by the rifaximin broth microdilution test. Discordant results (rifaximin vs rifampicin) were found for three strains. Strain 2347/655 (showing an H502N rpoB mutation) and 3153/PCR ribotype 002/0 (showing a D492V rpoB mutation) had a rifaximin broth microdilution MIC of ≥1024 µg ml−1 and a rifampicin Etest MIC of 0.064 µg ml−1 and 1 µg ml−1, respectively. Strain Lee047/PCR ribotype 047 had a rifaximin broth microdilution MIC of 64 µg ml−1 and a rifampicin Etest MIC of 0.25 µg ml−1. Molecular analyses of these strains revealed a mutation in the rpoB gene giving an H502N amino acid substitution (Table 3).

Table 3. Amino acid substitutions detected by rpoB sequence analysis in C. difficile strains with discordant results.

| Isolate ID no. | rpoB mutation* | Rifampicin MIC (µg ml−1) | Rifaximin MIC (µg ml−1) | Rifaximin DD† inhibition zone (mm) |

| 2203 | H502N | 0.5 | 1 | 32 |

| 2347 | H502N | 0.064 | ≥1024 | 34 |

| 2663 | D492N | 0.064 | 1 | 36 |

| 3018 | S550Y | 0.016 | 1 | 32 |

| 3109 | T501T, L506L, G510G, G512G, F521F, E541E, K556K | 0.125 | 16 | 30 |

| 3141 | S475S, F481F, D492D, T501T, A508A, G510G, T539T, K556K | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| 3153 | D492V | 1 | ≥1024 | 26 |

| Lee047 | H502N | 0.25 | 64 | 30 |

Resulting amino acid substitution shown.

DD, disc diffusion.

Using an inhibition zone of <38 mm as breakpoint for reduced susceptibility, the use of rifaximin disc diffusion yielded results correlating with those received by the use of rifaximin broth microdilution in 180 (97.8 %) of the 184 strains tested. Strain 2203/PCR ribotype 053 and 3018/PCR ribotype 018 had rifaximin inhibition zones of 32 mm and rifaximin broth microdilution MICs of 1 µg ml−1 and showed an H502N or S550Y rpoB gene mutation, respectively. Strain 3109/PCR ribotype 002/0 had a rifaximin inhibition zone of 30 mm and a rifaximin broth microdilution MIC of 16 µg ml−1 and showed a number of silent mutations (T501T, L506L, G510G, G512G, F521F, E541E, K556K) in the rpoB gene. Strain 3141/PCR ribotype 539 had a rifaximin inhibition zone of 16 mm and a rifaximin broth microdilution MIC of 4 µg ml−1, and also showed a number of silent mutations (S475S, F481F, D492D, T501T, A508A, G510G, T539T, K556K) (Table 3).

The 58 strains with reduced susceptibility to rifampicin and rifaximin showed rpoB gene amino acid substitutions as follows: R505K (n = 46), H502N+R505K (n = 5), H502Y (n = 2) and one each of H502L, S550F, H502N+A555A, L487F+H502Y and R505K+I548M.

Of the 117 rifampicin- and rifaximin-susceptible strains with MICs of ≤0.002 µg ml−1, 98 (84 %) showed no point mutations in rpoB; 19 showed only silent amino acid substitutions as follows: T501T+L506L+G510G+G512G+F521F+E541E+K556K (n = 11), A555A (n = 6), L500L (n = 2).

Correlation of rifampicin MICs obtained by broth dilution with rifaximin disc diameters was tested by Kendall’s tau-b correlation coefficient: −0.42 (P<0.001 for the hypothesis that both parameters were independent).

Results for clinical isolates

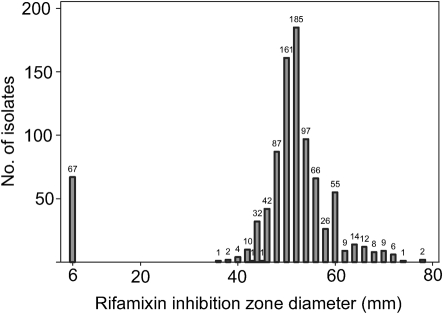

Rifaximin disc (40 µg) diffusion testing performed on 898 clinical C. difficile isolates yielded inhibition zone diameters ranging from 6 mm (n = 67) to 78 mm (n = 2) (Fig. 2). Using an inhibition zone <38 mm as breakpoint for reduced susceptibility a total of 68 strains with reduced susceptibility were identified.

Fig. 2.

Rifaximin disc (40 µg) diffusion testing performed on 898 clinical C. difficile isolates yielding inhibition zone diameters ranging from 6 mm (zero inhibition) to 78 mm.

Rifampicin Etests performed on the 898 isolates revealed that 67 isolates had MICs of ≥32 µg ml−1 for rifampicin and that 819 had MICs of ≤0.002 µg ml−1; 12 isolates (1.3 %) exhibited rifampicin MICs between these extremes. By rifaximin disc diffusion test, the 67 strains with reduced rifampicin susceptibility exhibited no inhibition zone. No discordant results were observed among these 67 isolates with reduced susceptibility using an MIC of ≥32 µg ml−1 as breakpoint for reduced rifampicin susceptibility and a <38 mm inhibition zone as breakpoint for reduced rifaximin susceptibility. Isolate 2663/PCR ribotype 053 had a rifampicin Etest MIC of 0.064 µg ml−1 and a rifaximin inhibition zone of 36 mm; molecular analyses revealed a D492N mutation in the rpoB gene (Table 3).

Discussion

All the rifamycins are semisynthetic derivatives of rifamycin B, a fermentation product of Amycolatopsis mediterranei, formerly named Streptomyces mediterranei. Rifamycin B exerts poor antimicrobial activity, but is easily produced and readily converted chemically into rifamycin S, from which most active derivatives are prepared (Parenti & Lancini, 2003). Rifaximin is a semi-synthetic derivative of rifamycin S formulated for oral administration. In the 1980s it was only available in Italy, but today it is marketed worldwide mainly for the treatment of gastrointestinal infections and the treatment of chronic hepatic encephalopathy (Corazza et al., 1988; Festi et al., 1992). Jiang et al. (2000) reported high rifaximin concentrations (4000 to 8000 µg g−1) in stools 3 days after single oral administration.

Although adequate antimicrobial drug concentrations should be achieved by the high dosage of the non-absorbable rifaximin, the constraints imposed by possible drug resistance (O’Connor et al., 2008) often impel clinicians to request in vitro susceptibility testing of C. difficile isolates from patients not responding to therapy. Our results on 11 arbitrarily chosen isolates from the group with reduced susceptibility to rifaximin (MIC >1024 µg ml−1) showed MICs ranging from 4096 to 32 678 µg ml−1, so that a breakpoint for resistance between >32 µg ml−1 and 1024 µg ml−1 can be considered for the future.

We evaluated a rifaximin disc diffusion test and found it substantially equivalent to an in-house rifaximin broth microdilution test. The level of performance considered acceptable for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance in premarket notification of commercial antimicrobial susceptibility systems is (among others) >89.9 % categorical agreement (same susceptible, intermediate or resistant classification), ≤1.5 % very major errors (false susceptibility based on the number of resistant organisms) and ≤3 % major errors (false resistance based on the number of susceptible isolates) (Richter & Ferraro, 2007). Accepting an MIC ≥32 µg ml−1 as criterion for reduced rifaximin susceptibility, a rifaximin inhibition zone of <38 mm would represent a valid resistance breakpoint in the 40 µg disc diffusion test described here.

We also found good correlation between the rifaximin and rifampicin susceptibility testing results. The number of discordant results (n = 8) concerning supposed resistance based on the rifampicin Etest and rifaximin disc diffusion test on C. difficile isolates could be seen as an argument to introduce the criterion ‘intermediate’ for rifampicin susceptibility testing. If we take the EUCAST breakpoints for staphylococci (S≤0.06/R>0.5 µg ml−1) for the rifampicin Etest, the correlation would increase to 99.45 % (five discordant results) (EUCAST, 2010). Our suggestions for preliminary breakpoints between susceptible, indeterminate and resistant are summarized in Table 4 for the Etest and the broth microdilution method to be validated in future studies. In our opinion no reliable intermediate breakpoint result can be given for the disc test; however, all isolates in question showed rpoB mutations yielding an amino acid change.

Table 4. Suggested preliminary breakpoints.

| Rifaximin DD* inhibition zone (mm) | Rifaximin MIC (µg ml−1) | Rifampicin MIC (µg ml−1) | |

| Susceptible | ≥38 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.06 |

| Intermediate | – | 0.5–16 | 0.012–16 |

| Resistant | <38 | ≥32 | ≥32 |

DD, disc diffusion.

Rifamycin resistance is commonly the result of a mutation that alters the β-subunit of RNA polymerase, reducing its binding affinity for rifamycins (Struelens, 2003). This study found rpoB mutations in all of the 62 strains showing reduced susceptibility with the rifaximin broth microdilution test. Interestingly, only H502N and D492V mutations showed discordant results between the rifampicin Etest and the rifaximin broth microdilution test in the 184 strains analysed, indicating a potential connection between mutation in the rpoB region and the efficacy of the antibiotic used. Future studies would enable examination of this potential connection.

Our molecular investigations confirmed mutations resulting in amino acid substitutions in RpoB for all eight isolates with discordant results with reduced susceptibility to rifaximin and rifampicin. Interestingly, two strains showing seven or eight silent mutations also showed reduced susceptibility with the disc diffusion test, but not with any of the other methods tested. Since no other mutation could be found in the rpoB gene a mutation in another gene influencing the activity of rifaximin has to be taken into consideration. Studying in vitro activity of rifaximin against C. difficile, Ripa et al. (1987) previously postulated the occurrence of chromosomal resistance against rifaximin caused by mutation. In agreement with these authors, we found a good correlation between rifaximin and rifampicin susceptibility testing in vitro, underpinning the data obtained by O’Connor et al. (2008). However, these results seem to be in contrast to the findings of Jiang et al. (2010), who could not predict rifaximin resistance by doing only rifampicin resistance testing. Comparison of our data and those of O’Connor et al. (2008) with the study by Jiang et al. (2010) suggests that the use of acetone as solvent for rifaximin and rifampicin by Jiang’s group is the reason for the differences. To answer this question future studies should be undertaken. However, in our opinion, in vitro susceptibility testing of rifampicin can be used to predict resistance to rifaximin when done according to our method.

Rifaximin exhibits high activity against C. difficile in vitro, with a very low MIC50 and a very high MIC90 (0.032 µg ml−1 and 1024 µg ml−1, respectively). By using our suggested breakpoints (Table 4) as criteria for in vitro resistance, the prevalence of resistance was 7.5 % for all clinical isolates tested. Among the so-called hypervirulent ribotype RT 027, the prevalence of resistance was as high as 26 %. These data suggest that the development of resistance is in some way dependent on the PCR ribotype investigated; this is in concordance with general findings that some strains can become resistant more easily than others, e.g. C. difficile PCR ribotype 027, Mycobacterium tuberculosis spoligotype Beijing.

Susceptibility testing in the microbiology laboratory therefore could have an impact on the care and outcome of patients with infection (Doern et al., 1994). The rifaximin agar dilution and broth microdilution test systems facilitate reading of MICs and are often considered as gold standards for susceptibility testing. However, susceptibility testing by the disc diffusion method has the advantages of simplicity, low cost and a high degree of flexibility in the selection of agents tested (Richter & Ferraro, 2007). Our results show that rifaximin – despite its water-insolubility – may be a suitable candidate for disc diffusion testing. Whether 40 µg per disc is the ideal concentration must be examined in further studies. Whether it was prudent to officially license a substance ‘for treatment of all enteric infections caused by susceptible organisms’ also remains to be answered.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Marika Willerroider, Gebro Pharma GmbH (Fieberbrunn, Austria), for providing custom-made rifaximin discs. This work was supported by the ERA-NET project CDIFFGEN.

Abbreviation:

- CDI

Clostridium difficile infection

References

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2007). In Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Anaerobic Bacteria, approved standard, 7th edn. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [Google Scholar]

- Corazza G. R., Ventrucci M., Strocchi A., Sorge M., Pranzo L., Pezzilli R., Gasbarrini G. (1988). Treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth with rifaximin, a non-absorbable rifamycin. J Int Med Res 16, 312–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doern G. V., Vautour R., Gaudet M., Levy B. (1994). Clinical impact of rapid in vitro susceptibility testing and bacterial identification. J Clin Microbiol 32, 1757–1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST (2010). Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters, Version 1.1. http://www.srga.org/eucastwt/MICTAB/MICmiscellaneous.html

- Festi D., Mazzella G., Parini P., Ronchi M., Cipolla A., Orsini M., Sangermano A., Bazzoli F., Aldini R., Roda E. (1992). Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with non-absorbable antibiotics. Ital J Gastroenterol 24 Suppl. 214–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indra A., Huhulescu S., Schneeweis M., Hasenberger P., Kernbichler S., Fiedler A., Wewalka G., Allerberger F., Kuijper E. J. (2008). Characterization of Clostridium difficile isolates using capillary gel electrophoresis-based PCR ribotyping. J Med Microbiol 57, 1377–1382 10.1099/jmm.0.47714-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. D., Ke S., Palazzini E., Riopel L., Dupont H. (2000). In vitro activity and fecal concentration of rifaximin after oral administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44, 2205–2206 10.1128/AAC.44.8.2205-2206.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z. D., DuPont H. L., La Rocco M., Garey K. W. (2010). In vitro susceptibility of Clostridium difficile to rifaximin and rifampin in 359 consecutive isolates at a university hospital in Houston, Texas. J Clin Pathol 63, 355–358 10.1136/jcp.2009.071688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S., Schriever C., Galang M., Kelly C. P., Gerding D. N. (2007). Interruption of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea episodes by serial therapy with vancomycin and rifaximin. Clin Infect Dis 44, 846–848 10.1086/511870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato N., Ou C. Y., Kato H., Bartley S. L., Brown V. K., Dowell V. R. J., Jr, Ueno K. (1991). Identification of toxigenic Clostridium difficile by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol 29, 33–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H., Kato N., Katow S., Maegawa T., Nakamura S., Lyerly D. M. (1999). Deletions in the repeating sequences of the toxin A gene of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett 175, 197–203 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor J. R., Galang M. A., Sambol S. P., Hecht D. W., Vedantam G., Gerding D. N., Johnson S. (2008). Rifampin and rifaximin resistance in clinical isolates of Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52, 2813–2817 10.1128/AAC.00342-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenti F., Lancini G. (2003). Rifamycins. In Antibiotic and Chemotherapy, pp. 374–381 Edited by Finch R. G., Greenwood D., Norrby S. R., Whitley R. J. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone [Google Scholar]

- Richter S. S., Ferraro J. A. (2007). Susceptibility testing instrumentation and computerized expert systems for data analysis and interpretation. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology, pp. 245–256 Edited by Murray P. M., Baron E. J., Jorgensen J. H., Landry M. L., Pfaller M. A. Washington: American Society for Microbiology [Google Scholar]

- Ripa S., Mignini F., Prenna M., Falcioni E. (1987). In vitro antibacterial activity of rifaximin against Clostridium difficile, Campylobacter jejunii and Yersinia spp. Drugs Exp Clin Res 13, 483–488 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spigaglia P., Mastrantonio P. (2002). Molecular analysis of the pathogenicity locus and polymorphism in the putative negative regulator of toxin production (TcdC) among Clostridium difficile clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol 40, 3470–3475 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3470-3475.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struelens M. J. (2003). The problem of resistance. In Antibiotic and Chemotherapy, pp. 25–47 Edited by Finch R. G., Greenwood D., Norrby S. R., Whitley R. J. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs S. L., Brazier J. S., Talbot P. R., Duerden B. I. (2000). PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for identification of Bacteroides spp. and characterization of nitroimidazole resistance genes. J Clin Microbiol 38, 3209–3213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnidge J., Paterson D. L. (2007). Setting and revising antibacterial susceptibility breakpoints. Clin Microbiol Rev 20, 391–408 10.1128/CMR.00047-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg R. J., Claas E. C. J., Oyib D. H., Klaassen C. H. W., Dijkshoorn L., Brazier J. S., Kuijper E. J. (2004). Characterization of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile isolates from outbreaks in different countries by amplified fragment length polymorphism and PCR ribotyping. J Clin Microbiol 42, 1035–1041 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1035-1041.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willerroider M. (2009). Colidimin in neuer Packungsgröße. Medical Tribune 41, 17 [Google Scholar]

- Wiström J., Norrby S. R., Myhre E. B., Eriksson S., Granström G., Lagergren L., Englund G., Nord C. E., Svenungsson B. (2001). Frequency of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in 2462 antibiotic-treated hospitalized patients: a prospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother 47, 43–50 10.1093/jac/47.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]