Abstract

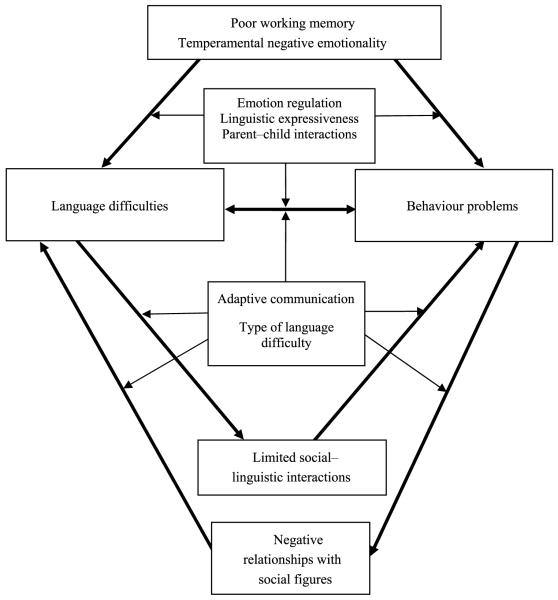

Three hypotheses have been posited as competing explanations for the comorbidity or co-occurrence of language difficulties and behavioural problems among children: (1) language difficulties confer risk for behaviour problems, (2) behaviour problems confer risk for language difficulties, and (3) shared risk factors account for their co-occurrence. We use a developmental psychopathology perspective to propose a model that integrates these explanations, and incorporates several potential moderating, mediating, and shared risk factors. We propose that temperamental negative emotionality and working memory deficits operate to initiate the pathway that may culminate in comorbid language and behaviour problems. We hypothesise that contextual factors (e.g. parent–child interactional processes) and child-specific factors (e.g. adaptive communication) may exacerbate or offset this risk and thus contribute to multiple developmental pathways. The proposed model underscores the importance of considering transactional processes from multiple domains to understand how configurations of risk and protective factors translate into different patterns of children’s linguistic and behavioural functioning.

Keywords: comorbidity, language difficulties, behaviour problems, developmental psychopathology, early childhood

The co-occurrence of behaviour problems and disordered or delayed language among children has been well documented in literatures spanning the fields of child psychology, psychiatry, education, and speech-language pathology (Gallagher, 1999). Elevated rates of disruptive behaviour problems have been reported among children with language delay or disorders (Horowitz, Westlund, & Ljungberg, 2007; van Daal, Verhoeven, & van Balkom, 2007; Willinger et al., 2003), as well as high rates of linguistic difficulties among children who meet diagnostic criteria for psychological disorders (Cohen et al., 1998; Ripley & Yuil, 2005). For example, a review of 26 studies revealed that 71% of children with emotional/behavioural problems experienced clinically significant language difficulties, and 57% of children with language difficulties also evidenced clinically significant emotional/behavioural problems (Benner, Nelson, & Epstein, 2002).

Considered separately, clinically significant behaviour problems are estimated to affect 10% to 15% of preschool children (Campbell, 1995). Other estimates suggest that nearly 17% of preschool children meet criteria for oppositional defiant disorder and that 20% experience moderate levels of externalising symptoms (Lavigne et al., 1996; Pianta & Caldwell, 1990). Although some children evidence decreases in externalising behaviours over time, nearly 20% of children with initially moderate or high levels of aggressive behaviour follow a fairly stable course over time, with negative outcomes (e.g. social maladjustment, academic problems) apparent at 12 years of age (Campbell, Spieker, Burchinal, & Poe, 2006). Externalising behaviour problems are associated with additional maladaptive correlates, including peer rejection, social skill deficits, academic difficulties, and high rates of expulsion and suspension from preschool and day care (Gilliam & Shahar, 2006; Qi & Kaiser, 2003).

Estimates of language delay range from 12.5% to 15% among older infants and toddlers, and 18% to 28% among 30–39-month-olds (Horwitz et al., 2003). Children with early language difficulties experience long-term adverse outcomes, including demoralisation, higher levels of grade retention, and lowered academic performance, even subsequent to the resolution of their language problems (Benner et al., 2002; Catts, 1993; Harrison, McLeod, Berthelsen, & Walker, 2009; Snowling, Bishop, Stothard, Chipchase, & Kaplan, 2006). Given that both language difficulties and externalising behaviours are associated with negative correlates and sequelae, examining processes that may underlie co-occurring linguistic and behavioural difficulties could inform aetiological and intervention models at a time when these processes are amenable to intervention, and prior to the development of additional sequelae.

Despite the well-documented comorbidity between linguistic and behavioural difficulties, the potential mechanisms underlying this relation are not well understood. At least three explanations have been proposed for their co-occurrence (Dionne, Tremblay, Boivin, Laplante, & Perusse, 2003; Schoenfeld, Shaffer, O’Connor, & Portnoy, 1988; Willinger et al., 2003). First, language difficulties may confer risk for behaviour problems. For example, children may react with frustration and engage in problematic behaviours when they are unable to communicate effectively with others. In support of this explanation, two studies have reported that lower levels of early language skills temporally preceded the development of behavioural problems (Brownlie et al., 2004; Fagan & Iglesias, 2000).

Second, behaviour problems may interfere with the development and acquisition of developmentally relevant language abilities and thus contribute to language difficulties. Third, the association between behaviour problems and language difficulties may stem from shared aetiologies or risk processes (Gilliam & de Mesquita, 2000). These three potential explanations often are discussed as mutually exclusive, competing explanations (e.g. Pine et al., 1997). However, given the heterogeneity of the population of children with comorbid linguistic and behavioural difficulties, it is unlikely that there is a single explanation for the causal mechanisms underlying this comorbidity (Stevenson, 1996). Rather than ascertaining which explanation is most valid, the goal of future research endeavours could be to ascertain which explanation(s) hold true among which children. A developmental psychopathology perspective provides one potential framework to facilitate this goal.

A developmental psychopathology perspective on comorbidity

A developmental psychopathology perspective can be used as a unifying framework from which to examine questions concerning the development of complex clinical phenomena (Cicchetti & Toth, 2009; Drabick, 2009; Rutter & Sroufe, 2000), and often includes consideration of typical and atypical development, underlying developmental processes, and transactional relations across multiple domains of risk and protective factors. Given that the associations between language difficulties and behaviour problems likely differ based on a number of factors (e.g. type of language difficulties, developmental period, timing of language and behaviour problems, and moderating variables at the individual and contextual levels), consideration of these developmental psychopathology principles may illuminate the nature of the interrelations between language difficulties and behaviour problems.

In this theoretical paper, we propose an integrative, conceptual model intended to provide a more comprehensive account of the development of co-occurring linguistic and behavioural difficulties in early childhood. Thus, this paper is not intended to be an exhaustive review of the literature. We have limited the scope of the model to children without developmental disabilities or significant deficits in general cognitive ability. It is possible that developmental processes underlying the development of comorbidity may vary by sex, especially given: (1) higher rates of behaviour problems and language difficulties among boys (Campbell, 2002; Horwitz et al., 2003), and (2) sex differences in interrelations among risk factors for behaviour problems (Blatt-Eisengart, Drabick, Monahan, & Steinberg, 2009). The empirical literature has not provided sufficient evidence to inform separate models for boys and girls; we speculate that our proposed model may be more relevant for boys than girls during early childhood, although this is ultimately an empirical question.

We draw on several broad principles from the developmental psychopathology perspective in this paper: (1) the juxtaposition of typical and atypical development, (2) risk and protective factors drawn from multiple domains, and (3) equifinality and multifinality. We discuss interrelations between receptive and expressive language delays and externalising behaviours (i.e. non-compliant, aggressive, oppositional behaviours) across early childhood, and evaluate selected candidate processes from multiple domains to illustrate their potential relevance for a conceptual model. Next, we present an integrative model of behavioural and linguistic comorbidity to provide a multilevel, social–ecological framework from which to approach the study of cooccurring linguistic and behavioural difficulties. Last, we present implications and future directions for applying this model.

Juxtaposition of typical and atypical development

Examination of typical and atypical development and stage-specific processes is necessary for informing developmental models of language and behavioural processes and for identifying processes associated with risk and resilience. The co-occurrence of language and behaviour problems has been reported across the childhood years, including among older toddlers (e.g. Tervo, 2007), preschool children (e.g. McCabe, 2005), and kindergarteners/early school-aged children (Bowman, Barnett, Johnson, & Reeve, 2006). However, given differences in stage-salient linguistic and social developmental tasks, the magnitude and nature of linguistic and behavioural comorbidity vary from children’s first few years (birth to age three) to the preschool years (ages three to five).

Birth to three years

Within the first year of life, infants acquire the phonology of the native language and demonstrate the ability to discriminate word forms from speech, differentiate words with different patterns of lexical stress, and distinguish consonant sounds of the native language (e.g. bin vs. pin; for a review, see Gervain & Mehler, 2010). In general, children’s receptive language development precedes their expressive language development (Menyuk, Liebergott, & Schultz, 1995). Word comprehension first emerges in the middle of the first year, with children saying their first word around 12 months of age. Multiple cues underlie and facilitate word-learning, including the interaction of attentional, social, and linguistic cues (Hollich et al., 2000). Toddlers generally can understand and follow simple directions, although younger toddlers learn words relatively slowly and laboriously (Bloom, 1998). However, by the time children have amassed a vocabulary of 50 words, usually between 18 and 24 months, children experience a spurt of word-learning (‘the vocabulary spurt’), facilitated by better memory, pronunciation skills, and imitation (Gershkoff-Stowe & Smith, 2004; Tamis-LeMonda, Cristofaro, Rodriguez, & Bornstein, 2006; Woodward, Markman, & Fitzsimmons, 1994). After the vocabulary spurt, children begin combining two words, usually between 18 months and 30 months. Between 30 months and 36 months of age, children have begun to master grammar, often using adjectives, articles, and prepositional phrases correctly (Berk, 2002; Fernald, Thorpe, & Marchman, 2010; Valian, 1986).

The development of pretend play is another stage-salient task among typically developing older infants and toddlers. The development of language and pretend play is inherently intertwined, with more sophisticated play associated with more advanced language skills (Campbell, 2002; Rome-Flanders & Cronk, 2002). From 12 to 30 months of age, typically developing children evidence a shift from self-referenced play (e.g. drinking from a cup) to other-referenced play (e.g. giving a doll a drink), eventually demonstrating active-other play (e.g. the doll is drinking unaided; Rubin, Fein, & Vandenberg, 1983). This developmental progression forms the foundation for pretend play with peers; thus, delays in the development of language and solitary play may translate into impaired peer play, which may be associated with behaviour problems.

Co-occurrence of linguistic/behavioural problems

Relations between language difficulties and behaviour problems are generally modest among children younger than age three. Notably, two studies found that externalising behaviour problems were not reliably correlated with expressive language delay until after 30 months of age (Horwitz et al., 2003; Tervo, 2007). During this developmental period, language difficulties (receptive and expressive) are most likely associated with deficits in social competence, as opposed to externalising behaviours (Caulfield, Fischel, DeBaryshe, & Whitehurst, 1989; Horwitz et al., 2003; Irwin, Carter, & Briggs-Gowan, 2002; Paul, Looney, & Dahm, 1991; Ross & Weinberg, 2006; Tervo, 2007). Thus, given that decreased social competence is a common correlate of language delay among children from birth to age three, limited social–linguistic opportunities resulting in diminished social competence may mediate the pathway between early language difficulties and later behaviour problems.

Preschool-aged children

Linguistic developmental milestones for preschool-aged children include the production of longer and more complex sentences. By age three, children can use language to describe more abstract concepts, such as internal states and relationships (Berk, 2002) and add grammatical morphemes that contribute increased structural and semantic complexity (e.g. ‘-ing’ verb endings, simple prepositions, plural nouns; de Villiers & de Villiers, 1973). Questions, negatives, embedded sentences, and connectives joining two clauses also appear in preschool-aged children’s increasingly sophisticated speech. By the end of the preschool years, children are able to use most grammatical structures correctly.

The development of these linguistic competencies is critical for early school success. School entry represents a significant developmental milestone for preschoolers, who must form new relationships outside of the family, adjust to the expectations of teachers and classroom routines, follow directions and interact with peers during learning and play (Mendez, Fantuzzo, & Cicchetti, 2002; Olson & Hoza, 1993). Thus, among the most important stage-salient tasks for preschoolers is the development of self-regulatory strategies and positive peer relations (Liebermann, Giesbrecht, & Muller, 2007; Olson & Hoza, 1993). Typically developing children’s linguistic and communicative development forms the basis for meta-communication about play, planning for play, and the execution of complex social pretend play (Howes & Lee, 2006). Between 36 months and 48 months of age, preschoolers’ development of self-regulatory systems is characterised by dramatic improvements in error detection and ability to inhibit actions, which coincides with the development of frontal brain structures that occurs during this developmental period (Jones, Rothbart, & Posner, 2003).

Co-occurrence of linguistic/behaviour problems

One consistent research finding is that preschool-aged children with language difficulties continue to evidence deficits in social skills (Qi & Kaiser, 2004; Stanton-Chapman, Justice, Skibbe, & Grant, 2007), suggesting some continuity in the correlates of language difficulties from the toddler to preschool period. However, emotional and behavioural problems also become reliably and positively associated with language difficulties during preschool (Beitchman, Hood, Rochon, & Peterson, 1989; McCabe, 2005; Qi & Kaiser, 2004; Stanton-Chapman et al., 2007; Willinger et al., 2003), with more severe behavioural problems noted among children with receptive or pervasive language difficulties, compared to expressive language impairment (Beitchman et al., 1989; Estrem, 2005; McCabe, 2005; van Daal et al., 2007). Language difficulties may confer non-specific risk for the development of behavioural problems by limiting children’s exposure to social–linguistic opportunities or through other mediating variables. Thus, consideration of additional child-specific and contextual processes that may mediate or moderate these relations, and thereby contribute to particular outcomes, is necessary.

Multiple domains of risk and resilience

The integrative study of factors contributing both to risk and resilience – positive adaptation in the context of adversity – is fundamental to a developmental psychopathology perspective (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). Considering variables (e.g. mediators, moderators, shared risk factors) drawn from multiple domains permits a more holistic understanding of children’s adverse or resilient outcomes (Cicchetti & Dawson, 2002). Thus, we provide a multiple domain conceptual model of factors that may contribute to children’s risk and resilience in terms of the development of comorbidity. We focus on two potential child-specific shared risk factors (i.e. poor working memory and high temperamental anger/frustration). We also discuss several candidate moderator variables that include processes in the domains of: (1) language (i.e. type of language difficulty, adaptive communication); (2) emotion regulation; and (3) context (i.e. linguistic expressiveness in the home, parent–child interactional processes). We then consider two potential mediators of the relations between language and behavioural difficulties, namely, limited social–linguistic interactions and negative relationships with social figures. Depending on the degree to which these shared risk factors, moderating and mediating variables are present (e.g. high vs. low levels), these factors may confer risk or resilience.

We selected these processes because: (1) their interaction may confer more proximal risk for the development of co-occurring language and behavioural difficulties than other processes during the developmental periods under consideration, (2) these processes likely capture the transactional relations among children and their contexts, and (3) some of these processes may be amenable to intervention (e.g. adaptive communication, linguistic expressiveness in the home). We present a model that is one potential illustration of how to integrate these processes to provide a framework for understanding the development of linguistic and behavioural difficulties and their comorbidity.

Shared risk factors

Poor working memory

Working memory involves the storage and manipulation of information so that this information can guide subsequent responses (Hongwanishkul, Happaney, Lee, & Zelazo, 2005), and thus is important for verbal and behavioural output. In general, working memory is positively correlated with language achievement and production of complex spoken language (Adams & Gathercole, 1995; Wolfe & Bell, 2004); moreover, phonological working memory deficits have been well documented among children with language difficulties (Baddeley, Gathercole, & Papagno, 1998; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1990). Preschoolers’ working memory prospectively predicts vocabulary acquisition (Gathercole & Baddeley, 1989; Gathercole, Willis, Emslie, & Baddeley, 1992; Leclercq & Majerus, 2010) and is positively associated with spoken language comprehension, longer utterances, syntactic diversity, and lexical-semantic abilities (Adams, Bourke, & Willis, 1999; Adams & Gathercole, 2000; van Daal, Verhoeven, van Leeuwe, & van Balkom, 2008). The link between phonological working memory and vocabulary seems to be strongest in early childhood (Gathercole, Tiffany, Briscoe, Thorn, & The ALSPAC Team, 2005), which supports the inclusion of working memory in models focusing on word-learning during this developmental stage. Given phonological working memory’s importance for recognising and remembering phonemes, words, and phrases (Baddeley et al., 1998; Bannard & Matthews, 2008), working memory may be particularly important for processing simultaneous situational demands and limiting phonological memory decay when children are faced with challenging linguistic tasks (e.g. monitoring conversations, conversing, and playing simultaneously; Gillam, Cowan, & Marler, 1998). Poor working memory may make conversational exchanges challenging, possibly putting children at additional risk for missed social–linguistic opportunities and peer exclusion.

Working memory performance also has been linked to externalising behaviour problems, although in the externalising literature, working memory is often studied under the umbrella term of executive function (Senn, Espy, & Kaufmann, 2004). Several studies have demonstrated negative associations between disruptive behaviours and: (1) executive function performance among preschoolers (Bierman, Torres, Domitrovich, Welsh, & Gest, 2009; Cole, Usher, & Cargo, 1993; Hughes & Ensor, 2008; Hughes, White, Sharpen, & Dunn, 2000), and (2) poor working memory (Aronen, Vuontela, Steenari, Salmi, & Carlson, 2005; Hooper, Roberts, Zeisel, & Poe, 2003; Ripley & Yuil, 2005). Deficits in working memory may interfere with children’s ability to remember requests, follow directions, complete multi-step tasks, and engage in problem-solving skills, each of which may confer risk for behaviour problems (Gathercole, Durling, Evans, Jeffcock, & Stone, 2008). Taken together, these results establish an association between working memory and both language difficulties and behaviour problems.

Difficult temperament

The construct of difficult temperament has been most frequently associated with dimensions of negative emotionality (Bates, 1980; Prior, 1992), including frequency and intensity of anger and frustration (Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001). Low soothability, adaptability, and rhythmicity, as well as high activity level, also have been included in conceptualisations of difficult temperament (e.g. Pesonen, Räikkönen, Keskivaara, & Keltikangas-Järvinen, 2003; Szabó et al., 2008; Thomas & Chess, 1977). Broadly, difficult temperament has been shown to confer risk for externalising behaviour problems among young children (e.g. Campbell, 2002; Rothbart & Bates, 1998; Sanson, Hemphill, & Smart, 2004). Studies assessing individual dimensions of difficult temperament have demonstrated direct links between behaviour problems and: (1) soothability and anger (Szabó et al., 2008), (2) impulsivity and anger (Karreman, de Haas, van Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković, 2010), and (3) activity, low adaptability, and negative affect/emotionality (De Pauw, Mervielde, & Van Leeuwen, 2009). Among preschool-aged children, proneness to anger is associated with externalising behaviour problems (Eisenberg et al., 2001; Hayden, Klein, & Durbin, 2005; Rothbart, Derryberry, & Hershey, 2000; Rothbart et al., 2001) and low levels of prosocial behaviours (Denham, 1986).

With regard to children’s language development, lower levels of linguistic mastery have been reported among children with difficult temperament (Dixon & Shore, 1997; Dixon & Smith, 2000; Noel, Peterson, & Jesso, 2008; Slomkowski, Nelson, Dunn, & Plomin, 1992). Researchers have hypothesised that more flexible and easygoing temperamental styles promote parent–child interactions that are conducive to learning words and allow parents to scaffold their children’s emerging language skills (Noel et al., 2008). Thus, both working memory deficits and dimensions of difficult temperament, particularly a tendency to experience anger/frustration, may predispose young children to both externalising behaviour problems and disruptions in their language development, and consequently are conceptualised as shared risk factors for linguistic and behavioural comorbidity. However, other child-specific and contextual moderating variables, considered next, may exacerbate or buffer the effects of these risk factors.

Moderating variables: child-specific factors

Type of language difficulty

Generally, linguistic profiles that include receptive language-only or mixed receptive-expressive difficulties are associated with more severe behavioural and socio-emotional problems, compared to those with only expressive or articulation difficulties (Beitchman et al., 1989, 1996; Benner et al., 2002; Botting & Conti-Ramsden, 2000; McCabe, 2005; Tervo, 2007). Children with competent receptive language skills may evidence more resilient outcomes, even in the context of other risk factors, whereas poor comprehension may increase the likelihood of developing co-occurring language and behaviour problems. Given heterogeneity and differential impairment associated with these language difficulties, it is critical to consider the type and degree of language difficulty in a conceptual model of comorbid linguistic and behavioural difficulties.

Adaptive communication

Despite documented associations between expressive language difficulties and behavioural problems, children’s expressive language ability measured in a controlled testing situation may not correspond directly to their actual ability to communicate in everyday situations. Children’s levels of ‘adaptive communication’ – which we have operationalised to denote ‘real-world’ usage of language to convey one’s needs, feelings, and goals – may provide additional information about children’s linguistic functioning that is not captured by standardised language testing scores. For example, children with intact expressive language but low levels of adaptive communication may be less able to use their linguistic knowledge to navigate interpersonal challenges in the classroom, thus making it more likely that they will act out behaviourally. Conversely, children with below-average expressive language ability but appropriate adaptive communication may be able to apply words that they know appropriately to express their goals or wishes in various situations. Consequently, these children may be at decreased risk for behavioural problems relative to children with lower levels of adaptive communication.

In support of this possibility, several studies have demonstrated that behaviour problems can be reduced through the provision of training in adaptive communication skills (for a review, see Mirenda, 1997). For example, Vollmer, Northup, Ringdahl, LeBlanc, and Chauvin (1996) identified the function of tantrums among three language-delayed children (aged two to four years; e.g. maternal attention, access to preferred toys). They used this information to teach more adaptive communicative replacement behaviours to the children, whose tantrums subsequently decreased (Vollmer et al., 1996). In another study, functional communication training decreased the escalation of attention-seeking behaviour problems among children with developmental disorders (Reeve & Carr, 2000). Thus, adaptive communication may be an important protective factor to include in a conceptual model of comorbidity, as higher levels may buffer the development of behaviour problems among children with language difficulties.

Emotion regulation

Deficits in children’s ability to regulate their emotions have been linked frequently to externalising disorders (e.g. Calkins & Howse, 2004), diminished social competence (Eisenberg & Fabes, 2006; Mendez et al., 2002), and expressions of anger and frustration when faced with requests and demands (Eisenberg, Fabes, Nyman, Bernzweig, & Pinuelas, 1994). Given that preschool-aged children are faced with the developmental task of adjusting to a structured classroom-based routine, their capacity to inhibit the expression of negative emotions will influence their ability to benefit from early social and academic experiences.

There is likely a transactional relation between language skills and the voluntary regulation of emotions; moreover, these language and emotion regulation abilities are hypothesised to predict a variety of behavioural outcomes. For example, children’s use of non-hostile language-based strategies to manage their anger is associated with a lower intensity of anger and more constructive coping (Eisenberg et al., 1994). Moreover, children with lower levels of receptive vocabulary exhibit lower levels of emotional control, as well as lower levels of prosocial peer play (Fantuzzo, Sekino, & Cohen, 2004; Mendez et al., 2002). Indeed, the combination of difficulties with language and emotional control likely diminishes children’s abilities to resolve conflict and to benefit from social interactions (Liebermann et al., 2007).

Competent emotional self-regulation may protect against the development of cooccurring expressive language and externalising difficulties and thus serves as a protective factor in models of comorbid language and behaviour problems (Degnan, Calkins, Keane, & Hill-Soderlund, 2008). Children with language difficulties may experience frustration when they are unable to express their wants or needs. Consequently, they may be less receptive to verbal or play interactions, or they may exit these situations prematurely when they can no longer manage the frustration that arises, resulting in fewer social-linguistic opportunities and higher levels of behaviour problems (Bowman et al., 2006; Eisenberg et al., 1994; Rothbart et al., 2001). Poor frustration tolerance could also contribute to negative responses from caregivers, teachers and peers when rules or expectations for appropriate behaviour are not followed, which could initiate negative or coercive interactional patterns (Cole, Teti, & Zahn-Waxler, 2003).

Moderating variables: contextual factors

Multilevel, ecological models of development (e.g. Bronfenbrenner, 1979) indicate that child and contextual risk factors exert shared and interactive effects on children’s outcomes (Drabick, 2009; Rutter & Sroufe, 2000). Therefore, children’s immediate environmental contexts are likely to influence whether – and to what extent – linguistic, behavioural, or other risk processes lead to co-occurring linguistic and behavioural difficulties. To illustrate the effects of contextual factors, we consider linguistic expressiveness in the home setting and parent–child interactional processes.

Linguistic expressiveness in the home

Children’s expressive language skill is positively associated with the linguistic expressiveness and complexity available in the home (Fagan & Iglesias, 2000; Horwitz et al., 2003). However, parents of children with expressive language delay reportedly adjust the sophistication of their speech to their children’s expression, not comprehension, ability (Whitehurst et al., 1988), which may result in fewer opportunities for children with expressive language delays to gain advanced linguistic exposure. Lower levels of linguistic expressiveness in the home may also contribute to children’s behavioural problems, given that language is critical for the socialisation of emotion regulation (Stansbury & Zimmerman, 1999), which is negatively associated with behavioural problems (Calkins & Howse, 2004). Given these links between children’s language competencies and emotion regulation socialisation, parents who engage in fewer or less complex verbal interactions with their children may be less capable of supporting their children’s developing self-regulation in appropriate ways, setting the stage for later behaviour problems.

Parent–child interactional processes

Parental responsiveness in parent–child interactions (e.g. temporal contiguity, promptness) promotes early language development (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2006) and may mitigate the effects of poor working memory or difficult temperament among children with language difficulties. As such, parental responsiveness may promote resilience from co-occurring language and behaviour difficulties. However, children with language difficulties may be less likely to experience such mutually responsive parent–child interactions. In support of this possibility, toddlers’ lower levels of expressive language skills predicted lower levels of mother–child dyadic synchrony (Skuban, Shaw, Gardner, Supplee, & Nichols, 2006). Parents of children with language difficulties are likely to be more negative and less nurturing than parents of typically developing children (Carson, Perry, Diefenderfer, & Klee, 1999; Irwin et al., 2002; McDermott & Rourke, cited in Rourke & Fisk, 1981), as well as less sensitive than parents of children whose language difficulties have remitted (La Paro, Justice, Skibbe, & Pianta, 2004). Given that poor language comprehension is often viewed by parents as deliberate non-complicance, even among typical samples (Kaler & Kopp, 1990), children with language difficulties may be particularly likely to experience punishment from their parents (Moffitt, 1993; Tarter, Hegedus, Winsten, & Alterman, 1984). Thus, negative parental responses to language difficulties may be particularly important moderating variables to consider when studying language-behaviour problem comorbidity.

Similar to findings regarding child language difficulties, child behaviour problems are associated with disrupted, low-quality, inflexible, and poorly synchronised parent–child interactions (Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller, & Snyder, 2004; Skuban et al., 2006; Webster-Stratton & Eyberg, 1982). Children with high levels of negative emotionality and poor emotion regulation skills may be particularly challenging to engage and more likely to elicit negative, unresponsive, and/or punitive reactions from parents (Shaw & Bell, 1993). Children with externalising problems are also especially likely to experience harsh disciplinary strategies (Cunningham & Boyle, 2002; Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1998) that may further maintain or exacerbate behaviour problems (Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Mulvaney & Mebert, 2007). These findings likely represent transactional relations between parents’ disciplinary strategies and the severity of children’s behavioural presentations, such that children with more severe behaviour problems are likely to experience harsher control attempts from parents.

Aspects of parent–child interactions also likely interact with children’s difficult temperament to influence children’s linguistic and behavioural outcomes. Effects of responsive mother–child interactions on language are strongest among infants with lower levels of temperamental emotionality, suggesting that mothers’ facilitation of emotion regulation strategies could help easily frustrated children to engage in language-promoting activities (Karrass & Braungart-Rieker, 2003), and, consequently, promote resilience from co-occurring language and behavioural problems. Also, risk for externalising problems associated with harsh and/or insensitive parenting is significantly higher among children with challenging temperamental styles (Bradley & Corwyn, 2007; Paterson & Sanson, 1999; Rubin, Hastings, Chen, Stewart, & McNichol, 1998; van Aken, Junger, Verhoeven, van Aken, & Deković, 2007) and may be buffered by more positive parent–child interactions (Barron & Earls, 1984; Szabó et al., 2008). Thus, qualities of the parent–child interactional and linguistic context represent significant sources of variability in explaining the development of comorbid language and behaviour problems and may be linked to risk or resilience for this comorbid condition. For example, among children with either behavioural or linguistic difficulties, responsive parent–child interactions and/or higher levels of linguistic expressiveness in the home may promote resilience from co-occurring language and behaviour problems, whereas problematic parent–child interactions and low levels of linguistic expressiveness in the home may contribute to the development of co-occurring language and behaviour problems.

Mediators of transactions between language difficulties and behaviour problems

As noted, once language or behaviour difficulties are present, one set of difficulties may exacerbate, maintain, or lead to the development of the other. Moreover, the development of this comorbidity can involve multiple underlying processes. In addition to the potential risk factors and moderators presented thus far, alternative processes may mediate the associations among language and behavioural difficulties. One possible mechanism that may transmit the effects of language delay, and thereby lead to the maintenance or exacerbation of problem behaviours, is limited opportunity for social–linguistic interactions. In addition, sequelae of behaviour problems, such as impaired, maladaptive relationships with peers, teachers, and parents, may maintain poor oral language skills and increase the likelihood of further problem behaviours. We recognise that additional mediators of these relations are likely; however, we focus on these two mediational processes to illustrate proximal contextual factors that have been shown to predict language and behavioural difficulties.

Limited social–linguistic interactions

As reviewed earlier, poor social competence is a reliable correlate of behaviour problems among older infants and toddlers with expressive language difficulties, typically preceding the development of behaviour problems (Horwitz et al., 2003; Tervo, 2007). One explanation for these findings is that language difficulties may set the stage for later behaviour problems by limiting opportunities for children to engage in prosocial and interactive peer play and to learn verbal conflict resolution and emotion regulation strategies from competent peers. Consistent with this possibility, compared to their peers with typical language, children with language difficulties are more likely to be interrupted and ignored (Hadley & Rice, 1991; Wellen & Broen, 1982), to provide shorter or non-verbal responses (Rice, Sell, & Hadley, 1991), and to respond less frequently when addressed by both peers (Hadley & Rice, 1991) and adults (Bishop, Chan, Adams, Hartley, & Weir, 2000; Rosinski-McClendon & Newhoff, 1987). In addition, compared to their peers, children with specific language impairment appear more isolated in the classroom, are less likely to be addressed in peer interactions, are often excluded by peers, and have fewer and less satisfying peer relationships (Craig, 1993; Fujiki, Brinton, & Todd, 1996; McCabe, 2005; Rice et al., 1991).

Children’s engagement in play (e.g. prosocial, interactive, pretend play) has been linked to positive socio-emotional development (Fisher, 1992; Gagnon & Nagle, 2004), including stronger self-regulatory skills (Whitebread, Coltman, Jameson, & Lander, 2009), higher social engagement, and lower levels of aggressive behaviours (Fantuzzo et al., 2004). However, children with language difficulties are often poorly equipped to engage in socially competent and interactive peer play, which is associated with multiple linguistic competencies (Craig-Unkefer & Kaiser, 2002), including higher concurrent levels of receptive and expressive vocabulary (Cohen & Mendez, 2009; Fantuzzo et al., 2004; Mendez et al., 2002). Children with language difficulties are chosen less often as playmates for social pretend play activities (Gertner, Rice, & Hadley, 1994) and are less able to join ongoing play (Craig & Washington, 1993). Exclusion from peer play is likely to further intensify the social–linguistic delays of language-impaired children (Rice, 1993) and increase the likelihood that they will engage in aggressive or disruptive behaviours to achieve their interpersonal goals (Coie & Kupersmidt, 1983; Fantuzzo et al., 2004). Overall, these results suggest that limited opportunities for language-mediated social development may confer risk for behaviour problems in the context of language difficulties.

Negative relationships with social figures

Children with risk factors in the domains of temperament and/or language are at increased risk for behaviour problems and aversive interactional styles with parents, teachers and peers for a variety of reasons (Moffitt, 1993). Scaramella and Leve (2004) proposed an early childhood coercion model, which posits that children’s poor emotion regulation during the preschool period evokes harsh responses and displays of hostile emotions from parents, whose own emotional overarousal then reduces their ability to help their children to self-regulate. Because children are consequently less capable of self-regulation, future episodes of harsh parenting are more likely to be elicited during parent–child interactions. Moreover, parents’ negative emotional responses model and promote inappropriate self-regulatory behaviours, which children generalise to their interactions with other important social figures (e.g. peers, teachers) (Scaramella & Leve, 2004). Similarly, Patterson (1982, 1986) reported reciprocal relations between children’s aggressive or antisocial responses and parents’ use of aversive behaviours during parent–child interactions, which result in escalating coercive interchanges (i.e. increases in the magnitude of subsequent aversive responses by parents and children) over time. These coercive interchanges often culminate in the parent’s withdrawal from the situation. These cycles are thus negatively reinforcing for the parent (i.e. removal from the aversive situation) and positively reinforcing for the child (i.e. negative behaviours result in a desired outcome); as a result, these cycles are likely to be subsequently maintained and exacerbated across multiple interactions (Patterson, 1982, 1986).

Once present, behaviour problems and coercive interactional patterns elicit negative reactions from the social environment and thus promote the development of new problem areas (e.g. peer rejection; Patterson, 1993) that may impede further language development, maintain poor language skills, and/or preclude important social experiences that could buffer children from the risk associated with behaviour problems. Indeed, over time, children – particularly in the context of poor verbal skills – may be increasingly likely to apply this coercive interactional style to others, including teachers and peers. Disruptive, oppositional, or aggressive behaviour can be inadvertently reinforced in the classroom setting when these behaviours permit children to escape undesirable tasks or to receive attention from peers (Bierman, 2004). Teachers may become embroiled in coercive interchanges with disruptive children, leading to steep escalations in punishments, ineffective behavioural management, and more negative teacher–student relationships (Bierman, 2004). These coercive interactions with teachers may generalise across school years as well (e.g. from kindergarten to subsequent school years; Brendgen, Wanner, & Vitaro, 2006). Given linkages between pre-kindergarten teachers’ positive teaching interactions and children’s later language acquisition (Burchinal et al., 2008), such early, negative teacher–student relationships may place children at risk for disrupted language development.

Children’s engagement in coercive interactions with peers is also associated with rejection by the normative peer group (Coie & Kupersmidt, 1983; Snyder et al., 2008). Rejected children are more likely to play alone or with younger, unpopular, and less skilled peers (Ladd, 1983). These friendships may confer additional risk for poor outcomes, as partnerships comprised of children with low socio-emotional competence are less likely to promote prosocial skill development and may even be conflictual (Bierman, 2004). Perhaps more importantly, these affiliations with unskilled peers further limit opportunities for prosocial verbal interactions with competent peers and for the development of non-aggressive conflict resolution strategies.

An integrative model of comorbidity

An understanding of the complex interplay between language and behaviour is complicated by the likelihood that multiple processes are involved in the development and perpetuation of comorbidity. In general, the likelihood of whether children develop comorbid language-behaviour problems is affected by their levels of exposure to multiple risk and resilience processes, as well as interactions between child and contextual factors, consistent with a developmental psychopathology perspective (Drabick, 2009). As such, we propose an integrative model that considers reciprocal interactions among multiple processes (Figure 1). We suggest that difficult temperament and deficits in working memory act as initiating factors in the pathway that may culminate in comorbid language and behaviour problems. Specifically, children who are temperamentally prone to anger and frustration may be more likely to act out behaviourally, and to evidence difficulty participating in early academic and social interactions that would promote language skills. Poor working memory may preclude or lessen children’s abilities to be compliant with adult requests and to follow complex directions, as well as children’s acquisition of vocabulary words and memory for phonemes.

Figure 1.

Integrative model of linguistic and behavioural comorbidity.

However, associations among these risk factors and comorbid linguistic and behavioural difficulties depend on moderating contextual and child-specific factors, which may exacerbate risk or promote resilience. Specifically, children’s emotion regulation capacities, parents’ engagement in linguistically stimulating activities, and the quality of parent–child interactions are hypothesised to be significant moderators of these risk processes. Similarly, child-specific factors (i.e. type of language difficulty, adaptive communication) likely moderate the relations between linguistic and behavioural difficulties, and determine whether – and to what extent – these difficulties are translated into more serious impairments. Specifically, children with higher levels of adaptive communication may be able to compensate for deficits in structural language skills and to minimise the effects of peer rejection and decreased opportunities for social–linguistic interactions. In addition, higher levels of receptive language skills likely permit more successful navigation of peer relationships (Craig, 1993). Thus, higher levels of these moderating processes (i.e. more responsive parent–child interactions, higher adaptive communication) are hypothesised to promote resilience, whereas lower levels of these processes are expected to confer risk for co-occurring language and behavioural difficulties. Furthermore, at least two potential mechanisms may underlie a transactional relation between language and behaviour. Pervasive, negative relationships with peers and adults are proposed to mediate the pathway from behaviour problems to further language difficulties, whereas limited social–linguistic interactions are proposed to mediate the pathway from language difficulties to behaviour problems. Given the observed heterogeneity in this population of comorbid children, child-specific factors likely influence which pathways children follow. To expand on this possibility, we turn to how this model accounts for equifinality and multifinality in children’s outcomes.

Equifinality and multifinality

Equifinality refers to the potential for diverse pathways to lead to the same outcome, whereas multifinality is the potential for similar initiating factors to result in diverse outcomes (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996). These concepts can be applied to the proposed model. In terms of equifinality, children’s varying levels of shared risk factors and/or moderators may predispose them to follow distinct pathways that culminate in comorbidity. For example, children who evidence deficits in working memory may be more likely to evidence language difficulties as their primary domain of impairment, and thus to follow the trajectory from language difficulties to limited social–linguistic interactions, which predisposes them eventually to develop behaviour problems. Conversely, children with temperamental tendencies to experience anger may be more prone to develop behaviour problems initially, which subsequently may interfere with their ability to form supportive relationships and thereby affect their language skills. Children with severe deficits in both of these areas may have a primary pathway influenced by moderating contextual and emotion regulation factors. For example, a child with poor working memory and a difficult temperament may be at risk for comorbid behaviour and linguistic difficulties. However, if this child has a responsive parent who communicates consistent, clear expectations, he or she may evidence resilience from the development of co-occurring behaviour problems.

Accounting for multifinality is of particular importance in this comorbid population of children. Both contextual and child-specific factors can buffer risk (promote resilience) or exacerbate risk, such that children with similar levels of temperamental negative emotionality and working memory could evidence heterogeneous outcomes. For example, even in the context of poor working memory and high levels of temperamental anger, children may not evidence social impairment if they have adequate emotion regulation, receptive language skills, and/or parents who provide high levels of cognitive stimulation and exposure to oral language. Other children with poor working memory and high levels of temperamental anger in the context of multiply stressed parents and/or low levels of linguistic expressiveness in the home would be expected to show more severe behavioural outcomes. To capitalise on the proposed model’s array of moderators drawn from multiple domains, it will be important to identify configurations of risk and protective factors that are associated with particular developmental trajectories, recognising that different levels of one factor may be linked to risk or resilience (e.g. low vs. high levels of parental responsiveness) and that the effects of these factors will depend on the presence of other variables (e.g. child temperament, working memory). Such knowledge could improve prediction of children’s trajectories, early identification of risk, and prevention and intervention models for co-occurring linguistic and behavioural difficulties.

Implications of applying this framework

In the following sections, we present future research directions, as well as clinical and educational implications, based on the proposed model for the development of cooccurring behavioural and linguistic difficulties.

Future research directions

Given that the proposed model is predicated on reciprocal interactions among processes across multiple domains, future research should consider patterns of risk and protective factors as they are clustered within subgroups of individuals, rather than (or in addition to) testing these variables individually. Thus, we would encourage researchers studying linguistic and behavioural comorbidity to move beyond the ascertainment of main effects and correlational relations and to account for moderating and reciprocal influences among intrapersonal and contextual factors (Kazdin & Kagan, 1994). Indeed, previous studies have primarily relied on variable-centred analytic approaches (e.g. regression analyses) to understand language-behaviour relations, even though this approach assumes similar variable interrelations for all children within the sample. However, person-centred analytic approaches are capable of identifying relatively homogeneous, qualitatively distinct subgroups of children, who may follow different developmental pathways (Magnusson, 1998). Thus, a combination of variable- and person-centred analytic strategies is indicated for future research efforts in understanding linguistic and behavioural comorbidity. This combined analytic approach can facilitate both the identification of meaningful subgroups of children (person-centred; e.g. children who differ in their levels of behaviour and linguistic difficulties), as well as the examination of subgroup-specific variable interrelations (variable-centred; e.g. whether levels of difficult temperament, working memory, or linguistic expressiveness in the home differ among these subgroups of children).

Longitudinal studies are needed to identify qualitatively distinct trajectories of children’s externalising behaviour problems and language abilities over the course of multiple time points. Such studies could advance knowledge about the temporal relations between language and behavioural variables for specific subgroups of children, as well as provide information about the strongest predictors of developmental outcomes for different subgroups (e.g. negative emotionality, receptive language). Because such predictors may confer resilience from developing co-occurring behaviour problems in the context of language difficulties, the identification of these attributes could inform prevention programmes to promote children’s behavioural health in preschool. Such work also has the potential to identify optimal timing for intervention by noting timepoints during the year when subgroups of children evidence problems that may be somewhat impairing but not yet clinically significant. Finally, for those subgroups of children that evidence either increasing or decreasing trajectories of language and/or behaviour problems over time, studies should test predictors and mediators of change. Promising mediators of improvement could then be integrated into subgroup-specific interventions.

Clinical and educational implications

Given the heterogeneity in levels of behaviour problems, language abilities, and other moderating factors, the identification of socio-emotionally and linguistically distinct subgroups of children has important clinical implications for practitioners and educators. Knowledge of such subgroups could facilitate: (1) the identification of children for targeted early interventions, (2) the determination of children’s primary area of concern (i.e. language or behaviour), and (3) the individualisation of interventions in terms of content and/or format. For example, within the broader domain of expressive language difficulties, some children may require intensive, one-on-one work with basic expressive language skills (e.g. object naming), whereas others may need a group-based intervention focused on applying expressive skills to social situations (i.e. adaptive communication skills). Consistent with this suggestion, among preschool children with both socio-emotional and language difficulties, social-communicative improvements have been observed following a dyadic play-based intervention (Craig-Unkefer & Kaiser, 2002, 2003; Stanton-Chapman, Denning, & Jamison, 2008).

As briefly discussed, functional communication training (FCT) is indicated over other intervention strategies when a functional analysis of the child’s problem behaviours indicates that the behaviour serves a specific function, such as requesting attention or escape (e.g. Reeve & Carr, 2000). However, traditional speech-language therapy and/or dyadic social-communication intervention may be indicated when social-behavioural difficulties are more pervasive and not limited to specific situations. In addition, FCT may be more appropriate for preschoolers with below-average cognitive ability and/or broader developmental concerns (Reeve & Carr, 2000).

Children with language difficulties who also have higher levels of temperamental emotionality and/or impaired self-regulation skills may benefit from an emotion-based programme before pursuing traditional language therapy (Izard et al., 2008). Moreover, children with other constellations of risk factors, such as low home-based linguistic expressiveness and negative parent–child interactional processes, may be candidates for psychoeducation and behavioural parenting interventions, such as parent management training (e.g. Kazdin, 1997), parent–child interaction therapy (e.g. McNeil, Capage, Bahl, & Blanc, 1999), or instruction in responsive communication and positive behaviour management skills (Hancock, Kaiser, & Delaney, 2002) to improve parent–child relationships and thereby address behavioural and/or linguistic difficulties.

The proposed model also has implications for pre-kindergarten teachers and for the management of preschool classrooms. First, the model suggests that children with different levels and combinations of risk and protective factors require different classroom supports to promote language development. Given that children with higher baseline levels of expressive language derive the most benefit from social–linguistic interactions with peers (Mashburn, Justice, Downer, & Pianta, 2009), children with more severe language difficulties may require individualised teacher-directed language-focused play to improve expressive language abilities, in addition to special education services. As children’s language improves, they may be able to profit from peer-managed play. The second implication for teachers underscores the importance of good classroom management in supporting children’s linguistic and social-behavioural development. Links between competent peer interactions and expressive language improvement are strongest within well-managed preschool classrooms, likely because teachers are able to plan and monitor peer-managed language-based play and create a safe, structured setting (Mashburn et al., 2009). It will be important for pre-kindergarten programmes to provide in-service training, classroom supports, and continuing education opportunities for teachers to enhance and develop classroom management skills.

In sum, comorbidity between language difficulties and behaviour problems among young children, although widely documented, remains poorly understood. Multiple explanations for co-occurring language and behaviour problems are likely relevant. Thus, we proposed an integrative model using a developmental psychopathology framework that includes an array of potential underlying mechanisms and moderating factors that reciprocally interact to influence children’s developmental trajectories. Shared risk factors (deficits in working memory, dimensions of difficult temperament) are hypothesised to interact with child-specific and contextual variables to confer risk for or resilience from co-occurring language and behavioural problems through two underlying mechanisms, coercive social relationships and/or fewer opportunities for social-linguistic interactions. The further exploration of moderating, mediating, and shared risk and protective factors at multiple levels, in conjunction with both person- and variable-centred analytic strategies, is critical for the identification of factors that confer risk or resilience for the development of comorbid language and behavioural difficulties. Such information has the potential to inform aetiological models, educational practices, and individualised prevention and intervention efforts.

Notes on contributors

Johanna L. Carpenter is a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology at Temple University in Philadelphia, USA. Her programmatic research focuses on understanding the relations between children’s language ability and behaviour problems across developmental periods. She is currently completing her predoctoral internship in clinical child and pediatric psychology.

Deborah A.G. Drabick, PhD, is an associate professor of psychology at Temple University, with appointments in the clinical and developmental psychology programmes. Dr Drabick’s research considers conduct problems among youth using a developmental psychopathology perspective, and includes such areas as risk and resilience, prevention, comorbidity and contextual influences. Dr Drabick directs the Child Health and Behavior Study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and was an advisor to the DSM-V Disruptive Behavior Disorders Workgroup. Dr Drabick serves on the American Psychological Association’s Division 12 Science and Practice Committee and has won numerous awards for her mentoring and teaching.

References

- Adams A-M, Bourke L, Willis C. Working memory and spoken language comprehension in young children. International Journal of Psychology. 1999;34:364–373. [Google Scholar]

- Adams A-M, Gathercole SE. Phonological working memory and speech production in preschool children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1995;38:403–414. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3802.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams A-M, Gathercole SE. Limitations in working memory: Implications for language development. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2000;35:95–116. doi: 10.1080/136828200247278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronen ET, Vuontela V, Steenari MR, Salmi J, Carlson SM. Working memory, psychiatric symptoms, and academic performance at school. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2005;83:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A, Gathercole S, Papagno C. The phonological loop as a language learning device. Psychological Review. 1998;105:158–173. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.105.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannard C, Matthews D. Stored word sequences in language learning: The effect of familiarity on children’s repetition of four-word combinations. Psychological Science. 2008;19:241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron AP, Earls F. The relation of temperament and social factors to behavior problems in three-year-old children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1984;25:23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1984.tb01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE. The concept of difficult temperament. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1980;26:299–319. [Google Scholar]

- Beitchman JH, Hood J, Rochon J, Peterson M. Empirical classification of speech/language impairment in children: II. Behavioral characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28:118–123. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198901000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitchman JH, Wilson B, Brownlie E, Walters H, Inglis A, Lancee W. Long-term consistency in speech/language profiles: II. Behavioral, emotional, and social outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:815–825. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199606000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner GJ, Nelson J, Epstein MH. Language skills of children with EBD: A literature review. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2002;10:43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Berk LE. Child development. 6th ed. Allyn & Beacon; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL. Peer rejection: Developmental processes and intervention strategies. Guilford; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Torres MM, Domitrovich CE, Welsh JA, Gest SD. Behavioral and cognitive readiness for school: Cross-domain associations for children attending Head Start. Social Development. 2009;18:305–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D, Chan J, Adams C, Hartley J, Weir F. Conversational responsiveness in specific language impairment: Evidence of disproportionate pragmatic difficulties in a subset of children. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:177–199. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt-Eisengart I, Drabick DA, Monahan KC, Steinberg L. Sex differences in the longitudinal relations among family risk factors and childhood externalizing symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:491–502. doi: 10.1037/a0014942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom L. Language development and emotional expression. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1272–1277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botting N, Conti-Ramsden G. Social and behavioural difficulties in children with language impairment. Child Language Teaching and Therapy. 2000;16:105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman M, Barnett D, Johnson A, Reeve K. Language, school functioning, and behavior among African American urban kindergartners. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52:216–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Externalizing problems in fifth grade: Relations with productive activity, maternal sensitivity, and harsh parenting from infancy through middle childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1390–1401. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendgen M, Wanner B, Vitaro F. Verbal abuse by the teacher and child adjustment from kindergarten through grade 6. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1585–1598. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlie E, Beitchman JH, Escobar M, Young A, Atkinson L, Johnson C, Douglas L. Early language impairment and young adult delinquent and aggressive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:453–467. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000030297.91759.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Howes C, Pianta R, Bryant D, Early D, Clifford R, Barbarin C. Predicting child outcomes at the end of kindergarten from the quality of pre-kindergarten teacher-child interactions and instruction. Applied Developmental Science. 2008;12:140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Howse RB. Individual differences in self-regulation: Implications for childhood adjustment. In: Philippot P, Feldman RS, editors. The regulation of emotion. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. pp. 307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1995;36:113–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB. Behavior problems in preschool children. Guilford; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Spieker S, Burchinal M, Poe MD. Trajectories of aggression from toddlerhood to age 9 predict academic and social functioning through age 12. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson DK, Perry CK, Diefenderfer A, Klee T. Differences in family characteristics and parenting behavior in families with language-delayed and language-normal toddlers. Infant-Toddler Intervention. 1999;9:259–279. [Google Scholar]

- Catts HW. The relationship between speech-language impairment and reading disabilities. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1993;36:948–959. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3605.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield MB, Fischel JE, DeBaryshe BD, Whitehurst GJ. Behavioral correlates of developmental expressive language disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1989;17:187–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00913793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Dawson G. Editorial: Multiple levels of analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:417–420. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402003012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The past achievements and future promises of developmental psychopathology: The coming of age of a discipline. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JS, Mendez JL. Emotion regulation, language ability, and the stability of preschool children’s peer play behavior. Early Education and Development. 2009;20:1016–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Menna R, Vallance DD, Barwick MA, Im N, Horodezky NB. Language, social cognitive processing, and behavioral characteristics of psychiatrically disturbed children with previously identified and unsuspected language impairments. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:853–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Kupersmidt JB. A behavioral analysis of emerging social status in boys’ groups. Child Development. 1983;54:1400–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Teti LO, Zahn-Waxler C. Mutual emotion regulation and the stability of conduct problems between preschool and early school age. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Usher BA, Cargo AP. Cognitive risk and its association with risk for disruptive behavior disorder in preschoolers. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1993;22:154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Craig HK. Social skills of children with specific language impairment: Peer relationships. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1993;24:206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Craig HK, Washington JA. Access behaviors of children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1993;36:322–337. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3602.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig-Unkefer LA, Kaiser AP. Improving the social communication skills of at-risk preschool children in a play context. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2002;22:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Craig-Unkefer LA, Kaiser AP. Increasing peer-directed social-communication skills of children enrolled in Head Start. Journal of Early Intervention. 2003;25:229–247. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Boyle MH. Preschoolers at risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: Family, parenting, and behavioral correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:555–569. doi: 10.1023/a:1020855429085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Calkins SD, Keane SP, Hill-Soderlund AL. Profiles of disruptive behavior across early childhood: Contributions of frustration reactivity, physiological regulation, and maternal behavior. Child Development. 2008;79:1357–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA. Social cognition, prosocial behavior, and emotion in preschoolers: Contextual validation. Child Development. 1986;57:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- De Pauw SS, Mervielde I, Van Leeuwen KG. How are traits related to problem behavior in preschoolers? Similarities and contrasts between temperament and personality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:309–325. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers JG, de Villiers PA. A cross-sectional study of the acquisition of grammatical morphemes in child speech. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1973;2:267–278. doi: 10.1007/BF01067106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne G, Tremblay R, Boivin M, Laplante D, Perusse D. Physical aggression and expressive vocabulary in 19-month-old twins. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:261–273. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WE, Shore C. Temperamental predictors of linguistic style during multiword acquisition. Infant Behavior and Development. 1997;20:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WE, Smith PH. Links between early temperament and language acquisition. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2000;46:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Drabick DAG. Can a developmental psychopathology perspective facilitate a paradigm shift toward a mixed categorical-dimensional classification system? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009;16:41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Emotion regulation and children’s socioemotional competence. In: Balter L, Tamis-LeMonda CS, editors. Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues. Psychology Press; New York: 2006. pp. 357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Nyman M, Bernzweig J, Pinuelas A. The relations of emotionality and regulation to children’s anger-related reactions. Child Development. 1994;65:109–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrem TL. Relational and physical aggression among preschoolers: The effect of language skills and gender. Early Education and Development. 2005;16:207–231. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Iglesias A. The relationship between fathers’ and children’s communication skills and children’s behavior problems: A study of Head Start children. Early Education and Development. 2000;11:307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Sekino Y, Cohen HL. An examination of the contributions of interactive peer play to salient classroom competencies for urban Head Start children. Psychology in the Schools. 2004;41:323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald A, Thorpe K, Marchman VA. Blue car, red car: Developing efficiency in online interpretation of adjective-noun phrases. Cognitive Psychology. 2010;60:190–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher EP. The impact of play on development: A meta-analysis. Play and Culture. 1992;5:159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki M, Brinton B, Todd CM. Social skills of children with specific language impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1996;27:195–202. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2002/008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon SG, Nagle RJ. Relationships between peer interactive play and social competence in at-risk preschool children. Psychology in the Schools. 2004;41:173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher TM. Interrelationships among children’s language, behavior, and emotional problems. Topics in Language Disorders. 1999;19:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Baddeley AD. Evaluation of the role of phonological STM in the development of vocabulary in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Memory and Language. 1989;28:200–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Baddeley AD. Phonological memory deficits in language disordered children: Is there a causal connection? Journal of Memory and Language. 1990;29:336–360. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Durling E, Evans M, Jeffcock S, Stone S. Working memory abilities and children’s performance in laboratory analogues of classroom activities. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2008;22:1019–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Tiffany C, Briscoe J, Thorn A, The ALSPAC Team Developmental consequences of poor phonological short-term memory function in childhood: A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:598–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Willis CS, Emslie H, Baddeley AD. Phonological memory and vocabulary development during the early school years: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:887–898. [Google Scholar]

- Gershkoff-Stowe L, Smith LB. Shape and the first hundred nouns. Child Development. 2004;75:1098–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertner BL, Rice ML, Hadley PA. Influence of communicative competence on peer preferences in a preschool classroom. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1994;37:913–923. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3704.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervain J, Mehler J. Speech perception and language acquisition in the first year of life. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:191–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam RB, Cowan N, Marler JA. Information processing by school-age children with specific language impairment: Evidence from a modality effect paradigm. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:913–926. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4104.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS, de Mesquita PB. The relationship between language and cognitive development and emotional-behavioral problems in financially-disadvantaged preschoolers: A longitudinal investigation. Early Child Development and Care. 2000;162:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam WS, Shahar G. Expulsion and suspension rates and predictors in one state. Infants and Young Children. 2006;19:228–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley PA, Rice ML. Conversational responsiveness of speech- and language-impaired preschoolers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1991;34:1308–1317. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3406.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock TB, Kaiser AP, Delaney EM. Teaching parents of preschoolers at high risk: Strategies to support language and positive behavior. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2002;22:191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LJ, McLeod S, Berthelsen D, Walker S. Literacy, numeracy, and learning in school-aged children identified as having speech and language impairment in early childhood. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2009;11:392–403. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden EP, Klein DN, Durbin C. Parent reports and laboratory assessments of child temperament: A comparison of their associations with risk for depression and externalizing disorders. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2005;27:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T, Granic I, Stoolmiller M, Snyder J. Rigidity in parent-child interactions and the development of externalizing and internalizing behavior in early childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:595–607. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047209.37650.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollich GJ, Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM, Hennon E, Chung HL, Rocroi C, Brown E. Breaking the language barrier: An emergentist coalition model for the origins of word learning. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2000;65(3) Serial No. 262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongwanishkul D, Happaney KR, Lee WSC, Zelazo PD. Assessment of hot and cool executive function in young children: Age-related changes and individual differences. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28:617–644. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SR, Roberts JE, Zeisel S, Poe M. Core language predictors of behavioral functioning in early elementary school children: Concurrent and longitudinal findings. Behavioral Disorders. 2003;29:10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz L, Westlund K, Ljungberg T. Aggression and withdrawal related behavior within conflict management progression in preschool boys with language impairment. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2007;38:237–253. doi: 10.1007/s10578-007-0057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz SM, Irwin JR, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Heenan JM, Mendoza J, Carter AS. Language delay in a community cohort of young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:932–940. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046889.27264.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]