Abstract

Background:

Computed tomography (CT)-guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is regarded as a rapid, safe, and accurate diagnostic tool in examining thoracic mass lesions for the last three decades.

Aims:

To assess the role of CT-guided FNAC in thoracic mass lesions, to analyse the results, and to compare the results with other studies.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty-seven patients were studied over a year (July 2007 to June 2008) for their age, sex, and topographic distribution, pleural infiltration (based on CT findings), and cytological diagnoses.

Results:

Out of 57 cases, 78.9% (n = 45) were male and 21.1% (n = 12) were female. The age range varied from 34 to 79 years with the peak in the fifth decade. There were 54 parenchymal (lung) tumors and the remaining three tumor cases were mediastinal. The most common tumor was squamous cell carcinoma (42.6%) followed by adenocarcinoma (29.6%) and small cell carcinoma. Postprocedural complications were minimal and were noted in only three cases (a little pulmonary hemorrhage in two and hemoptysis in one).

Conclusions:

CT-guided FNAC of thoracic mass lesions provides a rapid and safe diagnostic procedure with minimal complications. The categorical diagnosis can also be achieved on the basis of cytomorphology. The figures obtained from this study are comparable with other studies except for a few differences.

Keywords: CT guided FNAC, lung, thoracic mass lesions

Introduction

Percutaneous, transthoracic fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is a well established diagnostic method used in the cytological evaluation of thoracic mass lesions for the last three decades. Nowadays, computed tomography (CT)-guided FNAC of lesions of the lungs and the mediastinum is widely practised in several institutions where the facilities of standard imaging techniques and cytopathology are available. This procedure provides a safe, rapid, and accurate diagnosis in patients having thoracic mass lesions.[1–3] Moreover, CT-guided FNAC plays an extremely vital role in small thoracic mass lesions and deep mediastinal nodes in which needle placement is correctly possible by avoiding any surrounding blood vessels and adjacent cardiac structures.[4,5] In a well conducted series, Wallace et al.[6] concluded that CT-guided FNAC of small thoracic mass lesions (one cm or smaller) can provide high diagnostic accuracy rates approaching those of larger lesions. In cases of malignancy of the lungs, cytopathological examination of material obtained by CT-guided FNAC offers a quick and specific diagnosis which helps clinicians implement appropriate anticancer measures like chemotherapy and radiotherapy. It has also been demonstrated in literature that CT-guided FNAC is an accurate and sensitive way of diagnosing malignancy of the lungs.[7–9] On the other hand, postprocedure complications are fewer except for pneumothorax, pulmonary hemorrhage, and hemoptysis in a small percentage of cases. Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bleeding diathesis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension are the relative contraindications.[4]

The purpose of the current study was to analyse the age, sex, and topographic distribution, the size and cytopathological diagnosis of thoracic mass lesions using CT-guided FNAC.

Materials and Methods

This study included 57 patients who had thoracic mass lesions that were suspected to be neoplastic disease in most of the cases by chest radiograph and CT scan. Consecutive CT-guided FNAC of lung and mediastinal mass lesions of these patients was performed in our institution from July 2007 to June 2008 with immediate cytological assessment.

Proper aseptic care was taken by cleaning the skin surface with povidone iodine before every FNAC. Aspiration was done using 21G, 88 mm long spinal needle through percutaneous and transthoracic approaches, identifying the lesion in the exact section by CT scan after the measurement of the site of entry of the needle, route of the needle, and the distance between the skin and lesion on the CT scan monitor. The patient's position was supine, prone, or lateral decubitus depending on the location of the thoracic mass lesions. Following placement of the needle, a CT scan slice was taken to ascertain whether the tip of the needle was within the mass. The aspirate was obtained by to and fro and rotating movements of the needle within the lesions and five to ten smears were prepared immediately from the sample in the CT scan room. Air-dried smears were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain whereas alcohol-fixed smears were stained with Papanicolaou and hematoxylin and eosin stains for rapid cytopathological evaluation of the lesions.

A follow-up CT scan was done in every patient immediately after the procedure to rule out pneumothorax. Although all patients with postprocedural complications were observed carefully, no active treatment was required for any of these patients.

Results

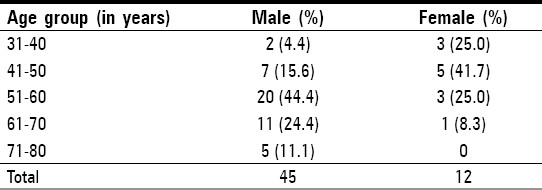

Out of 57 cases involved in our present study, 45 (78.9%) were male and 12 (21.1%) were female. The youngest patient was a female of 34 years whereas the oldest was a male of 79 years; the overall mean age of all the patients was 56.8 years. A genderwise examination of the patients′ ages revealed that the mean age was 59.2 years for the males and 47.1 years for the females. Two significant findings of our study were that 20 out of 45 male patients were in the age group of 51-60 years whereas there were no female patients in the age group of 71-80 years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution of patients

There were 54 (94.7%) parenchymal (lung) tumors: 31 were found in the right lung and 23 in the left lung field; only three cases (5.3%) were located in the anterior mediastinum. Among 54 cases of parenchymal (lung) tumors, 21 cases (36.8%) were located in the upper zone, followed by 16 cases (28.1%) in the parahilar region, eight cases (14.0%) in the lower zone, and six cases (10.6%) in the mid-zone. Two very big tumors (3.5%) involved both the upper and mid zones and one very big tumor (1.7%) involved both the mid and lower zones.

According to the CT findings, the size of the lesions varied from 1.2 to 13.6 cm in diameter. Only 16 cases (14 lung mass and two mediastinal mass) were ≤ five cm in diameter. The size of 38 lesions (37 lung mass and one mediastinal mass) varied from 5.1 to 10 cm whereas the remaining three cases were very big (> 10 cm in diameter).

Among the lung masses, the pleura were infiltrated in seven cases and in nine cases, the mass was very close to pleura, i.e ., the distance was ≤ one cm.

Out of 57 cases of thoracic mass lesions, definitive cytological diagnosis was obtained in 54 cases and the rest three cases were inconclusive and descriptive report was given to the patients. Among 54 cytologically diagnosed cases, 52 were malignant (including both lung and mediastinal tumors) and the remaining two cases were diagnosed as granulomatous inflammation that was consistent with tuberculosis [Table 2]. All the 23 squamous cell carcinomas diagnosed in our series were located centrally although in the case of the larger tumors, peripheral parts of the lung were also involved. In the case of the 16 adenocarcinomas, nine were peripheral and seven were central in location. Microscopically, both the squamous cell carcinomas and the adenocarcinomas showed classical cytomorphological features.

Table 2.

Distribution of various thoracic mass lesions

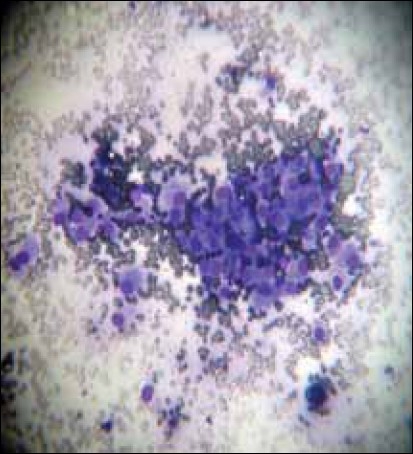

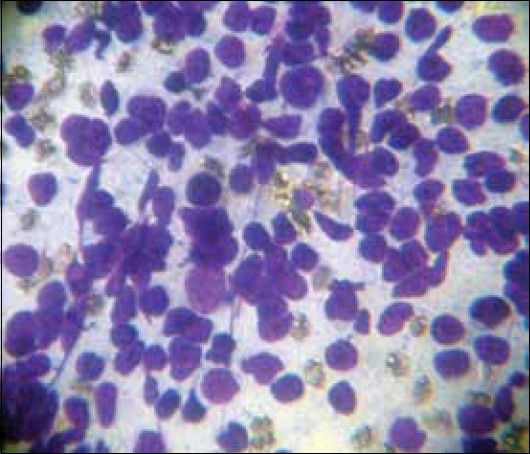

Only one metastatic lung tumor was diagnosed in a known case of clear cell type of renal cell carcinoma, where we obtained cellular smears having cohesive clusters of cells with abundant vacuolated cytoplasm and mildly pleomorphic, round nuclei [Figure 1]. The single mediastinal Hodgkin's disease showed the presence of typical Reed-Sternberg cells. In two cases of mediastinal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, the cytological smears were highly cellular, consisting of discrete, monotonous populations of cells, having enlarged nuclei with immature chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of FNAC smears (obtained by CT guided FNAC) showing the malignant cells in metastatic lung tumor from renal cell carcinoma (MGG, ×400)

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of FNAC smears (obtained by CT guided FNAC from anterior mediastinal mass) showing the cells of non-Hodgkin's lypmhoma (MGG, ×400)

Postprocedural complications were seen in three cases: post FNAC CT scans showed small amounts of pulmonary hemorrhage in two cases and one of the patients suffered from hemoptysis on one occasion just after the aspiration.

Discussion

In the present study, all the 57 patients were adults with even the three cases of mediastinal tumors being found in adults patients. The peak age incidence (51–60 years) was the same as that documented in one recent study.[10] The mean age (56.8 years) was also almost similar (56.4 years) to a study conducted by Singh et al.[4] However, Wallace et al.[6] showed a slightly higher mean age of 61.3 years in the case of CT-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of small (≤ one cm) pulmonary lesions. The age range varied in most of the series from the third to the eighth decade, whereas in a study of 190 cases of thoracic mass lesions, the age range varied from six to 83 years which included three pediatric patients.[11]

Male patients (78.9%) showed significant preponderance in our study compared to females (21.1%). In two recent national studies, the percentage of male patients was a little higher than in our series, i.e ., 88.0[10] and 80.6%.[11] However, the study by Sing et al,[4] showed a significantly lower incidence of male patients (52.0%). In two international studies, the percentage of male patients was found to be 55.7[6] and 71.1%.[12]

In this study, lung tumors were located more in the right side than in the left. The anterior mediastinum is the only site where all three mediastinal tumors were found. We tried to make a zone-wise distribution of lung tumors on the basis of CT scan findings and found that the upper zone is the most common site followed by the parahilar region.

The lesions were quite large in our series: the majority of the thoracic mass lesions (37 out of 57 cases) were 5–10 cm in diameter. The thoracic mass lesions were more variably sized (1.2-13.6 cm) than those reported in another series (1.2-5.6 cm).[4]

Consistent with findings from study by Sing et al,[4] we observed a notable correlation of complications with the distance of the pleura from the lesion. All complications like pulmonary hemorrhage (in two cases) and hemoptysis (in one case) were seen where the lesions were the furthest, i.e ., 5–6 cm away from the pleura. This was likely to be due to larger amounts of normal lung tissue that had to be traversed by the needle. However, pneumothorax, the most common complication of other studies, was not found in any case in our study. The overall rate of complications (5.2%) in our study was also remarkably less than other series where the range varied from six to 50%.[1,4–7,11,12] This was thought to be due to the larger size of the tumor masses in our series and also due to our meticulous and proper aspiration procedure.

Cytological diagnosis was made in 54 out of 57 cases (94.7%) and the high incidence of malignancy (96.5%) was comparable with that found in other studies.[1,4,5,11,13] Among all 48 cases of primary lung tumors, the most common (n = 23; 42.6%) was squamous cell carcinoma followed by 29.6% of adenocarcinoma and 9.3% of small cell carcinoma. This order of frequency was also found in two recently published national studies.[10,11] In our study, both large cell carcinomas and poorly differentiated carcinomas were equally prevalent (3.7% each). However, in two studies: one national and one international,[10,14] the prevalence of large cell carcinoma was more than the present series. The incidence of adenocarcinoma was reported to be significantly higher than that of squamous cell carcinoma in a study by Tan et al.[12]

Only one metastatic lung tumor was found where the primary was in the kidney. All three mediastinal tumors (5.6%) were malignant which included two cases of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and one case of Hodgkin's disease.

Both the benign non-neoplastic lesions were diagnosed as granulomatous inflammation consistent with tuberculosis. The incidence of inconclusive (unsatisfactory for diagnosis) cases (5.6%) in our series was less than that in other studies.[4,11] The inconclusive results were due to scanty aspirate as well as scanty cellularity. These three cases were later diagnosed histopathologically and treated in other institutions as squamous cell carcinomas.

This study was, thus, based on cytopathological evaluation. The diagnosis and treatment of various thoracic mass leisions were delayed due to the poor socio-economic status of this region. During aspiration, most of the tumors were found to be large. The majority of cases of the primary lung tumors (n = 33) and the single case of metastasis died within three to six months of diagnosis after getting a few courses of chemotherapy. The remaining 15 cases of primary lung tumor and all the three cases of mediastinal tumor were lost during follow-up. The two cases of pulmonary tuberculosis were cured by antitubercular therapy.

Conclusions

CT-guided FNAC of thoracic mass lesions is a safe, rapid, and reliable procedure with minimal complications. It provides very early diagnosis and exact subclassification of various lung tumors on the basis of cytomorphology. Benign nonneoplastic lesions like tuberculosis can also be diagnosed with certainty by this technique. The results of this study are mostly comparable with those of other national and international series. The early and accurate diagnosis obtained by CT-guided FNAC helps to formulate immediate, effective management of thoracic mass lesions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Stewart CJ, Stewart IS. Immediate assessment of fine needle aspiration cytology of lung. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:839–43. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.10.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salazar AM, Westcott JL. The role of transthoracic needle biopsy for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Clin Chest Med. 1993;14:99–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders C. Transthoracic needle aspiration. Clin Chest Med. 1992;13:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sing JP, Garg L, Setia V. Compared tomography (CT) guided transthoracic needle aspiration cytology in difficult thoracic mass lesions – not approachable by USG. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2004;14:395–400. [Google Scholar]

- 5.vanSonnenberg E, Casola G, Ho M, Neff CC, Varney RR, Wittich GR, et al. Difficult thoracic lesions: CT-guided biopsy experience in 150 cases. Radiology. 1988;167:457–61. doi: 10.1148/radiology.167.2.3357956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace MJ, Krishnamurthy S, Broemeling LD, Gupta S, Ahrar K, Morello FA, Jr, et al. CT-guided percutaneous fine-needle aspiration biopsy of small (≤1-cm) pulmonary lesions. Radiology. 2002;225:823–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2253011465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullan CP, Kelly BE, Ellis PK, Hughes S, Anderson N, McCluggage WG. CT-guided fine-needle aspiration of lung nodules: Effect on outcome of using coaxial technique and immediate cytological evaluation. Ulster Med J. 2004;73:32–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox JE, Chiles C, McManus CM, Aquino SL, Choplin RH. Transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy: Variables that affect risk of pneumothorax. Radiology. 1999;212:165–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.1.r99jl33165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko JP, Shepard JO, Drucker EA, Aquino SL, Sharma A, Sabloff B, et al. Factors influencing pneumothorax rate at lung biopsy: Are dwell time and angle of pleural puncture contributing factors? Radiology. 2001;218:491–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.2.r01fe33491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah S, Shukla K, Patel P. Role of fine needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis of lung tumors – A study of 100 cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2007;50:56–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandyopadhyay A, Laha R, Das TK, Sen S, Mangal S, Mitra PK. CT guided fine needle aspiration cytology of thoracic mass lesions: A prospective study of immediate cytological evaluation. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2007;50:51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan KB, Thamboo TP, Wang SC, Nilsson B, Rajwanshi A, Salto-Tellez M. Audit of transthoracic fine needle aspiration of the lung: Cytological subclassification of bronchogenic carcinomas and diagnosis of tuberculosis. Singapore Med J. 2002;43:570–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abrari A, Aziz M, Haq R. Cytology of lung tumors – study of 60 cases with emphasis on accuracy and problem areas. J Cytol. 2003;20:79–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gouliamos AD, Giannopoulos DH, Panagi GM, Fletoridis NK, Deligeorgi-Politi HA, Vlahos LJ. Computed tomography-guided fine needle aspiration of peripheral lung opacities: An initial diagnostic procedure? Acta Cytol. 2000;44:344–8. doi: 10.1159/000328476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]