Abstract

Microglia, the resident microphages of the CNS, are rapidly activated after ischemic stroke. Inhibition of microglial activation may protect the brain by attenuating blood-brain barrier damage and neuronal apoptosis after ischemic stroke. However, the mechanisms by which microglia is activated following cerebral ischemia is not well defined. In present study we investigated the expression of PI3Kgamma in normal and ischemic brains and found that PI3Kgamma mRNA and protein are constitutively expressed in normal brain microvessels, but significantly upregulated in postischemic brain primarily in activated microglia following cerebral ischemia. In vitro, the expression of PI3Kgamma mRNA and protein was verified in mouse brain endothelial and microglial cell lines. Importantly, absence of PI3Kgamma blocked the early microglia activation (at 4h) and subsequent expansion (at 24-72 h) in PI3Kγ knockout mice. The results suggest that PI3Kγ is an ischemia-responsive gene in brain microglia and contributes to ischemia-induced microglial activation and expansion.

Keywords: phosphoinositide 3-kinase-gamma, ischemia, microglia, endothelial cells, stroke

Introduction

Cerebral ischemia initiates a cascade of cellular and molecular events that lead to brain inflammation and tissue damage, which are characterized by a rapid activation of resident cells (microglia, astrocytes and neurons), followed by the infiltration of circulating leukocytes (neutrophils, macrophages and T-cells), as well as release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and proinflammatory mediators (cytokines and chemokines) [1]. Microglia, the resident macrophages of the brain, are among the first cells respond to brain injury [2], When activated, microglia undergo proliferation, chemotaxis, and morphological changes. Several studies have suggested that ischemia-activated microglia play an adverse role in the pathogenesis of stroke. Microglia may potentiate damage to blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity and endanger neuronal survival through the release of ROS or proinflammatory cytokines and other neurotoxins [2,3]. Inhibition of microglial activation may protect the brain after ischemic stroke by limiting BBB disruption and reducing edema and hemorrhagic transformation [4]. Thus, modulation of microglial activation might be a potential therapeutic approach for stroke and other neurovascular disorders [4]. Nevertheless, most of the detailed mechanisms by which microglia is activated following cerebral ischemia are not elucidated.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma (PI3Kγ), the class Ib PI3K, is expressed highly in leukocytes and also in endothelial cells and regulates different cellular functions relevant to inflammation and tissue damage [5-7]. PI3Kγ can be activated by G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) [5] and also by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα [8]. Experimental and clinical data indicate that many GPCR ligands, such as chemokines (e.g. MCP-1, IL-8) [9, 10], oxidized LDL [11], thrombin [12], angiotensin II [13,14], as well as cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β) [9,10] are elevated in ischemic brain tissue and/or in plasma before stroke onset or within early hours after stroke, as demonstrated in animal models and in stroke patients. Thus, activation of PI3Kγ could represent a common downstream signaling pathway, on which the effects of multiple proinflammatory mediators converge in ischemic stroke. However, little is known about the role of PI3Kγ in stroke and other neurovascular disorders. In this study, we examined the expression of PI3Kγ in the normal and ischemic brain and its involvement in the activation of microglia in acute experimental stroke in mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6J mice (wild type [WT]) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). PI3K-p110γ knockout (PI3Kγ–/–) mice on the C57BL/6J background were made by J.M.P. [15], transferred to the LSU Health Sciences Center-Shreveport (Louisiana), and housed in a specific pathogen-free environment. Male mice (10-12 weeks old) were used in this study. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

A mouse model of transient focal cerebral ischemia

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). Focal cerebral ischemia was induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) using a modification of the intraluminal filament method [16] with a 7-0 silicone-coated nylon monofilament (Doccol Corp). In ischemic groups, animals were subjected to MCAO for the indicated durations followed by reperfusion for the indicated times. In sham controls, the arteries were visualized but not disturbed. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37± 0.5°C during the surgical procedure and in the recovery period until the animals regained full consciousness with a feedback-regulated heating pad. Systemic parameters including pH and blood gases were all within normal range and there were no differences between wildtype and KO mice. Regional cerebral blood flow (CBF) was monitored by laser Doppler flowmetry (MSP300XP; ADInstruments Inc). Probes were placed at the center (from bregma: 3.5 mm lateral, 1.5 mm caudal) and periphery (from bregma: 1.5 mm lateral, 1.5 mm caudal) of the ischemic territory as previously described [17]. After transient ischemia, CBF was restored by withdrawal of the nylon suture. Only animals that exhibited a reduction in CBF>85% during MCAO and a CBF recovery by >80% after 15 min of reperfusion were included in the study.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized with overdose of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and intracardially perfused with 10 ml phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 20 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Following perfusion, brains were dissected and post-fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 4 h. After post-fixation, brains were transferred to 10-20-30% sucrose (w/v) in PBS until equilibrated. Brains were then frozen in OCT mounting medium, and 12 μm-thick coronal sections were collected between bregma -0.8 and 1.70 mm. Sections were subsequently mounted onto Poly-l-lysine-coated slides and allowed to air dry and stored in -80c until used. Three adjacent brain sections were collected at 600 μm intervals were processed for immunohistochemistry. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 10% normal serum and Avidin-blocking solution (Vector Laboratories). Sections were incubated with primary antibodies (diluted in 10% normal serum and biotin-blocking solution in PBS) at 4 °C overnight. Neutrophils were detected by rabbit anti-mouse PMN antibody (Accurate Chemical. 1:500). Endothelial cells were labeled by CD31 (1:100; BD Pharmingen). Microglia/macrophages were detected by two different markers [18,19], MAC-2 (Accurate chem. 1:500) and Iba-1(Wako, 1:1000). Neurons and astrocytes were detected using antibodies against neuronal-specific nuclear protein (NeuN, 1:1000; Millipore) and GFAP (1:500; Dako), respectively. The p110γ was detected by a polyclonal antibody against PI3-kinase p110γ (Cell Signaling, 1:500). The sections were then washed and incubated for 2 h with secondary antibodies with fluorescence conjugations. Irrelevant class- and species-matched immunoglobulins as well as incubations without the primary antibody were used as controls. For double-labeling immunofluorescence, after primary antibody incubation, sections were incubated with Alexa fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000 in PBS; Invitrogen). Images were taken using a Nikon fluorescence microscope equipped with FITC and rhodamine filter set. On each coronal section, the number of positively stained cells were counted from 8 randomly chosen regions within the cortex or striatum at × 200 magnification.

Cell cultures

Mouse brain cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in the recommended media. They include two cortical neurons (CRL-11179; CRL-10742), astrocytes (Astrocyte Type 1 clone, CRL-2541), microvascular endothelial cells (bEnd.3, CRL-2299), and microglia (EOC13.31,CRL-2468). In addition, two human brain cortical neurons (HCN-2, CRL-10742; HCN-1A, CRL-10442) were also tested. Subconfluent cultures (80-90%) were used for experiments.

Reverse Transcription-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from each hemisphere or cultured cells using an RNA isolation kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA. First strand cDNA was reverse transcribed from 1 μg total RNA with a Reverse Transcription System kit (Promega). The resulting cDNA (50 ng) was subjected to PCR amplification. Primers sequences were designed using PCR Primer Design Tools (Invitrogen) as follow: For p110γ (NM_001146201), 5'- ATATCTCAGAAAGTCAAAGT-3' (forward) and 5'-AGTAGATCTGTAGGTTCAAT-3' (reverse); for p84 (AY753194, ), 5'-ATAGAGCAGGTGGCTAGCGA-3' (forward) and 5'-TGCTTTCATACCATGGGTCGACTC-3' (forward); for p101 (NM_177320), 5′-AAGCCGGAGGAGCTAGACTC-3′(forward) and 5′-GCAGAGCCCCACTGAATGTC-3′ (reverse) ; and for GAPDH as internal control, ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC (forward) and TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA (reverse). Reactions were performed in 20 μl total volume by an initial cycle at 95°C for 4 minutes followed by 30 cycles for target genes or 20 cycles for GAPDH: 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s. The amplified products were separated on 1.5% agarose gels and images were scanned with a densitometer (GS-700, Bio-Rad Laboratories), and quantification was analyzed with Multi-Analyst 1.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Data were normalized to GAPDH in the same sample.

Western blot analysis

Each hemisphere was frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 2 ml of radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris·Cl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM NaF, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40) with freshly added protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The homogenate was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, CA). Equal amount of protein from each lysate was separated using 8% SDS-PAGE and the proteins transferred to nitrocellulose. The p110γ and p101 was detected as previously described [20], using rabbit polyclonal antibodies against PI3K p110γ (Cell Signaling, 1:1000) and p101 (PIK3R5) (LifeSpan Biosciences). Protein samples isolated from peritoneal leukocytes (PMN) of WT mice used as a positive control. Immunopositive bands of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were detected by ECL (GE Healthcare) and exposure to ECL Hyperfilm.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and Student's t-test. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

PI3Kγ is constitutively expressed in normal brain microvessels but upregulated in ischemia-activated microglia

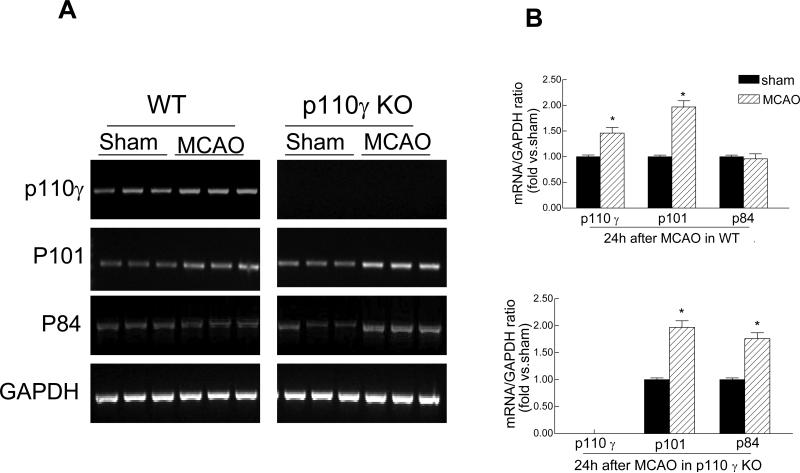

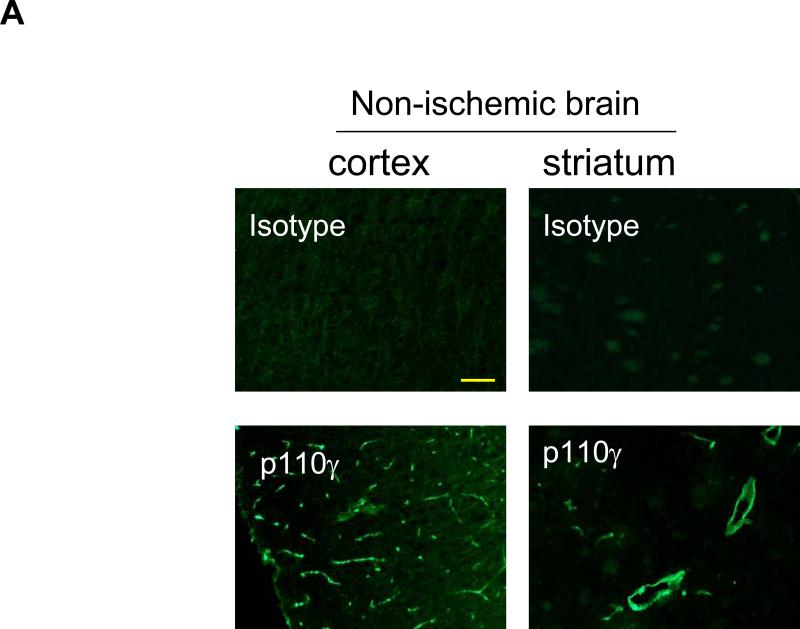

PI3Kγ is composed of a catalytic p110γ subunit and a regulatory p101 or p84/p87 subunit [7]. First, we examined and compared the expression of PI3Kγ in the normal and ischemic brains in wildtype (WT) and PI3K (p110γ) knockout (KO) mice. In WT mice, mRNA expression of all three subunits was easily detected by RT-PCR analysis in non-ischemic (sham) brains, and the p110γ and p101 mRNA was upregulated in ischemic brains 24h after MCAO (Fig. 1A, 1B). In p110γ KO mice, the p110γ mRNA was not detected in all brains as expected, however, somewhat surprisingly, we found that both regulatory p101 and p84 subunits were not only constitutively expressed, but was also upregulated in the ischemic p110γ-deficient brains (Fig 1A, 1B), suggesting that the expression of p101 and/or p84 in brain might have some unrecognized biological functions independent of p110γ. Consistent with the mRNA findings, the p110γ protein (~110 kDa) was detected by western blot analysis in non-ischemic brains and was upregulated (by ~45%) in ischemic brains in WT mice 24 h after MCAO, but as expected was absent in all KO brains (Fig. 1C, 1D). The regulatory subunit p101 was upregulated (~2-fold) in postischemic brains in both WT and KO mice (Fig. 1C, 1D).

Fig. 1.

Cerebral ischemia induces PI3Kγ expression in the brain. A, Reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of PI3Kγ subunits (p110γ, p101, p84) in sham-operated and ischemic hemispheres from wild-type (WT) and p110γ knockout (KO) mice 24 h after MCAO. Each lane represents a sample from an individual brain. B, Densitometric analysis of the band shown in A. Data represent mean ± SD from three separate experiments. *P<0.05 versus respective sham controls. C, Western blot analysis of protein expression of the p110γ and p101 in sham-operated and ischemic hemispheres in WT and KO mice. N=3 brain samples per lane. Protein samples extracted from peritoneal leukocytes (PMN) of WT mice used as a positive control. D, Densitometric analysis of the blot shown in C. Data represent mean ± SD from three separate experiments. *P<0.05 versus respective sham controls.

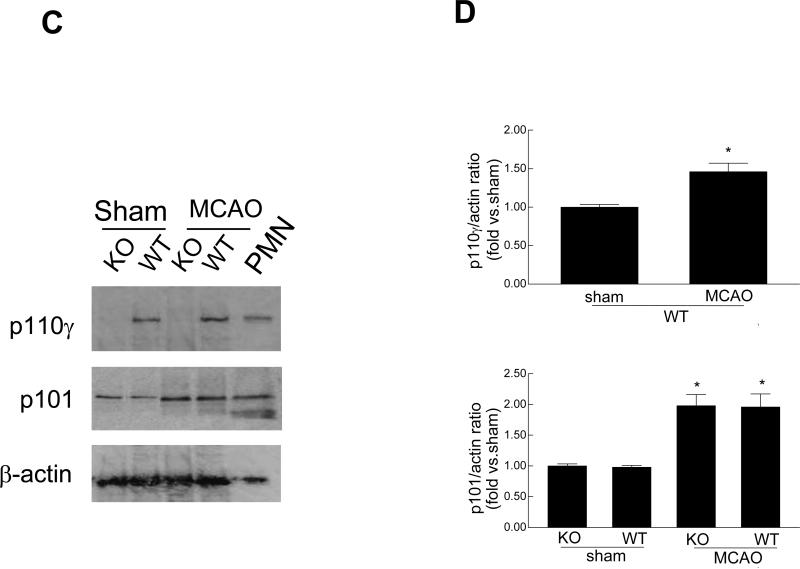

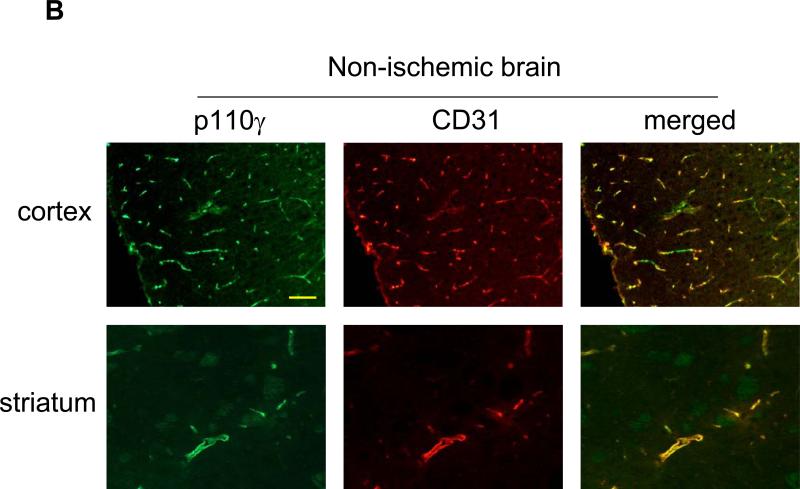

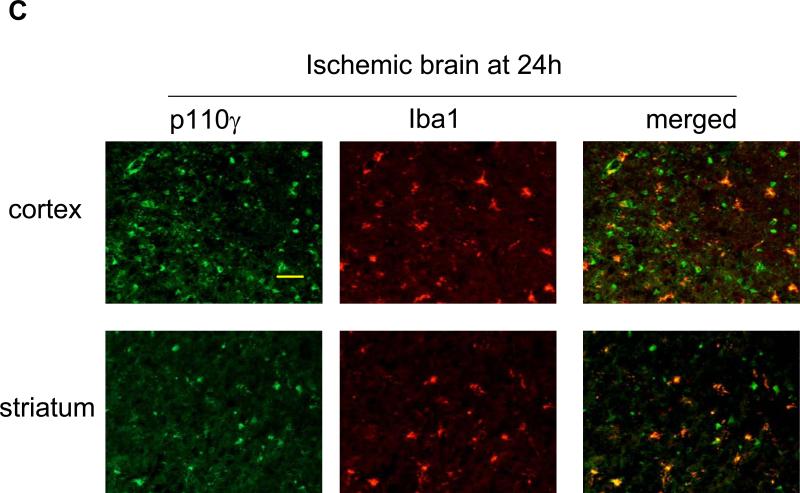

Subsequently, immunohistochemistry was used to determine the cellular sources of PI3Kγ in normal and ischemic brains. In WT mice, p110γ signals were primarily associated with vascular-like structures in the cortex and striatum (Fig. 2A), and double immunostaining indicates the endothelial origin of p110γ in normal brains (Fig. 2B). Further, data show that p110γ signals increased at 24h after MCAO and highly co-localized with Iba-1-positive microglia/macrophages in both postischemic cortex and striatum in WT mice (Fig. 2C). However, there was a lack of colocalization of the p110γ staining with either neuronal (NeuN) or astrocytic markers (GFAP) (data not shown). Collectively, our data demonstrate for the first time that the PI3Kγ is constitutively expressed in normal brain microvessels, and significantly upregulated in the postischemic brain primarily in microglia following cerebral ischemia.

Fig. 2.

PI3Kγ is elevated primarily in microglia in postischemic brain. A. Immunofluorescent staining of p110γ in the cortex and striatum regions in WT mice. In non-ischemic (sham) brains, PI3Kγ signals were primarily associated with vascular-like structures. B. Double staining showing co-localization of PI3Kγ signals with the endothelial marker CD31. C. In ischemic brains, PI3Kγ is upregulated 24h after MCAO and co-localized highly with Iba-1-positive activated microglia/macrophages. Bar=100 um.

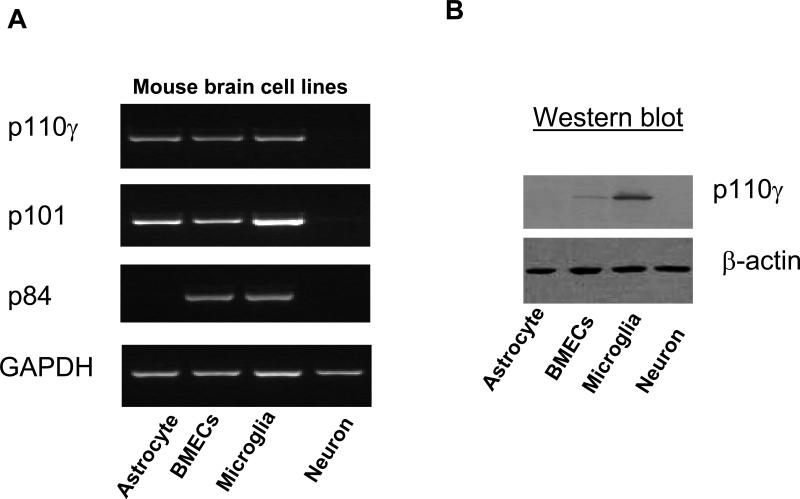

PI3Kγ is expressed in mouse brain microglial and endothelial cell lines

Further, the in vivo findings were verified by in vitro cell culture experiments. RT-PCR analysis shows that cultured murine brain microvascular ECs (bEnd.3) and microglia (EOC13.31) expressed all three subunits (Fig. 3A). Astrocytes (CRL-2541) expressed p110γ and p101 but not p84. Western blot analysis shows that the p110γ protein was detected in the ECs (bEnd.3) and more abundantly in the microglia (EOC13.31) (Fig. 3B). It has been reported that PI3K-p110γ was detected in the mouse brain neurons in the periaqueductal gray matter (PAG) [21] and in primary sympathetic and sensory neurons [22,23]. Although we cannot rule out low-level neuronal expression of PI3Kγ not detected by immunocytochemistry, our in vitro data show that the expression of p110γ along with p101 and p84 were very low or absent both in murine cortical neurons (Fig. 3A) and 2 human cortical neurons (CRL-10742; CRL-10442) (data not shown). Thus, PI3Kγ could be differentially expressed in neurons from different sources in the central nervous system.

Fig. 3.

Detection of PI3Kγ expression in mouse brain cell lines. A, Reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of PI3Kγ subunits (p110γ, p101, p84) in cultured murine brain cell lines. B, Western blot analysis of protein expression of p110γ in cultured murine brain cell lines. All experiments were repeated three times and yielded the same results.

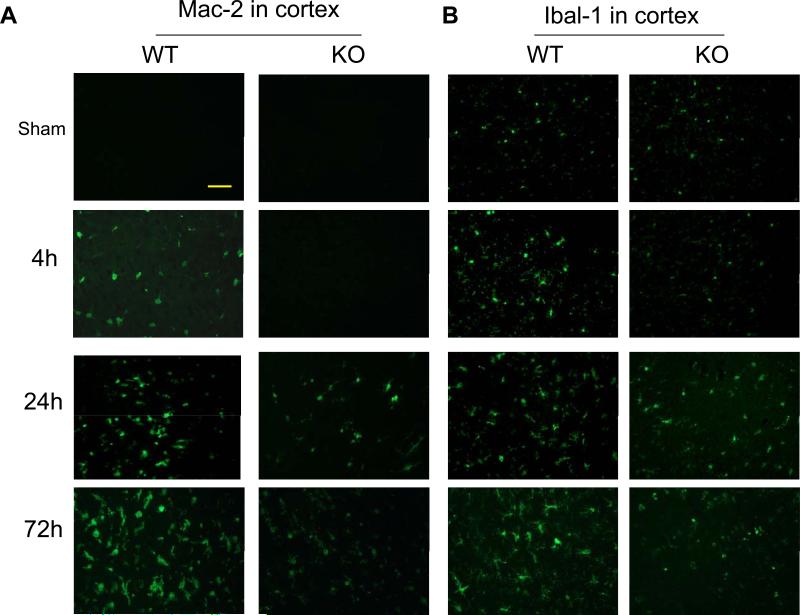

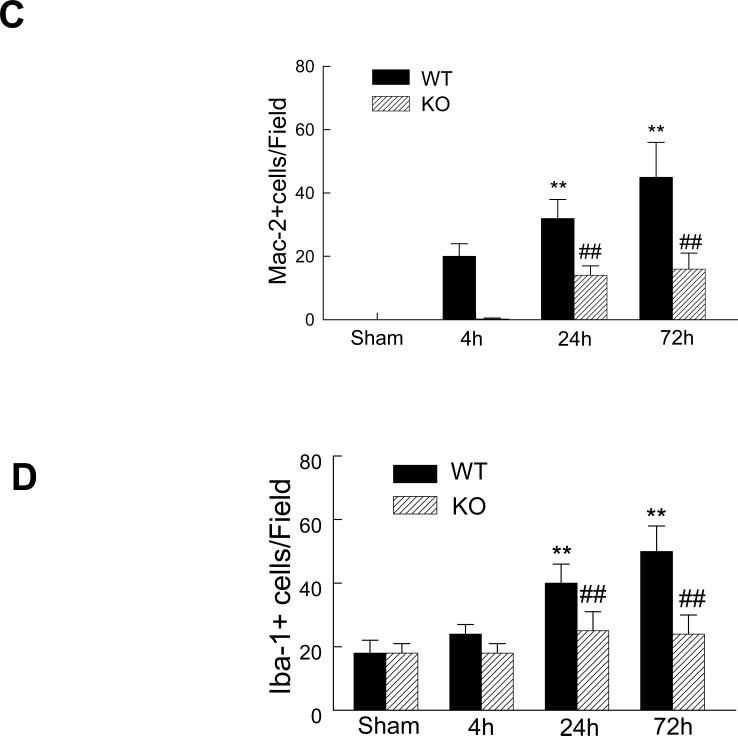

Absence of PI3Kγ inhibits ischemia-induced microglial activation and expansion

It has been reported that microglia, the resident macrophage of the brain, is rapidly activated and expanded after cerebral ischemia, but the mechanism regulating microglia activation/expansion is not understood. Therefore, we examined whether expression of PI3Kγ is involved in microglia activation and expansion after cerebral ischemia. We analyzed the microglial responses to cerebral ischemia using two different markers [18,19]: Mac-2, a marker of microglia/macrophages activation, and Iba1, a classic microglial marker. Mac-2 is preferentially expressed by resident microglia but not blood-derived macrophages in the brain within the first 72 h after focal cerebral ischemia [18]. As expected, in the sham-operated control brains, Mac-2-positive cells were not detected in both WT and PI3Kγ KO mice, but a few Iba1-positive cells were noted (Fig. 4A, 4B). In WT mice, Mac-2 staining reveals that microglia activation occurred as early as 4h and the number of Mac-2-positive cells significantly increased at 24 h and further increased at 72 h after MCAO (Fig. 4A, 4C). Iba-1 staining reveals that the number of the Iba-1-positive cells did not increase at 4h, but significantly increased at 24-72 h in WT mice (Fig. 4B, 4C). In KO mice, loss of PI3Kγ blocked the early microglia activation (at 4h) and subsequent expansion (at 24-72 h) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Absence of PI3Kγ reduces microglial activation and expansion in postischemic brain. Representative immunostaining pictures for Mac-2 (A) and Iba-1 (B) staining in the sham-operated and ischemic hemispheres at indicated times after MCAO. Bar= 50 um. Quantitative analysis of the number of cells positively stained for Mac-2 (C) and Iba-1 (D). n=5 mice per group. **P<0.01 versus the groups at 4h with the same genotype. ##P<0.01 versus respective WT groups at the same time points.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time that cerebral ischemia induces the expression of PI3Kγ in brain microglia and deficiency of PI3Kγ blocks the activation and expansion of microglia following acute experimental stroke in mice. Our data suggest that PI3Kγ is an ischemia-responsive gene in brain microglia and provide a novel reason to target microglia for treatment of cerebral ischemia.

Emerging evidence suggests that PI3Kγ is a key regulator of inflammation and implicates in inflammation-related diseases. Inhibition of PI3Kγ is expected to offer an innovative therapeutic strategy for inflammatory diseases [7]. Recent studies on PI3Kγ-deficient mice reveal that PI3Kγ regulates some crucial inflammatory and immune function including the chemotaxis, proliferation and cytokine production of leukocyte [5-7]. It has been reported that PI3Kγ-deficient mice display in vitro and in vivo impaired migration of neutrophils and macrophages towards chemoattractants [5,15]. Similarly, pharmacological blockage of PI3Kγ by the selective inhibitor AS605240 is an effective treatment in murine models of rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and atherosclerosis via inhibiting the recruitment of inflammatory cells and suppressing the progression of inflammation [24-25]. Conversely, the role of PI3Kγ in stroke and other neurovascular disorders is unknown.

Although the expression of PI3Kγ has been described in leukocytes and in several cardiovascular tissues, the expression, tissue distribution, and cellular localization of PI3Kγ in the central nervous system under physiological and pathophysiological conditions remain largely unknown. One finding from our study is that PI3Kγ is constitutively and abundantly expressed in normal brain tissues, almost exclusively associated with microvascular-like structures in the cortex and striatum, indicating the endothelial origin of PI3Kγ. In contrast, the present data show that the expression of PI3Kγ is not detected in other types of brain cells including neuron and microglia in the cortex and striatum. Another finding from our study is that PI3Kγ expression is upregulated in the brain primarily in activated microglia in the early phase (within 24 h) after focal cerebral ischemia. Finally, the most important finding in our study is that absence of PI3Kγ blocks brain microglial activation and expansion after cerebral ischemia. Microglia can be activated rapidly (within a few hours) and then expanded by proliferation usually peaking 48–72 h after cerebral ischemia [1, 27]. Although microglia and macrophages are indistinguishable morphologically, several elegant studies [28, 29] by Schilling et al. using green fluorescent protein transgenic bone marrow chimeric mice have definitely demonstrated that resident microglia are activated rapidly within 24 h and predominates over blood-derived macrophage infiltration within 72 h after transient focal cerebral ischemia. The present data show that microglia is activated as early as 4 h and expanded significantly at 24 and 72 h after focal cerebral ischemia. However, the early activation (4 h) and subsequent expansion (24-72 h) was greatly inhibited in PI3Kγ-deficient mice. These findings suggest that microglial activation and expansion after cerebral ischemia is mediated through a PI3Kγ-dependent mechanism.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL087990 (G.L.) and by a scientist development grant (0530166N, G.L.) from the American Heart Association.

References

- 1.Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010;87:779–789. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1109766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoll G, Jander S. The role of microglia and macrophages in the pathophysiology of the CNS. Prog. Neurobiol. 1999;58:233–247. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinstein JR, Koerner IP, Möller T. Microglia in ischemic brain injury. Future Neurol. 2010;5:227–246. doi: 10.2217/fnl.10.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yenari MA, Xu L, Tang XN, Qiao Y, Giffard RG. Microglia potentiate damage to blood-brain barrier constituents: improvement by minocycline in vivo and in vitro. Stroke. 2006;37:1087–1093. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206281.77178.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch E, Katanaev VL, Garlanda C, Azzolino O, Pirola L, Mantovani A, Altruda F, Wymann MP. Central role for G protein-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ in inflammation. Science. 2000;287:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puri KD, Doggett TA, Huang CY, Hayflick JS, Turner M, Penninger J, Diacovo TG. The role of endothelial PI3Kgamma activity in neutrophil trafficking. Blood. 2005;106:150–157. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghigo A, Damilano F, Braccini L, Hirsch E. PI3K inhibition in inflammation: Toward tailored therapies for specific diseases. Bioessays. 2010;32:185–196. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frey RS, Gao X, Javaid K, Siddiqui SS, Rahman A, Malik AB. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma signaling through protein kinase Czeta induces NADPH oxidase-mediated oxidant generation and NF-kB activation in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:16128–16138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang J, Upadhyay UM, Tamargo RJ. Inflammation in stroke and focal cerebral ischemia. Surg. Neurol. 2006;66:232–245. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denes A, Thornton P, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Inflammation and brain injury: Acute cerebral ischaemia, peripheral and central inflammation. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2009;24:708–723. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uno M, Harada M, Takimoto O, Kitazato KT, Morita N, Itabe H, Nagahiro S. Elevation of plasma oxidized LDL in acute stroke patients is associated with ischemic lesions depicted by DWI and predictive of infarct enlargement. Neurol. Res. 2005;27:94–102. doi: 10.1179/016164105X18395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheehan JJ, Tsirka SE. Fibrin-modifying serine proteases thrombin, tPA, and plasmin in ischemic stroke: a review. Glia. 2005;50:340–350. doi: 10.1002/glia.20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edvinsson L. Cerebrovascular angiotensin AT1 receptor regulation in cerebral ischemia. Trends. Cardiovasc. Med. 2008;18:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chrysant SG. The pathophysiologic role of the brain renin-angiotensin system in stroke protection: clinical implications. J. Clin. Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9:454–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki T, Irie-Sasaki J, Jones RG. Function of PI3Kγ in thymocyte development, T cell activation, and neutrophil migration. Science. 2000;287:1040–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terao S, Yilmaz G, Stokes KY, Russell J, Ishikawa M, Kawase T, Granger DN. Blood cell-derived RANTES mediates cerebral microvascular dysfunction, inflammation, and tissue injury after focal ischemia-reperfusion. Stroke. 39(2008):2560–2570. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin G, Tsuji K, Xing C, Yang YG, Wang X, Lo EH. CD47 gene knockout protects against transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Exp. Neurol. 217(2009):165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lalancette-Hébert M, Gowing G, Simard A, Weng YC, Kriz J. Selective ablation of proliferating microglial cells exacerbates ischemic injury in the brain. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2596–2605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5360-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka R, Komine-Kobayashi M, Mochizuki H, Mizuno T, Urabe T. Migration of enhanced green fluorescent protein expressing bone marrow-derived microglia/macrophage into the mouse brain following permanent focal ischemia. Neuroscience. 2003;117:531–539. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00954-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puri KD, Doggett TA, Huang CY, Turner M, Penninger J, Diacovo TG. The role of endothelial PI3Kgamma activity in neutrophil trafficking. Blood. 2005;106:150–157. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narita M, Imai S, Narita M, Kasukawa A, Yajima Y, Suzuki T. Increased level of neuronal phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma by the activation of mu-opioid receptor in the mouse periaqueductal gray matter: further evidence for the implication in morphine-induced antinociception. Neuroscience. 2004;124:515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartlett SE, Reynolds AJ, Tan T, Heydon K, Hendry IA. Differential mRNA expression and subcellular locations of PI3-kinase isoforms in sympathetic and sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;56:44–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990401)56:1<44::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.May V, Lutz E, MacKenzie C, Schutz KC, Dozark K, braas BKM. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)/PAC1HOP1 receptor activation coordinates multiple neurotrophic signaling pathways: Akt activation through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma and vesicle endocytosis for neuronal survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:9749–9761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.043117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barber DF, Bartolome A, Hernandez C, Flores JM, Redondo C, Ruckle T, Schwarz MK, Rodriguez S, Martinez AC, Rommel C, Carrera AC. PI3Kgamma inhibition blocks glomerulonephritis and extends lifespan in a mouse model of systemic lupus. Nat. Med. 2005;11:933–935. doi: 10.1038/nm1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camps M, Ruckle T, Ji H, Ardissone V, Rintelen F, Shaw J, Ferrandi C, Chabert C, Gillieron C, Francon B, Gretener T, Hirsch E, Wymann MP, Cirillo R, Schwarz MK, Rommel C. Blockade of PI3Kgamma suppresses joint inflammation and damage in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Med. 2005;11:936–943. doi: 10.1038/nm1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fougerat A, Gayral S, Gourdy P, Schwarz MK, Hirsch E, Perret MP. Wymann and M. Laffargue, Genetic and pharmacological targeting of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-gamma reduces atherosclerosis and favors plaque stability by modulating inflammatory processes. Circulation. 2008;117:1310–1317. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.720466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denes A, Vidyasagar R, Feng J, Narvainen J, McColl BW, Kauppinen RA, Allan SM. Proliferating resident microglia after focal cerebral ischaemia in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1941–1953. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schilling M, Besselmann M, Leonhard C, Ringelstein EB, Kiefer R. Microglial activation precedes and predominates over macrophage infiltration in transient focal cerebral ischemia: a study in green fluorescent protein transgenic bone marrow chimeric mice. Exp. Neurol. 2003;183:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schilling M, Besselmann M, Müller M, Strecker JK, Ringelstein EB, Kiefer R. Predominant phagocytic activity of resident microglia over hematogenous macrophages following transient focal cerebral ischemia: an investigation using green fluorescent protein transgenic bone marrow chimeric mice. Exp. Neurol. 2005;196:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]