Abstract

The development of therapeutic approaches to treat lung disease requires an understanding of both the normal and disease physiology of the lung. Although traditional experimental approaches only address either organ or cellular physiology, the use of lung slice preparations provides a unique approach to investigate integrated physiology that links the cellular and organ responses. Living lung slices are robust and can be prepared from a variety of species, including humans, and they retain many aspects of the cellular and structural organization of the lung. Functional portions of intrapulmonary airways, arterioles and veins are present within the alveoli parenchyma. The dynamics of macroscopic changes of contraction and relaxation associated with the airways and vessels are readily observed with conventional low-magnification microscopy. The microscopic changes associated with cellular events, that determine the macroscopic responses, can be observed with confocal or two-photon microscopy. To investigate disease processes, lung slices can either be prepared from animal models of disease or animals exposed to disease invoking conditions. Alternatively, the lung slices themselves can be experimentally manipulated. Because of the ability to observe changes in cell physiology and how these responses manifest themselves at the level of the organ, lung slices have become a standard tool for the investigation of lung disease.

Keywords: precision-cut lung slices (PCLS), airways, arterioles, blood vessels, alveoli, epithelium, cilia, smooth muscle cells, calcium, asthma, COPD, β2-adrenergic agonists, 2-photon microscopy

1. Introduction

The primary objective of lung disease research is the identification of molecular events at the cellular level that manifest themselves at the organ level as physiological changes that impair airway, vessel or lung function. This goal has been traditionally approached in several ways; studies of organ physiology have sort to document changes, at the whole lung level, by examining physical parameters such as airway resistance or lung compliance in response to a variety of stimuli. For example, airway resistance can be calculated from pressure changes associated with the inflation of the lungs with randomized volumes in response to aerosols of acetylcholine (ACh). Similarly, perfused lung preparations can be used to evaluate changes in pulmonary circulation in response to stimuli such as hypoxia or circulating agonists. While these techniques are vital to correlate large scale physiological behaviors, their macroscopic characteristics hinder the assessment of the microscopic processes involved. Consequently, an alternative approach has been the use of isolated tissue strips or cells. Tissue strips from upper airways have been extensively used for the investigation of smooth muscle force generation. For technical reasons, an averaged tissue force is perhaps the only way to obtain data reflecting force generation by the component cells. However, related individual cell processes remain inaccessible. As a result, isolated cells are required. Commonly, such cells are of a single type, maintained in culture and maybe immortalized. The advantages of cultured cells for biochemical and genetic analysis or experimental manipulation have long been appreciated and a wealth of data has been accumulated. On the other hand, these isolated cells now lack many of their characteristic associated with tissues in organs; the cells are near identical, grow on foreign substrates without normal extracellular matrix, lack cell communication with other cell types and have little resemblance to normal tissue organization. As a result, the extrapolation of how cellular events precisely determine physiological events at the level of the organ is frequently speculative.

One solution to the conundrum of experimentally coupling molecular and organ scales is the intermediary preparation of a living lung slice. An ideal representative lung slice consists of a relatively thin segment of the lung and contains alveoli tissue with imbedded intrapulmonary airways and blood vessels; the morphological organization of the various cell types in these lung slices is near identical to the lung in vivo. Perhaps more importantly, the individual cells within the lung slice are accessible for study while the physiological responses (e.g. contraction) of airways and blood vessels are retained. Although there are alternative ways to examine airway dynamics with whole airway segments, the cell responses are not accessible [1]. From our own work, investigating airway constriction relevant to asthma, the relationship between cellular activity and changes in airway size is exemplified by the ability to monitor agonist-induced Ca2+ changes and the associated contraction of airway smooth muscle cells (SMCs).

The concept of using tissue slices has been appreciated for some time and this technique has been extensively used for metabolic studies and toxicology assays where the mean activity of the lung slice, rather than that of individual cells, is the focus of the study. Liberati et al., [2] have comprehensively reviewed many of these earlier uses of slices, as well as more recent applications. Rather than reiterate a survey of the varied applications for lung slices, the objective of this review is to address the implementation of the lung slice technique and its use for the study of lung physiology and disease.

2. Lung slice preparation

The original focus on organ metabolism required that all cell types and their potential interactions were part of the experiment and early approaches utilized liver slices. Such slices were often cut “by hand” without additional support and were relatively thick (1 to several millimeters). However, a common concern with thick slices, especially those with high cell densities, is that of necrosis and apoptosis of the central tissue due to limited nutrient diffusion. As a result, cell viability assays were essential to verify slice health. For metabolic studies, the variability in thickness of “hand cut” tissue slices was also a potential source of error in comparative studies. Consequently, the slice technique was partially standardized by the use of quantifiable slicing tools that produced slices which only varied in thickness by approximately 5% [3–5]. This gave rise to the name precision-cut tissue slices. The early extension of the slice technique to lung tissue still produced slices with very variable thickness as a result of the soft and pliable nature of lung tissue [6]. However, a major step towards obtaining lung slices with a more consistent thickness was achieved by inflating the lungs with agarose [7]. Subsequently, relatively thick (0.5 mm) agarose-filled lung slices were used to study airway contractility [8]. The final advance came with the application of mechanical slicing by Martin et al., [9] to produce precision-cut lung slices (PCLS) from rats approximately 250 μm thick. Agarose-filled lung slices have now been prepared from mice [10, 11], guinea pigs [12], monkeys [13], horses [14] and humans [15]. With these advances, as Liberati et al. [2] points out, the use of lung slices has now been widely adopted.

a) Lung inflation with agarose

While the basic approach for the preparation of lung slices is relatively straightforward, the details often vary with the laboratory. Commonly, lungs are inflated with warm (37°C), saline-equilibrated agarose which is subsequently cooled to stiffen the lung tissue for slicing. Low-melting point agarose is used because the temperature of the agarose solution must be reduced to body temperature without gelling. However, agarose gelling will occur at ~25 to 30°C (depending on type), consequently, the lung tissue should be kept warm (e.g. heat lamps) during inflation to ensure that premature gelling does not occur in the upper airways and prevent the even distribution of the agarose into deeper parts of the lung. However, the name “low-melting point agarose” appears to have led, in some cases, to the misunderstanding that once the lung slices are placed in culture medium at 37°C, the agarose re-melts and is removed. The transparency of agarose during microscopic examination contributes to the impression that agarose is absent. However, careful examination of the alveolar tissue, especially with phase-contrast optics, will often reveal a series of parallel score-marks left by the vibrating cutting blade. The melting point refers to the transition of the agarose, from gel to fluid when reheated; this occurs at ~65°C for low-melting point agarose and ~87°C for standard agarose. At 37°C, the agarose remains as a gel in the alveolar tissue. In fact, this is essential because the agarose provides a positive alveolar pressure (equivalent to negative pleural pressure) to maintain the inflated state of the slice. Without the agarose, the lung slice would collapse. However, for studies of airway contraction or ciliary activity in which agarose may offer resistance to contraction or interfere with ciliary movement, it is desirable to prevent the agarose from gelling in the airways. This can be achieved by following the agarose injection with a bolus of air, to flush the agarose deeper into the alveolar tissue. In larger main bronchi, it is also possible to dislodge by washing, or physically removing the agarose plugs from the airways.

Important points to consider when inflating the lungs are the inflation pressure and liquid volumes used. Lung tissue is highly compliant and easily damaged. Because agarose is often injected with a syringe, care should be taken to minimize the injection pressure, and it should be appreciated that the agarose has a significant viscosity (as compared to air) and will have a delayed inflation time. The volume of agarose used is dependent on lung size which varies with species and age (i.e. body size). Ideally, the inflation volume (including any subsequent air bolus) should not be greater than total lung capacity (TLC); greater volumes are likely to result in baro-trauma. In most cases it is probably better to inflate to a volume lower than TLC but greater than functional residue capacity. This provides sufficient lung stiffness for slicing while lessening the chances of stretch-induced damage.

Agarose gelling is usually initiated by the application of cold saline (4°C) to the lungs. The time taken to gel varies based on injection volumes, but the end-point is easily assayed. However, during the early phase of cooling and until the agarose has sufficiently stiffened, it is important that the pressure used to inject the agarose is maintained, otherwise the lung recoil forces will drive the liquid agarose out of the alveoli into the airways and reduce the lung volume.

The next step involves cutting the lung slices. The most popular instrument employed to obtain slices of comparable thickness has been the Krumdieck tissue slicer (Alabama Research and Development) [5]. Because of cost, we and others have used an alternative slicer, the EMS 4000 (various companies) and obtained excellent slices [11, 14, 16]. However, more recently, we have preferred the VF-300 microtome (Precisionary Instruments). The major advantage of the VF-300 and Krumdieck slicer with respect to the EMS 4000 is that the lung tissue is held within an agarose-filled cylinder; the agarose-filled (or surrounded) tissue is incrementally advanced for slicing. This design prevents distortion of the tissue by the cutting blade during blade advance and produces better slices at lower agarose concentrations (less than 2%).

b) Route of agarose instillation

The most common and easiest way to deliver the agarose to the lung is by cannulating the trachea. In bigger animals, especially with human lungs, cannulation of a bronchus is more common. However, human lung tissue is frequently obtained as a surgical resection sample and only consists of a partial lobe. When possible, it is best to use a distal apex of a lobe, with an undamaged visceral membrane. Here, the distal portions of the airways remain intact and terminate in alveoli. By cannulating multiple small airways on the cut surface of the lobe, the lung tissue can be inflated in several steps [17]. If the airways are rendered open-ended by dissection, inflation of the tissue is very difficult because of agarose leakage. In the event of difficulty in finding airways, multiple small injections of 3% agarose directly into the alveoli tissue with a fine gauge needle has been reported to inflate lung tissue [18].

c) Lung slice location and orientation

With respect to understanding SMC activity, related either to asthma or hypoxia, earlier studies focused on the behavior of strips of tracheal muscle or external pulmonary vessels with wire myographs. However, SMCs from these locations may not represent intrapulmonary airways and blood vessels. In this respect, the lung slice technique provides the necessary access to the small airways and blood vessels of the lung. However, within the lung, these airways and vessels can vary considerably in size and structure with position and this has been found to have an effect on airway responses. In rat lungs, the smaller airways are often more responsive than larger airways [9, 19, 20]. The sequential nature of sectioning provides the ability to collect serial lung slices and study how airway or vessel physiology is modulated along the bronchial tree [21]. In mouse airways, the distal and proximal airway SMCs displayed less contraction and slower Ca2+ oscillations than intermediate sized airways [21]. While this appears slightly different to rat airways, this difference raises the problem of comparing airway size between species. Equal sized airways from rats and mice represent different airway generations, whereas equal airway generations will have different sizes and associated structures. At least within one species, it is best to use similar sized airways for comparative experiments. Commonly, the largest airways or blood vessels are studied as these dominate the lung slice [12, 19, 22], but these are similar to the extra-pulmonary airways and blood vessels. The lung slice is best used for the small-sized airways and arterioles [23–25].

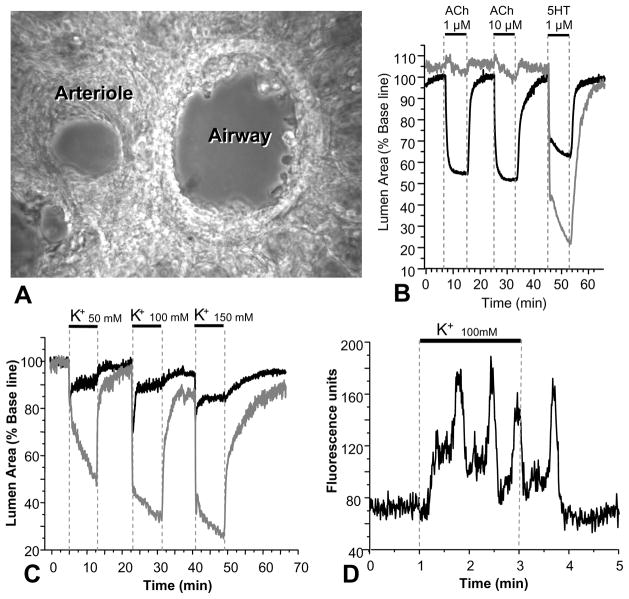

A lung slice containing airways and blood vessels in transverse section has the advantage that adjacent airways and arterioles are readily observed (Fig. 1A). This has the added benefit that comparisons of airway and arteriole physiology can be monitored simultaneously [16, 23]. We have found this to be extremely valuable for understanding SMC signaling. Frequently, one SMC type would serve as the control for the other SMC type. For example, in mouse lung slices, ACh only contracts airway SMCs whereas 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) contracts both airway and arteriole SMCs (Fig 1B). On the other hand, KCl induced sustained contraction in arteriole SMCs but twitchy contraction in airway SMCs (Fig. 1C). These contrasting results were extremely useful to understand and confirm different regulatory mechanisms of contraction and relaxation in different types of SMCs.

Figure 1.

The appearance and responses of an airway and arteriole in a mouse lung slice. (A) A phase-contrast image of a lung slice showing an airway (right) and associated arteriole (left), in transverse section, surrounded by alveoli. (B) The contractile responses of an airway and arteriole to acetylcholine (ACh) and 5-hydroxytrytamine (5HT). The airway, but not the arteriole contract in response to ACh; both airway and arteriole contract to 5HT. (C) The responses of the airway and arteriole in (A) to increasing concentrations of K+; the airway shows a weak response as a result of uncoordinated twitchy SMC contractions, where as the arteriole shows a sustained contraction. (D) Slow Ca2+ oscillations induced by K+ in arteriole SMCs. K+ initiates a slow increase in Ca2+ before the first Ca2+ spike. Similar Ca2+ oscillations are observed in airway SMCs in response to K+. The greater contraction of the arteriole as compared to the airway in response to these slow Ca2+ oscillations is believed to be the result of greater Ca2+ sensitivity in the arteriole SMCs. Data by J. Perez-Zoghbi.

However, transverse sections of blood vessels may not be ideal. The airways are lined with cuboidal epithelial cells, and an airway within a lung slice that is several hundred microns thick has multiple epithelial cells between the two cut edges. However, blood vessels are lined by long, thin endothelial cells that run parallel to the length of the vessel. Hence, in thin transverse sections, these cells are likely to be damaged and this may influence blood vessel responses. Therefore, for the study of blood vessels, it is recommended that lung slices are cut parallel to the longitudinal axis of blood vessels. In this way, a portion of the blood vessel may remain intact across the lung slice. With this orientation, the lumen of the vessels is more difficult to observe with conventional light microscopy but two-photon or confocal microscopy can easily image structures that are placed nearer the middle of a slice. The activity of the endothelial cells relative to the SMCs can also be addressed. Longitudinal slices of airways would also be better for the visualization of the profile of ciliary activity near the cut edges of airways, while a top view of the airway wall would facilitate the observation of ciliary metachrony.

d) Lung slice artifacts and problems

Although the aim of simultaneously examining airway and arteriole physiology is very attractive, the preparation of lung slices that conserve arteriole morphology is more challenging. In addition to the potential problems of slice orientation mentioned above, arterioles frequently display a strong irreversible contractile response during slice preparation. It is common to observe the walls of the blood vessels in a shriveled state within a large hole surrounded by sparse connective threads. This morphology is observable in many published papers but usually elicits little comment and appears to be accepted as normal. We have been partially successful in overcoming this artifact by filling the blood vessel lumen with gelatin [23]. This process is similar to the inflation of the lung parenchyma with warm agarose, except that warm gelatin at 6% is used to perfuse the blood vessels via the heart and the pulmonary artery. Gelatin was used because this does dissolve upon warming to 37°C. With this approach, we have preserved intact arterioles that undergo significant contraction and relaxation (Fig. 1). Although artifactually contracted arterioles appear as if they have ripped themselves away from the lung parenchyma during slice preparation, we have never been able to experimentally induce a strong contractile response like this in well-persevered arterioles. This suggests the agarose filling or cutting process stimulates extremely strong vascular contraction. Another factor that might contribute to the tendency of the blood vessels to separate from the lung parenchyma is their embryonic development; airways and parenchymal tissue develop from the same origin (ectoderm), whereas blood vessels have a mesodermal origin and therefore may not be as strongly connected to the surrounding tissue. Agarose appears to fill the space surrounding the blood vessels and this will prevent any subsequent arteriole relaxation. It is worth noting that mouse airways have never been observed to display this contractile behavior – thus, airway and arteriole SMCs have fundamental physiological differences. A full understanding and solution to this problem would be extremely valuable.

A similar phenomenon is also found with airway SMCs in some other species, primarily guinea-pig lung slices [12] although human lungs slices have a variable, but comparable response [12, 17]. Airways of these species are frequently contracted following slicing. However, the airway remains connected to the surrounding parenchyma. Again, this response is not well understood, although airway relaxation can be partially or completely regained by either prolonged washes with buffer or the inclusion of airway relaxants or antagonists of contractile agonists [12, 15]. The most likely explanation for this contractile response to slicing is the release of contractile agonists and the activation of mast cells in response to cell damage or by the severing of neural nets to stimulate neuro-transmitter release. Again, a better understanding of this response would be extremely helpful in ameliorating the effect.

Although not fully investigated, the method of animal death may impact lung function and hence slice viability. We have avoided inhalation of CO2 or anesthetics due to the likelihood these will impact the lung tissue. Cervical dislocation may influence tracheal accessibility. Peritoneal injection of Nembutal appears to have minimal effect on lung tissue.

e) Lung slice stiffness

A major parameter associated with lung slice preparation that is often varied is the agarose concentration; this ranges from 0.5% to about 4% with many studies using 0.75%, 1.5% or 2%. A systematic evaluation of the affect of agarose concentration has not been addressed but the success with these variable approaches might suggest that the specifics are not critical. The most likely factor determining the required agarose concentration is the type of tissue slicer used. Those slicers that support the tissue (i.e. in an agarose-filled tube) are more likely to produce lung slices at lower agarose concentrations. The influence of the agarose stiffness will depend on the intended use of the lung slice. For metabolic or toxicological studies, in which end assays consist of homogenization of the tissue to measure changes in selected compounds, it might be expected that variation in agarose concentration would have little impact on a static lung slice. However, over-inflation could damage the lung slice and lead to unexpected trauma-based responses.

By contrast, studies of dynamic changes in tissue shape, i.e. airway or blood vessel contraction, are strongly dependent on the mechanical coupling properties of the lung tissues and this, in turn, might be influenced by the stiffness of the agarose gel within the alveoli. We have observed substantial airway contraction (up to ~60% with methacholine, MCh) and relaxation in lung slices prepared with 2% agarose. While the absolute magnitude of the contraction may differ between lung slices with different agarose concentrations, it is likely that relative magnitude of contractile responses will remain similar when compared in lung slices with the same agarose concentration. However, an interesting observation made with 2% agarose lung slices is that the stretch distortion of the surrounding airway tissue is relatively small and appears to be limited to the adjacent alveoli [26]. The more distal tissue remains relatively undisturbed during an airway contraction. The implication is that agarose in distal alveoli has relatively little influence on airway contraction, with most resistance being offered by only local alveoli and the airway wall properties.

On the other hand, lung slices prepared with 0.5% agarose may not have insufficient inherent recoil capacity to mediate airway relaxation after contraction. The placement of a Teflon retaining ring (replaced a platinum ring for electric stimulation) over the lung slice was necessary to visualize airway relaxation [27]. Presumably, the retention ring serves to anchor the more distal lung parenchyma during contraction and thereby establish the required recoil forces during contraction for relaxation. One study fixed the outer lung edges with glue [13]. We use a fine nylon mesh to hold slices in place.

The extra stiffening of the agarose coupled with higher lung volume inflation can be exploited to overcome SMC contraction when a static airway is required, as is the case, for the study of small airway ciliary activity [28]. The higher lung volume will lead to increased tethering forces and the stiffening of the airway wall. However, in view of the idea that changes in wall stiffness during contraction are localized events, the exact contribution of increased agarose stiffness to increased wall stiffness is less clear. Nevertheless, this approach keeps the airway epithelium relatively static to enable the monitoring of ciliary movements during drug application.

f) Lung slice maintenance and viability

A major reason for using lung slices is the fact that both the macroscopic and microscopic anatomy of the lung slice is near identical to in vivo tissues. Therefore the conditions in which the lung slices are maintained should preserve this state. Unlike standard tissue culture conditions, stimulation of cell growth is generally not required. Therefore, only a sustaining culture medium is used and serum is not added because it contains many growth factors. In their review, Liberati et al., [2] found that a wide variety of media types have been used, but a specific correlation between media type, atmosphere and increased viability or physiological response has not emerged.

In general, lung slice viability appears to be excellent for 1 to 3 days. Tissue thickness is a factor that influences viability, but this is less of an issue in lung slices as compared to other tissue types due to the low density of cells in the lung slice. The major approach to augment diffusive gradients is media mixing by the use of roller cultures [9]. However, we have found that simply immersing thin lung slices (150 – 250 μm thick) in medium in separate wells of multi-well dishes works well. Slice separation also has the advantage of limiting contamination. Cell viability can be monitored in numerous ways, such as live/dead dyes, lactate dehydrogenase release, mitochondrial activity or thymidine incorporation [9, 12] or by the ability of the airways and blood vessels to contract in response to physiological stimuli. While it is expected that cell death will be greatest at the slice edges due to cutting, this artifact can affect cells deeper in the slice as a result of their orientation. As mentioned earlier, endothelial cells extend across the thickness of the slice may sustain damage at their tips. Likewise airway SMCs that have a spiral orientation around the airway may also be subject to edge effects. Consequently, a compromise between cellular health, nutrient and gas diffusion, optical properties and slice thickness needs to be reached.

Lung slices can survive for longer periods (up to 7 days) but some change in physiology appears to occur. For example, we have noted airway SMCs begin to display random twitching [29]. This likely reflects Ca2+ store overloading, followed by Ca2+ release. While these changes may seem undesirable, they have not been investigated. The stimulation of cell growth in lung slices might well be an ideal way to examine cell migration or remodeling processes. Longer culturing periods may provide an approach to examine changes in extracellular matrix. For this approach, it would be essential to produce lung slices under sterile conditions. While aseptic technique is generally practiced for the preparation of short-term use of lung slices, antibiotics adequately compensate for any short-falls in technique. However, the reduced use of antibiotics would be a valuable advance but this would increase the complexity of lung slice preparation.

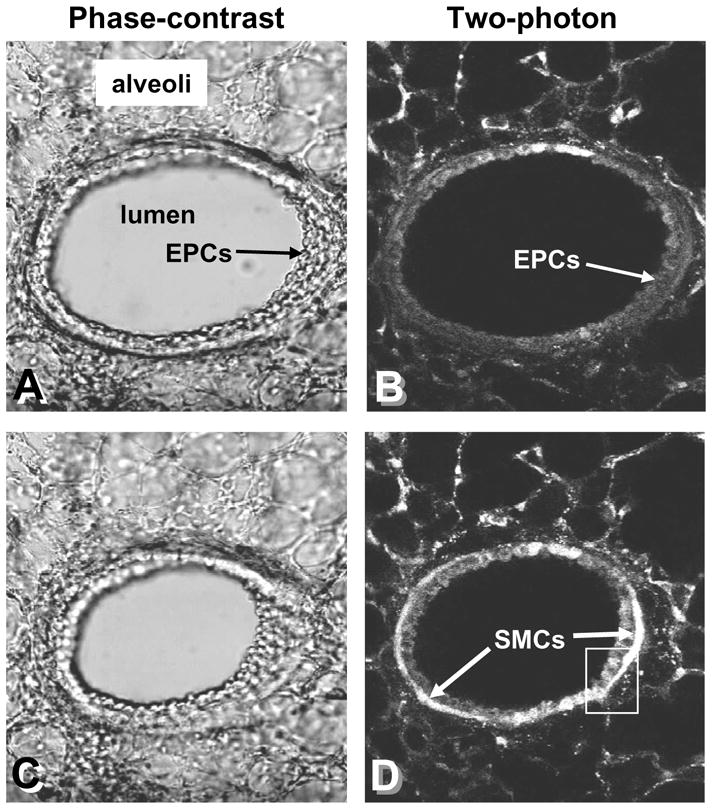

3. Visualization of lung slices

A primary approach that has emphasized the value, and hence popularized the use of lung slices, has been the implementation of various microscopy/imaging techniques which allow lung physiology to be directly observed. The principle aim underscoring this approach has been the observation of airway contraction – a fundamental response relevant to asthma. Airway relaxation is equally important, especially for asthma remedies, but because this is a passive process, it has been difficult to study in cell culture systems that lack re-coil forces. Microscopy of lung slices now provides the ability to observe multiple, consecutive contractions and relaxations of both airways and blood vessels (Figs 1 and 2).

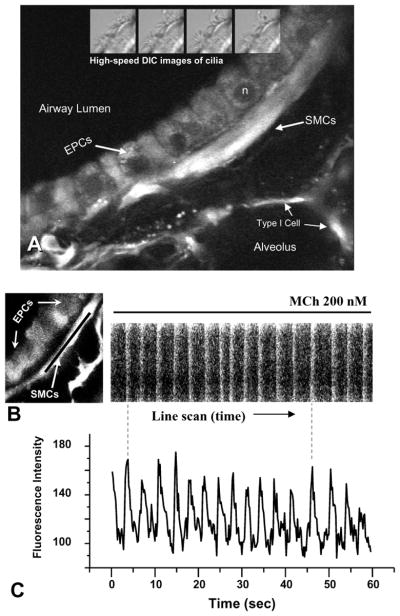

Figure 2.

Simultaneous low-magnification phase-contrast and two-photon images of a mouse airway stimulated to contract with MCh. (A and B) A relaxed airway; the epithelial cells (EPCs) line the airway lumen and are surrounded by smooth muscle cells (SMCs). (C and D) In response to MCh, the Ca2+ in the SMCs is increased, as indicated by the increased fluorescence intensity, and the airway contracts. The epithelial cells do not show a strong change in fluorescence. Inset box – see figure 3. Data by M. Edelmann.

A second major step in the observation of lung physiology has come with the advent of the advanced microscopy techniques of confocal and two-photon microscopy. These techniques provide the ability to monitor physiologically relevant messengers, such as Ca2+, or microscopic events, such as vesicle fusion, with fluorescence reporter molecules at a single optical plane within the lung slice (Figs 2 and 3). The importance of this optical sectioning is that the influence of the lung slice thickness is greatly reduced in comparison to wide-field or transmitted light microscopy techniques. An obvious extension of this ability to visualize fluorescence probes within lung slices is the exploitation of the numerous transgenic reporter dyes based on green fluorescent protein. Such dyes have a wide spectrum of uses including the detection of second messengers, targeting and tracking proteins and identifying and tracking cells. Currently, the primary limitation on these studies seems to be instrumentation availability. An extremely exciting prospect is that high-resolution (stimulated depletion, STED) microscopy [30] that has a resolution of around 50 nm may also be applied to lung slices.

Figure 3.

Ca2+ oscillation in mouse airway SMCs induced by MCh. (A) A representative two-photon image showing the organization of the airway wall; epithelial cells (EPCs) line the lumen and are surrounded by smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Alveoli spaces and cells lie adjacent to the SMCs. Ciliary activity (4 insets, top) can be viewed in lung slices with differential-interference (DIC) optics to measure ciliary activity with high-speed imaging. (B) A line scan (black line) analysis of Ca2+ changes induced in a SMC by 200 nM MCh. Each Ca2+ oscillation propagates along the cell (near vertical white line). The slight angle of the white line indicates the propagation velocity. (C) A point analysis of the same Ca2+ oscillations induced by MCh. The Ca2+ oscillates at 16 min−1 in this example. Ca2+ data by Y. Bai.

a) Microscope chamber and perfusion for lung slices

For all microscopy approaches, it is essential to mount the lung slice in a chamber with the ability to easily change the surrounding solutions without disturbing the lung slice. However, the choice of an upright or inverted microscope will predict chamber design. Chambers can be custom-made or purchased. The tendency for the lung slice to float requires that they are weighted and this can be achieved by a wire ring in an open chamber [9]. We have constructed a very simple, closed chamber from two cover-glasses that holds the slice in place for inverted microscopy [31]. This has the advantages that it is cheap and easily made from clean glass to avoid contamination.

A large cover-glass serves as the bottom of the chamber. This is supported by a Plexiglas frame. The lung slice is placed on the cover-glass with minimal fluid. Two trails of silicone grease are squeezed out parallel to the lung slice. The slice is covered with a nylon mesh with a central hole aligned over the area of interest. A second cover-glass is placed on top, so that the silicone grease forms the sidewalls of the chamber. The nylon mesh holds the lung slice close to the bottom cover-slip and serves as a spacer for fluid exchange. For perfusion, incoming fluid is dripped onto the cover-glass at one end of the chamber. Out-going fluid is removed at the other end of the chamber by a tissue-paper wick coupled to a suction manifold. The paper wick prevents the chamber from being sucked dry by decoupling the suction from the chamber when the chamber fluid recedes. Fluid exchange is driven by a gravity-fed perfusion system.

b) Time-lapse imaging of lung slices

The technique usually used to visualize airway or blood vessel contraction and relaxation is digital (video) time-lapse microscopy (Fig. 1). Lung slices are observed with phase-contrast, low-magnification optics (objectives x4 to x20). An extremely useful accessory is a zoom-lens between the camera and microscope; this allows the image of the lung slice to be matched to the size of the camera. Differential-interference contrast (DIC) optics are very useful to view details of live lung slices, especially at higher magnifications. However, to automate measurements of airway contraction, phase-contrast optics provide the necessary differential in image intensity between the tissue and the background (lumen area). A major factor limiting the viability of time-lapse phase-contrast imaging is the quality of the image which is highly dependent on lung slice thickness and tissue density. Early studies using thick slices or slices of the largest airways produced dark images with little detail, whereas the observation of smaller airways with thinner slices reveals considerably more detail to produce the best recordings. However, even with thin slices, the increased density of the connective tissue surrounding human airways results in a loss of detail. With a good difference in image intensity between the airway wall and the airway lumen (Fig. 1), it is possible to automatically track airway contraction and relaxation by monitoring the area of the airway lumen. The advantage of collecting numerous sequential images with only a short time-lapse interval (0.5 – 1 sec) is that the dynamics of events can be better quantified and evaluated.

A typical time-lapse system consists of a CCD video camera and a mechanism to capture multiple images. We use a CCD camera with a standard NTSC video output that is digitized by a computer frame grabber. Sequential images are saved to hard drive with specialized software (Video Savant, IO Industries CA). With rapidly changing technology, it is likely that this arrangement can be implemented by newer camera types and interfaces using computer memory.

Airway response to dynamic stretch

The idea that the dynamic stretch of airways, that is normally associated with breathing, is important for sustained airway relaxation [32] has only been testable in muscle strips [1, 32]. Validation of this hypothesis requires that small airways respond in a similar way as large airways. Lung slices provide access to small airways and consequently serve as a bioassay to test these ideas. Modification of the microscope chamber by replacing the bottom cover-glass with a transparent silicone sheet provides the ability to uni-axially stretch the lung slice; the lung slice is glued at its outer edges to the silicone sheet. By stretching the silicone sheet in all directions simultaneously, the lung slice is expanded in a manner mimicking inhalation. By cycling the stretch, a “breathing” lung slice can be simulated. Preliminary data with this approach suggests that this breathing motion can relax small airway contraction induced by MCh. Because the chamber is compatible with confocal imaging, further investigations at the cellular level are possible. A similar biaxial stretching of the lung tissue has also been performed by others and it was found that stretch of alveoli tissue increased Ca2+ levels [33].

Automated bioassay for drug discovery

Time-lapse imaging also provides the basics for an automated lung slice assay that could be used for therapeutic drug discovery. High numbers of lung slices are relatively easily produced with vibratome slicing technology and multi-well plates are appropriate for isolation of single lung slices and automated inspection by inverted microscopy and digital stage positioning. The proposed approach would be image analysis of airway lumen area before and after drug exposure. In a search for novel bronchodilators, lung slices showing increased airway lumen size (after constriction with MCh) would be identified for further investigation.

c) High-speed imaging of airway ciliary activity

Although time-lapse imaging is ideal for revealing slow motions, such as SMC contraction or cell-based motility, observation of beating activity of airway cilia requires high-speed imaging [34] (Fig. 3). Previously, studies of airway cilia have been performed with isolated or cultured epithelial cells from the nasal region or upper large airways (usually the trachea). In these studies, slow video-rate (30 frames per second, fps) imaging was often employed and beat frequency was observed to be in the region of 5 to 10 Hz. By contrast, the lung slice provides access to cilia of undisturbed epithelial cells in the small airways. A major point revealed by this approach was that the base-line for ciliary beat frequency was high, in the range of 20 – 25 Hz (measured with 200 fps imaging) and that this activity could not be increased by agonists such as ATP [28]. The concept proposed to explain this behavior was that in the lower airways of mouse, the cilia maintain a maximum beat frequency that provides protection by continual, rather than regulated, mucociliary clearance [28, 35]. A similar non-response of small airway cilia to agents stimulating adenylyl-cyclase was observed in rat lung slices [36]. Interestingly, ciliary beat frequency was increased by phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors that, like adenylyl cyclase, increase cAMP levels. The base-line ciliary beat frequency was slower in rats, being about 12 Hz; presumably a species-specific difference.

Because of their small and dense packing, the study of airway cilia requires higher magnifications and DIC optics. A water-immersion objective (x60, 1.2 NA) with a long working distance, is recommended [31]. Longitudinal airway sections are ideal to visualize the beat profile but beat frequency can be obtained from cross-sectional views (Fig. 3). A high image rate of 200 fps is recommended to resolve the ciliary movements [31]. This is easily attained with Video Savant software and high-speed CCD cameras and greatly reduces any possibility of aliasing due to a slow sampling rate of fast moving cilia.

d) Confocal or two-photon microscopy

The qualities that make lung slices viable bioassays, namely the intact complex organization of the lung tissue with multiple cells and minimal cell damage due to slice thickness, are the very same qualities that degrade microscope images. Increased tissue thickness and reflective surface interfaces lead to decreased image contrast and resolution as a result of the detection of out-of-focus light, especially when examining fluorescence preparations. Fortunately, this paradox can be solved for fluorescence imaging by confocal and two-photon microscopy which only detects light emitted from a single thin optical plane. Confocal microscopy achieves this goal by rejecting out-of-focus light with a pinhole detector, whereas two-photon microscopy only stimulates light emission from a single image plane. Two-photon microscopy has the added benefit of using near infra-red excitation laser light that has the ability to penetrate deeper into tissues with less dispersion than that of blue/green laser light used by confocal (one-photon) systems. Because of the advantages of confocal and two-photon microscopy, we have extensively used these techniques to examine Ca2+ signaling in airway and arteriole SMCs using fluorescence Ca2+ reporter dyes (Figs 2 and 3). However, fluorescence microscopy can be applied to a wide variety of bioassays.

Microscope design and construction

While our microscopes are custom-built, the design and methods to do this are relatively straightforward and readily available [37, 38]. The basic method of acquiring an image with these approaches is by a raster scan of the tissue with a focused spot of laser light. With conventional scan technology, image acquisition time can be relatively slow (a few images per second). However, we use resonant scan technology to obtain scan rates of 15 or 30 images per second; this improves the ease of observation and increases temporal resolution. With these microscopes, the full thickness of a lung slice can be sequentially imaged at high magnification. The collection and organization of images from multiple planes into a rotational stack by digital processing provides a 3D view of the slice.

Location and proximity of cells

Although lung slices are used as bioassays because they contain cells representative of whole lung, the pooling of secreted products or homogenization of the tissue, negates the ability to identify individual cell types, establish their location (and perhaps their movement) and to observe cell-specific responses within, and between, cells. By contrast, imaging provides the means to observe asynchronous Ca2+ oscillations in adjacent SMCs [11, 16]. Similarly, Ca2+ changes in individual epithelial cells can be corrected with ciliary activity [28]. The ability to image single cells and their interactions provides a level of sensitivity to pharmacological studies that exceeds that addressed by tissue biochemistry.

SMC membrane potential

We are interested in determining how changes in membrane potential of SMCs relates to contraction and relaxation of SMCs in response to agonists or KCl. Traditionally, these measurements would be performed by electrophysiological recording with electrodes. Although lung slices have been used to examine channel currents in alveolar cells [39, 40], this approach is generally better suited to easily accessible, single cells. Airway SMCs are deep within the lung slice, exist as syncytium of cells and have the major disadvantage of contractile movement; characteristics not compatible with electrophysiology. However, the detection of membrane potential by changes in fluorescence can circumvent most of these problems. A variety of membrane potential dyes are available [41], but additional work will be needed to verify this approach.

Extracellular matrix

In asthma, it is commonly believed that remodeling of the airway wall leads to altered airway responsiveness. However, the role of the extracellular matrix in this process is not well understood. In emphysema, a degradation of the elastin components of the extracellular matrix appears responsible for increased compliance. Consequently, lung slices were used to evaluate airway reactivity after the coupling of the airways to the alveoli tissue was degraded by treatment with elastase or collagenase [42–44]. The extent of airway contraction was increased by these approaches.

In addition to examining the airway reactivity, two-photon imaging provides a second modality called “second harmonic imaging” that might be used to explore collagen content or distribution of the extracellular matrix [45, 46]. Simplistically, during second harmonic imaging, transmitted laser light that passes through fibers or cells with a repetitive or crystal-like structure, undergoes a harmonic phase shift without absorption such that the emitted light has a wavelength exactly half of the illuminating light. For example, a typical two-photon wavelength of 800 nm would be detected as 400 nm. With this modality, collagen fibers can be detected without additional dyes. The collection of both transmitted and emitted fluorescence light provides the ability to co-image the extracellular matrix with intracellular events monitored with other fluorescence dyes.

Vesicle-based secretion events

Throughout the lung, vesicle-based secretion is central to the activity of a variety of cell types that can have a significant contribution to lung disease. For example, mast cell degranulation is important in allergic asthma, mucus secretion from goblet cells is vital for mucociliary clearance but often excessive in COPD and type II alveolar cell secretion of surfactant is essential for alveoli stability. Consequently, the ability to observe secretion events would facilitate our understanding of these processes. Individual exocytotic events can be observed with two-photon microscopy in multicellular tissues by the entrance of an extracellular dye (sulforhodamine B) into the fusing vesicle [47, 48] and this activity can be coupled with Ca2+ signaling. Isolated mast cell degranulation has also been imaged [49]. The visualization of mast cell degranulation, especially with reference to SMC activation, in lung slices would be extremely insightful with respect to airway hyperresponsiveness.

Neuro-epithelial bodies

Clusters of neuro-endocrine cells exist within the airway epithelium of many mammals and form neuro-epithelial bodies that are believed to serve as airway sensory receptors. Although histological information has been available, the physiological responses of these cells are poorly understood. However, with confocal microscopy and the dye 4-Di-2-ASP, the location of these neuro-epithelial bodies in the airway epithelium is readily identifiable [50–52]. As a result, additional dual channel confocal imaging studies with Ca2+ dyes have characterized their Ca2+ response to a variety of stimuli, such as ATP and depolarization.

4. Physiology revealed by lung slices

a) Smooth muscle contraction and Ca2+ signaling

A key feature initiating and mediating airway SMC contraction is an increase in [Ca2+]i. In contrast to older ideas that Ca2+ levels within SMCs simply increased to a high steady-state, numerous studies of isolated SMCs reported that airway SMCs display repetitive Ca2+ oscillations in response to a variety of contractile agonists [38]. However, the correlation of airway contraction with SMC Ca2+ signaling has only been possible by combining the lung slice technique with real-time confocal or two-photon microscopy [11, 16]. Agonist-induced intracellular Ca2+ changes were observed with the reporter dye Oregon Green (OG) [11, 16, 53] although other dyes, such as fluo-3 [28] and fluo-4 [54, 55] have been used. In our preliminary studies, we found that OG was better than fluo-3 or 4 for loading and observing Ca2+ changes within SMCs. However, fluo-3 was preferred for the examination of epithelial cell Ca2+ due to its better loading than OG into these cells [28].

In response to all contractile agonists examined with mouse [16, 25, 56, 57], rat [56] and human [17] lung slices, including MCh, 5HT, endothelin, histamine, leukotriene D4 and even KCl, both the airway and intrapulmonary arteriole (except with MCh) SMCs displayed Ca2+ oscillations that propagate, often from one end of the cell to the other, as a Ca2+ wave (Figs 1 – 3). These Ca2+ oscillations occur asynchronously in adjacent individual cells. Importantly, the frequency of these Ca2+ oscillations was proportional to, and increased with, agonist concentration and this, in turn, correlated with decreased lumen size (increased SMC contraction). By contrast, the magnitude of the Ca2+ oscillations over a range of frequencies was similar. The implication of these results is that the rate and form of the Ca2+ oscillations, rather than their magnitude, has a significant role in the regulation of SMC contraction [58].

Although the frequency of the Ca2+ oscillations varies with agonist concentration, the range of this variation also differs between species. In mouse, the Ca2+ oscillations are relatively fast with a frequency of ~20 to 30 min−1 in response to 1 μM ACh, MCh or 5HT [16, 56] or 10 nM endothelin [25]. In rats and humans, the Ca2+ oscillations are slower, in the order of 8 min−1 in response to 1 μM MCh or 5HT for rats [56] or histamine for humans [17]. In general, concentrations above 1 μM agonist do not induce further increases in Ca2+ oscillation frequency and our experiments are performed with low agonist concentrations of 200 to 400 nm that give mid-range frequencies of Ca2+ oscillations. However, in the few other studies that report Ca2+ oscillations in mouse lung slices, the frequency of the recorded Ca2+ oscillations is low, reaching only ~ 6 min−1 in response to 10 μM ACh [55] or ~ 4 min−1 at 100 nM ACh (higher concentrations induced a plateau response) [54]. These slow Ca2+ oscillations were also observed to occur as relatively small transients on a highly elevated Ca2+ baseline. Because our mathematical simulations of SMC Ca2+ signaling have indicated that the spatio-temporal details of the Ca2+ oscillations are very important to SMC force generation [58, 59], considerable attention should be addressed to the form of the Ca2+ oscillations reported. Due to instrument limitations, photon insensitivity is a common problem with confocal or two-photon microscopy and the lower fluorescence of fluo dyes, as compared to OG, at low Ca2+ concentrations makes cells with resting Ca2+ more difficult to detect. Compensation for these problems often takes the form of increased loading of fluorescence dyes. This has the potential for increasing the Ca2+ buffering within the cells, a condition that will slow and dampen Ca2+ transients.

Throughout this review, almost all the authors of papers cited emphasize the value of the lung slice in terms of its retention of both cell organization and responses that are believed to be highly representative of the in vivo lung. Consequently, in view of the prominent and long-lasting agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations in SMCs in lung slices, the significance and relevance of simple agonist-induced Ca2+ transients, typically recorded in cultured cells, to in vivo conditions must be carefully evaluated.

The mechanism underlying agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations in SMCs in normal lung slices from mice, rats and humans appears to be similar and utilizes G-protein coupled receptor activation of PLCβ, the production of the internal second messenger inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and the repetitive release and uptake of Ca2+ from internal stores (sarcoplasmic reticulum, SR) via the IP3 receptor (IP3R) [16, 23, 25, 56, 60] and SERCA pumps, respectively. The requirement for the entry of external Ca2+ is secondary, and occurs mainly to replace Ca2+ lost to the extracellular space, rather than to primarily drive the Ca2+ changes; Ca2+ oscillations occur in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ or in the presence of antagonists of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels [16, 23].

In airway SMCs in normal lung slices, in contrast to tracheal strips [61], a role for the ryanodine receptor (RyR) in agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations was not evident [17, 60]. However, KCl-induced Ca2+ oscillations (very slow frequency with a long duration, Figs 1 and 3), which are different to agonist-induced Ca2+ oscillations, appear to be mediated by excessive Ca2+ influx, followed by the overfilling of SR Ca2+ stores which leads to the sensitization and opening of RyRs to release Ca2+ and form a Ca2+-induced Ca2+ wave [59, 60]. More detailed reviews, including SMC Ca2+ signaling data obtained from other preparations, is presented elsewhere [38, 62].

b) Hypoxic-induced contraction of intrapulmonary blood vessels

The constriction of intrapulmonary blood vessels in response to hypoxia has the beneficial effect of diverting blood flow to better ventilated areas of lung. However, with widely distributed hypoxia, which may occur in advance lung disease, this response is detrimental leading to increased pulmonary blood pressure [63]. The mechanisms mediating this contractile response are not fully understood, in part, because intrapulmonary blood vessel SMCs have been relatively inaccessible. The culture of these SMCs or SMCs from the larger pulmonary artery has also raised problems with changes in phenotype. In view of these limitations, the study of intrapulmonary blood vessels within lung slices would appear to have great potential for understanding hypoxic-induced vasoconstriction.

Our multiple attempts to observe hypoxic vasoconstriction in mouse lung slices have been unsuccessful, even though we were able to demonstrate that the arterioles studied were responsive to 5HT, KCl and endothelin [23, 25]. Because hypoxic vasoconstriction is observed in whole perfused lungs, one conclusion is that slicing the lung has destroyed part of the reactive mechanism. Interestingly, neural-epithelial bodies have been implicated in hypoxia sensing [51] and these might require nerves to communicate with vessels. In addition, as noted earlier, without careful preparation, arterioles often show a sustained contracted state and may lack intact endothelial cells.

On the other hand, a few other studies with mouse lung slices report hypoxic vasoconstriction [24, 64, 65]. A major reason for the observation of hypoxic sensitivity in the studies by Paddenberg et al., [24] appears to be the fact that they investigated smaller, partially muscularized, intra-acinar arterioles as compared to larger branched arteries that parallel the bronchi. However, the response of the larger arteries was not addressed. This hypoxic vasoconstriction appeared to be associated with increased radical oxygen species (ROS) production. The studies by Desireddi et al., [64] appeared to use somewhat larger arteries, but these appeared to show contraction artifacts. A viral vector was used to transfect the lung slice with a redox-sensitive protein and Ca2+ changes were measured with fura-2. Although the analysis of these fluorescence reporters with live confocal imaging would have greatly enhanced the resolution of their findings, a similar conclusion, that an increase of ROS mediates Ca2+ influxes to generate vasoconstriction, was reached. In view of the debate regarding the mechanism of hypoxic vasoconstriction and the site of the SMCs displaying this action [66], an evaluation of hypoxic responses in arteries in serial sections of lung slices from a variety of species is warranted.

c) Modulation of SMC contraction by Ca2+ sensitivity

Although SMC contraction is associated with Ca2+ oscillations, studies of different SMC types (airways compared to arterioles in the same lung slice) or SMCs in lung slices from different species (mice, rat, human) demonstrate that the magnitude of contraction varies in response to Ca2+ oscillations of a similar frequency. A primary mechanism accounting for this variation is the sensitivity of the contractile filaments of the specific SMC to the stimulating Ca2+ (i.e. level of Ca2+ sensitivity). The mechanisms mediating Ca2+ sensitivity involves the inactivation of myosin light chain phosphatase, often by the activation of Rho-kinase, and are addressed elsewhere [38, 67].

To evaluate SMC Ca2+ sensitivity, it is necessary to experimentally control SMC [Ca2+]i. This can be achieved by permeabilizing cell membranes with detergents. However, a key feature of the lung slice is the retention of structural organization and treatment of a lung slice with detergents leads to disintegration. As a result, we developed an alternative approach to create Ca2+-permeambilized lung slices that exploits the cell’s own ion channels and requires exposure to caffeine and ryanodine [68]. Caffeine serves to activate and open the RyR of the SR. In this state, ryanodine can bind and inactivate the RyR in a partial open state. This leads to the emptying of Ca2+ from the SR which, in turn, activates a Ca2+ influx current (stored-operated current, SOC) [69]. The coupling of the SR Ca2+ content with Ca2+ influx is reviewed elsewhere [70]. By manipulating external Ca2+ concentrations, it is possible to regulate the SMC [Ca2+]i via SOC. Lung slices treated in this manner remain viable for hours although a prolonged absence of extracellular Ca2+ leads to cell loss [68].

With Ca2+-permeabilized lung slices, it was evident that airway SMCs from different locations had major differences in Ca2+ sensitivity [56, 68]. Surprisingly, mouse airway SMCs have a low Ca2+ sensitivity. In fact, sustained elevated [Ca2+]i renders mouse airway SMCs insensitive to Ca2+ and the airways become almost fully relaxed under these conditions [53, 60]. By contrast, the SMCs of adjacent arterioles have a higher Ca2+ sensitivity and remain contracted in response to elevated [Ca2+]i. Rat and human airway SMCs have a similar inherent Ca2+ sensitivity [17, 53].

The importance of Ca2+ sensitivity can be best appreciated upon exposure to a contractile agonist. In the case of the mouse, the relaxed Ca2+-permeabilized airways display a contractile response that equals that observed in normal airways, yet no change in the [Ca2+]i occurs during this response [25, 68]. Similarly, agonists substantially enhance the contracted state of rat and human Ca2+-permeabilized airways [17, 60, 68]. The conclusion drawn from these responses is that most contractile agonists simultaneously induce Ca2+ oscillations and increase Ca2+ sensitivity to mediate SMC contraction. This dual action explains why Ca2+ oscillations of an equal frequency coupled with the higher Ca2+ sensitivity of human or rat airways result in greater contraction than mouse airways with a low Ca2+ sensitivity. The results also suggest that rat airway SMCs may serve as better models for human studies than mouse SMCs.

Perhaps the most fundamental lesson to be learned from the observations that both Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+ sensitivity simultaneously and significantly determine SMC contraction, is that an understanding of how experimental conditions affect airway or blood vessel contraction can only be approached if all 3 parameters (contractility, Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+ sensitivity) are investigated. Lung slices originally gained popularity because they provided access for airway contractility assays. These same lung slices can now equally provide access to the underlying cellular processes and future studies will be deficient if these processes are ignored.

d) Mechanisms of airway relaxation and β2 -adrenergic agonists

The relaxation of constricted airways is the primary goal of acute asthma therapy and is commonly achieved with inhaled β2-adrenergic agonists [71]. As with most medications, improvements in efficacy and specificity for reduced dosing and side-effects are constantly sort [72]. Because airway relaxation is a passive process, mediated by the re-coil forces of the airway wall, the effectiveness of bronchodilators is difficult to assess with cultured SMCs that have little ability to alter their length because they are generally in contact with a rigid surface and lack extracellular components. By contrast, lung slices possess the requirements to asses the efficacy and cellular mechanisms of a potential bronchodilator, especially in small airways [73]. Small airway relaxation induced by isoproterenol [53, 74], albuterol [12, 74, 75], formoterol [17, 57], indacaterol [18] have all been examined in detail with mouse, rat, guinea pig and human lung slices.

A major clinical problem encountered with β-adrenergic agonists is receptor de-sensitization. This response is marked in airways of mouse lung slices in which isoproterenol only induced a transient relaxation of contracted airways and subsequent trials with isoproterenol were substantially less effective than the initial exposure [53]. The effectiveness of isoproterenol improved with increased time between exposures. Interestingly, rapid desensitization to isoproterenol does not appear to occur in human airways as judged by the sustained relaxation response after 5 minutes [74]. In contrast to isoproterenol, relatively short or repetitive exposure of mouse, rat or human airways to the short or long-lasting β2-adrenergic agonists, albuterol, formoterol and indacaterol did not induce receptor de-sensitization [18, 73]. However, prolonged exposure of human lung slices to albuterol, desensitized subsequent responses to isoproterenol [74]. Importantly, this action of albuterol was negated by expose to steroids [74], a response in line with acknowledge benefits of steroid therapy for asthma. Similar observations of the potential effects of steroids on airway reactivity were made in the early use of lung slices. In comparative studies to determine the value of steroids in culture media [8], Martin et al., [9] observed that hydrocortisone reduced airway contraction in response to MCh. Hydrocortisone also reduced airway contraction induced by allergen [20].

Although β2-adrenergic compounds are widely used therapies, our understanding of their basic mechanism of action in airway SMCs continues to develop. Because Ca2+ is the major mediator of airway contraction, the action of β2-adrenergic agonists was believed to counter Ca2+ increases. Receptor-mediated increases in cAMP were shown to close K+ channels and hyperpolarize cultured SMCs [76]; this would be expected to reduce Ca2+ influx via voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and thereby lead to relaxation. However, agonist-induced contraction of airway SMCs relies more on Ca2+ oscillations that primarily utilize internal Ca2+ stores [11, 16] and airway relaxation induced by all β2-adrenergic agonists tested correlates with a decrease in the frequency of the Ca2+ oscillations [17, 53, 57, 75]. The mechanism slowing the Ca2+ oscillations appears to be mediated by a cAMP-dependent decrease in the sensitivity of the IP3R to IP3 [53]. In addition, the activity of PLCβ may also be simultaneously decreased to reduce the amount of IP3 available [73].

The mechanism of Ca2+ sensitivity also contributes to relaxation. In Ca2+-permeabilized lung slices, in the presence of sustained high Ca2+ and contractile agonist, β2-adrenergic agonists induced airway relaxation without altering the [Ca2+]i. This response implies a reduction in Ca2+ sensitivity. The importance of this mechanism in β2-adrenergic agonist mediated relaxation is emphasized by the action of formoterol. At very low concentrations, formoterol has little effect on the frequency of MCh-induced Ca2+ oscillations, yet, it relaxes the airway approximately 50% of the induced contraction [57]. This implies that formoterol initially acts by decreasing Ca2+ sensitivity. Airways, in lung slices, are also relaxed by nitric oxide [77]. Similarly, the frequency of the Ca2+ oscillations of the SMCs is slowed by a cGMP-mediated decrease in sensitivity of the IP3R to IP3. However, in contrast, to cAMP-induced relaxation, cGMP-induced relaxation does not appear to significantly alter Ca2+ sensitivity [77].

Although β2-adrenergic agonists are the mainstay of bronchodilators, there are a number of intriguing compounds that elicit airway relaxation. Stimulants of taste receptors appear to have a paradoxical action of increasing [Ca2+]i while inducing SMC relaxation [78]. An explanation of this response might be decreased Ca2+ sensitivity [79]. However, because the SMC Ca2+ signaling was measured in isolated cultured cells and SMC force was measured separately in muscle strips, this paradox requires confirmation by the simultaneous examination of each response in SMCs in lung slices. Other food compounds including ginger [80] and peony root extract [81] reduce airway contraction in a more conventional way, by decreasing SMC Ca2+ levels in lung slices; a response that is consistent with their use as herbal remedies. A reduction in sustained airway contraction and the frequency of ACh-induced Ca2+ oscillations has also been observed in response to an inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ in mouse lung slices [55]. The authors speculate that agonist activation of PI3Kγ, via Gβγ subunits may be required for Ca2+ oscillations.

e) Lung slices from transgenic animals

The development of lung slice technology using mice [10, 11, 82] provides the opportunity to use the specificity of the phenotypes of transgenic animals.

Airway hyperresponsiveness

In an earlier study with mice strains [83], it was determined that C3H/HeJ mice showed greater airway contractility and contraction velocity to ACh as compared to A/J mice and BALB/C mice. However, there were no apparent differences in the frequency of the Ca2+ oscillations induced by ACh in each mouse strain. The implication of this data is that the Ca2+ sensitivity differs between strains. This idea was not tested at the time as the methods for Ca2+ sensitivity studies in lung slices were not developed. However, this result that C3H/HeJ mice were more responsive than A/J mice contrasted to in vivo studies [82, 84, 85] where airway hyperresponsiveness was ordered as A/J > BALB/C > C3H/HeJ. One possible explanation for this difference is the in vivo use of an inhaled anesthetic, halothane [84], that greatly diminishes ACh-induced airway contraction and Ca2+ oscillations [11, 83]. An alternative explanation may arise from slice thickness; with ~75 μm thick lung slices, C3H/HeJ mice were the most reactive whereas with 0.5 mm lung slices, A/J mice were the most reactive. This is perhaps an example of where variations in lung slice thickness may have a significant effect. Subsequent studies from our laboratory have used thicker slices (~130 – 150 um [23]).

Our understanding of a disease process is accelerated by the availability of an appropriate animal model; for asthma these often consist of animals, particularly mice, sensitized to an allergen (e.g. ovalbumin). These animal models require considerable effort to produce but have limited use. Consequently, a transgenic animal representing the disease is desirable. For asthma, the T-bet knock out mouse has been proposed [86]. Consequently, the examination of airway responses of T-bet KO mice has been attempted to gain insights into airway-hyper-responsiveness [54, 87]. T-bet KO mice appear to have increased basal airway tone which correlated with increased spontaneous increases in [Ca2+]i of SMCs. The cause of this spontaneous activity was not ascertained but this type of Ca2+ signaling is not commonly observed in control BALB/C mice [16, 56, 60]. As might be predicted, T-bet KO mouse airways were hyper-responsive and this correlated with Ca2+ transients of increased magnitude combined with an increased numbers of SMCs showing Ca2+ oscillations as compared to control mice. Interestingly, similar behaviors of increased tone and/or contractility were induced in control lung slices exposed to IL-13 [54, 88].

Although the frequencies of the Ca2+ oscillations induced by ACh were similar for T-bet KO and control mice, these rates were substantially less than those found in other similar studies with BALB/C mice [16]. The emptying of internal Ca2+ stores resulted in higher transients than control mice implying that an overloaded Ca2+ may be the cause of the elevated Ca2+ signaling [54]. However, in another study, the opposite idea of under-filled Ca2+ stores is implied as a result of a deficient SERCA pump in asthmatic SMCs cells [89]. However, both conditions may result in increased basal tone and increased contraction; excessive Ca2+ within the store leading to elevated [Ca2+]i [89] by spontaneous Ca2+ release, most likely through ryanodine receptors [60], whereas weak SERCA activity would be inadequate to reduce [Ca2+]i to low levels and would prolonged any agonist-induced increases in [Ca2+]i.

Muscarinic receptors

The availability of transgenic mice lacking M1, M2, M3 or both M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors has provided a direct method for evaluating the specific contribution of each receptor sub-type to airway contraction [90]. In summary, the activation of both M2 and M3 receptors contributes to airway contraction, while the activation of the M1 receptor counteracts airway contraction. As with many studies with lung slices, the effects of these experimental manipulations have only been examined at the macroscopic level of airway contraction. An investigation of how each receptor contributes to Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+ sensitivity would be of value. The same mice were also useful in addressing the idea that 5HT might induce airway contraction via the release of ACh from the airway epithelium. However, 5HT was found to induce airway contraction (equivalent to that of wild type mice) in mice deficient for the M2 and M3 receptors [91]. These results are consistent with the failure of atropine to abolish airway contraction induced by 5HT [16, 91].

f) Allergenic Responses

Allergen-stimulated airway contraction is a common feature of asthma. Consequently, lung slices have been used to examine allergen-based responses. However, it is not always necessary to prepare lung slices from sensitized animals because lung slices can be passively sensitized with atopic serum [20]. The overnight exposure of rat lung slices to serum from rats sensitized to ovalbumin resulted in the substantial contraction of the airways upon exposure to ovalbumin. The mechanism mediating this response appeared to be the release of 5HT, presumably from mast cells, because ovalbumin-induced airway contraction was prevented only in the presence of the 5HT receptor antagonist, ketanserin [20]. Very similar results with human [15] and guinea pig [12] lung slices were obtained in response to ovalbumin or grass pollen. In addition, airway contraction could be induced by exposure to anti-IgE antibodies [15, 88], a result implying the allergen responses were occurring by the cross-linking of IgE-bound receptors. However, these latter responses were not mediated by 5HT, because ketanserin was without effect. In fact, human airways do not even respond to 5HT [12, 17], but contraction was largely prevented by a cocktail of antagonists targeted against thromboxane and leukotriene receptors [15]. Histamine receptors antagonists had effects in guinea pigs [12].

These results imply that the lung slices contain mast cells that can be primed to degranulate and that degranulation results in substantial contractile agonist release. However, it is surprising that slices from non-sensitized animals contain adequate numbers of mast cells to mediate these effects. The chambers used for these studies may help in the detection of this response as the released compounds are not washed away by continual perfusion and therefore may accumulate to an effective concentration. On the other hand, the high sensitivity of airways to leukotrienes is compatible with the expected low concentrations of contractile agonist released from the mast cells. However, the sensitivity of airways to 5HT is much less and this suggests that substantial amounts of 5HT must be released. Alternatively, mast cells may be well placed to exploit local signaling domains to generate local high concentrations. A second alternative to enhance contraction is that airway SMCs themselves may respond directly to allergen via their own IgE receptors [92].

In view of the use of sensitized animal models for investigating the basis of airway hyper-responsiveness in asthma, it is somewhat surprising that this approach has not met with much success with lung slices. In our laboratory, we have extensively attempted to detect changes in airway reactivity in ovalbumin sensitized mice (unpublished data). Similar results have been reported by Chew et al., [93] who confirmed that their acute and chronic sensitization procedures induced airway hyperresponsiveness in vivo and histological alterations of the airway. Our attempts to mimic the results of Dandurand et al., [94] which demonstrated hyper-responsive reactions with rat slices were also unsuccessful. Lung slices from mice sensitized with chemical allergen also failed to respond immediately to the allergens although airway responsiveness could be invoked with prolonged incubation [95].

g) Smoking toxicology

First and second-hand cigarette smoke is well recognized as a risk factor for lung disease. Consequently, exposure of lung slices to cigarette smoke extracts can provide a bioassay to evaluate these hazards. Interestingly, smoke-extract induced airway relaxation and reversed hyperreactivity in lung slices from T-bet KO mice. These responses appeared to be mediated by nicotine [96]. Rat lung slices treated with smoke particulate matter showed increases in kinin receptors and inflammation [97]. Alternatively, live animals can be exposed to smoke and the physiology of the lung slices subsequently examined. With this approach, mice airways displayed increased airway responsiveness after chronic exposure to smoke for 8 weeks. These responses correlated with IL-13 expression which itself, had an affect on mouse lung slices [54, 98]. Similarly, the responses of endothelial cells of intra-acinar pulmonary arteries were observed in guinea pig lung slices [99] and found to be dysfunction to ACh after exposure to smoke. More toxicological studies of this kind are reviewed in greater depth elsewhere [2].

5. Pathophysiology in lung slices

Although it has been long recognized that lungs are common sites for infection, the use of lung slices for the investigation of host-pathogen interactions is relatively sparse, but becoming more popular. The potential for this approach was confirmed with mouse lung slices infected with bacteria (Chlamydophila pneumoniae) and virus (respiratory syncytial virus) [100]. In a similar study, the pathogenicity of bovine parainfluenza virus 3 and bovine respiratory syncytial virus was examined in bovine lung slices [101] and compared to pathogenicity in a parallel assay system of differentiated cells, namely, air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures of airway epithelial cells [102]. While bovine parainfluenza virus 3 infected epithelial/ciliated cells of both lung slices and cultured cells, bovine respiratory syncytial virus did not infect epithelial cells in either cultured cells or lung slices. However, the bovine respiratory syncytial virus did infect other, although unidentified, cells deeper in the lung slice [101]. This raises the possibility that cells other than epithelial cells may be targets for viral infections of the lung and highlights the advantage of having all cell types present within the lung slice. A second advantage of the lung slice over the ALI system is time of preparation. ALI cultures take approximately 4 to 6 weeks to differentiate into epithelial-like cultures as compared to almost instant access to de novo differentiated airway wall. For human work, ALI cultures are an alternative if the tissue samples are limited, but human lung slices can be commonly obtained from surgical specimens and have been used to examine infection with adenovirus type 7 [103] or with anthrax spores [104]. Avian lung slices infected with infectious bronchitis virus for a week displayed an infection pattern based on strain and innoculum dose [105]. This distribution appeared to match the distribution or expression of the sialic-acid based receptor sites, detected with lectin, on the epithelial cells and used by the virus for infection.

In the studies above, cells infected with virus or bacteria were identified by immuno-fluorescence and confocal microscopy after freezing or chemically fixing the lung slices. Alternatively, green fluorescence protein, introduced as part of the viral genome, was expressed and detected in the lung slices after fixation. Because freezing often results in a loss of structural organization while chemical fixation commonly reduces antigenicity and/or fluorescence, the imaging of live infected lung slices would appear to be a better approach for the best resolution, especially with two-photon microscopy in which, due to auto-fluorescence, most cell types can be identified. In addition, a visualization of the infective process of cells may be possible in live lung slices.

Many different cells take part in host-pathogen interactions associated with the lung, including macrophages, dendritic cells and T-cells, and display interactions and migrations that are not well understood. However, the general approach of identifying these cells, either by green fluorescence protein expression or by labeling with tracker dyes, could be adapted to allow their movements to be followed in lung slices with time-lapse two-photon/confocal microscopy [106–108].

6. Some limitations of lung Slices

Although the lung slice is a versatile preparation and may have a role in many applications, it is important to point out that, like all other techniques, it is has limitations and that it is only one in a spectrum of techniques required to understand lung physiology. Many aspects of the lung slice that make it attractive for the study of multicellular activity preclude its use as an assay for biochemical, protein or gene analysis. However, techniques that can work with isolated single cells, such as laser capture micro-dissection, may overcome this limitation by extracting the cells of interest from the lung slice.

The anatomy of the lung slice may also be a disadvantage with respect to drug delivery or an infectious agent. The epithelial barrier is circumvented at the cut edge of the slice. Therefore, it is difficult to mimic deposition in the airway lumen that is a common therapeutic or invasive approach. One solution to this problem is the application of the agent in a living animal, followed by the preparation of lung slices at different times to evaluate the associated processes. Similarly, neural networks that run parallel to airways are unlikely to be intact in the lung slice. The presence of nerve endings also exemplifies the possibility of indirect actions of drugs though intermediate cell types. A common concern has been that stimulation of the nerves (e.g. depolarization with KCl) can mediate neurotransmitter release to induce a variety of responses including SMC contraction. However, in our early experiments, we determined such indirect effects were not a major problem; we found that KCl induced SMC contraction in the presence of MCh and 5HT receptor antagonists. However, the release of paracrine messengers from a variety of cell types, such as epithelial or mast cells must be constantly considered when interpreting the responses of lung slices to experimental stimulation.

Although not unique to the lung slice, many experimental studies are conducted with static tissues or cells. With respect to lungs this is especially important in view of the repetitive cycling of stretch and relaxation during breathing. In asthma, SMC stiffness is thought to be increased as result of a loss of response to this cyclic motion. Consequently, it is worth developing approaches to create a “breathing” lung slice. Clearly, ventilating air and/or circulating blood is not feasible but the repetitive stretching of the airway, via its parenchyma tethering, is possible by attaching the periphery of the lung slice to a flexible membrane.

7. Summary