Abstract

BACKGROUND

A large outbreak of diarrhea and the hemolytic–uremic syndrome caused by an unusual serotype of Shiga-toxin–producing Escherichia coli (O104:H4) began in Germany in May 2011. As of July 22, a large number of cases of diarrhea caused by Shiga-toxin–producing E. coli have been reported — 3167 without the hemolytic–uremic syndrome (16 deaths) and 908 with the hemolytic–uremic syndrome (34 deaths) — indicating that this strain is notably more virulent than most of the Shiga-toxin–producing E. coli strains. Preliminary genetic characterization of the outbreak strain suggested that, unlike most of these strains, it should be classified within the enteroaggregative pathotype of E. coli.

METHODS

We used third-generation, single-molecule, real-time DNA sequencing to determine the complete genome sequence of the German outbreak strain, as well as the genome sequences of seven diarrhea-associated enteroaggregative E. coli serotype O104:H4 strains from Africa and four enteroaggregative E. coli reference strains belonging to other serotypes. Genomewide comparisons were performed with the use of these enteroaggregative E. coli genomes, as well as those of 40 previously sequenced E. coli isolates.

RESULTS

The enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 strains are closely related and form a distinct clade among E. coli and enteroaggregative E. coli strains. However, the genome of the German outbreak strain can be distinguished from those of other O104:H4 strains because it contains a prophage encoding Shiga toxin 2 and a distinct set of additional virulence and antibiotic-resistance factors.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that horizontal genetic exchange allowed for the emergence of the highly virulent Shiga-toxin–producing enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 strain that caused the German outbreak. More broadly, these findings highlight the way in which the plasticity of bacterial genomes facilitates the emergence of new pathogens.

In early May 2011, an outbreak of diarrhea with associated hemolytic–uremic syndrome began in northern Germany; cases have subsequently been reported in 15 other countries. As of July 22, a total of 3167 cases of non–hemolytic–uremic syndrome Shiga-toxin–producing Escherichia coli (16 deaths) and 908 cases of hemolytic–uremic syndrome (34 deaths) have been reported, according to the German Protection against Infection Act. Several groups reported that the outbreak was caused by a Shiga-toxin–producing E. coli strain belonging to serotype O104:H4, with virulence features that are common to the enteroaggregative E. coli pathotype.1–3 This unusual E. coli serotype has previously been associated with sporadic cases of human disease4,5 but not with large-scale outbreaks.

E. coli are ordinarily commensal organisms, but six pathotypes of diarrheagenic E. coli are recognized, each with distinct phenotypic and genetic traits.6 Diarrhea associated with the hemolytic–uremic syndrome and neurologic complications is generally caused by E. coli that produce Shiga toxins.6 The majority of such strains, often referred to as enterohemorrhagic E. coli, contain the enterocyte effacement pathogenicity island, which facilitates colonization of the large intestine. Unexpectedly, polymerase-chain-reaction assays1–3 revealed that the German outbreak strain lacked this pathogenicity island, and the rapidly released results of genomic sequencing7 and cell adherence assays1 confirmed the initial observations that the German O104:H4 outbreak strain was an enteroaggregative E. coli strain rather than a typical enterohemorrhagic E. coli strain. The outbreak strain was similar to enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 strain 55989, isolated from a patient in the Central African Republic who had human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) with persistent diarrhea,8 which did not produce Shiga toxin.

The enteroaggregative E. coli pathotype has been implicated as an etiologic agent of diarrhea in travelers,9 children,10,11 and HIV-infected patients,12 as well as of several, probably foodborne outbreaks.13–16 Enteroaggregative E. coli are widespread among human populations, although the basis of the variation in the virulence of enteroaggregative E. coli is poorly understood.17 Enteroaggregative E. coli with proven pathogenicity typically contain a large set of virulence-associated genes regulated by the AggR transcription factor. These include plasmid genes encoding the aggregative adherence fimbriae (AAF),8,18–20 which anchor the bacterium to the intestinal mucosa and induce inflammation,21 as well as a protein-coat secretion system (Aat), its secreted dispersin protein,22 and a putative type VI secretion system termed Aai.23 Enteroaggregative E. coli strains often elaborate toxins and a variable number of serine protease autotransporters of Enterobacteriaceae (SPATEs) implicated in mucosal damage and colonization.24

Before the current outbreak of enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4, only three enteroaggregative E. coli genomes had been sequenced25–27; thus, genome-scale knowledge of the phylogeny of enteroaggregative E. coli was limited. We used third-generation DNA-sequencing technology to rapidly determine the genome sequences of the E. coli O104:H4 outbreak strain, seven other enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 strains, and four reference strains (Table 1).28–32

Table 1.

Isolates of Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli Sequenced or Analyzed in This Study.*

| Isolate† | Serotype | Location of Isolate | Source of Isolate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O42 | O44:H18 | Peru | Stool sample from child with diarrhea | Nataro et al.28 |

| 17-2 | O3:H2 | Chile | Stool sample from child with diarrhea | Vial et al.29 |

| JM221 | O92:H33 | Mexico | Stool sample from adult with diarrhea | Mathewson et al.30 |

| C1010-00 | Orough:H- | Denmark | Stool sample from child with diarrhea | Olesen et al.31 |

| 55989 | O104:H4 | Central African Republic | Stool sample from adult with diarrhea | Bernier et al.8 and Touchon et al.26 |

| C35-10‡ | O104:H4 | Africa | Stool sample from child with diarrhea | SSI collections |

| C682-09‡ | O104:H4 | Africa | Stool sample from child with diarrhea | SSI collections |

| C734-09‡ | O104:H4 | Africa | Stool sample from child without diarrhea | SSI collections |

| C754-09‡ | O104:H4 | Africa | Stool sample from child without diarrhea | SSI collections |

| C760-09‡ | O104:H4 | Africa | Stool sample from child without diarrhea | SSI collections |

| C777-09‡ | O104:H4 | Africa | Stool sample from child with diarrhea | SSI collections |

| TY2482 | O104:H4 | Germany | Stool sample from adult with diarrhea | Rohde et al.32 |

| LB226692 | O104:H4 | Germany | Diarrhea in adult | GenBank accession number, AFOB00000000 |

| H112180280 | O104:H4 | Germany | Diarrhea in adult | www.hpa-bioinformatics.org.uk/lgp/genomes |

| C227-11 | O104:H4 | Denmark | Diarrhea in adult | This study |

All the isolates listed were sequenced (55989 and O42 were resequenced, and the others were newly sequenced) in this study, with the exception of TY2482, LB226692, and H112180280. SSI denotes Statens Serum Institute.

Isolates shown in bold type are from the current outbreak (May 2011).

These isolates are not from a single clonal outbreak and thus represent population-based diversity in the O104:H4 group.

METHODS

ISOLATES

We isolated an enteroaggregative E. coli strain, C227-11, from a 64-year-old woman from Hamburg, Germany, who was hospitalized at Hvidovre University Hospital, Copenhagen. She presented with bloody diarrhea; the hemolytic–uremic syndrome did not develop. We selected five reference isolates (JM221, 17-2, 042, 55989, and C1010-00) to represent the best-studied enteroaggregative E. coli strains and to capture the geographic, serotype, and virulence-factor diversity of the enteroaggregative E. coli pathotype. We cultured six O104:H4 clinical isolates that we obtained from the Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen (C35-10, C682-09, C734-09, C754-09, C760-09, and C777-09), the five enteroaggregative E. coli reference isolates, and the C227-11 isolate. (Details regarding culture conditions are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.)

DNA PREPARATION, SEQUENCING, AND COMPARATIVE ANALYSES

We purified and sequenced the genomic DNA from C227-11, from six African enteroaggregative E. coli clinical isolates, and from five prototype enteroaggregative E. coli isolates with the use of PacBio RS DNA sequencers (Sequence Read Archive accession number, SRA038239; GenBank accession number, AFST00000000). We also carried out a comparative analysis with the sequence of another outbreak isolate, TY2482. (See the article by Rohde et al. elsewhere in this issue of the Journal for an analysis of sequence data obtained from TY2482.32) The Supplementary Appendix provides additional details regarding DNA sequencing,33,34 assembly, resequencing analysis, and detection of DNA structural variations, as well as the construction of phylogenetic trees and the characterization of lambdalike phage elements, virulence factors, plasmids, and regions unique to the outbreak strain.

RESULTS

GENOME SEQUENCING AND ASSEMBLY OF 13 E. COLI GENOMES

Using three sequencing instruments in parallel, we obtained coverage by a factor of approximately 75 for each of the isolates sequenced (mean read length, 2067 bases), in approximately 5 hours per isolate (Table 1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

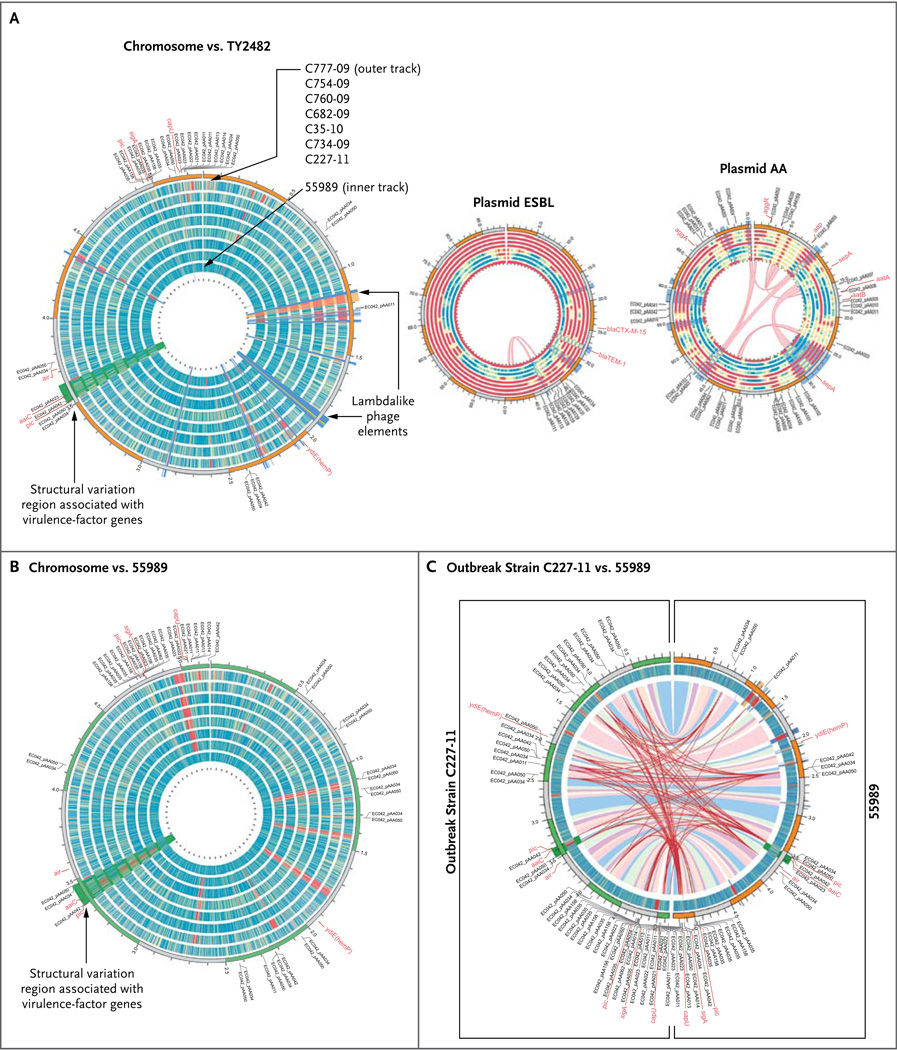

We used an integrative process (Fig. 1 in the Supplementary Appendix) to assemble the C227-11 genome and obtained 33 contigs (N50 of 402 kb and a maximum contig size of 622 kb), covering 99.7% of the bacterial chromosome at a level of accuracy of 99.97% (Table 3 in the Supplementary Appendix). (A contig is a contiguous sequence of DNA with no gaps; N50 is the contig length so that all contigs of that length or greater cover 50% of the bases in the genome.) Four additional contigs covered two large plasmids (approximately 88 kb and 75 kb) and a third 1.5-kb plasmid. The 1.5-kb plasmid could be fully resolved with two reads (Fig. 1 and Table 2 in the Supplementary Appendix). One of the plasmids is similar to the pAA plasmid found in typical enteroaggregative E. coli isolates.25 The pAA plasmid of C277-11 (referred to here as pAA C277-11) encodes aggregative adherence fimbriae (the AAF/I variant), the Aat complex, the dispersin protein, AggR, and other virulence factors characteristic of enteroaggregative E. coli (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of Genomes of Eight Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli O104:H4 Isolates.

In Panel A, the eight circular bands represent the tracks for the different enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) O104:H4 isolates sequenced in our study (from inner to outer tracks: 55989, C227-11, C734-09, C35-10, C682-09, C760-09, C754-09, and C777-09). These different bands represent coverage plots mapped against the reference genome TY2482, with blue or green indicating a high degree of coverage, yellow moderate coverage, and orange or red little or no coverage. The C227-11 coverage plot indicates near-complete sequence identity with the TY2482 genome. The annotations on the outside of the chromosome plot highlight positions of known virulence-factor genes and genes previously characterized on the AA plasmid in the E. coli O42 strain. The band ordering and color coding for the plasmids are the same as those described for the chromosome plot. The thin red lines in the pAA plot show internal repeats between 55989 and C227-11 that highlight shuffling of these elements around the plasmid sequence. In Panel B, the reference genome is 55989. Panel C shows a comparison between the genome of the outbreak strain C227-11 (left semicircle) and the 55989 genome (right semicircle), mapped against the 55989 genome and the genome of the outbreak strain TY2482, respectively. The colored ribbons inside the innermost track (blue, pink, and purple) represent homologous mappings between the two genomes, C227-11 and 55989, indicating a high degree of similarity between these genomes. The red lines show the chromosomal positioning of repeat elements, such as insertion sequences and other mobile elements, which reveal more heterogeneity between the genomes than is evident from mapping regions of homology.

We compared the sequence of C227-11 with the six O104:H4 strains from Africa, the previously released sequence data from outbreak-linked isolates, the available reference-genome sequences for the outbreak isolate TY2482, and the African enteroaggregative E. coli 55989 strain,8,26 in order to identify copy-number variations and small nucleotide variations among all the isolates (Fig. 1, and Table 3 and Fig. 3 in the Supplementary Appendix). (See animation at NEJM.org.) The genomes of the isolates from the current outbreak (C227-11, TY2482, LB226692, and H112180280) were very similar, with only 236 differences in single-nucleotide variants detected between TY2482 and C227-11 (Table 3 and Fig. 3 in the Supplementary Appendix), suggesting that the outbreak is clonal. We observed structural variations between the C227-11 genome and the complete genome sequence of TY2482, based in part on the recently described draft assembly,32 that seem unlikely to be the result of misassemblies in the C227-11 genome, because these regions are identical in the C227-11 and H112180280 genomes (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 in the Supplementary Appendix). However, we observed larger-scale deletions, insertions, inversions, and other structural variations between the O104:H4 outbreak isolates and the seven other enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 isolates we sequenced (Fig. 1).

Several of the structurally divergent regions house genes that encode virulence factors. For example, C227-11 contains two lambdalike prophage elements, one of which contains the genes for Shiga toxin. The toxin-encoding phage is observed only in the outbreak isolate (Fig. 1, orange highlight), whereas the other prophage element (Fig. 1, blue highlight) is present in several additional O104:H4 isolates. Figure 1 also reveals regions unique to the outbreak-strain chromosome, including structural variation in regions that include virulence-factor genes such as pic and the aai pathogenicity island (Fig. 1, green highlight). This particular region includes differences between the outbreak isolates and 55989 (Fig. 6 in the Supplementary Appendix).

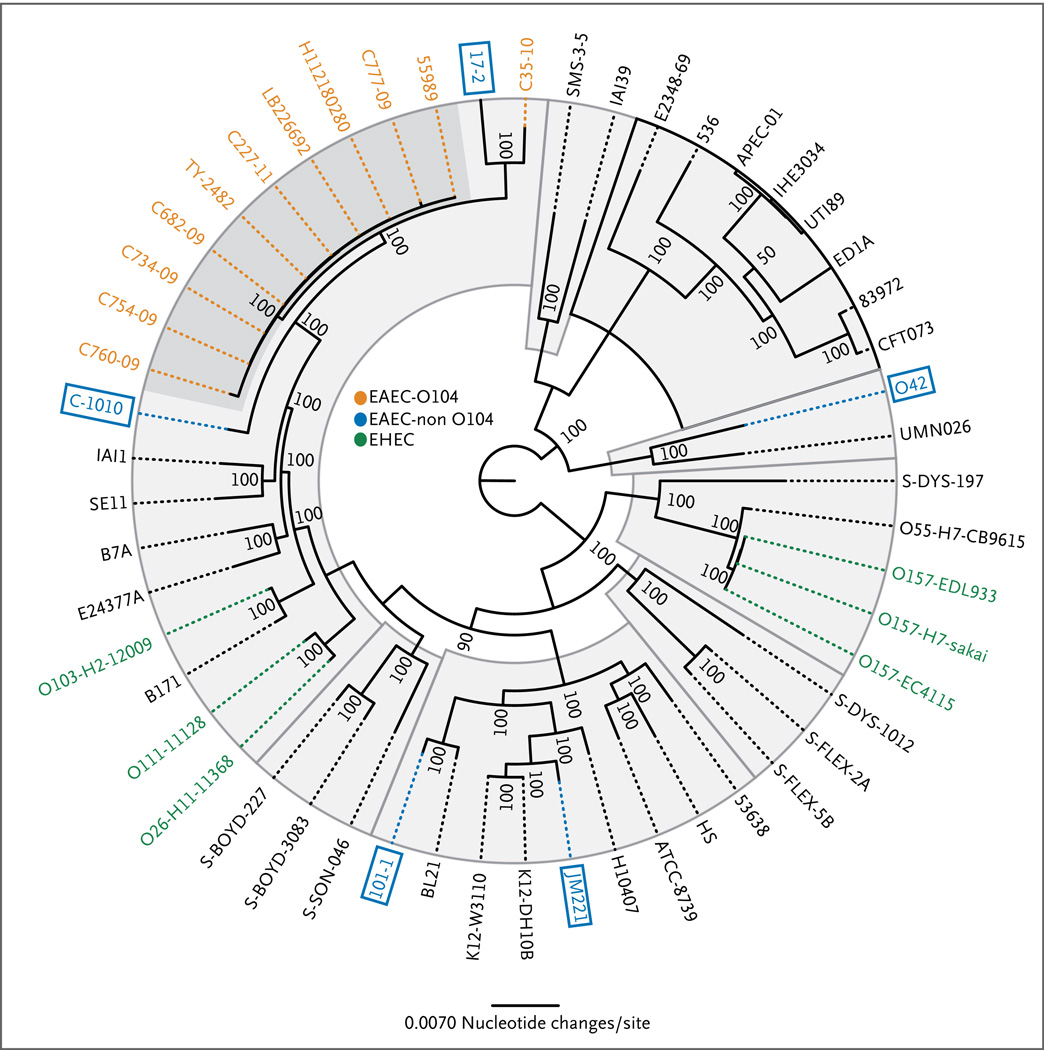

WHOLE-GENOME PHYLOGENY

We used approximately 2.56 Mb of DNA, representing the conserved core genome found in 53 E. coli and shigella genomes, including C277-11, other German outbreak strains, and the African O104:H4 strains, to generate a phylogenic tree depicting the evolution of E. coli (Fig. 2, and Fig. 4 and Table 4 in the Supplementary Appendix). We observed enteroaggregative E. coli isolates spread through the entire phylogenetic tree (blue boxes), suggesting that, with respect to genome composition, they are the most diverse of the pathotypes. However, the enteroaggregative E. coli strains of O104:H4 serotype (orange) form a distinct clade, with highly conserved core genomes (with one O104:H4 isolate, C35-10, being an outlier). The genetic similarity between the Shiga-toxin–encoding strains isolated in the German outbreak and numerous enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 strains lacking the Shiga-toxin–encoding phage suggests that acquisition of the phage was a relatively recent event (Fig. 4 in the Supplementary Appendix). The presence of the O104:H4 outbreak strain within the enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 clade confirms that the outbreak strain is not a prototypical enterohemorrhagic E. coli strain that has acquired the virulence features of enteroaggregative E. coli.

We analyzed the phylogeny of only the enteroaggregative E. coli isolates, on the basis of 3.48 Mb of shared genome sequences (Fig. 7 in the Supplementary Appendix). The O104:H4 isolates, including the outbreak isolates, clustered into a single, closely related clade — again, with the exception of the C35-10 isolate. The four isolates from the German outbreak (TY2482, C227-11, LB226692, and H112180280), three of which were sequenced by other groups, are particularly closely related.

THE LAMBDALIKE PHAGE CONTAINING THE STX2 GENES

A polymerase-chain-reaction assay revealed that the outbreak isolates contained genes encoding Shiga toxin 2,3 a toxin that inhibits protein synthesis and causes the hemolytic–uremic syndrome.6 The insertion site of the Shiga-toxin–encoding lambdalike prophage in the outbreak strain is similar to that of the Shiga-toxin–encoding lambdalike prophage in E. coli strain EDL933. Moreover, the similarity between 933W (the Shiga-toxin–producing phage carried by EDL933) and the prophage of the outbreak strain — particularly in the regions that flank the Shiga toxin genes, which control Shiga toxin production and toxin release (Fig. 8 and 9 in the Supplementary Appendix) — suggests that production of Shiga toxin 2 by the outbreak strain may be increased by certain antibiotics.36 Consistent with this possibility is our finding that growth of C227-11 in medium containing ciprofloxacin (25 ng per milliliter) increased expression of the stxAB2 genes by a factor of about 80 (Fig. 10 in the Supplementary Appendix), which is similar to the elevation of Shiga toxin 2 expression reported for the enterohemorrhagic E. coli strain EDL933 after exposure to ciprofloxacin.36

OTHER VIRULENCE FACTORS IN THE OUTBREAK-STRAIN GENOME

The high prevalence of the hemolytic–uremic syndrome among persons affected in the German outbreak suggests that the enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 strain that caused the outbreak has additional virulence factors or a particular combination of virulence factors that make it extremely pathogenic (Table 5 in the Supplementary Appendix). The genome of the outbreak strain has many virulence-factor genes commonly found in enteroaggregative E. coli, including several for which production is coordinately regulated by the AggR transcription activator (Fig. 11 in the Supplementary Appendix); these include the genes encoding AAF/I (aggA-D), dispersin (aap), and the dispersin translocator (aatPABCD). With the exception of stxAB2, genes characteristic of enterohemorrhagic E. coli are not present in the C227-11 genome. Together, these observations provide support for classifying the outbreak strain as an enteroaggregative E. coli strain.

Among the virulence factors of the German outbreak strain that are common in enteroaggregative E. coli and other diarrheagenic E. coli strains (and shigella species) are the SPATEs.37 However, the C227-11 genome encodes a combination of SPATEs (SepA, SigA, and Pic) rarely reported in enteroaggregative E. coli strains.37 This combination was also present in three of the African strains we studied, as well as in 55989. It is also unusual for an enteroaggregative E. coli strain to encode more than two SPATEs.37 Thus, the number and combination of SPATEs in the outbreak strain may contribute to its heightened virulence. Other potential virulence factors identified in the German outbreak strain include long polar fimbriae (lpf) and IrgA homologue adhesion (iha),1 which have previously been identified both in enterohemorrhagic E. coli and in other E. coli pathotypes.38,39

UNIQUE REGIONS IN THE C227-11 GENOME

The C227-11 genome contains 58 regions longer than 100 bp that are missing in at least 1 of the other 11 prototype enteroaggregative E. coli genomes (Table 6 in the Supplementary Appendix). These 58 regions contain 180,088 bp (about 3.4% of the genome), but more than 120,000 bp of this unique DNA comprise the two lambdalike phages mentioned above (61,022 and 59,914 bp, respectively). Most of the remaining sequence (about 60,000 bp) is made up of genes of unknown function that are also found in commensal E. coli and thus probably do not contribute to virulence. This paucity of novel DNA further supports the recent emergence of the O104:H4 lineage. As depicted in Figure 1, sequences absent from C227-11 relative to the reference strain 44898 are also absent from other O104:H4 isolates. Thus, our sequence analyses suggest that acquisition of stx2, perhaps enhanced by an unusual complement of SPATEs, could account for the elevated virulence of C227-11.

PLASMID SEQUENCES AND OTHER MARKERS OF CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

We mapped raw sequences from the 12 isolates to the three plasmid sequences assembled as part of the TY2482 outbreak genome (Fig. 1) (GenBank accession number, AFOG01000000). The largest and smallest plasmids did not contain genes encoding any known virulence factors. However, the largest plasmid, pESBL C227-11, which encodes the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15, is very similar to the pEC_Bactec plasmid found in several clinical E. coli isolates.40 The pESBL C227-11 plasmid was not identified in most of the O104:H4 genomes sequenced, suggesting that this plasmid might be a recent acquisition by some strains or, alternatively, might be relatively unstable and consequently lost by numerous strains.

The intermediate-size plasmid pAA C227-11 (Fig. 1) is approximately 75,000 bp and resembles the pAA plasmid identified in enteroaggregative E. coli isolates,25,26 although marked diversity is also evident within this family of plasmids. Comparison of the pAA C227-11 plasmid with the prototype pAA plasmid from enteroaggregative E. coli 042 identified only about 34,000 bp of shared sequence, and pAA C227-11 shares only 28,000 bp of the sequence with the 55989 virulence plasmid. The sequence heterogeneity among pAA plasmids in enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 is much greater than that between chromosome sequences, with conservation found in core virulence features. The pAA C227-11 plasmid encodes a number of enteroaggregative E. coli–specific virulence factors (Fig. 1, and Tables 8 and 9 in the Supplementary Appendix), such as aggR and genes that it regulates, including AggR, AatPA–D, Aap, AggA–D, and SepA, and thus presumably is critical for C227-11 pathogenicity.

DISCUSSION

The outbreak clone is a dramatic example of gene acquisition by means of lateral transfer that resulted in an accretion of synergistic virulence factors. By all molecular definitions, it is an enteroaggregative E. coli strain but one that has acquired a Shiga-toxin–encoding phage — a hallmark of Shiga-toxin–producing E. coli. Our findings suggest that critical events in the evolution of the German enteroaggregative E. coli outbreak strain included the acquisition of a Stx-encoding prophage and a plasmid bearing an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase gene by an ancestral precursor of this strain (Fig. 11 in the Supplementary Appendix). However, analyses of the genomes of contemporary isolates cannot reveal the true complexity of the evolutionary pathway that yielded the Shigatoxin–producing enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4 outbreak strain. The outbreak is not the first clinically linked instance of an enteroaggregative E. coli acquiring a Shiga-toxin–encoding phage,41,42 but it is a clear case of such a strain causing a major outbreak of disease. Whether the current outbreak is due to a particularly virulent Shiga-toxin–positive enteroaggregative E. coli, a rare epidemiologic opportunity, or both remains unclear.

The similarity between the Shiga-toxin–encoding prophage in the outbreak isolate and such prophages in enterohemorrhagic E. coli, particularly in the toxin promoter region, suggests that toxin-inducing conditions might be similar for these pathogens. Our observation that toxin production by the O104:H4 outbreak strain is induced by a quinolone antibiotic, as previously seen with enterohemorrhagic E. coli strains,36 suggests that caution is warranted in the use of certain classes of antibiotics to counteract this newly emerged pathogen.

The current isolate diverges from common enteroaggregative E. coli isolates in the number and nature of its SPATE proteases. Most diarrheagenic E. coli strains encode a single SPATE, and enteroaggregative E. coli strains ordinarily encode two SPATEs37; the presence of three SPATE-encoding genes in the outbreak strain is unusual. One of these SPATEs, Pic, is common among enteroaggregative E. coli strains and cleaves host intestinal epithelial-cell mucins, thereby promoting intestinal colonization,43 and mucin-related glycoproteins associated with leukocyte immune functions.44 The outbreak strain also encodes SigA, a SPATE that cleaves the cytoskeletal protein spectrin, inducing rounding and exfoliation of enterocytes.45 The third SPATE, SepA, is associated with increased enteroaggregative E. coli virulence, but its function is unknown (unpublished observations). We speculate that the combined activity of these SPATEs, together with other enteroaggregative E. coli virulence factors, accounts for the increased uptake of Shiga toxin into the circulation, resulting in the high rates of the hemolytic–uremic syndrome.

Finally, the worldwide efforts to sequence and analyze the genome of the German enteroaggregative E. coli outbreak strain illustrate the power of emerging high-throughput DNA-sequencing technologies. The ability to sequence genomes within hours (rather than days to weeks) with unprecedented read lengths is the emerging hallmark of third-generation DNA sequencing; such long reads facilitate new genome-assembly efforts and deeper insights into structural variations. The rapid sequencing of isolates from this outbreak (and from related strains) has yielded critical insight into its causative agent. In addition, the rapid release of DNA sequence data by the Beijing Genomics Institute (an analysis of which is described by Rohde and colleagues32) allowed analyses of a bacterial outbreak by communities of researchers to proceed with extraordinary speed, providing a glimpse into a new era in which communities of researchers rapidly share large-scale data sets and analyses that are vital for public health.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2. Phylogenetic Comparisons of 53 Escherichia coli and Shigella Isolates.

Genomic sequences were compared with the use of 100 bootstrap calculations, as described by Sahl et al.35 The species-based phylogeny was inferred with the use of 2.56 Mbp of the conserved core genome. The O104:H4 isolates are shown in orange, the reference enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) isolates in blue, and the enterohemorrhagic E. coli isolates in green. (The classification of the other strains is shown in Fig. 4 and Table 4 in the Supplementary Appendix.) The O104:H4 isolates cluster into a single clade (dark gray); in contrast, the reference EAEC isolates are extremely divergent and are represented throughout the phylogeny.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the University of Maryland Internal Funds and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (AI090873, to the University of Maryland School of Medicine), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the NIH (R37-AI-42347, to Dr. Waldor), the NIH (AI-033096, to Drs. Nataro and Boisen), and the Danish Council for Strategic Research (09-063070, to Dr. Krogfelt).

We thank the organizations and individuals who continue to provide outstanding patient care during this outbreak; Steve Turner, Hugh Martin, and Michael Phillips (Pacific Biosciences) for their thoughtful discussions, advice, and support; Brigid Davis (Harvard Medical School) for helpful comments on the manuscript; Susanne Jespersen and Pia Møller Hansen at the World Health Organization Reference Laboratory at Statens Serum Institute for technical assistance; and Edwin Hauw for assistance in uploading sequencing data to the National Center for Biotechnology Information databases.

Footnotes

An animation comparing the outbreak strain genome with genomes of other strains is available at NEJM.org

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bielaszewska M, Mellmann A, Zhang W, et al. Characterisation of the Escherichia coli strain associated with an outbreak of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Germany, 2011: a microbiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 June 22; doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70165-7. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank C, Werber D, Cramer JP, et al. Epidemic profile of Shiga-toxin–producing Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak in Germany — preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2011 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheutz F, Nielsen EM, Frimodt-Moller J, et al. Characteristics of the enteroaggregative Shiga toxin/verotoxinproducing Escherichia coli O104:H4 strain causing the outbreak of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Germany, May to June 2011. Euro Surveill. 2011;16:pii:19869. doi: 10.2807/ese.16.24.19889-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellmann A, Bielaszewska M, Kock R, et al. Analysis of collection of hemolytic uremic syndrome-associated enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1287–1290. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae WK, Lee YK, Cho MS, et al. A case of hemolytic uremic syndrome caused by Escherichia coli O104:H4. Yonsei Med J. 2006;47:437–439. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2006.47.3.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupferschmidt K. Germany. Scientists rush to study genome of lethal E. coli. Science. 2011;332:1249–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.332.6035.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernier C, Gounon P, Le Bouguenec C. Identification of an aggregative adhesion fimbria (AAF) type III-encoding operon in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli as a sensitive probe for detecting the AAFencoding operon family. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4302–4311. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4302-4311.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adachi JA, Jiang ZD, Mathewson JJ, et al. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli as a major etiologic agent in traveler’s diarrhea in 3 regions of the world. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1706–1709. doi: 10.1086/320756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tompkins DS, Hudson MJ, Smith HR, et al. A study of infectious intestinal disease in England: microbiological findings in cases and controls. Commun Dis Public Health. 1999;2:108–113. [Erratum, Commun Dis Public Health 1999; 2: 222.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okeke IN, Lamikanra A, Czeczulin J, Dubovsky F, Kaper JB, Nataro JP. Heterogeneous virulence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains isolated from children in Southwest Nigeria. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:252–260. doi: 10.1086/315204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wanke CA, Mayer H, Weber R, Zbinden R, Watson DA, Acheson D. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli as a potential cause of diarrheal disease in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:185–190. doi: 10.1086/515595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobeljić M, Miljković-Selimović B, Paunović-Todosijević D, et al. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli associated with an outbreak of diarrhoea in a neonatal nursery ward. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:11–16. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800001072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eslava CVJ, Morales R, Navarro A, Cravioto A. Identification of a protein with toxigenic activity produced by enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Program and Abstracts of the 93rd General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology; May 16–20, 1993; Atlanta. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Nelson WE. Nelson essentials of pediatrics. 4th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Itoh Y, Nagano I, Kunishima M, Ezaki T. Laboratory investigation of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli O untypeable:H10 associated with a massive outbreak of gastrointestinal illness. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2546–2550. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2546-2550.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang DB, Okhuysen PC, Jiang ZD, DuPont HL. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli: an emerging enteric pathogen. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:383–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nataro JP, Deng Y, Maneval DR, German AL, Martin WC, Levine MM. Aggregative adherence fimbriae I of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli mediate adherence to HEp-2 cells and hemagglutination of human erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2297–2304. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2297-2304.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czeczulin JR, Balepur S, Hicks S, et al. Aggregative adherence fimbria II, a second fimbrial antigen mediating aggregative adherence in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4135–4145. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4135-4145.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boisen N, Struve C, Scheutz F, Krogfelt KA, Nataro JP. New adhesin of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli related to the Afa/Dr/AAF family. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3281–3292. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01646-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrington SM, Strauman MC, Abe CM, Nataro JP. Aggregative adherence fimbriae contribute to the inflammatory response of epithelial cells infected with enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1565–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheikh J, Czeczulin JR, Harrington S, et al. A novel dispersin protein in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1329–1337. doi: 10.1172/JCI16172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dudley EG, Thomson NR, Parkhill J, Morin NP, Nataro JP. Proteomic and microarray characterization of the AggR regulon identifies a pheU pathogenicity island in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1267–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dutta PR, Cappello R, Navarro-Garcia F, Nataro JP. Functional comparison of serine protease autotransporters of enterobacteriaceae. Infect Immun. 2002;70:7105–7113. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.7105-7113.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaudhuri RR, Sebaihia M, Hobman JL, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative metabolic profiling of the prototypical enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strain 042. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1):e8801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Touchon M, Hoede C, Tenaillon O, et al. Organised genome dynamics in the Escherichia coli species results in highly diverse adaptive paths. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(1):e1000344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasko DA, Rosovitz MJ, Myers GS, et al. The pangenome structure of Escherichia coli: comparative genomic analysis of E. coli commensal and pathogenic isolates. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6881–6893. doi: 10.1128/JB.00619-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nataro JP, Baldini MM, Kaper JB, Black RE, Bravo N, Levine MM. Detection of an adherence factor of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli with a DNA probe. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:560–565. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vial PA, Robins-Browne R, Lior H, et al. Characterization of enteroadherent-aggregative Escherichia coli, a putative agent of diarrheal disease. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:70–79. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathewson JJ, Oberhelman RA, Dupont HL, Javier de la Cabada F, Garibay EV. Enteroadherent Escherichia coli as a cause of diarrhea among children in Mexico. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1917–1919. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.10.1917-1919.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olesen B, Neimann J, Böttiger B, et al. Etiology of diarrhea in young children in Denmark: a case-control study. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3636–3641. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3636-3641.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohde H, Qin J, Cui Y, et al. Open-source genomic analysis of Shiga-toxin–producing E. coli O104:H4. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:718–724. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chin CS, Sorenson J, Harris JB, et al. The origin of the Haitian cholera outbreak strain. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:33–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Travers KJ, Chin CS, Rank DR, Eid JS, Turner SW. A flexible and efficient template format for circular consensus sequencing and SNP detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(15):e159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahl JW, Steinsland H, Redman JC, et al. A comparative genomic analysis of diverse clonal types of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli reveals pathovar-specific conservation. Infect Immun. 2011;79:950–960. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00932-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, McDaniel AD, Wolf LE, Keusch GT, Waldor MK, Acheson DW. Quinolone antibiotics induce Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages, toxin production, and death in mice. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:664–670. doi: 10.1086/315239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boisen N, Ruiz-Perez F, Scheutz F, Krogfelt KA, Nataro JP. Short report: high prevalence of serine protease autotransporter cytotoxins among strains of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:294–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres AG, Blanco M, Valenzuela P, et al. Genes related to long polar fimbriae of pathogenic Escherichia coli strains as reliable markers to identify virulent isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2442–2451. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00566-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wieser A, Romann E, Magistro G, et al. A multiepitope subunit vaccine conveys protection against extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in mice. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3432–3442. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00174-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smet A, Van Nieuwerburgh F, Vandekerckhove TT, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of CTX-M-15-plasmids from clinical Escherichia coli isolates: insertional events of transposons and insertion sequences. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morabito S, Karch H, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, et al. Enteroaggregative, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O111:H2 associated with an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:840–842. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.840-842.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iyoda S, Tamura K, Itoh K, et al. Inducible stx2 phages are lysogenized in the enteroaggregative and other phenotypic Escherichia coli O86:HNM isolated from patients. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;191:7–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harrington SM, Sheikh J, Henderson IR, Ruiz-Perez F, Cohen PS, Nataro JP. The Pic protease of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli promotes intestinal colonization and growth in the presence of mucin. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2465–2473. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01494-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruiz-Perez F, Wahid R, Faherty CS, et al. Serine protease autotransporters from Shigella flexneri and pathogenic Escherichia coli target a broad range of leukocyte glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101006108. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Hasani K, Navarro-Garcia F, Huerta J, Sakellaris H, Adler B. The immunogenic SigA enterotoxin of Shigella flexneri 2a binds to HEp-2 cells and induces fodrin redistribution in intoxicated epithelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(12):e8223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.