Abstract

Background:

Parapharyngeal tumors are rare and often pose diagnostic difficulties due to their location and plethora of presentations.

Objectives:

The study was undertaken to study the occurrence in the population and to evaluate the exact nature by fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC).

Materials and Methods:

A total of five hundred and six cases of lateral neck lesions were studied over three and half years. Of these 56 suspected parapharyngeal masses were selected by clinical and radiological methods. Cytopathology evaluation was done by fine needle aspiration cytology with computed tomography and ultrasonography guidance wherever necessary. Histopathology confirmation was available in all the cases.

Results:

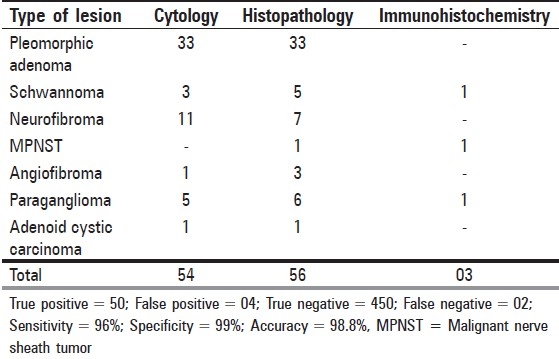

On FNAC diagnosis could be established in 54 cases while in two cases the material was insufficient to establish a diagnosis. The tumors encountered were, pleomorphic adenoma (33), schwannoma (3), neurofibroma (11), paraganglioma (5), angiofibroma (1) and adenoid cystic carcinoma (1). Four false positives and two false negative cases were encountered. Overall sensitivity was 96%, with specificity of 99% and accuracy being 98.8%.

Conclusions:

With proper clinical and radiological assessment, FNAC can be extremely useful in diagnosing most of these lesions except a few which need histopathological and even immunohistochemical confirmation.

Keywords: Parapharyngeal space tumors, paraganglioma, fine needle aspiration cytology

Introduction

Parapharyngeal space (PPS) is a rare location for head and neck tumors.[1] It is a space in the suprahyoid neck that contains fat and is surrounded by several other spaces defined by the fascial layers of neck.[2] The tumors are mostly benign and account for 0.5% tumors of head and neck.[3] Pleomorphic salivary adenoma (arising from deep lobe of parotid), malignant tumors of salivary gland, (for example, adenoid cystic carcinoma), carotid body tumors, angiofibroma, schwanomma, neurofibromas, ameloblastomas, rarely meningioma and chordoma are commonly encountered lesions.[4]

The patients usually present with swelling of two specific sites namely oropharynx and lateral neck (cervical or submandibular mass), there may be oral cavity bulge, serous otitis, headache, syncope or even cranial nerve palsies involving vagus and hypoglossal nerves, leading to disorders of swallowing or speech.[5]

The diagnosis is done by physical examination, radiological imaging, and pathological examination. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) can be an easy, rapid, and effective method of diagnosing these myriad of lesions of a specific anatomic space, though some gray zones prevail.[6] Diagnostic difficulty persists due to their similar mode of presentations and at times morphological overlap. Hence, some cases can only be confirmed by histopathological examination and some by immunohistochemistry.

As these tumors are rare and often pose diagnostic difficulties the authors have selected few cases to study the occurrence in our population, to evaluate the exact nature by cytological study and final confirmation by histopathology and immunohistochemistry if required. It is very important to diagnose the nature of tumor whether benign or malignant prior to therapy, because treatment protocol is variable and early diagnosis can give better survival rate.

Materials and Methods

A total of five hundred and six cases of lateral neck lesions were studied by initial screening during January 2004 to August 2007. Out of these, 56 (11%) suspected parapharyngeal masses were selected by clinical and radiological methods. Cytomorphological patterns were evaluated by doing FNAC with 10 cc syringe and 22 gauge / 24 gauge needle following the standard procedure.[7] Fine needle aspiration was also done under guidance (Computed tomography/ ultrasonography) as and when necessary.

Confirmation was done by histopathology (routine hematoxylin and eosin stain) and immunohistochemistry on paraffin sections in selected cases (by LSAB technique). Cytology staining was done by hematoxylin and eosin (wet smears) and Leishman-Giemsa (dry smears).

Results

Total fifty six cases of parapharyngeal space tumors were selected, of which forty eight were benign (86%), while only eight malignant tumors (14%) have been studied. The age ranged from 14 to 70 years with maximum predilection in the fourth decade. Male:Female ratio was 1:1.

Out of 56 cases, 54 gave a satisfactory cytological material; in one of the paraganliomas only blood was aspirated, whereas out of three angiofibromas cellularity was very scanty even on repeated aspirations in one case.

Pleomorphic salivary adenoma (59%) showed maximum incidence in the benign group, followed by neurofibroma (12%), and schwanomma (9%)[Table 1].

Table 1.

Correlation of cytopathology with histopathology and immunohistochemistry

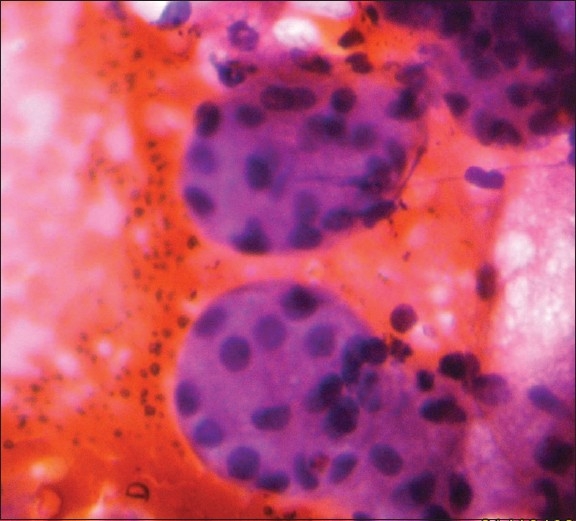

In the malignant group of PPS neoplasms, paragangliomas showed highest incidence (11%) followed by malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) and adenoid cystic carcinomas (2%) each[Table 1]. Histopathological confirmation of paraganliomas was done after cytological detection[Figure 1]. Finally immunohistochemical confirmation was done in one case.

Figure 1.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology of paraganglioma (H and E, × 100)

Discussion

Parapharyngeal space tumors are difficult to diagnose early due to their location and plethora of presentation, they are usually benign, pleomorphic adenoma arising from the deep lobe of parotid has been found to be the most common tumor of parapharyngeal region by several authors[8] and also by us. Studies have shown that there is no difference in the prognosis of pleomorphic adenomas even if they are cellular and show cytologic atypia in the form of scattered hyperchromatic nuclei.[9] Though this study was not aimed to prognosticate these tumors, we found one such case which definitely needed histopathological confirmation.

We found only one case of adenoid cystic carcinoma (2%). It has been found to be the most common malignant tumor of minor salivary gland by Spiro et al.[10] This tumor has a worse prognosis due to its anatomic site and higher stage at presentation.

Neurofibromas and schwannomas are rather common tumors of parapharyngeal space.[8] But their occurrence at this site, slow growth, and associated neurological manifestations can mimic other entities.[11] Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor is rare at this site and has grave prognosis.[12] Neurogenic tumors comprised (both benign and malignant) only 23% in this series in contrast to others.[1]

The paragangliomas occurring in head and neck comprise 3% of all parangangliomas and almost all located in the parapharyngeal space and arise in carotid body.[13] Most follow a benign course, but may be malignant. Paragangliomas may be bilateral, multicentric or may be a component of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome. We found two cases of paraganglioma occurring in the same family. Whether these were the component of the MEN syndrome could not be established as the family was lost to follow up. All our cases needed histopathological confirmation and immunohistochemistry in one.

Angiofibromas can also arise in this site,[14] but we failed to diagnose them on cytology alone and most of these smears were grossly hemorrhagic with few spindle cells only. The solitary case of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor and one cellular schwannoma needed both histopathological and immunohistochemical confirmation.

Cytological diagnosis was almost corroborative with final histopathological diagnosis in all cases with very few exceptions. True positive cases comprised 50 (89%), whereas there were only two false negative cases due to paucity of materials or difficulty in approaching the lesions. Thus, diagnostic accuracy in this series was approximately 98.8% with only four false positive reports. Therefore, sensitivity in this study was 96% and specificity 99%, which corroborated with the findings of earlier studies.[15]

Parapharyngeal masses sometimes fail to be detected early due to their location and overlapping symptoms with other common illnesses. Their importance lies in the fact that even benign lesions, if left untreated, may be fatal due to encroachment of vital structures. Clinical examination alone may not be sufficient to diagnose a mass or parapharyngeal lesion. With proper clinical and radiological assessment, FNAC can be extremely useful in diagnosing most of these lesions except a few which need histopathological and even immunohistochemical confirmation.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the technical staff of the respective departments for giving us necessary support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Luna-Ortiz K, Navarrte-Aleman JE, Granados-Gracia M, Herrea-Gomez A. Primary parapharyngeal space tumors in Mexican cancer center. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005:587–91. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stambuk HE, Patel SG. Imaging of the parapharyngeal space. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008:77–101. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez Ferro M, Fernandez Sanroman J, Costas Lopez A, Sandoval Gutierrez J, Lopez de Sanchez A. Surgical treatment of benign parapharyngeal space tumors: Presentation of two clinical cases and revision of literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008:61–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu W, Strawitz JG. Parapharyngeal growth of parotid tumor: Report of two cases. Arch Surg. 1977:709–11. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1977.01370060041006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhi KO, Ren WH, Zhang L, Wen YM, Zhang YC. Diagnosis and surgical approach of parapharyngeal space neoplasms. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue. 2007:547–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mondol A, Raychoudhury BK. Peroral fine needle aspiration cytology of parapharyngeal lesions. Acta Cytol. 1993:694–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orell SR, Sterrett GF, Whitaker D. Techniques of FNA cytology. In: Orell SR, Sterrett GF, Whitaker D, editors. Fine needle aspiration cytology. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed F, Waqar-Uddin, Khan MY, Khawar A, Bangush W, Aslam J. Management of parapharyngeal space tumors. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2006:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thunnissen FB, Peterse JL, Buchholtz R, Van der Beek JM, Bosman FT. Polyploidy in pleomorphic adenomas with cytologic atypia. Cytopathology. 1992:101–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.1992.tb00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiro RH, Huvos AG, Strong EW. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary gland: A clinicopathologic study of 242 cases. Am J Surg. 1974:512–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(74)90265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szmeja Z, Sefter W, Szymice E, Wierzbicka M, Zdanowicz E. Neurofibroma of the parapharyngeal space: A case report. Otolaryngol Pol. 1998:215–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graccion JG, Enzinger FM. Malignant schwannoma associated with von recklinghausen’ neurofibromatosis. Virchows Arch (A) 1979:43–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00427009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lack E. Washington DC: Fasc 19; 1997. Tumors of adrenal gland and extra adrenal paraganglioma: Atlas of tumor pathology. Series 3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hibbert J, editor. Scott-Brown's otolaryngology. 6th ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005. Laryngology and Head and Neck Surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mondol A, Gupta S. The role of preoral fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the diagnosis of parapharyngeal lesions: A study of 51 cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1993:253–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]