Abstract

A U5 snRNP protein, hPrp8, interacts closely with the GU dinucleotide at the 5′ splice site (5′SS), forming a specific UV-inducible cross-link. To test if this physical contact between the 5′SS and the carboxy-terminal region of Prp8 reflects a functional recognition of the 5′SS during spliceosome assembly, we mutagenized the corresponding region of yeast Prp8 and screened the resulting mutants for suppression of 5′SS mutations in vivo. All of the isolated prp8 alleles not only suppress 5′SS but also 3′SS mutations, affecting the second catalytic step. Suppression of the 5′SS mutations by prp8 alleles was also tested in the presence of U1–7U snRNA, a predicted suppressor of the U+2A mutation. As expected, U1–7U efficiently suppresses prespliceosome formation, and the first, but not the second, step of U+2A pre-mRNA splicing. Independently, Prp8 functionally interacts with both splice sites at the later stage of splicing, affecting the efficiency of the second catalytic step. The striking proximity of two of the prp8 suppressor mutations to the site of the 5′SS:hPrp8 cross-link suggests that some protein:5′SS contacts made before the first step may be subsequently extended to accommodate the 3′SS for the second catalytic step. Together, these results strongly implicate Prp8 in specific interactions at the catalytic center of the spliceosome.

Keywords: U5 snRNP protein, Prp8, 5′ splice site, spliceosome, catalytic center

Accurate selection of splice sites, one of the critical steps in pre-mRNA splicing, is necessary for correct removal of intron sequences. The early recognition of the intron/exon borders leads to proper positioning of selected splice sites within the spliceosome and precise definition of phosphodiester bonds that participate in splicing. Despite minor differences, the mechanism of splice site recognition, spliceosome assembly, and splicing is remarkably conserved between yeast and mammals (Moore et al. 1993; Burge et al. 1999; Nilsen 1998). In both systems, recognition of the 5′ splice site (5′SS) sequence is a complex, at least two-step process that is initiated by the binding of U1 snRNP to the 5′SS. In the resulting commitment complex (termed complex E in the HeLa cell system) the conserved 5′SS consensus sequence is paired with the 5′ end of U1 snRNA. The involvement of this pairing in the 5′SS recognition has been confirmed in both yeast and mammalian systems using both genetic and biochemical methods (for review, see Rosbash and Séraphin 1991; Siliciano and Guthrie 1988). At later stages in the process, when U4/U5/U6 snRNP joins prespliceosome containing U2 snRNP bound to the branch site (complex A in mammalian systems), 5′SS:U1 snRNA pairing is disrupted and replaced with the 5′SS:U6 snRNA duplex (Kandels-Lewis and Séraphin 1993; Konforti et al. 1993; Lesser and Guthrie 1993a). Although molecular mechanisms responsible for this transition are currently unknown, yeast DEAD-box factor Prp28 has been implicated in this process (Staley and Guthrie 1999).

Both U2 and U6 snRNAs have been implicated in interactions with the 5′SS at the catalyitic center (Luukkonen and Séraphin 1998a,b). Specific 5′SS:U6 snRNA base-pairing interaction can form even in the absence of U2 snRNP (Konforti and Konarska 1994); however, components of U5 snRNP are necessary for proper positioning of the 5′SS within the spliceosome. In particular, base-pairing between the central loop of U5 snRNA and exon sequences may contribute to 5′SS recognition (Newman and Norman 1992; Teigelkamp et al. 1995). Furthermore, in vitro experiments in HeLa cell extracts revealed that a U5 snRNP component, hPrp8 (also termed p220), closely interacts with the 5′SS, forming a UV cross-link with the highly conserved GU dinucleotide at the 5′SS junction (Reyes et al. 1996). Moreover, minor modifications of the uridine residue (rU to rT or 5IdU) at the GU dinucleotide affect interaction of hPrp8 with the 5′SS and interfere with splicing (Reyes et al. 1996). Interestingly, a small subset of both U2- and U12-type pre-mRNAs is characterized by AU-AC, rather than GU-AG, dinucleotides at the ends of the intron (Dietrich et al. 1997; Sharp and Burge 1997). The fact that the same U5 snRNP and thus most likely the same Prp8 are implicated in splicing of both the major and minor classes of introns (Tarn and Steitz 1996; Luo et al. 1999) suggests that Prp8 may contribute to recognition of uridine at the 5′SS (U+2). Thus, hPrp8 is implicated in recognition of the 5′SS and its proper positioning within the spliceosome before the first step of splicing. Prp8, which is the largest (279 and 273 kD for yeast and human proteins, respectively) component of U5 snRNP (Anderson et al. 1989; Hodges et al. 1995; Luo et al. 1999) previously has been implicated in multiple contacts within the spliceosome. It interacts closely with U5 snRNA (Dix et al. 1998), as well as with the 5′SS, branch site, polypyrimidine (PPY) tract, and the 3′SS (Wyatt et al. 1992; MacMillan et al. 1994; Teigelkamp et al. 1995; Umen and Guthrie 1995; Reyes et al. 1996; Chiara et al. 1997), thus representing the only spliceosomal factor known to directly interact with all pre-mRNA sequence elements important for splicing. Together with U6 snRNA, Prp8 represents one of the most highly conserved spliceosomal factors (86% identity between Caenorhabditis elegans and human, and 62% identity between yeast and human proteins). The high level of conservation spans a wide range of organisms, from humans, nematodes, plants, yeast, to trypanosomes.

Because of the remarkable conservation of Prp8, its apparently central position within the spliceosome, and its direct interaction with the GU dinucleotide at the 5′SS, we have mapped the precise location of the 5′SS:hPrp8 UV cross-link (Reyes et al. 1999). Interestingly, this cross link is located within the carboxy-terminal segment of the human protein (amino acid positions 1894–1898), near the previously defined PPY tract recognition domain within yeast Prp8 (Umen and Guthrie 1995). The carboxy-terminal region in yPrp8 has been also implicated in genetic interactions with the 3′SS (Umen and Guthrie 1996) and U4 snRNA (Kuhn et al. 1999), suggesting that it may be involved in multiple interactions with U4/U6 snRNAs, PPY tract, and both splice sites.

To test the possibility that the carboxy-terminal segment of Prp8 is involved in functional interactions with the GU dinucleotide at the 5′SS, we mutagenized the corresponding region of yPRP8 and screened the resulting mutants for suppression of 5′SS mutations in vivo using the ACT1–CUP1 reporter system (Lesser and Guthrie 1993b). We have isolated several alleles of prp8 that suppress U+2A mutation at the 5′SS. The same prp8 alleles also suppress mutations at the 3′SS, affecting the second step of splicing in vivo. To further analyze function of Prp8 at the second step of splicing, we introduced a suppressor U1–7U snRNA that restores U1 snRNA:U+2A 5′SS pairing and is thus expected to correct 5′SS mutation defects at the early stages in the reaction. U1–7U significantly elevates prespliceosome levels and suppresses the first, but not the second, step of splicing. Except for the two strongest prp8 alleles, addition of U1–7U does not enhance suppression by prp8 alleles, indicating that in most cases prp8 suppression is not limited by the inefficient first step of splicing. Together, these results indicate that Prp8 is involved in functional interactions with both splice sites at the second step of splicing, suggesting that this protein represents an important component of the spliceosomal catalytic center.

Results

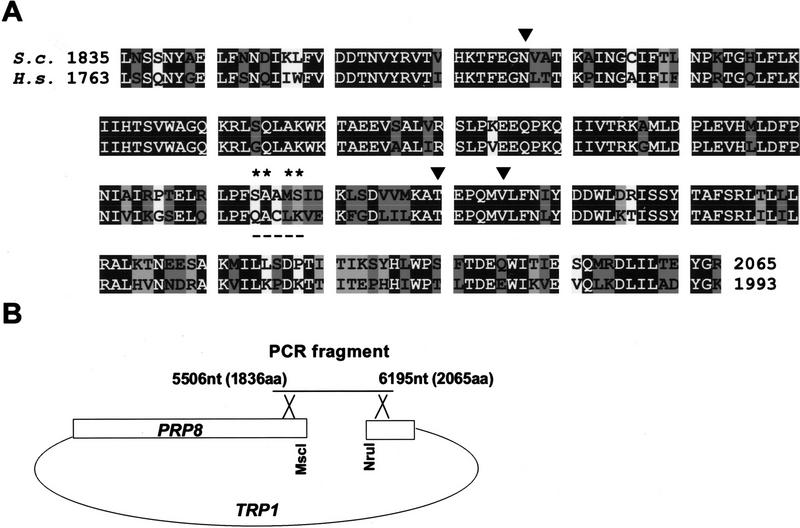

Region-specific mutagenesis of the PRP8 gene

Because of the large size of yeast PRP8, four separate, individually mutagenized segments of the gene previously were subjected to genetic analysis (Umen and Guthrie 1996). To concentrate on the protein region implicated in interactions with the 5′SS, we have restricted our analysis to the carboxy-terminal segment of yPrp8. Based on the mapped site of the cross-link between the 5′SS and hPrp8 (amino acids 1894–1898; Reyes et al. 1999) we identified the homologous yPrp8 sequence (amino acids 1966–1970) and mutagenized a 690-nucleotide segment of the yPRP8 gene (amino acids 1836–2065) spanning this site (Fig. 1A). The mutagenic PCR procedure increased the error rate of Taq polymerase in a relatively unbiased fashion (Caldwell and Joyce 1992), resulting in ∼0.66% mutation per position. This rate of mutagenesis did not allow us to generate all possible mutations in the 690-nucleotide fragment but was suitable for random, selected probing of the entire segment. In addition, we fully randomized two pairs of amino acids that correspond to the mapped site of the 5′SS:hPrp8 cross-link (Reyes et al. 1999), producing XXAMS and SAAXX pools from the wild type 1966SAAMS1970 sequence (indicated by an asterisk in Fig. 1A). The libraries of mutated sequences were amplified using overlapping PCR and introduced into the yPRP8 gene by homologous recombination in vivo (Fig. 1B; Materials and Methods; see Umen and Guthrie 1996).

Figure 1.

Preparation of the mutagenized libraries of the S. cerevisiae PRP8 gene. (A) Alignment of the carboxy-terminal segment of Prp8 from S. cerevisiae (EMBL Z24732) and Homo sapiens (GenBank accession no. AF092565). The carboxy-terminal segment of yPrp8 (5506–6195 nucleotides, amino acids 1836–2065) was used in mutagenic PCR to create a random library. In addition, two pairs of amino acids (*) flanking the mapped site of the 5′SS:hPrp8 cross-link (amino acids 1966–1970, underlined) were fully randomized to create two other libraries. Identical (solid), highly similar (dark-shaded), and similar (light-shaded) positions are indicated. (▾) Positions corresponding to the identified suppressor mutations. (B) Generation of mutant prp8 alleles. Wild-type PRP8 cleaved with NruI, and MscI was recombined in vivo with appropriate PCR fragments.

Screening for prp8 suppressor alleles of 5′SS mutations

The libraries of mutagenized yPRP8 were screened in yeast strains containing an ACT1–CUP1 fusion reporter gene. Splicing of the ACT1 intron present in this reporter controls expression of the CUP1 gene, which encodes a copper-chelating metallothionein (Karin et al. 1984). Thus, cell growth in the presence of Cu2+ in the medium is proportional to the level of correct splicing of the ACT1 intron (Lesser and Guthrie 1993a,b). For the initial screen of PRP8 mutants we used an ACT1–CUP1 reporter containing a U+2A mutation at the 5′SS (Fig. 2A, position +2 of the intron), screening ∼3000 transformants for each library. Although cells containing wild-type PRP8 and the U+2A 5′SS reporter grow poorly in the presence of 0.025 mm CuSO4, some of the transformants containing the mutagenized PRP8 gene were able to grow in 0.05 mm Cu2+ (data not shown). The selected mutants show a dominant phenotype, as this test was performed in the presence of the wild-type PRP8 gene on a low copy number plasmid.

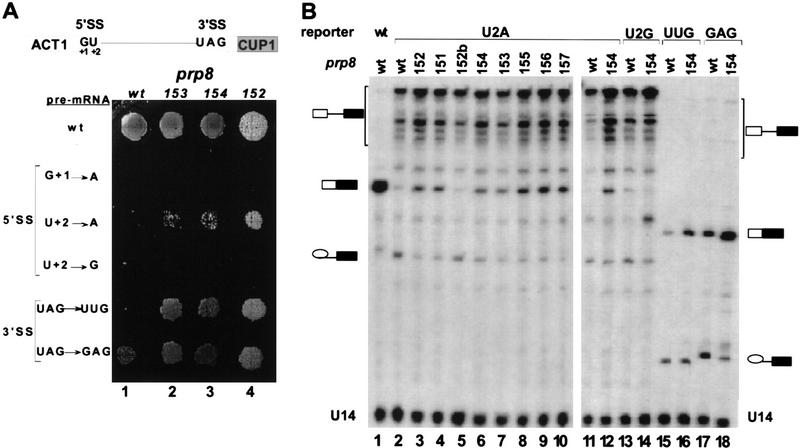

Figure 2.

prp8 alleles suppress mutations at the 5′SS and 3′SS in vivo. (A) Copper growth phenotypes of wild-type and selected prp8 suppressor strains in the presence of ACT1–CUP1 reporters containing 5′SS and 3′SS mutations, as indicated. (B) Primer extension analysis of in vivo splicing of ACT1–CUP1 reporter containing selected 5′SS and 3′SS mutations. Extension products generated with wild-type PRP8 (lanes 1,2,11,13,15,17) or prp8 suppressors (lanes 3–10,12,14,16,18, as indicated) in the presence of wild-type (lane 1), U+2A (lanes 2–12), U+2G (lanes 13,14), UAG → UUG (lanes 15,16), or UAG → GAG (lanes 17,18) reporters were resolved on a 7% polyacrylamide/8 m urea gel. Positions of U14 snRNA internal control, pre-mRNA, mRNA, and lariat intermediate products are indicated. Note that sequence differences among various reporters result in distinct mobilities of their extension products.

From the initial pool of colonies capable of growth in 0.05 mm Cu2+ we selected the strongest alleles that support growth even in the presence of 0.1 mm Cu2+ (Table 1). The prp8-151, prp8-153, and prp8-155 alleles were isolated from the random mutagenesis PCR library, whereas prp8-152 and prp8-154 were derived from libraries containing two randomized amino acid positions (SAAXX and XXAMS, respectively). None of these alleles was able to suppress the G+1A mutation, indicating that not all mutations at the 5′SS are equally suppressed. In addition to U+2A, a very low but detectable level of suppression was also observed in the presence of the U+2G reporter (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly however, the same alleles can also suppress mutations at the 3′SS (Fig. 2A, UAG → UUG and UAG → GAG; data not shown). The obtained level of suppression is moderate; the selected prp8 alleles do not restore growth to the level typical of the wild-type reporter, which is capable of growth even in the presence of 1.75 mm CuSO4. These results indicate that in addition to Prp8 other spliceosomal components also interact with the 5′SS and 3′SS, precluding complete suppression by Prp8 alone.

Table 1.

Mutations in yPrp8 identified in this study

| Allele

|

Mutation(s)

|

Growth in Cu2+ (mm)

|

|---|---|---|

| prp8-151 | N1869D | 0.1 |

| prp8-152 | N1869D, S1970R | 0.1 |

| prp8-153 | T1982A | 0.1 |

| prp8-154 | T1982A, SA1966/7AG | 0.1 |

| prp8-155 | T1982A, V1987Aa | 0.1 |

| prp8-156 | N1869D, T1982A | 0.2 |

| prp8-157 | N1869D, S1970R, T1982A, V1987Aa | 0.2 |

The first two columns show the allele designation and the mutations identified by sequencing 3′-terminal regions of each mutant. Mutations responsible for the suppressor phenotype are shown in boldface type, and their ability to grow in the presence of CuSO4 is indicated in the third column.

The V1987A mutation has not been isolated and tested in the absence of other mutations. However, because of its strong effect on splicing, we consider it a likely candidate for a bona fide suppressor mutation.

Sequence analysis of the selected prp8 alleles revealed the identity of mutations responsible for the observed phenotypes (Fig. 1A, ▾; Table 1). Only two alleles, prp8-151 and prp8-153, contain single mutations—N1869D and T1982A, respectively—whereas other alleles contain two or more mutations. As expected, both prp8-152 and prp8-154 contain mutations within randomized 1966SAAMS1970, changing it to SA1966/7AG and S1970R, respectively. All prp8 alleles described in this work are haploviable, indicating that they also support splicing of wild-type pre-mRNAs.

As expected, mutations present in prp8-151-5 alleles are located in the region of Prp8 implicated in the 5′SS:hPrp8 interaction (Reyes et al. 1999). The N1869D mutation is located ∼100 amino acids upstream of the site that corresponds to the mapped 5′SS:hPrp8 cross-link (amino acids 1966–1970), whereas the T1982A and V1987A mutations are located <20 amino acids downstream of that site. The close proximity of these sites to the mapped site of the 5′SS:hPrp8 cross-link suggests that this region of Prp8 may be directly involved in a functional interaction with the 5′SS in both mammalian and yeast systems.

Analysis of in vivo splicing by primer extension assays

To confirm the splicing-dependent effect of selected prp8 suppressor alleles, the wild-type PRP8 copy was removed from these strains and primer extension analysis of endogenous ACT1–CUP1 transcripts of the U+2A reporter was carried out (Fig. 2B). Using a DNA primer complementary to the second exon of ACT1, extended products corresponding to unspliced pre-mRNA (∼510 nucleotides), spliced exons (∼200 nucleotides), and lariat intermediates (143 nucleotides, up to the branch site) can be detected. Splicing of the reporter can be monitored by determining steady-state levels of pre-mRNA (P), lariat intermediate (L) and spliced mRNA (M) (Jacquier et al. 1985). The efficiency of the first and second step of splicing is monitored by calculating M+L/P and M/L ratios, respectively (Table 2), although these values may be affected by different stabilities of various splicing intermediates and products in vivo. As expected, although the wild-type reporter RNA is spliced almost completely (86.5%) in the presence of wild-type Prp8 (Fig. 2B, lane 1), splicing of the U+2A reporter is impaired severely under these conditions (5.4% spliced mRNA; Fig. 2B, lane 2; Table 2). In the presence of suppressor prp8 alleles, however, the spliced mRNA signal becomes easily detectable (Fig. 2B, lanes 3,4,6–10). The effect of prp8 alleles on the second step of splicing (measured as M/L) correlates well with their growth in the presence of Cu2+ in the media. The prp8-151 and prp8-152 alleles, both containing N1869D, increase splicing four- to fivefold as compared to the wild-type level (Table 2), whereas the isolated S1970R mutation (termed prp8-152b) does not affect splicing (Fig. 2B, lane 5). However, some mutations that do not exhibit suppressor phenotype by themselves (S1970R and SA1966/7AG), display a modest positive effect in the presence of another suppressor mutation. Finally, the M/L ratio increases twofold between prp8-155 and prp8-153, indicating that V1987A contributes significantly to suppression of U+2A. The observed suppression of splicing affects primarily the second step, as no significant reduction in the level of unspliced pre-mRNA and no accumulation of lariat intermediates can be detected in these reactions. M+L/P that measures the efficiency of the first step of splicing is not significantly affected (0.8- to 1.1-fold over wild-type) by the selected prp8 alleles (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phenotypes of prp8-151-7 alleles—primer extension analysis

| Prp8/reporter/U1

|

%P

|

%L

|

%M

|

M+L/P (step 1)

|

M/L (step 2)

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt/U2A/− | 84.1 ± 1.8 | 10.5 ± 1.3 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 151/U2A/− | 85.2 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 9.9 ± 0.3 | 0.92 ± 0.3 | 3.93 ± 0.2 |

| 152/U2A/− | 85.2 ± 1.6 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 10.9 ± 1.3 | 0.91 ± 0.2 | 5.34 ± 0.2 |

| 152b/U2A/− | 86.4 | 9.2 | 4.4 | 0.83 | 0.93 |

| 153/U2A/− | 84.6 ± 1.2 | 6.7 ± 1.1 | 8.7 ± 1.5 | 0.96 ± 0.1 | 2.60 ± 0.8 |

| 154/U2A/− | 84.4 ± 3.0 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 9.8 ± 2.2 | 0.98 ± 0.2 | 3.29 ± 0.8 |

| 155/U2A/− | 82.6 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 12.5 ± 0.3 | 1.11 ± 0.1 | 4.70 ± 0.8 |

| 156/U2A/− | 83.4 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 12.1 ± 0.9 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 5.23 ± 1.4 |

| 157/U2A/− | 86.3 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 10.0 ± 1.0 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 5.12 ± 1.0 |

| wt/wt/− | 9.1 ± 1.8 | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 86.5 ± 2.0 | 52.84 ± 8.6 | 38.22 ± 9.0 |

| wt/U2A/U1–7U | 61.8 ± 2.8 | 27.2 ± 1.7 | 11.0 ± 1.4 | 3.27 ± 0.4 | 0.79 ± 0.1 |

| 151/U2A/U1–7U | 59.5 ± 0.3 | 11.5 ± 1.7 | 29.0 ± 2.0 | 3.60 ± 0.05 | 4.90 ± 0.1 |

| 152/U2A/U1–7U | 65.3 ± 3.8 | 12.8 ± 2.2 | 21.2 ± 2.4 | 2.81 ± 0.5 | 3.22 ± 1.4 |

| 153/U2A/U1–7U | 61.0 ± 3.0 | 15.2 ± 1.8 | 23.8 ± 1.6 | 3.38 ± 0.5 | 3.04 ± 0.4 |

| 154/U2A/U1–7U | 64.2 ± 3.2 | 12.7 ± 3.3 | 23.1 ± 0.7 | 2.95 ± 0.4 | 3.54 ± 0.8 |

| 155/U2A/U1–7U | 59.4 ± 3.3 | 14.6 ± 1.7 | 26.0 ± 2.8 | 3.51 ± 0.5 | 3.46 ± 0.6 |

| 156/U2A/U1–7U | 56.3 ± 5.3 | 8.7 ± 2.0 | 35.0 ± 4.4 | 4.11 ± 0.9 | 7.82 ± 1.9 |

| 157/U2A/U1–7U | 65.4 ± 3.9 | 6.8 ± 1.6 | 27.8 ± 3.4 | 2.80 ± 0.5 | 7.95 ± 1.9 |

| wt/wt/U1–7U | 7.8 ± 1.4 | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 87.8 ± 0.2 | 62.52 ± 12.6 | 38.80 ± 9.0 |

| wt/U2A/U1–wt | 88.2 ± 0.4 | 8.0 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.95 ± 0.1 |

| 155/U2A/U1–wt | 87.3 ± 2.1 | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 0.93 ± 0.1 | 4.35 ± 0.6 |

| 156/U2A/U1–wt | 81.0 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.1 | 14.8 ± 0.4 | 1.26 ± 0.04 | 6.40 ± 0.1 |

| 157/U2A/U1–wt | 85.3 ± 0.6 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 11.0 ± 0.8 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 5.78 ± 0.6 |

| wt/wt/wt | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 2.0 | 90.0 ± 2.1 | 87.51 ± 1.2 | 40.70 ± 1.6 |

| wt/U2G/− | 86.5 ± 3.5 | 9.1 ± 2.7 | 4.5 ± 0.8 | 0.83 ± 0.3 | 0.96 ± 0.1 |

| 153/U2G/− | 91.9 ± 1.8 | 5.3 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 0.47 ± 0.1 | 1.06 ± 0.4 |

| wt/UUG/− | 36.5 | 37.5 | 26.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 153/UUG/− | 21.1 | 31.3 | 47.5 | 2.15 | 2.19 |

| wt/GAG/− | 23.4 | 34.9 | 41.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 153/GAG/− | 17.3 | 14.3 | 68.4 | 1.46 | 4.00 |

The identity of the prp8, ACT1–CUP1 reporter, and U1 snRNA genes is indicated in the first column. The second to fourth columns show percent distribution of pre-mRNA (P), lariat intermediate (L), and spliced exons (mRNA, M). The fifth and sixth columns display the efficiency of the first and second steps as M + L/P and M/L ratios, respectively. The primer extension data were obtained from 3–10 independent experiments (except for values provided without error bars, which represent a single experiment). The values in columns five and six are normalized to data obtained for the corresponding reporter in the presence of the wild-type PRP8, and in the absence of additional U1 snRNA genes.

Therefore, primer extension analysis confirmed three point mutations within Prp8 that confer significant levels of suppression of the U+2A 5′SS mutant template in vivo (Fig. 1A, ▾). The first of these mutations, N1869D, is located ∼120 amino acids upstream of the two other mutations, T1982A and V1987A, that are positioned near the mapped site of the 5′SS:hPrp8 cross-link. To test whether the selected mutations have additive effects, additional prp8 alleles were prepared in which individual suppressor mutations were combined (prp8-156 and prp8-157; Table 1). The suppressor phenotype of these alleles, as measured either by growth in the presence of Cu2+ or by primer extension, was stronger than that exhibited by any one of the parent alleles. As in the case of prp8-151-5 alleles, suppression affects primarily the second step of splicing.

Consistent with the results of growth in the presence of copper, splicing of the analogous U+2G 5′SS reporter is not significantly improved by the prp8-154 allele (Fig. 2B, lanes 13,14), indicating a specific suppression of the U+2A 5′SS mutation. However, splicing of two reporters containing UAG → UUG and UAG → GAG mutations at the 3′SS is improved considerably (Fig. 2B, lanes 15–18). Again, suppression affected primarily the second step of splicing, as no significant changes in the accumulation of the lariat intermediate were observed under these conditions (Table 2). Similar results were obtained for other prp8 alleles (data not shown).

In vitro splicing of selected prp8 suppressor alleles

Yeast whole cell extracts were prepared from strains containing various prp8 suppressors. For these experiments, the wild-type prp8 copy was removed, leaving the suppressor prp8 allele as the sole copy of the gene. First, extracts were tested for splicing activity using ACT1 pre-mRNA carrying different mutations at the 5′SS and 3′SS. Splicing efficiency of wild-type pre-mRNA in these extracts is comparable to that observed with wild-type Prp8, indicating that suppressor mutations in Prp8 do not significantly affect the utilization of wild-type splice site signals (Fig. 3, lanes 1,4). As expected, splicing of the 3′SS UAG → UUG pre-mRNA is reduced in the wild-type Prp8 extract (Fig. 3, lane 3). In particular, the second step of splicing is inhibited, leading to accumulation of lariat intermediates in the reaction (Ruskin and Green 1985; Fouser and Friesen 1986; Vijayraghavan et al. 1986). Although splicing efficiency of UAG → UUG pre-mRNA in prp8 suppressor extracts is still reduced, the ratio of accumulated lariats to lariat intermediates (2- to 3.5-fold over the wild-type level) indicates that the second step of splicing is more efficient than in wild-type extracts (Fig. 3, cf. lanes 3 and 6–14). In contrast, splicing of U+2A pre-mRNA cannot be detected in these extracts (Fig. 3, lanes 2,5). Furthermore, assembly of splicing complexes is practically undetectable in these reactions (see Fig. 4C, lanes 1–3; data not shown). Thus, although suppression of the second step of splicing can be detected in vitro for UAG → UUG 3′SS pre-mRNAs, splicing of U+2A pre-mRNAs is undetectable under these conditions (data not shown).

Figure 3.

In vitro suppression of the 3′SS mutation by selected prp8 alleles. Wild-type (lanes 1,4), U+2A (lanes 2,5), and UAG → UUG (lanes 3,6–16) pre-mRNAs were incubated in extracts prepared from wild-type PRP8 (lanes 1–3,15,16) or selected prp8 allele (lanes 4–14, as indicated) strains. Positions of pre-mRNA, lariat intermediate, and lariat products are indicated.

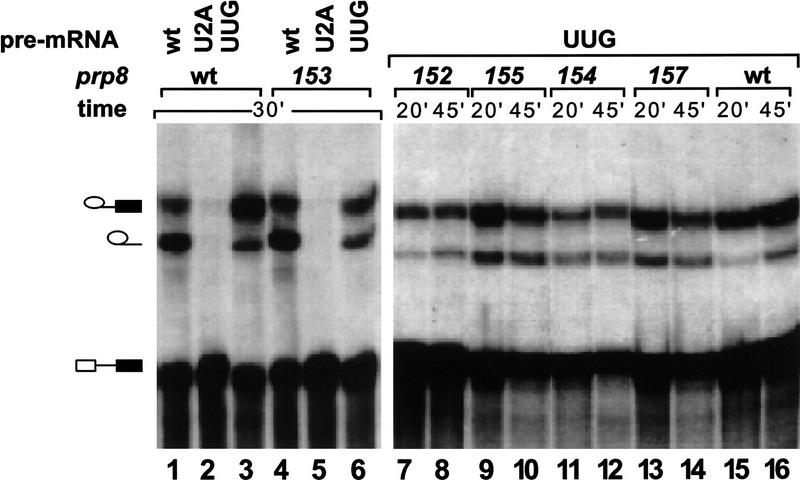

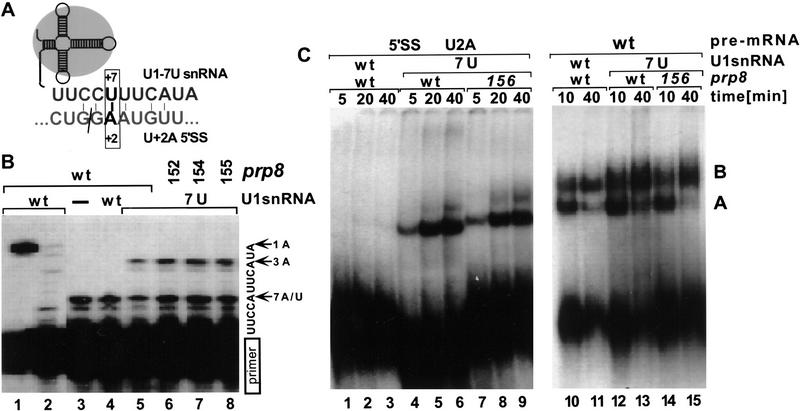

Figure 4.

Suppressor effects of U1–7U snRNA. (A) Schematic representation of the U+2A 5′SS and U1–7U snRNA pairing interaction. (B) Primer extension analysis of total RNA isolated from yeast extracts containing wild-type (lanes 1–5) or suppressor prp8-152, prp8-154, and prp8-155 (lanes 6–8). The analyzed strains contained in addition a wild-type U1 (lanes 1,2,4) or suppressor U1–7U (lanes 5–8) snRNA gene. To detect both the wild-type and U1–7U snRNAs, primer extension analysis was carried out in the presence of all dNTPs (lane 1), dGTP and dATP (lane 2) or dGTP, dATP, ddTTP (lanes 3–8). In the presence of ddTTP, the 5-nucleotide extension corresponds to a wild-type snRNA, and a 9-nucleotide extension to a U1–7U snRNA. (C) In vitro splicing reactions using U+2A (lanes 1–9) and wild-type (lanes 10–15) pre-mRNA were carried out in the presence of extracts prepared from the wild-type PRP8 (lanes 1–6,10–13) or prp8-156 strain (lanes 7–9,14,15) containing wild-type (lanes 1–3,10,11) or U1–7U snRNA (lanes 4–9,12–15). Aliquots withdrawn at times indicated were resolved in a native gel. Positions of prespliceosome (A) and spliceosome (B) are indicated.

A compensatory base change in U1 snRNA partially suppresses the U+2A 5′SS mutation

The observed inhibition of splicing detected with U+2A pre-mRNA could result from a block at the early stages of spliceosome assembly, prior to Prp8 function. To suppress defects in early recognition of the U+2A 5′SS, we have constructed a merodiploid strain that in addition to a wild-type chromosomal U1 snRNA gene contains also a mutant copy on a plasmid. In the suppressor U1–7U snRNA, the pairing between U1 and canonical U+2 at the 5′SS is restored (Fig. 4A). A detectable growth defect was observed in strains transformed with U1–7U snRNA; the doubling time for the haploid or merodiploid strains carrying wild-type U1 snRNA was ∼1.5× shorter than that of strains carrying U1–7U snRNA (data not shown). Efficient expression of U1–7U snRNA in these cells was confirmed independently by primer extension analysis of RNAs isolated from whole cell splicing extracts (Fig. 4B).

The restored pairing between U1 snRNA and intron position +2 was tested in vitro by monitoring spliceosome assembly on U+2A pre-mRNAs. Clearly, suppression of U+2A by the compensatory U1–7U mutation greatly improves formation of prespliceosomes (Fig. 4C, cf. lanes 1–3 and 4–9). The overall activity of the extracts used can be assessed in parallel reactions in the presence of wild-type or 3′SS mutant pre-mRNAs, where spliceosome assembly is not affected by 5′SS recognition (Fig. 4C, lanes 10–15; data not shown). In the presence of U1–7U RNA the ratio of spliceosomes to prespliceosomes assembled on U+2A pre-mRNA is slightly higher (∼1.5- to 2-fold) for the prp8 suppressor than for wild-type PRP8 extracts (Fig. 4C, cf. lanes 4–6 and 7–9). However, even in prp8 suppressor extracts, spliceosome formation on U+2A pre-mRNA is strongly reduced as compared to wild-type or 3′SS mutant precursors (Fig. 4C, cf. lanes 4–9 and 12–15), suggesting that yet another factor(s) affects spliceosome formation and/or stability under these conditions.

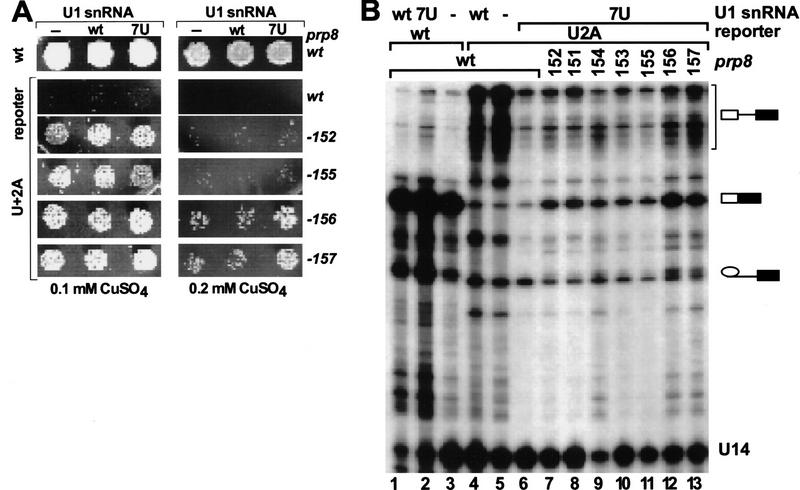

Consistent with the substantial improvement in prespliceosome and spliceosome levels, the compensatory U1–7U mutation exhibits significant suppression of the first step of U+2A pre-mRNA splicing in vitro (data not shown) and in vivo (Fig. 5B, lanes 5,6; Table 2). However, the second step is unaffected, as indicated both by the lack of suppression of growth defects on copper plates (Fig. 5A) and by primer extension analysis (Fig. 5B; Table 2). Similarly, in the presence of U1–7U most of the prp8 alleles do not significantly improve splicing in vivo (Fig. 5A,B; Table 2). Only prp8-156 and prp8-157, two of the strongest alleles, grow better in the presence of U1–7U, being able to sustain growth even in 0.2 mm CuSO4 (Fig. 5A). For these two alleles the M/L ratio in the presence of U1–7U is ∼8-fold higher than that for the wild-type PRP8 and ∼s1.5-fold higher than that for the same prp8 alleles in the absence of exogenous U1 snRNA (Table 2).

Figure 5.

The suppressor effect of the U1–7U snRNA and selected prp8 alleles on splicing of U+2A pre-mRNA reporters. (A) Copper growth phenotypes of the wild-type and selected prp8 suppressor strains (as indicated at right) in the presence of the wild-type or U+2A ACT1–CUP1 reporter (as indicated at left). Strains containing no additional copy, a wild-type, or U1–7U snRNA, as indicated, were plated in the presence of 0.1 mm (left) and 0.2 mm (right) CuSO4 in the media. (B) Primer extension analysis of total RNA isolated from strains containing a wild-type (lanes 1–6) or suppressor prp8 alleles (lanes 7–13), as well as an additional copy of the wild-type (lanes 1,4), U1–7U (lanes 2,6–13), or no U1 snRNA (lanes 3,5). Positions of U14, pre-mRNA, mRNA and lariat intermediates are indicated.

Therefore, splicing of U+2A pre-mRNA is inhibited at the stage of spliceosome assembly prior to U2 snRNP binding (prespliceosome formation). Suppression of U+2A by U1–7U snRNA efficiently overcomes this assembly defect; however, subsequent spliceosome formation or its stability is still limiting. In the presence of U1–7U snRNA, the strongest prp8 alleles offer a modest improvement of the second step of splicing, suggesting that for these prp8 suppressors in the presence of wild-type U1 the level of first-step intermediates may be limiting for splicing. Thus, 5′SS:U1 snRNA pairing strongly influences spliceosome formation and affects the first, but not the second, step of splicing. Independently, Prp8 interacts functionally with both splice sites at the later stage of splicing, affecting the efficiency of the second catalytic step.

Discussion

Despite intensive studies, details of the molecular mechanism of pre-mRNA splicing remain unknown. SnRNAs have been identified as important components of the spliceosome and, by analogy to self-splicing group II introns, implicated in formation of the catalytic center (for review, see Moore et al. 1993; Nilsen 1998). Multiple RNA–RNA interactions, involving both snRNA and pre-mRNA sequences, control spliceosome assembly and have a critical role in the formation of its active site. However, essential spliceosomal components include also >fifty distinct protein factors, whose specific function is mostly unknown (Krämer 1996; Will and Lührmann 1997; Burge et al. 1999). One of the most intriguing spliceosomal proteins is Prp8, a large, highly conserved component of U5 snRNP (Anderson et al. 1989; Hodges et al. 1995; Luo et al. 1999). The high conservation of Prp8 sequences (62% identity between human and yeast) may reflect multiple, specific interactions of this factor with a number of other proteins in the spliceosome, as seen in the case of TBP within TFIID (Burley and Roeder 1996). Prp8 interacts genetically and/or physically with U4, U5, and U6 snRNAs (Dix et al. 1998; Collins and Guthrie 1999; Kuhn et al. 1999), forms a stable complex with several other U5 snRNP proteins (Achsel et al. 1998), and interacts with Prp28 and Prp40 (Strauss and Guthrie 1991; Kao and Siliciano 1996; Abovich and Rosbash 1997), as well as with the 5′SS, branch site, PPY tract, and the 3′SS, that is, all important splicing signals within the pre-mRNA (Wyatt et al. 1992; MacMillan et al. 1994; Teigelkamp et al. 1995; Umen and Guthrie 1995, 1996; Reyes et al. 1996; Chiara et al. 1997).

Alleles of PRP8 suppress both 5′SS and 3′SS mutations

The hPrp8 forms a highly specific, homogenous UV cross-link with the GU dinucleotide at the 5′ end of the intron that maps to five amino acids in the carboxy-terminal portion of the human protein, 1894QACLK1898 (Reyes et al. 1996, 1999), corresponding to 1966SAAMS1970 in yPrp8 (Fig. 1A). If the cross-link site lies within the segment of Prp8 that interacts directly with the GU dinucleotide, appropriate compensatory mutations in this part of the protein are expected to yield a suppressor phenotype in yeast. By selecting for dominant prp8 alleles that suppress U+2A 5′SS, we have identified three distinct mutations that produce the desired phenotype. One of them, N1869D, is located ∼100 amino acids upstream of the mapped site of the cross-link, whereas the other two, T1982A and V1987A, are positioned 14 and 19 amino acids downstream of that site, respectively. The selected prp8 alleles affect 5′SS mutations in a highly specific manner: Whereas U+2A suppression is the strongest, U+2G is only minimal, and G+1A is not detectable at all. Furthermore, the E1960K mutation found in one of the previously identified prp8 alleles [prp8-101, PPY tract suppressor (Umen and Guthrie 1995)] is positioned just a few amino acids from the 5′SS:hPrp8 cross-link; however, it does not suppress either 5′SS or 3′SS mutations, indicating high specificity of this effect.

Interestingly, all prp8 alleles isolated as 5′SS suppressors also suppress mutations at the 3′SS, both in vivo and in vitro, improving the second step of splicing. Collins and Guthrie (1999) isolated a number of prp8 alleles with the same property and reclassified all of the previously identified 3′SS suppressors (amino acids 1397–1609; Umen and Guthrie 1996) as the general ‘splice site suppressors.’ These results indicate that the same or an overlapping region of Prp8 is involved in a functional interaction with both splice sites.

Prp8 suppression of the 5′SS mutation affects late steps in splicing

The prp8 alleles identified in this work suppress splice site defects, affecting primarily the second step of splicing. However, the overall level of suppression is moderate (mRNA represents only 12% for U+2A pre-mRNA splicing with the strongest suppressor, prp8-156, as compared to 87% for the splicing of the wild-type pre-mRNA with wild-type PRP8). Similarly, neither spliceosome formation nor splicing could be detected in vitro using U+2A pre-mRNA in the presence of prp8 suppressor extracts, suggesting that recognition of U+2 is limited by factor(s) other than Prp8 alone.

An obvious candidate for one such factor is U1 snRNA, known to recognize the 5′SS early in the reaction (Rosbash and Séraphin 1991). Expression of the suppressor U1–7U snRNA significantly improves prespliceosome assembly in vitro and partially suppresses the first, but not the second, step of splicing in vivo. The additive effect of combining U1–7U and prp8 suppressors is detectable in vivo only for the two strongest alleles; prp8-156 and prp8-157. Thus, for prp8-151-5 alleles the overall splicing efficiency is not limited by recognition of the 5′SS by U1 snRNP but, rather, by the inefficient second step. Although prp8 suppression of the second step defects suggests a functional interaction of Prp8 with U+2 after the first step, it does not preclude earlier interactions, indicating only that they are not limiting.

In addition to Prp8, other spliceosomal components are also known to interact with the GU dinucleotide. Close contact of U+2 at the 5′SS with U6 snRNA has been documented by UV cross-linking (Sontheimer and Steitz 1993; Kim and Abelson 1996), and U6 snRNA forms an extended genetic interaction with the 5′SS sequence, including positions G+1 and U+2 (Luukkonen and Séraphin 1998a,b). Thus, Prp8 is not the sole determinant of the GU dinucleotide and thus the isolated prp8 alleles are not expected to completely suppress mutations at the U+2 position. Compelling evidence for a genetic interaction between both splice sites, Prp8 and U6 snRNA, is presented in Collins and Guthrie (1999).

Another mutation in the same region of Prp8 (T1861P, prp8-201) suppresses a U4 snRNA mutation, suggesting that Prp8 is also involved in destabilization of U4/U6 snRNA duplex to allow U6:U2 snRNA pairing (Kuhn et al. 1999). Thus, together with U5 and U6 snRNAs (and possibly other factors), Prp8 interacts with the 5′SS during spliceosome formation. Subsequently, it is involved in destabilization of U4:U6 snRNA pairing, and then in interactions with the PPY tract, branch site, and both splice sites, making an important contribution to formation of the catalytic center.

Interactions near the catalytic center

Mutations found in the strongest prp8 suppressors map to two distinct regions separated by an ∼100-amino-acid block of sequence which contains one of the two most highly conserved segments of the protein. The unusually high level of identity (92%) between yeast and human sequences in this segment suggests a protein domain implicated in a conserved interaction with another spliceosomal component, by analogy to other highly conserved protein sequences (e.g., TBP; Burley and Roeder 1996). The strongest prp8 suppressor alleles bear mutations at both ends of this conserved segment (N1869D, T1982A, and V1987A). All mutations conferring a strong suppressor phenotype fall at highly conserved positions within the Prp8 sequence. The identity of the other partner in this suspected conserved interaction is not known; however, it could include any one of the U5 snRNPs stably associated with Prp8 (Achsel et al. 1998). Interestingly, the second of these most highly conserved blocks in Prp8 (97% identity between yeast and human, amino acids 1600–1662) is located in proximity of another cluster of splice site suppressor mutations. The suppressor mutations located at distant positions in the Prp8 sequence may be brought together in the folded structure and act through direct contacts with the splice sites. Alternatively, suppression could occur through indirect, allosteric effects, perhaps involving altered interactions with neighboring proteins.

The prp8 suppressors cause a relaxed, rather than altered, specificity toward the intron mutations, suggesting that they affect the structure near the splice sites, loosening it and thus allowing for utilization of mutant sequences. The same prp8 suppressors are able to recognize and utilize the wild-type splice site signals. Interestingly, among the three strongest suppressor mutations in Prp8, two involve substitutions of a bulkier amino acid with an alanine residue. Biochemical evidence also indicates a tight and highly specific contact between the 5′SS and Prp8 (Reyes et al. 1996; Sha et al. 1998). At position U+2, modifications as small as replacement of hydrogen (1.2 Å) with a methyl group (2 Å) cause significant interference in the 5′SS:hPrp8 cross-link, spliceosome formation, and splicing (Reyes et al. 1996). Similarly, placing a bulky (9 Å) group near the 5′SS junction (from position −2 to +4 or +5) strongly interferes with spliceosome formation and splicing, whereas the inhibitory effect of a smaller, 3 Å group is less severe and confined to a narrower region (position −2 to +3; Sha et al. 1998). Thus, it is possible that U+2A and U+2G mutations tested in this study inhibit splicing through a steric hindrance in interactions at the catalytic center. Alternatively, the mutated bases at position +2 cannot form some uridine-specific contacts with the conserved residues in Prp8 and/or U6 snRNA.

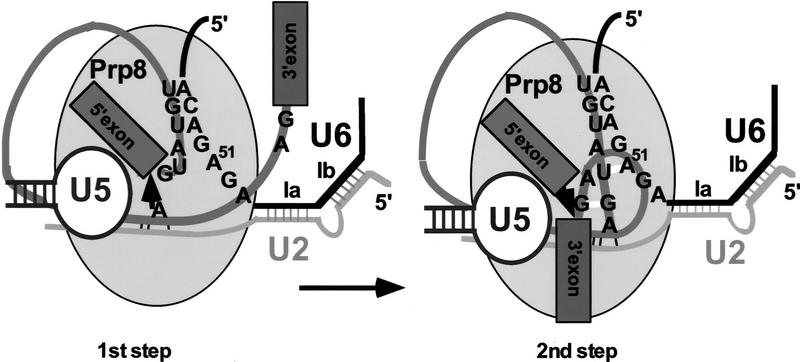

The results of this work contribute to our understanding of the complex net of interactions at the center of the spliceosome. Prp8 must be considered an important, integral component of the catalytic center (Fig. 6). Its specific interactions with the 5′SS suggested by earlier studies in the HeLa cell system (Reyes et al. 1996, 1999) have been extended by identification of prp8 suppressors located near the site of the cross-link. This suggests that the same region of Ppr8 may be involved in contacting the 5′SS prior to catalysis and, subsequently, both splice sites at the second splicing step. Formally, the 5′SS:Prp8 interaction (or some of its elements) established early in the reaction could be maintained throughout the first (and possibly the second) step of splicing, perhaps without undergoing any major rearrangements. Although the GU:hPrp8 cross-link decreases dramatically over time (Reyes et al. 1996), some form of Prp8 interaction with the 5′SS is maintained beyond spliceosome assembly, as the 5′SS:Prp8 cross-link is detected even after the first catalytic step (Wyatt et al. 1992; Teigelkamp et al. 1995). The observed effect could also result from an indirect interaction of Prp8 with other elements of the catalytic center, for example, U2 or U6 snRNAs. However, the striking proximity of some of the prp8 mutations that affect the second step of splicing and the mapped site of the physical contact between the 5′SS and hPrp8 early in the reaction would argue against it. Although some conformational change at the catalytic center is clearly required between the first and the second catalytic steps (Moore and Sharp 1993; Sontheimer et al. 1997), this rearrangement may maintain at least some interactions between Prp8 and the 5′SS (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

A possible model of interactions at the first and the second step of splicing. At the first step of the reaction the 5′SS is properly positioned for the nucleophilic attack (arrow) by the branch site A; the 3′SS is not required at the catalytic center. The carboxy-terminal segment of Prp8 interacts with the 5′SS at this stage, as indicated by a number of biochemical studies. Before or during the second step of splicing both 5′SS and 3′SS are positioned in close proximity of each other, the ACAGA box of U6 snRNA, and the carboxy-terminal segment of Prp8 described in this paper. The proximity of all these elements at the catalytic center may explain the suppressor effect of the same prp8 alleles on both the 5′SS and 3′SS mutations during the second step of splicing. Noncanonical interactions: G-G between the terminal intron residues, U-A between the second (U+2) intron residue, and A51 of U6 snRNA are indicated by short white bars. In addition, Watson–Crick interactions between U6 and U2 snRNA (helix Ia, Ib), branch site and U2 snRNA, and the 5′SS and U6 snRNA are indicated.

Although further studies are necessary to analyze the specific role of Prp8, its established functional interactions with both the 5′SS and 3′SS make it, together with U2 and U6 snRNAs, an important component of the catalytic center.

Materials and methods

Strains and plasmids

All yeast strains and plasmids used in this work were the kind gift of C. Collins and C. Guthrie (UCSF). Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain YJU75 (MATa, ade2, cup1Δ::ura3, his3, leu2, lys2, prp8Δ::LYS2, trp1, pJU169 (PRP8, URA3, CEN, ARS) was used for all experiments (Umen and Guthrie 1996). The NruI site (PRP8 position 6018 in pJU225-1; no change in amino acid sequence) was introduced by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis (Kunkel et al. 1987) with the GCATTTTCGCGACTTACAC oligonucleotide. pJU225-1 is a derivative of pJU225 (PRP8, TRP1, 2μ) (Umen and Guthrie 1996). The identity of all plasmids was confirmed by sequencing. The U1–7U mutation was introduced into pJPS21 (HIS3, 2μ) containing the yU1 snRNA gene. The 5′ end of the U1 gene was amplified by PCR using YU1A 5′-GCGAATTCATTCCCTAGCTCTTG-3′ and YU1B 5′-CTCCTCTGATATCTTAAGGAAAGTATGAGGATTTTA-3′ primers. The mutated A creating U1–7U is shown in boldface type, and restriction sites used are underlined. The ACT1–CUP1 reporters (LEU2, 2μ) were described previously (Lesser and Guthrie 1993b).

Yeast manipulations

All methods for manipulation of yeast were performed according to standard procedures (Becker and Guarente 1991; Guthrie and Fink 1991). pJU225-1 cleaved with MscI and NruI to remove a 297-nucleotide fragment (amino acids 5725–6018) was cotransformed with PRP8-derived PCR fragments generated using yp8-2 and yp8-3 oligonucleotides into yeast strain YJU75. Transformed cells were plated directly onto Phytagar (GIBCO) plates containing CuSO4 (Sherman 1991).

Preparation of mutagenic libraries

A randomly mutagenized library was prepared as described (Caldwell and Joyce 1992). A 690-nucleotide fragment (yPRP8, amino acids 5506–6195) was amplified using yp8-2 5′-AACTCCTCAAACTATGCCGAG-3′ and yp8-3 5′-TCTGCCGTA-CTCAGTCAAAATC-3′ primers. Libraries containing randomized positions S1966A1967 and M1969S1970 were prepared by PCR with yp8-5 5′-GAGCTGCGACTACCATTTNN(C/G)NN(C/G)GCAATGTCAATAGATAAAC-3′ and yp8-6 5′-GAGCTGCGACTACCATTTTCAGCTGCANN(C/G)NN(C/G)ATAGAT-AAACTTTCTGA-3′ primers (randomized positions are underlined), in combination with yp8-7 5′-AAATGGTAGTCGCAGCTCTGTT-3′, yp8-2, and yp8-3 primers. The resulting 690-nucleotide fragments were introduced into the yPRP8 gene by in vivo gap repair (see Umen and Guthrie 1996).

Primer extension

Total yeast RNA prepared by the glass bead extraction method was used for primer extension as described (Frank and Guthrie 1992), using primers YU14 5′-ACGATGGGTTCGTAAGCGTACTCCTACCGTGG-3′, complementary to U14 snRNA, and YAC6 5′-GGCACTCATGACCTTC-3′, complementary to exon 2 of ACT1. Annealing reaction (6 μl, containing 4 μg of total yeast RNA and 32P-labeled primers in 50 mm Tris at pH 8.3, 10 mm DTT, 60 mm NaCl) was heated for 3 min at 90°C, cooled to 55°C, and frozen in dry ice/ethanol. Extension products were separated in 7% polyacrylamide/8 m urea gels. To distinguish between the wild-type and U1–7U snRNAs (Fig. 4), primer YU1C 5′-CTTCTTGATCTCCTCTGATATCTT-3′, was used. The extension reaction contained 0.4 mm dNTPs and 0.2 mm ddTTP, as indicated.

In vitro splicing reactions

Yeast whole cell extracts were prepared as described (Umen and Guthrie 1995). Pre-mRNAs containing wild-type, U+2A, or UAG → UUG mutations were prepared from ACT1–CUP1 constructs by T7 RNA polymerase transcription. Splicing reactions (10 μl) containing 1.5 mm MgCl2, 2.5 mm ATP, 3% PEG-8000, 60 mm KPO4, 3 μl of yeast extract, and 32P-labeled pre-mRNA were incubated at 25°C for the time indicated. Reactions were stopped with buffer R [2 mm Mg(OAc)2, 50 mm HEPES-Na+, 2 μg/μl total HeLa RNA], incubated on ice for 10 min, and resolved in native polyacrylamide/agarose gels (Pikielny et al. 1986). Splicing intermediates and products were isolated by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, and resolved in 7% polyacrylamide/8M urea gels.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Cathy Collins and Christine Guthrie for providing yeast strains, plasmids, and abundant advice on yeast manipulations. We thank Charles Query and Lisa Dailey for critical comments on the manuscript. J.L.R. was supported by a John Calvert Eistenstein Fellowship. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant GM49044) to M.M.K.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL konarsk@rockvax.rockefeller.edu; FAX (212) 327-7147.

References

- Abovich N, Rosbash M. Cross-intron bridging interactions in the yeast commitment complex are conserved in mammals. Cell. 1997;89:403–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achsel T, Ahrens K, Brahms H, Teigelkamp S, Lührmann R. The human U5-220kD protein (hPrp8) forms a stable RNA-free complex with several U5-specific proteins, including an RNA unwindase, a homologue of ribosomal elongation factor EF-2, and a novel WD-40 protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6756–6766. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GJ, Bach M, Lührmann R, Beggs JD. Conservation between yeast and man of a protein associated with U5 snRNP. Nature. 1989;342:819–821. doi: 10.1038/342819a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DM, Guarente L. High-efficiency transformation of yeast by electroporation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:182–187. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge CB, Tuschl TH, Sharp PA. Splicing of precursors to mRNAs by the spliceosomes. In: Gesteland RF, Cech TR, Atkins JF, editors. RNA world II. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Burley SK, Roeder RG. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID) Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell RC, Joyce GF. Randomization of genes by PCR mutagenesis. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;2:28–33. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiara MD, Paladjian L, Kramer RF, Reed R. Evidence that U5 snRNP recognizes the 3′ splice site for catalytic step II in mammals. EMBO J. 1997;16:4746–4759. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C. and C. Guthrie. 1999. Prp8 constrains a tertiary interaction at the spliceosomal active site. Genes & Dev. (this issue).

- Dietrich RC, Incorvaia R, Padgett RA. Terminal intron dinucleotide sequences do not distinguish between U2- and U12- dependent introns. Mol Cell. 1997;1:151–160. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix I, Russell CS, O’Keefe RT, Newman AJ, Beggs JD. Protein-RNA interactions in the U5 snRNP of S. cerevisiae. RNA. 1998;4:1239–1250. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298981109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouser LA, Friesen JD. Mutations in a yeast intron demonstrate the importance of specific conserved nucleotides for the two stages of nuclear mRNA splicing. Cell. 1986;45:81–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank D, Guthrie C. An essential splicing factor, SLU7, mediates 3′ splice site choice in yeast. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:2112–2124. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.11.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie C, Fink GR. In: Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Abelson JN, Simon MI, editors. Vol. 194. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges PE, Jackson SP, Brown JD, Beggs JD. Extraordinary sequence conservation of the PRP8 splicing factor. Yeast. 1995;11:337–342. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier A, Rodriguez JR, Rosbash M. A quantitative analysis of the effects of 5′ junction and TACTAAC box mutants and mutant combinations on yeast mRNA splicing. Cell. 1985;43:423–430. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandels-Lewis S, Séraphin B. Role of U6 snRNA in 5′ splice site selection. Science. 1993;262:2035–2039. doi: 10.1126/science.8266100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao H-Y, Siliciano PG. Identification of Prp40, a novel essential yeast splicing factor associated with the U1 snRNP. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:960–967. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Najarian R, Haslinger A, Valenzuela P, Welch J. Primary structure and transcription of an amplified locus: The CUP1 locus of yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1984;81:337–341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Abelson J. Site-specific crosslinks of yeast U6 snRNA to the pre-mRNA near the 5′ splice site. RNA. 1996;2:995–1010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konforti BB, Konarska MM. U4/U5/U6 snRNP recognizes the 5′ splice site in the absence of U2 snRNP. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:1962–1973. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konforti BB, Koziolkiewicz MJ, Konarska MM. Disruption of base pairing between the 5′ splice site and the 5′ end of U1 snRNA is required for spliceosome assembly. Cell. 1993;75:863–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90531-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer A. The structure and function of proteins involved in mammalian pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:367–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn AN, Li Z, Brow DA. Splicing factor Prp8 governs U4/U6 RNA unwinding during activation of the spliceosome. Mol Cell. 1999;3:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel TA, Roberts JD, Zakour RA. Rapid and efficient site directed mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. In: Wu R, Grossman L, editors. Methods in enzymology, recombinant DNA. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 367–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser CF, Guthrie C. Mutations in U6 snRNA that alter splice site specificity: Implications for the active site. Science. 1993a;262:1982–1988. doi: 10.1126/science.8266093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Mutational analysis of pre-mRNA splicing in S. cerevisiae using a sensitive new reporter gene, CUP1. Genetics. 1993b;133:851–863. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.4.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.R., G.A. Moreau, N. Levin, and M.J. Moore. 1999. The human Prp8 protein is a component of both U2- and U12-dependent spliceosomes. RNA (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luukkonen BGM, Séraphin B. Genetic interaction between U6 snRNA and the first intron nucleotide in S. cerevisiae. RNA. 1998a;4:167–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— A role for U2/U6 helix Ib in 5′ splice site selection. RNA. 1998b;4:915–927. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan AM, Query CC, Allerson CR, Chen S, Verdine GL, Sharp PA. Dynamic association of proteins with the pre-mRNA branch region. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:3008–3020. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ, Sharp PA. Evidence for two active sites in the spliceosome provided by stereochemistry of pre-mRNA splicing. Nature. 1993;365:364–368. doi: 10.1038/365364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MJ, Query CC, Sharp PA. Splicing of precursors to mRNA by the spliceosome. In: Gesteland RF, Atkins JF, editors. The RNA world. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 303–357. [Google Scholar]

- Newman AJ, Norman C. U5 snRNA interacts with exon sequences at 5′ and 3′ splice sites. Cell. 1992;68:743–754. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen TW. RNA-RNA interactions in nuclear pre-mRNA splicing. In: Simons R, Grunberg-Manago M, editors. RNA structure and function. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1998. pp. 279–307. [Google Scholar]

- Pikielny CW, Rymond BC, Rosbash M. Electrophoresis of ribonucleoproteins reveals an ordered assembly pathway of yeast splicing complexes. Nature. 1986;324:341–345. doi: 10.1038/324341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JL, Kois P, Konforti BB, Konarska MM. The canonical GU dinucleotide at the 5′ splice site is recognized by p220 of the U5 snRNP within the spliceosome. RNA. 1996;2:213–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JL, Gustafson EH, Luo HR, Moore MJ, Konarska MM. The C-terminal region of hPrp8 interacts with the conserved GU dinucleotide at the 5′ splice site. RNA. 1999;5:167–179. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosbash M, Séraphin B. Who’s on first? The U1 snRNP-5′ splice site interaction and splicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:187–190. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin B, Green MR. Role of the 3′ splice site consensus sequence in mammalian pre-mRNA splicing. Nature. 1985;317:732–734. doi: 10.1038/317732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha M, Levy T, Kois P, Konarska MM. Probing of the spliceosome with site-specifically derivatized 5′ splice site RNA oligonucleotides. RNA. 1998;4:1069–1082. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PA, Burge CB. Classification of introns: U2-type or U12-type. Cell. 1997;91:875–879. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F. 1991. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sontheimer EJ, Steitz JA. The U5 and U6 snRNAs as active site components of the spliceosome. Science. 1993;262:1989–1996. doi: 10.1126/science.8266094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontheimer EJ, Sun S, Piccirilli JA. Metal ion catalysis during splicing of pre-mRNA. Nature. 1997;388:801–805. doi: 10.1038/42068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley JP, Guthrie C. An RNA switch at the 5′ splice site requires ATP and the DEAD box protein Prp28p. Mol Cell. 1999;3:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss EJ, Guthrie C. A cold-sensitive mRNA splicing mutant is a member of the RNA helicase gene family. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:629–641. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarn W-Y, Steitz JA. A novel spliceosome containing U11, U12, and U5 snRNPs excises a minor class (AT-AC) intron in vitro. Cell. 1996;84:801–811. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teigelkamp S, Newman AJ, Beggs JD. Extensive interactions of PRP8 protein with the 5′ and 3′ splice sites during splicing suggest a role in stabilization of exon alignment by U5 snRNA. EMBO J. 1995;14:2602–2612. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umen JG, Guthrie C. A novel role for a U5 snRNP protein in 3′ splice site selection. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:855–868. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Mutagenesis of the yeast gene PRP8 reveals domains governing the specificity and fidelity of 3′ splice site selection. Genetics. 1996;143:723–739. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayraghavan U, Parker R, Tamm J, Iimura Y, Rossi J, Abelson J, Guthrie C. Mutations in conserved intron sequences affect multiple steps in the yeast splicing pathway, particularly assembly of the spliceosome. EMBO J. 1986;5:1683–1695. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04412.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will CL, Lührmann R. Protein functions in pre-mRNA splicing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:320–328. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt JR, Sontheimer EJ, Steitz JA. Site-specific cross-linking of mammalian U5 snRNP to the 5′ splice site before the first step of pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2542–2553. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]