Abstract

Eosinophilic granuloma is a variety of histiocytosis-X with unknown etiology. Eosinophilic granuloma occurs as single or multiple lesions of bone destruction. It is seen more commonly in children or young adults although it may be found at all ages. Other sites like the lung and the gastrointestinal tract may also be affected. This is a rare case of eosinophilic granuloma which presented as frontal headache. The radiographic and cytological findings were characteristic of the disease.

Keywords: Aspiration cytology, eosinophilic granuloma, headache

Introduction

Eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is the benign form of three clinical variants of langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). The other two variants are Letterer-Siwe disease and Hand-Schüller-Christian disease. The term, “eosinophilic granuloma” was first introduced by Lichtenstein and Jaffe in 1940.[1] EG is characterised by single or multiple skeletal lesions, and predominantly affects children, adolescents, and young adults. Solitary lesions are more common than multiple lesions. When multiple lesions occur, the new osseous lesions appear within one or two years. Any bone can be involved; the more common sites include the skull, mandible, spine, ribs, and the long bones.[2–4] Symptoms include localised pain, tenderness, swelling, fever, and leukocytosis. Lesions usually begin to regress after approximately three months, but they may take as long as two years to resolve. EG has got a good prognosis and may spontaneously regress; it is extremely radiosensitive.[5] We present one such case that presented with frontal headache and was diagnosed on fine needle aspiration cytology.

Case Report

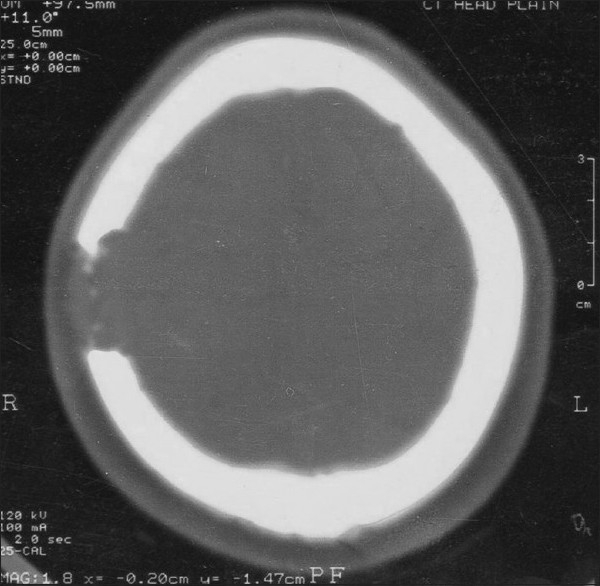

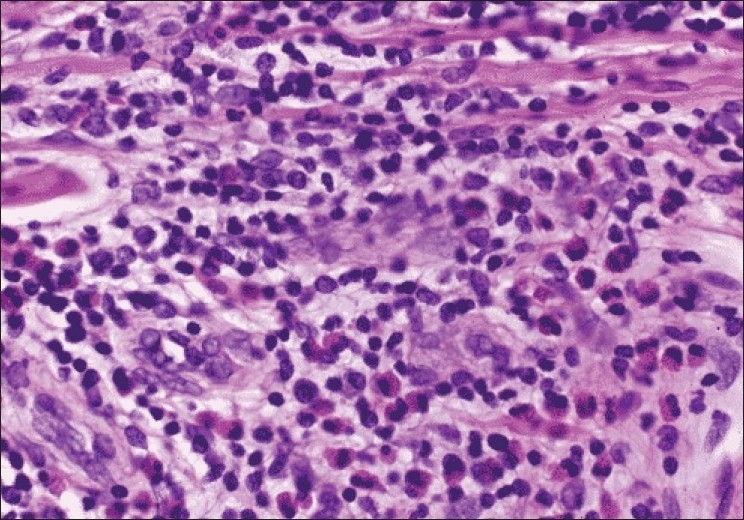

A female aged 36 years presented to the Department of Medicine with complaint of headache. The pain felt was localised in the frontal area of the skull, and had been dull and continuous in nature for the last two months. On palpation, a swelling was felt in the frontal region of the skull which was soft in consistency, and there was minimal tenderness over the swelling. The bone seemed to give way in the centre. There was no history of trauma or vomiting associated with the headache. The results of the hematological investigations were within normal limits. Skull radiograph revealed a single punched out area of bone destruction with sharp margins in the parietal region. A chest radiograph and ultrasonography of the abdomen did not reveal any abnormality. Axial computed tomography (CT) sections of the cranium showed an osteolytic lesion in the parietal bone on the right side with a small intact bony fragment in the centre (button sequestrum). Inner and outer tables of the skull were eroded [Figure 1]. Fine needle aspiration of the lesion revealed both sheets of and isolated eosinophils intermixed with macrophages and giant cells. Macrophages contained ingested debris and red blood cells [Figure 2]. Eosinophilic granuloma of the frontal bone was diagnosed on the basis of cytological and radiological findings.

Figure 1.

Axial CT scan sections of the cranium on bone window showing osteolytic lesion in the parietal bone on the right side

Figure 2.

Microphotograph showing macrophages with ingested debris in a background of eosinophils and red blood cells (Giemsa, ×400)

Discussion

Eosinophilic granuloma is a benign disorder that affects children and young adults, particularly males. Solitary EG accounts for the majority of LCH cases, usually involving bone and less commonly the lymph nodes, lung or skin.[6] The solitary bone lesion may be asymptomatic, or it may cause bone pain because of the expansion of the medullary bone; pathological fractures may ensue.[2,7] The distinctive morphological lesions of the entire group of Langerhans histiocytosis disorders consist of expanding erosive accumulations of histiocytes, usually within the medullary cavity.

The clinical and radiographic findings are often not specific enough to determine the diagnosis. Cytology is very helpful in arriving at the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma of the bone.[6] Morphologically the key feature is the identification of Langerhans cells with characteristic grooved, folded, indented nuclei in the appropriate milieu that includes variable numbers of eosinophils and histiocytes including multinucleated forms, often appearing similar to osteoclasts or touton like giant cells, neutrophils and small lymphocytes.[6,8] The concentration of the eosinophilic infiltrate varies from scattered mature cells to sheet-like masses of cells. Occasionally, areas of bone necrosis may interrupt the cellular infiltrate. The foamy cells may also be amassed in clumps, which are of no clinical significance because these clumps represent phagocytosis of lipid debris.

Any bone can be involved. The skull, long bones of the upper extremities and the flat bones are affected in descending order of frequency.[6] Solitary lesions are more common than multiple ones. When the lesions are multiple, new osseous lesions occur within one or two years but the condition is still classified as EG. Radiologists need to be aware that additional EG of the bone occurring as long as four years after initial diagnosis, should be interpreted as a localised form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. This differentiation is important because the prognosis is more favourable with focal disease with multifocal disseminated disease, which involves organs other than the skeletal system. Similar lesions may occur within the lungs, skin, and stomach, either as a unifocal lesion or as part of multifocal disease. Lung involvement occurs in 20% of the patients with EG and in an older group (age, 20–40 years). Lung involvement has a strong association with smoking. Diffuse pulmonary infiltrates may be a manifestation of a covert osseous EG.[5] In 50–75% of the patients, the disease is monostotic and skull involvement is seen in 50% of the patients. The disease has the ability to regress spontaneously and is significantly radiosensitive. The prognosis of eosinophilic granuloma has been found to be good.[9]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Lichtenstein L, Jeffe HL. Eosinophilic granuloma of bone: With report of a case. Am J Pathol. 1940;16:595–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azouz EM, Saigal G, Rodriguez MM, Podda A. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis: pathology, imaging and treatment of skeletal involvement. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:103–15. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haouimi AS, Al-Hawsawi ZM, Jameel AN. Unusual location of eosinophilic granuloma. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1489–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park SH, Park J, Hwang JH, Hwang SK, Hamm IS, Park YM. Eosinophilic granuloma of the skull: a retrospective analysis. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2007;43:97–101. doi: 10.1159/000098380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang JT, Chang CN, Lui TN, Ho YS. Eosinophilic granuloma of the skull-report of four cases. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1993;16:257–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain A, Alam K, Maheshwari V, Jain V, Khan R. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the ulna: Diagnosis on fine needle aspiration cytology. J Cytol. 2008;25:153–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greis PE, Hankin FM. Eosinophilic granuloma.The management of solitary lesions of bone. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;257:204–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukhopadhyay S, Mitra PK, Ghosh S. Touton like giant cell in lymph node in a case of langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Cytol. 2007;24:191–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howarth DM, Gilchrist GS, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Edmonson JH, Schomberg PJ. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Diagnosis, management and outcome. Cancer. 1999;85:2278–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990515)85:10<2278::aid-cncr25>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]