Abstract

Background:

Immigration has been and remains an important force shaping Canadian demography and identity. Health characteristics associated with the movement of large numbers of people have current and future implications for migrants, health practitioners and health systems. We aimed to identify demographics and health status data for migrant populations in Canada.

Methods:

We systematically searched Ovid MEDLINE (1996–2009) and other relevant web-based databases to examine immigrant selection processes, demographic statistics, health status from population studies and health service implications associated with migration to Canada. Studies and data were selected based on relevance, use of recent data and quality.

Results:

Currently, immigration represents two-thirds of Canada’s population growth, and immigrants make up more than 20% of the nation’s population. Both of these metrics are expected to increase. In general, newly arriving immigrants are healthier than the Canadian population, but over time there is a decline in this healthy immigrant effect. Immigrants and children born to new immigrants represent growing cohorts; in some metropolitan regions of Canada, they represent the majority of the patient population. Access to health services and health conditions of some migrant populations differ from patterns among Canadian-born patients, and these disparities have implications for preventive care and provision of health services.

Interpretation:

Because the health characteristics of some migrant populations vary according to their origin and experience, improved understanding of the scope and nature of the immigration process will help practitioners who will be increasingly involved in the care of immigrant populations, including prevention, early detection of disease and treatment.

Migration is an important component of globalization. International migration is estimated at 200 million people,1 and the volume of migration continues to increase. Between 1990 and 2005, global migrants increased by some 33 million people, with the largest growth observed in the developed world. The movement of populations of this size has important implications for health practitioners, health systems2 and the health of individuals.3,4

Health status is associated with quality of life and use of formal and informal health services.5 Overall, immigrants appear to be healthier than the Canadian-born population, by virtue of being capable, both physically and mentally, of successfully moving themselves, and often their families, from one country to another.6 However, over time, this healthy immigrant effect is lost.7

Health status is not equivalent across all subgroups of immigrants. Certain migrant populations experience a higher risk of infectious diseases, cancer, diabetes and heart disease, which has clinical implications for those providing care to migrant communities.6 The health of migrants is a product of environmental, economic, genetic and socio-cultural factors related to when people migrated to Canada, where and how they lived in their original home country, and how and why they migrated. Their health is also influenced by postmigration factors involving integration into their new place of residence, employment, education and poverty, as well as the accessibility and responsiveness of health practitioners and responsiveness of the Canadian health care system to immigrants’ health needs.8

Migration medicine is complicated by the use of similar terms, such as immigrant, refugee or migrant, for what are, in reality, different populations. This article will use standard Canadian immigration terminology. To help primary care practitioners interpret the clinical preventive recommendations of the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health, we aimed to identify demographics, health status reports, access to health care and health system implications of migrant populations in Canada.

Methods

We designed a search strategy in consultation with the methods team of the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health and with the assistance of experts in migration medicine. We searched for systematic reviews, national population health studies and national statistics to determine immigration selection practices, demographics, health status and health system implications of migration to Canada.

Our initial search sought systematic reviews reporting on health status of immigrants in Canada and demographic data from online databases: Ovid MEDLINE (1996 to Sept. 1, 2009) and the websites of the Centers for Disease Control (www.cdc.gov), Public Health Agency of Canada (www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/index-eng.php), World Health Organization (www.who.int), International Organization of Migration (www.iom.int), Statistics Canada (www.statcan.gc.ca), and Citizenship and Immigration Canada (www.cic.gc.ca). Searches were limited to the English language, and keywords included immigrants, refugees, migration health, asylum seekers, demographics, primary health care and health systems. We selected demographic data based on recency (most recent national demographic data on immigration) and relevance for our key questions. We appraised eligible systematic reviews using the critical appraisal tool of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Evidence to assess systematic approach, transparency, quality of methods and relevance.

Our initial search identified one relevant systematic review on immigrant health status from 2007,6 and we updated this review with a search of Ovid MEDLINE from Jan. 1, 2007 to Jan. 1, 2010, for national population surveys and cohort studies that described health characteristics and health status for Canadian immigrants and refugees. Two reviewers selected studies on the basis of relevance to key questions and quality of national population study using appraisal tools from the Cochrane Collaboration.9 Sufficient definition of migrant populations (e.g., refugees, refugee claimants, asylum seekers, immigrants) to allow for comparison was a prerequisite for inclusion. We compared use of terminology and population characteristics in the literature to ensure consistency. Finally, we provided a descriptive synthesis of the results.

Results

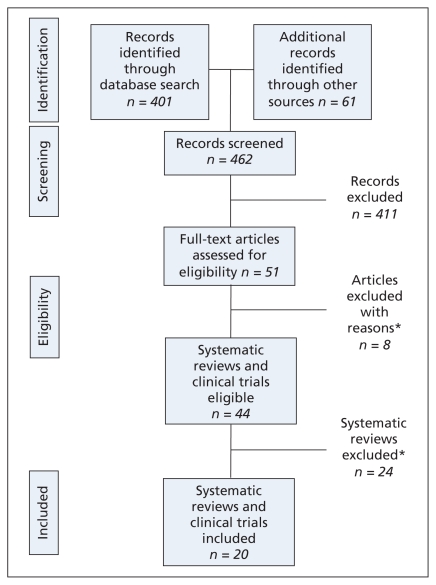

Statistics Canada and Citizenship and Immigration Canada provided the most recent and accurate data on Canadian immigration demographics and selection processes. International migration statistics were available on the Centre for Disease Control and International Organization of Migration websites. The initial search for systematic reviews on health status yielded one recent review that described health characteristics of immigrants to Canada.6 This review (2001–2007) identified and described 12 national population studies on health status.5,10–18 Our updating search identified eight additional national population studies describing health status of immigrants and refugees to Canada19–26 (Figure 1). Health and demographic data on non-status people (illegal aliens) in Canada was very limited.

Figure 1:

Search and selection flow chart. *Low quality or lack of national sample, availability of more recent data or lack of relevance to immigrant health status.

What are the Canadian immigration categories?

Two main administrative classifications are related to foreign nationals arriving in Canada. Temporary residents are people who are visiting, studying or working in Canada but who maintain their own nationality and their ability to return to their place of origin. Permanent residents come to Canada to resettle. Each of these two categories classifies various individuals and further subclassifies administrative groups (Table 1).7,27–30

Table 1:

| Immigration category | Annual migration (no.)† |

|---|---|

| Permanent residents27 | |

| Economic class (business and economic migrants) | 131 000 |

| Family class (family reunification) | 66 000 |

| Humanitarian class (refugees resettled from abroad or selected in Canada from refugee claimants) | 28 000 |

| Others | 11 000 |

| Total | 237 000 |

| Temporary residents27 | |

| Migrant workers | 165 000 |

| International students | 74 000 |

| Refugee claimants (those arriving in Canada and claiming to be refugees)27 | 28 000 |

| Other temporary residents27 | 89 000 |

| Total27 | 357 000 |

| Other migrants | |

| Total irregular migrants,‡ not annual migration29 | ~ 200 000 |

| Visitors28 | ~ 30 100 000 |

Numbers rounded to nearest 1000.

Unless otherwise indicated.

No official migration status. This population includes those who have entered Canada as visitors or temporary residents and remained to live or work without official status. It also includes those who have entered the country illegally and have not registered with authorities or applied for residence.

Immigrants

Canadian immigration has evolved into a regulated process designed to select and facilitate the arrival of those who would best fit labour and demographic needs. Currently, between 225 000 and 250 000 immigrants arrive in Canada every year. In contrast, the United States, with a population 10 times that of Canada, accepts approximately 1 000 000 legal permanent residents per year,30 and Australia, a nation with a population of approximately 22 million, received 192 000 new immigrants in 2006.31

Humanitarian migrants (refugees and refugee claimants)

Refugees are selected for permanent residence in Canada in one of two ways. They may be selected from groups of refugees outside Canada or from people already in Canada who claim refugee status after arrival (refugee claimants). In 2007, some 11 200 refugees arrived in Canada from abroad.27 Others, known as refugee claimants, arrive in Canada and ask to be considered refugees on the basis of fear of returning to their country of origin. In 2007, nearly 12 000 refugees received acceptance to Canada via this route. The process for filing a refugee claim and completing the determination process in Canada can take some time. As of March 2008, some 42 000 claims were pending adjudication, representing people who had arrived in Canada and requested refugee status.32 In the United States, approximately 100 000 refugees and people seeking asylum legally arrived in 2008;30 in Australia, approximately 14 000 refugees arrived in 2006.31

Temporary residents

Another growing group of migrants in Canada is temporary residents. This group includes temporary workers (agriculture, construction, fisheries, etc.) and students. These groups pay to have access to provincial government health insurance programs. There are several health issues of concern for these populations at both personal and occupational levels,33 but they are beyond the scope of this review.

Millions of visitors from the United States and other locations visit Canada every year. They do not have access to government health insurance programs.

Those residing in Canada without official status

Some people have no official immigration status or access to government programs (i.e., provincial or territorial health insurance, Interim Federal Health Insurance Program, government-supported resettlement services). These people are often referred to as “nonstatus persons” or “irregular migrants.” The exact number of irregular migrants in Canada is unknown but is estimated to be 200 000.29 People without status face serious barriers to health care,34 but empirical evidence as to the health needs and risks of this population is limited.35

Does medical screening occur during the migration process?

Canadian immigration legislation36 requires that all permanent residents, including refugees, refugee claimants and some temporary residents, receive an immigration medical examination. Determination of which temporary residents or visitors require an immigration medical examination is based on their place of origin, the duration of the visit (longer than six months) and occupation (workers in close contact with others). More information on the immigration medical examination is available at the Citizenship and Immigration Canada website (www.cic.gc.ca/english/information/medical/index.asp).

Refugee claimants, who arrive in Canada to make a refugee claim, have their immigration medical examination after their arrival. All others are examined outside Canada as part of the application process. The costs of the examination are borne by applicants, except in the case of refugee claimants examined in Canada, for whom the Interim Federal Health Insurance Program covers the costs. Additional information on these costs is available at www.fasadmin.com/images/pdf/%7B593DF72A-D33E-496B-ABF5-27511E2BE550%7D_IFH_Manual_English_06.pdf

The immigration medical examination is a mandatory component of the immigration application process and, when successfully completed, is valid for 12 months. Screening is undertaken to assess potential burden of illness and a limited number of public health risks. It is not designed to provide clinical prevention services, and it is linked to ongoing surveillance or notification actions only for tuberculosis, syphilis and HIV.37

Who migrates to Canada?

Before 1960, nearly all new arrivals in Canada arrived from Western and Central Europe and the United States.38 As the 20th century progressed, the forces of political and social change created dramatic shifts in the geographic origin of immigrants coming to Canada. Table 238 highlights the rank order of source country for new permanent residents to Canada between 1981 and 2006.

Table 2:

Country of birth of recent immigrants to Canada by census year38

| Rank | Census year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2001 | 1996 | 1991 | 1981 | |

| 1 | People’s Republic of China | People’s Republic of China | Hong Kong | Hong Kong | United Kingdom |

| 2 | India | India | People’s Republic of China | Poland | Vietnam |

| 3 | Philippines | Philippines | India | People’s Republic of China | United States of America |

| 4 | Pakistan | Pakistan | Philippines | India | India |

| 5 | United States of America | Hong Kong | Sri Lanka | Philippines | Philippines |

| 6 | South Korea | Iran | Poland | United Kingdom | Jamaica |

| 7 | Romania | Taiwan | Taiwan | Vietnam | Hong Kong |

| 8 | Iran | United States of America | Vietnam | United States of America | Portugal |

| 9 | United Kingdom | South Korea | United States of America | Lebanon | Taiwan |

| 10 | Colombia | Sri Lanka | United Kingdom | Portugal | People’s Republic of China |

The 2006 Canadian Census reflected the sustained effects of two and a half decades of uninterrupted immigration: nearly 6.2 million people, or 19.8% of the total population, were born outside the country. The situation is similar to that in Australia, where in the 2006 Census, 22.2% were foreign born.39 These proportions are nearly twice that of the United States, where the percentage of the legal foreign-born population represents approximately 12% of the total population.40 The 2006 Canadian Census38 documented that between 2001 and 2006, Canada’s foreign-born population increased by 13.6% — a rate of increase that was four times higher than the 3.3% growth rate for the Canadian-born population. Over the next decade, rates of growth in migrant populations from West Asia, Korea and Arab countries are expected to increase; the largest groups will continue to be South Asians and Chinese.41

Unlike the patterns of immigration in the early 20th century, immigration is now increasingly urban.38 As a result of this trend in immigration, the foreign-born population of Toronto in 2006 was 45.7%, Vancouver 39.6% and Montréal 20.6%.42 Table 327 highlights settlement by city.

Table 3:

Percentage of total annual migration by city of settlement27

| City | Proportion of annual migration (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 2007 | |

| Toronto | 43.9 | 36.8 |

| Montreal | 12.8 | 16.4 |

| Vancouver | 18.4 | 13.9 |

| Calgary | 3.4 | 4.7 |

| Winnipeg | 1.4 | 3.6 |

| Edmonton | 2.2 | 2.8 |

| Ottawa-Gatineau | 3.0 | 2.4 |

| Hamilton | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| Kitchener | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| London | 0.8 | 1.0 |

How healthy are immigrants and refugees?

The health of migrant populations is determined by factors intrinsic to the migration process: premigration, migration and postmigration resettlement, as well as social determinants of health. We identified 20 population health studies that analyzed data from the National Population Health Survey, Canadian Community Health Survey, Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada, and linked health services, morbidity and mortality, and landed immigrant databases. Immigrants consistently report better health and health characteristics upon arrival than the general Canadian-born population; however, this health advantage diminishes over time, and certain immigrant populations are at increased risk for decline in health status and for poorer health outcomes.

Most new migrants are healthy

Most (> 90%) migrants arriving in Canada report very good to excellent health10,11,15,16,21,22,26 and display health characteristics that equal or exceed those of Canadian residents.7,15 This observation is known as the healthy immigrant effect and has been the subject of frequent study.6,43 Several reasons for this finding have been suggested, including differences in the socio-cultural aspects of diet, activity, nutrition and the use of tobacco and alcohol that exist between the migrants’ place of origin and Canada. Further, Canadian immigration policies that can deny admission to those with certain health conditions could contribute to greater overall health at arrival.44

After migration, several of these beneficial health indicators become less pronounced with increased duration of residence.22,44 Age-standardized all-cause mortality is lower for immigrant and refugee populations than for the Canadian-born population (standardized mortality ratio 0.34–0.58);14 however, subgroups of immigrants are at increased risk of mortality23 from stroke (odds ratio [OR] 1.46, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00–1.91 Southeast Asia), diabetes (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.03–2.32 Caribbean) and infectious disease (AIDS OR 4.23, 95% CI 2.72–5.74 Caribbean) and liver cancer (OR 4.89, 95% CI 3.29–6.49 men).14 Further, McDonald and Kennedy report that the incidence of type 2 diabetes increases among nonrecent immigrants when examining two periods of cross-sectional data.15 Other illnesses, mental illnesses13 and arthritis25 are less common in immigrant populations.

Illness and disease are inequitably distributed

Canadian literature on health transitions among immigrants suggests that, over time, refugees (OR 2.31),22 low-income immigrants (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.3–1.7) and recent non-European immigrants (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.6–3.3) have an increased risk of transitioning to poorer health.10 More detailed research is required to better understand the pathways that lead to this decline in health.

For illnesses and diseases that have a low or very low prevalence in Canada, migrants originating from regions of the world where these diseases are widespread can be at increased risk of disease.45 This is often seen in regard to infectious diseases that continue to be common in developing countries.14,46 The risk of infectious disease in some migrant populations continues after arrival, as those who make return visits to their homeland might re-expose themselves and their children to threats not present in Canada. Migrants travelling to visit friends and relatives47 are an increasingly important aspect of modern travel medicine.48

Differing prevalence rates can also be seen for diseases that are genetically or biologically determined or those that occur more commonly abroad. Examples include inherited disorders such as the hemoglobinopathies, ethnic differences in the progression and natural history of cardiovascular and endocrine disease, and regional differences in the epidemiology of malignancies.49 Studies also suggest that rates of cancer differ from rates in the Canadian-born population and those in the source countries. Of particular concern are increased rates of stomach, nasopharyngeal and liver cancers that persist after migration and rates of prostate and breast cancer that increase after migration in some populations.43 Limited access to care at their place of origin can create a situation where migrants present with illnesses in later or more advanced stages than usually encountered in Canada. This is often seen in migrants from poorly developed economic areas or communities where socio-economic limitations to the access and use of health care services have existed.3,19,20,22

Economic deprivation and poverty are more common in refugee and humanitarian populations, such as refugee claimants and the involuntarily displaced, and they can further exacerbate adverse health outcomes produced by violence, trauma and torture.24,50–52 Finally, the stresses and pressures of immigration have been associated with depression and psychosocial illness, particularly in such vulnerable populations as the elderly or refugees.53,54 Limited ability to speak English or French is also associated with reporting poor health (OR 2, 95% CI 1.5–2.7).26

Clinical considerations

Is access to health services an issue for migrants?

New immigrants are twice as likely to have difficulties in accessing immediate care as those born in Canada.55 However, when linguistic needs of migrants are considered in multidisciplinary service environments, differences in care between migrants and other Canadians can be reduced for specific conditions.56

Language barriers to accessing health care and health promotion services exist for immigrants to Canada. Large numbers of newly arriving migrants are neither literate nor conversant in either of the two official languages in Canada (English and French). In 2005, 36% of new arrivals (just over 94 000 people) stated that they had no knowledge of either language on arrival in Canada.57 This language barrier reduces the utility and relevance of prevention or health promotion information prepared in English or French and can complicate surveys and data gathering. The linguistic and cultural needs of many immigrant communities have been recognized by health practitioners working with new immigrants, and the amount of health information available in different languages and alternative media has grown. There are potential difficulties in access and use of prevention and promotion services (v. treatment and management), as immigrants themselves might not see these services as an immediate priority.20,22

Even once health care is accessed, society and cultural dimensions exert important influences on the understanding, recognition and management of health risks and disease in such diverse populations as migrants. Immigrants can originate from areas of the world where concepts of health care and health care delivery differ from the traditional Western allopathic system of medicine. Some of these concepts (such as metaphysical imbalances common in some Asian populations58 or belief in illness resulting from hostile spirits or curses59) can be challenging for providers unfamiliar with them.60–63 Further, cultural beliefs can influence the selection of treatment or the acceptance of preventive care, such as screening. Examples include migration-related differences in selection and use of providers,64 use of medication,65 joint replacement66 and cervical cancer screening.4,19

What are the implications for health services and for disease prevention?

As long as global health inequities continue to exist, large-scale immigration can bring the clinical consequences of different epidemiologic environments to the migrants’ new home. As a consequence, health services and disease prevention and management strategies require a broader, more international perspective. The aggregation of immigrants in a few provinces and cities means that most migrant-associated health and medical demands will be primarily encountered in urban practice environments. Practitioners in situations involving small numbers or groups at increased risk such as refugees or refugee claimants can benefit from standardized guidelines and recommendations derived from aggregate or collaborative studies. Community and public health initiatives involving nationally coordinated, multiple centres and standardized definitions can provide improved understanding of migration-associated health issues and reduce cohort effects. For example, in Canada, country of birth is recorded for tuberculosis surveillance, providing insight on the long-term influence of migration on tuberculosis in Canada.67

The diversity and differences in health determinants, migration experiences, language and culture among migrant patients can be demanding for providers.68 Creating centres of experience or specialization in migrant health might better meet those demands.69 Once practitioners are linked via modern communications technology to others in the field, awareness of issues and clinical and research elements can be extended nationally and internationally to maximize both knowledge and tools.

Evidence also indicates the importance of projects and programs that directly involve members of migrant communities.70 This can be particularly important in situations where populations are marginalized or encounter barriers that limit their use of mainstream health care services.71 New immigrants can receive important support in navigating these situations from existing migrant communities and family members who have arrived in Canada earlier.72,73

Conclusion and research needs

Immigrants and refugees represent heterogeneous populations that offer both unique challenges in the provision of health services and opportunities for prevention and early detection of illness. Understanding the selection and screening processes involved in immigration, the demographics of immigrants and refugees to Canada, and the reasons for changes in health status after arrival can help practitioners tailor health promotion and preventive care services. The delivery of primary care for culturally diverse populations with a range of settlement needs must also encompass social determinants of health, not simply the presence of disease in migrant populations. Research is needed to improve the responsiveness of primary care for immigrant populations.

Key points

International migration reduces the effects of distance and results in rapid links between epidemiologic disparities that have implications for preventive care.

Some migrant populations have health needs that reflect their place of origin and experiences that differ from Canadian-born patients.

Better appreciation of the nature and source of these disparate health parameters can reduce diagnostic delay and lead to culturally and linguistically appropriate health services.

Clinical preventive guidelines for newly arrived immigrants and refugees to Canada

This article is part of a series of guidelines for primary care practitioners who work with immigrants and refugees. The series was developed by the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the support of Sarah McDermott from the Public Health Agency of Canada in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Brian Gushulak is a consultant with Migration Health Consultants, Inc.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Brian Gushulak, Janet Hatcher Roberts and Sara Torres were involved in the conceptual design and the preparation of the manuscript. Kevin Pottie and Marie DesMeules were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the literature review. All authors provided intellectual content and reviewed, edited and amended the manuscript during its submission and acceptance. All authors reviewed and approved the initial submission and the final version submitted for publication.

Funding: The Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health acknowledges the funding support of the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Institute of Health Services and Policy Research), the Champlain Local Health Integrated Network and the Calgary Refugee Program. The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and neither necessarily reflect nor represent the position of any government department, agency, university or professional society to which the authors belong.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Organization of Migration The world migration report. Geneva (Switzerland): The Organization; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health Agency of Canada What determines health? Determinants of health, key determinants, research and evidence base, health status indicators. Ottawa (ON): The Agency; 2010. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/determinants/index-eng.php (accessed 2008 Oct. 2). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson R, Marmot M. Social determinants of health: the solid facts. 2nd ed Copenhagen (Denmark): World Health Organization; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacPherson DW, Gushulak BD, Macdonald L. Health and foreign policy: influences of migration and population mobility. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:200–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Z, Schimmele CM. Racial/ethnic variation in functional and self-reported health. Am J Public Health 2005;95:710–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyman I. Immigration and health: reviewing evidence of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. CERIS working paper no. 55. Toronto (ON): Joint Centre of Excellence for Research on Immigration and Settlement; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newbold KB, Danforth J. Health status and Canada’s immigrant population. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1981–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gushulak BD, MacPherson DW. Migration medicine and health: principles and practice. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of CareReview Group (EPOC) Data collection checklist. Cochrane Collaboration; 2002; Available: http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/datacollectionchecklist.pdf (accessed 2010 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng E, Wilkins R, Gendron F, et al. Dynamics of immigrants’ health in Canada: evidence from the National Population Health Survey. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2005. Cat. no. 82-618-MWE2005002. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-618-m/2005002/pdf/4193621-eng.pdf (accessed 2010 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez CE. Health status and health behaviour among immigrants. Health Rep 2002;13(Suppl):1–13 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trovato F. Migration and survival: the mortality experience of immigrants in Canada [research report]. Edmonton (AB): Prairie Centre for Research on Immigration and Integration (PCRII); 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali J. Mental health of Canada’s immigrants. Health Rep 2002;13(Suppl):1–11 [Google Scholar]

- 14.DesMeules M, Gold J, McDermott S, et al. Disparities in mortality patterns among Canadian immigrants and refugees, 1980–1998: results of a national cohort study. J Immigr Health 2005;7:221–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Insights into the ‘healthy immigrant effect’: health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1613–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newbold KB. Self-rated health within the Canadian immigrant population: risk and the healthy immigrant effect. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:1359–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newbold KB. Health status and health care of immigrants in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vissandjee B, DesMeules M, Cao Z, et al. Integrating ethnicity and immigration as determinants of Canadian women’s health. Women’s health surveillance report. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woltman KJ, Newbold KB. Immigrant women and cervical cancer screening uptake: a multilevel analysis. Can J Public Health 2007;98:470–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Cervical cancer screening by immigrant and minority women in Canada. J Immigr Minor Health 2007;9:323–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newbold KB. The short-term health of Canada’s new immigrant arrivals: evidence from LSIC. Ethn Health 2009;14:315–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newbold KB. Health care use and the Canadian immigrant population. Int J Health Serv 2009;39:545–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, Mustar C, et al. The Canadian census mortality follow-up study, 1991 through 2001. Health Rep 2008;19:25–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis S, Setia MS, Quesnel-Vallee A. Socio-geographic mobility and health status: a longitudinal analysis using the National Population Health Survey of Canada. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:1845–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canizares M, Power JD, Perruccio AV, et al. Association of regional racial/cultural context and socioeconomic status with arthritis in the population: a multilevel analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:399–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pottie K, Ng E, Spitzer D, et al. Language proficiency, gender and self-reported health: an analysis of the first two waves of the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada. Can J Public Health 2008;99:505–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Facts and figures 2007. Ottawa (ON): Citizenship and Immigration Canada; 2008. Cat. no. Ci1-8/2007E-PDF [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visiting Canada. Ottawa (ON): Citizenship and Immigration Canada; 2007. Available: www.cic.gc,ca/english/visit/index.asp (accessed 2010 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reitz JG. Closing the gaps between skilled immigration and Canadian labour markets: emerging policy issues and priorities. Toronto (ON): University of Toronto; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Department of Homeland Security Yearbook of immigration statistics, 2008. Washington (DC): US Office of Immigration Statistics; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship Immigration update 2006–2007. Belconnen (Australia): Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Travel and tourism. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2008. Available: www41.statcan.gc.ca/2008/4007/ceb4007_000-eng.htm (accessed 2010 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahonen EQ, Benavides FG, Benach J. Immigrant populations, work and health — a systematic literature review. Scand J Work Environ Health 2007;33:96–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caulford P, Vali Y. Providing health care to medically uninsured immigrants and refugees. CMAJ 2006;174:1253–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magalhaes L, Carrasco C, Gastaldo D. Undocumented migrants in Canada: a scope literature review on health, access to services, and working conditions. J Immigr Minor Health 2010;12:132–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Immigration and Refugee Protection Act Statutes of Canada 2001, C27 Ottawa (ON) Available: http://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/I-2.5/20100421/page-0.html?rp2=HOME&rp3=SI&rp4=all&rp5=Immigration&rp9=cs&rp10=L&rp13=50#idhit1 (accessed 2010 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Citizenship and Immigration Canada Handbook for designated medical practitioners. Ottawa (ON): Health Management Branch; 2009. Available: www.cic.gc.ca/english//pdf/pub/dmp-handbook2009.pdf (accessed 2010 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Statistics Canada Portrait of the Canadian population in 2006, 2006 census. Ottawa (ON): Ministry of Industry; 2007. Report No. 97-550-XIE [Google Scholar]

- 39.The people of Australia. Statistics from the 2006 Census Department. Belconnen (Australia): Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Migration Policy Institute Frequently requested statistics on immigrants in the United States. Washington (DC): The Institute; 2007. Available: www.migra-tioninformation.org/feature/display.cfm?ID=649#1 (accessed 2009 Sept. 2). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carter T, Vachon M, Bile J, et al. L’immigration et la diversité dans les villes canadiennes — un sujet d’actualité. Rev Can Recherche Urbaine 2006;1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Statistics Canada Census snapshot — immigration in Canada: a portrait of the foreign-born population, 2006 census. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2008. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-008-x/2008001/article/10556-eng.pdf (accessed 2010 May 31). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortiz L. New Canadians for healthy living: a culturally responsive approach to chronic disease prevention. A funding proposal for the Population Health Fund, by Multicultural Health Brokers’ Co-op. Edmonton (AB): Multicultural Health Services Society; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keane VP, Gushulak BD. The medical assessment of migrants: current limitations and future potential. Int Migr 2001;39:29–42 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stauffer WM, Rothenberger M. Hearing hoofbeats, thinking zebras: five diseases common among refugees that Minnesota physicians need to know about. Minn Med 2007;90:42–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnston B, Conly J. The changing face of Canadian immigration: implications for infectious diseases. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2008;19:270–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, et al. Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:1185–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Angell SY, Cetron MS. Health disparities among travelers visiting friends and relatives abroad. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beiser M, How F, Hyman I, et al. Poverty, family process, and the mental health of immigrant children in Canada. Am J Public Health 2002;92:220–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DesMeules M, Gold J, Kazanjian A, et al. New approaches to immigrant health assessment. Can J Public Health 2004;95:122–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rasmussen A, Smith H, Keller AS. Factor structure of PTSD symptoms among West and Central African refugees. J Trauma Stress 2007;20:271–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Ryder A, et al. Depression: evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. CMAJ. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet 2005;365: 1309–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuo BC, Chong V, Joseph J. Depression and its psychosocial correlates among older Asian immigrants in North America: a critical review of two decades’ research. J Aging Health 2008;20:615–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.San Martin C, Ross N. Experiencing difficulties accessing first-contact health services in Canada. Healthc Policy 2006;1:103–19 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giordano C, Druyts EF, Garber G, et al. Evaluation of immigration status, race and language barriers on chronic hepatitis C virus infection management and treatment outcomes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;21:963–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.2005 immigration overview. In: The Monitor. 2006; issue 2: p 2–17 Ottawa (ON): Citizenship and Immigration Canada; 2006. Archived copy available: www.collect-ionscanada.gc.ca/webarchives/20071124201820/ (accessed 2010 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wiseman N. Concerning the use of Western medical terms to represent traditional Chinese medical concepts. Chin J Integr Med 2006;12:225–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.DeBellonia RR, Marcus S, Shih R, et al. Curanderismo: consequences of folk medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care 2008;24:228–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohmans P, Garrett C, Treichel C. Cultural barriers to health care for refugees and immigrants. Providers’ perceptions. Minn Med 1996;79:26–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bhui K, Craig T, Mohamud S, et al. Mental disorders among Somali refugees. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:400–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Donnelly TT, McKellin W. Keeping healthy! Whose responsibility is it anyway? Vietnamese Canadian women and their healthcare providers’ perspectives. Nurs Inq 2007;14:2–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Juckett G. Cross-cultural medicine. Am Fam Physician 2005;72:2267–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang L, Rosenberg M, Lo L. Ethnicity and utilization of family physicians: a case study of Mainland Chinese immigrants in Toronto, Canada. Soc Sci Med 2008;67: 1410–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lai D, Chappell N. Use of traditional Chinese medicine by older Chinese immigrants in Canada. Fam Pract 2007;24:56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Y, Simpson J, Wluka A, et al. Reduced rates of primary joint replacement for osteoarthritis in Italian and Greek migrants to Australia: the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Public Health Agency of Canada Tuberculosis in Canada 2006. Ottawa (ON): Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2008. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/2009/tbcan06/pdf/tbcan2006-eng.pdf (accessed 2009 Sept. 3). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pottie K, Topp P, Kilbertus F. Case report: profound anemia: chronic disease detection and global health disparities. Can Fam Physician 2006;52:335–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Consortium on Health and Mobility Minneapolis (Minn): Consortium on Health and Mobility; 2009. Available: http://healthandmobility.org/Health_and_Mobility/Welcome.html (accessed 2010 Apr. 21).

- 70.Nerad S, Janczur A. Primary health care with immigrant and refugee populations: issues and challenges. Aust J Prim Health Interchange 2000;6:222–9 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Healthy women — healthy communities project. Toronto (ON): Comunidad Sana/Healthy Women Healthy Communities; 2003. Available: www.mujersana.ca/msproject/framework3-e.php#a (accessed 2008 Oct. 1). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kobayashi KM. Immigration, ethnicity and health. In: Bolaria BS, Dickenson H, editors. Health, illness, and health care in Canada. 4th ed Scarborough (ON): Thomson Nelson; 2008. p. 204–19 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pitkin Derose K, Bahney BW, Lurie N, et al. Review: immigrants and health care access, quality, and cost. Med Care Res Rev 2009;66:355–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.