Abstract

Dermatophytes are keratinophilic fungi that are the most common cause of fungal skin infections worldwide. Melanin has been isolated from several important human fungal pathogens, and the polymeric pigment is now recognized as an important virulence determinant. This study investigated whether dermatophytes, including Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Epidermophyton floccosum and Microsporum gypseum, produce melanin or melanin-like compounds in vitro and during infection. Digestion of the pigmented microconidia and macroconidia of dermatophytes with proteolytic enzymes, denaturant and hot concentrated acid yielded dark particles that retained the size and shape of the original fungal cells. Electron spin resonance spectroscopy revealed that particles derived from pigmented conidia contained a stable free radical signal, consistent with the pigments being a melanin. Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated reactivity of a melanin-binding mAb with the pigmented conidia and hyphae, as well as the isolate particles. Laccase, an enzyme involved in melanization, was detected in the dermatophytes by an agar plate assay using 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) as the substrate. Skin scrapings from patients with dermatophytoses contained septate hyphae and arthrospores that were reactive with the melanin-binding mAb. These findings indicate that dermatophytes can produce melanin or melanin-like compounds in vitro and during infection. Based on what is known about the function of melanin as a virulence factor of other pathogenic fungi, this pigment may have a similar role in the pathogenesis of dermatophytic diseases.

Introduction

Dermatophytes are highly specialized pathogenic fungi that cause dermatophytosis, superficial infections of the skin, hair and nails. These keratinophilic organisms cause disease by inducing host inflammation in response to fungal metabolic by-products (Ellis et al., 2000). The aetiological agents are from three genera, Trichophyton, Microsporum and Epidermophyton, based on the formation and morphology of their conidia (structures of asexual reproduction). According to their host preference and natural habitat, dermatophytes are generally grouped in three categories, anthropophilic (human), zoophilic (animal) and geophilic (soil). Dermatophytosis is among the most prevalent infections in the world, causing more than 20 % of these infections according to the World Health Organization (Marques, et al., 2000). Dermatophytes thrive at surface temperatures of 25–28 °C and skin mycosis is supported by warm and humid conditions. Due to these circumstances, superficial fungal infections are relatively common in tropical and subtropical countries where the hot climate and humid weather is favourable for the acquisition and maintenance of the disease (Hiruma & Yamaguchi, 2003). In Thailand, the incidence of dermatophyte infections is 38.1 % for onychomycosis and 42.1 % for tinea pedis compared with other fungal infections (Ungpakorn, 2005). In addition, Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes are the most frequently isolated dermatophytes from patients with onychomycosis and tinea pedis, respectively.

Melanins are dark brown or black biopolymer pigments formed by the oxidative polymerization of phenolic or indolic precursors, which also contain stable free radicals. They are widely synthesized by organisms of all living kingdoms and are characterized as being negatively charged amorphous compounds, degrading recalcitrants and being generally insoluble in aqueous and organic solvents (Butler & Day, 1998; Jacobson, 2000). Due to limitations of the biochemical and biophysical analytical methods, the structure of melanin is not yet fully established. A pigment can be identified as a melanin by using electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy, which directly detects the signal from a free radical. The ESR signal in derivative mode shows a narrow single peak located at approximately 3500 Gauss which is defined as the characteristic of all melanins (Enochs et al., 1993).

Melanins appear to provide considerable protection due to their remarkable biophysical properties, including resistance to microbial attack and enhancement of survival and longevity in fungi under environmental stress (Nosanchuk & Casadevall, 2003). Furthermore, melanins have attracted significant interest as putative virulence factors of several human pathogenic fungi, such as Cryptococcus neoformans (Nosanchuk et al., 2000; Rosas et al., 2000; Casadevall, et al., 2000), Aspergillus fumigatus (Jahn et al., 1997, 2000; Langfelder et al., 1998; Tsai et al., 1998, 1999; Youngchim et al., 2004; Pihet et al., 2009), Sporothrix schenckii (Romero-Martinez et al., 2000; Morris-Jones et al., 2003), Histoplasma capsulatum (Nosanchuk et al., 2002) and Penicillium marneffei (Youngchim et al., 2005). The ability of melanin to protect microbes from host defence mechanisms is well documented in C. neoformans (Nosanchuk & Casadevall, 2003), S. schenckii (Romero-Martinez et al., 2000), A. fumigatus (Jahn et al., 1997) and Fonsecaea pedrosoi (Cunha et al., 2010). Melanized cells of these fungi were more resistant to oxygen- and nitrogen-derived radicals than non-melanized cells. In addition, melanized cells of C. neoformans exhibit increased resistance to phagocytic killing, and reduce the susceptibility to some antifungal compounds (Nosanchuk & Casadevall, 2006). Apart from protecting fungal cells against host phagocytes, melanin has an additional role as an immunomodulatory effector that induces changes in cytokine/chemokine responses in C. neoformans (Mednick et al., 2005) and A. fumigatus (Chai et al., 2010).

Since the presence of melanin is associated with fungal virulence and pigmentation has been reported in dermatophytes (Kaben, 1967; Walker & Milovanovic, 1970; Schönborn, 1971; Ates et al., 2008), the objectives in our study were to investigate whether dermatophytes can synthesize melanin or melanin-like compounds both in vitro and in vivo by applying techniques developed to study and isolate melanin from P. marneffei (Youngchim et al., 2005).

Methods

Fungal strains and media.

The dermatophytes used in our study were clinical isolates. All of the isolates were obtained from the Institute of Dermatology, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health, Bangkok, Thailand. Stock cultures of dermatophyte species including Microsporum gypseum MMCM 5141, Epidermophyton floccosum MMCM 5132, T. mentagrophytes MMCM 5111 and T. rubrum MMCM 5121 were maintained by 6-monthly subculture onto slants of Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA; Difco) and storage at 4 °C under mineral oil. Dermatophytes were cultured on PDA for 4 weeks at room temperature (28 °C); conidia were then collected by adding 5 ml sterile PBS to the culture plate and removed by gentle scraping with a cotton swab. The conidia were collected by centrifugation at 8000 g for 30 min and they were then washed three times with sterile PBS.

Isolation and purification of melanin particles from dermatophytes.

Melanin was extracted from the conidia of dermatophytes M. gypseum, E. floccosum, T. mentagrophytes and T. rubrum following the protocol described by Wang et al. (1996). In brief, conidia were washed with sterile PBS followed by 1.0 M sorbitol and 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 5.5). Novozyme (a cell-wall-lysing enzyme from Trichoderma harzianum; Sigma) was added at 10 mg ml−1 and incubated overnight at 30 °C to generate protoplasts. The protoplasts were collected by centrifugation, washed three times with PBS and incubated in 4.0 M guanidine thiocyanate (Sigma) overnight at room temperature. The resultant dark particles were collected by centrifugation, washed three times with PBS and treated with 1.0 mg proteinase K ml−1(Roche) in reaction buffer [10.0 mM Tris, 1.0 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 % (w/v) SDS, pH 7.8] and incubated at 37 °C. The resultant debris was washed three times with PBS and boiled in 6.0 M HCl for 1.5 h. After treatment by boiling in acid, melanin particles were collected by filtration through Whatman paper no. 1 and were washed extensively with distilled water. Melanin particles were then dialysed against distilled water for 10 days until the acid was completely removed, whereupon they were lyophilized.

ESR spectroscopy analyses.

ESR spectroscopy is a technique that directly detects the signal from a free electron spin or free radical. Based on the properties of stable free radicals in melanin pigments, ESR is used as a tool to indicate the presence of melanin in the samples (Enochs et al., 1993). Using a Gunn diode as a microwave source, ESR spectroscopy was performed using 2 g freeze-dried material for each species examined (analysis was carried out in silica cuvettes). A. fumigatus melanin was used as a positive control.

Immunofluorescence analysis of melanin expression in dermatophytes.

Melanin particles derived from dermatophytes were fixed to slides and blocked with Superblock (Roche) overnight at 4 °C. Slide cultures of dermatophytes were prepared as described previously (Youngchim et al., 2005). Briefly, slide cultures were prepared in sterile Petri dishes by placing slides on sterile glass rods. PDA agar blocks cut into 1 cm squares were put on the slides and a small amount of the fungus was inoculated onto each of four sides of the agar block. Subsequently, a sterile cover glass was placed on the top of the inoculated agar block. For humidification, sterile cotton wool was put in the dish and two–three drops of sterile water were added. Plates were then sealed with masking tape and kept at room temperature for 2 weeks. Slides were periodically examined until conidiogenesis of fungi was complete. The slide cultures were released by removing the cover glass and the agar block from the slide. Before processing further, absolute ethanol was gently added onto the fungi on the slide, and the slides were left to dry in a sterile hood. The slides were washed three times with PBS, then incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C with 10 µg anti-melanin mAb 8D6 ml−1, an IgM melanin-binding mAb previously generated against A. fumigatus conidial melanin (Youngchim et al., 2004). The slides were washed in PBS and incubated in a 1 : 100 dilution of FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) for 2 h at 37 °C. The slides were washed three times with PBS to eliminate unbound antibody and then examined using an Olympus fluorescence microscope BX 51. For a negative control, conjugated goat-anti mouse IgM alone without primary mAb was included in the experiments. Images were captured with an Olympus SC 35.

Effect of melanin inhibitors.

Tricyclazole [an inhibitor of 1,8-dihydroxy naphthalene (DHN) melanin synthesis; Sigma], kojic acid (an inhibitor of 3,4-dihydroxy phenylalanine melanin synthesis; Sigma) and sulcotrione (an inhibitor of pyomelanin; Fluka), were used to identify the type of melanin. Tricyclazole was dissolved in absolute ethanol (EtOH) and added to minimal medium (15.0 mM glucose, 10.0 mM MgSO4, 29.4 mM K2HPO4, 13.0 mM glycine and 3.0 mM thiamine, pH 5.5) at a concentration of 1, 4, 8 and 16 µg ml−1. The concentration of EtOH in the culture medium was not more than 0.6 % (v/v). For controls, minimal medium with 1 % EtOH was included in the experiment to determine whether 1 % EtOH alone had any effect on pigment production of dermatophytes. In addition, kojic acid and sulcotrione were added to minimal medium at a concentration of 0, 10, 50 and 100 µg ml−1. All cultures were incubated at 28 °C for 4–6 weeks in the dark and examined for pigment production. After incubation, the conidia were harvested and subjected to melanin extraction as described above and analysed by ESR.

Detection of melanization of dermatophytosis from infected skin.

Skin scale specimens from patients with dermatophytosis were obtained from the Dermatological Clinic, Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, Chiang Mai University. Appropriate consent was provided by the patients and the procedure was approved by the ethics committee of Chiang Mai University. Direct examination of skin was performed and confirmed by culturing on Mycosel agar. To examine melanization, the skin was digested with 1.0 mg proteinase K ml−1 (Roche) at 37 °C for 2 h, and washed three times with PBS. The skin was then probed with the melanin-binding mAb 8D6 and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM as described above. Negative controls, without primary mAb, were included.

Plate assay of laccase activity.

A qualitative laccase assay in dermatophytes was modified from Srinivasan et al. (1995) and Crowe & Olsson (2001) by evaluating the oxidation of 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS; Sigma). The assay buffer used was a mixture of 0.1 M boric acid, 0.1 M acetic acid and 0.1 M phosphoric acid (Britton–Robinson buffer) adjusted to pH 5.0 with NaOH (Wahleithner et al., 1996). For the laccase plate assay, which allowed rapid determination of the presence of laccase, 15 ml melting sterile agar (2.0 %) medium with 4 mM ABTS was placed in a sterile Petri dish (90×15 mm) containing three sterile cups (6 mm in diameter). The cups were removed after the agar was solidified. In each well, 200 µl whole cell suspension (adjusted to McFarland standard no. 5) suspended in sterile PBS was inoculated and the laccase plates were incubated at 28 °C for 2–3 days. C. neoformans H99 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae MMCM 5211 were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. All plates were inspected daily for pigment production. The development of an intense bluish green colour around the wells was considered to be a positive reaction for laccase activity.

Results

Melanization of dermatophytes in vitro

ESR spectroscopy.

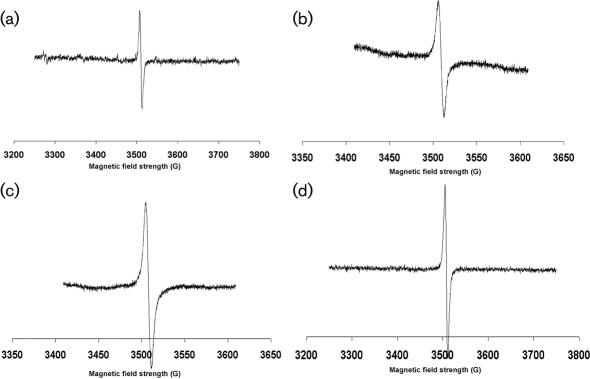

ESR spectroscopy of dark particles extracted from M. gypseum, T. mentagrophytes, T. rubrum and E. floccosum produced signals indicating the presence of a stable free-radical signal (Fig. 1), which is the defining feature of all melanins (Enochs et al., 1993). Based on the ESR spectra, they were identified as melanins. The spectra were equivalent to the signals generated with melanins of C. neoformans (Wang et al., 1996), P. brasiliensis (Gómez et al., 2001), H. capsulatum (Nosanchuk et al., 2002), A. fumigatus (Youngchim et al., 2004) and Sporothrix schenckii (Morris-Jones et al., 2003).

Fig. 1.

ESR spectroscopy of melanin particles extracted from E. floccosum (a), T. rubrum (b), T. mentagrophytes (c) and M. gypseum (d). 1 gauss = 1×10−4 tesla.

Immunofluorescence reactivity of the anti-melanin mAb 8D6 to dermatophyte conidia before and after melanin extraction.

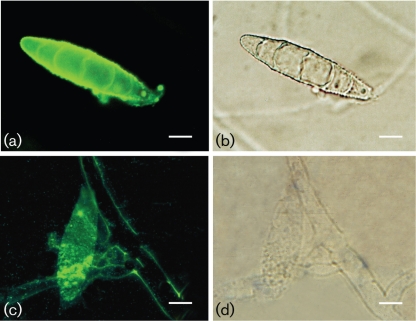

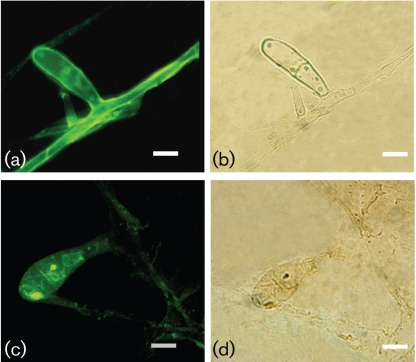

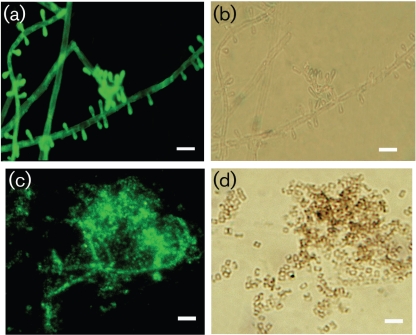

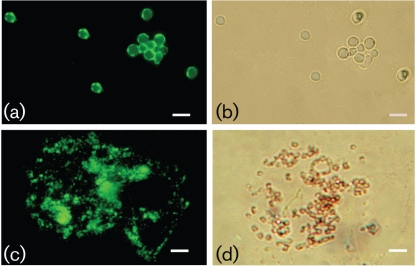

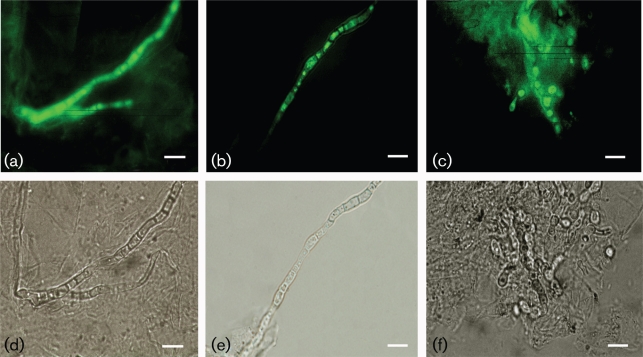

The melanin-binding mAb 8D6 reacted strongly to pigmented macroconidia of M. gypseum and E. floccosum, with a pronounced fluorescent reactivity located within the cell wall of conidia (Figs 2 and 3, respectively). The images also demonstrate differences in the presence of melanins within hyphal structures. Cellular structures masked M. gypseum hyphal structures, but a thin melanin layer was revealed after treatment of the cells with denaturants and hot acid. In contrast, mAb 8D6 reacted more strongly with the intact hyphal structure of E. floccosum than with structures recovered after melanin isolation, suggesting that some of the melanin in this species may be either extractable or solubilizable. Furthermore, microconidia of both T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes were also strongly reactive with mAb 8D6 in Figs 4 and 5, respectively. After the melanin extraction procedure, the resultant particles in dermatophytes retained reactivity to mAb 8D6 with identical patterns of labelling to their propagules. No reactivity was observed when the unspecific mAb 5C11 was used or when FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse IgM was used alone.

Fig. 2.

Corresponding immunofluorescence (a, c) and bright-field (b, d) microscopy images demonstrating the labelling of macroconidia of M. gypseum before (a, b) and after (c, d) melanin extraction by the melanin-binding mAb 8D6. For a negative control, conjugated goat–anti-mouse IgM alone without primary mAb was included in the experiments. Bars, 10 µm.

Fig. 3.

Corresponding immunofluorescence (a, c) and bright-field (b, d) microscopy images demonstrating the labelling of macroconidia from E. floccosum before (a, b) and after (c, d) melanin extraction by the melanin-binding mAb 8D6. No reactivity was observed when FITC-labelled goat–anti-mouse IgM was used alone. Bars, 10 µm.

Fig. 4.

Corresponding immunofluorescence (a, c) and bright-field (b, d) microscopy images demonstrating the labelling of microconidia from T. rubrum before (a, b) and after (c, d) melanin extraction by the melanin-binding mAb 8D6. No reactivity was observed when FITC-labelled goat–anti-mouse IgM was used alone. Bars, 5 µm.

Fig. 5.

Corresponding immunofluorescence (a, c) and bright-field (b, d) microscopy images demonstrating the labelling of microconidia from T. mentagrophytes before (a, b) and after (c, d) melanin extraction by the melanin-binding mAb 8D6. No reactivity was observed when FITC-labelled goat–anti-mouse IgM was used alone. Bars, 5 µm.

Effect of melanin inhibitors on melanization.

Tricyclazole had no effect on pigment synthesis in dermatophytes under the conditions examined, even when the concentration was increased to 16 µg ml−1(Supplementary Fig. S1, available with the online version of this paper). When examined by using the melanin-binding mAb 8D6, there were no differences in binding between cells incubated with or without tricyclazole (data not shown). Moreover, melanin particles were readily extracted from dermatophytes cultured on minimal medium with 16 µg tricyclazole ml−1, and the ESR spectra of these particles were identical to the signals generated with melanins (data not shown). The other two melanin inhibitors, kojic acid and sulcotrione, failed to inhibit conidial pigmentation of dermatophytes, even when the concentration of inhibitors was increased to 100 μg ml−1 (Supplementary Fig. S1). In addition, black particles were isolated from dermatophytes during culturing on minimal medium with 100 μg kojic acid or sulcotrione ml−1, and the ESR spectra of the black particles were identical to the signal generated with melanins (data not shown).

Detection of melanization in dermatophytes obtained from human skin

Skin scrapings from three patients with dermatophytosis were stained by KOH preparation to confirm the presence of septate hyphae in tissue. In addition, these three samples of skin scrapings were also shown to be positive for cultures of dermatophytes: T. rubrum in two samples and T. mentagrophytes in one sample. The identified septate hyphae were strongly reactive with melanin-binding mAb 8D6 (Fig. 6). No reactivity was observed when an unspecific mAb was used or when FITC-labelled mAb was used alone.

Fig. 6.

Corresponding immunofluorescence (a–c) and bright-field (d–f) microscopy images demonstrating the labelling of septate hyphae and arthrospores from skin scrapings of patients with dermatophytoses by the melanin-binding mAb 8D6. A negative control was included. Bars, 5 µm.

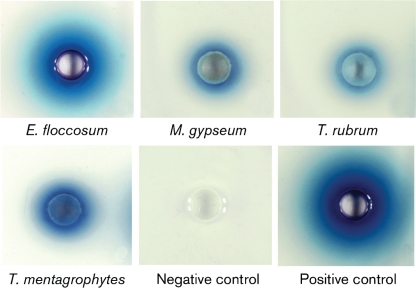

Laccase plate assay

Laccase plate assays were based on the ability of an organism to oxidize ABTS incorporated into the media, resulting in intense bluish green colour production around the wells of dermatophyte suspensions. The results of the laccase plate assay (Fig. 7) demonstrated the presence of laccase activity in cell suspensions of all dermatophytes tested and in C. neoformans (positive control), but no reactivity occurred with S. cerevisiae (negative control). These results showed that the plate assay can also be utilized as a simple rapid assay to visually demonstrate the existence of laccase activity in dermatophytes.

Fig. 7.

Plate assay to demonstrate laccase activity in dermatophytes. Dermatophytes E. floccosum, M. gypseum, T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes were inoculated into the laccase plate assay containing 4 mM ABTS as the substrate. S. cerevisiae MMCM 5211 and C. neoformans H99 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. The development of an intense bluish green colour around the wells indicated a positive result for laccase activity.

Discussion

In our studies, the evidence supporting the melanization of dermatophytes in vitro is as follows: (i) treatment of conidia with the melanin extraction protocol resulted in the isolation of black particles similar in size and shape to their corresponding propagules; (ii) ESR spectroscopy analysis of these black particles revealed the presence of a stable free radical compound consistent with melanin; (iii) a melanin-binding mAb reacts with the cell wall of macroconidia and microconidia in dermatophytes and with pigmented particles derived from these cells; and (iv) laccase activity was detected in dermatophytes. Taken together, these results provide solid evidence that dermatophytes can produce melanin in vitro.

The detection of laccase-like activity by measuring the oxidation of ABTS is consistent with the occurrence of a laccase-like enzyme in dermatophytes, which supports the formation of melanin in these fungi. It is noteworthy that Jung et al. (2002) previously purified and characterized a laccase in a T. rubrum isolate from a decayed hardwood chip pile. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purported T. rubrum laccase protein displayed high homology with published laccase protein sequences of wood-degrading basidiomycetous fungi, but little similarity to laccases from C. neoformans. Conversely, the protein sequences of a putative laccase of T. mentagrophytes identified by protein blast (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) was closely related to several dermatophytic laccases, showing 98, 91 and 88 % identity to T. rubrum, M. gypseum and M. canis, respectively. Moreover, the protein sequences of T. mentagrophytes laccase had a high degree of similarity to other fungal laccases, 59 % to A. niger and 57 % to P. marneffei. Laccase not only catalysed the synthesis of melanin but has also been shown to be an important virulence factor in fungal infection. For example, C. neoformans laccase is involved in the regulation of iron in macrophages by acting as an iron oxidase and reducing the killing of C. neoformans by hydroxyl radicals generated in vitro (Liu et al., 1999). Given that the secretion of enzymes has been associated with virulence in dermatophytes and that fungal laccases can be secreted (Zhu et al., 2001; Rodrigues et al., 2008), it is likely that dermatophyte laccase may contribute to virulence in ways other than its putative role in catalysing melanin polymerization.

In the initial melanin inhibition assays of dermatophytes, tricyclazole, a specific inhibitor of DHN melanin biosynthesis, had no effect on pigmentation of these fungi, raising the possibility that the melanin pathway may be different or more complex in dermatophytes. Previously, the studies by Mares et al. (2004) had shown that tricyclazole at higher concentrations, 100 and 200 µg ml−1 were also ineffective in impeding pigmentation of both T. rubrum and E. floccosum, but these concentrations affected fungal growth. Although pigmentation of the dermatophytes was not susceptible to tricyclazole, there is still no definite proof that dermatophytes did not produce pigment via the DHN melanin pathway. According to the studies of the melanin biosynthesis pathway in P. marneffei, the polyketide synthase (PKS) genes have been characterized and identified, which implied a role for the DHN melanin pathway in this dimorphic fungus (Woo et al., 2010). However, tricyclazole also fails to inhibit pigmentation in P. marneffei in which the DHN-melanin biosynthesis pathway is expected to be active [as is also the case in A. nidulans (O’Hara & Timberlake, 1989) and A. parasiticus (Brown et al., 1993)]. Based on protein sequence similarity using the NCBI-blast search system, PKS involved in DHN melanin biosynthesis of M. gypseum displayed a high degree of homology to A. fumigatus (77 %) and A. nidulans (64 %), and a higher degree to T. mentagrophytes (87 %) and T. rubrum (87 %). Thus, more detailed analyses of the melanin biosynthesis pathway in dermatophytes using further melanization inhibitors and molecular techniques should be undertaken in the future.

In addition to the melanin-binding mAb 8D6 reacting with dermatophyte cells obtained from culture, the mAb labelled septate hyphae in infected skin, suggesting that melanization is not simply an in vitro phenomenon and that pigment formation may be associated with the pathobiology of these fungi. Correspondingly, a previous study by Perrin & Baran (1994) found melanization of T. rubrum in vivo by using Masson–Fontana silver stain which exhibited a brown cytoplasmic pigment in hyphae from nail samples. However, although it has now been demonstrated that both in vitro and in vivo melanization occurs in dermatophytes, no direct link has yet been established between the prevalence of melanin in these organisms and virulence. This question awaits further analyses which requires the production of melanin-deficient dermatophyte mutants and their testing in animal models.

Melanins represent virulence factors in several important fungal pathogens; however, at this time we have no available data to suggest that melanin plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of dermatophytosis. With antifungals being more commonly used to treat various fungal infections in the growing population of immunocompromised patients, it is prudent to be concerned about the possible emergence of resistant strains. Thus, effective control of dermatophytes will necessarily involve the development of a new generation of potent broad-spectrum antifungals with selective action against new targets in the fungal cells, and melanin has been considered as a target for drug development (Nosanchuk et al., 2001). Hence, understanding the physiopathogenesis of these infections is essential for preventing and treating them efficiently.

In conclusion, our results indicate that dermatophytes, including T. mentagrophytes, T. rubrum, E. floccosum and M. gypseum, can synthesize melanin or melanin-like pigments when grown in vitro and that these pigments are present in septate hyphae in dermatophyte-infected skin. These findings validate future investigations targeting melanin in recalcitrant dermatophytic diseases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Fund of Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, 50200, Thailand. J. D. N. was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grants AI52733 and AI056070-01A2.

Abbreviations

- : ABTS

2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- DHN

1,8-dihydroxy napthalene

- ESR

electron spin resonance

- PKS

polyketide synthase

A supplementary figure is available with the online version of this paper.

References

- Ates A., Ozcan K., Ilkit M. (2008). Diagnostic value of morphological, physiological and biochemical tests in distinguishing Trichophyton rubrum from Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex. Med Mycol 46, 811–822. 10.1080/13693780802108458.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. W., Hauser F. M., Tommasi R., Corlett S., Salvo J. J. (1993). Structural elucidation of a putative conidial pigment intermediate in Aspergillus parasiticus. Tetrahedron Lett 34, 419–422. 10.1016/0040-4039(93)85091-A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. J., Day A. W. (1998). Fungal melanins: a review. Can J Microbiol 44, 1115–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A., Rosas A. L., Nosanchuk J. D. (2000). Melanin and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Curr Opin Microbiol 3, 354–358. 10.1016/S1369-5274(00)00103-X.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai L. Y., Netea M. G., Sugui J., Vonk A. G., van de Sande W. W., Warris A., Kwon-Chung K. J., Kullberg B. J. (2010). Aspergillus fumigatus conidial melanin modulates host cytokine response. Immunobiology 215, 915–920. 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.10.002.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe J. D., Olsson S. (2001). Induction of laccase activity in Rhizoctonia solani by antagonistic Pseudomonas fluorescens strains and a range of chemical treatments. Appl Environ Microbiol 67, 2088–2094. 10.1128/AEM.67.5.2088-2094.2001.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha M. M., Franzen A. J., Seabra S. H., Herbst M. H., Vugman N. V., Borba L. P., de Souza W., Rozental S. (2010). Melanin in Fonsecaea pedrosoi: a trap for oxidative radicals. BMC Microbiol 10, 80–89. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-80.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis D., Marriott D., Hajjeh R. A., Warnock D., Meyer W., Barton R. (2000). Epidemiology: surveillance of fungal infections. Med Mycol 38 Suppl. 1, 173–182.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enochs W. S., Nilges M. J., Swartz H. M. (1993). A standardized test for the identification and characterization of melanins using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. Pigment Cell Res 6, 91–99. 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1993.tb00587.x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez B. L., Nosanchuk J. D., Díez S., Youngchim S., Aisen P., Cano L. E., Restrepo A., Casadevall A., Hamilton A. J. (2001). Detection of melanin-like pigments in the dimorphic fungal pathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis in vitro and during infection. Infect Immun 69, 5760–5767. 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5760-5767.2001.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma M., Yamaguchi H. (2003). Dermatophytes. In Clinical Mycology, pp. 370–379. Edited by Anaissie E. J., McGinnis M. R., Pfaller M. A. The Curtis Center, PA: Churchill Livingstone Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson E. S. (2000). Pathogenic roles for fungal melanins. Clin Microbiol Rev 13, 708–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn B., Koch A., Schmidt A., Wanner G., Gehringer H., Bhakdi S., Brakhage A. A. (1997). Isolation and characterization of a pigmentless-conidium mutant of Aspergillus fumigatus with altered conidial surface and reduced virulence. Infect Immun 65, 5110–5117.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn B., Boukhallouk F., Lotz J., Langfelder K., Wanner G., Brakhage A. A. (2000). Interaction of human phagocytes with pigmentless Aspergillus conidia. Infect Immun 68, 3736–3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H., Xu F., Li K. (2002). Purification and characterization of laccase from wood-degrading fungus Trichophyton rubrum LKY-7. Enzyme Microb Technol 30, 161–168. 10.1016/S0141-0229(01)00485-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaben U. (1967). [Dermatolycoses and dermatophyte flora in the adminission region of the university dermatological clinic of Rostock in the years 1961 to 1965 (with special consideration of Trichopyton rubrum species with melanoid pigment)]. Dermatol Wochenschr 153, 1112–1122 (in German).. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder K., Jahn B., Gehringer H., Schmidt A., Wanner G., Brakhage A. A. (1998). Identification of a polyketide synthase gene (pksP) of Aspergillus fumigatus involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis and virulence. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl) 187, 79–89. 10.1007/s004300050077.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Tewari R. P., Williamson P. R. (1999). Laccase protects Cryptococcus neoformans from antifungal activity of alveolar macrophages. Infect Immun 67, 6034–6039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares D., Romagnoli C., Andreotti E., Manfrini M., Vicentini C. B. (2004). Synthesis and antifungal action of new tricyclazole analogues. J Agric Food Chem 52, 2003–2009. 10.1021/jf030695y.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques S. A., Robles A. M., Tortorano A. M., Tuculet M. A., Negroni R., Mendes R. P. (2000). Mycoses associated with AIDS in the Third World. Med Mycol 38 Suppl. 1, 269–279.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mednick A. J., Nosanchuk J. D., Casadevall A. (2005). Melanization of Cryptococcus neoformans affects lung inflammatory responses during cryptococcal infection. Infect Immun 73, 2012–2019. 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2012-2019.2005.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Jones R., Youngchim S., Gómez B. L., Aisen P., Hay R. J., Nosanchuk J. D., Casadevall A., Hamilton A. J. (2003). Synthesis of melanin-like pigments by Sporothrix schenckii in vitro and during mammalian infection. Infect Immun 71, 4026–4033. 10.1128/IAI.71.7.4026-4033.2003.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosanchuk J. D., Casadevall A. (2003). The contribution of melanin to microbial pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol 5, 203–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosanchuk J. D., Casadevall A. (2006). Impact of melanin on microbial virulence and clinical resistance to antimicrobial compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50, 3519–3528. 10.1128/AAC.00545-06.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosanchuk J. D., Rosas A. L., Lee S. C., Casadevall A. (2000). Melanisation of Cryptococcus neoformans in human brain tissue. Lancet 355, 2049–2050. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02356-4.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosanchuk J. D., Ovalle R., Casadevall A. (2001). Glyphosate inhibits melanization of Cryptococcus neoformans and prolongs survival of mice after systemic infection. J Infect Dis 183, 1093–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosanchuk J. D., Gómez B. L., Youngchim S., Díez S., Aisen P., Zancopé-Oliveira R. M., Restrepo A., Casadevall A., Hamilton A. J. (2002). Histoplasma capsulatum synthesizes melanin-like pigments in vitro and during mammalian infection. Infect Immun 70, 5124–5131. 10.1128/IAI.70.9.5124-5131.2002.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara E. B., Timberlake W. E. (1989). Molecular characterization of the Aspergillus nidulans yA locus. Genetics 121, 249–254.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin C., Baran R. (1994). Longitudinal melanonychia caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Histochemical and ultrastructural study of two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 31, 311–316. 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70161-X.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihet M., Vandeputte P., Tronchin G., Renier G., Saulnier P., Georgeault S., Mallet R., Chabasse D., Symoens F., Bouchara J. P. (2009). Melanin is an essential component for the integrity of the cell wall of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. BMC Microbiol 9, 177–188. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-177.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M. L., Nakayasu E. S., Oliveira D. L., Nimrichter L., Nosanchuk J. D., Almeida I. C., Casadevall A. (2008). Extracellular vesicles produced by Cryptococcus neoformans contain protein components associated with virulence. Eukaryot Cell 7, 58–67. 10.1128/EC.00370-07.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Martinez R., Wheeler M., Guerrero-Plata A., Rico G., Torres-Guerrero H. (2000). Biosynthesis and functions of melanin in Sporothrix schenckii. Infect Immun 68, 3696–3703. 10.1128/IAI.68.6.3696-3703.2000.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas A. L., Nosanchuk J. D., Feldmesser M., Cox G. M., McDade H. C., Casadevall A. (2000). Synthesis of polymerized melanin by Cryptococcus neoformans in infected rodents. Infect Immun 68, 2845–2853. 10.1128/IAI.68.5.2845-2853.2000.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönborn C. (1971). Dermatophytes with melanoid pigment. 1. Occurrence of pigment-forming fungal strains and intensity of their pigment production. Z Gesamte Hyg 17, 773–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan C., Dsouza T. M., Boominathan K., Reddy C. A. (1995). Demonstration of laccase in the white rot Basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium BKM-F1767. Appl Environ Microbiol 61, 4274–4277.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H. F., Chang Y. C., Washburn R. G., Wheeler M. H., Kwon-Chung K. J. (1998). The developmentally regulated alb1 gene of Aspergillus fumigatus: its role in modulation of conidial morphology and virulence. J Bacteriol 180, 3031–3038.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H. F., Wheeler M. H., Chang Y. C., Kwon-Chung K. J. (1999). A developmentally regulated gene cluster involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. J Bacteriol 181, 6469–6477.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungpakorn R. (2005). Mycoses in Thailand: current concerns. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 46, 81–86. 10.3314/jjmm.46.81.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahleithner J. A., Xu F., Brown K. M., Brown S. H., Golightly E. J., Halkier T., Kauppinen S., Pederson A., Schneider P. (1996). The identification and characterization of four laccases from the plant pathogenic fungus Rhizoctonia solani. Curr Genet 29, 395–403. 10.1007/BF02208621.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker G. C., Milovanovic D. (1970). Pigment formation in the dermatophytes. Mycopathol Mycol Appl 42, 369–379. 10.1007/BF02051962.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Aisen P., Casadevall A. (1996). Melanin, melanin "ghosts," and melanin composition in Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun 64, 2420–2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P. C., Tam E. W., Chong K. T., Cai J. J., Tung E. T., Ngan A. H., Lau S. K., Yuen K. Y. (2010). High diversity of polyketide synthase genes and the melanin biosynthesis gene cluster in Penicillium marneffei. FEBS J 277, 3750–3758. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07776.x.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngchim S., Morris-Jones R., Hay R. J., Hamilton A. J. (2004). Production of melanin by Aspergillus fumigatus. J Med Microbiol 53, 175–181. 10.1099/jmm.0.05421-0.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngchim S., Hay R. J., Hamilton A. J. (2005). Melanization of Penicillium marneffei in vitro and in vivo. Microbiology 151, 291–299. 10.1099/mic.0.27433-0.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Gibbons J., Garcia-Rivera J., Casadevall A., Williamson P. R. (2001). Laccase of Cryptococcus neoformans is a cell wall-associated virulence factor. Infect Immun 69, 5589–5596. 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5589-5596.2001.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]