Abstract

This study examines variation of morphologic features, including emperipolesis, during the evolution of a case of Rosai Dorfman Disease (RDD). A 44-year-old male patient with RDD affecting the salivary glands, cervical lymph nodes, nasal and maxillary sinus mucosa had a waxing and waning course over two and a half years, with episodic sudden increase in size followed by involution and then a static course with moderate sized swellings. Multiple aspirations and biopsies were performed, which form the basis of this study. Four classical cases of RDD on aspirates and another four on biopsy were analyzed for comparison, with quantification of the number of lymphocytes engulfed by histiocytes (emperipolesis). Three nasal biopsies and one salivary gland excision of the index case, performed during acute exacerbation, showed chronic inflammation and foamy histiocytes without emperipolesis, the aspirate showing emperipolesis nil in 45%, 1-3 lymphocytes in 15%, 4-10 in 36% and > 10 in 4%. Two aspirations and one lymph node biopsy done from static phase showed classical features of RDD with extensive emperipolesis, the aspirate from left cervical lymph node showing emperipolesis nil in 2%, 1-3 in 5%, 4-10 in 35% and > 10 in 58% while right cervical lymph node aspirate showed emperipolesis nil in 9%, 1-3 in 21%, 4-10 in 29% and > 10 in 41%. A biopsy performed from involuting cervical lymph node showed extensive apoptosis and vasculitis without foamy histiocytes or emperipolesis. For comparison, eight classical RDD cases showed abundant emperipolesis with mild variation. Emperipolesis is variable in RDD depending on disease activity, which has differential diagnostic relevance and demonstrates the natural history of this rare disease.

Keywords: Emperipolesis, lymphadenopathy, Rosai Dorfman disease, sinus histiocytosis

Introduction

Rosai Dorfman Disease (RDD) was originally called sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy when described by Rosai and Dorfman over 30 years ago.[1,2] This disease typically presents as massive but painless bilateral cervical lymph node enlargement accompanied sometimes by fever, in the first two decades of life. Leucocytosis, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia can be seen on investigation.[3] Microscopic examination of an affected lymph node shows dilated sinusoids packed with foamy histiocytes, which contain intact lymphocytes and/or plasma cells within their cytoplasm, termed emperipolesis. Histiocytes with emperipolesis are considered a constant feature of great diagnostic importance.[3] Biopsies showing foamy histiocytes without emperipolesis would therefore not merit a diagnosis of RDD.

The initial series describing the histopathologic spectrum remains the largest so far.[2] However, numerous reports of RDD affecting a variety of sites in the head and neck, intracranial, breast, gastrointestinal tract and other abdominal sites are available.[3] RDD of skin attracts a separate mention. Fine needle aspiration findings of RDD are well described[4] with the largest experience being from our institute.[5,6] Emperipolesis has always been described as the critical diagnostic feature of RDD in these cytology reports.

We report here an unusual case of RDD where a number of samples, both biopsy and fine needle aspirates, were obtained from the same patient at various intervals in the course of the disease. Microscopic findings varied at different periods of disease progression, serving as evidence for the morphological evolution process in RDD. The differential diagnostic implications of this variation are discussed.

Case Report

A 44-year-old male patient, a general medical practitioner by profession, presented with slowly progressive swelling of left submandibular gland for 10 years and cervical lymph nodes. The patient was a non-insulin-dependent diabetic, on treatment with oral hypoglycemics and insulin at different periods. He was operated upon with excision of the left submandibular gland. Histopathology report was chronic sialadenitis [Table 1, Specimen 1]. Patient continued to have enlarging cervical lymphadenopathy which would swell to three or four times the usual size over three to four days, accompanied by fever of around 38°C and rising blood sugar levels. Subsequently the nodes would regress to stable size over the next 10-15 days, with gradual subsidence of fever. Different lymph nodes were affected in each such episode. The patient also developed features of sinusitis over the next three months. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the head showed a left nasal mass and multiple cervical lymph nodes. Routine hemogram and serum biochemistry were normal except for the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which was raised at 62 mm in the first hour. Serum globulins were 4.1 g/dL.

Table 1.

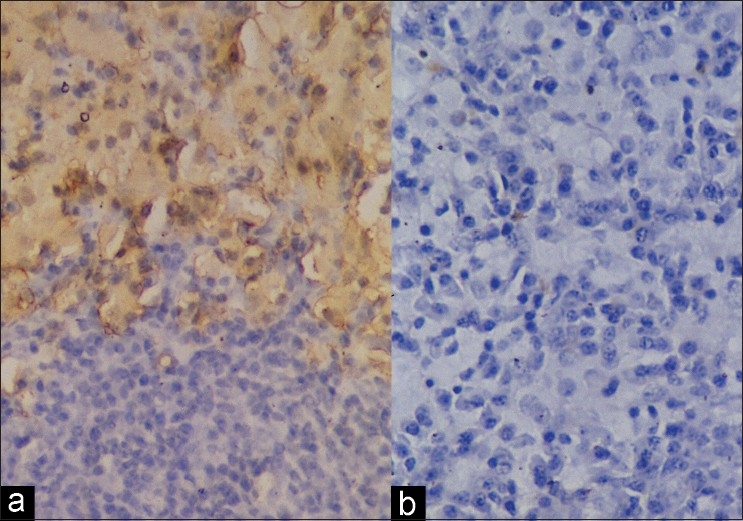

Details of biopsies and aspirations performed in sequential order, with clinical state at the time of biopsy, diagnosis rendered and the extent of emperipolesis seen within foamy histiocytes

The patient stabilized over the next three months with regression of nodes followed by a stable cervical lymphadenopathy. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of both left and right cervical stable nodes was performed, and reported as RDD [Table 1, Specimen 3]. Patient continued to have flare-ups with nasal mass causing obstruction, for which repeated excisions were performed. As detailed in Table 1, repeated biopsies were not diagnosed as RDD in view of absent emperipolesis and the possibility of rhinoscleroma was considered. However, special stains and culture studies were negative. Antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Since histopathology had always been performed during exacerbations and in one instance during involution, patient was kept on follow-up until he stabilized. Biopsy of a stable left cervical lymph node was performed, which yielded a diagnosis of RDD [Table 1, Specimen 8]. The patient continues to be on follow-up with similar complaints.

Materials and Methods

Tissue for histopathology was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and subjected to routine paraffin-embedded sections with Hematoxylin and Eosin staining. Special stains for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), periodic acid Schiff (PAS), Grocott's silver methanamine for fungus (Grocott), Perl's stain for iron, Van Kossa stain for calcium, Giemsa and modified Gram's stain for tissue sections were performed following standard protocols. Aspirations were performed using 10 ml syringe fitted on a syringe holder, using a 23-gauge needle, in an outpatient setting without anesthesia. Aspirates were smeared on glass slides and wet-fixed in 95% alcohol for Papanicolaou stain and air-dried for May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain, both stains being done in all aspirates. Extra smears for immunocytochemistry were similarly prepared and wet-fixed in 95% alcohol.

As a control group, four aspirates from cervical lymph nodes diagnosed as RDD were selected from the records of the cytopathology laboratory. Four biopsies, also diagnosed as RDD, including two from nasal mucosa and two from cervical lymph node were also included from the records of the pathology department as control cases. The clinical details and timing of biopsy/aspiration were not known. Since quantification of emperipolesis in RDD histiocytes has not been reported previously in the literature, this information was obtained as detailed below.

RDD histiocytes on aspirates were identified by abundant cytoplasm and large nuclei with nucleoli. Emperipolesis in these cells was quantified by counting the first 100 histiocytic cells fitting the above description in randomly selected fields. Fields were selected from the centre and tails of smears since larger cells aggregate near the tail. The number of lymphocytes or plasma cells clearly identified within these cells were enumerated. Cells were categorized into four groups based on extent of emperipolesis, yielding four groups: Nil, 1-3 lymphocytes/ plasma cells, 3-10 lymphocytes/ plasma cells and >10 lymphocytes/ plasma cells in a histiocyte. The percentage of these four groups was derived for each of these aspirates. Emperipolesis in biopsies was quantified in S100-positive histiocytes, using the same four categories as for cytology.

Immunocytochemistry for S100 was done using 1:100 dilution with overnight incubation. For CD 68 and Alpha-1-Antichymotrypsin (ACT) prediluted primary antibodies with one-hour incubation were used. Detection was done with Streptavidin Biotin method (LSAB2). All antibodies were obtained from Dako-Cytomation, Denmark.

Results

The specimens available from the patient in chronological order with date of sampling, phase of disease and quantification of the extent of emperipolesis in percentage are given in Table 1. The first specimen was left submandibular gland excision which was enlarged to four cm size. Microscopic examination showed foci of normal salivary gland and large areas of marked chronic sialadenitis with atrophy of salivary acini. The inflammatory infiltrate consisted of lymphocytes and plasma cells along with a few lymphoid follicles, fibrosis and focal necrosis. Areas showing foamy histiocytes with abundant foamy cytoplasm having indistinct cytoplasmic borders were seen. There was no emperipolesis. AFB, PAS, Grocott and Gram's stain were negative. This biopsy was interpreted as chronic sialadenitis.

The second biopsy from nasal mucosa was in multiple pieces. Most of the fragments showed marked chronic inflammation with lymphocytes and plasma cells. One of the pieces showed small collections of foamy histiocytes, negative with AFB, PAS, Giemsa, Perl's and Gram's stains. There was no emperipolesis. It was reported as chronic sinusitis.

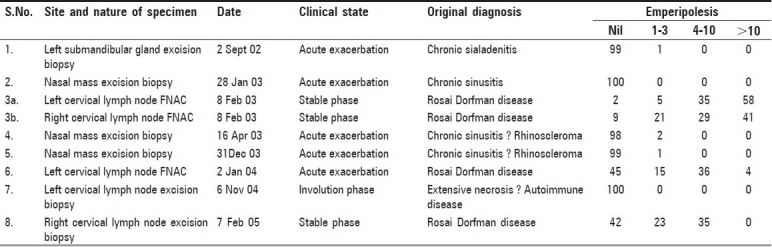

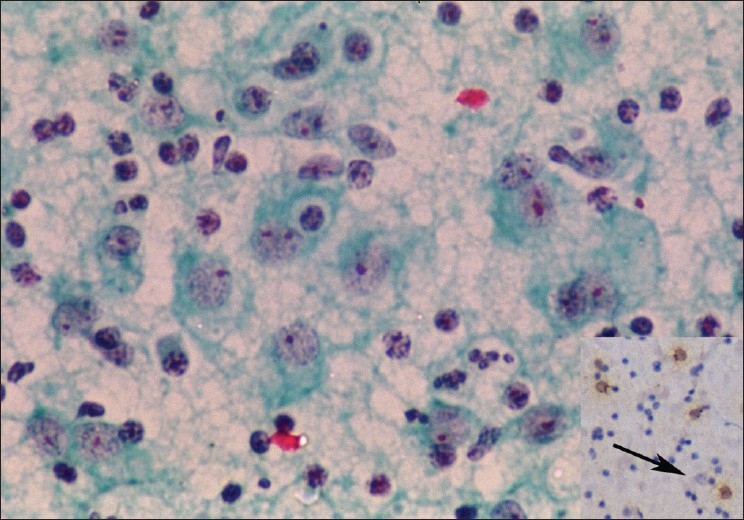

Third specimen was FNAC from right as well as left cervical lymph nodes. Both aspirates showed numerous large histiocytes with emperipolesis in a background of lymphocytes and plasma cells [Figure 1]. The histiocytes had abundant foamy cytoplasm and round nuclei with considerable variation in nuclear size and shape, some with prominent nucleoli. Emperipolesis was abundant with the entire cytoplasm being packed with lymphocytes and plasma cells. The diagnosis was RDD.

Figure 1.

Aspirate from left cervical lymph node in stable phase showing many large histiocytes with numerous lymphocytes and plasma cells packed within the cytoplasm (emperipolesis), obscuring the histiocyte nucleus. Occasional histiocytes in the background with less degree of emperipolesis are also seen (Papanicolaou, ×100)

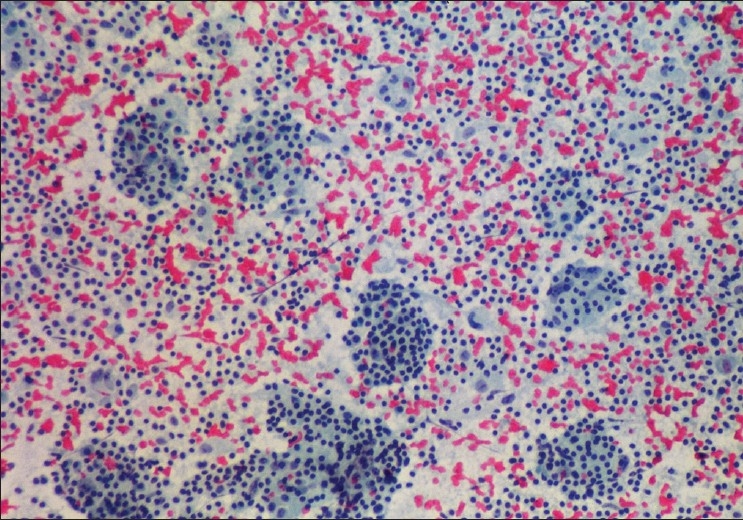

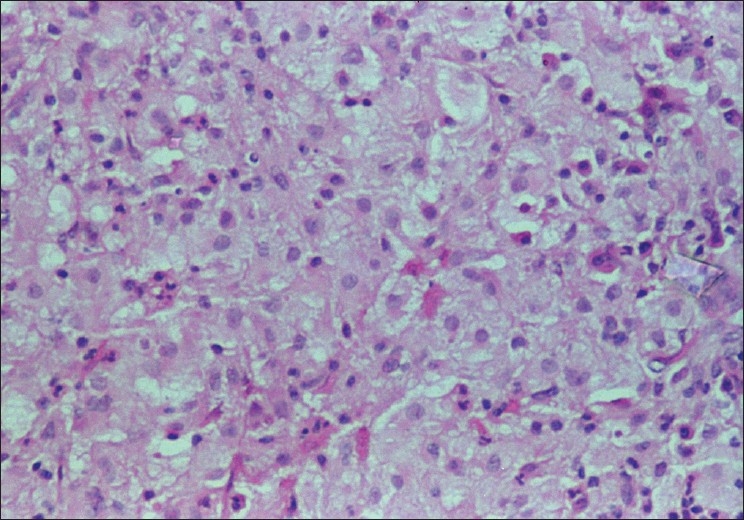

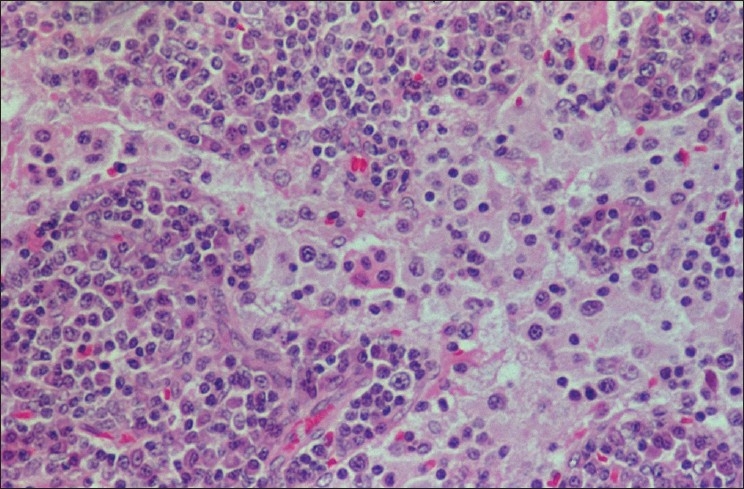

Fourth and fifth specimens were nasal mucosal excisions, received in multiple fragments showing chronic inflammation with extensive fibrosis and numerous foamy histiocytes [Figure 2]. Emperipolesis was not evident. Gram's, PAS and AFB stains were negative. Features were considered more likely to be rhinoscleroma than RDD. Immunocytochemistry for S100 was strongly positive in the cytoplasm and nuclei of the foamy histiocytes while CD 68 and ACT were negative [Figure 3]. Additional small histiocytic and mononuclear cells positive for CD68 and ACT were identified amongst the surrounding inflammatory cells.

Figure 2.

Biopsy from nasal mucosa during exacerbation, showing numerous foamy histiocytes. Definite emperipolesis is not evident (H and E, ×200)

Figure 3.

Biopsy from nasal mass in exacerbation showing S100 to be positive in foamy cells (a), while CD68 is negative (b). (Immunocytochemistry for S100 (a) and CD68 (b), ×200)

In view of discrepancy between cytology and histology, a repeat aspiration of left cervical lymph node was done when patient had exacerbation of symptoms. Aspirate showed numerous histiocytes with emperipolesis, although to a lesser extent than in previous aspirates [Figure 4; sixth specimen, Table 1]. Immunocytochemistry for S100 was positive in these histiocytes. CD68 and ACT were negative in the large histiocytes but numerous small mononuclear histiocytic cells in the background were positive for both these markers [Figure 3 Inset]. These had much smaller nuclei and scant cytoplasm as compared to RDD histiocytes.

Figure 4.

Aspirate from left cervical lymph node in mild exacerbation, showing numerous histiocytes with large nuclei. Emperipolesis is infrequent, but definite. Inset: Immunocytochemistry for CD68 is negative in the large RDD histiocytes with emperipolesis (arrow) but positive in scattered mononuclear cells in the background (Papanicolaou, ×400, Inset: CD68 immunocytochemistry, ×100)

A left cervical lymph node biopsy was obtained during involution phase [seventh specimen, Table 1]. The lymph node measured one cm in size. Slides showed extensive lymph nodal necrosis and apoptosis with perinodal fibrosis. In a few foci occasional foamy histiocytes were identified, however, there was no emperipolesis. Vessels showed vasculitis and fibrinoid necrosis. No definite opinion was possible.

A right cervical lymph node was biopsied in stable phase [eighth specimen, Table 1]. The lymph node measured 2.5 cm in size and showed maintained architecture with perinodal fibrosis. Most of the lymph node substance was occupied by dilated sinuses filled with foamy histiocytes which showed emperipolesis of lymphocytes and plasma cells [Figure 5]. Numerous plasma cells were seen in and around the sinuses. Hilum showed marked fibrosis. Immunocytochemistry for S100 was positive. A final histopathological diagnosis of RDD was established.

Figure 5.

Biopsy from left cervical lymph node in stable phase showing dilated sinuses containing foamy histiocytes with emperipolesis. Numerous plasma cells are seen in the perisinusoidal lymphoid tissue (H and E, ×200)

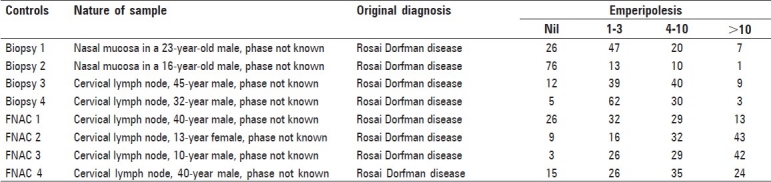

Control cases showed variable extent of emperipolesis which has been quantified as detailed in Table 2. It was more in cytology specimens as compared to histopathology specimens and varied from case to case and sample to sample.

Table 2.

Quantification of emperipolesis on control samples

Discussion

RDD to this date remains an idiopathic entity, the etiology of which remains unknown despite intense investigations over the last 20 years.[7–14] In the absence of understanding regarding pathogenesis, numerous reports in the literature have concentrated on unusual sites of involvement by RDD. Emperipolesis is considered a hallmark for the histopathological diagnosis of RDD.[3] This feature is always identified and is requisite for making a histopathological diagnosis of RDD.[8] Immunohistochemical investigations into the nature of histiocytes in RDD have, however, thrown up many markers which have diagnostic utility. Histiocytes of RDD are S100-positive, setting them apart from the more usual sinus histiocytes and phagocytic cells in general.[15,16] Unlike Langerhans cells which are also S100-positive, histiocytes of RDD are CD1a-negative.[9,15,16] CD68, a marker for phagocytic histiocytes is also positive in histiocytes of RDD[15] as is ACT.[4]

Thus the histiocytes of RDD have some features of antigen-presenting cells or Langerhans cells (S100-positive) and some features of phagocytic histiocytes (positivity for CD68, ACT, pan-macrophage markers like EBM11, HAM 56, and Leu-M3; antigens functionally associated with phagocytosis like Fc receptor for IgG and complement receptor 3; lysosomal enzymes like lysozyme, ACT and alpha 1-antitrypsin).[4,13,15] Morphologically and electron microscopically, however, RDD histiocytes have none of the features of mature Langerhans cells, the immature cells of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, or phagocytic cells.[3,17] Antigens associated with early inflammation (Mac-387, 27E10), antigens found on circulating monocytes but not tissue macrophages (OKM5, Leu-M1) and activation antigens (Ki-1, transferrin receptor and interleukin 2) are also expressed by these histiocytes.[13] These features suggest that RDD histiocytes are functionally activated macrophages recently derived from circulating monocytes. It has also been shown that the sinuses of RDD nodes, in addition to the classic histiocytes with emperipolesis, also contain large numbers of small-sized mononuclear cells negative for S100 but positive for CD11b, CD11c, CD14, CD16, CD33, CD36, lysozyme, Mac 387 and HLA-DR.[12] In the same study, the RDD histiocytes with emperipolesis were positive for S100, CD11c, CD14, CD33, CD68, and LN 5.[12] These findings suggested that monocytes derived from the marrow migrate into the sinuses of RDD nodes where they are transformed into the RDD histiocytes, possibly by local cytokine modulation. The common expression of S100, fascin, cathepsin D and cathepsin E by RDD histiocytes points towards antigen-presenting cell differentiation.[8,11] Cytokine expression pattern by RDD histiocytes is however unique. Expression pattern of mRNA suggests that RDD histiocytes express tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, interleukin (IL) 1 and IL 6. In contrast, mature Langerhans cells in dermatopathic lymphadenitis did not express any of these cytokines. Immature Langerhans cells of Langerhans cell histiocytosis mostly expressed TNF alpha, although occasional cases expressed IL-1. IL-6 expression was seen in reactive mononuclear cells.[10]

The current working hypothesis on pathogenesis of RDD is therefore recruitment of marrow monocytes from peripheral blood into lymph nodal sinuses or extranodal sites and their transformation into the immunophenotypically distinct RDD histiocytes which demonstrate emperipolesis and functional uniqueness in terms of cytokine expression profile.[10] Release of cytokines like TNF alpha from these cells is responsible for the genesis of fever and other systemic symptoms. However, the morphological counterpart of such an evolutionary transformation or variation in morphology with timing of biopsy are not well documented.

In the present case, RDD has been biopsied at various times in the course of the disease, with emperipolesis not always being identified. These findings fit well with the current working hypothesis detailed above. Rapidly enlarging nodes and extra-nodal tissue affected with RDD showed less degree of emperipolesis, with predominance of S100-positive foamy histiocytes. In aspirates and biopsies in stable phase, emperipolesis was easy to find. These features suggest that early transformation of monocytes into RDD histiocytes occurs in exacerbation and that emperipolesis takes more time to be well developed. Small mononuclear cells positive for CD68 and ACT but negative for S100 seen in the background may indicate progressive disease activity. Since two different types of histiocytic cells are present together in RDD, accurate interpretation of immunocytochemical findings is essential.

The variability in extent of emperipolesis observed in this patient indicates that it is a dynamic event which takes time to develop. Variable extent of emperipolesis was also seen in eight aspirates and biopsies from other patients [Table 2], although these were from patients with unequivocal diagnosis of RDD on initial sampling. Emperipolesis was picked up without difficulty in all these cases. Status of disease activity was not known in these patients.

Sampling of rapidly involuting node yielded mostly necrotic and apoptotic cells. Although it is not possible to identify the exact nature of the apoptotic cells, it is reasonable to assume these were the mononuclear and histiocytic cell components which may be involuting in response to changes in the cytokine milieu. Sampling of stable disease therefore yields diagnostically useful tissue whereas sampling during exacerbation and involution phases yields tissue inadequate for definitive diagnosis.

Differential diagnostic considerations from the present case are important. If emperipolesis is focal in certain stages of RDD, these cases will be missed on biopsy. There are previous reports of RDD being misdiagnosed as toxoplasma lymphadenitis.[15] Overlap of morphological features of rhinoscleroma and RDD have also been reported.[18] Rhinoscleroma was an important differential diagnostic consideration in the present case in view of the foamy histiocytes without emperipolesis presenting in the nose. Xanthoma-like appearance of cutaneous RDD histiocytes is also known.[9] Therefore, presence of foamy histiocytes in the correct clinical context should prompt a dif ferential diagnosis of RDD even in the absence or focality of emperipolesis. Similarly, extensively necrotic and apoptotic nodes can be from an involuting stage of RDD.

Emperipolesis is more easily identified and quantified in aspirates than biopsy. The RDD histiocytes are very large, from 50 to 100 microns or more in size. A five-micron section would sample only a tenth or less of the RDD histiocyte cytoplasm. If emperipolesis is restricted to just one or two lymphocytes in only a few of the RDD histiocytes, as seen in many cells of the second aspirate, biopsy diagnosis of RDD would be difficult. In cytology smears on the other hand, the entire RDD histiocyte is sampled and with the transparent Papanicolaou stain, can be analysed in its entirety. Because of these reasons quantification of emperipolesis in biopsies may not correlate with that seen in aspirates, although it has been performed in this study for comparison.

A number of events in RDD are completely idiopathic. The factors initiating this peculiar inflammatory response of recruitment of monocytes and their transformation in situ remain unknown. The etiology of emperipolesis and its nature are also unknown. Without understanding the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying these two key factors in RDD, the disease remains a morphologic entity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: A newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: A pseudolymphomatous benign disorder: Analysis of 34 cases. Cancer. 1972;30:1174–88. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197211)30:5<1174::aid-cncr2820300507>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosai J. Lymph node. Mosby: St. Louis; 2004. Rosai and Ackerman's surgical pathology. Chapter 21; pp. 1911–3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettinato G, Manivel JC, d’Amore ES, Petrella G. Fine needle aspiration cytology and immunocytochemical characterization of the histiocytes in sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman syndrome) Acta Cytol. 1990;34:771–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshpande V, Verma K. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology of Rosai Dorfman disease. Cytopathology. 1998;9:329–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2303.1998.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh NG, Kapila K, Mathur S, Ray R, Verma K. Rosai-Dorfman disease manifesting as multiple subcutaneous nodules: Report of a case with diagnosis on a fine needle aspirate. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:215–8. doi: 10.1159/000326319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Middel P, Hemmerlein B, Fayyazi A, Kaboth U, Radzun HJ. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: Evidence for its relationship to macrophages and for a cytokine-related disorder. Histopathology. 1999;35:525–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffe R, DeVaughn D, Langhoff E. Fascin and the differential diagnosis of childhood histiocytic lesions. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1998;1:216–21. doi: 10.1007/s100249900029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quaglino P, Tomasini C, Novelli M, Colonna S, Bernengo MG. Immunohistologic findings and adhesion molecule pattern in primary pure cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease with xanthomatous features. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:393–8. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199808000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foss HD, Herbst H, Araujo I, Hummel M, Berg E, Schmitt-Graff A, et al. Monokine expression in Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis and sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease) J Pathol. 1996;179:60–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199605)179:1<60::AID-PATH533>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulli M, Feller AC, Boveri E, Kindl S, Berti E, Rosso R, et al. Cathepsin D and E co-expression in sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease) and Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis: Further evidences of a phenotypic overlap between these histiocytic disorders. Virchows Arch. 1994;424:601–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00195773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulli M, Rosso R, Kindl S, Boveri E, Marocolo D, Chioda C, et al. Immunophenotypic characterization of the cell infiltrate in five cases of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease) Hum Pathol. 1992;23:647–54. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisen RN, Buckley PJ, Rosai J. Immunophenotypic characterization of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease) Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonetti F, Chilosi M, Menestrina F, Scarpa A, Pelicci PG, Amorosi E, et al. Immunohistological analysis of Rosai-Dorfman histiocytosis: A disease of S-100 + CD1-histiocytes. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1987;411:129–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00712736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kara IO, Ergin M, Sahin B, Inal S, Tasova Y. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman's disease) previously misdiagnosed as toxoplasma lymphadenitis. Leuk Lymph. 2004;45:1037–41. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000149340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carbone A, Passannante A, Gloghini A, Devaney KO, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Review of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease) of head and neck. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:1095–104. doi: 10.1177/000348949910801113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyer VK, Kapila K, Verma K. Fine needle aspiration cytology of dermatopathic lymphadenitis. Acta Cytol. 1998;42:1347–51. doi: 10.1159/000332166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasper HU, Hegenbarth V, Buhtz P. Rhinoscleroma associated with Rosai-Dorfman reaction of regional lymph nodes. Pathol Int. 2004;54:101–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]