Abstract

Characterization of all chromosomes of the Andean G19833 bean genotype was carried out by fluorescent in situ hybridization. Eleven single-copy genomic sequences, one for each chromosome, two BACs containing subtelomeric and pericentromeric repeats and the 5S and 45S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) were used as probes. Comparison to the Mesoamerican accession BAT93 showed little divergence, except for additional 45S rDNA sites in four chromosome pairs. Altogether, the results indicated a relative karyotypic stability during the evolution of the Andean and Mesoamerican gene pools of P. vulgaris.

Keywords: common bean, repetitive DNA, chromosome marker, cytogenetic map, comparative map, intraspecific variation

The common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) is one of the main legume crops worldwide, with special dietary value for Latin America and Africa, where it represents a major source of proteins (Broughton et al., 2003). Despite its economical importance, genomic knowledge is still limited. Although full-genome sequences are available for such crops as rice (Goff et al., 2002) and grapevine (Jaillon et al., 2007), among warm-season legume crops, such as the common bean, only soybean has been sequenced so far (Schmutz et al., 2010).

Due to its distribution in the wild and two major domestication centers, P. vulgaris germplasm is comprised of two main gene-pools, the Andean and the Mesoamerican (Singh et al., 1991). The Mesoamerican breeding line BAT93, a parent of the main mapping population BAT93 x Jalo EEP558 (Freyre et al., 1998), has desirable characteristics, such as broad adaptation and disease resistance (Gepts et al., 2008). A large BAC library exists for this Mesoamerican cultivar (Kami et al., 2006) and clones from this library were used for establishing the cytogenetic map of the common bean integrated to its genetic maps (Pedrosa-Harand et al., 2009; Fonsêca et al., 2010). G19833, a Peruvian landrace, is a parent of the principal mapping population used at CIAT (Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical, Cali, Colombia), DOR364 x G19833 (Blair et al., 2003). Furthermore, Ramírez et al. (2005) developed expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from cDNA libraries of the Andean G19833 and the Mesoamerican variety ‘Negro Jamapa’. Recently, a G19833 BAC library was used for BAC-end sequencing and the development of a draft physical map of P. vulgaris (Schlueter et al., 2008). Currently, G19833 is also being sequenced by a group of US laboratories (S. Jackson, personal communication), thus showing the importance of G19833 for studies on the P. vulgaris genome structure, as well as for comparative studies in the Phaseolus genus (Gepts et al., 2008).

Several common bean accessions, including BAT93 and G19833, have been compared cytologically and they have shown large variation in the number and size of 45S rDNA loci (Pedrosa-Harand et al., 2006). Other repetitive sequences present in BAC inserts and localized in BAT93 (Pedrosa-Harand et al., 2009; Fonsêca et al., 2010) have not been analyzed in Andean accessions. Three out of four BACs defined for karyotyping in common bean contained repetitive sequences that may also vary in distribution between gene pools, hampering chromosome identification. Herein, the G19833 metaphase chromosomes were identified using single-copy probes previously mapped in BAT93, as a means of comparing chromosome distribution of repetitive sequences, and so contribute to G19833 genomic characterization.

Seeds of the P. vulgaris accession G19833 were obtained from the germplasm bank of the Embrapa Arroz e Feijão, Brazil. Root-tip pretreatment, fixation and storage, as well as mitotic chromosome preparation and the FISH procedure, have already been described by Fonsêca et al. (2010). Among the probes previously mapped in BAT93 (Pedrosa-Harand et al., 2009; Fonsêca et al., 2010), 10 single-copy BAC clones [221F15 (chromosome 1), 127F19 (chr. 2), 174E13 (chr. 3), 36H21 (chr. 5), 18B15 (chr. 6), 22I21 (chr. 7), 177I19 (chr. 8), 224I16 (chr. 9), 173P6 (chr. 10) and 255F18 (chr. 11)], one single-copy bacteriophage [B61 (chr. 4)], repetitive probes, such as a 5S (D2) and a 45S (R2) rDNA plasmid, a pericentromeric (12M3), and a subtelomeric (63H6) BAC, were all chosen for hybridization. All the selected clones were labeled by nick translation (Invitrogen or Roche) with either Cy3-dUTP (GE) or digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche). When necessary, either P. vulgaris C0t-1 or C0t-100 fractions, isolated according to Zwick et al. (1997), were added to the hybridization mixtures in 20-, 70- or 100-fold excess of probe concentration (5 ng/μL) to block repetitive sequences. FISH images were captured by an epifluorescence Leica DMLB microscope equipped with a Cohu CCD video camera using Leica QFISH software. Pictures were superimposed and artificially colored using the Adobe Photoshop software version 10.0 and adjusted for brightness and contrast. The BAT93 idiogram (Pedrosa-Harand et al., 2009; Fonsêca et al., 2010) was modified to schematically represent the differences observed in the G19833 chromosome complement. Chromosomes were named and oriented according to standard common bean nomenclature (Pedrosa-Harand et al., 2008).

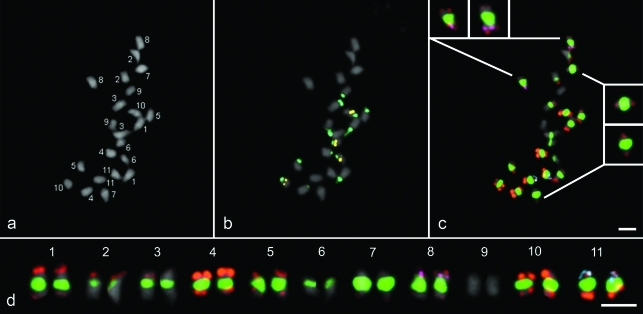

Each chromosome-specific marker identified one out of the eleven G19833 chromosome pairs (see, for example, BAC 177I19 in Figure 1a,c). Unlike BAT93 (Fonsêca et al., 2010), no additional signal was observed in chromosome 7 after hybridization with BAC 255F18 (Figure 1a,c), thereby confirming the absence of this repetitive block in the Andean accessions of the species (T.R.B. dos Santos, A. Fonsêca, K.G.B. dos Santos and A. Pedrosa-Harand, unpublished results). As for other species with chromosomes that are small and similar in morphology, such as the ones from common bean, BACs were essential for chromosome identification (Dong et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

FISH of repetitive and single-copy sequences in a metaphase of the Andean common bean accession G19833. a) Chromosomes counterstained with DAPI are numbered from 1 to 11, as identified by FISH; b) 5S (yellow) and 45S (dark green) rDNA loci; c) Clones 63H6 (subtelomeric; orange), 12M3 (pericentromeric; light green), 177I19 (chromosome 8; pink) and 255F18 (chromosome 11; blue). In inserts, chromosomes in a higher magnification showing hybridization signals of the subtelomeric clone 63H6; d) Karyogram. Bar in (c) and (d) represents 2.5 μm.

When blocking DNA was required in the hybridization mixture for BAT93, the same amount of C0t-100 was added to G19833 and comparable results were obtained. Various amounts of C0t-1 and C0t-100 were tested only for BAC 36H21. No or insufficient blocking was observed after the use of a 70- and 100-fold excess of C0t-1, although unique signals were still obtained when 70x C0t-100 was used, as was the case for BAT93 (data not shown). Due to different reassociation times in the production of C0t-1 and C0t-100 fractions, C0t-1 contains highly repetitive sequences only, whereas C0t-100 contains highly and moderately repetitive components of the genome (Zwick et al., 1997). This difference was visualized in tomato after the chromosomal localization of the C0t-1, C0t-10 and C0t-100 repetitive DNA fractions (Chang et al., 2008). FISH signals of labelled C0t fractions indicated 45S rDNA and telomere repeat predominance in C0t-1, whereas C0t-100 DNA signals were observed along all the chromosomes, except for certain interstitial and distal regions (Chang et al., 2008). The more effective blocking with C0t-100 confirmed the presence of moderately repetitive sequences in BAC 36H21. This blocking strategy is recommended for FISH experiments with BACs showing similar distribution patterns.

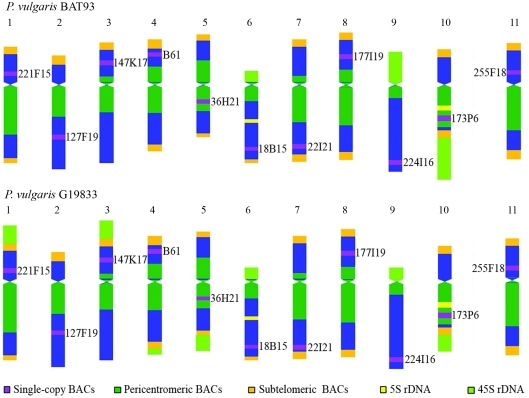

The sequential use of single-copy and repetitive BAC clones enabled the characterization of the G19833 karyotype, based on the distribution of subtelomeric and pericentromeric sequences in each chromosome pair. The hybridization patterns observed with the BACs 63H6 and 12M3 were similar to those described for BAT93 (Fonsêca et al., 2010). In chromosomes 1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10 and 11, signals from BAC 63H6 were apparent on both arms, with the strongest signals on chromosome 4. Chromosome 2 and 3 showed signals on the short arms only, the same occurring on the long arm of chromosome 6. Only chromosome 9 did not show any signal (Figure. 2). BAC 12M3 signals were detected in all the chromosomes, the weakest in chromosome 9 (Figure 2). As all the 11 chromosome pairs were identified with the same subset of only four BACs (Figure 1a,c), a karyogram showing all of them could be built (Figure 1d). The most pronounced difference from BAT93 was observed for chromosome 10, in that the signals from BAC 63H6 appeared to be more terminal on the long arm in the Andean cultivar. This results from the difference in size of the 45S rDNA site present at the end of this arm in both accessions.

Figure 2.

Distribution of repetitive sequences and localization of single-copy sequences on G19833 metaphase chromosomes counterstained with DAPI: subtelomeric (BAC 63H6; orange) and pericentromeric (BAC 12M3; light green) sequences; 45S (dark green) and 5S (yellow) rDNAs, as well as single-copy genomic clones (BACs and one bacteriophage; violet). Except for single-copy genomic clones, the chromosomes were obtained from one and the same metaphase, thus allowing for comparison of the intensity of hybridization signals. Scale bar represents 2.5 μm.

It was confirmed that the major karyotypic difference between these Andean and Mesoamerican gene pool accessions is related to the distribution of the 45S ribosomal DNA sites. In a previous analysis of 37 samples, between six and nine loci were detected in Andean accessions, whereas in Mesoamerican there were only three, rarely four 45S rDNA loci (Pedrosa-Harand et al., 2006). The number of 5S rDNA loci was conserved, with two loci per haploid genome (Figure 1b). In BAT93, only chromosomes 6, 9 and 10 bore 45S rDNA loci (Fonsêca et al., 2010), whereas in G19833, signals had previously been detected in seven chromosome pairs (Pedrosa-Harand et al., 2006). Through the identification of all the chromosomes in the present work, it was possible to recognize those bearing 45S rDNA, and thus characterize the respective chromosome-specific signal patterns. Chromosomes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9 and 10 carry 45S sequences more terminally than the subtelomeric sequences hybridized with BAC 63H6 (Figure 1b). The strongest signals were detected in chromosomes 1 and 3, with a gradual decrease in intensity in 5 and 10, followed by chromosomes 6 and 9, the weakest signal being detected in chromosome 4. Whereas, in chromosome pairs 4, 5 and 10, 45S rDNA loci were on the long arm, in 1, 3, 6 and 9, these were on the short arm. Contrary to BAT93, the 45S rDNA signal detected in chromosome 10 of G19833 seems to be weaker than that in chromosome 6 (Figure 1b). By using the idiogram developed for BAT93 (Fonsêca et al., 2010), a schematic representation of G19833 chromosomes, showing the approximate distribution of repetitive sequences and chromosome markers, was established (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Modified idiogram of BAT93 (Pedrosa-Harand et al, 2009; Fonsêca et al., 2010) and schematic representation of G19833 chromosomes, showing the distribution patterns of repetitive sequences. Approximate positions of chromosome markers are also indicated.

Altogether, a comparison between the present results for G19833 and previous ones for BAT93 (Fonsêca et al., 2010) revealed only a slight karyotypic divergence between these accessions, mainly restricted to the 45S rDNA loci, thereby implying relative stability in the distribution of pericentromeric and subtelomeric repeats among the Andean and Mesoamerican lineages during evolution. Therefore, despite the variation observed for BAC 255F18, the chromosomes of G19833 could be differentiated using the same set of BACs previously used for chromosome identification in BAT93. The combination of nine tandemly repeated DNA sequences as probes also facilitated identification of all the maize chromosome pairs in 14 lines, although more pronounced differences in the distribution of knob, microsatellite, centromeric and subtelomeric sequences were observed among these maize accessions (Kato et al., 2004) than between the common bean accessions analyzed here. The identification of all the G19833 chromosomes could be useful in further analyses of the genomic structure of this Andean common bean.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank James Kami and Paul Gepts (University of California) for providing the BAC clones, Valérie Geffroy for providing the bacteriophage, EMBRAPA Arroz e Feijão for supplying the seeds, and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil, for financial support.

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Angela M. Vianna-Morgante

References

- Blair MW, Pedraza F, Buendia HF, Gaitán-Solís E, Beebe SE, Gepts P, Tohme J. Development of a genome-wide anchored microsatellite map for common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2003;107:1362–1374. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton WJ, Hernandez G, Blair M, Beebe S, Gepts P, Vanderleyden J. Beans (Phaseolus spp.) - Model food legumes. Plant Soil. 2003;252:55–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chang S-B, Yang T-J, Datema E, van Vugt J, Vosman B, Kuipers A, Meznikova M, Szinay D, Klein Lankhorst R, Jacobsen E, et al. FISH mapping and molecular organization of the major repetitive sequences of tomato. Chromosome Res. 2008;16:919–933. doi: 10.1007/s10577-008-1249-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F, Song J, Naess SK, Helgeson JP, Gebhardt C, Jiang J. Development and applications of a set of chromosome-specific cytogenetic DNA markers in potato. Theor Appl Genet. 2000;101:1001–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Fonsêca A, Ferreira J, dos Santos TRB, Mosiolek M, Bellucci E, Kami J, Gepts P, Geffroy V, Schweizer D, dos Santos KGB, et al. Cytogenetic map of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Chromosome Res. 2010;18:487–502. doi: 10.1007/s10577-010-9129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyre R, Skroch PW, Geffroy V, Adam-Blondon AF, Shirmohamadali A, Johnson WC, Llaca V, Nodari RO, Pereira PA, Tsai SM, et al. Towards an integrated linkage map of common bean: 4. Development of a core linkage map and alignment of RFLP maps. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;97:847–856. [Google Scholar]

- Gepts P, Aragão FJL, de Barros E, Blair MW, Brondani R, Broughton W, Galasso I, Hernández G, Kami J, Lariguet P, et al. Genomics of Phaseolus beans, a major source of dietary protein and micronutrients in the tropics. In: Moore PH, Ming R, editors. Genomics of Tropical Crop Plants. Springer; Berlin: 2008. pp. 113–143. [Google Scholar]

- Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan T-H, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, Glazebrook J, Sessions A, Oeller P, Varma H, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. spp. japonica) Science. 2002;296:92–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O, Aury JM, Noel B, Policriti A, Clepet C, Casagrande A, Choisne N, Aubourg S, Vitulo N, Jubin C, et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kami J, Poncet V, Geffroy V, Gepts P. Development of four phylogenetically-arrayed BAC libraries and sequence of the APA locus in Phaseolus vulgaris. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;112:987–998. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato A, Lamb JC, Birchler JA. Chromosome painting using repetitive DNA sequences as probes for somatic chromosome identification in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13554–13559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403659101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-S, Klein PE, Klein RR, Price HJ, Mullet JE, Stelly DM. Chromosome identification and nomenclature of Sorghum bicolor. Genetics. 2005;169:1169–1173. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.035980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa-Harand A, de Almeida CCS, Mosiolek M, Blair MW, Schweizer D, Guerra M. Extensive ribosomal DNA amplification during Andean common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) evolution. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;112:924–933. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa-Harand A, Porch T, Gepts P. Standard nomenclature for common bean chromosomes and linkage groups. Annu Rep Bean Improv Coop. 2008;51:106–107. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa-Harand A, Kami J, Gepts P, Geffroy V, Schweizer D. Cytogenetic mapping of common bean chromosomes reveals a less compartmentalized small-genome plant species. Chromosome Res. 2009;17:405–417. doi: 10.1007/s10577-009-9031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez M, Graham MA, Blanco-López L, Silvente S, Medrano-Soto A, Blair MW, Hernández G, Vance CP, Lara M. Sequencing and analysis of common bean ESTs. Building a foundation for functional genomics. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:1211–1227. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.054999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter JA, Goicoechea JL, Collura K, Gill N, Lin JY, Yu Y, Kudma D, Zuccolo A, Vallejos CE, Muñoz-Torres M, et al. BAC-end sequence analysis and a draft physical map of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genome. Trop Plant Biol. 2008;1:40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J, Cannon SB, Schlueter J, Ma J, Mitros T, Nelson W, Hyten DL, Song Q, Thelen JJ, Cheng J, et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463:178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Gepts P, Debouck DG. Races of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L., Fabaceae) Econ Bot. 1991;45:379–396. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Guan B, Guo W, Zhou B, Hu Y, Zhu Y, Zhang T. Completely distinguishing individual A-genome chromosomes and their karyotyping analysis by multiple bacterial articial chromosome-fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genetics. 2008;178:1117–1122. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwick MS, Hanson RE, McKnight TD, Islam-Faridi MH, Stelly DM, Wing RA, Price HJ. A rapid procedure for isolation of C0t-1 DNA from plants. Genome. 1997;40:138–142. doi: 10.1139/g97-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]