Parents’ preference for sons is common in countries in East Asia through South Asia, to the Middle East and North Africa. Sons are preferred because they have a higher wage-earning capacity (especially in agrarian economies), they continue the family line and they usually take responsibility for care of parents in illness and old age.1 There are also specific local reasons for son preference: in India, the expense of the dowry; and in South Korea and China, deep-rooted Confucian values and patriarchal family systems.2

For centuries, son preference has led to postnatal discrimination against girls; this has resulted in practices ranging from infanticide to neglect of health care and nutrition, often ending in premature mortality.3 But in the 1980s, ultrasound technology started to become available for diagnostic purposes in many Asian countries, and the opportunity to use the new technology for sex selection was soon exploited. In countries where there is a combination of son preference, a small-family culture and easy access to sex-selective technologies, very serious and unprecedented sex-ratio imbalances have emerged. These imbalances are already affecting the reproductive age groups in a number of countries, most notably China, South Korea and parts of India.1,3,4

The sex ratio at birth (SRB) is defined as the number of boys born to every 100 girls, and is remarkably consistent in human populations at around 105 male births to every 100 female births. South Korea was the first country to report a very high SRB, because the widespread uptake of sex-selective technology in South Korea preceded that of other Asian countries.4 The SRB started to rise in South Korea in the mid-1980s, and by 1992 the SRB was reported to be as high as 125 in some cities.

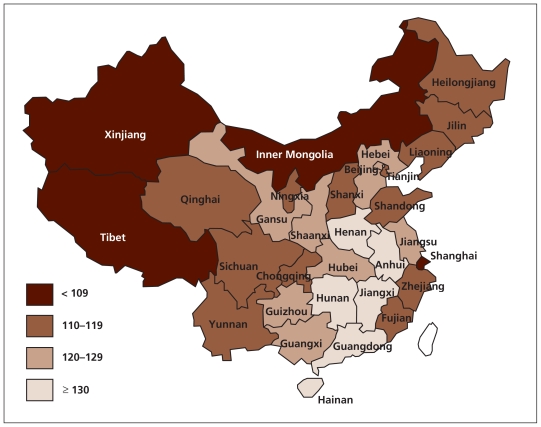

China soon followed. Here, the situation is complicated by the one-child policy, which has undoubtedly contributed to the steady increase in the reported SRB from 106 in 1979, to 111 in 1990, 117 in 2001 and 121 in 2005.5 Because of China’s huge population, these ratios translate into very large numbers of excess males. In 2005 it was estimated that 1.1 million excess males were born across the country, and that the number of males under the age of 20 years exceeded the number of females by around 32 million.5 These overall figures conceal wide variations across the country. Figure 1 shows these variations at the regional level: the SRB is over 130 in a strip of provinces from Henan in the north to Hainan in the south, and it is close to normal in the large, sparsely populated provinces of Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and Tibet. High reported SRBs can result from female infanticide and underregistration of female births. However, in China, there is now clear evidence that sex-selective abortion accounts for the overwhelming number of “missing women.”2,3,5

Figure 1:

Sex ratios in the one-to-five age group in Mainland China in 2005. Adapted by permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. Zhu WX, Li L, Hesketh T. China’s excess males, sex selective abortion and one child policy: analysis of data from 2005 national intercensus survey. BMJ 2009;338:b1211.5

In India there are also marked regional differences in SRB. Incompleteness of birth registration makes the SRB difficult to calculate accurately, but using the closely related ratio of boys to girls under the age of six years, it is found that there are distinct regional differences across the country. Several states in the north and west such as Punjab, Delhi and Gujarat have sex ratios as high as 125, but in the south and east, several states such as Kerala and Andhra Pradesh have sex ratios of around 105.3

A consistent pattern in all three countries is the marked trend related to birth order and the influence of the sex of the preceding child. If the first child is a girl, couples will often use sex-selective abortion to ensure a boy in the second pregnancy, especially in areas where low fertility is the norm. A large study in India showed that for second births with one preceding girl the SRB is 132, and for third births with two previous girls it is 139, whereas sex ratios are normal where the previous child was a boy.6 In China this effect is even more dramatic, especially in areas where the rural population are allowed a second child only after the birth of a girl, as is the case in some central provinces. The SRB across the country for first-order births is 108, for second-order births it is 143 and for the (albeit rare) third-order births it is 157.5

Consequences of high sex ratios

Prenatal determination of sex became accessible only in the mid-1980s, and later than that in rural areas; therefore, the large cohorts of surplus young men have only now started to reach reproductive age. Because of this, the consequences of this male surplus in the reproductive age group are still largely speculative. However, there is no disputing that over the next 20 years in large parts of China and India there will be a 10%–20% excess of young men. These men will be unable to marry, in societies where marriage is regarded as virtually universal, and where social status and acceptance depend, in large part, on being married and creating a new family.7 When there is a shortage of women in the marriage market, women have the opportunity to “marry up,” inevitably leaving the least desirable men with no marriage prospects.8 The result is that most of these men who are unable to marry are poor, uneducated peasants. In China these men are referred to as “guang gun,” meaning “bare branches,” signifying their inability to bear fruit. In China, 94% of all unmarried people aged 28–49 are male, and 97% of them have not completed high school.9

A number of assumptions have been made about the effects of the male surplus on these men who are unable to marry. First, it has been assumed that the lack of opportunity to fulfill traditional expectations of marrying and having children will result in low self-esteem and increased susceptibility to a range of psychologic difficulties.9 It has also been assumed that a combination of psychologic vulnerability and sexual frustration may lead to aggression and violence in these men.10 There is good empirical support for this prediction: cross-cultural evidence shows that the overwhelming majority of violent crime is perpetrated by young, unmarried, low-status males.11 In China and parts of India the sheer numbers of unmated men are a further cause for concern. Because they may lack a stake in the existing social order, it is feared that they will become bound together in an outcast culture, turning to antisocial behaviour and organized crime, thereby threatening societal stability and security.9 But as yet there is limited evidence for these hypotheses. Our own ongoing research in this area in China suggests that most of these men do indeed have low self-esteem, are inclined to depression and tend to be withdrawn. But there is no evidence that they are prone to aggression or violence, nor are reports of crime and disorder any higher in areas where there are known to be excess men. This may be because there is not yet a large enough critical mass of unmated men to have an impact, or because the assumptions about male aggression do not apply in this context.

It is also thought that large numbers of excess men will lead to an expansion of the sex industry. The sex industry has expanded in India and China in the last decade.12,13 However, the part played by a high sex ratio in this expansion is impossible to isolate; there is no evidence that numbers of sex workers are greater in areas with high sex ratios. The recent rise in numbers of sex workers in China has been attributed more to increased socioeconomic inequality, greater mobility and a relaxation in sexual attitudes than an increase in the sex ratio.14

There may also be positive aspects of this easy access to sex selection. First, access to prenatal sex determination probably results in an increase in the proportion of wanted births, leading to less discrimination against girls and lower female mortality.15 India, South Korea and China have all reported reductions in differential mortality in the last decade.3,16 Second, it has been argued that an imbalance in the sex ratio could be a means to help to reduce growth in the population.17 Third, as numbers of women in society fall, they become more highly valued and their social status increases.18 Not only will this benefit the women’s self-esteem, mental health and well-being, but the improved status of women should result in reduced son preference, with fewer sex-selective abortions and an ultimate rebalancing of the sex ratio.1

The policy response

Nothing can realistically be done to reduce the current excess of young males, but much can be done to reduce sex selection now, which will benefit the next generation. Realization of the potentially disastrous effects of this distortion in the sex ratio has led governments to take action. There are two obvious policy approaches: to outlaw sex selection and to address the underlying problem of son preference.

There are already laws forbidding fetal sex determination and sex-selective abortion in China, India and South Korea. But only in South Korea has the law been strongly enforced. As early as 1991, physicians in Seoul had their licences suspended for performing sex determination, with a resulting fall in the SRB from 117 to 113 in the following year.4 In South Korea this enforcement, along with public awareness campaigns, contributed to a reduction in the SRB from a high of 118 in 1990 to 109 in 2004.19 The fact that in China and India sex-selective abortion is still carried out with impunity, by medical personnel, usually qualified doctors, in hospitals and clinics, not in backstreet establishments, makes the failure of government to enforce the law all the more surprising. However, although sex-selective abortion is illegal, abortion itself is readily available, especially in China, and it is often difficult to prove that an abortion has been carried out on sex-selective, as opposed to family-planning, grounds.

China’s successful Care for Girls publicity campaign, which includes billboards, focuses on the value of female children and the problems facing the over-abundance of young men.

Image courtesy of T. Hesketh

To successfully address the underlying issue of son preference is hugely challenging and requires a multifaceted approach. In China, large public awareness campaigns, including poster and media campaigns, have focused on gender equity and the advantages of having female children. Recognition that intense intervention would be necessary to change these centuries-long traditions led to the Care for Girls campaign, instigated in 2003 by China’s National Population and Family Planning Commission. This campaign is a comprehensive program of measures, initially conducted in 24 counties in 24 provinces, which aims to improve perceptions of the value of girls and emphasizes the problems facing young men in finding brides. In addition, there has been provision of a pension for parents of daughters in rural areas. The results have been encouraging: in 2007, a survey showed that the campaign had improved women’s own perceived status and that stated son preference had declined. In one of the participating counties in Shanxi province, the SRB reduced from 135 in 2003 to 118 in 2006.20

Evidence from areas outside Asia strongly supports the notion that higher status for women leads to less-traditional gender attitudes and lower levels of son preference.21 The Chinese government has already made important moves toward gender equity in terms of social and economic rights. In 1992, the Law on the Protection of Rights and Interests of Women ensured equal legal rights for women in politics, culture, education, work, some property rights and marriage.22 These measures, together with socioeconomic improvements and modernization, have led to improvements in women’s status, which is gradually influencing traditional gender attitudes.19

But the sex ratio is persistently very high, so other policy options should be considered. The first relates to relaxation of the one-child policy. There has been gradual relaxation over the past decade. In large urban centres, if a husband and wife were both only children, two children are permitted. Starting in late 2011, this exception will apply if either spouse was an only child, if they reside in one of five large eastern provinces, which will massively increase the number of couples who will be allowed two children. In itself, this will probably have only a small effect on the sex ratio, because the high sex ratio is a greater problem in rural areas. But this signals a considerable relaxation in the previously strictly applied one-child rule in urban areas. In rural areas, a similar relaxation, especially to allow a third child after two girls, could lead to a substantial reduction in the sex ratio. The greatest contribution to the high sex ratio is in second-order births in rural areas. Evidence from studies that have explored preferred family size suggests that fears of a resulting rural population explosion would be unfounded, because a small minority of couples claim to want more than two children.23

The second policy option addresses the underlying problem of the value of female children. Women in rural China still marry into their husband’s family and cannot inherit family land, so daughters are often perceived as having “no value” to parents. In urban areas these traditions of inheritance have broken down and gender discrimination has decreased. It has been argued that changes in these laws in rural China could fundamentally influence attitudes about the value of women, which could lead, in turn, to a decrease in the sex ratio.2

The future

Despite the grim outlook for the generation of males entering their reproductive years over the next two decades, there are encouraging signs. In South Korea the sex ratio has already declined markedly, and China and India are both reporting incipient declines. In China, the SRB for 2008 was reported as 119, down from a peak of 121, and 14 provinces with high sex ratios are beginning to show a downward trend. India is now reported to have an SRB of about 113, down from a peak of about 116.19

However, these incipient declines will not filter through to the reproductive age group for another two decades, and the SRBs in these countries remain high. It is likely to be several decades before the SRB in countries like India and China are within normal limits.

Key points

In China, son preference and sex-selective abortion have led to 32 million excess males under the age of 20 years.

Men for whom marriage is unavailable are assumed to be psychologically vulnerable and may be prone to aggression and violence.

Policy-makers are addressing some causes of the high sex ratio at birth, but more could be done.

It will be several decades before the sex ratio at birth in countries like India and China is within normal limits.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Therese Hesketh declares that her institution has received grants or has grants pending from the Department for International Development, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Wellcome Trust. None declared by Li Lu or Wei Xing.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the content of the article. Therese Hesketh drafted the article, which Li Lu and Zhu Wei Xing revised. All authors approved the final version submitted for publication.

References

- 1.Hesketh T, Zhu WX. Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: causes and consequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103: 13271–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das Gupta M, Jiang L, Xie Z, et al. Why is son preference so persistent in East and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea. J Dev Stud 2003;40:153–87 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sen A. Missing women revisited. BMJ 2003;327:1297–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park CB, Cho NH. Consequences of son preference in a low fertility society: imbalance of the sex ratio at birth in Korea. Popul Dev Rev 1995;21:59–84 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu WX, Li L, Hesketh T. China’s excess males, sex selective abortion and one child policy: analysis of data from 2005 national intercensus survey. BMJ 2009;338:b121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jha P, Kumar R, Vasa P, et al. Low male-to-female sex ratio of children born in India: national survey of 1.1 million households. Lancet 2006;367:211–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buss DM, Schmitt DP. Sexual strategies theory: an evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychol Rev 1993;100:204–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng Y, Tu P, Gu B, et al. Causes and implications of the recent increase in the reported sex ratio at birth in China. Popul Dev Rev 1993;19:283–302 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson V, Den Boer A. A surplus of men, a deficit of peace. Int Secur 2002;26:5–38 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barber N. The sex ratio as a predictor of cross-national variation in violent crime. Cross-Cultural Res 2000;34:264–82 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messner SF, Sampson RJ. The sex ratio, family disruption and rates of violent crime: the paradox of demographic structure. Soc Forces 1991;69:693–713 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dandona R, Dandona L, Kumar GA, et al. Demography and sex work characteristics of female sex workers in India. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2006;6:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker JD, Henderson GE, Wang TF, et al. Surplus men, sex work and the spread of HIV in China. AIDS 2005;19:539–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hesketh T, Zhang J, Dong JQ. HIV knowledge and risk behaviour of female sex workers in Yunnan Province, China. AIDS Care 2005;17:958–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodkind D. On substituting sex ratio strategies in east Asia: Does prenatal sex selection reduce postnatal discrimination? Popul Dev Rev 1996;22:111–25 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klasen S, Wink C. A turning point in gender bias in mortality? An update on the number of missing women. Popul Dev Rev 2002;28:285–312 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold F. The effect of son preference on fertility and family planning: empirical evidence. Popul Bull UN 1987;23:44–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.South SJ, Trent K. Sex ratios and women’s roles: a cross-national analysis. Am J Sociol 1988;93:1096–115 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das Gupta M, Chung W, Li S. Evidence for an incipient decline in numbers of girls in China and India. Popul Dev Rev 2009;35: 401–16 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li SZ, Yan SH. A special study on “care for girls” campaign [article in Chinese]. Population and Family Planning 2008;10:23–4 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolezendahl C, Myers D. Feminist attitudes and support for gender equality: opinion change in women and men, 1974–1998. Soc Forces 2004;83:759–90 [Google Scholar]

- 22.All-China Women’s Federation Laws and regulations. Available: www.women.org.cn/english/english/laws/02.htm (accessed 2011 Feb. 16).

- 23.Ding QJ, Hesketh T. Family size, fertility preferences, and sex ratio in China in the era of the one child family policy: results from national family planning and reproductive health survey. BMJ 2006;333:371–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]