Abstract

Regulated proteolysis of Cactus, the cytoplasmic inhibitor of the Rel-related transcription factor Dorsal, is an essential step in patterning of the Drosophila embryo. Signal-induced Cactus degradation frees Dorsal for nuclear translocation on the ventral and lateral sides of the embryo, establishing zones of gene expression along the dorsoventral axis. Cactus stability is regulated by amino-terminal serine residues necessary for signal responsiveness, as well as by a carboxy-terminal PEST domain. We have identified Drosophila casein kinase II (CKII) as a Cactus kinase and shown that CKII specifically phosphorylates a set of serine residues within the Cactus PEST domain. These serines are phosphorylated in vivo and are required for wild-type Cactus activity. Conversion of these serines to alanine or glutamic acid residues differentially affects the levels and activity of Cactus in embryos, but does not inhibit the binding of Cactus to Dorsal. Taken together, these data indicate that wild-type axis formation requires CKII-catalyzed phosphorylation of the Cactus PEST domain.

Keywords: proteolysis, Rel, NF-κB, signal transduction, Dorsal

A nuclear concentration gradient of the transcription factor Dorsal defines the dorsoventral axis of the Drosophila embryo (for review, see Chasan and Anderson 1993). Dorsal is a member of the Rel family of proteins that includes mammalian NF-κB, the avian oncogene v-rel, and the cellular proto-oncogene c-rel (Steward 1987; for review, see Verma et al. 1995). Transcriptional activity of Rel proteins is controlled at the level of subcellular localization. More specifically, ankyrin-repeat containing inhibitory proteins such as Cactus, IκBα, and IκBβ retain Rel proteins in the cytoplasm by direct interaction. On stimulation, signal transduction targets the inhibitors for degradation, freeing the Rel-proteins for translocation into nuclei.

A maternally encoded signal transduction pathway directs the asymmetric nuclear translocation of Dorsal in the embryo (for review, see Chasan and Anderson 1993). A protease cascade active in the ventral portion of the extraembryonic space cleaves, and thereby activates, the Spätzle protein. Spätzle then acts as an extracellular ligand, binding the transmembrane receptor Toll. This asymmetric activation of Toll initiates intracellular signal transduction via the protein kinase Pelle that drives Cactus degradation, thereby freeing Dorsal for nuclear import. On translocation into ventral and lateral nuclei, Dorsal establishes embryonic polarity by activating transcription of ventral-specific genes while repressing dorsal-specific loci.

The pathway governing subcellular localization of Drosophila Dorsal displays striking similarities to at least one pathway that controls the partitioning of mammalian NF-κB between the nucleus and cytoplasm (Wasserman 1993; Cao et al. 1996). At least four of the proteins in the Drosophila dorsoventral pathway—Toll, Pelle, Dorsal, and Cactus—have structural and functional counterparts in the response of lymphocytes and other cell types to the cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1)—the IL-1 receptor, the IL-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK), NF-κB, and IκBα.

In both the invertebrate and vertebrate Rel-protein pathways, phosphorylation of the inhibitor appears to be a critical step in signal transduction (for review, see Baeuerle and Baltimore 1996). Signal-dependent degradation of IκBα requires phosphorylation of a pair of serine residues, followed by IκBα ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation (Palombella et al. 1994; Brown et al. 1995; Traenckner et al. 1995). Signal transduction to Cactus requires two pairs of serine residues in a similar sequence context; mutation of these four serines to alanines blocks signal-mediated degradation of Cactus (Reach et al. 1996).

The structural and functional similarities between Cactus and IκBα extend to their carboxyl termini. Both proteins contain a carboxy-terminal PEST sequence. Such domains, rich in proline (P), glutamate (E), serine (S), and threonine (T) residues, are thought to induce rapid protein turnover (Rogers et al. 1986; Rechsteiner and Rogers 1996). Consistent with this hypothesis, deletion of the PEST-containing region from IκBα leads to a substantial increase in steady-state protein levels (Lin et al. 1996; Van Antwerp and Verma 1996). PEST-deleted forms of both Cactus and IκBα are still rapidly degraded in response to signaling, but the efficiency of signal transduction is reduced (Belvin et al. 1995; Baeuerle and Baltimore 1996; Bergmann et al. 1996; Reach et al. 1996). It is not known whether this diminution in signaling results solely from an increase in the number of inhibitor molecules to be degraded or as well as from a change in the responsiveness of individual molecules to the signaling apparatus.

In the course of investigating Cactus regulation, we have purified a kinase that specifically phosphorylates the PEST region of Cactus. We have identified this kinase as Drosophila casein kinase II (CKII) and have mapped the phosphorylation sites to a group of three serines. We have shown that these Cactus PEST domain serines are phosphorylated in embryos. We have also explored the effect of mutating these serines on signal transduction to the Dorsal–Cactus complex, on Cactus binding to Dorsal, and on the levels of Cactus in embryos. Taken together, our results indicate that CKII phosphorylation of Cactus is required for efficient signaling to the Dorsal–Cactus complex and that phosphorylation modulates PEST-mediated protein degradation in vivo.

Results

An in-gel assay detects Drosophila CKII as a Cactus kinase

Cactus is a phosphoprotein in the developing embryo and protein kinase activity is required in the signaling pathway that governs Cactus degradation (Kidd 1992; Shelton and Wasserman 1993). To identify the kinase(s) responsible for phosphorylation of Cactus in embryos, we performed an in-gel assay (Hibi et al. 1993). We prepared extracts from 0- to 3-hr embryos and subjected them to electrophoresis in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel containing hexahistidine-tagged Cactus (His6–Cactus) incorporated into the gel matrix. Following electrophoresis, resolved proteins were allowed to renature and were then assayed for phosphotransferase activity in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP.

The in-gel Cactus kinase assay revealed a single radiolabeled species with an apparent molecular weight (mw) of 37,000 (Fig. 1A,B). No radiolabeled band was detected when His6–Cactus was omitted from the gel matrix (data not shown), showing that Cactus, and not the kinase itself, was the substrate for the in-gel activity. The in-gel activity was independent of the embryonic signaling state; we obtained identical results by use of extracts from embryos in which the signaling pathway was inactive (gd2/gd2), active only ventrally (wild-type), or constitutively active (Tl10b).

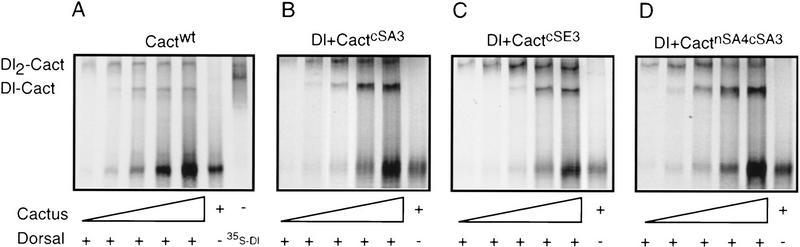

Figure 1.

In-gel kinase assay allows identification and purification of a Cactus kinase in embryonic extracts. (A) Coomassie-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel loaded with 20 μg of total embryonic protein from gd2 (lane 1), wild-type (lane 2), and Tl10b (lane 3). (B) In-gel kinase assay. Embryonic proteins corresponding to those in the Coomassie-stained gel were subjected to electrophoresis and a subsequent in-gel kinase assay in an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel that was polymerized in the presence of 40 μg/ml of His6–Cactus. The [32P]-labeled proteins were then visualized by autoradiography. The sizes of the molecular mass markers between the panels are in kilodaltons. The arrow indicates the position of a Cactus kinase activity (37,000 mw). (C) Coomassie-stained SDS–polyacrylamide gel of fractions from the purification of Cactus kinase CKII. (Lane 1) mw markers; (lanes 2–4) 20 μg of protein; (lane 5) 3 μg of protein; (lane 6) 2 μg of protein. (D) In-gel kinase assay with half as much protein per lane as in the Coomassie-stained gel shown in C.

By use of extracts from 0- to 16-hr wild-type embryos as the kinase source and GST–Cactus as the substrate, we developed a three-step procedure for purifying the Cactus kinase to >95% homogeneity (Fig 1C). The purified kinase has 28,000 and 37,000 mw subunits, of which only the latter has detectable kinase activity (Fig. 1D). Amino-terminal protein sequencing of the catalytically active kinase subunit revealed that the first 15 residues were identical to those of the 37,000 mw catalytic, or α, subunit of CKII (Saxena et al. 1987). The apparent mw (28,000) of the other subunit in our preparation matches that of the regulatory, or β, subunit of CKII. Furthermore, the Cactus kinase activity and the two enzyme subunits elute from a gel filtration column with an apparent mw of 130,000 (data not shown), consistent with the previous finding that native CKII is an α2β2 tetramer (Glover et al. 1983).

CKII phosphorylates serine residues in the Cactus PEST domain

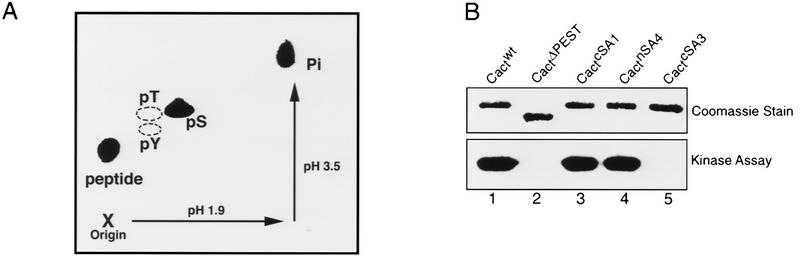

CKII can modify both serine and threonine residues. To identify which side chains in Cactus are phosphorylated by CKII, we incubated a Cactus fusion protein with the purified kinase in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP and then carried out two-dimensional phosphoamino acid analysis. As shown in Figure 2A, CKII phosphorylates GST–Cactus exclusively at serine residues.

Figure 2.

Mapping the phosphorylation sites in Cactus. (A) Phosphoamino acid analysis of Cactus protein phosphorylated in vitro with partially purified CKII. Standards [(pS) phosphoserine; (pT) phosphothreonine; (pY) phosphotyrosine] were visualized by ninhydrin stain; 32P-labeled amino acids were detected by autoradiography. The positions of free phosphate, partially digested polypeptides, and the sample origin are indicated. (B) GST-tagged wild-type and mutant Cactus isoforms (∼200 ng each) were used as substrates in in vitro kinase assays with purified CKII. Total protein was stained (top) before being visualized by autoradiography (bottom). (C) Schematic representation of Cactus. Numbers indicate position in the amino acid sequence. Amino acid substitutions in each Cactus mutant are indicated by the dashed lines.

In determining which serine residues in Cactus were the sites of CKII phosphorylation, we began by carrying out deletion mapping in combination with a liquid-phase kinase assay. These experiments revealed that CKII fails to phosphorylate a Cactus protein lacking amino acids 458–501 (Fig. 2B, lane 2). This truncated Cactus protein, referred to as CactΔPEST, lacks the PEST domain, as well as 24 residues carboxy-terminal to this domain (Fig. 2C).

Next, we used site-directed mutagenesis to determine whether CKII phosphorylation occurred specifically within the PEST domain. Four serine residues lie within the region deleted in the CactΔPEST protein; three of these lie within the PEST domain itself (Fig. 2C). In generating the cactcSA3 construct, we mutated the codons encoding the PEST domain serines (Ser-463, Ser-467, and Ser-468), converting these three residues to alanines. We mutated Ser-490, carboxy-terminal to the PEST domain, independently, to produce cactcSA1. The cSA3 mutation blocked Cactus phosphorylation by CKII in vitro, whereas the cSA1 mutation had no detectable effect (Fig. 2B, lanes 3,5). Thus, CKII phosphorylation of Cactus in vitro is restricted to the three serines, or a subset thereof, within the Cactus PEST domain. Two of these serines, Ser-463 and Ser-468, lie within a consensus CKII phosphorylation site: S/T X X D/E, in which X represents any nonbasic amino acid (Pinna 1990).

The Cactus PEST domain CKII sites are phosphorylated in vivo

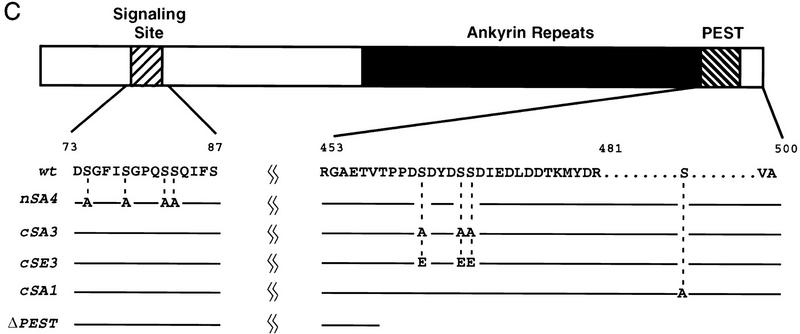

Next, we investigated whether the CKII sites in the Cactus PEST domain are phosphorylated in developing embryos. By comparing the ability of CKII to phosphorylate untreated and phosphatase-treated Cactus from embryos, we could specifically assay to what extent the Cactus CKII sites were modified in vivo.

Immunoprecipitates from embryonic extracts were incubated with or without alkaline phosphatase (CIP), then treated with purified CKII in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. We subjected the reaction products to electrophoresis in an SDS–polyacrylamide gel, transferred the resolved proteins to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and used the membrane for immunoblotting with anti-Cactus antibodies (Fig. 3A) and for autoradiography (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

The CKII sites are phosphorylated in vivo. The immunocomplexes generated with anti-Dorsal serum and 5 mg of 0–3 hr wild-type or gd2 embryonic extracts were incubated with (lanes 3,4,6) or without (lanes 1,2,5) calf alkaline phosphatase (CIP). The immunoprecipitates were then washed with kinase buffer and further incubated in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP with (lanes 2,4,5,6) or without (lanes 1,3) purified CKII. The resolved proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane for immunoblotting with anti-Cactus antibodies (top) and autoradiography (bottom).

Cactus protein from wild-type embryos was phosphorylated by CKII to an appreciable extent only after phosphatase treatment (Fig. 3B, lanes 2,4). The same was true for Cactus from gd2 embryos (Fig. 3B, lanes 5,6). We conclude that most, if not all, Cactus in embryos is phosphorylated at the CKII sites, regardless of the state of the dorsoventral signaling pathway.

The experiments presented in Figure 3 also provided evidence that CKII is not the only Cactus kinase in embryos. Phosphatase treatment increased the electrophoretic mobility of embryonic Cactus protein (Fig. 3A, lanes 1,2 vs. lanes 3,4), yet phosphorylation of Cactus by CKII did not substantially counteract this effect (Fig. 3A, lanes 2,4). Thus, Cactus is phosphorylated in vivo at one or more sites other than the sites of CKII modification. In this regard, we have previously identified four serine residues in the amino terminus of Cactus as the probable sites of signal-inducible phosphorylation (Reach et al. 1996).

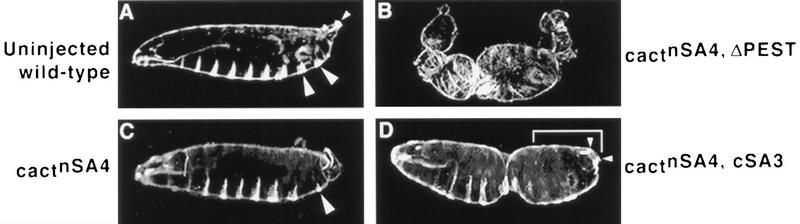

Mutation of the CKII phosphorylation sites alters Cactus function in vivo

Next, we used an RNA microinjection assay to ascertain whether the CKII phosphorylation sites in the Cactus carboxyl terminus influence dorsoventral patterning. Mutant forms of Cactus expressed from microinjected RNA can compete with endogenous Cactus and inhibit signaling (Belvin et al. 1995; Bergmann et al. 1996; Reach et al. 1996). Such inhibition prevents Dorsal nuclear translocation, resulting in a dorsalization that reflects a loss of ventral and lateral fates and an expansion of dorsal ones. This change in cell fates is apparent both as a decrease in the percentage of embryos that hatch into larvae and as an alteration in the cuticle of the unhatched embryos.

Four degrees of dorsalization can be distinguished by examining the cuticle of unhatched embryos (Roth et al. 1991; Chasan and Anderson 1993). A D3 cuticle, the most mildly affected, has wild-type elements, but is curled up on itself because of a partial loss of the ventrally derived mesoderm. The more severely affected D2 and D1 cuticles are characterized by a reduction or loss, respectively, of the ventral denticle belts. The absence of signal transduction results in a completely dorsalized or D0 cuticle, a twisted tube of epidermis lacking not only the ventral denticle belts but also the dorsolaterally derived Filzkörper.

RNAs corresponding to CactcSA3 were injected into the posterior end of wild-type stage 2 embryos, prior to the initiation of intracellular dorsoventral signaling. Forty-two percent of the injected embryos failed to hatch and many of these exhibited a D3 phenotype (Table 1). In contrast, microinjection of cactwt RNA had no detectable effect on viability, as evidenced by a hatch rate equivalent to that of embryos injected with buffer alone (94% vs. 90%; Table 1). Thus, a Cactus protein mutant for the three PEST domain serines decreased the efficiency of signaling to Dorsal in the embryo.

Table 1.

Phenotypic effects of wild-type and mutant cactus RNA injected into wild-type embryos

| RNA injected

|

Embryos hatched (%)

|

Extent of dorsalization

|

Embryos scored (no.)

|

|---|---|---|---|

| none | 90 | none | 42 |

| cactwt | 94 | none | 63 |

| cactcSA3 | 58 | D3 | 53 |

| cactΔPEST | 0 | D2 | 48 |

| cactnSA4 | 30 | D2 | 130 |

| cactnSA4, cSA3 | 3 | D1 | 118 |

| cactcSE3 | 87 | none | 55 |

| cactnSA4, cSE3 | 73 | D3 | 112 |

RNA transcripts were produced in vitro and injected at a concentration of 2 μg/μl into stage-2 embryos obtained from wild-type females. For nonhatching larvae, a subset of cuticles were obtained and examined around the site of microinjection; the extent of dorsalization represents the most severe phenotype detected. (cactwt) Wild-type cactus.

The phenotypic consequence of mutating the CKII sites in the Cactus PEST domain, although significant, was less severe than the effect of deleting the PEST region altogether. Parallel injection experiments carried out with cactΔPEST RNA resulted in a 0% hatch rate and a D2 phenotype (Table 1). Thus, as noted previously (Belvin et al. 1995; Bergmann et al. 1996), Cactus lacking the PEST domain interferes substantially with dorsoventral signaling in a wild-type embryo.

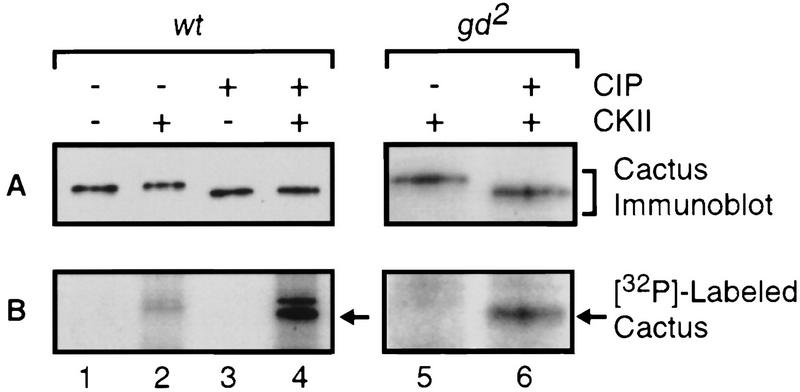

The function of the PEST domain CKII sites is distinct from that of the signal acceptor sites in the Cactus amino terminus

To compare further the effect of mutating the Cactus CKII sites with deletion of the Cactus PEST domain, we combined the cSA3 and ΔPEST mutations with the amino-terminal SA4 mutation, in which Ser-74, Ser-78, Ser-82, and Ser-83 are converted to alanines (Fig. 2C). We have shown previously that this mutation, hereafter termed nSA4, blocks signal-mediated degradation of Cactus (Reach et al. 1996).

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 4, the cSA3 mutation significantly enhanced the dominant-negative effect of nSA4 on dorsoventral signaling. By itself, the nSA4 mutation reduced the hatch rate of injected embryos in this assay threefold (Table 1) and resulted in phenotypes as severe as D2 (Fig.4, cf. C to A). In contrast, the cactnSA4,cSA3 double mutant lowered the hatch rate an additional 10-fold relative to wild-type and resulted in D1 cuticles (Fig. 4D). As in the single-mutant studies, however, the cSA3 mutation had a less severe effect than did deletion of the entire PEST domain. Microinjection of cactnSA4,ΔPEST RNA resulted in D0 cuticles lacking all ventral denticle belts as well as the Filzkörper (Fig. 4B). These results show that CKII-mediated phosphorylation contributes to, but is not a strict prerequisite for, Cactus PEST domain function.

Figure 4.

Mutation of the sites necessary for CKII phosphorylation of Cactus in vitro alters Cactus activity in vivo. Darkfield micrographs are shown of cuticles (anterior left; ventral bottom) derived from uninjected wild-type embryos (A) or wild-type embryos injected with 2 mg/ml of RNA at the posterior end (B–D). (A) No RNA. Eight abdominal ventral denticlebelts are evident (the two posterior-most denticle belts are highlighted by the large arrowheads), as is the dorsolaterally derived Filzkörper apparatus at the posterior end (small arrowhead). (B) cactnSA4,ΔPEST RNA. Complete dorsalization (D0 phenotype) is apparent, with all ventral and lateral cuticle elements missing. (C) cactnSA4 RNA. One of the two posterior-most ventral denticle belts is absent with the remaining belt significantly reduced in size (large arrowhead; D2 phenotype). (D) cactnSA4,cSA3 RNA. The posterior ventral denticle belts are missing from the cuticle (delineated by the white bracket), but the Filzkörper are present (small arrowheads; D1 phenotype).

Glutamate substitutions in the CKII sites suppress the dominant inhibitory effect of cactnSA4

A reasonable interpretation of our results is that the serine-to-alanine substitutions in CactcSA3 block phosphorylation by CKII and thereby alter the activity of Cactus in vivo. If so, conversion of the PEST domain serines to glutamate residues might affect Cactus in an altogether different manner. Although the glutamic acid side chains would block phosphorylation by CKII, their negative charge might serve as a mimetic replacement for the phosphate groups introduced into wild-type Cactus by CKII. Therefore, we generated the cactcSE3 construct, in which codons 463, 467, and 468 encode glutamic acid residues.

By itself, cactcSE3 RNA did not interfere with signaling (Table 1). Embryos injected with cactcSE3 RNA had a hatch rate (87%) comparable with that observed for embryos injected with buffer alone (90%). Thus, as predicted, CactcSE3 behaved much more like wild-type Cactus than like CactcSA3.

When combined with nSA4, the cSE3 mutation differed in phenotype not only from the nSA4,cSA3 double mutant but also the nSA4 single mutant. Only about one-fourth of the embryos injected with cactnSA4,cSE3 RNA failed to hatch and none exhibited a phenotype more severe than D3 (Table 1). Thus, the cSE3 mutation suppressed the nSA4 phenotype.

Mutation of the CKII phosphorylation sites in Cactus does not alter association with Dorsal

The fact that CactcSA3 is similar in phenotype to CactΔPEST suggested that CKII-mediated phosphorylation of Cactus enhances PEST-mediated protein turnover. Nonetheless, it remained possible that modification of the CKII sites in CactcSA3 altered the interaction of Cactus with Dorsal. Therefore, we used proteins translated in vitro to assay the binding of wild-type and mutant Cactus isoforms to Dorsal.

Approximately 10 fmoles of unlabeled Dorsal protein was mixed with varying amounts of 35S-labeled Cactus isoforms and the resulting complexes separated on 5% native polyacrylamide gels. When four fmoles of 35S-Cactus was added to the binding reaction, we detected two radiolabeled species (Fig. 5A). The faster migrating species consisted of free Cactus. The slower migrating complex contained Dorsal as well as Cactus, as confirmed by immunoblot experiments with anti-Dorsal antibodies and by a parallel protein association assay with 35S-labeled Dorsal and unlabeled Cactus (data not shown). On the basis of the pI of each protein and the mobility of Dorsal monomers and dimers (Fig. 5A), we deduced that the slower migrating species contained two Dorsal molecules and one Cactus (Dl2–Cact). Such a complex has been detected in embryos (Isoda and Nüsslein-Volhard 1994), where the ratio of Cactus to Dorsal is comparable with that used here.

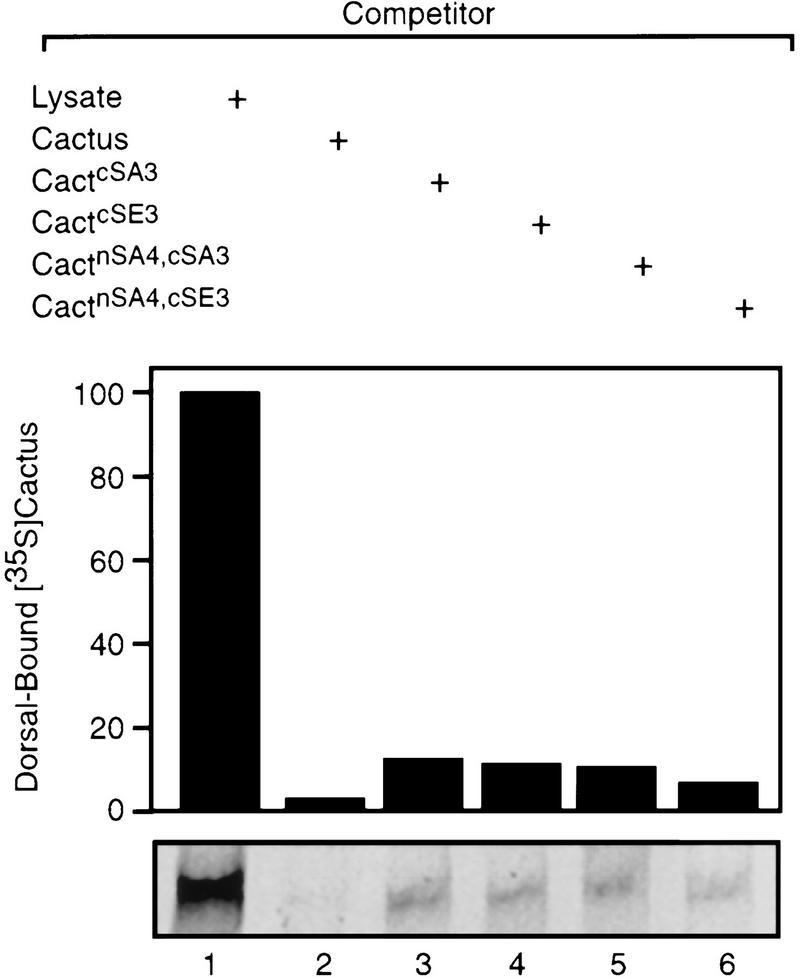

Figure 5.

Association of Dorsal with wild-type and mutant Cactus. A constant amount of unlabeled Dorsal was mixed with increasing amounts of 35S-labeled Cactwt (A), CactcSA3 (B), CactcSE3 (C), and CactnSA4,cSA3 (D). Bands corresponding to free Cactus and two Dorsal–Cactus complexes are indicated. The mobility of 35S-labeled Dorsal species resolved in the absence of Cactus is shown in the extra lane in A.

When we added more Cactus to the binding assay, we detected increasing amounts of a third species that contained both Dorsal and Cactus. This species had a mobility greater than that of Dl2–Cact, but still appreciably slower than that of free Cactus. Therefore, we believe that this species contains one molecule each of Dorsal and Cactus (Dl–Cact).

The wild-type and mutant forms of Cactus exhibited similar affinities for Dorsal. Cactus isoforms in which the three serines in the PEST domain had all been mutated to either alanine (CactcSA3) or glutamate (CactcSE3) bound Dorsal to the same extent as wild-type Cactus (Fig. 5B,C). The same was true for CactnSA4,cSA3 (Fig. 5D).

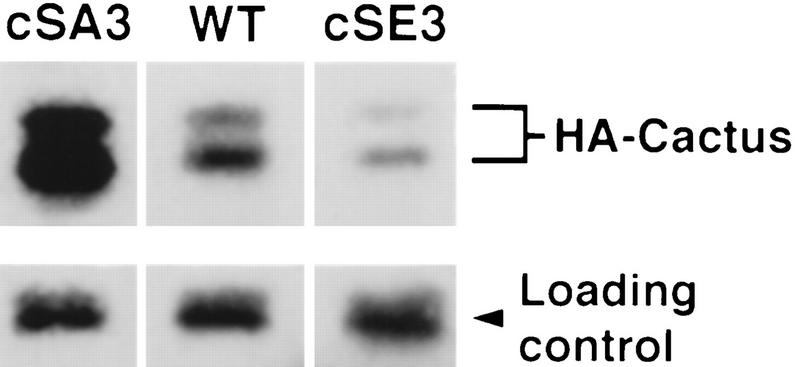

The mutant Cactus proteins also displayed wild-type activity in a competition assay (Fig. 6). In these experiments, Dorsal association with labeled Cactus was initiated in the presence of a 20-fold excess of an unlabeled Cactus isoform. Wild-type and mutant Cactus proteins did not differ significantly in their ability to compete with 35S-labeled wild-type Cactus for binding to Dorsal (Fig. 6). We conclude that modification of the CKII sites in the Cactus PEST region does not appreciably affect the association of Cactus with Dorsal.

Figure 6.

Competition between Dorsal-bound wild-type 35S-labeled Cactus and mutated Cactus proteins. Ten femtomoles of unlabeled Dorsal and 10 fmoles of 35S-labeled wild-type Cactus were mixed with reticulocyte lysate alone (lane 1) or with lysate containing a 20-fold excess of Cactwt (lane 2), CactcSA3 (lane 3), CactcSE3 (lane 4), CactnSA4,cSA3 (lane 5), or CactnSA4,cSE3 (lane 6). The amounts of Dorsal-bound Cactus were visualized by autoradiography (bottom) and quantitated to construct the bar graph (arbitrary units).

Mutation of the CKII phosphorylation sites alters Cactus protein levels in vivo

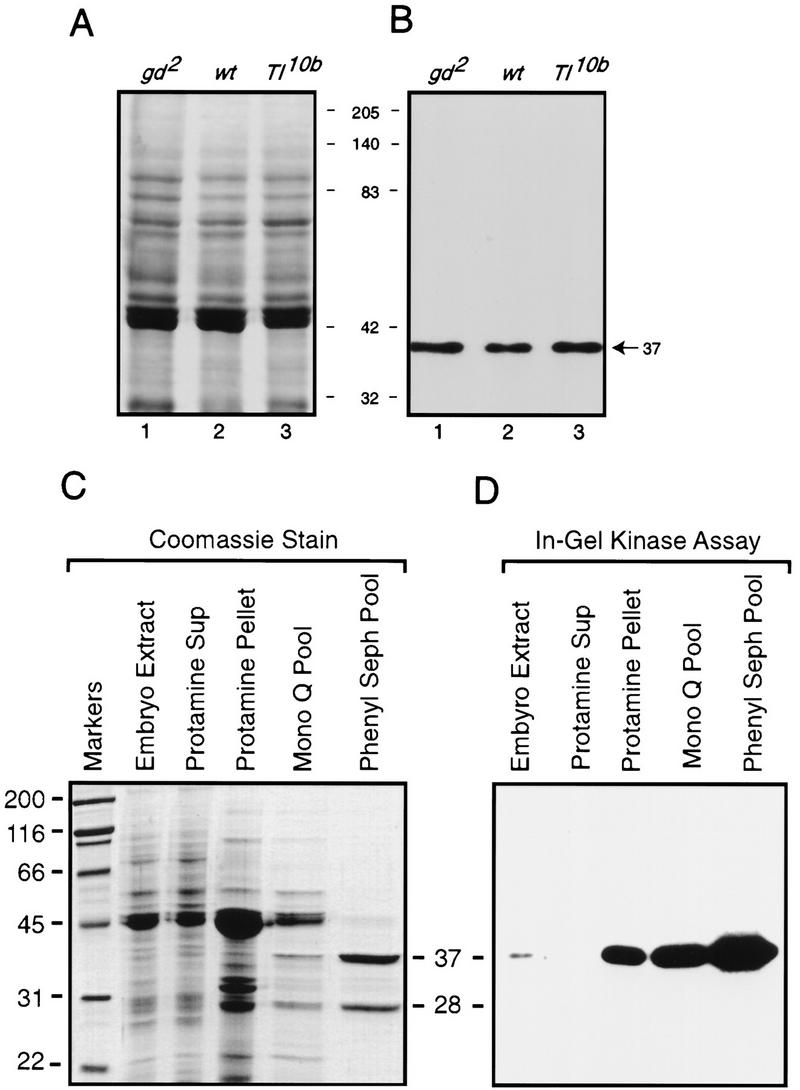

Having found that Cactwt, CactcSA3, and CactcSE3 bound Dorsal with comparable affinities, we set out to directly assay whether the cSA3 and cSE3 mutations altered Cactus accumulation in vivo. We generated RNA by transcription in vitro of HA-tagged versions of cactwt, cactcSA3, or cactcSE3, injected these RNAs into stage 2 embryos, and allowed development to continue until stage 4. We then extracted total embryonic contents with a microinjection needle and analyzed the levels of the hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Cactus isoforms by immunoblotting.

As shown in Figure 7, HA–CactcSA3 accumulated to a substantially higher level than HA–Cactwt, whereas much less HA–CactcSE3 was present than the wild-type isoform. Thus, there was a close correlation in vivo between the activity and amount of the three Cactus isoforms. These results provide strong support for the hypothesis that phosphorylation of Cactus by CKII enhances PEST domain function in promoting protein turnover.

Figure 7.

The cSA3 and cSE3 mutations affect Cactus protein levels in vivo. Wild-type stage 2 embryos were microinjected with the indicated HA-tagged cactus-encoding RNA and allowed to develop to stage 4. Total embryonic extracts were then collected by microextraction and examined by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. The membrane was then immediately reprobed for a biotinylated embryonic protein to control for loading (Reach et al. 1996). Two isoforms of HA–Cactus are visible, as also observed for endogenous Cactus (Belvin et al. 1995; Reach et al. 1996).

Discussion

Wild-type activity of the Cactus PEST domain in embryos requires phosphorylation by CKII

We have shown that Drosophila CKII phosphorylates Cactus in vitro and that Cactus is phosphorylated in vivo at the CKII sites at the time of dorsoventral signaling. We conclude that CKII phosphorylates the Cactus PEST domain in embryos, while recognizing that a definitive proof of this hypothesis awaits isolation and characterization of CKII mutations. We also find evidence for phosphorylation of Cactus at other sites, consistent with our previous findings (Reach et al. 1996). Our failure to detect additional Cactus kinases in the in-gel assay may indicate that such kinases are much less abundant than CKII, that they are only active as multimers, or that they fail to recognize bacterially expressed Cactus as a substrate.

CactΔPEST and CactcSA3, but not wild-type Cactus or CactcSE3, interfered with signaling when introduced into wild-type embryos. We, and others, have shown previously that CactΔPEST accumulates at the expense of wild-type Cactus (Belvin et al. 1995; Reach et al. 1996); here we have shown that the cSA3 mutation also leads to higher levels of Cactus in embryos, whereas the cSE3 reduces the amount of protein that accumulates. Neither substitution mutation, however, disrupts the binding of Cactus to Dorsal.

We interpret these experiments as follows: Cactus protein deleted for the PEST domain (CactΔPEST) or lacking the negative charges introduced by CKII-mediated phosphorylation (CactcSA3) has a longer half-life than endogenous Cactus. As a result, Cactus accumulates above wild-type levels, interfering with signal transduction. In contrast, exogenous wild-type Cactus, like the endogenous protein, is efficiently degraded and, consequently, has no effect on signaling. Cactus in which the PEST domain is not phosphorylated but is nonetheless negatively charged (CactcSE3) is also efficiently degraded and does not, therefore, alter Dorsal gradient formation.

We believe that differential effects on PEST function also underlie the enhancement of nSA4 seen with ΔPEST and cSA3, as well as the suppression observed with cSE3. In the experiments described here, the relative half-lives of wild-type Cactus and Cactus mutant for the nSA4 site determined the degree of dorsalization. As a result, the dominant interfering activity of CactnSA4 was increased by the mutations blocking PEST-mediated turnover and decreased by the glutamate substitutions that apparently promote PEST-dependent proteolysis.

Given that the sites of CKII phosphorylation are occupied in vivo, it may seem paradoxical that substitution of glutamic acid residues for the three PEST domain serines increases PEST-mediated proteolysis. A likely explanation is that the cSE3 mutation acidifies the PEST domain to a greater extent than does CKII-mediated phosphorylation. Only two of the three PEST domain serines reside in a consensus CKII phosphorylation site. Furthermore, although we find that mutation of any single PEST domain serine does not eliminate CKII-mediated phosphorylation of Cactus (data not shown), Gay and colleagues have recently found that Ser-468 is the predominant site of modification in vitro (Packman et al. 1997). We expect, therefore, that CKII phosphorylation introduces less negative charge than three serine-to-glutamate substitutions.

Taken together, our results shows that generation of a fully functional Cactus PEST domain requires CKII-catalyzed phosphorylation. Furthermore, in light of the fact that PEST-mediated turnover of Cactus is essential for wild-type signal transduction (Belvin et al. 1995; Bergmann et al. 1996; Table 1), these results also indicate that CKII plays an essential role in wild-type patterning of the Drosophila embryo.

The role of PEST-mediated proteolysis in dorsoventral patterning

In the absence of Toll-mediated signaling, the steady-state level of Cactus in embryos is maintained by an equilibrium between synthesis and degradation of free Cactus. That injection of cactus antisense RNA phenocopies a loss of cactus function indicates that translation of Cactus is required to maintain Dorsal in the embryonic cytoplasm (Geisler et al. 1992). That free Cactus undergoes signal-independent degradation is evident from the phenotype of dorsal null mutants, which, although wild-type for the cactus locus, do not accumulate any Cactus protein. As a result of the synthesis and degradation of free Cactus, the level of Cactus in the embryo closely parallels that of Dorsal (Whalen and Steward 1993; Bergmann et al. 1996).

It is essential that the levels of Dorsal and Cactus be in balance. If there is too little Cactus, as in embryos derived from cactus mutant mothers, Dorsal translocates into dorsal as well as ventral nuclei (Roth et al. 1991). If there is too much Cactus, as in embryos expressing CactΔPEST, the shape of the gradient is also altered (Belvin et al. 1995). The mechanism that has evolved to achieve this balance is simple: Any Cactus protein not bound to Dorsal is degraded (Whalen and Steward 1993). This process is evidently quite efficient, because neither microinjection of large amounts of cactwt RNA nor a twofold alteration in the gene dosage of Cactus or Dorsal has adverse effects on embryonic development (Table 1; Govind et al. 1993).

The decrease in the slope of the Dorsal gradient seen on introduction of CactΔPEST into embryos indicates an inefficient degradation of Dorsal–Cactus or Dorsal–CactΔPEST complexes in these embryos. This may reflect an ability of free CactΔPEST to serve as a sink for the signaling machinery, as has been suggested previously (Belvin et al. 1995; Bergmann et al. 1996; Reach et al. 1996). Our results here suggest an additional explanation. When the ratio of Dorsal to wild-type or mutant Cactus in our in vitro binding experiments was comparable with that in embryos, Dorsal bound its inhibitor with a 2:1 stoichiometry. At higher concentrations of Cactus, however, we detected a complex containing one molecule each of Cactus and Dorsal, a configuration not found in wild-type embryos (Isoda and Nüsslein-Volhard 1994). If high concentrations of CactΔPEST also drive formation of Cact–Dl complexes in vivo, such complexes might differ in their response to Toll-mediated signaling and thereby disrupt signal transduction to Dorsal.

CKII phosphorylation may play a general role in PEST domain function

The carboxy-terminal PEST domain of the mammalian Cactus counterpart IκBα is also phosphorylated by CKII (Barroga et al. 1995). This modification is required for degradation of IκBα in an in vitro assay (McElhinny et al. 1996). Furthermore, mutations in the CKII sites alter IκBα stability in transfected cells (Lin et al. 1996; Schwarz et al. 1996). It is not known, however, whether phosphorylation of IκBα by CKII is required for wild-type signaling to NF-κB. In the case of IκBβ, CKII modification of the PEST domain alters its ability to bind and inhibit c-rel (Chu et al. 1996), unlike what we observe for Cactus and Dorsal.

Consideration of the sequence composition of PEST domains indicates that CKII might have a general role in PEST domain function. In their original presentation of the PEST hypothesis (Rogers et al. 1986), Rechsteiner and colleagues noted that many PEST sequences contain potential sites for phosphorylation by casein kinases. By their very definition, PEST domains contain serine and threonine residues in close proximity to acidic side chains, very frequently resulting in one or more consensus sites for phosphorylation by CKII.

Mann and colleagues have recently shown that CKII phosphorylates the Drosophila Antennapedia protein (Jaffe et al. 1997). They have mapped the two predominant sites of CKII phosphorylation and shown that mutations in these sites alter Antennapedia behavior in vivo. In light of our findings, we have searched the Antennapedia sequence for PEST domains and find a predicted PEST domain (residues 359–379) that contains one of the two sites of CKII phosphorylation (Ser-364). Therefore, it may be that Antennapedia, like Cactus, is subject to CKII- and PEST-mediated proteolysis. We note, however, that other Drosophila proteins, for example, Dishevelled, as well as many vertebrate transcription factors and signaling proteins, for example, c-Jun and protein phosphatase 2A, are phosphorylated by CKII yet lack recognizable PEST domains (Lin et al. 1992; Willert et al. 1997; Hériché et al. 1997).

PEST sequences are present in many classes of proteins, including metabolic enzymes, transcription factors, protein kinases, protein phosphatases, and cyclins. Given that PEST sequences are often conditional proteolytic signals (Rechsteiner and Rogers 1996) and that the sequence and activity of CKII have been highly conserved during evolution (Saxena et al. 1987), CKII might serve as a general regulator of PEST-mediated protein degradation.

A difficulty in proposing CKII as a regulator of PEST function is the lack of evidence for modulation of CKII specific activity in vivo (Meisner and Czech 1991). If CKII activity is constitutive, it could nevertheless be instrumental in regulation, provided a counterbalancing activity were modulated or access to the phosphorylation site were conditional. For example, the coupling of a basal level of CKII phosphorylation with a regulated phosphatase could provide the basis for controlling PEST function. Alternatively, a protein–protein interaction that occludes a PEST domain could regulate the level of CKII-mediated phosphorylation. Whether mechanisms such as these do regulate protein turnover remains an open question.

Materials and Methods

In-gel kinase assay

Oregon R was used as the wild-type stock; mutations and balancers are described in FlyBase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu). Embryonic extracts were prepared as described by Gillespie and Wasserman (1994). For the in-gel kinase assay (Hibi et al. 1993), total protein (20 μg) prepared from 0–3 hr embryos was subjected to electrophoresis in an 8% SDS–polyacrylamide gel that had been polymerized in the presence 40 μg of bacterially expressed Cactus (hexahistidine-tagged Cactus or GST–Cactus) per milliliter of gel. Following electrophoresis, the gel was washed twice for 30 min with 50 mm Tris at pH 8, in 20% isopropanol, twice for 30 min with buffer B (50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol), and once for 1 hr with 200 ml of buffer B containing 6 m guanidinium HCl. The proteins in the gel were then renatured overnight at 4°C in 200 ml of buffer B containing 0.05% Tween 20. Next, the gel was incubated in kinase buffer (25 mm HEPES at pH 7.9, 10 mm MgCl2, 2 mm MnCl2, 25 μm ATP) containing 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP per ml at room temperature for 1 hr. This incubation was followed by five washes of 200 ml each with 5% trichloroacetic acid, 1% sodium pyrophosphate at room temperature. The gel was then dried and subjected to autoradiography.

Purification of the Cactus kinase

Protamine sulfate (∼0.1 gram of protamine sulfate/3 gram of protein) was added gradually to the clarified embryonic extract at 4°C. Following an additional 15 min stirring, the solution was subjected to centrifugation at 39,000g for 20 min. The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of buffer A (10 mm imidazole at pH 6.5) containing 2 m NaCl, 0.5 mg of DNase I, and 10 mm MgCl2. After incubation at room temperature for 1 hr, the solution was dialyzed for 4 hr at 4°C against 1 liter of buffer A containing 2 m NaCl, and then overnight against 2 liters of buffer A containing 0.5 m NaCl. After removal of insoluble material by centrifugation, the solution was diluted fivefold with buffer A.

Fifty milliliters of clarified and diluted dialysate was loaded onto a Mono Q 5/5 column (Pharmacia) equilibrated previously with buffer A. Bound proteins were eluted with a gradient of 0–1 m NaCl in Buffer A. Fractions containing the CKII activity were pooled and applied to a phenyl–Sepharose HP column (Pharmacia) after addition of ammonium sulfate solution to a final concentration of 0.3 m. The phenyl–Sepharose column was then washed with buffer A containing 0.3 m ammonium sulfate, and protein was eluted with a descending gradient of 0.3–0 m ammonium sulfate in buffer A. Fractions containing kinase activity were collected and pooled.

In vitro kinase assay and phosphoamino acid analysis

GST-Cactus was incubated with purified CKII in 30 μl of kinase buffer containing 150 mm NaCl and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP at 30°C for 15 min. The kinase reaction was stopped by the addition of 10 μl of 5× SDS sample buffer and boiling for 3 min. Phosphoproteins were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide followed by autoradiography of dried gels. Phosphoamino acid analysis was performed as described previously (Boyle et al. 1991).

Immunoprecipitation

Frozen, dechorionated 0- to 3-hr embryos were thawed on ice and lysed with a Dounce homogenizer in five volumes of TSA buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8, 140 mm NaCl, 0.025% sodium azide) containing 1% Triton X-100, 1% bovine hemoglobin, 5 mm iodoacetamide, 1 μm each of aprotinin, pepstatin, and leupeptin, and 1 mm PMSF. After incubation on ice for 1 hr, the lysate was centrifuged at 13,000g for 30 min. Five hundred microliters of supernatant was then incubated overnight with 15 μg of the IgG fraction from a polyclonal anti-Dorsal antisera. We used an anti-Dorsal serum in this procedure, because this serum is particularly effective in immunoprecipitating Cactus, all, or nearly all, of which is bound to Dorsal in vivo (Bergmann et al. 1996; Z.-P. Liu, unpubl.). The antibody–protein complexes were recovered on protein A–Sepharose beads (Sigma).

In vitro dephosphorylation and phosphorylation assay

Immunoprecipitates collected on protein A–Sepharose were washed twice with 1 ml of RIPA buffer, twice with 1 ml of TSA buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% bovine hemoglobin, once with 1 ml of TSA buffer, and once with 0.5 ml of CIP buffer (NEB). The dephosphorylation reaction was carried out in 50 μl of CIP buffer at 37°C for 1 hr with 10 units of CIP (NEB). For the phosphorylation reaction, the immunoprecipitates were further washed with 0.5 ml of kinase buffer and incubated with purified CKII in kinase buffer for 30 min at 30°C. The complexes were separated on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore), then subjected to autoradiography and immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblot analysis was carried out as described previously (Gillespie and Wasserman 1994), by use of anti-Cactus antibodies directly conjugated to alkaline-phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim). The antibody-antigen complexes were visualized by a chemiluminescence detection system (Tropix). HA-Cact isoforms were detected with a 1/1000 dilution of High Affinity Monoclonal Anti-HA Antibody (Boehringer Mannheim). Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rat immunoglobulin G (Tropix), was used at a dilution of 1/10,000. To control for loading, the PVDF membrane was reprobed with a 1/5000 dilution of streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Tago, Inc.). Image analysis was performed with Adobe Photoshop to normalize loading.

Construct formation

The wild-type cactus, cactΔPEST, cactnSA4 (formerly cactSA4), and cactnSA4,ΔPEST constructs have been described previously (Reach et al. 1996). Site-directed mutagenesis of the wild-type cactus cDNA was used to generate the cactcSA1, cactcSA3, and cactcSE3 mutations. To generate the HA-tagged constructs, two copies of the HA epitope were introduced onto the amino terminus of Cactus by two rounds of PCR amplification.

Protein expression and purification

The Hexahistidine-tagged (His6) Cactus and GST-tagged Cactus was prepared by growing BL21(DE3) bacteria at 37°C to an A600 of 0.8 and inducing with Isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 0.1 mm. After an additional 4 hr incubation, bacteria were harvested, resuspended in 1/200 volume of PBS, and stored at −80°C. His6–Cactus and GST–Cactus were purified on Ni+–NTA and glutathione–agarose columns, respectively.

RNA synthesis, embryo injection, and cuticle preparations

RNA synthesis and cuticle preparation were performed as described previously (Galindo et al. 1995), except that RNA was purified by RNeasy (Qiagen) spin column chromatography. Cuticles were scored for the phenotype exhibited by the region surrounding the posterior site of RNA injection. For immunoblot analysis after RNA microinjection, embryonic contents were collected as described previously (Reach et al 1996).

Protein binding and gel shift assay

Interaction assays for proteins translated in vitro (Promega) contained 0.5 μl of unlabeled Dorsal (∼10 fmoles) and varying amounts (4–60 fmoles) of 35S-labeled Cactus, either wild-type or mutant. Transcription-translations were performed according to manufacturer’s protocols with the reticulocyte TNT SP6-coupled system from Promega. Each binding reaction was carried out in TSA buffer in a final volume of 13.5 μl and was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The reaction mixture was then loaded onto a 5% native polyacrylamide gel (37.5:1 acrylamide/bis ratio) and subjected to electrophoresis in pH 9.4 buffer (60 mm Tris, 40 mm CAPS) at 4°C at 215 V for 90 min. The gel was then dried and subjected to autoradiography.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carolyn Moomaw and Clive Slaughter for the amino-terminal sequencing of CKII and Alisha Tizenor for assistance in figure preparation. These studies were supported by grant RO1 GM50545 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (to S.A.W.) and by stipend support provided by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (to Z.-P.L.) and by an NIH training grant (to R.L.G.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL Stevenw@hamon.swmed.edu; FAX (214) 648-1196.

References

- Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. NF-κB: Ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroga CF, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Verma IM. Constitutive phosphorylation of IκBα by casein kinase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:7637–7641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvin MP, Jin Y, Anderson KV. Cactus protein degradation mediates Drosophila dorsal-ventral signaling. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:783–793. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann A, Stein D, Geisler R, Hagenmaier S, Schmid B, Fernandez N, Schnell B, Nüsslein-Volhard C. A gradient of cytoplasmic Cactus degradation establishes the nuclear localization gradient of the dorsal morphogen in Drosophila. Mech Dev. 1996;60:109–123. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00607-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle WJ, van der Geer P, Hunter T. Phosphopeptide mapping and phosphoamino acid analysis by two-dimensional separation on thin-layer cellulose plates. Methods Enzymol. 1991;201:110–149. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01013-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Gerstberger S, Carlson L, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. Control of IκBα proteolysis by site-specific, signal-induced phosphorylation. Science. 1995;267:1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.7878466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Henzel WJ, Gao X. IRAK: A kinase associated with the interleukin-1 receptor. Science. 1996;271:1128–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasan R, Anderson KV. Maternal control of dorsal-ventral polarity and pattern in the embryo. In: Bate M, Martinez-Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 387–432. [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z-L, McKinsey TA, Liu L, Qi X, Ballard DW. Basal phosphorylation of the PEST domain in IκBβ regulates its functional interaction with the c-rel proto-oncogene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5974–5984. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo RL, Edwards DN, Gillespie SKH, Wasserman SA. Interaction of the pelle kinase with the membrane-associated protein tube is required for transduction of the dorsoventral signal in Drosophila embryos. Development. 1995;121:2209–2218. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.7.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler R, Bergmann A, Hiromi Y, Nüsslein-Volhard C. cactus, a gene involved in dorsoventral pattern formation of Drosophila, is related to the IκB gene family of vertebrates. Cell. 1992;71:613–621. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie SK, Wasserman SA. Dorsal, a Drosophila Rel-like protein, is phosphorylated upon activation of the transmembrane protein Toll. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3559–3568. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover CV, Shelton ER, Brutlag DL. Purification and characterization of a type II casein kinase from Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:3258–3265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govind S, Brennan L, Steward R. Homeostatic balance between dorsal and cactus proteins in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 1993;117:135–148. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hériché J-K, Lebrin F, Rabilloud T, Leroy D, Chambaz EM, Goldberg Y. Regulation of protein phosphatase 2A by direct interaction with casein kinase 2α. Science. 1997;276:952–995. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5314.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibi M, Lin A, Smeal T, Minden A, Karin M. Identification of an oncoprotein- and UV-responsive protein kinase that binds and potentiates the c-Jun activation domain. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:2135–2148. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isoda K, Nüsslein-Volhard C. Disulfide cross-linking in crude embryonic lysates reveals three complexes of the Drosophila morphogen dorsal and its inhibitor cactus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:5350–5354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe L, Ryoo H-D, Mann RS. A role for phosphorylation by casein kinase II in modulating Antennapedia activity in Drosophila. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:1327–1340. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.10.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd S. Characterization of the Drosophila cactus locus and analysis of interactions between cactus and dorsal proteins. Cell. 1992;71:623–635. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90596-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Frost J, Deng T, Smeal T, al-Alawi N, Kikkawa U, Hunter T, Brenner D, Karin M. Casein kinase II is a negative regulator of c-Jun DNA binding and AP-1 activity. Cell. 1992;70:777–789. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90311-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Beauparlant P, Makris C, Meloche S, Hiscott J. Phosphorylation of IκBα in the C-terminal PEST domain by casein kinase II affects intrinsic protein stability. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1401–1409. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhinny JA, Trushin SA, Bren GD, Chester N, Paya CV. Casein kinase II phosphorylates IκBα at S-283, S-289, S-293, and T-291 and is required for its degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:899–906. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisner H, Czech MP. Phosphorylation of transcriptional factors and cell-cycle-dependent proteins by casein kinase II. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1991;3:474–483. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(91)90076-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packman LC, Kubota K, Parker J, Gay NJ. Casein kinase II phosphorylates Ser468 in the PEST domain of the Drosophila IκB homologue cactus. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palombella VJ, Rando OJ, Goldberg AL, Maniatis T. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is required for processing the NF-κB1 precursor protein and the activation of NF-κB. Cell. 1994;78:773–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna LA. Casein kinase 2: An “eminence grise” in cellular regulation? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1054:267–284. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(90)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reach M, Galindo RL, Towb P, Allen JL, Karin M, Wasserman SA. A gradient of cactus protein degradation establishes dorsoventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Dev Biol. 1996;180:353–364. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechsteiner M, Rogers SW. PEST sequences and regulation by proteolysis. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SW, Wells R, Rechsteiner M. Amino acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: The PEST hypothesis. Science. 1986;234:364–368. doi: 10.1126/science.2876518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Hiromi Y, Godt D, Nüsslein-Volhard C. cactus, a maternal gene required for proper formation of the dorsoventral morphogen gradient in Drosophila embryos. Development. 1991;112:371–388. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena A, Padmanabha R, Glover CV. Isolation and sequencing of cDNA clones encoding α and β subunits of Drosophila melanogaster casein kinase II. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:3409–3417. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.10.3409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz EM, van Antwerp D, Verma IM. Constitutive phosphorylation of IκBα by casein kinase II occurs preferentially at serine 293: Requirement for degradation of free IκBα. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;16:3554–3559. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton CA, Wasserman SA. pelle encodes a protein kinase required to establish dorsoventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1993;72:515–525. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90071-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward R. Dorsal, an embryonic polarity gene in Drosophila, is homologous to the vertebrate proto-oncogene, c-rel. Science. 1987;238:692–694. doi: 10.1126/science.3118464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traenckner EB, Pahl HL, Henkel T, Schmidt KN, Wilk S, Baeuerle PA. Phosphorylation of human IκBα on serines 32 and 36 controls IκBα proteolysis and NF-κB activation in response to diverse stimuli. EMBO J. 1995;14:2876–2883. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Antwerp DJ, Verma IM. Signal-induced degradation of IκBα: Association with NF-κB and the PEST sequence in IκBα are not required. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6037–6045. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF-κB/IκB family: Intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman SA. A conserved signal transduction pathway regulating the activity of the rel-like proteins dorsal and NF-κB. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:767–771. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.8.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalen AM, Steward R. Dissociation of the dorsal-cactus complex and phosphorylation of the dorsal protein correlate with the nuclear localization of dorsal. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:523–534. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.3.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K, Brink M, Wodarz A, Varmus H, Nusse R. Casein kinase 2 associates with and phosphorylates Dishevelled. EMBO J. 1997;16:3089–3097. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]