Abstract

Plagiarism and inadequate citing appear to have reached epidemic proportions in research publication. This article discusses how plagiarism is defined and suggests some possible causes for the increase in the plagiarism disease. Most editors do not have much tolerance for text re-use with inadequate citation regardless of reasons why words are copied from other sources without correct attribution. However, there is now some awareness that re-use of words in research articles to improve the writing or “the English” (which has become a common practice) should be distinguished from intentional deceit for the purpose of stealing other authors’ ideas (which appears to remain a very rare practice). Although it has become almost as easy for editors to detect duplicate text as it is for authors to re-use text from other sources, editors often fail to consider the reasons why researchers resort to this strategy, and tend to consider any text duplication as a symptom of serious misconduct. As a result, some authors may be stigmatized unfairly by being labeled as plagiarists. The article concludes with practical advice for researchers on how to improve their writing and citing skills and thus avoid accusations of plagiarism.

Keywords: Plagiarism, editors, authors

INTRODUCTION

“Plagiarism” (also called “plagiary”) in research publication means an unethical act that is done to deceive readers about the origin of the ideas or words. It is usually considered a conscious, voluntary act that is done intentionally to copy something, and to mislead the reader into believing wrongly that the person whose name appears as the author was the original intellectual source of words or ideas that were in fact taken from another source.

Two kinds of plagiarism are recognized: plagiarism of data (or ideas) and plagiarism of text (or words).[8,17,19] If editors and reviewers discover plagiarism, even if it involves only words and not data or ideas, they may suspect the authors of being dishonest about the scientific data and may even suspect research fraud.[13]

PLAGIARISM, GOOD CITATION PRACTICE AND GOOD SCIENTIFIC ENGLISH STYLE

Plagiarism due to inaccurate citation may be unintentional if the authors are unfamiliar with the journal's requirements or intentional if the purpose is to deceive or mislead readers. Researchers in countries where English is not the first language may believe that language re-use (to improve “the English” and avoid rejection because of language or writing faults) is not plagiarism. However, many editors consider authors guilty of plagiarism even if references and quotation marks are missing as a result of copy-and-paste writing to improve the English, and not caused by the intention to steal another scientist's ideas.

Correct citation and accurate referencing of the sources are effective ways to prevent unintentional plagiarism. Accurate citing and referencing are the responsibility of all coauthors. Even if only one of the coauthors copied any part of the text or did not include all the necessary references, the editor may consider all coauthors equally responsible in accordance with the authorship criteria stipulated by the ICMJE.[10] So, the undesirable consequences of inaccurate citation and referencing can affect the reputation and career of all the coauthors. These consequences can also be harmful for the reputation of their department, their university or other institution, or even their country, especially if an article is retracted, and influential international journals or well-known internet sources publish news about the retraction.

Journal editors in western countries usually do not have much sympathy for authors’ problems with the English language. To make things even worse for authors, the feedback about “the English” from some reviewers may not be helpful or even correct.[15] However, many editors consider copy-and-paste writing (also called patch writing and language re-use) as a kind of plagiarism, even if the purpose is to produce good English and even if the correct references are given. If the same words are used, they must be in quotation marks (“like this”) and the reference must be given. Regardless of whether the words are repeated verbatim or paraphrased, the reference must be given. Even paraphrased words are considered plagiarism if the idea is not the author's original idea and the reference to the source of the original idea is not cited.

The Committee on Publication Ethics considers that plagiarism can be proven even in two different languages.[3] Translation plagiarism occurs when a translation is published without a reference to the original publication in the original language. Nonetheless, secondary publication in another language is considered an acceptable way to make information available to readers who do not have access to the information in the first language. Permission to publish the same article in another language must be obtained from the copyright holders (the journal, the publisher or the authors), and the publisher of the second language version must be informed that the text is a translation of an earlier publication.[2,11]

EDITORS AND PLAGIARISM

Editors, reviewers and other readers need to know which findings, ideas and words are original and which ones are taken from other sources. It is good ethical and scientific practice to acknowledge intellectual debts for ideas and information from any source, including non-academic sources and non–peer-reviewed sources (e.g., blogs and websites). Giving due credit and acknowledging priority for new findings and ideas are practices that are valued highly by the international research community.

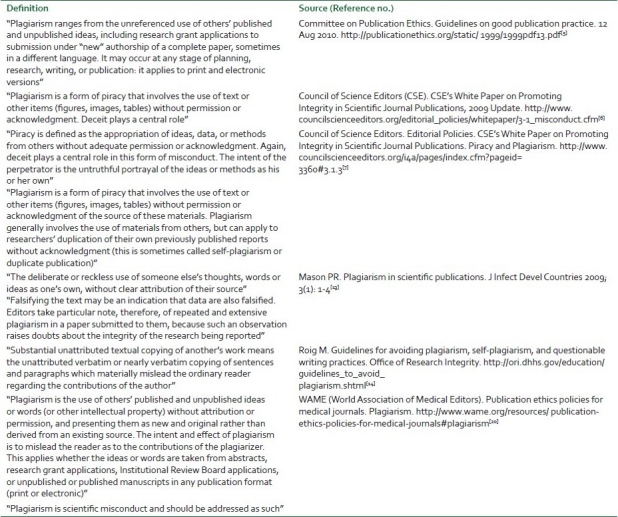

Beyond these universally accepted values in scientific culture, however, experts in research publication ethics do not agree entirely on the definition of plagiarism. If an editor discovers copied text in a manuscript, his or her reaction will depend on which definition the editor prefers [Table 1]. Most current definitions emphasize the lack of accurate attribution to the original source as the main sign of plagiarism, but not all definitions specify the intention to deceive readers (i.e., the premeditated omission of references to known earlier sources with the intention of falsifying the scientific record of originality) as a criterion. According to most current definitions, any incorrectly cited or misattributed material is considered plagiarism regardless of the reasons why copied material has been used. As a result, in many cases, unintentional plagiarism (due to lack of skills in writing or citing) is considered as serious a violation of good research ethics as plagiarism done intentionally to deceive readers about the authorship of the information. It is only recently that the relative severity of the “disease” has been questioned according to whether the main “symptom” is re-use of words only or the misattribution of ideas.[1,9,17]

Table 1.

Current definitions of plagiarism by different authorities in research publication ethics, with emphasis added for language regarding cause (the intent to mislead or deceive readers) or the symptom (inaccurate citation)

Many editors now check all manuscripts to try to identify plagiarism and inaccurate citation before publication. Software tools such as iThenticate and CrossCheck have been developed for editors and publishers to check for plagiarism. These tools find matches between two or more texts and locate places where the same text has been used, but they cannot judge the guilt or innocence of the writer who re-used the text. The software is not intelligent and cannot interpret the reasons for the duplication – it simply identifies strings of identical digital code for letters and numbers. This means that the software cannot decide if matching texts represent intentional plagiarism, an honest mistake, or the availability of the same text from two or more different sources for legitimate reasons.

Editors have different policies on how to handle manuscripts with duplicated text. Although each case of duplicate text should be considered individually, some editors with little time for this task assume that if the software finds a match, it must be plagiarism. Some editors simply reject the manuscript, even if the duplicated text involves only a few lines. Editors fortunate enough to have sufficient time and resources may try to determine whether there are signs that the authors are attempting to mislead readers about the source of the original information[4,16] or were simply repeating well-known methods or widely accepted ideas.

Unfortunately, many editors do not have the time to analyze why the software has found duplicate texts. They may consider a few lines of identical or very similar text as evidence that the authors have tried to deceive the readers about the origin of the text, without considering alternative hypotheses to account for the duplication:

The material may be available on more than one website (e.g., abstracting services and databases) for legitimate reasons.

The authors may wish to improve the use of English to avoid rejection of their manuscript.[9,12]

The information may be of a highly technical nature and there may be limited ways to communicate it correctly and accurately in English.

The authors may not have received guidance in correct citation practices and may make mistakes due to ignorance rather than an intent to deceive the readers.

The authors may be under extreme pressure to publish because of the competitive nature of research evaluation and funding decisions. This may lead them to use copy-and-paste writing to increase their publication output.

The authors may have re-used the exact words of the original authors because the latter published a very novel or unusual idea that is best communicated in the original authors’ original words, in order to express the idea in the clearest way possible for new readers.

Stealing an original idea or original data is not a very common behavior, since outright intellectual theft is easy for peers to detect. The dissuasive power of the community of potential whistleblowers (peer reviewers and readers) operates to stop most researchers from attempting this obviously unethical tactic. I believe that most of the current problems with the plagiarism disease are related to missing or inaccurate citations and the difficulties of writing in English, rather than to a malicious intent to deceive the readers about the originality of the text. As suggested by Steen,[17] the use of retraction to correct the literature after plagiarized material has been published may be an unnecessarily punitive step for editors to take if the authors re-used part of a text to improve the language but with no intent to steal intellectual credit for the content.

Moreover, whether readers feel they have been “deceived” about the original source of the information may depend on reader-dependent factors such as attentiveness, familiarity with the research area, knowledge of previous publications, and the importance the reader attaches to the information. Readers may be more sensitive to inaccurate or misleading citation if the information communicates a fundamental new insight representing a significant advance in the field. In contrast, readers may be less sensitive to plagiarism if the text reports technical details, background information or well-known assumptions that are widely accepted.

In research publication (unlike fiction, poetry and other types of creative literature), clear communication is more important than eloquence or style.[9] Decisions to reject a manuscript because parts of the text matched parts of earlier publications may be an efficient way to reduce the editorial office's workload. But if the editor does not justify the decision by explaining that parts of the manuscript needed to be referenced to an earlier source or needed to be paraphrased, the authors may not realize the nature of the problem and may simply submit their manuscript to another journal, which may accept and publish the paper without detecting the duplicated text. On the other hand, if editors do not consider the reasons why parts of the text in a submitted manuscript duplicate parts of earlier publications, they may be rejecting good manuscripts for reasons related more to expediency and convenience than to protecting the integrity of the literature. “When in doubt, reject” has practical advantages, but do these advantages outweigh the risk of delaying or preventing the publication of useful research?

HOW CAN RESEARCHERS IMPROVE CITATION ACCURACY AND AVOID ACCUSATIONS OF PLAGIARISM?

Citation and referencing errors cause a negative impression on editors, reviewers and readers. Inaccurate or missing citations of the original sources can lead to an accusation of plagiarism. Errors in citations can bias reviewers and editors against a manuscript and lead them to reject it. In specialized and developing areas of research, the number of experts is small, so the reviewer of a manuscript may be one of the authors of an article that is not correctly cited. Reviewers who discover they have been plagiarized or misquoted are not likely to recommend acceptance of the manuscript.

Even if the peer reviewers or editor do not discover the citation errors or plagiarism, readers who are experts in the research area will probably discover them after the article is published. They may submit a letter to the editor or report their discovery to the editor or publisher in some other (possibly less collegial) way. Here are some suggestions to help honest researchers avoid unfair and potentially damaging accusations of plagiarism.

Avoid copy-and-paste writing. The English may not be very good in the article you use as the source. Many articles in an unreadable writing style are published even in top journals.[18]

Insert provisional references (author and year of publication) in the first drafts of your manuscript for every idea, direct quotation or paraphrased material taken from an earlier source. Convert them to the correct format according to the journal's requirements after the manuscript is completely finished.

Always use quotation marks (“ ”) to indicate verbatim quotations (even if they are only a few words) if they communicate an original finding, concept or interpretation by other authors, and provide the reference. This applies equally to text re-used from your own earlier publications and from the publications of other researchers. However, for well-known methods that need to be described accurately, it may not be necessary to use quotation marks although the correct references for each method must still be provided.

If you are the guarantor, corresponding author or first author, revise all the text yourself or make sure that all coauthors have used quotation marks, paraphrasing and citations correctly.

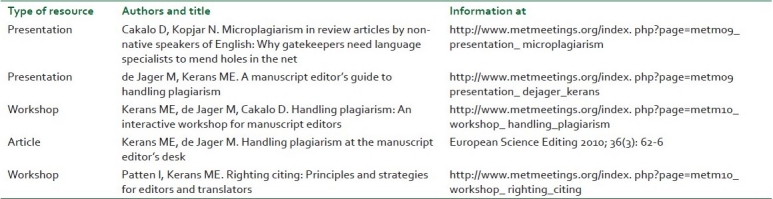

Ask a more experienced colleague or an author's editor for advice. Your institution may have a writing center or research development center where you can ask for help [Table 2].

Check your manuscript before you submit it to the journal for phrases, sentences and paragraphs that have been published previously. If the language in part of the manuscript changes abruptly to a grammatically more complex style or if all language errors suddenly disappear, it is a good idea to paste that part of the text into a web browser search window and press the Enter key to launch an internet search. Exact matches for consecutive strings of words are evidence (but not proof) that the text has been copied. A negative search result (i.e., no matches) is not enough to rule out copying, since the text may be taken from a book, a report, or some other document not available on the internet.

Always tell the editor, when you first submit a manuscript, which parts of it have been copied from your own earlier publications. Always include correct citations to your earlier publications. This can avoid the impression of “self-plagiarism”.

Table 2.

Brief description of some of the resources of Mediterranean Editors and Translators, a not-for-profit association based in Barcelona, Spain, offering training for author's editors, journal editors, copyeditors and researchers in good research writing and citation practices

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the Vice-Chancellery for Research of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and the Deputy Minister for Research and Technology at the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education for moral and financial support for the Author AID in the Eastern Mediterranean project, which made it possible for me to write this article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous Seminar attendees ponder plagiarism.Cultural differences in plagiarism. Ethical Editing. 2010;2:5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous [Table 1]. Generally permissible and nonpermissible forms of duplicate/overlapping publication. Guidance on duplicate publication for BioMed Central Journal Editors. [Last accessed on 2010]. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/about/duplicatepublication .

- 3.Committee on Publication Ethics. Definition of plagiarism? Case number: 07-05. [Last accessed on 2011 March 24]. Available from: http://publicationethics.org/case/definition-plagiarism .

- 4.Committee on Publication Ethics. Flowcharts. [Last accessed on 2011 March 24]. Available from: http://publicationethics.org/flowcharts .

- 5.Committee on Publication Ethics. Guidelines on good publication practice. [Last accessed on 2011 March 24]. Available from: http://publicationethics.org/static/1999/1999pdf13.pdf .

- 6.Council of Science Editors. CSE's White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications, 2009 Update. [Last accessed on 2009]. Available from: http://www.councilscienceeditors.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3313 .

- 7.Council of Science Editors. Editorial Policies. CSE's White Paper on Promiting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications. Piracy and Plagiarism. [Last accessed on 2011 March 24]. Available from: http://www.councilscienceeditors.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3360#3.1.3 .

- 8.Habibzadeh F. On stealing words and ideas. Hepatitis Monthly. 2008;8:171–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habibzadeh F, Shashok K. Plagiarism in scientific writing: words or ideas? Croatian Med J. 2011;52 doi: 10.3325/cmj.2011.52.576. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: Ethical Considerations in the Conduct and Reporting of Research: Authorship and Contributorship. [Last accessed on 2011 March 24]. Available from: http://www.icmje.org/ethical_1author.html .

- 11.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals: Publishing and Editorial Issues Related to Publication in Biomedical Journals: Overlapping Publications: Acceptable Secondary Publication. [Last accessed on 2011 March 24]. Available from: http://www.icmje.org/publishing_4overlap.html .

- 12.Kleinert S. on behalf of the editors of all Lancet journals.Checking for plagiarism, duplicate publication, and text recycling. Lancet. 2010;377:281–2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason PR. Plagiarism in scientific publications. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:1–4. doi: 10.3855/jidc.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roig M. Guidelines for avoiding plagiarism, self-plagiarism, and questionable writing practices. Office of Research Integrity. [Last accessed on 2011 March 24]. Available from: http://ori.dhhs.gov/education/guidelines_to_avoid_plagiarism.shtml .

- 15.Shashok K. Content and communication: How can peer review provide helpful feedback about the writing? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shashok K. Crossing the thin line between paraphrasing without citation and plagiarism: the Sticklen retraction. Write Stuff. 2010;19:122–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steen RG. Retractions in the scientific literature: Do authors deliberately commit research fraud? J Med Ethics. 2011;37:113–7. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.038125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasconcelos SM. Writing up research in English: Choice or necessity? Rev Col Bras Cir. 2007;34:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vessal K, Habibzadeh F. Rules of the game of scientific writing: fair play and plagiarism. Lancet. 2007;369:641. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Association of Medical Editors. Plagiarism. In: Publication ethics policies for medical journals. [Last accessed on 2011 March 24]. Available from: http://www.wame.org/resources/publication-ethicspolicies-for-medical-journals#plagiarism .