Abstract

Besides peripheral blood smears, microfilariae have been described in aspirate smears from different sites. Identification of microfilariae in the chylous urine of otherwise asymptomatic filarial patients has been rarely described. One such case is presented.

Keywords: Mirofilaria, urine, chyluria

Introduction

Filariasis can have several manifestations, chyluria and tropical pulmonary eosinophilia being the unusual manifestations reported mainly from South Asian countries. Chyluria is a state of chronic lymphourinary reflux via fistulous communications secondary to lymphatic stasis caused by obstruction of the lymphatic flow. Detection of microfilariae in the sediment smears of urine has been described in the cystoscopically catheterized urine[1] but very rarely in the normally voided urine sample,[2] especially the chylous urine.

Case Report

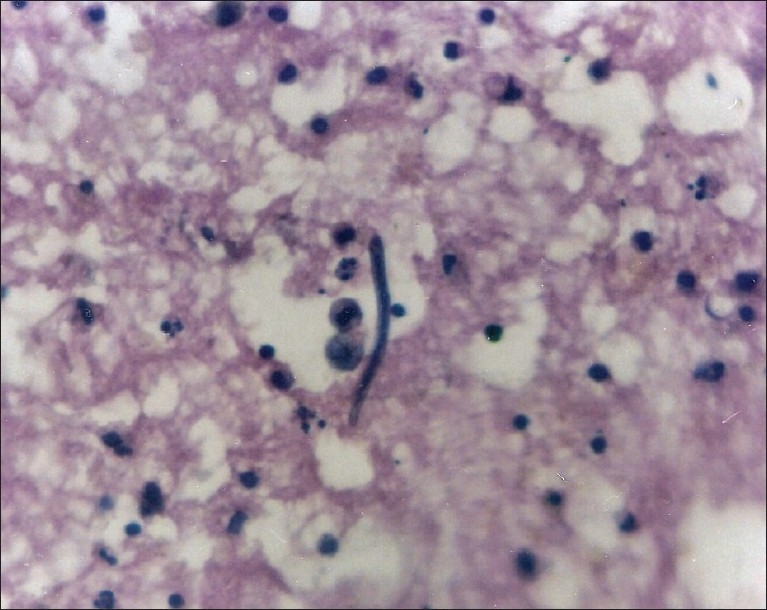

A 25-year-old man from the eastern part of India presented with complaints of passage of white urine intermittently since the last two months. He had no other complaint. His physical examination was within normal limits. On investigations, his hemoglobin was 11 g/dl, total leukocyte count (TLC) of 8600/cmm, and a differential of, polymorphs 70%, lymphocytes 25% and eosinophils 5%. Peripheral blood smears were unremarkable, with no parasites. He was asked to collect the urine sample when it was white. Examination of the urine was performed. Its color was milky-white and it did not clear on heating with 10% acetic acid, but cleared when mixed with equal parts of ether and on being shaken vigorously. Urinary protein was two plus (++) and no sugar was detected. Smears prepared from urinary deposits were fixed in 95% ethanol, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E). The smears showed sheathed motile microfilariae having a uniformly tapering caudal end with no terminal nuclei. Occasional lymphocytes and rare red blood cells were also seen [Figure 1]. A diagnosis of chyluria with Wuchereria bancrofti microfilaruria was made.

Figure 1.

Microfilaria in urine sediment (H and E, ×400)

Discussion

Filariasis is a global problem. Numerically, the public health problem of lymphatic filariasis is greatest in India, China and Indonesia. These three countries account for approximately two-thirds of the estimated world total of persons infected. In the endemic areas, up to 10% may be afflicted by filariasis.[3] In India, lymphatic filariasis is mainly caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, the vector for which is the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus (C. fatigans).

Besides peripheral blood smears, microfilariae have been reported in cervicovaginal smears, bronchial washings, ovarian cyst fluid,[2] hydrocele fluid, pericardial fluid, synovial fluid, nipple discharge, bone marrow smears[4] and aspirates from breast, lymph nodes, thyroid,[5] ovary, liver and spleen.[6] Microfilariae (MF) have also been rarely described in routine cytology smears of benign and malignant tumors.[7]

Chyluria occurs only in 2% of filarial afflicted patients in the filarial belt. The adult filarial worm causes lymphangitis, lymphatic hypertension and valvular incompetence. If the obstruction is between the intestinal lacteals and thoracic duct, the resulting cavernous malformation opens into the urinary system forming a lymphourinary fistula. The common sites of the fistula are renal fornix, pelvicalyceal system of the kidney, trigone of the bladder and prostatic urethra. Once such a fistula is formed, intermittent or continuous chyluria occurs. In addition to malnutrition caused by proteinuria, the patient may also present with renal colic due to chylous clots resulting in acute urinary retention, although this is rare.

Milky urine is also produced by urates, which clear on heating or phosphates, which clear on adding 10% acetic acid. Other causes of chyluria may be parasitic (Wuchereria bancrofti, Eustrongylus gigas, Tenia echinococcus, Tenia nana, malarial parasites, Cereonomas hominis) or nonparasitic (congenital lymphangiomas of the urinary tract, tuberculosis, reteroperitioneal abscess and neoplastic infiltration of retroperitional lymphatics, trauma and pregnancy). By far, the most important and the most common cause–effect relationship of chyluria is the one with Wuchereria bancrofti.

The most useful roentgenographic procedure in delineating lymphatic channels in patients of chyluria is lymphangiography, which is diagnostic to visualize the lymphourinary fistula, particularly when surgical intervention is planned. In some studies, radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy has been claimed to be a noninvasive technique in the diagnosis and management of chyluria.

In view of the rarity of detection of microfilariae in the urine as well as blood samples of even overt filariasis patients, serological markers have been developed to detect filarial infection. It is now known that patients with Wuchereria bancrofti infection mount an immune response of immunoglobulin of G4 subclass against Wuchereria bancrofti antigen, Wb-SXP-1. Rao et al.[8] used antibodies specific to the recombinant filarial antigen, Wb-SXP-1, to develop a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of circulating filarial antigen in sera from patients with lymphatic filariasis caused by Wuchereria bancrofti. This test was found to be 100% sensitive for the Wuchereria bancrofti infection. A similar ELISA that detects filaria-specific immunoglobulin G4 antibodies in unconcentrated urine has been developed by Itoh et al.[9] Similarly, estimation of urinary and serum immune complexes (ICs) are also potential serological markers for both the differential diagnosis of filarial infection and the therapeutic monitoring of MF carriers. In fact, occurrence of filaria-specific ICs in urine and their passage through the filtering structures of the kidney is suggestive of the focal or diffuse damage in those subjects. Detection of ICs in urine may provide a noninvasive means of assessing the extent of renal damage in patients with lymphatic filariasis.[10]

The management of cases of chyluria includes bed rest, high protein diet exclusive of all fats (except medium chain triglycerides, which enter the circulation through the portal system by-passing the thoracic duct), drug treatment (diethycarbamazine) and use of abdominal binders, which is claimed to prevent the lymphourinary reflux by increasing the intra-abdominal pressure. Surgical management is indicated in cases of recurrent clot-colic, retention of urine and progressive weight loss despite conservative treatment, especially in children. The cornerstone of management of chyluria is renal pelvic instillation sclerotherapy. Surgical alternatives include open or laparocopic chylolymphatic disconnection.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Webber CA, Eveland LK. Cytologic detection of Wuchereria bancrofti microfilariae in urine collected during a routine workup for hematuria. Acta Cytol. 1982;26:837–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter A, Krishnaswami H, Cariappa A. Microfilariae of Wuchereria bancrofti in cytologic smears. Acta Cytol. 1983;27:432–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diamond E, Schapira HE. Chyluria-a review of the literature. Urology. 1985;26:427–31. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma S, Rawat A, Chowhan A. Microfilariae in bone marrow aspiration smears, correlation with marrow hypoplasia: a report of six cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2006;49:566–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varghese R, Raghuveer CV, Pai MR, Bansal R. Microfilariae in cytologic smears: a report of six cases. Acta Cytol. 1996;40:299–301. doi: 10.1159/000333755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhaskaran CS, Rao KV, Prasantha-Murthy D. Microfilarial granuloma of the spleen. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1975;18:80–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta S, Sodhani P, Jain S, Kumar N. Microfilariae in association with neoplastic lesions: report of five cases. Cytopathology. 2001;12:120–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.2001.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao KV, Eswaran M, Ravi V, Gnanasekhar B, Narayanan RB, Kaliraj P, et al. The Wuchereria bancrofti orthologue of brugia malayi SXP1 and the diagnosis of bancroftian filariasis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;107:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itoh M, Weerasooriya MV, Qiu G, Gunawardena NK, Anantaphruti MT, Tesana S, et al. Sensitive and specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the diagnosis of Wuchereria bancrofti infection in urine samples. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:362–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixit V, Subhadra AV, Bisen PS, Harinath BC, Prasad GB. Antigen-specific immune complexes in urine of patients with lymphatic filariasis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2007;21:46–8. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]