Abstract

Few studies have examined the migration and acculturation experiences of Latino youth in a newly emerging Latino community, communities that historically have had low numbers of Latino residents. This study uses in-depth interview data from the Latino Adolescent, Migration, Health, and Adaptation (LAMHA) project, a mixed-methods study, to document the experiences of Latino youth (ages 14–18) growing up in one emerging Latino community in the South – North Carolina. Using adolescent’s own words and descriptions, we show how migration can turn an adolescent’s world upside down, and we discover the adaptive strategies that Latino immigrant youth use to turn their world right-side up as they adapt to life in the U.S.

Keywords: Latino adolescent immigrant, migration, acculturation

As a result of both migration and births to immigrant women, Latino youth (ages 10–19) are one of the fastest growing youth segments of the United States population (U.S. Census, 2008). In 2000, nearly 1 out of 5 Latino children (ages 0–18) was foreign-born (IPUMS, 2000). For most of these immigrant children, the decision to move to the United States (U.S.) was not their own. With hopes and dreams of a better life for their children and themselves, their parents decided to immigrate (Perreira, Chapman, & Livas-Stein, 2006; Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco, 2001). There are, however, costs involved in migration (Massey et al., 2002), and the migration process includes a myriad of stressors such as loss of support from an extended family, displacement from homes, loss of social status, discrimination, and economic hardships (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001; Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco, 2001; Zuniga, 2002).

Immigration can be particularly difficult for the children of immigrants. In one study examining more than 400 immigrant families, children reported more immigration-related stressors than their parents. This high level of stress significantly compromised children’s psychosocial well-being (e.g., causing depression and anxiety) and school adjustment during the first year after migration (Levitt et al., 2005). At the same time, children of immigrants can be remarkably resilient. Despite high levels of socio-economic risk factors, immigrant youth tend to have better health behaviors, better health outcomes, and higher academic achievement than their native-born peers (see Fuligni & Perreira 2009 for a review).

Though many studies on immigrant assimilation have compared and contrasted the health and education outcomes of first-generation (i.e., foreign-born youth with foreign-born parents), second-generation (i.e., U.S.-born youth with foreign-born parents), and third-plus generation youth (i.e., U.S.-born youth with U.S.-born parents), few have qualitatively examined the migration and acculturation experiences of first-generation youth (Gibson, 1988; Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco, 2001; Zhou & Bankston, 1998). Even fewer have examined the migration and acculturation experiences of Latino youth, especially those growing up in newly emerging Latino communities, communities with historically low numbers of Latino residents (Williams, Alvarez, & Hauck, 2002). Because newly emerging Latino communities typically lack the social networks and institutions that facilitate immigrant adaptation to the U.S. and support economic development among Latinos, the experiences of Latino youth settling in them may differ greatly from their peers in more established Latino communities (e.g., Los Angeles).

This study uses in-depth interview data from the Latino Adolescent, Migration, Health, and Adaptation (LAMHA) project to document the experiences of Latino youth (ages 14–18) growing up in an emerging Latino state in the Southeastern region of the US – North Carolina. Fed primarily by immigration from Mexico, North Carolina had the fastest growing Latino population in the country between 1990 and 2000 (Suro & Tafoya, 2004). The migration of Latinos to North Carolina represents an emerging trend throughout the Southeast and provides an ideal setting for gaining insight into the experiences of Latino youth in the South. As eloquently expressed by one of our study participants, we show how migration can turn an adolescent’s world ‘upside down,’ and we discover the adaptive strategies that Latino immigrant youth use to turn the world right-side up as they acculturate to life in the U.S. Specifically, we consider how first-generation Latino adolescents characterize their migration and acculturation experiences; how migration affects their normative development; and how they adapt to the challenges of international migration and settlement in a new country.

THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Three theoretical frameworks inform our analysis – cultural-ecological theories of child development, acculturation theory and Sluzki’s stages of migration framework, and risk-resilience and competence perspectives on positive developmental outcomes. Cultural-ecological theories provide a framework for understanding the development of children from ethnic minorities and immigrant families (Garcia Coll et al., 1996). These theories argue that the cultures, lifestyles, and developmental outcomes of ethnic minority children reflect adaptive responses to contextual demands in their families, schools, and neighborhoods (Garcia Coll et al., 1996). They reject deficit models which presume that normative development for children in white middle-class families should be the basis for development in non-white ethnic minority families as well. Instead, normative development is understood to vary between cultural groups (Greenfield, 1992). From this perspective, migration can be understood as a process which creates unique contextual demands and reshapes normative development.

Defined as the process of cultural exchange that occurs between groups when they come into continuous contact, acculturation and the experiences that comprise acculturation shape the daily lives of immigrant youth (Gonzales, Fabrett, & Knight, 2009). Some researchers and policy makers implicitly characterize acculturation as a unidirectional process through which immigrant youth adopt the beliefs and behaviors of the dominant culture. In contrast, our research acknowledges that these youth are not only shaped by their new communities, but also that their presence and actions re-shape their communities. Moreover, they can selectively acculturate to their new homes by picking and choosing the cultural beliefs and behaviors that will promote their well-being and by actively engaging with individuals in their communities to create the resources they need (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001).

The use of selective acculturation strategies can help immigrant youth mitigate the stress of moving and adapting to a new environment (i.e. migration and acculturative stress). A modified version of Sluzki’s five stages of migration framework provides a template for understanding sources of stress throughout the migration process and adolescents’ responses to these stressors (Zuniga, 2002). In the first stage, the preparatory stage, youth’s parents make a decision to leave. They may or may not discuss the decision with their child, migrate together with their child, or provide their child with an opportunity to say good-bye to them or other family members and friends. In the second stage, the act of migration, youth travel to their new homes either with their parents or to rejoin their parents. In this stage, their mode of travel (e.g., walking vs. flying), their accompaniment during travel (e.g., traveling with a smuggler vs. a trusted family member), and the hardships experienced during travel (e.g., determent, assault, or hunger) influence the level of stress they experience during migration and subsequently, their capacities to adapt to their new homes. Sluzki hypothesizes that the third stage of migration, initial contact, is often characterized by a honeymoon period during which youth begin the tasks of reconnecting with family members, enrolling in schools, learning a new language, and experiencing a new culture. With so many new stimuli and activities to accomplish, youth and their parents have little time to dwell on the changes they are experiencing or to mourn the loss of friends, family, and home. It is only in the fourth stage or the settlement stage that the psychological stresses of acculturation take hold and youth and their parents may begin to realize changes in their economic situation, family dynamics, and social roles. Finally, in the fifth stage of migration, the transgenerational stage, long-term cultural shifts occur within the family, a new second generation is born, and families begin the process of negotiating cultural differences between the foreign-born generation and the new generation born and raised in the new country. In our analysis, we identify three phases of migration – the pre-migration, migration, and post-migration. The latter combines Sluzki’s initial contact, settlement, and transgenerational stages.

The risk-resilience perspective guides our analysis at each stage of migration and helps us understand how immigrant youth succeed when their development is threatened by the challenges of migration (Schoon, 2006). Using adolescents’ own words and perspectives, we highlight the risks that emerge during the immigration process and the adaptive strategies that immigrant children employ to respond to these risks and to adjust to life in the U.S. We begin with their experiences in their home countries (pre-migration), move to discussing their migration journeys (migration), and conclude with consideration of their acculturation experiences (post-migration). In our analysis, we identified vulnerabilities that increased the risk of negative developmental outcomes and resiliencies that reduced these risks. In addition, we show how risks and resilience can also work together to promote normal development and positive outcomes (i.e. competencies; Yoshikawa & Seidman, 2000). Based on our discussions with Latino immigrant adolescents, we then built a model of risk-resiliency factors that influence adolescent development at each stage of the migration process.

METHODS

Data

We use data from the Latino Adolescent Migration, Health, and Adaptation Project (LAMHA), the first population-based study of mental health, migration and acculturation among first-generation Latino youth living in a new receiving state, North Carolina. The LAMHA study used a mixed-methods approach that combined qualitative interviewing with survey-based data collection. Using a stratified-cluster sample design, 283 first-generation Latino immigrant youth ages 12–19 were recruited from 11 high schools and 14 middle schools to participate in the study.1 These 283 adolescents as well as 283 of their primary caregivers completed a 2-hour long interviewer-administered survey containing detailed questions on mental health, family life, migration experiences, and acculturation experiences. Of those youth who participated, 20 youth ages 14 to 18 (at least 1 boy and 1 girl from each of the 9 participating school districts) were randomly selected to participate in an in-depth, qualitative interview. Survey data were collected between August 2004 and February 2006. Qualitative interview data were collected between November 2005 and March 2006. Additional details on the study and sampling design are published in Perreira et al. (2008). This paper primarily uses data from the in-depth interviews conducted with adolescents.

Participants

Reflecting national trends, adolescents who participated in the LAMHA study were from a variety of Latin American countries. In the full LAMHA sample (N=283), 73% of the students were from Mexico, 22% from other Central American countries of the Caribbean, and 4% from South America. The vast majority (95%) were not U.S. citizens and nearly two-thirds (65%) had lived in the U.S. for 5 years or fewer. The average age of the adolescents was 14. Most (66%) had moved to the U.S. between the ages of 6 and 12. Fifty-five percent of the youth lived with two biological parents. Their primary caregivers were 39 years old on average, mostly mothers (76%) who spoke only Spanish (63%), and had lived in the U.S. for over 5 years (63%). Moreover, adolescents’ caregivers had eight or fewer years of education (53%), worked full or part-time (79%), and had an average monthly income of $1,869 which supported five household members. As a result, most of the adolescents we interviewed were living in poverty, $23,400 for a family of 5 in 2006 (U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 2006).

The characteristics of adolescents participating in the qualitative interviews reflected the characteristics of youth participating in the broader study (Table 1). Although several had lived in communities such as California, New York, New Jersey, Texas, or Florida prior to moving to North Carolina, the majority had moved with their parents to the United States from Mexico within the past 5 years. Their parents primarily spoke Spanish, worked in the service sector, and did not have a high school degree. There are exceptions to every rule, however, and a few of the Latino youth we interviewed were from countries other than Mexico, had college-educated parents, and were living middle-class lives in the U.S. Their stories help us to provide a more complete picture of the lives of Latino immigrant youth growing up in the emerging South and a more nuanced interpretation of their migration and acculturation experiences.

Table 1.

Brief Description of LAMHA Qualitative Study Participants

| Pseudonym | Urban County | Gender | Age | Country of Origin | Primary Language of Interview | Years in U.S. | Separated from Parent | Parents' Education | Two-parent Family |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alex | No | Male | 17 | Mexico | English | over 5 | No | HS Graduate | Yes |

| Alonso | No | Male | 18 | Mexico | English | over 5 | No | Less than HS | No |

| Ana | Yes | Female | 16 | Mexico | Spanish | under 5 | Yes | Less than HS | Yes |

| Carlos | Yes | Male | 15 | Other Cen. Am. | Spanish | under 5 | Yes | Unknown | No |

| Chuchi | Yes | Male | 16 | Mexico | English | over 5 | Yes | Less than HS | Yes |

| David | Yes | Male | 14 | Mexico | English | over 5 | Yes | Less than HS | No |

| Droopi | Yes | Male | 15 | Other Cen. Am. | English | over 5 | Yes | Less than HS | No |

| Erica | Yes | Female | 15 | Mexico | Spanish | under 5 | No | Less than HS | Yes |

| Fernandina | Yes | Female | 14 | Other Cen. Am. | English | under 5 | Yes | HS Graduate | No |

| Isabel | No | Female | 14 | Mexico | Spanish | equals 5 | No | HS Graduate | Yes |

| Jesus | Yes | Male | 14 | Mexico | English | under 5 | No | Less than HS | No |

| Joey | No | Male | 14 | Mexico | Spanish | equals 5 | Yes | Less than HS | Yes |

| Laura | Yes | Female | 14 | Mexico | English | equals 5 | No | HS Graduate | Yes |

| Laura | Yes | Female | 16 | Mexico | Spanish | under 5 | Yes | Less than HS | Yes |

| Licho | No | Male | 15 | Mexico | Spanish | equals 5 | No | Less than HS | Yes |

| Luis | No | Male | 17 | Mexico | Spanish | over 5 | No | HS Graduate | Yes |

| Maria | No | Female | 16 | Mexico | Spanish | equals 5 | No | Less than HS | Yes |

| Nancy | Yes | Female | 16 | Mexico | English | under 5 | No | HS Graduate | Yes |

| Opi | Yes | Male | 17 | Mexico | English | over 5 | Yes | College Grad. | Yes |

| Wendy | Yes | Female | 14 | Other Cen. Am. | English | under 5 | Yes | HS Graduate | Yes |

Note: Parents’ education is the highest education level reported by the mother or father. Separation from parents is recorded when the parent and child lived in different countries for at least one year before the child joined the parent in the U.S. Data are grouped to avoid the possibility of deductive disclosure. Adolescents chose their own pseudonyms

Procedures

Two bilingual research associates interviewed adolescents in their homes. Interviews lasted approximately 1.5 to 2 hours and were conducted in the adolescent’s preferred language, either Spanish or English. Several adolescents moved between languages during their interviews depending on whether they felt more comfortable expressing their viewpoints on a particular topic in either English or Spanish. After the completion of each interview, interviewers simultaneously transcribed and translated the Spanish interviews into English. The translations and transcriptions were subsequently reviewed and verified by the Principal Investigator and discussed in weekly team meetings with the interviewers/transcribers.

Data Analysis

As recommended by Miles and Huberman (1994), the analytic process began during the data collection phase of the study and proceeded in three stages. In the first stage, interviewers met weekly with the principal investigator to discuss the interviews, develop notes on key themes, and write vignettes to summarize the survey data for each adolescent interviewed and to link it to the qualitative data, a procedure similar to the technique used by Saldaña (2003) used to link longitudinal qualitative interviews. These meetings provided the principal investigator an opportunity to provide feedback to interviewers, identify themes brought up by adolescents where additional probing was needed, and work with the interviewers to check for rival explanations and identify atypical cases as the interviewing proceeded.

After the completion of data collection, transcripts were uploaded into ATLAS.ti Version 5.0 (Muhr, 1997) for additional analysis. In the second stage of the analysis, the authors independently read each transcript in order to identify main ideas and meanings. They generated tentative labels to capture the essence of each idea and compared and contrasted their notes. In the third stage, we reviewed the data and clustered similar ideas together into themes and codes representative of each theme (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Based on the coding scheme developed, the first author then coded transcripts using ATLAS.ti. The constant comparison method was used to identify other emerging themes, with all transcripts being re-read to ensure consistent coding of the emerging theme. Upon the completion of coding, the first and second author created domain charts that mapped concepts and the interrelationships between concepts. These charts helped us to evaluate atypical cases that did not fit the pattern identified for the majority. All quotes presented in the results are illustrative of the many provided by participants. In places, we also integrate descriptive data from our survey with the qualitative data. These descriptive data also help provide a sense of how typical a particular youth’s experience is.

RESULTS

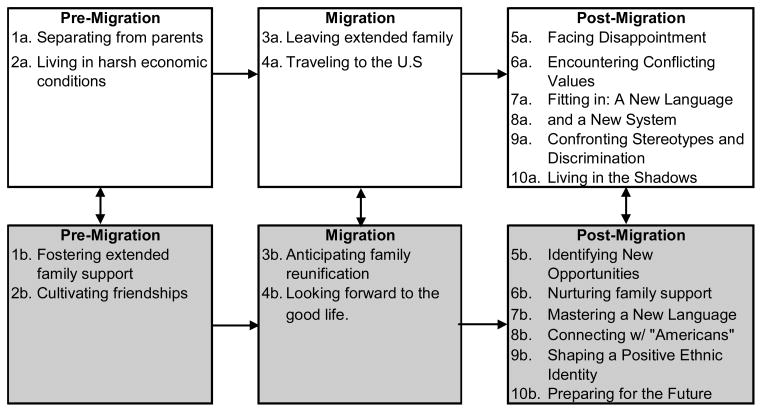

Throughout our analysis, we identified three phases of the migration journey -- pre-migration, migration, and post-migration. Within each phase, we uncovered risk factors that affect the Latino adolescents’ lives and strategies that make them resilient and enable them to succeed despite the risks they face. Figure 1 provides a pictorial overview of our results. The unidirectional arrows indicate how risk and resilience in one phase of migration shape risk and resilience in the subsequent phase of the migration journey. For example, poverty and the harsh economic conditions that youth experience prior to migration predispose their families to migration and affect the mode of travel used to migrate to the U.S. (e.g., walking and crossing the border as an undocumented immigrant). The bidirectional arrows indicate how risks and resilience influence each other throughout each phase of the migration journey. For instance, separation from their parents can lead youth to strengthen their ties to extended families members which can subsequently lessen the stresses associated with separation from parents.

Figure 1. Risk and Resilience through the migration and adaptation process.

Note: White boxes denote sources of risk. Gray boxes denote sources of resilience

The Pre-migration Experience

Facing Economic Hardship and Family Separation

For Latino youth, the immigration process begins in their home countries where economic hardship and family separation first turn their worlds’ upside down. Although a few adolescents reported enjoying an upper-class lifestyle in their home countries and a few others indicated that they had lived in poverty, most considered themselves from middle-class families in their home countries. As evidence of their middle-class status, they informed us that they had indoor plumbing and electricity. Although, as described by Maria, they often lived in small towns where they observed substantial poverty and at times they would have to conserve their money.

[In Mexico], there isn’t very much money. And you have a limit on things. Clothing is bought once a year, sometimes there’s nothing more to eat than beans. Many people don’t have anything to eat and people [live] on the streets.

[Maria].

The least well off shared one or two bedrooms with several family members and had homes built of cement blocks, with no indoor plumbing, and dirt floors. For those with financial security like Alex, parents were working in professional fields (e.g., banking, dentistry), and their lifestyles included having television and Video Cassette Recorders (VCR) in their bedrooms, a maid, and attending private schools.

I know we had a nice big house [in Mexico] and down the street was where they make tortillas and you can walk, get your bicycle, go to the little stores that were there.…I don’t know if you can call us rich or not. It was a three story house with a big pool, a big yard, with a wall, and you had to open the big fences to get in our house, for cars or humans….It was nice, but I guess the money was low and stuff like that and that’s why we moved here.

[Alex]

In fact, as Alex recalled later in his interview, his father had lost his job and could not find a new one in Mexico. Whether they remembered just getting by, like Maria, or having substantial resources, like Alex, they moved to improve their living conditions and financial situation. As Chuchi summarizes, “[My parents moved], to give us a better life, maybe, than in Mexico. So they could give us everything we wanted.” Data from the LAMHA survey further highlights this result. Fifty percent of both adolescents and their caregivers indicated that they primarily moved for job-related reasons. The remainder indicated that family reunification, political and safety reasons, educational opportunities, or some combination of these factors motivated them and their families to move to the U.S. When asked why they moved to North Carolina, specifically, youth indicated that their parents had heard that there were fewer Hispanics in the state and, consequently, less competition and more jobs for Hispanics.

Chuchi also said that he was separated for about eight years from his parents before being re-united. This pattern of parents migrating first and later sending for their children is common. Indeed, 38% of the LAMHA caregivers who completed the survey portion of the study indicated that during the migration process they were separated from their child for one month to one year. An additional 32% reported being separated from their child for over a year. Only 30% of caregivers reported migrating together with their children. Although adolescents understood that financial difficulties necessitated their parents’ immigration to the U.S., they typically expressed mixed feelings towards their parents’ migration. On the one hand, their parents’ migration provided them with remittances to improve their standard of living at home. On the other hand, they recalled feeling distressed and anxious when their parents moved away and left them behind in the care of grandparents, extended family, or neighbors. Unable to hold back tears, Alonso shared the memory of his mother leaving and expressed these competing sentiments.

I remember when she left, we were in school, so we came back and [stops talking, begins to cry] it’s sad [chokes up], you go to school one day and come back and your mom’s not there [still crying]. I think that story is very similar to other kids. You know, their parents try to minimize, I don’t know, the cryin’ and all this stuff. So they try to leave whenever their kids are not at home or somethin’. In my case, I mean, it wasn’t that bad, I had my grandparents, my aunts and uncles, but I mean, it’s still bad whenever you come home and you think… [He chokes up and does not complete his thought] I have to say, things did get better when my mom moved over here [to the U.S.]. There was more income. So I couldn’t really say life changed for the worse, I mean it’s something that, I mean, you miss your parents, your mom, but, since you’re living with relatives, that you’ve spent most of your life with, it minimizes that. But …the quality of life did improve greatly.

[Alonso]

At the age of 9, his mother, not knowing how to say good bye, had left Alonso with his grandparents and did not send for him for 2 years. During this long period of separation, he remembered talking to his mother on the telephone only three or four times.

Fostering Family Support and Cultivating New Friendships

When their parents left, most youth responded by strengthening their emotional bonds to large support networks of extended family members, neighbors, and friends. Even when only one of their parents left for the U.S., youth sought out additional social connections in an effort to strengthen the family. As Licho, who was left with an Aunt and then a neighbor, says,

You have to support each other. My sister, well she cried all the time. [We were] without my mom or my dad. We were so alone. We had no family in the town anymore after my aunts left. We knew this woman [the neighbor], but it wasn’t the same as if we were together with our family. I say that you have to support each other like a family, like I supported my sister…My friends were [also] really good. We played soccer and we went fishing. We hunted with our B.B. guns. Really. It was so much fun.

[Licho]

Fernandina’s and Alonso’s experience, however, are more typical of other youth in our study. Large extended family networks help to assuage the pain of separation and keep some continuity in the lives of children of immigrants.

[After my parents left] I lived in my grandma’s house and like there were always a lot of people there. My uncles, my aunts and my cousins. And you know, I never felt alone. I was always around people, and my sister was with me and everything.

[Fernandina]

[After my mom moved to the U.S.], we were with family. We were very close to my grandparents and everything. I mean, you miss your parents, your mom, but since you’re living with relatives, that you’ve spent most of your life with, it minimizes that…I mean, like, for example, for us, it wasn’t really painful [when mom left] because we had been living with my grandparents about two years, and my aunts and uncles, and [my mom] being the oldest, and me being the first kid, and my brothers, there really weren’t a lot of kids to focus on except us, so you are with family.

[Alonso]

The Migration Experience

Leaving Extended Family

For the majority (70%) of first-generation Latino immigrant youth surveyed who had to adjust to the absence of one or more parents, their worlds were again turned upside down when they were asked to join their parents in the U.S. Although most Latino youth are elated to hear that they will be reunited with their parents, for some the move is involuntary. As a result, they may experience some of the additional psychological stress associated with unplanned and involuntary migrations (Ogbu, 1991; Zuniga, 2002). Whether voluntarily or involuntary, all the youth faced the emotional distress of being separated from their loved ones for the second time, this time from their extended family members and friends. Describing the day that her mother told her and her siblings that they would be moving to the U.S. to join with their father, Erica expressed mixed emotions.

My mom gathered us all in the living room and told us, “You know what? Your dad wants us all to go and be together.” We said, “Oh no, why?” We didn’t want to separate from the rest of the family. My mom said, “I understand but we have been apart from your father too many years and I really miss your dad and he misses us and I want to be altogether.”

[Erica]

Traveling to the U.S

Whether they migrated to the U.S. with valid visas or were undocumented, nearly all of the youth in our qualitative interviews reported enduring arduous and stressful travel conditions. Similarly, the vast majority of both caregivers (77%) and adolescents (67%) in the LAMHA survey reported that the experience was somewhat to very stressful. For some, the journey took several months and included multiple stops in unfamiliar places. When both parents were already living in the U.S., youth often made the trip with adults who were strangers entrusted with their safety. Though for some this meant a relatively easy plane flight to the U.S, they still traveled clandestinely, for example as a couple’s children, and had to be vigilant about protecting their assumed identities. Alex described making the journey with his mother, father, and a ‘coyote’ to assist them:

He [the ‘coyote’] took me across the river with my mom and we ran, we had to run and then finally we caught up with my Dad. And my Dad [and Mom] had to go back and get some luggage so they had to leave me in this house for at least an hour and I was crying the whole time because I wanted my mom. I was saying, “Mommy, Mommy, I was just crying, crying, I would not stop crying for that whole hour until my Mom got there. We didn’t have that much food ‘cause my dad didn’t have that much money. And the lady [in the house] gave us some apples and bananas. [My parents] did not eat ‘cause they gave me all the food, I was hungry. It was [a] hard and very hungry trip.

[Alex]

Maria described her fear of migrating with her mother and sisters, and without the protection of a man, “We’re just women. We came just with women and no one else, my mom, my sister, a cousin, and a little boy cousin. You don’t know if they are going to rape you or just steal your money and leave you abandoned in the desert.”

Looking forward to the Good life and Anticipating Family Reunification

While it is difficult for Latino youth to separate from their extended family members and endure the stressful journey to the U.S., many of the adolescents interviewed explained that their anticipation of the ‘good life’ in the U.S. and reunification with parents and siblings helped them overcome these difficulties. Describing his excitement about coming to the U.S., Droopi states:

Only thing I moved here ‘cause I wanted to see my parents ‘cause it had been a long time since I hadn’t seen them and I thought that that was a good chance to come here and see them for the first time, I mean, ‘cause it had been a long time. I had even forgot their faces, I couldn’t even recognize them!…And I wanted to try how it felt, like being on an airplane too. And come over here and see new people, the way they speak, ‘cause my mom when she called up down over there [His home country] she always was like speaking English to us.…So I always was kinda like, always wanted to try to speak another language.…I wanted to see this country. That’s why I came here. I wanted to see how it was, what kind of people where here. ‘cause my mom she was always used to talk good things about this country and that’s why I always wanted to try it and see how it felt being here.

[Droopi]

Isabel, shared Droopi’s excitement, as she comments, “I mean I was excited. I wanted to see my mom. And I mean, I heard a lot of things about the United States. Like, you have so many things here and all that. So I mean, it was exciting, I was excited to come.”

The Post-migration Experience

Facing Disappointment and Identifying New Opportunities

Though Latino youth approach the migration journey with a combination of trepidation and excitement, they once again experience their worlds turning upside down when they face the realities of settlement in the U.S. Alex, provided us with the metaphor of ‘turning the world upside down’ as he discussed the myriad of changes he experienced upon moving to the U.S.

It was like the world just turned upside down for me. I was like why did we move? I got to learn this other language and it was killin' me. I had to go to school and I heard everybody around me talking and I was like “what are they sayin'?” It was a complete change from where I used to live. And everything just turned upside down -- the language, the way I had to do things. I had to sleep with my parents. I had to share rooms with other people I didn’t know. It was strange, hard. My mom used to work as a secretary [back home]. She used to wear little skirts, high heels and make up. And it was real hard. ‘cause coming from an office where you sit down and do paperwork, use calculator, got your little pencils, and to come here and work with turkeys and wake up early in the morning, the sun wasn’t even up! It was strange, hard.

[Alex]

Isabel shared this sentiment.

I thought I was going to a place equal to where I was from [referring to home country], a good place. When I got here I realized this wasn’t like my old life. My life [back home] was a really good one. And here, my whole world was not like this. And the teachers didn’t talk Spanish. I didn’t understand anything, and I felt really bad. I didn’t want to stay here. I wanted to leave. I told my parents that I didn’t want to stay, but if they made this decision then I couldn’t change that.

[Isabel].

As both of these youth demonstrate, disappointment can set in as youth confront the realities of acculturation or adapting to life in the United States. They must learn a new language, cope with changes in their living environment and family systems, and confront changes in their social status. Nevertheless, after the initial culture shock wears off, most of the 283 youth we surveyed believed that the move was the best thing for their families (90%) and themselves (85%). Though they were not always happier in the U.S. than in their home countries (only 45% reported being happier), they felt they had more opportunities in the U.S. and were motivated to succeed. As Carlos summarizes,

At first I didn’t want to go because of the change. Sometimes a person is afraid because it’s another country, it’s another culture, other people. And sometimes it’s as if you fear that but really it’s like the saying goes, “no one becomes a prophet in their own land.” So at times one has to search for other places and that’s what I’ve found in this country, a great opportunity.

[Carlos]

This future orientation, combined with the family orientation discussed below, helped provide youth with the resiliency needed to adapt to life in the U.S.

Encountering Conflicting Values and Nurturing Family Support

One of the first challenges youth faced in adapting to life in the U.S. was the challenge of building a bridge between the culture and values of their home countries and the culture and values of their new communities. Both Fernandina and Carlos expressed the thoughts of many of the adolescents we interviewed:

It’s hard because the things that our parents taught us, they’re not the same as what our teachers or the things that are outside are teaching us right now, so we have to kind of live with it, we have to change but keep what our parents taught us in some way.

[Fernandina]

Call it the friction of two cultures. There’s a friction between “I’m Mexican and I want my traditions to continue being valid” and “I’m American and I want my traditions also to continue being valid.” And when there’s no agreement between the two, that’s where the conflicts [with parents, teachers, and peers] begin.

[Carlos]

According to the adolescents we interviewed, value conflict occurred primarily around prioritizing family responsibilities and goals, being obedient and respectful to parents and other adults, spending time with family, attending church, dressing conservatively, and meeting a curfew. A few adolescent girls also experienced conflict with their parents regarding their relative lack of personal freedom when compared to the boys in their families. Nevertheless, most boys and girls felt that there was far more gender equality in the U.S. and appreciated this. They were also generally happy to assume responsibility for various household tasks and viewed it as a sign of their maturity and their parents’ trust in them.

To help attenuate value conflicts that did occur, it was clear from our interviews with adolescents that parents employed several strategies which emphasized nurturing family support and communication. The youth we interviewed felt that their parents had become better listeners, respected their individuality, and had become more involved in their development. Alonso summarizes the change on his parents’ attitude towards his ideas when making decisions.

Like, a parent here [in the U.S], you know, here if I tell them we should try to do this I mean, they’ll consider it and they’ll probably do it. But I think over there [referring to home country] it [is] like “it doesn’t matter what you think” and [Parents will say] you should do this and this and you better do it.”

[Alonso]

Though living near poverty, the relative financial stability that parents experienced in the U.S. gave youth and their parents more time to engage in family activities. Alonso explained,

I’d say that family here [in the U.S.] is a lot closer-- [more] communicative with each other. I guess it’s because, you know, the parents don’t have to work until late at night to sustain the family, as they would have to do over there [in Mexico]. Like, we would usually go out together to a restaurant or something [on a weekend], which is not something you would do over there [in Mexico] because of the economy and all that.

[Alonso]

Fitting in, Mastering the Language, and Networking with “Americans”

Strong family support provides the security, Latino youth need to embark on the next phase of their adaptation to the U.S. – the process of fitting in by acquiring English language skills and understanding how to negotiate their new communities, especially their school environments. Although most adolescents had some exposure to English and American culture through TV, radio, and conversations with parents or others living in the U.S., most arrived with few English language skills. Like many others, Laura described her experience of not being able to communicate with other people with great frustration.

The moment I left [Mexico] I thought it was going to be fun. And then I got here and I said, "What? What is this?" This was all new to me. It's weird 'cause people were talking in a language I didn't understand, and every time I didn't understand, I thought they were talking about me? I felt very weird because I couldn't communicate with them.

[Laura]

Because of the language barrier, many of the Latino youth we interviewed felt isolated at school. The language barrier also affected their ability to communicate with teachers and consequently, their school performance. This problem was compounded by teachers who relied on bilingual students to translate school rules and homework assignments for Spanish-speaking students. As Isabel shares, the experience is a frustrating one and much can be lost in translation.

The teachers, they would say, “No you have to be in silent lunch.” And the girl translating said, “You have to be in “silent lunch” because you didn’t do your homework.” And I explained that I didn’t know what the homework was because the teacher wrote it on the board. I didn’t understand I didn’t know where it was (written). It was a punishment for not doing homework. But if I don’t understand or I can’t read how can they punish me!

[Isabel]

Though first-generation youth often turn to their bilingual Latino peers for help with translating and navigating the school system, their peers sometimes take advantage of their innocence. Opi shared an example with us,

And people were just racist, and the bad thing about it was that the Hispanic kids were racist! The kids who were born there in Texas [means second generation Hispanics] were like “why are you here!? Blah, blah, blah, blah.” I remember, they [the Hispanic kids] were teaching me English, they were being all nice to me and they taught me to say “I’m crapping in my pants.” And I said it to the teacher and I got in trouble, and everybody was like laughing, you know?

[Opi]

Unable to completely rely on assistance with the language from parents, teachers, or peers, Latino youth quickly prioritize mastering the English language. Alonso told us,

Basically learning the language is a big way of adjusting. Hispanics usually have different customs than what American people do. When you don’t know somebody but [if] you can communicate with that person, then it makes it much easier on you to find friends, get help on something you need, and all that. I think the biggest thing you can do to adjust to living in a different place is first of all to learn the language, hang out first with people you know ‘cause then they’ll introduce you to other people and all that. You learn to fit in by the language. If you talk to people you make friends [and] life is better whenever you have friends, you have somebody to hang out with. So that’s the biggest adjustment, just learning the language. Communication is the main thing.

[Alonso]

As Alonso’s comment suggests, mastery of the English language helps Latino immigrant youth build friendship networks through church and school that they can rely on for additional support. These are most often networks with English-speaking Hispanics and “Americans” – a term used by our participants to refer to white Americans and not Americans of other racial backgrounds. Fernandina explains how these friendship networks help take the place of the extended family left behind in youths’ home countries.

When I go out with my friends I feel really, I feel like I’m kind of, I feel like they’re kind of my family. And that we depend on each other because I just have my family and I just have them. You know my mom and my sister and I just have them. So I guess you know, because I’m away, I’m away from my family I depend a lot on my friends.

[Fernandina]

Although learning English is a priority for immigrant youth trying to ‘fit in’ at school, mimicking the dress and other behavioral patterns of non-Latino Americans is an important additional strategy. Latino boys were especially interested in copying the dress of their African-American peers. As Droopi comments, “Black people….For me, they are really nice people. I like the way they dress and I hang around with a lot of [black] people. So, I’m trying to be like them too.”

Confronting Racism and Shaping a Positive Ethnic Identity

Although Latino youth report many instances of positive race relationships and cases where white and black youth help to show them the ropes and fit in at school, they also report feeling very aware of their ethnicity for the first time and experiencing racism or discrimination. According to our survey data, forty-one percent of adolescents reported experiencing discrimination in the past year. Peer-to-peer harassment was most common (79%) but students often felt that teachers or school administrators and community members also treated them differently because of their race-ethnicity, 25% and 31% respectively. Maria states,

They [the school administrators] always punish us, the Mexicans, and all that. When we were together, there always had to be a policeman because they said we had drugs or pistols or whatever little thing. They always checked only our backpacks, not the Americans’. They treated us bad. It’s really ugly.

[Maria]

Joey demonstrates how his nationality is invoked as a racial slur.

One time I was just there waiting for a friend and this American walks by and, just because I’m standing there, he says “Mexican!” and I’m Mexican and so what? But, they say it in a bad way, like it was something bad, as if saying Mexican was something bad.

[Joey]

To cope with the threat of discrimination, Latino youth embrace their ethnic identity and a strong work ethnic. Erica shares how she embraces her identity as Mexican while focusing on the goal of advancing her future.

I am very proud that I am Mexican. I am very proud of our traditions and want to continue them. You also try to progress…We came here [to the U.S.] to progress and get better.

[Erica]

Isabel explained how important it is for Latino youth to follow their parents’ examples and embrace Latino cultures and customs. She argued that Latino youth should only selectively copy American behaviors.

I don’t know how to explain. We [Latino youth] need to keep our traditions. We don’t have the same opportunities as an American. Americans are a bit more superior. And if [a] door closes [for Latinos], it won’t open again. [Therefore], we [Latinos] have to keep it [the door] open. We have to try. We can’t be like the American totally -- “I am going to do what I want.” No. Latinos have to plan ahead more.…I like how I am. I don’t want to be like an American or like other people. I don’t need that, I feel. This is how I was born and this is how I want to remain. For example, I hear my mom or someone else say, “If they steal a purse you need to steal a purse also?” “If they want to smoke are you going to smoke because that is what they do?” No. And that is certain. You don’t do that just because you want to be like them. It won’t go well. If you have to copy someone, copy the good one, not the bad one. If you see them study, then you study.

[Isabel]

Living in the Shadows and Preparing for the Future

Though the threat of discrimination concerns many of the Latino youth we spoke with, the more salient concern to most was their immigration status. Though they had moved to the U.S. for a better life and economic opportunity, even at the age of 14 many were coming to understand that their legal status could prevent them from realizing their academic aspirations and career goals. Students without legal permanent residency in the U.S. do not qualify for federal student loans and many scholarships; they are required to pay out-of-state tuition to attend most state universities; and in some states (e.g., North Carolina) they are prohibited from attending community colleges. As Fernandina indicates, this can greatly discourage youth.

There’s a lot of Hispanic people that are very discouraged. They don’t think about going to college because they’re probably not legal. Because if you’re not legal, you can’t go to college. So there’s a lot of students out there that finished high school and sometimes they don’t finish it because they’re like, “Why would I finish, if I can’t go to college?” “Why would I do this if people out there are already expecting me to quit because I’m Hispanic?”

[Fernandina]

At the same time, many others continue to be optimistic and hopeful in the face of their uncertain futures. They strive to not only complete but to excel in school and, as Isabel suggested earlier and Alonso suggests below, keep all their options open.

Even for an illegal [immigrant], I think if you put effort into learning the language, doin’ good in school, it’ll be way easier for you to be able to find a job. And then, if there is an opportunity for you to get legalized, you will have the rest of it behind you. I’m not a legal immigrant, I don’t have a visa, I don’t have nothin’. And in school, when I was in the 11th grade, I graduated taking AP Calculus, it was just me and another Hispanic girl, and all the other Hispanics were like “why?” I was like “if there’s ever a chance for me to go [to college], I’ll have that behind me.” I also took a college level course. I always made, my Grade Point Average was like 3.97 or something and I just think that helps you out. If you have the opportunity to go to college, to a community college even or whatever, you know you have that behind you and it’ll help you better yourself.

[Alonso]

DISCUSSION

This study examined how migration can turn an adolescent’s world upside down and how adaptive mechanism that Latino immigrant youth use during migration can help them realign their worlds and adapt to life in the U.S. Guided by cultural-ecological theories of child development, acculturation theory and Sluzki’s stages of migration framework, and risk-resilience and competence perspectives on positive development, we identified three phases of the migration journey: pre-migration, migration, and post-migration. Within each phase, we identified socio-emotional challenges that Latino youth experience and adaptive strategies that they develop to promote their success.

According to Erickson (1968), child development can be observed as a series of stages. At each stage of child development, children confront unique socio-emotional demands and stressors. Successful adaptation to the demands at one stage allows children to develop the skills needed to deal with new demands during the next stage of development. During adolescence, youth develop the skills necessary to make the transition to adulthood by assuming greater independence from parents and power in decision making; initiating new personal, social, and sexual roles and identities; transforming peer relationships into deeper friendships; and developing economic independence (Arnett, 2003; Elliott & Feldman, 1990). The socio-emotional challenges of migration can both promote the development of these skills, and by disrupting social relationships and access to critical resources (e.g., a college education in the U.S.), migration can also hinder the development of these skills.

Immigrant children experience a collection of stressful life events. Consistent with previous research (Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco, 2001; Zuniga, 2002), the stressors that we identified included: (1) separation from parents prior to migration, (2) the physical and emotional stresses of the migration journey, (3) economic hardship both before and after settlement in the United States, (4) conflicting values between their parents and their teachers and peers in school, (5) learning a new language, and (6) social marginalization or discrimination in their new homes.

Despite the inherent risks associated with migration and the challenges they face, first-generation children of immigrants excel with respect to a variety of outcomes compared to their U.S.-born peers (Fuligni & Perreira, 2009). Previous research suggests that their capacities to overcome adversity and the risks associated with migration stem from strong family ties and a sense of family obligation (Fuligni & Pedersen, 2002); a positive ethnic identity (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004; Kiang et al., 2006); a capacity to nurture social networks (Fernandez-Kelley, 1995); and an ability to identify culture brokers (Cooper, Denner, & Lopez, 1999) who help them navigate their new communities. Optimism (Kao & Tienda, 1995) and religious faith (Hagan & Ebaugh, 2003) further strengthen the resiliency of some immigrant youth.

In our interviews, youth discussed many of these resources and adaptive strategies. Furthermore, they demonstrated how migration promoted their transitions to adulthood by fostering both independence (i.e. taking care of one’s self) and interdependence (i.e. responsibility for caring for others; Greenfield, 1992). For example, Alonso and other youth separated from their parents during the pre-migration phase learned the importance of personal responsibility and independence. When their parents left, they reached out to friends and neighbors to develop support networks which helped them cope. At the same time, they learned more about the responsibilities associated with caring for others. They understood that their parents had migrated to assist the family and provide them with income; and they subsequently assumed more responsibility for the well-being of their younger siblings. After migrating to the U.S., they continued to show both their independence and interdependence by learning English and working hard to build friendship networks that would complement their family resources and act as an extended family in the U.S. Though not emphasized in our results, others have also identified how immigrant youth utilize their English skills to assist their parents with medical, legal, and educational matters. In particular, older siblings translate for parents, provide childcare, and assist younger siblings with homework (Dorner, Orellana, & Jiménez, 2008; Fuligni & Penderson, 2002).

In our interviews, youth also discussed the importance of selectively acculturating to American norms of behavior. As predicted by Portes and Rumbaut (2001) and Fuligni (2001), they adopted some American cultural beliefs and behaviors (e.g., English language skills and styles of dress) but also selectively retained other Latino cultures and customs (e.g., a strong work ethic, respect for parental authority, and building and sustaining personal relationships with a broad array of community members). By blending the best of both worlds, they adopted a strategy of adaptation that they believed would best promote their well-being.

Strengths and Limitation

A major strength of this study is that it provides insights into the migration and acculturation experience from the perspective and using the voices of first-generation Latino immigrant youth. Additionally, this study contributes to the small, but growing body of literature on the immigration and acculturation processes experienced by immigrant youth growing up in emerging Latino communities. These Latino communities typically lack the social networks and institutions that facilitate immigrant adaptation to the U.S.; therefore, the experiences of Latino youth settling in these communities may differ from their peers in more established Latino communities such as Los Angeles and Houston.

Though our study has several strengths, it also has limitations that provide fertile ground for additional research to better understand the migration experience and its effects on adolescent development. First, our qualitative interviews focused on adolescents enrolled in high school. However, some adolescents migrate to the U.S. to work and never enroll in high school while others drop out of high school as soon as legally possible (Fry, 2003). Second, the majority of youth participating in our qualitative interviews were of Mexican origin and from low-income families who migrated primarily for economic reasons. The experiences of immigrant youth and families who migrate for educational reasons, who have substantial socio-economic resources, or who migrate in response to civil strife and political violence can differ dramatically from the experiences of the youth we interviewed (Zuniga, 2002). More research is needed to understand the experiences of these important subsets of first-generation immigrant youth and the way these experiences shape their development. Third, our research was cross-sectional and based entirely in the U.S. Thus, we are not able to observe the process of individual change over time or in comparison to normative development of similar youth in their countries of origin. As argued elsewhere (e.g., Fuligni, 2001), to develop a more comprehensive understanding of adolescence and the transition to adulthood for immigrant youth, we need more transnational, comparative longitudinal data on them.

CONCLUSION

This study used in-depth interview data from the LAMHA project to gain an understanding of how migration shapes the normative development of Latino youth (ages 14–18) growing up in the U.S. Southeast. Through our interviews, we show how migration can be understood as a process that starts in youths’ home countries and unfolds over time (Zuniga, 2002). The first phase of adolescent migration takes place in youths’ home countries when some youth are left behind while parents sojourn to the U.S. to earn money. Similarly, the first phase of acculturation takes place in youths’ home countries when they are exposed to the language and cultures of the U.S. through TV shows, radio, and conversations with family members currently living in the U.S. or who have recently returned. The second phase of migration captures the transition from the country of origin to the country of destination. The third phase of migration focuses on the adjustments that occur in the country of destination. Thus, research on migration and acculturation processes must traverse international boundaries and begin to explore the onset of migration and acculturation experiences in youths’ home countries.

Through our interviews, we also learned which risks associated with migration were most salient to Latino adolescents and what types of strategies adolescents and their families developed to cope with these risks. The Latino immigrant youth we spoke with were extremely cognizant of the challenges they faced and quite resourceful. Although migration certainly posed risks for them, the challenges of migration also created opportunities for them to both establish their independence and to develop the relational skills needed to be productive adults who contribute to their families and communities. Intervention programs designed to help youth and their families transition into their lives in the U.S. should take into account adolescents’ perspectives and build upon the strategies that youth and their families already employ.

Acknowledgments

The LAMHA project was funded by a grant from the William T. Grant Foundation and directed by Krista M. Perreira and Mimi V. Chapman. Persons interested in obtaining LAMHA contract use data should see http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/lamha for further information. This analysis was also supported in part by the Russell Sage Foundation Visiting Scholar Program, the UNC Lineberger Cancer Control Education Program (R25 CA057726) and the Society for Public Health Education Student Scholarship. The authors would also like to express our appreciation to Tina Siragusa and Sandy Chapman for their assistance with interviewing the adolescents, and to Stephanie Potochnick for her assistance with analysis of the survey data. Most importantly, we thank all the schools, immigrant families, and adolescents who participated in our research project.

Biographies

Linda Ko is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Her research focuses, in part, on the development of cancer prevention and intervention programs to improve Latino health.

Krista M. Perreira is an associate professor of public policy at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She studies the well-being of immigrant youth and inter-relationships between migration, health, and social policy. Her immigration research has been supported by the William T. Grant Foundation, Russell Sage Foundation, and the Foundation for Child Development.

Footnotes

Schools in North Carolina were grouped into two strata – urban and rural – and were randomly selected for participation in the study based in proportion to the number of Latino students enrolled in the school. A roster of all youth who self-identified as Hispanic/Latino or had Hispanic/Latino surnames was prepared by each randomly selected school. These youth were then contacted and screened for eligibility. Only youth born abroad in Latin America or the Caribbean (i.e. Cuba, the Dominican Republic, or the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico) were eligible for inclusion in the study and only one youth per household could participate. We screened 704 households; 58% included an eligible adolescent; 325 (80% of those eligible) indicated an interest in participating. Primarily due to scheduling difficulties, we interviewed only a total of 283 caregiver-youth dyads. Thus, our final response rate was 69%. Those who refused to participate almost uniformly (80 out of 83) indicated that they did not have sufficient time off work to complete a 2-hour interview with their child.

References

- Arnett J. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2003;100:63–75. doi: 10.1002/cd.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CR, Denner J, Lopez EM. Cultural brokers: Helping Latino children on pathways toward success. The Future of Children. 1999;9:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner LM, Orellana MF, Jiménez R. Adolescents language brokering and the development of immigrant: "It's one of those things that you do to help the family". Journal of Adolescent Research. 2008;23:515–543. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott GR, Feldman SS. Capturing the adolescent experience. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge: Harvard Press; 1990. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Kelly MP. Social and cultural capital in the urban ghetto: Implications for the economic sociology of immigration. In: Portes A, editor. The economic sociology of immigration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1995. pp. 213–247. [Google Scholar]

- Fry R. Hispanic youth dropping out of U.S. schools: Measuring the challenge (Pew Hispanic Center Report) Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. A comparative longitudinal approach to acculturation among children from immigrant families. Harvard Educational Review. 2001;71:566–578. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Pedersen S. Family obligation and the transition to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:856–868. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Perreira KM. Immigration and adaptation. In: Villarruel FA, Gustavo C, Grau JM, Azmitia M, Cabrera NJ, Chahin TJ, editors. Handbook of US Latino Psychology: Developmental and community-based perspectives. Thousand Oaks, LA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2009. pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, Vásquez-García H. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson M. Accommodation without assimilation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Fabrett FC, Knight GP. Acculturation, Enculturation, and the Psychological Adaptation of Latino Youth. In: Villarruel FA, Gustavo C, Grau JM, Azmitia M, Cabrera NJ, Chahin TJ, editors. Handbook of US Latino Psychology: Developmental and community-based perspectives. Thousand Oaks, LA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2009. pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield PM. Independence and interdependence as developmental scripts: Implications for theory, research, and practice. In: Greenfield PM, Cocking RR, editors. Cross-cultural roots of minority child development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Ebaugh HR. Calling upon the sacred: Migrants’ use of religion in the migration process. International Migration Review. 2003;37:1145–1162. [Google Scholar]

- IPUMS. "IPUMS On-line Data Analysis System." Minneapolis: Minnesota Population Center. 2000 Available at: http://usa.ipums.org/usa/sda/

- Kao G, Tienda M. Optimism and achievement: The educational performance of immigrant youth. Social Science Quarterly. 1995;76:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Yip T, Gonzales-Backen M, Witkow M, Fuligni AJ. Ethnic identity and the daily psychological well-being of adolescents from Mexican and Chinese backgrounds. Child Development. 2006;77:1338–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt MJ, Lane JD, Levitt J. Immigration stress, social support, and adjustment in the first post-migration year: An intergenerational analysis. Research in Human Development. 2005;2:159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Durand J, Malone N. Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican immigration in an era of economic integration. New York: Russell Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. ualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publication, Inc; 1994. Q. [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T. AtlasTi User’s Manual and Reference. Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. Immigrant and involuntary minorities in comparative perspective. In: Gibson MA, Ogbu JU, editors. Minority status and schooling: A comparative study of immigrant and involuntary minorities. New York: Garland; 1991. pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira K, Chapman M, Potochnick S, Ko L, Smith T. Migration and mental health: Latino youth and parents adapting to life in the American south. Carolina Population Center, NC. [Online] 2008 www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/lamha/publications.

- Perreira K, Chapman M, Stein G. Becoming an American parent: Overcoming challenges and finding strength in a new immigrant Latino community. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1383–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. Dramatizing data: A primer. Qualitative Inquiry. 2003;9:218–236. [Google Scholar]

- Schoon I. Risk and resilience adaptations in changing times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco M. Children of immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Suro R, Tafoya S. Dispersal and concentration: Patterns of Latino residential settlement. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Fine MA. Examining a model of ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the U.S. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26:36–59. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The 2006 HHS Poverty Guidelines. 2006 Available at http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/06poverty.shtml.

- U.S. Census. Population Projections of the United States by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 1995 to 2050. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Williams SL, Alvarez SD, Andrade Hauck KS. My name is not María: Young Latinas seeking home in the heartland. Social Problems. 2002;49:563–584. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Seidman E. Competence among urban adolescents in poverty: Multiple forms, contexts, and developmental processes. In: Montemayor R, Adams GR, Gullotta TP, editors. Advances in adolescent development: Vol. 10: Adolescent diversity in ethnic, economic, and cultural contexts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Bankston CL. Growing Up American: How Vietnamese Children Adapt to Life in the United States. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga ME. Latino immigrants: Patterns of survival. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2002;5:137–155. [Google Scholar]