Abstract

Schizophrenic patients are heterogeneous with respect to voluntary eye movement performance, with some showing impairment (e.g., high antisaccade error rates) and others having intact performance. To investigate how this heterogeneity may correlate with different cognitive outcomes after treatment, we used a prosaccade and antisaccade task to investigate the effects of haloperidol in schizophrenic subjects at three time points: baseline (before medication), 3–5 days post-medication, and 12–14 days post-medication. We also investigated changes on the Stroop Task and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) in these same subjects. Results were compared to matched controls. When considered as a single patient group, haloperidol had no effects across sessions on reflexive and voluntary saccadic eye movements of schizophrenic patients. In contrast, the performance of the Control group improved slightly but significantly across sessions on the voluntary eye movement task. When each subject was considered separately, interestingly, for schizophrenic patients change in voluntary eye movement performance across sessions depended on the baseline performance in a non-monotonic manner. That is, there was maximal worsening of voluntary eye movement performance at an intermediate level of baseline performance and the worsening decreased on either side of this intermediate baseline level. When patients were divided into categorical subgroups (nonimpaired and impaired), consistent with the non-monotonic relationship, haloperidol worsened voluntary eye movement performance in the nonimpaired patients and improved performance in the impaired patients. These results were only partially reflected in the Stroop Test. Both patient subgroups showed clinically significant improvement over time as measured by the PANSS. These findings suggest that haloperidol has different effects on cognitive performance in impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenic patients that are not evident in clinical ratings based on the PANSS. Given that good cognitive function is important for long-term prognosis and that there is heterogeneity in schizophrenia, these findings are critical for optimal evaluation and treatment of schizophrenic patients.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Cognitive control, Saccades, Typical antipsychotic, Neuropsychological test

1. INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is the most chronic, debilitating, and costly mental disorder, affecting approximately 1% of the world’s population. In the United States alone, the average cost of schizophrenia in 2002 was estimated to be over 60 billion dollars a year, (Wu, et al., 2005) accounting for one fourth of all mental health costs. Pharmacological treatments of schizophrenia patients have been partially successful, with a recent study demonstrating remission of psychotic symptoms in about 90% first-episode patients (Robinson, et al., 1999). However, alleviation of psychotic symptoms does not predict long-term outcome, with an estimated relapse rate as high as 80% within 2 years (Hogarty & Ulrich, 1998). Some studies have shown that cognitive impairments are more strongly related to functional outcome than to other aspects of the illness, such as positive symptom severity (Green, 1996; Harvey, et al., 1998; Meltzer & McGurk, 1999; Velligan, et al., 2002). That is, executive functions, such as attention and working memory, are the measures that most strongly predict school and occupational functioning, social functioning, and ability to complete activities of daily living.

For these and other reasons, there has been a broadening and change in perspective by some clinicians in both defining and measuring clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia (Kern, Glynn, Horan, & Marder, 2009; Nasrallah, Targum, Tandon, McCombs, & Ross, 2005). Thus, there is a need for simple, objective, and quantifiable methodologies that can better define cognitive neuropathology and subtle cognitive deficits at an individual level. Besides the importance of cognitive abilities in more favorable outcome, there is recent recognition of the variability in drug response (e.g. Riccardi, et al., 2006) and the importance of individualized clinical treatment (for review, Eichelbaum, Ingelman-Sundberg, & Evans, 2006).

For over 50 years typical antipsychotic medications have been used to treat schizophrenic psychosis. The clinically efficacy of these drugs is thought to be due to blockage of D2 receptors in the mesolimbic pathway. However, these medications concomitantly further reduce dopamine in the already hypodopaminergic frontal cortex and decrease the expression of D1 receptors in the prefrontal cortex (Lidow, Elsworth, & Goldman-Rakic, 1997; Lidow & Goldman-Rakic, 1994), which are critical for proper executive functions, such as attention (Chudasama & Robbins, 2004; Granon, et al., 2000) and working memory (Brozoski, Brown, Rosvold, & Goldman, 1979; Goldman-Rakic, 1991; Sawaguchi & Goldman-Rakic, 1991; Williams & Goldman-Rakic, 1995). This “side effect” of typical medications may contribute to some of the detrimental effects of typical antipsychotics on cognition (Lustig & Meck, 2005; Mortimer, 1997; Purdon, Malla, Labelle, & Lit, 2001; Saeedi, Remington, & Christensen, 2006; Seidman, et al., 1993; Sweeney, et al., 1997; Verdoux, Magnin, & Bourgeois, 1995). Some studies, however, have shown improved cognition secondary to drug treatment (Cassens, Inglis, Appelbaum, & Gutheil, 1990; Cleghorn, Kaplan, Szechtman, Szechtman, & Brown, 1990; Harvey, Rabinowitz, Eerdekens, & Davidson, 2005; Keefe, et al., 2006; Mishara & Goldberg, 2004; Pigache, 1993; Remillard, Pourcher, & Cohen, 2005).

Previous studies investigating the cognitive effects of typical antipsychotics usually have used a variety of neuropsychological tasks: tests of frontal lobe functions, working memory, inhibition, and decision making. Although useful, neuropsychological tasks are often complex, time consuming, and susceptible to practice effects, making it difficult to evaluate small, yet meaningful, performance changes due to medication at multiple time points. In contrast, eye movements are well understood and simpler than standard neuropsychological tests that often require language and/or object or scene processing skills.

Eye movements have often been used, even at an individual level, to test distributed brain systems involved in sensorimotor and cognitive processes and to elucidate in clinical populations whether these systems are normal or dysfunctional (Leigh & Kennard, 2004; Munoz & Everling, 2004; Sereno, Briand, Amador, & Szapiel, 2006; Sweeney, Levy, & Harris, 2002). Saccadic eye movements have become an increasingly popular tool for investigating frontal lobe functioning, and voluntary saccadic eye movement deficits have even been proposed as a potential schizophrenia endophenotype (Hutton & Ettinger, 2006; Radant, et al., 2007; Waterworth, Bassett, & Brzustowicz, 2002). Eye movement measures provide objective neurobehavioral evidence (Gooding & Basso, 2008) and show sensitivity at an individual level (Sereno, et al., 2006), reliability at an individual level (Ettinger, et al., 2003; Gooding, Mohapatra, & Shea, 2004), specificity with respect to brain regions (e.g., (Guitton, Buchtel, & Douglas, 1985; Pierrot-Deseilligny, Muri, Nyffeler, & Milea, 2005; Ploner, Gaymard, Rivaud-Pechoux, & Pierrot-Deseilligny, 2005), and their use has been suggested to be helpful in individualizing pharmacological treatments (Reilly, Lencer, Bishop, Keedy, & Sweeney, 2008). The study of saccades also provides a unique opportunity to study reflexive processes (e.g., as measured in a prosaccade task: look toward a target) and voluntary processes (e.g., as measured in an antisaccade task: look away from the target) separately. By measuring and comparing performance on these tasks, we can separate medication effects on basic sensory processing of the target and final common motor output pathways (observed as changes on both the prosaccade and antisaccade tasks) from medication effects on cognitive, prefrontal-cortex-mediated, higher-order processing (observed as changes only in the antisaccade task) (Funahashi, Bruce, & Goldman-Rakic, 1991; Guitton, et al., 1985; Sereno, 1996).

To date, five studies have specifically investigated the effects of typical antipsychotic medications on voluntary saccadic eye movements in schizophrenia (see Table 1). One study showed a significant improvement (decrease) in error rate and another study showed a significant decrease in voluntary saccade latency (response time) secondary to treatment with typical antipsychotic medication (Harris, Reilly, Keshavan, & Sweeney, 2006; Hutton, et al., 1998). Decisive conclusions cannot be drawn, however, because of certain methodological differences among the studies. Of particular importance, only two of these five studies tested the effects of a single typical antipsychotic medication (haloperidol) (Cassady, Thaker, & Tamminga, 1993; Harris, et al., 2006) on voluntary saccadic eye movements, whereas the other three studies examined the effects of a mixture of typical antipsychotics (Crawford, Haeger, Kennard, Reveley, & Henderson, 1995; Muller, Riedel, Eggert, & Straube, 1999) or did not report the specific medications (Hutton, et al., 1998).

Table 1.

Summary of Studies on the Effects of Typical Antipsychotics on Voluntary Eye Movements

| Cassady et al (1993) | Crawford et al (1995) | Hutton et al (1998) | Muller et al (1999) | Harris et al (2006) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error Rate (%) | No Change | No Change | No Change | No Change | Decrease |

| Response Time (ms) | No Change | Decrease | No Change | No Change | |

| Medication Type | Haloperidol | Mixed | Unkown | Mixed | Haloperidol |

| Chlorpromazine Equivalentsa | Low to High | High | Unknown | Low | Low |

| Study Design | Within | Between | Between | Within | Within |

| Schizophrenic Population | Outpatients | Unknown | Unknown | Inpatients/Outpatients | Inpatients/Outpatients |

>1000mg=High and <1000mg=Low

A second factor that complicates the interpretation of these studies is the large variability in medication dosages in the three studies reporting significant medication effects. Specifically, one study showed cognitive benefit (improved voluntary saccade performance) with a low dose of haloperidol (3.8 mg on average (Harris, et al., 2006)), a second study showed cognitive impairment (worsening voluntary saccade performance) with a high dose of haloperidol (32 mg on average (Crawford, et al., 1995)), and the third study did not report medication dosage (Hutton, et al., 1998). These results are consistent with some studies showing optimal clinical improvement with haloperidol doses between 6 mg and 12 mg (with no statistical benefit of higher doses) (Geddes, Freemantle, Harrison, & Bebbington, 2000) and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia patients with haloperidol doses over 24 mg (Woodward, Purdon, Meltzer, & Zald, 2007). Finally, some studies involved between group comparisons of medicated versus unmedicated patients (Crawford, et al., 1995; Hutton, et al., 1998). Thus, patients in the medicated groups in these studies have no measure of eye movement performance when they were unmedicated. Schizophrenia patients are heterogenous with respect to eye movement performance with typically about 50–85%, of schizophrenia subjects showing impairments ((Holzman, Proctor, & Hughes, 1973; Holzman, et al., 1974; Sereno & Holzman, 1995; Zanelli, et al., 2005). Given that only about 60% of schizophrenia patients show impaired performance on the antisaccade task (Fukushima, et al., 1988; Larrison-Faucher, Matorin, & Sereno, 2004) and that this subgroup can respond differently to substances such as nicotine (Larrison-Faucher, et al., 2004), it is possible that results from between group comparisons were due to baseline differences between the medicated groups rather than to medication differences. Only a longitudinal design involving repeated measures on the same individuals in unmedicated and medicated states can resolve this ambiguity.

In the present study, we investigated the effects of 15 mg of haloperidol (see Table 2 for exceptions) on reflexive and voluntary saccadic eye movements. We tested the same schizophrenia inpatients prior to treatment with antipsychotic medication and at two time points while medicated to better capture longitudinal effects of medication on these eye movement tasks. Using both reflexive and voluntary tasks is necessary for accurately distinguishing haloperidol’s effects on sensory and motor processing from its effects on higher order cognitive processing. Additionally, due to the previously described heterogeneity among schizophrenia patients (Bechard-Evans, Iyer, Lepage, Joober, & Malla; Gonzalez-Blanch, et al., 2010; Levy, Holzman, Matthysse, & Mendell, 1994; Ross, 2000) we examined the relationship between baseline antisaccade performance and the change in antisaccade performance across sessions. Further, we also divided the schizophrenia subjects into “impaired” and “nonimpaired” categorical subtypes based on baseline antisaccade performance. Finally, we conducted the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, (Kay, Fiszbein, & Opler, 1987) and the Stroop Task (Stroop, 1935) on these same patients to compare performance on these standard clinical and neuropsychological scales with performance on the eye movement tasks.

Table 2.

Medications of schizophrenia patients. All dosages are per day. The psychotropic medications are shown in bold. H: 15 mg haloperidol, H-10: 10 mg haloperidol, H-20: 20 mg haloperidol, F: 50 mg fluphenazine, R: 4 mg risperidone, Lo: 2 mg lorazepam given on prior day, B: 4 mg benzatropine, B-2: 2 mg benzatropine, M: metformin, E: 5 mg enalapril, Li: lisinopril, Ht: hydrochlorothiazide, D: diphenhydramine, A: acetaminophen.

| Subjects | Age | Medications | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day s | Day l | ||

| Patients | ||||

| Non-Impaired | ||||

| 1 | 24 | H-10, B | Same as Day s | |

| 2 | 49 | Ht, E | H-20, B, Ht, E | H-20, B |

| 3 | 58 | M | H-10, B, Ht | H, B, Ht, M |

| Impaired | ||||

| 1 | 23 | H, B, Lo | H, B | |

| 2 | 24 | H, B | Same as Day s | |

| 3 | 24 | H, R, B-2, D | H, B | Same as Day s |

| 4 | 26 | H, B | Same as Day s | |

| 5 | 29 | H, B | Same as Day s | |

| 6 | 33 | H, B | Same as Day s | |

| 7 | 33 | H-10, B-2 | F, B, D | F, B, A |

| 8 | 37 | H, B | Same as Day s | |

| 9 | 47 | H, B | Same as Day s | |

| 10 | 51 | M | H, B, M, Li, A | H, B, M, Li, Ht |

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject Demographics and Recruitment

Schizophrenia patients were recruited from the University of Texas Harris County Psychiatric Hospital, Houston, Texas. All the testing on schizophrenia patients was performed while they were inpatients in the hospital. Thirteen schizophrenia and 10 control subjects participated. All subjects had normal or corrected to normal visual acuity.

Table 3 shows the demographic data for each group including age, education, handedness, smoking, gender, and age of onset and duration for the patient group and subgroups. Of note, the schizophrenia group and the control group differed only in smoking (χ2 = 7.8, p < 0.01) and gender (χ2 = 12.6, p < 0.01). However, neither schizophrenia nor control subjects were allowed to smoke within two hours of the start of any testing session. Additionally, in our data, there were no correlations between gender and any of the eye movement measures in the schizophrenia and control groups.

Table 3.

Demographic data for all Schizophrenic and Control Subjects

| Schizophrenia (n=13) | Impaired (n=6) | Nonimpaired (n=7) | Impaired (n=10) | Nonimpaired (n=3) | Control (n=10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Split | SD Split | |||||

| Agea | 35.2 (12.1) | 32.2+ (9.0) | 37.9 (14.4) | 32.7 (9.8) | 43.7 (17.6) | 38.2 (7.2) |

| Educationa | 11.9 (2.5) | 10.8* (2.1) | 12.9 (2.6) | 11.8 (2.7) | 12.3 (2.5) | 12.4 (1.2) |

| Handedness | 10R/2L/1B | 4R/1L/1B | 6R/1L/0B | 7R/2L/1B | 3R/0L/0B | 9R/1L/0B |

| Smoking | 9Y/4N** | 5Y/1N** | 4Y/3N** | 7Y/3N** | 2Y/1N** | 4Y/6N |

| Gender | 9M/4F** | 5M/1F** | 4M/3F** | 7M/3F** | 2M/1F** | 2M/8F |

| Age of Onseta | 26.2 (8.9)b | 25.3 (9.8) | 27.4 (8.1) | 26.4 (9.8) | 26.0(1.4)b | -- |

| Durationa | 7.2 (7.6)b | 6.8 (7) | 10.4 (11.2) | 5.0 (4.7) | 11.5 (16.3)b | -- |

Age, education, age of onset, and duration of disease in years (standard deviation)

Age of onset and duration data are missing for one subject

Comparison to Controls:

p<0.01;

p<0.05;

p<0.10

The diagnosis of schizophrenia was made by a board certified psychiatrist using the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV). Patients and controls were excluded from our study if they had a history of Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, autism, severe head trauma, or any current substance abuse/dependence. In addition to these exclusion criteria, controls had no previous history of psychosis and had no first-degree relatives with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or autism. All schizophrenia patients were off psychotropic medications for at least three weeks prior to enrollment in this study (see Table 2 for exceptions where they had received one dose before baseline testing). All study participants gave informed consent at the start of each testing session, which was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and Harris Country Psychiatric Center and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Apparatus

Saccadic eye movements were recorded using an infrared ISCAN RK-826 PCI eye tracking system. Subjects were seated in front of a 17-inch CRT monitor with their heads placed in a stable chin rest that was positioned 72 cm from the screen. The spatial and temporal resolutions of the eye tracker were approximately 0.5° visual angle and 4 ms (240 Hz), respectively. Before the start of an eye movement recording session, the subject was calibrated by moving their eyes to nine positions on the screen indicated by 0.2° × 0.2° white boxes on a black background. For the eye movement tasks, a gray fixation dot of 0.2° was illuminated in the center of the black screen. Target stimuli were 0.2° × 0.2° white boxes that appeared 7° to the right and left of the fixation point. Saccade initiation and termination were defined by areal and velocity criteria. Specifically, for saccade initiation, eye velocity had to be above 47.5°/sec and for saccade termination, eye velocity had to be both below 12°/sec and within 4.4° of the target.

Procedure

Prosaccade and antisaccade tasks were administered to all schizophrenia patients at three different time points: prior to starting daily medications (baseline), 3–5 days after initiation of medication (short-term), and after 12–14 days of medication exposure (long-term; the average length of stay for an inpatient at Harris Country Psychiatric Center). The medications for each schizophrenia patient are reported in Table 2. Controls were not given medication and were tested at the same three intervals for comparison. Upon completion, the prosaccade and antisaccade tasks each yielded a block of 48 trials. Trials interrupted by a blink were aborted and randomly re-presented. To familiarize the subject with the task, each task was preceded by a 10-trial practice block. To further ensure that the task instructions were properly understood, each subject verbally repeated the instructions before each task began. For each task, target position was balanced for presentation in the left or right visual field. To begin a trial, the subject had to fixate a point located straight ahead for 600 ms. After this fixation period, the target randomly appeared 7° to the left or right of the fixation point. For the prosaccade task, the subject had to look at the peripheral target, while for the antisaccade task the subject had to look to the opposite side or mirror image location of the peripheral target. For both tasks, visual but no auditory feedback for incorrect eye movements was provided to the subjects after each trial regarding their performance. The peripheral target remained on the screen until the eye movement was completed.

Clinical and Neuropsychological Test Administration

Stroop Task

The Stroop Task is a common neuropsychological test used to evaluate frontal lobe processing and attention in subject groups. The “Naming Colored Words” version was used in this experiment. This version of the Stroop has three parts (Word, Color and Word-Color interference), each requiring the subject to name as many items (word in Word portion, color in Color portion and color of the ink in which word is written in Word-Color interference portion) as possible from a list in 45 seconds. The number of items named in 45 seconds for each of the three subscale parts is the reported score for each subject.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is a 30-item rating instrument that assessed positive, negative, and general psychopathology in schizophrenia patients within 24 hours of each of the three eye movement testing sessions. A higher PANSS score indicates worse clinical symptomatology. Each item was rated from 1 (absent) to 7 (severe). The rater was blind to the eye movement data. The PANSS was administered to schizophrenia subjects only.

Statistical Analyses

Calculation of latency

Saccade eye movement latencies (or response time) were trimmed at 2.5 standard deviations around the mean. This trimming was performed separately for each subject (schizophrenia, control), task (saccade, antisaccade) and session (baseline, short, long). The percentage of outliers that exceeded these criteria for latencies of prosaccades was 5.0% and 1.8% and antisaccades, 6.5% and 1.7% (for schizophrenia subjects and controls, respectively). Only data from correct trials were used. After the above procedures, mean latencies were computed for each subject by averaging remaining responses within each condition (including session, task, and visual field).

Calculation of error rate

Direction errors were defined as eye movements that looked away from the target (prosaccade task) or toward the target (antisaccade task). At each testing time point (baseline, short-term, or long-term) and for each task type (prosaccade or antisaccade), the error rate was calculated by dividing the number of incorrect trials by the total number of trials (i.e. 48) completed for each task. A higher error rate indicates poorer performance.

Comparison of Schizophrenia and Control groups

A three-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Group (schizophrenia/control) as the between-group factor and Task (prosaccade/antisaccade) and Session (baseline/short/long) as the within-groups factors was used to analyze the mean latency and error rate. The p-values reported here are based on Greenhouse-Geisser correction. The distribution of antisaccade error rate data across subjects (control and schizophrenia) for each time point was normal (Lilliefors test). However, the distribution of saccade error rate across subjects (control and schizophrenia) for each time point was not normal because there were many data points that were zero. Hence, we also ran non-parametric analyses (Wilcoxon) for saccade error rate data. There were no differences between the parametric and non-parametric analyses of saccade error rate. Hence, for consistency with prior reports and the analyses of other dependent measures, we report the parametric analyses.

A similar three-way repeated measures ANOVA was also run for mean Stroop Test scores, however the Session factor only had two time points (baseline/long) and the Task factor had three levels (Word/Color/Word-Color). A one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Session (baseline/short/long) as the within-group factor was used to analyze the mean Total PANSS scores within the schizophrenia group. For all these ANOVAs, we only report significant (p < 0.05) main and interaction effects.

In addition planned t-tests were conducted for prosaccade and antisaccade tasks using the mean squared error value for the appropriate term in the ANOVA. Comparisons included the following: (1) between the two groups, (2) across testing sessions (baseline to long), and (3) between groups across testing sessions. The t-statistic for two given conditions, 1 and 2, was computed as follows:

where, μ1, μ2, N1, and N2 are the means and the number of samples in condition 1 and condition 2 respectively. MSEANOVA is the mean square error for the appropriate term in the ANOVA. In the Results section, only the planned comparisons that had p-values less than 0.05 are discussed. Again there were no differences with the non-parametric comparisons for saccade error rate.

Antisaccade error rate change across sessions versus baseline error rate

The previous analysis was based on group averages and it does not consider the baseline differences on an individual basis. As mentioned earlier, understanding individual differences is critical for individualized treatment. To consider each subject’s baseline performance seperately, antisaccade error rate data were analyzed using regression analyses with the subjects’ baseline error rate as the independent variable and the change in error rate across testing sessions (long – baseline) as the dependant variable. Two regression analyses were performed: 1. Regression lines were fit to the data from all the schizophrenia subjects and controls and the slopes of the regression fits of schizophrenia subjects were compared to those of controls. The comparison between the regression slopes of schizophrenia subjects and controls was performed non-parametrically using a standard boot-strapping method. 2. A non-linear regression was perfomed to fit a Gaussian function described below:

In this Gaussian model, parameters y and x are antisaccade error rate and baseline error rate, respectively. β is the baseline error rate corresponding to the peak of the Gaussian σ function. σ is the standard deviation of the Gaussian function. A is the amplitude of the Gaussian function and B is the change in error rate across sessions (long – baseline) which is independent of the baseline error rate. Bootstrapping was performed to determine the confidence intervals for all the parameters of the Gaussian function. The Gaussian model would be considered significant if the confidence intervals of A and σ did not include zero. For comparison of the Gaussian fit to the linear fit, adjusted R2 was computed for both fits ( , where R2, n and k are the coefficient of determination, number of observations, and number of model parameters respectively). Adjusted R2 takes into account the cost associated with increasing the number of parameters in a model and is therefore better suited than the unadjusted values of R2 for comparing models with unequal numbers of parameters.

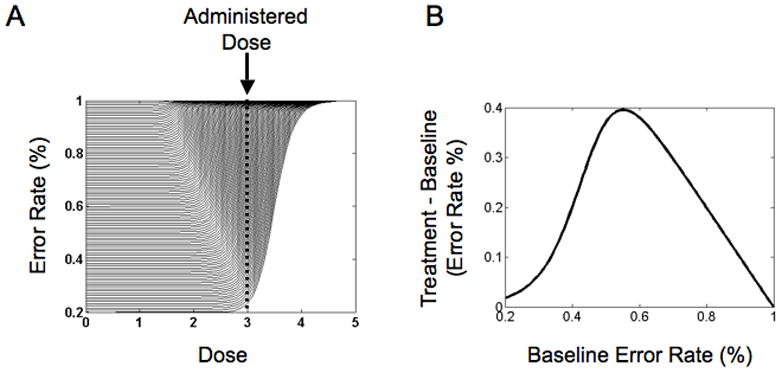

A sigmoid function is common in drug response profiles. If the sigmoidal drug response profiles are different for individual subjects who have different baseline responses (see Figure 1A), then a non-monotonic Gaussian type relationship between baseline response and change in response from baseline is possible (see Figure 1B). It should be noted that an antagonistic dose-response curve was used in our example to illustrate how a non-monotonic dose-response curve is possible. Interestingly, a similar non-monotonic relationship between dopamine dose and neural response has been observed in various brain areas. In these studies, a non-monotonic (inverted-U shaped) function was reported for dopamine levels and neural response in the cortex (Goldman-Rakic, Muly, & Williams, 2000) and striatum (Hu & Wang, 1988; Hu & White, 1997; Nicola, Surmeier, & Malenka, 2000; Nisenbaum, Orr, & Berger, 1988; Shen, Asdourian, & Chiodo, 1992). This Gaussian model analysis was limited to antisaccade errors because differences for the other measurements (e.g. Stroop task), if they existed, were small and Gaussian functions were no better than linear functions.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical non-monotic relationship between baseline antisaccade error and change in antisaccade error post drug treatment. (A) Hypothetical sigmoidal dose-response curves for numerous subjects that differ in their initial baseline performance on the antisaccade task. Each curve represents the hypothetical change in percent error for a subject on the antisaccade task as a function of a drug dose, such as haloperidol. The vertical dotted line represents the actual dose that may be administered to all subjects. It is clearly seen that the change in percent error from no dose (0) to administered dose varies across subjects (depends on the subject’s initial baseline performance). The change in percent error increases as we move from the bottom curves to the middle curves and then decreases again for the top curves. This illustrates a non-monotonic relationship between baseline performance and change in performance as a result of drug administration across subjects. To obtain all the sigmoidal curves, we systematically varied two parameters: (1) The baseline response and (2) the dose at which the performance changes (the “corner” of each curve). The assumption here being that the more cognitively intact patients (represented by curves towards the bottom) may be more resilient to the cognitive effects of the drug. (B) Example non-monotonic (Gaussian-like) relationship between baseline response and change in response from baseline obtained from hypothetical dose-response curves and the administered dose illustrated in Panel A.

Comparison of Impaired and Nonimpaired Schizophrenia Subgroups

The analyses in the previous section were non-parametric. We also tested the idea of heterogeneity in schizophrenia patients using parametric methods. We categorized the schizophrenia subjects based on whether their baseline error rate in antisaccade task was below or above the median (i.e. a median split). Schizophrenia subjects whose baseline error rate in antisaccade task was below the median (N=7) were classified as “nonimpaired” and those above the median (N=6) were classified as “impaired”. Based on this division, we repeated the above-mentioned ANOVAs and t-tests with a new between-subject factor of Group (schizophrenia impaired/schizophrenia nonimpaired/control).

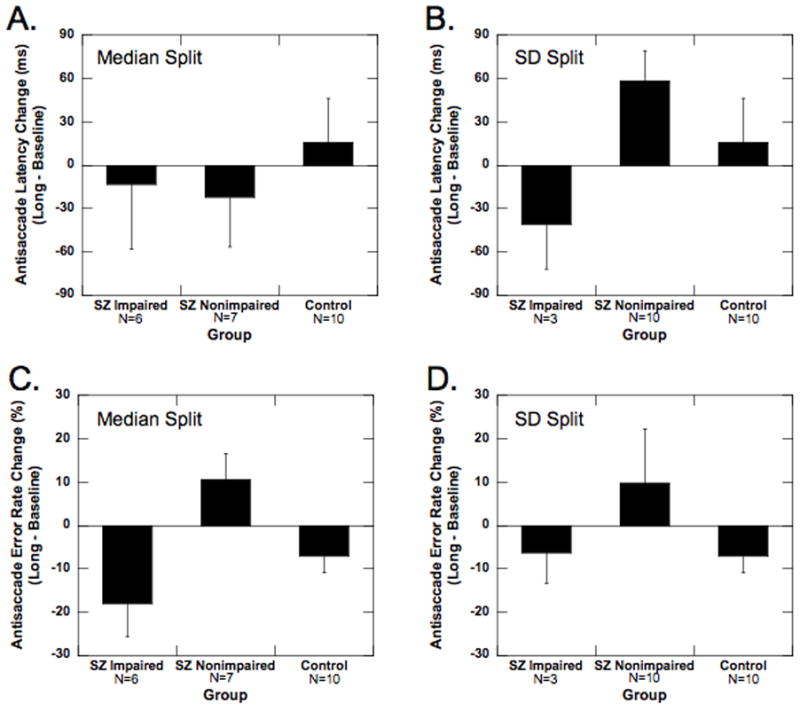

Some previous studies have used a criterion based on normal control performance to categorize schizophrenia subjects. The mean antisaccade error rate (standard deviation) collected for controls was 14.7% (s.d.: 7.7%). Hence, for comparison with other studies, we also classified schizophrenia subjects whose baseline performance was three standard deviations above this mean (i.e., greater than 38% errors) as “impaired” (n=10) and those that did not as “nonimpaired” (n=3). Based on this division, labelled SD split, we repeated the ANOVAs and t-tests that were performed for the median split data. The results of these analyses did not differ qualitatively from the median split analyses. However, given the small size of the nonimpaired group (n=3) in the SD split analyses, we only include the results of these analyses in Figures 4B and 4D and Table 4 for those readers interested in comparing our findings to other studies that have used similar criteria for impaired and non-impaired performance. For all these subgroup ANOVA analyses, we only report significant (p < 0.05) main and interaction effects involving Group.

Figure 4.

Effect of haloperidol treatment on antisaccade performance in impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenia subgroups versus an unmedicated control group. (A, B) Average latency in the antisaccade task for impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenic subgroups and control group when the schizophrenia subgroups are defined by the median split (A) and the standard deviation based split (B). (C, D) Average error rate in the antisaccade task for impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenic subgroups and control group when the schizophrenia subgroups are defined by the median split (C) and the standard deviation based split (D). Data shown are from baseline (white bar), short (gray bar) and long (black bar) sessions. Error bars represent 1 SEM.

Table 4.

Eye Movement Parameters and Clinical Subscale Scores (SE).

| SZ (n=13) | Imp (n=6) | NonImp (n=7) | Imp (n=10) | NonImp (n=3) | Control (n=10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Split | SD Split | |||||

|

Latency (ms)

| ||||||

| Prosaccade | ||||||

| Day 0 | 229.6 (12.2) | 230.3(16.5) | 229.0(15.2) | 228.6(15.9) | 233.2(9.5) | 231.3(10.1) |

| Day s | 214.6(13.5) | 211.6(16.6) | 217.1(15.4) | 215.7(13.7) | 210.8(43.4) | 227.9(7.5) |

| Day l | 226.0(15.9) | 206.5(18.2) | 242.8(16.9) | 213.1(18.6) | 269.2(10.8) | 234.9(7.4) |

|

| ||||||

| Antisaccade | ||||||

| Day 0 | 364.7(26.8) | 323.3(34.8) | 400.3(32.3) | 369.3(34.9) | 349.6(17.6) | 341.0(24.1) |

| Day s | 364.5(29.9) | 379.9(36.1) | 351.3(33.4) | 383.5(30.9) | 301.3(80.2) | 340.0(14.5) |

| Day l | 346.4(31.7) | 309.7(39.0) | 377.8(36.1) | 327.9(39.6) | 408.0(11.9) | 356.9(21.3) |

|

| ||||||

|

Error Rate (%)

| ||||||

| Prosaccade | ||||||

| Day 0 | 2.9(1.1) | 4.5(1.3) | 1.5(1.2) | 3.3(1.5) | 1.5(1.5) | 0.9(0.4) |

| Day s | 2.6(0.7) | 3.7(0.8) | 1.7(0.8) | 2.7(0.8) | 2.3(2.3) | 0.7(0.5) |

| Day l | 2.2(0.9) | 3.2(1.0) | 1.3(0.9) | 2.4(1.1) | 1.6(1.6) | 1.1(0.4) |

|

| ||||||

| Antisaccade | ||||||

| Day 0 | 51.9(7.2) | 72.1(5.8) | 34.5(5.4) | 62.4(5.7) | 16.7(6.2) | 14.7(2.5) |

| Day s | 51.4(7.7) | 59.9(8.7) | 44.1(8.0) | 60.1(7.3) | 22.4(14.0) | 12.8(2.4) |

| Day l | 49.2(7.3) | 54.1(8.5) | 45.0(7.9) | 56.1(6.9) | 26.4(17.9) | 7.5(2.7) |

|

| ||||||

|

Stroop Test

| ||||||

| Word | ||||||

| Day 0 | 70.9(5.3) | 66.0(7.4) | 75.1(6.9) | 69.0(6.7) | 77.3(4.4) | 83.9(5.3) |

| Day s | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Day l | 68.8(5.4) | 67.5(7.4) | 69.9(6.9) | 66.8(6.7) | 75.3(8.7) | 88.6(4.7) |

|

| ||||||

| Color | ||||||

| Day 0 | 48.2(4.4) | 39.2(5.2) | 55.9(4.9) | 45.6(5.3) | 56.7(5.4) | 60.6(3.7) |

| Day s | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Day l | 44.2(3.0) | 42.7(4.6) | 45.6(4.3) | 44.1(3.4) | 44.7(8.3) | 67.4(3.5) |

|

| ||||||

| Word-Color | ||||||

| Day 0 | 27.9(3.3) | 21.7(3.7) | 33.3(3.4) | 24.8(3.0) | 38.3(8.6) | 35.3(2.0) |

| Day s | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Day l | 25.8(1.7) | 24.7(3.4) | 26.7(3.2) | 25.6(2.1) | 26.3(2.6) | 39.6(3.3) |

|

| ||||||

|

PANSS

| ||||||

| Positive | ||||||

| Day 0 | 25.0(1.1) | 25.5(1.7) | 24.6(1.6) | 25.3(0.8) | 24.0(4.6) | -- |

| Day s | 20.4(1.9) | 18.2(2.7) | 22.3(2.5) | 20.0(1.0) | 21.7(8.7) | -- |

| Day l | 15.9(1.5) | 14.5(2.2) | 17.1(2.0) | 15.8(1.2) | 16.3(5.8) | -- |

|

| ||||||

| Negative | ||||||

| Day 0 | 25.3(1.8) | 27.2(2.7) | 23.7(2.5) | 27.5(1.3) | 18.0(5.2) | -- |

| Day s | 22.9(1.5) | 21.5(2.2) | 24.1(2.1) | 23.4(1.6) | 21.3(4.4) | -- |

| Day l | 17.8(1.6) | 16.12(2.4) | 19.1(2.2) | 19.0(1.8) | 13.7(3.2) | -- |

|

| ||||||

| General | ||||||

| Day 0 | 47.6(2.7) | 51.8(3.7) | 44.0(3.4) | 51.9(1.7) | 33.3(3.2) | -- |

| Day s | 36.6(2.8) | 36.0(4.2) | 37.1(3.9) | 40.4(2.4) | 24.0(3.2) | -- |

| Day l | 32.6(2.1) | 28.5(2.7) | 36.1(2.5) | 32.9(2.4) | 31.7(5.0) | -- |

|

| ||||||

| Total | ||||||

| Day 0 | 98.2(4.0) | 104.5(5.6) | 92.7(5.2) | 105.0(1.9) | 75.3(5.3) | -- |

| Day s | 79.9(4.4) | 75.7(6.6) | 83.6(6.1) | 83.8(4.4) | 67.0(10.4) | -- |

| Day l | 66.3(4.3) | 59.2(6.0) | 72.4(5.5) | 67.7(4.9) | 61.7(10.4) | -- |

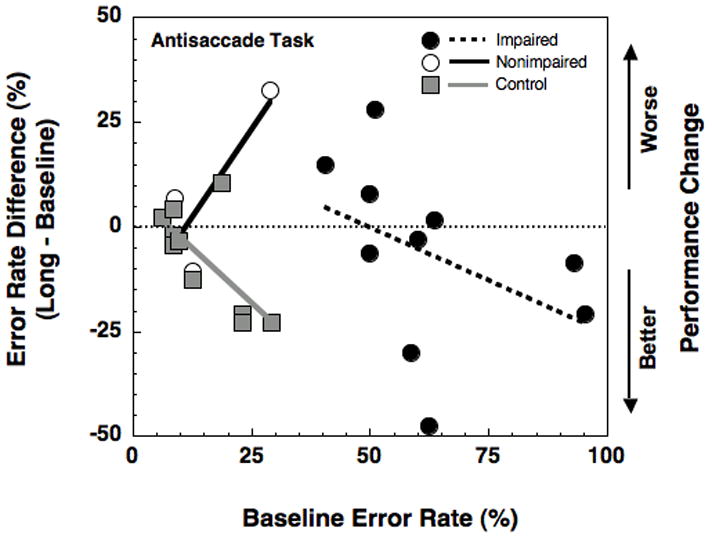

Finally, we also performed a multiple linear regression analysis using a single model and all 13 data points. The multiple regression lines (independent variable: baseline antisaccade error rate; dependent variable: change in antisaccade error rate from baseline to long session) were simultaneously fit to the data from the Control and schizophrenia groups. For the schizophrenia group, we searched for two regression lines (with at least 3 points in each line) that best explained the total variance in all 13 data points. The search for the best two regression lines turned out to yield the two lines shown in Figure 5. This was another way of treating the baseline performance as a continuous variable and independently determining and analyzing the categorical division in the data.

Figure 5.

Change in antisaccade error rate performance (long session relative to baseline session) as a function of baseline antisaccade error rate for impaired (solid black dot, dashed black line) and nonimpaired (open black dot, solid black line) schizophrenic subgroups and control group. The linear regression coefficients for impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenic subgroups and control group are −0.4, 1.7, and −1.05 respectively.

3. RESULTS

Comparison of Schizophrenia and Control Groups

All eye movement, Stroop, and PANSS means and associated standard errors are reported in Table 4 for both the schizophrenia (n=13) and control (n=10) groups.

Latency

All subjects responded faster on the prosaccade task than the antisaccade task (226.9 ms versus 353.1 ms, respectively; three-way ANOVA, Task main effect: F1,21 = 98.61, p < 0.01). Planned t-tests for group differences indicated that there were no differences in prosaccade or antisaccade latency (1) between the two groups, (2) across testing sessions (baseline to long), or (3) between groups across testing sessions.

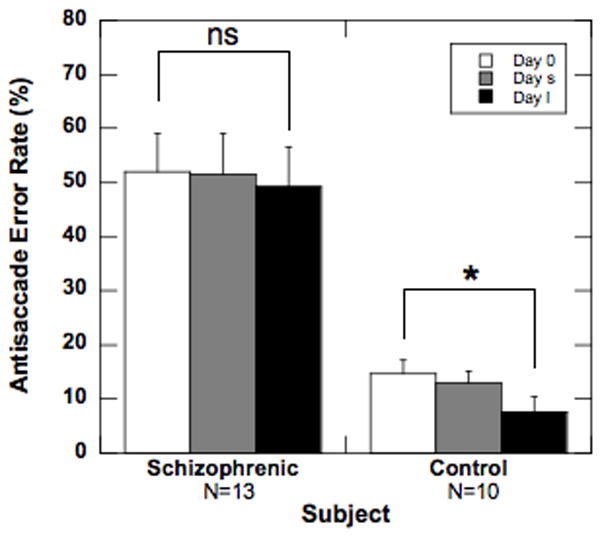

Error Rate

All subjects made more errors on the antisaccade task than the prosaccade task (three-way ANOVA, Task main effect: F1,21 = 62.84, p < 0.01). Schizophrenia subjects made more errors than controls on the antisaccade task but not on the prosaccade task (Task × Group interaction: F1,21 = 25.22, p < 0.01).

Planned t-tests for group differences indicated that there were no differences in prosaccade error rate (1) between the two groups, (2) across testing sessions (baseline to long), or (3) between groups across testing sessions. In contrast, the schizophrenia group as a whole exhibited significantly higher antisaccade error rates than controls (50.8 % versus 11.7 %, respectively; t1,21 = 9.90, p < 0.01; see Figure 2). Across testing sessions, there was no significant change in the mean antisaccade errors within the schizophrenia group. In comparison, in the control group, mean antisaccade errors decreased across testing sessions (long - baseline = −7.2 %, t1,27 = 2.73, p<0.05). Despite these findings, across testing sessions, there were no differences between antisaccade error rate changes in the schizophrenia and control groups (t1,21 < 1, p > 0.10).

Figure 2.

Effect of haloperidol treatment on antisaccade error rate in schizophrenia patients versus unmedicated control subjects. Average error rate in the antisaccade task for schizophrenic and control groups. Data are from baseline (white bar), short (gray bar) and long (black bar) sessions. Error bars represent 1 SEM.

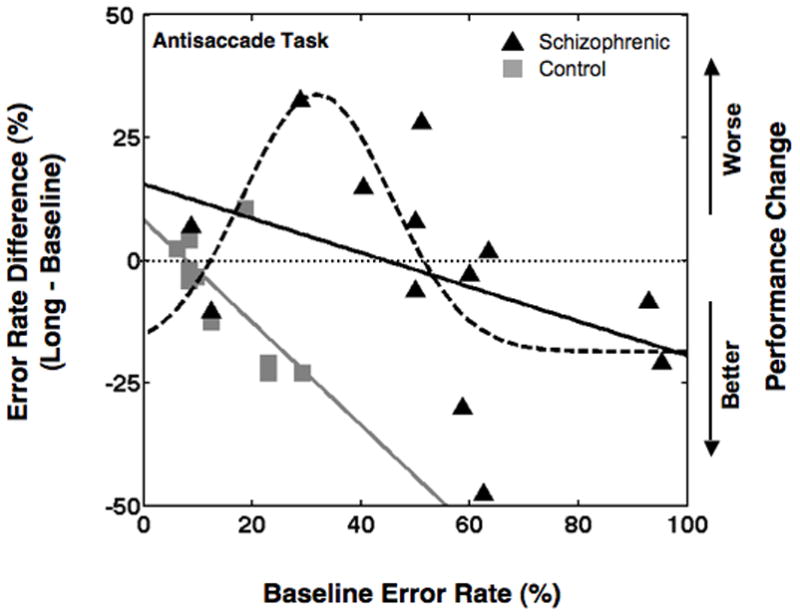

However, when the change in performance is examined as a function of baseline performance using linear models, the schizophrenia and control groups differed significantly (p < 0.05; linear regression analysis; see solid lines in Figure 3). Further, in the schizophrenia group, the change in error rates over time varied non-monotonically as a function of baseline error rate (see Gaussian fit, dashed line, in Figure 3). The Gaussian model was a significant model as indicated by the confidence intervals of the parameters A and σ (A: 32.1 to 73.8; σ: 0.95 to 19.1). In contrast, the linear model for schizophrenia subjects (shown in Figure 3) was non-significant. Further, the Gaussian model accounted for a substantially larger proportion of variance in the data compared to the linear model (Gaussian model: R2 = 0.47, Adj- R2 = 0.29; Linear model: R2 = 0.17, Adj- R2 = 0.09). The Gaussian model also indicates a significant improvement in performance across sessions that is independent of the baseline performance (confidence interval for B: −28.5 to −5.8). Thus, control subjects who had higher error rates at baseline showed a significantly larger improvement over sessions (p < 0.05); in contrast, schizophrenia patients who had lower errors at baseline showed worsening performance across sessions while those who had higher errors changed towards better performance. It should be noted that a Gaussian relationship between change in performance and baseline performance is inconsistent with the phenomenon of regression to mean. The phenomenon of regression to the mean predicts a monotonic relationship between change in performance and baseline performance. These results indicate that, depending on baseline antisaccade performance, a 15 mg dose of haloperidol may have either a beneficial or deleterious effect on the voluntary saccade task.

Figure 3.

Change in antisaccade error rate performance (long session relative to baseline session) as a function of baseline antisaccade error rate for schizophrenic patients (black lines) and control (gray line). The linear regression coefficients for schizophrenic patients and controls are −0.33 and −1.05 respectively. The parameters of the Gaussian fit for schizophrenic patients are A = 52.3, σ = 13.6, β = 31.9 and B = −18.6.

Stroop Task

Schizophrenia subjects had significantly lower Stroop Task scores than controls (47.6 versus 62.6, respectively; three-way ANOVA main effect: F1,21 = 10.12, p < 0.01). The schizophrenia subjects performed worse across testing sessions, whereas the controls improved (−2.7 versus 5.3, respectively; Group × Session interaction: F1,21 = 6.78, p < 0.05). Also, there was a main effect of Subscale (F1.3,30.1 =193.29, p < 0.01), demonstrating that subjects named more items for the WORD subscale than the COLOR or WORD–COLOR subscales (77 versus 53.9 and 31.5, respectively). Planned t-tests showed that schizophrenia subjects performed worse than controls on WORD Subscale (69.8 versus 86.2, respectively; t1,30 = 6.24, p < 0.01), COLOR Subscale (46.2 versus 64, respectively; t1,30 = 6.78, p < 0.01) and WORD-COLOR Subscale (26.9 versus 37.5, respectively); t1,30 = 4.03, p < 0.01). Additionally, in the COLOR and WORD–COLOR Subscales, the two groups had a significant difference in change across testing sessions (t1,30 = 4.10, p < 0.01 and t1,30 = 2.42, p < 0.05 respectively). In the COLOR Subscale, performance of control subjects improved significantly (long – baseline = 6.8; t1,30 = 2.43, p < 0.05), but schizophrenia subjects did not (long – baseline = −3.9). Overall, these Stroop Task data indicate that haloperidol may be impairing cognitive function in schizophrenia or interfering with practice effects that occur in control subjects with repeated exposure to this task.

PANSS

Total PANSS showed gradual improvement across time points (baseline: 98.9; short: 77.9; long: 65.0; F2,24 = 38.63, p < 0.01) and a significant change from the baseline to the long session (long – baseline = −33.9; t1,24 = 5.45, p < 0.01). This finding indicates clinical symptomatology improved with haloperidol administration.

Comparison of Impaired and Nonimpaired Schizophrenia Subgroups

Despite significant clinical improvement during treatment with haloperidol in all schizophrenia subjects, eye movement performance changed in a non-monotonic manner. Depending on baseline antisaccade performance, haloperidol had either a beneficial or deleterious effect on the voluntary saccade task. These findings, which are based on non-parametric analyses of our data, are consistent with previously known heterogeneity within the schizophrenia population on the antisaccade task (Larrison-Faucher, et al., 2004; Sereno & Holzman, 1993, 1995). To obtain parametric statistics of our eye movement data, and to allow comparison of the results of this study with previous studies, we first categorized the schizophrenia subjects into two subgroups: 1. Nonimpaired and 2. Impaired. We then compared the change in error rate (long – baseline) in antisaccade task across groups including control (n=10), nonimpaired, and impaired. We first compared the groups dividing the schizophrenia patients by the median split analysis (impaired=6, nonimpaired=7) and then compared the groups using the SD split (impaired=10, nonimpaired=3). Interestingly, the SD split was consistent with the inflection point of the Gaussian model and the multiple linear regression analysis.

Latency

Median Split

Planned t-tests for group differences indicated that there were no differences in prosaccade and antisaccade latency (1) between the two groups, (2) across testing sessions (baseline to long), or (3) between groups across testing sessions (see Figure 4A). These data suggest haloperidol has no effect on the prosaccade and antisaccade latency of the impaired and non-impaired schizophrenia subjects.

SD Split

There was a significant Session × Group interaction in the three-way ANOVA. (F4,40 = 2.93, p < 0.05). Planned t-tests for group differences indicated that there were no differences in prosaccade latency (1) between the two groups, (2) across testing sessions (baseline to long), or (3) between groups across testing sessions. With respect to antisaccade latency, planned t-tests indicated that the impaired schizophrenia group had a significant decrease in antisaccade latency across testing sessions (long – baseline = −41.4; t1,30 = 2.03. p < 0.05), while the other groups did not change significantly (see Figure 4B). Further, the impaired schizophrenia group had a significantly different change across testing sessions compared to the nonimpaired schizophrenia (t1,30 = 3.14, p < 0.01) and control (t1,30= 2.65, p < 0.01) groups (see Figure 4B). Contrary to the median split data, these data suggest haloperidol may be selectively decreasing antisaccade latency of the impaired schizophrenia subjects.

Error Rate

Median Split

There were significant Group, Task × Group, Session × Group, and Task × Group × Session interactions in the three-way ANOVA (Group: F2,16 = 16.1, p < 0.01; Task × Group: F2,20 = 16.46, p < 0.01; Session × Group: F4,40 = 4.77, p < 0.01; Task × Session × Group: F4,40 = 3.82, p < 0.05). There were no differences in planned paired t-tests of prosaccade error rates. In contrast, for antisaccade error rates, planned paired t-tests showed that the impaired schizophrenia patients had significantly higher error rates than nonimpaired schizophrenia patients (mean difference = 20.9 %, t1,30 = 4.8, p < 0.01). Further, the impaired and non-impaired schizophrenia subjects had significantly higher antisaccade error rates than the control group (impaired vs. control: mean difference = 50.4 %, t1,30 = 12.4, p < 0.01; non-impaired vs. control: mean difference = 29.5 %, t1,30 = 7.6, p < 0.01).

Across testing sessions (baseline to long), error rate in the antisaccade task decreased in the impaired schizophrenia subjects (mean decrease = 18.1 %, t1,30 = 3.96, p < 0.01; see Figure 4C) and controls (mean decrease = 7.2 %, t1,30 = 0.54, p = 0.05; see Figure 4C) but increased in the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects (mean increase = 10.5 %, t1,30 = 2.49, p < 0.05; see Figure 4C).

SD Split

Impaired schizophrenia subjects made more errors on the antisaccade task than nonimpaired schizophrenia and control subjects while showing no differences in prosaccade error rates (Task × Group interaction in a three-way ANOVA: F2,20 = 31.57, p < 0.01). There were no differences in planned paired t-tests of prosaccade error rates. In contrast, for antisaccade error rates, planned paired t-tests showed that the impaired schizophrenia subjects had significantly higher antisaccade error rates than the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects (59.5 % versus 21.8 %, respectively; t1,42 = 6.09, p < 0.01) and the control group (59.5 % versus 11.7 %; t1,42 = 11.4, p < 0.01). The nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects did not differ, statistically, from the controls.

Across testing sessions (baseline to long), error rate in the antisaccade task decreased in the impaired schizophrenia subjects (−6.4 %; t1,27 = 2.60, p < 0.05; see Figure 4D) and controls (−7.2 %; t1,27 = 2.73, p < 0.05; see Figure 4D) but not in the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects (9.7 %; p = 0.15; see Figure 4D).

Multiple Linear Regression

When performance on the antisaccade task was examined as a function of baseline performance using a multiple linear regression analysis, the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects displayed increasing error rates across testing sessions (long – baseline; worsening with haloperidol; see solid black line in Figure 5). This pattern was significantly different (p < 0.05) from controls’ increasing improvement across sessions (p < 0.05; see gray line in Figure 5) as a function of baseline errors. Compared to the controls, the impaired subjects were not different (compare gray and dotted black lines in Figure 5). Thus, while the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects became worse (more errors) across sessions with worsening baseline performance, the impaired subjects did not. Note that this result is also inconsistent with the phenomenon of regression to mean which predicts an improvement with worsening baseline performance in nonimpaired subjects.

Stroop Task

Median Split

There was a main effect of Group in the three-way ANOVA (F2,20 = 5.91, p < 0.05). There was a Group × Session interaction (F2,20 = 8.6, p < 0.01).

Planned t-tests on the WORD-COLOR subscale showed that impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects had worse scores than controls (impaired vs control: t1,28 = 4.3, p < 0.01; nonimpaired vs control: t1,28 = 2.4, p < 0.05). Across testing sessions (baseline to long), on the WORD-COLOR subscale, nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects displayed a marginally significant decrease in number of colors named (mean decrease = 6.6, t1,27 = 1.91, p < 0.1), which was a significantly different change compared to the impaired schizophrenia subjects (t1,27 = 2.67, p < 0.05) and controls (t1,27 = 3.42, p < 0.01), who both showed small but nonsignificant increases. These data underscore the possible negative effect of haloperidol in the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects.

SD Split

Similar to the median split analysis, there was a main effect of Group and a Group × Session interaction (Group: F2,20 = 5.52, p < 0.05, Group × Session F2,20 = 5.06, p < 0.05). The controls improved across testing sessions (control change: 5.3) while the patient groups performance deteriorated (impaired change: −8.7; nonimpaired change: −1.0).

Planned t-tests on the WORD-COLOR subscale showed that impaired schizophrenia subjects had worse scores than controls (25.2 versus 32.3; t1,28 = 4.44, p < 0.01). Across testing sessions (baseline to long), on the WORD-COLOR subscale, nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects displayed a significant decrease in number of colors named (change: −12.0; t1,28 = 2.38, p < 0.05), which was a significantly different change compared to the impaired schizophrenia subjects (change: 0.8; t1,28 = 3.15, p < 0.01) and controls (change: 4.3; t1,28 = 4.02, p < 0.01), who did not change significantly. Although the specific findings are slightly different than the median split analysis, the overall impact of the findings is consistent: Namely, the SD Split analysis of the Stroop data suggest a possible negative effect of haloperidol in the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects.

In sum, when we look at the effect of testing session on the cognitive portion of the Stroop (Word-Color), it is the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects whose performance declines the greatest, indicating perhaps haloperidol is eliminating any practice benefit and selectively impairing the more cognitively intact schizophrenia subjects.

PANSS

Median Split

Impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects did not differ on Total PANSS scores (mean difference = 3.1, F1,11 = 0.2, p > 0.5). Across testing sessions (baseline to long), both the impaired and the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects showed significant improvement (impaired: mean improvement = 45.3, t1,22 = 8.02, p < 0.01; nonimpaired: mean improvement = 20.3, t1,22 = 3.88, p < 0.01). The improvement in Total PANSS was significantly larger in the impaired compared to nonimpaired subjects (t1,22 = 4.6, p < 0.01). These findings indicate haloperidol results in significant clinical improvement in Total PANSS scores for both impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenia subgroups, with greater improvement in the more cognitively impaired group.

SD Split

Impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects did not differ on Total PANSS scores (83.1 versus 72.2, respectively; F1,11 = 1,79, p > 0.10). Across testing sessions (baseline to long), both the impaired and the nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects showed significant improvement (impaired change: −36.2; t1,22 = 8.07, p < 0.01 and nonimpaired change: −26.3; t1,22 = 3.17, p < 0.01). In contrast to the median split analysis, there was no significant difference in clinical improvement between the impaired and nonimpaired subjects (t1,22 = 2.25, p > 0.10). Nevertheless, both subgroup analyses concurred in the findings that haloperidol results in significant improvement in Total PANSS scores for both the impaired and nonimpaired schizophrenia subgroups.

3. DISCUSSION

Summary of Eye Movement and Clinical Results

The results of the present study indicate that although 15 mg of haloperidol has little effect on voluntary saccadic eye movements in schizophrenia patients as a group, individual response varied depending on the status of voluntary eye movement performance prior to treatment. When change in voluntary eye movement performance due to haloperidol in schizophrenia patients is examined as a function of their performance prior to treatment, there is a strong evidence for functional heterogenity. Patients who are cognitively less impaired prior to treatment (baseline antisaccade error rate less than 32% given by β in Gaussian function) show a worsening in post-treatment performance with worsening pre-treatment performance (upward going half of the Gaussian function in Figure 2). On the other hand, patients who are cognitively more impaired prior to treatment (baseline antisaccade error rate more than 32%) show an improvement of post-treatment performance with worsening pre-treatment performance (downward going half of the Gaussian function in Figure 3). Further, when schizophrenia patients are categorized into cognitively-impaired and -nonimpaired subgroups (by median or SD split), the impaired schizophrenia subjects had improved antisaccade performance (decreased latency) after taking haloperidol for 10–14 days, while nonimpaired schizophrenia subjects had worse performance (increased errors). These findings indicate haloperidol may have a selective, detrimental effect on cognitively intact schizophrenia subjects. Interestingly, the cognitive portion of the Stroop Task reflected the worsening performance of the nonimpaired group on haloperidol, but failed to show the improvement of the impaired schizophrenia group shown in Figure 4. When the voluntary eye movement performance of each subgroup is examined as a function of the pre-treatment performance, clear differences are found between impaired and nonimpaired subgroups (see Figure 5). The clinical results of the Total PANSS showed all schizophrenia subjects (regardless of impaired or nonimpaired status) had a clinically significant (>34%) improvement with haloperidol treatment. After subdivision into impaired and nonimpaired groups, this significant improvement remained, indicating that regardless of severity, haloperidol improves clinical symptomology.

Baseline-dependent Practice Effect

It has been shown previously that normal subjects who had higher antisaccade error rates at baseline showed larger improvement on a re-test (Ettinger, et al., 2003). Although, this finding appears consistent with our finding of greater improvement in the impaired schizophrenia subgroup with increasing baseline antisaccade error rate, it can neither explain the impairments in performance with re-test that we report nor the increasing impairment with increasing baseline error rates in the nonimpaired schizophrenia subgroup. Hence, we feel that the changes with performance that we report are specific to the administration of haloperidol.

Implications for Neuropsychological and Clinical Tests

The Stroop Task is a neuropsychological task that requires a subject to inhibit a reflexive process and willfully generate another response (i.e., not naming the word, but naming the color of the ink in which the word is written). This test seems to parallel the cognitive processes responsible for successful completion of the antisaccade task, where a reflexive response to look towards the target light must be inhibited and a saccade must be willfully generated to an untargeted location opposite the light. However, perhaps due to increased task demand (ability to read), the Stroop Task was not as sensitive to frontal-lobe-dependent cognitive change as measured by voluntary saccadic eye movement performance in the present study. Specifically, the Stroop task did not detect the subtle cognitive improvement in the impaired schizophrenia subjects shown in Figures 4 and 5. These findings support the work of Broerse and colleagues (Broerse, Holthausen, van den Bosch, & den Boer, 2001) who found saccadic eye movements to be a more sensitive measure of frontal function than a battery of standard neuropsychological tests.

Clinical improvement in our study (reduction of PANSS scores) did not parallel cognitive improvement, as measured by the antisaccade task. Improvement on a clinical scale should not be equated to an improvement in cognitive functioning and, hence, the latter should be independently assessed.

The Effect of Antipsychotic Dosage

Previous work suggests higher doses of antipsychotics are related to poorer performance on cognitive tasks. Kawai and colleagues (Kawai, et al., 2006) investigated the differential effects of high doses of typical antipsychotics in a group of schizophrenia patients on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. These subjects were tested on 2,200 mg chlorpromazine equivalent and again on a reduced dose of 1,315 mg chlorpromazine equivalent. The result was a significant improvement in the total number of correct responses and preservative errors made. This result was echoed in another study by Hori and colleagues (Hori, et al., 2006), who used medication dosages of over 1000 mg chlorpromazine equivalent. Of the studies that used voluntary eye movement tasks to investigate the effects of typical antipsychotics in schizophrenia, two of them (Cassady, et al., 1993; Crawford, et al., 1995) had patients on high doses and found no changes in error rate. Two other studies examined the effects of low doses of typical antipsychotic medications (less than 300 mg chlorpromazine equivalent). Harris and colleagues found a positive effect (decrease in antisaccade error rate) with low dose typical medication, while Muller and colleagues (Muller, et al., 1999) found no effect of medication. One reason for the discrepant findings among these studies may be a factor beyond medication dosage. Namely, not all schizophrenia patients show a similar cognitive response to haloperidol. That is, pretreatment cognitive function in schizophrenia subjects may influence the cognitive effects of haloperidol. This idea is supported by the results of our study using 750 mg chlorpromazine equivalent dosage of haloperidol and showing no change in error rates (significant decrease in latency) for the cognitively impaired schizophrenia subjects and a significant increase in error rates (nonsignificant increase in latency) for the cognitively intact subjects. Our work here confirms that schizophrenia subjects are a heterogeneous group with differential treatment effects.

Effect of concomitant medication

Even though all of the schizophrenia subjects received the similar daily doses of haloperidol, all subjects were concomitantly treated with benzatropine to reduce side effects. It is possible that benzatropine and not haloperidol negatively affected cognitive processing. However, this is unlikely as both Velligan and colleagues (Velligan, et al., 2002) and Harris and colleagues (Harris, et al., 2006) found no effect of benzatropine on tasks of executive functioning. Furthermore, we are unaware of any study that has shown that benzatropine could improve cognitive performance in impaired (or intact) subjects.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Symptom reduction in acutely ill schizophrenia patients treated with 15 mg of haloperidol was associated with a detrimental effect (increased error rate) on a voluntary eye movement task in those patients who were initially cognitively intact. This decline in performance was also reflected on the Word-Color subscale scores of the Stroop Task. Such deterioration was not evident in those schizophrenia patients who were initially cognitively-impaired prior to haloperidol administration. This suggests that the prior discrepant findings in the literature about the effect of haloperidol on eye movements may simply be due to heterogeneity in the schizophrenia population. Of significant clinical importance, this study indicated (1) changes in symptom reduction may not parallel changes in cognitive performance, (2) voluntary eye movements may be a sensitive measure of cognitive change and (3) schizophrenia patients may have differential cognitive responses to typical antipsychotics depending on whether their cognition is initially intact or impaired. These concepts are crucial to optimal evaluation and treatment of schizophrenia patients given cognition is the strongest predictor of long-term prognosis.

Research Highlights.

This study indicates

changes in symptom reduction may not parallel changes in cognitive performance,

voluntary eye movements may be a sensitive measure of cognitive change and

schizophrenia patients may have differential cognitive responses to typical antipsychotics depending on whether their cognition is initially intact or impaired. These concepts are crucial to optimal evaluation and treatment of schizophrenia patients given cognition is the strongest predictor of long-term prognosis.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Essel Investigator; National Institutes of Health (R01 MH065492, P30EY010608); National Research Service Award (5 T32 NS41226); and National Science Foundation (0924636).

The authors would like to thank Dr. Deborah Levy and Cameron Jeter for valuable comments on the manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Shilpa Ghandi, Vani Pariyadath, and Al Sillah for their assistance in aspects of either data collection or data analysis. Finally, we would like to thank Dr. Alice Chuang for performing the regression analyses of our data.

Abbreviations

- PANSS

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition

- CRT

Cathode Ray Tube

- ANOVA

Analysis of Variance

- MSE

Mean Squared Error

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bechard-Evans L, Iyer S, Lepage M, Joober R, Malla A. Investigating cognitive deficits and symptomatology across pre-morbid adjustment patterns in first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 40(5):749–759. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broerse A, Holthausen EA, van den Bosch RJ, den Boer JA. Does frontal normality exist in schizophrenia? A saccadic eye movement study. Psychiatry Res. 2001;103(2–3):167–178. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozoski TJ, Brown RM, Rosvold HE, Goldman PS. Cognitive deficit caused by regional depletion of dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rhesus monkey. Science. 1979;205(4409):929–932. doi: 10.1126/science.112679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassady SL, Thaker GK, Tamminga CA. Pharmacologic relationship of antisaccade and dyskinesia in schizophrenic patients. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29(2):235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassens G, Inglis AK, Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Neuroleptics: effects on neuropsychological function in chronic schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16(3):477–499. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudasama Y, Robbins TW. Dopaminergic modulation of visual attention and working memory in the rodent prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(9):1628–1636. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleghorn JM, Kaplan RD, Szechtman B, Szechtman H, Brown GM. Neuroleptic drug effects on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1990;3(3):211–219. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(90)90038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford TJ, Haeger B, Kennard C, Reveley MA, Henderson L. Saccadic abnormalities in psychotic patients. II. The role of neuroleptic treatment. Psychol Med. 1995;25(3):473–483. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichelbaum M, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Evans WE. Pharmacogenomics and individualized drug therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:119–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.082103.104724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger U, Kumari V, Crawford TJ, Davis RE, Sharma T, Corr PJ. Reliability of smooth pursuit, fixation, and saccadic eye movements. Psychophysiology. 2003;40(4):620–628. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima J, Fukushima K, Chiba T, Tanaka S, Yamashita I, Kato M. Disturbances of voluntary control of saccadic eye movements in schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23(7):670–677. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi S, Bruce CJ, Goldman-Rakic PS. Neuronal activity related to saccadic eye movements in the monkey’s dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65(6):1464–1483. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, Bebbington P. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. Bmj. 2000;321(7273):1371–1376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS. Psychopathology and the Brain. New York: Raven; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS, Muly EC, 3rd, Williams GV. D(1) receptors in prefrontal cells and circuits. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;31(2–3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Blanch C, Rodriguez-Sanchez JM, Perez-Iglesias R, Pardo-Garcia G, Martinez-Garcia O, Vazquez-Barquero JL, et al. First-episode schizophrenia patients neuropsychologically within the normal limits: evidence of deterioration in speed of processing. Schizophr Res. 2010;119(1–3):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding DC, Basso MA. The tell-tale tasks: a review of saccadic research in psychiatric patient populations. Brain Cogn. 2008;68(3):371–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding DC, Mohapatra L, Shea HB. Temporal stability of saccadic task performance in schizophrenia and bipolar patients. Psychol Med. 2004;34(5):921–932. doi: 10.1017/s003329170300165x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granon S, Passetti F, Thomas KL, Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Enhanced and impaired attentional performance after infusion of D1 dopaminergic receptor agents into rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20(3):1208–1215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-01208.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(3):321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton D, Buchtel HA, Douglas RM. Frontal lobe lesions in man cause difficulties in suppressing reflexive glances and in generating goal-directed saccades. Exp Brain Res. 1985;58(3):455–472. doi: 10.1007/BF00235863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MS, Reilly JL, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA. Longitudinal studies of antisaccades in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2006;36(4):485–494. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Howanitz E, Parrella M, White L, Davidson M, Mohs RC, et al. Symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills in geriatric patients with lifelong schizophrenia: a comparison across treatment sites. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(8):1080–1086. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Rabinowitz J, Eerdekens M, Davidson M. Treatment of cognitive impairment in early psychosis: a comparison of risperidone and haloperidol in a large long-term trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1888–1895. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Ulrich RF. The limitations of antipsychotic medication on schizophrenia relapse and adjustment and the contributions of psychosocial treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32(3–4):243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzman PS, Proctor LR, Hughes DW. Eye-tracking patterns in schizophrenia. Science. 1973;181(95):179–181. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4095.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzman PS, Proctor LR, Levy DL, Yasillo NJ, Meltzer HY, Hurt SW. Eye-tracking dysfunctions in schizophrenic patients and their relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;31(2):143–151. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760140005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori H, Noguchi H, Hashimoto R, Nakabayashi T, Omori M, Takahashi S, et al. Antipsychotic medication and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1–3):138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XT, Wang RY. Comparison of effects of D-1 and D-2 dopamine receptor agonists on neurons in the rat caudate putamen: an electrophysiological study. J Neurosci. 1988;8(11):4340–4348. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04340.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XT, White FJ. Dopamine enhances glutamate-induced excitation of rat striatal neurons by cooperative activation of D1 and D2 class receptors. Neurosci Lett. 1997;224(1):61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton SB, Crawford TJ, Puri BK, Duncan LJ, Chapman M, Kennard C, et al. Smooth pursuit and saccadic abnormalities in first-episode schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):685–692. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton SB, Ettinger U. The antisaccade task as a research tool in psychopathology: a critical review. Psychophysiology. 2006;43(3):302–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai N, Yamakawa Y, Baba A, Nemoto K, Tachikawa H, Hori T, et al. High-dose of multiple antipsychotics and cognitive function in schizophrenia: the effect of dose-reduction. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(6):1009–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Young CA, Rock SL, Purdon SE, Gold JM, Breier A. One-year double-blind study of the neurocognitive efficacy of olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;81(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern RS, Glynn SM, Horan WP, Marder SR. Psychosocial treatments to promote functional recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):347–361. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrison-Faucher AL, Matorin AA, Sereno AB. Nicotine reduces antisaccade errors in task impaired schizophrenic subjects. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28(3):505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh RJ, Kennard C. Using saccades as a research tool in the clinical neurosciences. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 3):460–477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DL, Holzman PS, Matthysse S, Mendell NR. Eye tracking and schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20(1):47–62. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidow MS, Elsworth JD, Goldman-Rakic PS. Down-regulation of the D1 and D5 dopamine receptors in the primate prefrontal cortex by chronic treatment with antipsychotic drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281(1):597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidow MS, Goldman-Rakic PS. A common action of clozapine, haloperidol, and remoxipride on D1- and D2-dopaminergic receptors in the primate cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(10):4353–4356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig C, Meck WH. Chronic treatment with haloperidol induces deficits in working memory and feedback effects of interval timing. Brain Cogn. 2005;58(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, McGurk SR. The effects of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(2):233–255. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishara AL, Goldberg TE. A meta-analysis and critical review of the effects of conventional neuroleptic treatment on cognition in schizophrenia: opening a closed book. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(10):1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer AM. Cognitive function in schizophrenia--do neuroleptics make a difference? Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;56(4):789–795. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller N, Riedel M, Eggert T, Straube A. Internally and externally guided voluntary saccades in unmedicated and medicated schizophrenic patients. Part II. Saccadic latency, gain, and fixation suppression errors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;249(1):7–14. doi: 10.1007/s004060050059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz DP, Everling S. Look away: the anti-saccade task and the voluntary control of eye movement. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(3):218–228. doi: 10.1038/nrn1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah HA, Targum SD, Tandon R, McCombs JS, Ross R. Defining and measuring clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(3):273–282. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola SM, Surmeier J, Malenka RC. Dopaminergic modulation of neuronal excitability in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:185–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenbaum ES, Orr WB, Berger TW. Evidence for two functionally distinct subpopulations of neurons within the rat striatum. J Neurosci. 1988;8(11):4138–4150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04138.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrot-Deseilligny C, Muri RM, Nyffeler T, Milea D. The role of the human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in ocular motor behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1039:239–251. doi: 10.1196/annals.1325.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigache RM. The clinical relevance of an auditory attention task (PAT) in a longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia, with placebo substitution for chlorpromazine. Schizophr Res. 1993;10(1):39–50. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(93)90075-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploner CJ, Gaymard BM, Rivaud-Pechoux S, Pierrot-Deseilligny C. The prefrontal substrate of reflexive saccade inhibition in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(10):1159–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdon SE, Malla A, Labelle A, Lit W. Neuropsychological change in patients with schizophrenia after treatment with quetiapine or haloperidol. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26(2):137–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radant AD, Dobie DJ, Calkins ME, Olincy A, Braff DL, Cadenhead KS, et al. Successful multi-site measurement of antisaccade performance deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;89(1–3):320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly JL, Lencer R, Bishop JR, Keedy S, Sweeney JA. Pharmacological treatment effects on eye movement control. Brain Cogn. 2008;68(3):415–435. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remillard S, Pourcher E, Cohen H. The effect of neuroleptic treatments on executive function and symptomatology in schizophrenia: a 1-year follow up study. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi P, Zald D, Li R, Park S, Ansari MS, Dawant B, et al. Sex differences in amphetamine-induced displacement of [(18)F]fallypride in striatal and extrastriatal regions: a PET study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1639–1641. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, Geisler S, Koreen A, Sheitman B, et al. Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(4):544–549. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]