Abstract

Objectives:

To assess the utility of the cell block preparation method in increasing the sensitivity of cytodiagnosis of serous fluids and to know the primary site of malignant effusions.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 190 cases were subjected to routine smear examination as well as cell block preparation. After the cytological diagnosis, each case was objectively analysed for cellularity, arrangement (acini, papillae, cell balls, and proliferation spheres), cytoplasmic, and nuclear details.

Results:

Out of 190 cases, 70 cases were found to be malignant and had been examined in smears and paraffin-embedded cell blocks. Using a combination of the cell block and smear techniques yielded 13% more malignant cases than what were detected using smears by themselves. The combined technique helped to ascertain the primary site of malignancy in 83.3% of the cases, whereas the primary site could not be ascertained in 17.7% of the cases.

Conclusions:

The cell block technique not only increased the positive results, but also helped to demonstrate better architectural patterns, which could be of great help in making correct diagnosis of the primary site. The cell block technique was also useful for special stains and immunohistochemistry and can give morphological details by preserving the architectural patterns.

Keywords: Cell block, malignant effusions, smear

Introduction

Accurately diagnosing cells as being either malignant or benign ‘reactive mesothelial cells’ in serous effusions is a common diagnostic problem. The lower sensitivity of cytodiagnosis of effusions is mainly attributable to bland morphological details of cells, overcrowding or overlapping of cells, cell loss, and changes due to different laboratory processing methods.

It has been seen in various studies that the cytological examination of fluids by means of smears, however carefully prepared, leaves behind a large residue that is not further investigated but that might contain valuable diagnostic material. This residual material can be evaluated in a simple and expedient fashion by treating it as a cell block, embedded in paraffin, and examined in addition to the routine smears.[1,2]

Cell blocks are particularly useful when the cytological abnormalities are misleading, such as in reactive mesothelial cells, or obscure as in occasional well differentiated adenocarcinoma.[3] The present study has been undertaken to assess the utility of the cell block preparation method in increasing the sensitivity of cytodiagnosis of serous fluids and to know the primary site of malignant effusions.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted on 190 cases of serous effusion (pleural 88, peritoneal 92, and pericardial 10) after thorough clinical and radiological examination. Fluids thus obtained were first examined by naked eye for physical characteristics and then divided into two halves.

Half of the specimen was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 15 minutes and the smear prepared was then stained with Giemsa or hematoxylin and eosin (H and E). For the cell block preparation, the other half of the fluid specimen was fixed in a 1:1 solution of 10% alcohol: formalin for one hour. After fixation, the specimen was centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10–15 minutes. The supernatant was poured off and the sediment completely drained off by inverting the tube over Whatman filter paper. The sediment was then wrapped in the same filter paper and processed in histokinette as part of routine paraffin section histopathology. Special staining, including periodic acid Schiff (PAS), was done whenever needed.

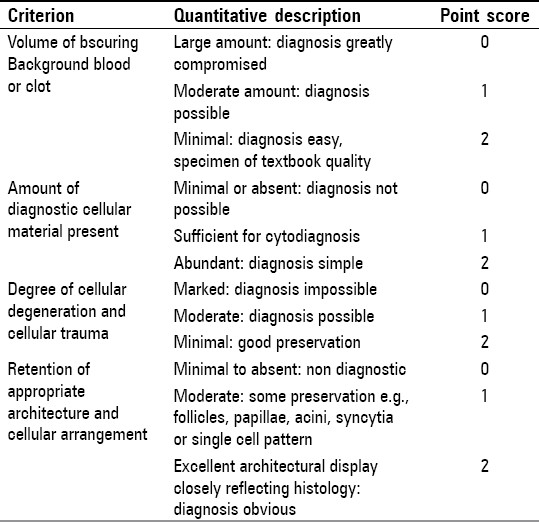

A cytological diagnosis was rendered for each case seen and each individual slide was objectively analysed for cellularity, arrangement (acini, papillae, cell balls, and proliferation spheres), cytoplasmic, and nuclear details using the point scoring system described by Mairet al.[4][Table 1].

Table 1.

Criteria for the assessment of the quality of smear and cell block[4]

According to the criteria mentioned above, comments were rendered on the quality of the slides by qualitatively grouping them into three categories:

-

1)

Diagnostically unsuitable

-

2)

Diagnostically adequate

-

3)

Diagnostically superior

Results

Out of 190 cases studied, 120 (63.15%) cases were of different reactive effusions and 70 (36.85%) cases were of malignant effusions. Among the reactive effusions, 58 (48.33%) cases were of pleural fluid, 54 (45.0%) cases were of peritoneal fluid, and eight (6.66%) cases were of pericardial fluid.

The majority (22, 18.33%) of cases were due to tuberculosis. Other diseases causing different effusions were: 18 (15%) congestive heart failure cases, 18 (15%) cirrhosis of liver cases, 14 (11.66%) bacterial infection cases, eight (6.66%) viral infection cases, ten (8.33%) pneumonia cases, ten (8.33%) renal failure cases, six (5%) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cases and eight (6.66%) cases of undetermined aetiology.

Out of 120 cases of reactive effusion, the majority (40, 33.3%) of the cases revealed scanty cellularity, inflammation with polymorphs in 26 (21.7%) cases, moderate cellularity showing a mixed picture in 24 (20.0%) cases, predominantly mesothelial cells in six (5.0%) cases, and predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate in 16 (13.3%) cases.

Out of 70 cases studied, diagnosis was made by histopathology in 58 cases (82.8%) and by fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in 12 cases (17.2%), which comprised of 16 cases of lung carcinoma, 14 cases of malignant ovarian neoplasm, ten cases of breast carcinoma, 16 cases of gastrointestinal tract (GIT) malignancy, eight cases of liver and gall bladder (GB) malignancy, four cases of lymphoma, and two cases of mesothelioma. Peritoneal fluid was obtained in 38 cases (54.25%), pleural fluid in 30 cases (42.85%), and pericardial fluid in two cases (2.87%) for smear examination and cell block preparation.

Cytological examination of the smear prepared from the first sample was found to be positive for malignant cells in 38 cases (54.28%). In mesothelioma, malignant cells were noticed in both the cases studied (100%). Diagnostic accuracy ranged from 40 (carcinoma breast) to 64.29% (malignant ovarian neoplasm) [Table 2]. Six cases (8.55%) were suspicious and 26 (37.2%) were labeled as being negative [Figure 1].

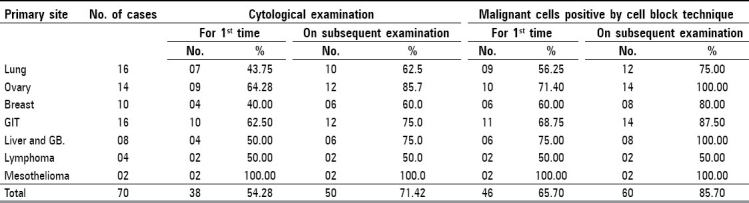

Table 2.

Percentage increase in yield by cell block technique taking into consideration the numbers of specimen taken for histologically proved primary tumors

Figure 1.

Ascitic cell block preparation of ovarian papillary carcinoma showing papillary arrangement of malignant cells (H and E, ×200)

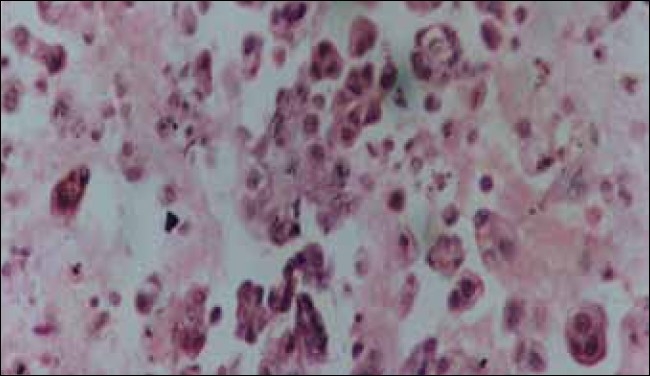

Cell block revealed better diagnostic accuracy than cytological smears. Out of 70 cases, 46 cases (65.7%) were detected to be positive for malignant cells. Diagnostic accuracy ranged from 50 (in lymphoma) to 71.4% (in malignant ovarian neoplasm) [Table 2]. Eight cases (11.4%) were suspicious whereas 16 cases (22.8%) were labeled as being negative [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Ascitic fluid smear from a case of ovarian serous carcinoma (H and E, ×500)

The diagnostic yield was increased by both the techniques with the examination of more specimens. Cytological smear examination increased diagnostic yield for malignant cells by 17.14% (from 54.28 to 71.42%) whereas cell block technique increased the same diagnostic yield by 20% (from 65.7 to 85.7%).

When the cytological smears and cell block techniques were studied for their quality by using the point scoring system of Mairet al.,[4] it was noticed that 26% of the smears and 12% of cell blocks scored 0 and were unsuitable for diagnosis. Some (20%) of the smears and 21% of cell blocks scored one and their quality was diagnostically adequate. More than half (54%) of the smears and 67% of cell blocks were considered to be diagnostically superior, giving textbook quality results.

With the help of cell blocks and smears, it was possible to ascertain the primary site of malignancy in 83.3% cases, but not in 16.7% cases due to the lack of clear cellular morphology.

Discussion

In the present study, out of the total 120 cases of reactive effusions, the majority (58, 48.3%) of the cases were of pleural effusion, followed by 54 (45%) peritoneal fluid cases whereas the least number (eight, 6.7%) of cases were from pericardial effusion. The nonmalignant effusion cases were comprised of 22 tuberculosis (18.3%), 18 congestive heart failure (15.0%), and 18 cirrhosis of liver (15.0%) cases.

In their study of effusion, Luse and Reagan[5] reported that the maximum number of cases of non-malignant effusion were of pleural effusion, followed by peritoneal fluid, whereas the least number of cases were of pericardial effusion. According to them, the majority of the cases were due to underlying congestive heart failure comprising 18% of all cases, followed by cirrhosis and tuberculosis comprising 11 and 8% of the cases respectively. In the present study, the majority of reactive effusion cases was due to underlying tuberculosis. This might be due to the high prevalence of tubercular infection in the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh where the study has been conducted.[6,7]

In the present study on 120 cases of reactive effusion, 40 (33.3%) cases had scanty cellularity, 26 (21.7%) cases had inflammatory infiltrate, eight (6.7%) cases showed blood, 24 (20.0%) cases mixed cellularity with moderate cell count, 16 (13.3%) cases predominated by lymphocytes, and six (05.0%) cases had mesothelial cells.

Similar findings were recorded by Melamed[8] who described the different cell patterns in effusions without identifiable cancers and found that one-third of the cases showed scanty cellularity and around one-third comprised of inflammatory or hemorrhagic effusions.

In the present study, out of the total 70 cases of histologically/FNAC-confirmed malignant tumors, 50 (71.42%) cases were reported to be positive for malignant cells by smear examination. This is in accordance with Chandler[9] who got 65–76.0% accuracy in results by smear examination of the various body cavity effusions.

In the present study, out of the total 70 cases of histologically / FNAC-confirmed malignant tumors, 60 (85.7%) cases were found to be positive by the cell block method. The present study thus has an accuracy of 85.72% which is in accordance with Zemansky,[10] who observed a diagnostic accuracy of around 90.0%.

In present study, out of the total 14 cases of primary ovarian tumors, 12 (85.7%) cases were found to be positive by smear examination but all (100%) were found to be positive by the cell block technique.

The study is consistent with Mouroe[11] who worked on carcinoma cells in thoracic and abdominal fluids, and found that the highest incidence of carcinoma cells (100.0%) was detected in cases of ovarian carcinoma.

In the present study, on comparing the accuracy of smear examination and the cell block technique, cell block technique and smear examination gave different results for malignancy positivity (85.7vs71.42.0% respectively).

Ceelen[12] got 89% positive diagnoses with the cell block technique and 71% with smear examination. Taftet al,[13] also compared the cell block technique and smear examination and concluded that the cell block technique yielded better results than the smear. Thus, the present findings are in close approximation to those of studies by the above investigators.

In the present study, the cell block technique gave better diagnostic quality at a higher rate, giving results of textbook quality.

Similar observations were noticed by others,[14,15] who reported that organoid arrangements and the pathognomic of malignancy are better seen in cell blocks than in smears.

The average percentage of specimens with positive malignant tumor cells was 63.0% in the present study. This is in close approximation to the work done by Sarahet al,[16] on the histocytological study of effusions associated with malignant tumors. According to their study, tumor cells were identified in 67.5% of the fluid specimens examined.

In the present study, positivity for malignancy was 66.0% on initial diagnosis by the cell block method, which increased to 86% on subsequent examination of the drained specimens at frequent intervals. Thus, the percentage of positive results increased by 20.0% on reviewing the specimens. This is consistent with Fumikazuet al. ,[17] who also obtained some suspicious or negative results on examining the first specimens of the fluids but whose positive diagnosis rates increased by 21% on repeated examination of the fluids at frequent intervals.

In the present study, simultaneous use of the cell block technique and smear examination increased diagnostic accuracy by 13.0%, consistent with the 12% increase reported by. Richardsonet al.[18]

The cell block technique not only increased the positive results, but also helped to demonstrate better architectural patterns which could be of great help in approaching the correct diagnosis of the primary site. It was possible to ascertain the primary site of malignancy in 83.3% of the cases with the help of cell blocks and smears, the remaining being unclear due to lack of clear cellular morphology. These results are consistent with Khanet al.[3] who determined the primary site of malignancy with certainty in 81.3% of the cases.

The cell block technique has an added advantage that multiple sections of the same material can be obtained for special stains and immunohistochemistry.[3] Apart from this advantage, morphological details can also be obtained with the cell block method, which include preservation of the architectural pattern like cell balls and papillae and three dimensional clusters, excellent nuclear and cytoplasmic details, and individual cell characteristics. On the other hand, fragments of tissue can easily be interpreted in a biopsy-like fashion.

It is thus concluded from the present study that it is advisable to study paraffin sections by using the cell block method before discarding specimens that are negative for malignant cells by smear examination.

Similar conclusions were drawn by Foord and Wetmore[19] who conducted cellular studies of effusions by using smears and paraffin sections. They preferred to study paraffin sections before giving the final diagnosis because it was more accurate and as it was easier to demonstrate cellular relationships with the cell block technique.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Dekker A, Bupp PA. Cytology of serous effusion: An investigation into the usefulness of cell blocks versus smears. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;70:855–60. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/70.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunze H. The comparative diagnostic accuracy, efficiency and specificity of cytological techniques used in the diagnosis of malignant neoplasms in serous effusions of pleural and pericardial cavities. Acta Cytol. 1964;8:150–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan N, Sherwani KR, Afroz N, Kapoor S. Usefulness of Cell Blocks Versus smears in Malignant effusion cases. J Cytol. 2006;23:129–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mair, Dunbar F, Becker PJ, Du Plessis W. Fine Needle cytology: Is aspiration suction necessary. A study of 100 masses in various sites? Acta Cytol. 1989;33:809–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luse SA, Reagan JW. A histocytologic study of effusions: II, Effusions associated with malignant tumors. Cancer. 1954;7:1167–81. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195411)7:6<1167::aid-cncr2820070607>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandha VK, Vaidyanathan PS, Jagannatha PS, Unnikrishnan KP, Mini PA. Annual risk of tuberculosis infection in north zone of India. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:573–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandha VK, Jagannatha PS, Vaidyanathan PS, Singh S, Lakshminarayan Annual risk of tuberculosis infection in rural areas of UP, India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:528–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melamed MR. The cytological presentation of malignant lymphomas and related diseases in effusions. Cancer. 1963;16:413–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196304)16:4<413::aid-cncr2820160402>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foot NC. The identification of neoplastic cells in serous effusions. Am J Pathol. 1939;27:53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zemansky AP., Jr The examination of fluids for tumor cells: An analysis of 113 cases checked against subsequent examination of tissue. Am J M Sci. 1928;175:489–504. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlesinger J. Cytology of serous effusions effusions with special reference to tumor cells. Arch Surg. 1939;19:1672–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guenther H. Ceelen: The cytologic diagnosis of ascitic fluid. Acta Cytol. 1964;8:175–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taft PD, Kinish MJ, Naylor B. Cells of Squamous cell carcinoma in pleural, peritoneal and pericardial fluids: Origin and morphology. Acta Cytol. 1960;33:245–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maurice L, Perou AC. Malignant cells in serous effusions. AMA Arch Pathol. 1955;27:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg T, Hom BF. Studies on effusions II: A simple technique for the discovery of cancer cell in neoplastic exudates. Cancer. 1965;3:36–42. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<36::aid-cncr2820030107>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarah A, Ferri L. Scientia medica Italica. English edition. 1954. Modern methods for cytological diagnosis of pleural and pericardial effusions; pp. 68–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takagi F. Studies on tumor cells in serous effusion. Am J Clin Pathol. 1954;24:663–75. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/24.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson HL, Koss LG, Simon TR. Evaluation of concomitant use of cytological and histological technique in recognition of cancer in exfoliated material from various sources. Cancer. 1955;8:948–50. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1955)8:5<948::aid-cncr2820080515>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foord AG, Yongberg GE, Wetmore V. The Chemistry and cytology of serous fluids. J Lab Clin Med. 1929;14:417–28. [Google Scholar]