Abstract

Fibromatosis colli is a peculiar, benign fibrous growth of the sternocleidomastoid that usually appears during the first few weeks of life and is often associated with muscular torticollis. Fibromatosis colli (FC) is seen in children born after difficult, prolonged labor, assisted delivery, and breech deliveries. Clinically, FC has to be differentiated from congenital lesions, inflammatory lesions, and neoplastic conditions—both benign and malignant—that may occur at that site. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is a simple technique that will help in excluding the above conditions and also in avoiding surgical procedures. Fibromatosis colli also resembles other forms of infantile fibromatosis, but its behavior, microscopic appearance, and its treatment distinguish it from other forms of infantile fibromatosis. In contrast to other forms of fibromatosis, a noninvasive, conservative management is usually the line of treatment for FC in most of the cases. FNAC is a noninvasive method of diagnosis of FC that is thus useful in its management. We report here a case of Fibromatosis colli diagnosed by FNAC.

Keywords: Aspiration, fibromatosis colli, infant, newborn, sternocleidomastoid tumor

Introduction

Fibromatosis colli (FC) also known as sternocleidomastoid tumor, a self limiting lesion, presents as a firm to hard, immobile, fusiform swelling in the lower or middle portion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and usually appears within the first few weeks of life. Most of the cases present with torticollis but there are exceptions. Birth injury is supposed to play an important role in the pathogenesis, which is otherwise debatable as some of the cases do not have any history of birth injury.[1] As the treatment of FC is usually conservative and avoids surgical procedures by employing physiotherapy, the diagnostic, noninvasive technique of fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) becomes important. FC has to be differentiated from congenital lesions, inflammatory lesions, neoplastic conditions—both benign and malignant—and other forms of infantile fibromatosis that may occur at that site.[2] FC can be differentiated from other forms of infantile fibromatosis on the basis of the clinical features such as age, site, infiltrative pattern, and cytological features such as bland-appearing fibroblasts, degenerative, atrophic skeletal muscle, and muscle giant cells without inflammatory cells in a clean background.[2–6] In contrast to other forms of fibromatosis, a noninvasive, conservative management is usually the line of treatment for FC in most of the cases. FNAC is a noninvasive method of diagnosis of FC that is thus useful in its management. We report here a case of a one month-old child with FC diagnosed by FNAC and treated conservatively.

Case Report

A one month-old, male child delivered by forceps was being treated for right sided Erb's palsy in the Physiotherapy Department. At the time, a 2×2 cm, firm to hard swelling was noticed in the left side of the neck at the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle along with restricted mobility. FNAC was done using a 23 gauge needle.

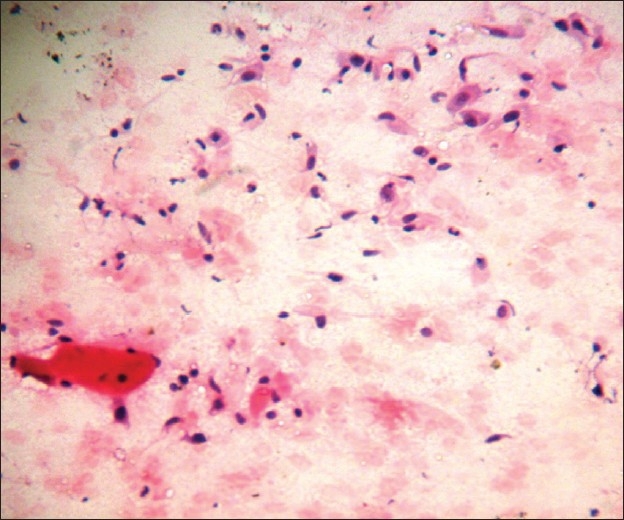

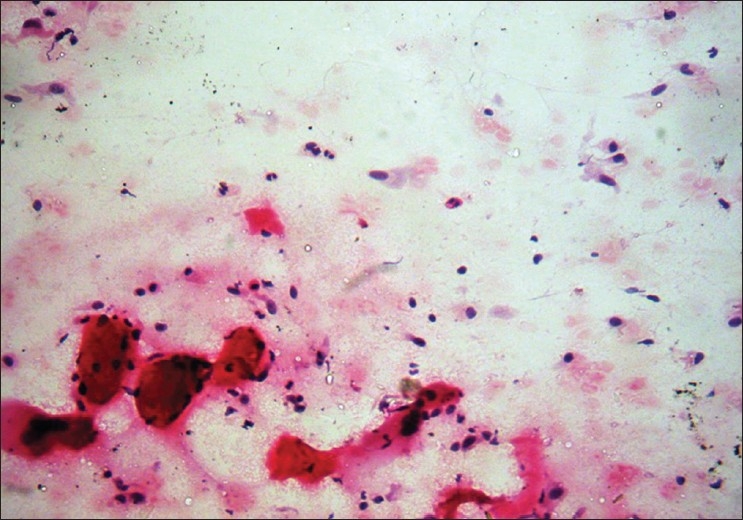

Microscopy revealed single and sheets of spindle-shaped cells [Figure 1]. The sheets of cells showed streaming in foci and the cytoplasm was eosinophilic with plump nuclei. Also seen were atrophic skeletal muscle fibers and regenerating muscle giant cells [Figure 2]. The background was clean without inflammatory cells and hemorrhage or necrosis. A diagnosis of FC was made based on the above findings.

Figure 1.

Single and sheets of spindle-shaped cells with atrophic muscle fibers (H and E, ×400)

Figure 2.

Atrophic skeletal muscle fibers and regenerating muscle giant cells (H and E, ×400)

Discussion

FC is a self-limiting, benign tumor of infancy, presenting shortly after birth.[1] It disappears within the first year of life without any need for surgical intervention. The cause of the growth is debatable,[1] but is usually associated with difficult or assisted labor and breech deliveries. Birth injury resulting in ischemia may be the likely cause but it may also be probable that the growth is the cause rather than the effect of abnormal labor.[1] Another theory is that the growth is a peculiar, hamartomatous process that is unrelated to birth injury or vascular impairment. Clinically, FC has to be differentiated from congenital lesions such as branchial cleft cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts, inflammatory lesions like tuberculous lymphadenitis, benign neoplastic conditions like hemangioma, cystic hygroma, lipoma, and malignant neoplasms like neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and lymphoma.[2] A simple, noninvasive FNAC will help in ruling out the above conditions. The cytomorphological features of FC are distinct with bland-appearing fibroblasts and degenerative, atrophic skeletal muscle in a clear background without any evidence of inflammation or hemorrhage. Large numbers of mature and immature skeletal muscle fibres, muscle giant cells; numerous, plump fibroblasts; and collagen have been found along with a number of bland, bare nuclei in the background. [2–6]

Other infantile fibromatosis which tend to resemble FC can be differentiated on the basis of clinical features such as age, site, and infiltrative pattern and also, based on certain cytological features.

Cytologically, FC is differentiated from nodular fasciitis by the pleomorphism of proliferating fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with ovoid or kidney-shaped nuclei. Bi- and multinucleated forms may be seen in a myxoid background along with inflammatory cells.[7] Other infantile fibromatoses can be differentiated on the basis of clinical features such as age, site, and infiltrative pattern and based on cytological features including collagen fragments and spindly nuclei.[5]

FC can be diagnosed by FNAC, a noninvasive procedure, with newer, nonsurgical treatment procedures resulting in the regression of the lesions in 90% of cases.[8]

We report here a case of FC diagnosed by FNAC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Preeti Avinash for helping in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Enzinger and Weiss's Soft tissue tumors. 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2001. Fibrous tumors of infancy and childhood; pp. 273–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma S, Mishra K, Khanna G. Fibromatosis Colli in infants: A cytologic study of eight cases. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:359–62. doi: 10.1159/000326533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raab SS, Silverman JF, McLeod DL, Benning TL, Geisinger KR. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of fibromatoses. Acta Cytol. 1993;37:323–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apple SK, Nieberg RK, Hirschowitz SL. Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of fibromatosis colli: A report of three cases. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:1373–6. doi: 10.1159/000333540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akerman M. Soft tissues. In: Orell SR, Sterrett GF, Whitaker D, editors. Fine needle aspiration cytology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereira S, Tani E, Skoog L. Diagnosis of fibromatosis colli by fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology. Cytopathology. 1999;10:25–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.1999.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahl I, Akerman M. Nodular fasciitis a correlative cytologic and histologic study of 13 cases. Acta Cytol. 1981;25:215–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffin CM, Dehner LP. The soft tissues. In: Stocker JT, Dehner LP, editors. Pediatric pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. p. 1181. [Google Scholar]