Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the role of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the distinction between neoplastic and nonneoplastic ovarian masses.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and twenty patients with ovarian masses were studied. After detailed history and clinical examination, ultrasound (USG)-guided FNAC was performed in 92 clinical benign cases while FNAC and/or imprints of surgically resected ovarian masses was performed in 28 clinically suspected malignant cases. The smears were stained with Papanicolaou stain and histopathological sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain with inclusion of special stain whenever required. Serum β-human chorionic gonadotrophin and α-fetoprotein estimations were carried out in cytologically diagnosed germ cell tumors.

Results:

The overall sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of FNAC in diagnosing various ovarian masses were 79.2%, 90.6% and 89.9%, respectively.

Conclusions:

The clinical examination, pelvic ultrasound and FNAC were complementary and none of the methods was, in itself, diagnostic. However, USG-guided FNAC was found to be a fairly specific and accurate technique and should be employed as a routine, especially in young females with clinically benign ovarian lesions. The reasons for false diagnosis and limitations of USG and FNAC have been analyzed.

Keywords: FNAC, neoplastic and nonneoplastic lesions, ovarian masses

Introduction

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is a simple and reliable method for the diagnosis of a variety of female genital tract tumors.[1] Previous workers have established the criteria for cytomorphologic diagnosis of ovarian tumors.[2,3] However, till today, gynaecologists all over the world are hesitant to accept the role of FNAC on pelvic masses because of the controversial opinion about the potential risk of intraperitoneal tumor implantation, particularly of ovarian tumors,[4] although the risk of carcinoma (CA) cell seeding within the abdominal cavity due to contamination by needles is overestimated[5] and has not been clinically or pathologically documented.[6] FNAC, guided by ultrasonography (USG) or laparoscopy, has become an important tool in the management of ovarian cysts, particularly in young women with suspected functional cysts.[7] Geier and Strecker[8] have suggested that FNAC should be used for (1) recurrent and metastatic tumors, (2) suspected benign ovarian cysts and (3) when the patient's condition is unsuitable for laparotomy. The present study was carried out to evaluate the role of aspiration cytology in the distinction between neoplastic and nonneoplastic ovarian lesions and to analyse the diagnostic pitfalls of sonography and cytology.

Materials and Methods

One hundred and twenty cases of different types of pelvic masses clinically diagnosed as ovarian lesions were studied. The patients were between 13 and 58 years of age. After clinical examination, specific sonographic parameters were considered in an attempt to reliably distinguish between benign and malignant ovarian tumors, such as size, echogenecity, wall thickness, septations and solid areas. Of the total cases, 92 clinical benign ovarian lesions were subjected to USG-guided FNAC using a 20 CC syringe and a 22 gauge needle. In vitro aspiration (in surgically resected specimens) was performed in 28 clinically diagnosed malignant ovarian lesions. The sizes of the ovarian masses were recorded before aspiration. Four smears (two cytospin and two direct) were prepared, fixed in 95% ethanol and stained with Papanicolaou stain (Pap). The smears were evaluated for the following parameters: cellularity, arrangement of cells, type of epithelial cells, foamy/hemosiderin-laden macrophages, calcified/necrotic material and proteinaceous, granular, greasy or mucoid background. Based on cytomorphology, the lesions were classified as (1) nonneoplastic cysts, (2) benign neoplasms and (3) malignant neoplasms. Cases with inadequate cellularity were omitted from the study. Hematoxylin and eosin (H and E)-stained histologic sections were available in all the cases. Special stains were employed as and when required.

Results

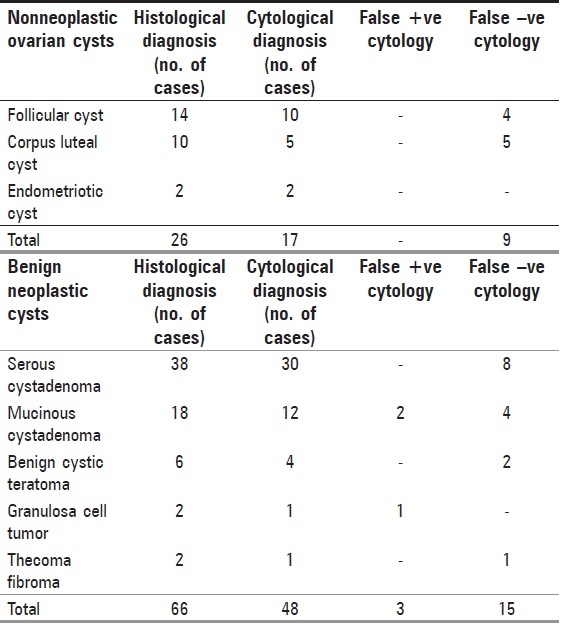

Ninety-two cases of a total of 120 were diagnosed by FNAC as benign ovarian lesions, which included nonneoplastic cysts (26 cases) and benign ovarian neoplasms (66 cases), whereas 28 cases were diagnosed as malignant lesions [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Cytohistological correlation of nonneoplsatic and benign neoplastic ovarian cysts

Table 2.

Cytohistological correlation of malignant ovarian masses

There were 17 of 26 cytologically diagnosed nonneoplastic ovarian cysts. Nine cases could not be categorized either due to nonspecific findings or due to inadequate cytological material [Table 1].

The benign neoplasms comprised of simple serous cystadenoma (38 cases), mucinous cystadenoma (18 cases), benign cystic teratoma (6), granulosa cell tumor (2 cases) and fibroma (2 cases) of the ovary in decreasing order of frequency. Forty-eight of these 66 benign ovarian masses were confirmed by histology. False diagnosis occurred in 18 cases, which included eight cases of serous cystadenoma, six cases of mucinous cystadenoma, two cases of benign cystic teratoma and one case each of granulosa cell tumor and thecoma-fibroma [Table 1].

Twenty-eight of the 120 were diagnosed as malignant neoplasms by FNAC performed in resected specimens, which consisted of serous (13), mucinous cyst-adenocarcinoma (10), dysgerminoma (2), one case each of undifferentiated CA, yolk sac tumor and embryonal CA in decreasing frequency. Twenty-four of these 28 cases were confirmed by histology. Three cases proved to be false-positive, which included one case each of borderline serous and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma and metastatic CA [Table 2].

Discussion

All nonneoplastic cysts measured <8.0 cm in diameter and were found in women <40 years of age, whereas all benign and malignant neoplastic cysts/masses measured >8.0 cm and were found in older women (>40 years of age), except for germ cell tumors, which were found in younger patients (6–15 years).

Nonneoplastic cysts

Of the total 26 histologically proven cases, cytology yielded positive results in 17 cases whereas nine cases were diagnosed as false negative due to the presence of nonspecific findings, such as the presence of histocytes and degenerated cells, and were cytologically categorized as benign cyst contents not otherwise specified.

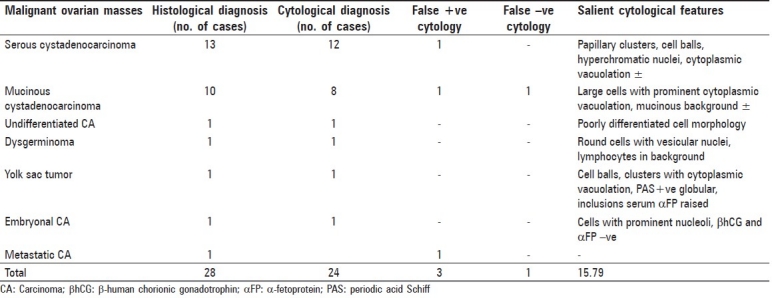

The aspirate from follicular cysts [Figure 1] consisted of granulosa cells with round nuclei and scanty cytoplasm against a bloody background or may be against a clear proteinaceous background, as also reported by Nunez et al.[9]

Figure 1.

Follicular cyst; benign cells with round nuclei and scanty cytoplasm against a bloody background (Pap ×200)

The aspirate from luteal cysts comprised of large round cells with abundant foamy or granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and ill-defined cell borders with small, vesicular nuclei, similar to the observation of Moran et al.[10] and Ganjei et al.[11]

Smears of endometriotic cysts showed hemosiderin-laden macrophages against a background of hemolysed blood.

Benign neoplasms

Despite the widespread use of sonography and laparoscopy, the diagnosis often remains uncertain due to difficulty in differentiating between a unilocular simple cystadenoma and a follicular or corpus luteum cyst of the ovary. In the benign category, using the established cytomorphologic criteria, subclassification into benign neoplastic and nonneoplastic cysts is also difficult. This distinction is of clinical importance because the former requires operative treatment while the latter may be treated by aspiration alone.[12]

Serous cystadenoma

Of the 38 cases, eight cases proved to be false negative mainly due to scanty and degenerated cell material, especially in simple serous cysts with atrophic lining, posing a diagnostic challenge, as also reported by Ganjei et al.[11] and Kruezer et al.[13] In 30 diagnosed cases, cytology revealed loose aggregates of benign epithelial cells with uniform round nuclei, consistent with Ramzy et al.[3]

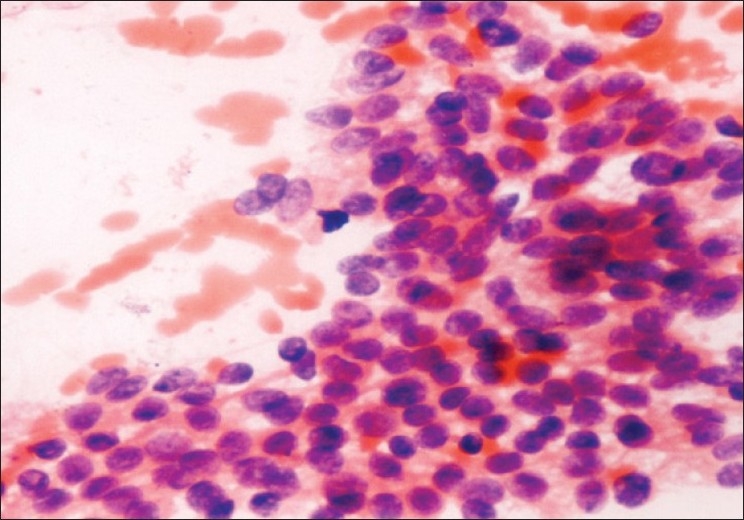

Mucinous cystadenoma

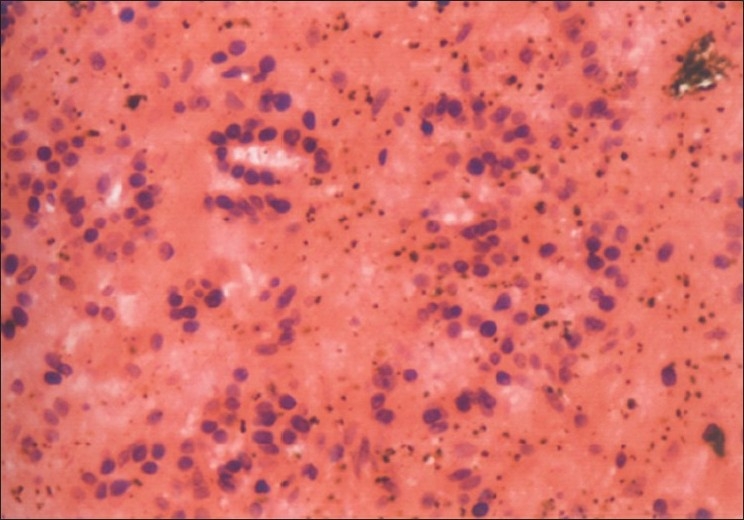

In 12 diagnosed cases, cytology showed sheets of benign cells with vacuoles, pushing the nucleus to the periphery [Figure 2]. Four cases proved to be false negative due to the presence of thick mucoid material obscuring the cellular details, similar to the findings of Higgins et al.[14] Two cases were incorrectly labeled as mucinous cystadenocarcinoma due to the presence of small glandular clusters and cell balls, giving the impression of multilayering. However, a similar confusing situation has also been observed by Roy et al.[15]

Figure 2.

Mucinous cystadenoma; sheets of benign epithelial cells with uniform nuclei and cytoplasmic vacuolation (Pap ×400)

Benign cystic teratoma

The aspirate of four diagnosed cases showed keratinized sheets and/or anucleate squames against a thick greasy background [Figure 3] similar to the findings of Orell et al.[16] In two cases, only necrotic debris and degenerated cells were seen and therefore no opinion could be made.

Figure 3.

Benign cystic teratoma; benign squamous cells against a dirty background of keratinous debris (Pap ×400)

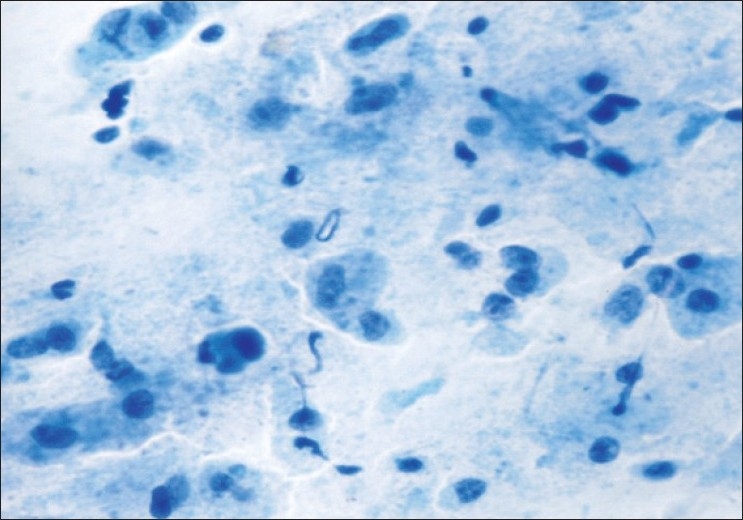

Granulosa cell tumor

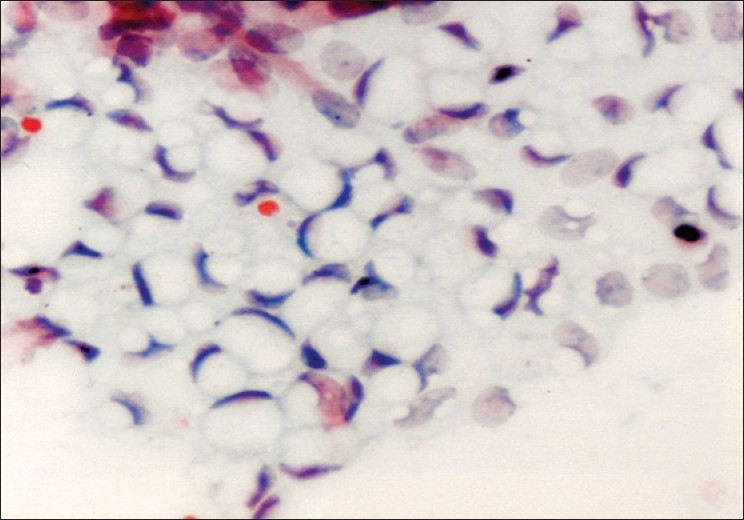

Cytology showed clusters of medium-sized cells with round to ovoid monomorphic nuclei and finely granular chromatin [Figure 4]. Nuclear grooves were present in some but not all the cells, similar to Ehya et al.[17] Imprints showed classical Call-Exner bodies. One case was misdiagnosed as undifferentiated CA due to the presence of acinar arrangement and nuclear atypia.

Figure 4.

Granulosa cell tumor; monomorphic cells and nuclei with finely granular chromatin (Pap ×200)

Thecoma fibroma

A single diagnosed case showed moderate cellularity comprising of oval to spindle cells with scanty cytoplasm, finely granular chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli, similar to the findings of Yang et al.[18]

Malignant ovarian neoplasms

Table 2 shows cytohistological correlation of malignant cysts and salient cytological features. There were three false-positive cases in the malignant category, one case each of borderline serous cystadenocarcinoma, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma and metastatic carcinoma, all falsely interpretated as serous cystadenocarcinoma, while one case was wrongly diagnosed as mucinous cystadenoma owing to the lack of clear-cut malignant features and abundant mucin in the background.

Thus, the sensitivity and specificity of cytology in the diagnosis of a variety of ovarian masses was 79.2% and 90.6%, respectively. Ganjei et al.[11] and Roy et al.,[15] in their study, described sensitivity and specificity of cytology in diagnosis of ovarian lesions as 94.2%, 91.4% and 75% and 100%, respectively. The overall diagnostic accuracy in this study was 89.9%, compared to an overall diagnostic accuracy of 96% described by Moran et al.[10]

Conclusions

-

(1)

Aspiration cytology can provide useful information in young women with functional cysts of the ovary to avoid an unnecessary operation.

-

(2)

Acellular fluid should not be considered nondiagnostic, because it represents benign cysts in a majority of the cases.

-

(3)

False-negative results of FNAC in ovarian cystic lesions are usually due to the low cellularity of the sample and secondary degenerative changes.

-

(4)

The distinction between cystadenocarcinoma and tumors of a low malignant potential cannot be confidently made by cytology alone.

-

(5)

Diagnostic accuracy will improve if size of the lesion is considered.

-

(6)

Clinical examination, pelvic ultrasound and FNAC were complementary and none of the methods was diagnostic by themselves. However, USG-guided FNAC of ovarian cyst is an easy, fairly sensitive and specific outdoor technique and should be employed as a routine, especially in benign ovarian cysts, to avoid superfluous surgery. Therefore, all clinical (age, menopausal status, ascites) and sonographic (cyst size, bilaterality, complexity, etc.) findings should be considered in collaboration with FNAC findings before arriving at a diagnosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Sevin BU, Greening SE, Nadji M, Ng AB, Averette HL, Nordquist SR. Fine needle aspiration cytology in gynecologic oncology: I: Clinical aspects. Acta Cytol. 1979;293:277–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selvaggi SM. Cytology of non-neoplastic cysts of the ovary. Diagn Cytopathol. 1990;6:77–85. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840060202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramzy I, Martinez SC, Schantz HD. Ovarian cysts and masses: Diagnosis using fine needle aspirations. Cancer Detect Prev. 1981;4:493–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajdu SI, Melamed MR. Limitations of aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of primary neoplasms. Acta Cytol. 1984;28:337–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sevelda P. Presented at the First European Congress of Gynecologic Endoscopy. France: Clermont-Ferrand; 1992. Sep 9-11, Prognostic influence of intraoperative rupture of malignant ovarian tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wojcik EM, Selvaggi SM. Fine needle aspiration cytology of cystic ovarian lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;11:9–14. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840110104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dordoni D, Zaglio S, Zucca S, Favalli G. The role of sonographically guided aspiration in the clinical management of ovarian cysts. J Ultrasound Med. 1993;12:27–31. doi: 10.7863/jum.1993.12.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geier GR, Strecker JR. Aspiration Cytology and E2 content in ovarian tumors. Acta Cytol. 1981;25:400–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nunez C, Diaz JI. Ovarian follicular cysts: A potential source of false - positive diagnoses in ovarian cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 1992;8:532–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840080515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moran O, Menczer J, Gijlad BB, Lipitz S, Goor E. Cytologic examination of ovarian cyst fluid for the distinction between benign and malignant tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:444–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganjei P, Dickinson B, Harrison TA, Nassiri M, Lu Y. Aspiration cytology of neoplastic and non-neoplasic ovarian cysts: Is it accurate? Int J Pathol. 1996;15:94–101. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199604000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stastny J, Johnson DE, Frable WF. Fine needle aspiration of non-neoplastic and neoplastic ovarian lesions. Acta Cytol. 1992;36:611. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruezer GE, Paradowski T, Wurche KD, Flenker H. Neoplastic or non-neoplastic ovarian cyst. The role of cytology? Acta Cytol. 1995;39:882–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins RV, Matkins JF, Morroum MC. Comparison of fine needle aspiration cytoloic findings of ovarian cysts with ovarian histologic findings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:550–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy M, Bhattacharya A, Roy A, Sanyal S, Sangal MK, Dasgupta S, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology of ovarian neoplasms. J Cytol. 2003;20:31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orell SR, Sterrett GF, Walters MN, Whitaker D. In: Fine needle aspiration cytology. 3rd ed. Edinburgh London: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. Male and female genital organs; pp. 362–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehya H, Lang WR. Cytology of granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. Am J Clin Pathol. 1986;85:402–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/85.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang GC, Mesia AF. FNAC of fibrothecoma of the ovary. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;22:284–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199910)21:4<284::aid-dc11>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]