Abstract

Familial tumoral calcinosis (FTC) refers to a heterogeneous group of inherited disorders characterized by the occurrence of cutaneous and subcutaneous calcified masses. Two major forms of the disease are now recognized. Hyperphosphatemic FTC has been shown to result from mutations in three genes: fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23), coding for a potent phosphaturic protein, KL encoding Klotho, which serves as a co-receptor for FGF23, and GALNT3, which encodes a glycosyltransferase responsible for FGF23 O-glycosylation; defective function of any one of these three proteins results in hyperphosphatemia and ectopic calcification. The second form of the disease is characterized by absence of metabolic abnormalities, and is, therefore, termed normophosphatemic FTC. This variant was found to be associated with absence of functional SAMD9, a putative tumor suppressor and anti-inflammatory protein. The data gathered through the study of these rare disorders have recently led to the discovery of novel aspects of the pathogenesis of common disorders in humans, underscoring the potential concealed within the study of rare diseases.

Familial tumoral calcinosis (FTC) represents a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of inherited diseases manifesting with dermal and subcutaneous deposition of calcified materials. In recent years, the pathogenesis of these disorders has been elucidated, not only leading to delineation of the major pathways responsible for regulating extraosseous calcification, but also shedding new light on the pathogenesis of pathologies as common as renal failure and autoimmune diseases.

FAMILIAL TUMORAL CALCINOSIS: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The first clinical description of familial tumoral calcinosis (FTC) dates back to 1898 when two French dermatologists, Giard and Duret, reported for the first time the cardinal features of the disorder under the name endotheliome calcifié (Giard, 1898; Duret, 1899). The disease was later described in the German literature as lipocalcinogranulomatosis or Teutschlaender’s disease after the German dermatologist who studied a large number of such cases (Tseutschlaender, 1935). The term tumoral calcinosis was coined in the American literature by Inclan et al. (1943). Inclan et al. were also the first to accurately differentiate this inherited disease from other related but acquired conditions, which later became known as metastatic calcinosis and dystrophic calcinosis. Subsequently, numerous reports, initially emanating from travelers who had returned from Africa, indicated that the disease is apparently prevalent in this region of the world (McClatchie and Bremner, 1969; Owor, 1972). Despite these advances, it was not until 1996 that Smack et al. formally established the distinction between normophosphatemic (NFTC) and hyperphosphatemic FTC (HFTC) (Smack et al., 1996), a classification that proved to be instrumental in guiding the molecular studies that eventually led to the identification of the genetic basis of FTC.

FTC: EPIDEMIOLOGICAL, CLINICAL, AND BIOCHEMICAL FEATURES

As mentioned above, FTC has been mainly (but not exclusively) reported in Africa, the Middle-East, and in populations originating from these regions of the world. Its exact prevalence is unknown, but it is considered to be exceedingly rare. Although the disease was initially reported to be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion (Lyles et al., 1985), the recent identification of the genetic defects underlying all forms of FTC definitely established an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance (Topaz et al., 2004; Benet-Pages et al., 2005; Ichikawa et al., 2005).

Serum phosphate levels demarcate the two major subtypes of FTC: HFTC (MIM211900) and NFTC (MIM610455; Sprecher, 2007). Although these two disorders were initially considered part of a clinical continuum (Metzker et al., 1988), it is today clear that they represent distinct entities, not only at the metabolic level, but also at the clinical, epidemiological, and genetic (see below) levels.

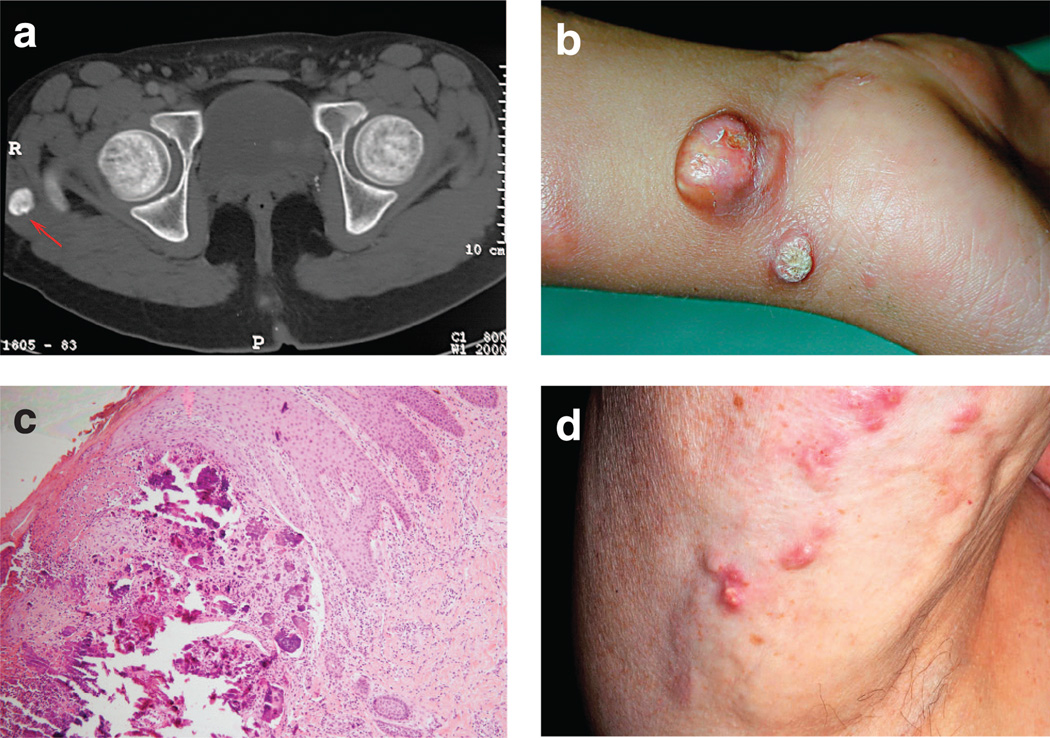

HFTC is generally characterized by a relatively late onset from the first to the third decade of life (Prince et al., 1982; Metzker et al., 1988; Slavin et al., 1993), although appearance of calcified nodules has been reported as early as at 6 weeks of age (Polykandriotis et al., 2004). It has been mainly reported in individuals of Middle Eastern and African origins (Metzker et al., 1988; Slavin et al., 1993). Many patients are often incidentally diagnosed while undergoing radiographic investigation for unrelated reasons. Slowly growing calcified masses develop mainly at periarticular locations, with a predilection for skin areas overlying large joints. The hips are most often involved. These calcified masses are initially asymptomatic, but progressively reach large sizes (up to 1.5 kg), thereby interfering with movements around the joints (Figure 1a). Ulceration is usually accompanied by intolerable pain and is occasionally associated with secondary infections, rarely reported as a cause of death (Sprecher, 2007). In some affected individuals, extracutaneous signs may predominate. Dental manifestations, including pulp calcifications and obliteration of the pulp cavity, may be prominent (Burkes et al., 1991; Campagnoli et al., 2006; Specktor et al., 2006); testicular microlithiasis has been reported as part of the disease (Campagnoli et al., 2006); angioid streaks and corneal calcifications have been observed as well (Ghanchi et al., 1996); and bone manifestations (diaphysitis and hyperostosis) may be more common than initially thought (Clarke et al., 1984; Mallette and Mechanick, 1987; Ballina-Garcia et al., 1996). HFTC has been reported in association with pseudoxanthoma elasticum (Mallette and Mechanick, 1987). Recently, a long-term follow-up study of one of the largest HFTC kindreds described revealed salient features of the disease, including overall good prognosis, lack of efficient treatments for the disorder apart from surgical removal of calcified tumors (most patients undergo over 20 major operations during their life time), and possible association with hypertension and pulmonary restrictive disease (Carmichael et al., 2009). Medical treatment is notoriously frustrating. Isolated reports have suggested benefit from combined treatment of HFTC with acetazolamide and sevelamer hydrochloride, a non-calcium phosphate binder (Garringer et al., 2006; Lammoglia and Mericq, 2009).

Figure 1. Clinical findings in FTC.

(a) Computed tomographic scan showing a calcified mass in the soft tissue adjacent to the right major Trochanter (red arrow). (b) Calcified tumor on the right wrist of a 5-year-old boy with NFTC. (c) A skin biopsy obtained from an 8-year-old female patient with NFTC have calcified materials in the upper and middle dermis (hematoxylin and eosin, × 400). (d) Calcified nodules in a 70-year-old patient with dermatomyositis and acquired calcinosis cutis.

NFTC seems to be even less prevalent than HFTC, with only six families reported to date (Topaz et al., 2006; Chefetz et al., 2008). The disease often initially manifests with a nonspecific erythematous rash and mucosal inflammation during the first year of life (Metzker et al., 1988; Katz et al., 1989). Inflammatory manifestations in the oral cavity can be particularly debilitating (Gal et al., 1994). This eruption heralds the progressive, but often rapid, development of small, acrally located calcified nodules, which almost invariably lead to ulceration of the overlying skin and discharge of chalky material (Figure 1b). Here too, unremitting pain and infection are major causes of morbidity.

Histopathologically (Figure 1c), two major stages in calcified tumor formation have been recognized: an active phase characterized by the presence of multinucleated giant cells and macrophages surrounding calcified deposits in the dermis, and a chronic or inactive phase associated with dense fibrous tissue (Veress et al., 1976). Biochemical analysis of extruded calcified masses indicated that they are mainly composed of calcium hydroxyapatite with amorphous calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate (Boskey et al., 1983).

As mentioned above, metabolic abnormalities are the major features distinguishing HFTC from NFTC. HFTC patients invariably show elevated levels of circulating phosphate (in the range of 5 to 7 mg dl−1, normal levels = 2.5–4.5mg dl−1 or 0.80–1.44 mmol), which are due to decreased fractional phosphate excretion through the kidney proximal tubules (White et al., 2006). Calcium levels are typically normal in HFTC, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D levels are normal or inappropriately elevated (Steinherz et al., 1985). In contrast, NFTC patients do not show any metabolic abnormality (Metzker et al., 1988; Topaz et al., 2006). In fact, these differences are very much reminiscent of the dichotomous nature of acquired calcinosis (Touart and Sau, 1998). Here, calcinosis can either manifest as a result of an underlying metabolic disorder as in chronic renal failure, or develop as a reaction to tissue damage, as in autoimmune diseases (Figure 1d) or as in atherosclerosis (Touart and Sau, 1998). When cutaneous calcinosis is due to deranged phosphate or calcium metabolism (e.g., chronic renal failure), it is termed metastatic calcinosis; by contrast, when it is secondary to tissue damage (e.g., autoimmune disease), it is known as dystrophic calcinosis (Touart and Sau, 1998). At this regard, clinical and metabolic features of HFTC very much resemble metastatic calcinosis, while NFTC models dystrophic calcinosis, thus suggesting that elucidation of the molecular basis of FTC may shed light on the pathogenesis of these two major forms of acquired calcinosis. This assumption was the impetus that drove a large international effort aimed at deciphering the molecular cause and biochemical mechanisms underlying the various forms of FTC.

MOLECULAR GENETICS OF HFTC

We owe to the study of rare diseases the discovery of many key physiological pathways (Antonarakis and Beckmann, 2006). In less than 5 years, the study of FTC has revealed a surprisingly intricate regulatory network of proteins responsible for regulation of phosphate homeostasis and extraosseous calcification (Sprecher, 2007; Chefetz and Sprecher, 2009).

Using homozygosity mapping, HFTC was initially mapped to 2q24–q31 and found to be associated with mutations in GALNT3, gene encoding a glycosyltransferase termed UDP-N-acetyl-α-d-galactosamine-polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-3 (ppGalNacT3; Topaz et al., 2004). ppGalNacT3 catalyses the initial step of O-glycosylation of serine and threonine residues, and is ubiquitously expressed (Ten Hagen et al., 2003; Wopereis et al., 2006). ppGalNacT3 is one of a family of 24 acetylgalactosaminyltransferases, which are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and play an important role in the development and maintenance of a variety of tissues (Ten Hagen et al., 2003). Most congenital disorders of glycosylation result from impaired N-glycosylation and are characterized by pleiotropic clinical manifestations (Freeze, 2006); in this regard, HFTC is unique in that it results from abnormal O-glycosylation and seems to be associated exclusively with ectopic calcification.

More than 10 mutations have so far been reported in GALNT3 (Topaz et al., 2004; Ichikawa et al., 2005, 2006; Campagnoli et al., 2006; Garringer et al., 2006, 2007; Specktor et al., 2006; Barbieri et al., 2007; Dumitrescu et al., 2009; Laleye et al., 2008); all of these are predicted or have been found (Topaz et al., 2005) to result in loss of function of ppGalNacT3. Deleterious alterations in GALNT3 were also found to underlie at least one additional autosomal recessive syndrome, hyperostosis–hyperphosphatemia syndrome (MIM610233), which, as HFTC, is also associated with elevated levels of serum phosphate (Melhem et al., 1970; Altman and Pomerance, 1971; Mikati et al., 1981). This syndrome manifests with episodes of excruciating pain associated with swelling, along the long bones. Despite the fact that HFTC and hyperostosis–hyperphosphatemia syndrome manifest phenotypically in two different tissues, skin and bone, mutations in the same gene, GALNT3, and in one instance, the very same mutation (Frishberg et al., 2005), were found to underlie both syndromes (Ichikawa et al., 2007a; Dumitrescu et al., 2009; Olauson et al., 2008; Gok et al., 2009). Interestingly, coexistence of the two diseases in one family has been reported (Narchi, 1997; Nithyananth et al., 2008). In fact, phenotypic heterogeneity seems to be quite characteristic of the HFTC group of diseases, with a widely variable spectrum of disease severity and tissue involvement (Sprecher, 2007).

Large-scale screening of HFTC families revealed that GALNT3 mutations cannot be found in all HFTC families. In parallel, several groups noticed that HFTC represents in many ways the metabolic mirror image of another rare disorder known as hypophosphatemic rickets (Bastepe and Juppner, 2008). Three genetic types of hypophosphatemic rickets have been described: X-linked, autosomal recessive, and autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets, which were shown to be caused by mutations in PHEX, DMP1, and fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23), respectively (Juppner, 2007; Bastepe and Juppner, 2008; Shaikh et al., 2008). FGF23 encodes the FGF23, a potent phosphaturic protein responsible for promoting phosphate excretion through kidney (Strom and Juppner, 2008). DMP1 and PHEX function as negative regulators of the activity of FGF23 (Quarles, 2008). FGF23 mainly originates from mineralized tissues, although it has also been detected in other tissues such as kidneys, liver, and brain (Yoshiko et al., 2007). Recent data indicate that FGF23 signals through the FGFR1(IIIc) receptor, which is converted into a functional FGF23 receptor by Klotho (Urakawa et al., 2006), a molecule previously shown in mice to regulate aging-related processes (Kurosu and Kuro-o, 2008). Despite the fact that activating mutations in FGFR3 have been linked to hypophosphatemia (Quarles, 2008), it seems that this receptor does not mediate the renal effects of FGF23 (Liu et al., 2008).

Assessment of HFTC patients without GALNT3 mutations revealed that while dominant gain-of-function mutations in FGF23 result in hypophosphatemic rickets, recessive loss-of-function mutations in the same gene cause HFTC (Araya et al., 2005; Benet-Pages et al., 2005; Chefetz et al., 2005; Larsson et al., 2005b; Lammoglia and Mericq, 2009; Masi et al., 2009). HFTC-causing mutations in FGF23 are associated with a variety of biochemical abnormalities such as abnormal secretion of the intact molecule from the Golgi (Benet-Pages et al., 2005) and decreased FGF23 stability (Larsson et al., 2005a; Garringer et al., 2008).

FGF23 activity is partially processed intracellularly by subtilisin-like proprotein convertases at a consensus sequence between residues R179 and S180 (Benet-Pages et al., 2004). Dominant mutations associated with hypophosphatemic rickets affect the proteolytic site of FGF23, preventing proper degradation of the molecule (Shimada et al., 2002). In contrast, HFTC-causing mutations in FGF23 have been shown to result in enhanced proteolytic processing of FGF23 (Larsson et al., 2005a; Garringer et al., 2008). In addition, a recent study showed that a missense mutation in KL, encoding Klotho, also results in a phenotype very much resembling HFTC (Ichikawa et al., 2007b). This mutation was found to result in decreased expression of Klotho and concomitant decreased FGF23 signaling, leading to a severe form of HFTC characterized by widespread cutaneous and visceral calcifications, diffuse osteopenia, and sclerodactyly (Ichikawa et al., 2007b).

PATHOGENESIS OF HFTC

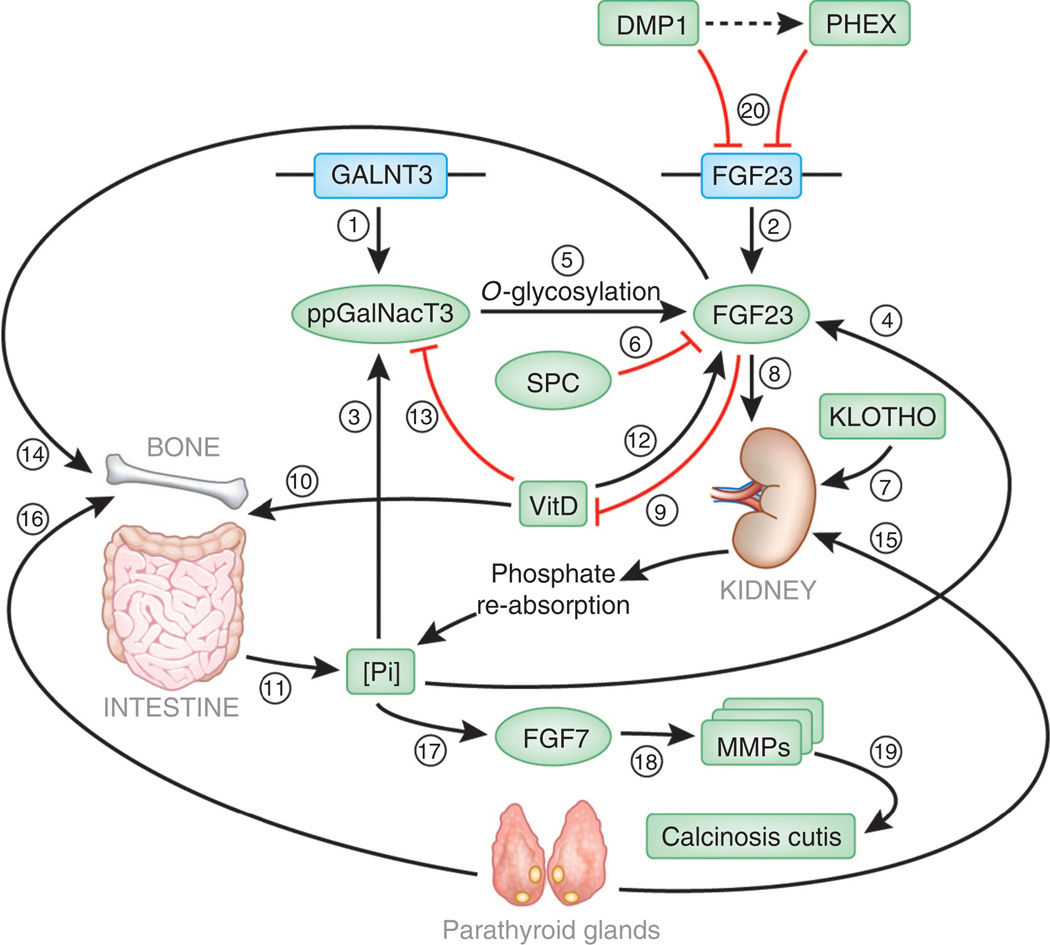

In summary, (1) HFTC can be caused by mutations in at least three genes (GALNT3, FGF23, and KL); (2) loss-of-function sequence alterations in GALNT3 are associated with two distinct phenotypes, HFTC and HSS; and (3) loss-of-function mutations in FGF23 also cause HFTC, while dominant gain-of-function mutations in the same gene are associated with hypophosphatemic rickets (2000), which is also due to mutations in DMP1 (Feng et al., 2006; Lorenz-Depiereux et al., 2006) and PHEX (Table 1 and Strom and Juppner, 2008). These findings raised the possibility that these various molecules may be part of a single physiological pathway. Recent data lend support to this hypothesis (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity among disorders of phosphate metabolism associated with abnormal ppGalNacT3 and FGF23 function

| Disease | OMIM | Phenotype | Gene (protein) | Protein function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis | 211900 | Calcified masses over large joints, occasionally visceral calcifications | GALNT3 (ppGalNacT3) | Initiates mucin type O-glycosylation |

| Hyperostosis hyperphosphatemia syndrome | 610233 | Repeated attacks of painful swellings of the long bones; on radiography, cortical hyperostosis, periosteal reaction, diaphysitis | GALNT3 (ppGalNacT3) | Initiates mucin type O-glycosylation |

| Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis | 211900 | Calcified masses over large joints, more frequent visceral calcifications than with GALNT3 mutations | FGF23 (FGF23) | Regulates phosphate reabsorption |

| Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets | 193100 | Growth retardation, osteomalacia, rickets, bone pain | FGF23 (FGF23) | Regulates phosphate reabsorption |

| Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis | 211900 | Widespread cutaneous and visceral calcifications, diffuse osteopenia and sclerodactyly | KL (Klotho) | Involved in the regulation of phosphate and calcium levels |

| X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets | 307800 | Growth retardation, osteomalacia, rickets, bone pain | PHEX (PHEX) | Protease, which regulates FGF23 expression and bone mineralization |

| Autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets | 241520 | Growth retardation, osteomalacia, rickets, bone pain | DMP1 (DMP1) | Regulates FGF23 expression and bone mineralization |

| Epidermal nevus1 | 162900 | Hyperkeratotic papules/plaques distributed in a linear or segmental fashion | FGFR3 (FGFR3) | Serves as receptor for fibroblast growth factors such as FGF1 |

FGF23, fibroblast growth factor-23; ppGalNacT3, polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-3.

In selected cases of epidermal nevus, increased levels of FGF23 associated with hypophosphatemic rickets are observed due to end-organ gain-of-function mutations.

Figure 2. FTC-associated molecules and the regulation of phosphate homeostasis.

Two genes have been found to be associated with classical FTC, GALNT3 encoding ppGalNacT3 (1) and FGF23 encoding the phosphatonin FGF23 (2). Increased phosphate levels upregulate the activity of ppGAlNacT3 (3) as well as FGF23 (4). ppGalNacT3 then O-glycosylates FGF23 (5), thereby protecting it from the proteolytic activity of subtilisin-like proprotein convertases (SPC) (6). FGF23 then signals through its receptor in the presence of Klotho (7), resulting in decreased transport of phosphate through the Na–Pi transporters (8) and inhibiting vitamin-D1 hydroxylation (9). Since 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D acts by promoting phosphate absorption through the small intestine (10), the effect of FGF23 on vitamin-D metabolism results in decreased entry of phosphate into the circulation (11). In contrast, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D augments FGF23 signaling (12), but inhibits ppGalNacT3 expression (13), thereby establishing a double-regulatory feedback loop mechanism. Of note, FGF23 influences bone mineralization (14). The entire system is also under the regulation of parathyroid hormone, which promotes phosphate excretion through kidney (15) and mobilizes phosphate from the bone (16), thus integrating calcium- and phosphate-regulatory systems. As a consequence of hyperphosphatemia, FGF7 is induced (17), which results in expression and activation of several MMPs (18), which are known to mediate ectopic calcification (19). Since FGF7 mainly originates from the dermis, this may explain the propensity of ectopic calcification to develop in the skin in HFTC. Additional elements involved in the regulation of FGF23 activity include PHEX and DMP1, which inhibit FGF23 activity through still poorly understood mechanisms (possibly including a direct interaction between them) (20). Loss-of-function mutations in the genes encoding these two molecules are associated with increased FGF23 activity and hypophosphatemia.

For decades, phosphate homeostasis has been thought to be maintained through concerted actions of parathyroid hormone, which inhibits renal phosphate reabsorption and mobilizes bone calcium and phosphate, and 1,25-hydroxyvitamin-D, which increases phosphate transport across small intestine (Schiavi and Moe, 2002; Quarles, 2008). More recently, a group of proteins, known as phosphatonins, has been shown to regulate phosphate levels in the circulation independently of calcium (Schiavi and Moe, 2002). FGF23 is the phosphatonin that has been best characterized so far.

As mentioned above, FGF23 signaling is dependent on the presence of Klotho (Kurosu and Kuro, 2009). Thus FGF23 mainly targets organs expressing Klotho such as parathyroid glands and kidneys (Razzaque and Lanske, 2007).

FGF23 inhibits phosphate reabsorption through the major sodium-phosphate transporters, NaPi-IIa and NaPi-IIc, thus allowing efficient counter-regulation of excessive circulating levels of phosphate (Saito et al., 2003; Razzaque, 2009). FGF23 also suppresses CYP27B1, which catalyzes 1-α-hydroxylation of 25-hydroxy-vitamin-D and activates CYP24, which inactivates 1,25-hydroxyvitamin-D (Liu and Quarles, 2007). Interestingly, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D was found to upregulate FGF23 expression in bone, thereby establishing a novel endocrine feedback loop between these two hormones (Kolek et al., 2005; Saito et al., 2005). Not only does FGF23 deficiency alter phosphate homeostasis, it also leads to abnormal mineralization, suggesting that FGF23 plays a role in bone formation (Sitara et al., 2008), perhaps in a paracrine manner since osteocytes in bone are the major source of FGF23 (Yoshiko et al., 2007). The clinical phenotype associated with decreased Klotho activity very much overlaps with that exhibited by FGF23-deficient individuals, except for the fact that HFTC caused by KL mutations is associated with hypercalcemia as well as elevated serum levels of parathyroid hormone and FGF23 (Ichikawa et al., 2007b). This may in fact relate to the fact that Klotho plays major direct (e.g., regulation of the secretion of the parathyroid hormone) and indirect (e.g., decreased 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D3 activity) roles in the maintenance of calcium homeostasis (Nabeshima and Imura, 2008). Of note, independently of regulation of phosphate and calcium homeostasis, Klotho plays a number of other important roles such as controlling insulin signaling (Razzaque and Lanske, 2007; Kurosu and Kuro-o, 2008; Nabeshima and Imura, 2008). Taken altogether, these data suggest that FGF23 mainly serves as a counter-regulatory hormone to offset the effect of excessive 1,25-hydroxy-vitamin-D.

As mentioned above, activity of FGF23 is mainly modulated by a poorly understood process of proteolysis at a furin-like convertase sequence motif. PHEX and DMP1 may promote the activity of the subtilisin-like protease(s) responsible for mediating FGF23 cleavage (Quarles, 2008). More interestingly, FGF23 was found to be a substrate for ppGalNacT3-mediated O-glycosylation. ppGalNacT3 was found to catalyze the glycosylation of the recognition site of subtilisin-like proprotein convertase, thereby protecting FGF23 from proteolysis (Kato et al., 2006). FGF23 secretion was also found to be dependent on ppGalNacT3-mediated O-glycosylation (Kato et al., 2006). Thus, since loss-of-function mutations in GALNT3, FGF23, and KL all result in decreased activity of FGF23, it is not surprising that they also yield overlapping phenotypes (Table 1).

Currently very little is known about the factors regulating the expression of GALNT3. Phosphate was found to stimulate the expression and/or activity of ppGalNacT3 (Chefetz et al., 2009) as well as FGF23 (Saito et al., 2005), while it induced a marked decrease in the activity of 1-α-hydroxylase, thereby decreasing the amount of active vitamin-D3 (Perwad et al., 2005). Since 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D was shown to decrease the expression of GALNT3 (Chefetz et al., 2009), this complex feedback loop enables for restraining the activity of FGF23 once it is no more required, namely when phosphate level is back to normal.

A major question, which remained largely unanswered, is why does HFTC-associated ectopic calcification mainly affect cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues in the face of hyperphosphatemia affecting equally all tissues. Recent data have implicated FGF7, another phosphatonin, which is secreted in response to hyperphosphatemia (characteristically found in HFTC; Carpenter et al., 2005), is produced exclusively in the dermis (auf demKeller et al., 2004), and is capable of triggering the activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs; Putnins et al., 1995; Shin et al., 2002; Simian et al., 2001). Interestingly, MMPs have been shown to mediate ectopic calcification in vascular tissues (Satta et al., 2003; Qin et al., 2006). Accordingly, fibroblasts derived from HFTC patients or normal fibroblasts knocked down for GALNT3 showed increased activation of several key MMPs (Chefetz et al., 2009).

MOLECULAR GENETICS OF NFTC

The fact that NFTC has so far been reported exclusively among Yemenite Jews suggested that a founder mutation may underlie the disease in this community, which in turn allowed homozygosity mapping to be used to locate the disease gene. Through study of five affected kindreds, the disease gene was found to map to 7q21, confirming at the genetic level the fact that NFTC and HFTC (which maps to 2q) are two separate non-allelic disorders, despite clinical similarities between them (Topaz et al., 2006). Candidate gene screening revealed initially a missense mutation in SAMD9 segregating with the disease phenotype in all families (Topaz et al., 2006). The mutation was found to result in SAMD9 protein degradation, suggesting a loss-of-function effect (Topaz et al., 2006). In agreement with these results, a second nonsense mutation was later identified in an additional kindred of Jewish Yemenite origin (Chefetz et al., 2008). Although at first, identification of two mutations in SAMD9 causing a similar phenotype may have been expected, these data are surprising given the rarity of the disease and the very small size of the Jewish Yemenite population. In fact, the occurrence of two independent genetic events within a very close and small population may reflect a selection effect (Chefetz et al., 2008). Unfortunately, very little is currently known about the physiological function of SAMD9 so that no functional rationale has been provided so far to explain this effect.

PATHOGENESIS OF NFTC

SAMD9 is a 1,589-amino-acid cytoplasmic protein ubiquitously expressed in all adult and fetal tissues except for fetal brain and skeletal muscle (Topaz et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007). Apart from an N-terminal SAM domain, it lacks homology to any known family of proteins.

The fact that calcification in NFTC is often preceded by an inflammatory rash (Metzker et al., 1988; Katz et al., 1989) suggests a role for SAMD9 in the regulation of inflammation within the skin. In line with this hypothesis, tumor necrosis factor-α as well as osmotic shock were found to induce SAMD9 expression in a p38- and NF-κB-dependant manner (Chefetz et al., 2008). This indicates that SAMD9 may be involved in tumor necrosis factor-α-induced cell apoptosis. It is, therefore, of interest to note that the expression of SAMD9 was found to be significantly downregulated in a large proportion of tumors of various origins (Li et al., 2007). Decreased expression of SAMD9 was found to be associated with increased cell proliferation and decreased apoptosis (Li et al., 2007). In addition, transfection of tumor cells with SAMD9 was accompanied by increased apoptotic activity, decreased cell invasion in an in vitro assay, and decreased cancer cell proliferation (Li et al., 2007). Tumor cells overexpressing SAMD9 formed tumor of a lower volume as compared with wild-type cells (Li et al., 2007). Altogether, these data indicate that SAMD9 may function as a tumor-suppressor gene. In support of this hypothesis, recent data show that myelodysplatic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia, and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia are associated with a microdeletion on 7q21.3 spanning SAMD9, and its paralog, SAMD9L (Asou et al., 2009). How are these two putative functions of SAMD9 (anti-inflammatory and tumor-suppressive) mechanistically related is not yet known.

RELEVANCE TO ACQUIRED DISEASES

The data reviewed above indicate the importance of ppGalNacT3, FGF23, Klotho, and SAMD9 in the prevention of abnormal calcification in peripheral tissues. Their involvement in the pathogenesis of relevant human pathologies is currently the focus of intense research efforts.

A growing body of evidence points to extraosseous calcification as a major cause or predictor of morbidity and mortality in humans. Vascular calcification has been shown to quite accurately predict mortality, mainly due to cardiovascular causes, in large cohorts (Thompson and Partridge, 2004; Barasch et al., 2006). Among factors that have been known for long to be associated with the propensity to develop cardiovascular diseases, are elevated levels of circulating phosphate (Kestenbaum et al., 2005; Tonelli et al., 2005; Giachelli, 2009), which has been shown to induce ectopic calcification (Jono et al., 2000). Hyperphosphatemia is most likely acting independently of more conventional cardiovascular risk factors (Lippi et al., 2009), suggesting that interventions specifically directed at attenuating extraosseous calcification may provide substantial additional benefit to individuals at risk (Schmitt et al., 2006). Several studies have asked whether the newly discovered regulators of phosphate homeostasis have a predictive value of their own for pathologies known to be associated with elevated levels of circulating phosphate. Although FGF23 levels were found to also correlate with mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis, total-body atherosclerosis in the general population, and progression of chronic renal disease, they were found to predict outcome independently of phosphate levels (Fliser et al., 2007; Gutierrez et al., 2008; Mirza et al., 2009); in contrast, FGF23 levels were found to be associated with renal stone formation only if due to increased urinary excretion of phosphate (Rendina et al., 2006).

These data suggest a potential benefit for novel therapies based on modulation of the activity of the various molecules known to play a role in the pathogenesis of inherited FTC. Tetracyclines have been shown to ameliorate the course of ectopic calcinosis (Robertson et al., 2003; Boulman et al., 2005) as well as to inhibit the activity of MMPs (Kim et al., 2005; Qin et al., 2006), which may play a role in the pathogenesis of FTC (Chefetz et al., 2009). Interestingly, we were recently able to show that doxycycline significantly upregulates the expression of ppGalNacT3 (Chefetz and Sprecher, 2009), suggesting the need to assess the efficacy of tetracyclines in disorders associated with deranged activity of the ppGalNacT3–FGF23 axis.

CONCLUSIONS

The study of FTC phenotypes has led to delineation of novel biochemical pathways of importance for maintenance of phosphate balance. It exemplifies remarkably the immense potential concealed within the study of rare diseases, for only through the study of human subjects could the function of ppGal-NacT3, FGF23, and Klotho have been delineated. Indeed, although ppGal-NacT3-deficient mice feature a normal lifespan, show hyperphosphatemia, and inappropriately normal levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin-D3, in analogy with what is seen in HFTC patients, the mice do not show ectopic calcifications and males are infertile, which are not features of HFTC in humans (Ichikawa et al., 2009). In contrast to humans, FGF23-deficient mice have a shortened lifespan and show growth retardation, infertility, muscle atrophy, hypoglycemia, and visceral calcification (Kuro-o et al., 1997; Shimada et al., 2004). In fact FGF23 mice resemble very much Klotho-deficient mice (Kuro-o et al., 1997), even though Klotho deficiency manifests differently in humans than FGF23 deficiency (Ichikawa et al., 2007b). More interestingly, SAMD9 does not exist at all in the murine genome (Li et al., 2007). Thus, through study of an exceedingly rare phenotype the major regulatory molecules of critical importance for maintenance of phosphate homeostasis and prevention of ectopic calcification have been discovered and are on the verge of being used to refine therapeutic approaches to much more common ailments in humans such as renal failure and autoimmune diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to the patients and their families for participation in our studies. I also thank our many collaborators, including Orit Topaz, Ilana Chefetz, Dov Hershkovitz, Gabriele Richard, Margarita Indelman, Aryeh Metzker, Ulla Mandel, Mordechai Mizrachi, John G Cooper, Polina Specktor, Vered Friedman, Gila Maor, Israel Zelikovic, Sharon Raimer, Yoram Altschuler, Mordechai Choder, Dani Bercovich, Jouni Uitto, and Reuven Bergman, for their invaluable contribution to the various studies reviewed above. I also thank Dr Dorit Goldsher (Rambam Health Care campus) for providing a picture of a computed tomographic scan in HFTC. This work was supported in part by grants provided by the Israel Science Foundation, the Israel Ministry of Health, and NIH/NIAMS grant R01 AR052627.

Abbreviations

- FGF23

fibroblast growth factor-23

- FTC

familial tumoral calcinosis

- HFTC

hyerphosphatemic FTC

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NFTC

normophosphatemic FTC

- ppGalNacT3

polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-3

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Altman HS, Pomerance HH. Cortical hyperostosis with hyperphosphatemia. J Pediatr. 1971;79:874–875. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(71)80411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonarakis SE, Beckmann JS. Mendelian disorders deserve more attention. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:277–282. doi: 10.1038/nrg1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araya K, Fukumoto S, Backenroth R, Takeuchi Y, Nakayama K, Ito N, et al. A novel mutation in fibroblast growth factor 23 gene as a cause of tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5523–5527. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asou H, Matsui H, Ozaki Y, Nagamachi A, Nakamura M, Aki D, et al. Identification of a common microdeletion cluster in 7q21.3 subband among patients with myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- auf demKeller U, Krampert M, Kumin A, Braun S, Werner S. Keratinocyte growth factor: effects on keratinocytes and mechanisms of action. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:607–612. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballina-Garcia FJ, Queiro-Silva R, Fernandez-Vega F, Fernandez-Sanchez JA, Weruaga-Rey A, Perez-Del Rio MJ, et al. Diaphysitis in tumoral calcinosis syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:2148–2151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasch E, Gottdiener JS, Marino Larsen EK, Chaves PH, Newman AB. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in community-dwelling elderly individuals with calcification of the fibrous skeleton of the base of the heart and aortosclerosis (The Cardiovascular Health Study) Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1281–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri AM, Filopanti M, Bua G, Beck-Peccoz P. Two novel nonsense mutations in GALNT3 gene are responsible for familial tumoral calcinosis. J Hum Genet. 2007;52:464–468. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastepe M, Juppner H. Inherited hypophosphatemic disorders in children and the evolving mechanisms of phosphate regulation. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2008;9:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s11154-008-9075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Pages A, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Zischka H, White KE, Econs MJ, Strom TM. FGF23 is processed by proprotein convertases but not by PHEX. Bone. 2004;35:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Pages A, Orlik P, Strom TM, Lorenz-Depiereux B. An FGF23 missense mutation causes familial tumoral calcinosis with hyperphosphatemia. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:385–390. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boskey AL, Vigorita VJ, Sencer O, Stuchin SA, Lane JM. Chemical, microscopic, and ultrastructural characterization of the mineral deposits in tumoral calcinosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;178:258–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulman N, Slobodin G, Rozenbaum M, Rosner I. Calcinosis in rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkes EJ, Jr, Lyles KW, Dolan EA, Giammara B, Hanker J. Dental lesions in tumoral calcinosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1991;20:222–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnoli MF, Pucci A, Garelli E, Carando A, Defilippi C, Lala R, et al. Familial tumoral calcinosis and testicular microlithiasis associated with a new mutation of GALNT3 in a White family. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:440–442. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.026369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael KD, Bynum JA, Evans EB. Familial tumoral calcinosis: a forty-year follow-up on one family. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:664–671. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter TO, Ellis BK, Insogna KL, Philbrick WM, Sterpka J, Shimkets R. Fibroblast growth factor 7: an inhibitor of phosphate transport derived from oncogenic osteomalacia-causing tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1012–1020. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chefetz I, Ben Amitai D, Browning S, Skorecki K, Adir N, Thomas MG, et al. Normophosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis is caused by deleterious mutations in SAMD9, encoding a TNF-alpha responsive protein. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1423–1429. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chefetz I, Heller R, Galli-Tsinopoulou A, Richard G, Wollnik B, Indelman M, et al. A novel homozygous missense mutation in FGF23 causes familial tumoral calcinosis associated with disseminated visceral calcification. Hum Genet. 2005;118:261–266. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chefetz I, Kohno K, Izumi H, Uitto J, Richard G, Sprecher E. GALNT3, a gene associated with hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis, is transcriptionally regulated by extracellular phosphate and modulates matrix metalloproteinase activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chefetz I, Sprecher E. Familial tumoral calcinosis and the role of O-glycosylation in the maintenance of phosphate homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:847–852. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke E, Swischuk LE, Hayden CK., Jr Tumoral calcinosis, diaphysitis, and hyperphosphatemia. Radiology. 1984;151:643–646. doi: 10.1148/radiology.151.3.6718723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu CE, Kelly MH, Khosravi A, Hart TC, Brahim J, White KE, et al. A case of familial tumoral calcinosis/hyperostosis–hyperphosphatemia syndrome due to a compound heterozygous mutation in GALNT3 demonstrating new phenotypic features. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1273–1278. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0775-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret MH. Tumeurs multiples and singuliers de bourses sereuses. Bull Mem Soc Ant. 1899;74:725–731. [Google Scholar]

- Feng JQ, Ward LM, Liu S, Lu Y, Xie Y, Yuan B, et al. Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1310–1315. doi: 10.1038/ng1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliser D, Kollerits B, Neyer U, Ankerst DP, Lhotta K, Lingenhel A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) predicts progression of chronic kidney disease: the Mild to Moderate Kidney Disease (MMKD) Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2600–2608. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeze HH. Genetic defects in the human glycome. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:537–551. doi: 10.1038/nrg1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishberg Y, Topaz O, Bergman R, Behar D, Fisher D, Gordon D, et al. Identification of a recurrent mutation in GALNT3 demonstrates that hyperostosis–hyperphosphatemia syndrome and familial tumoral calcinosis are allelic disorders. J Mol Med. 2005;83:33–38. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0610-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal G, Metzker A, Garlick J, Gold Y, Calderon S. Head and neck manifestations of tumoral calcinosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:158–166. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garringer HJ, Fisher C, Larsson TE, Davis SI, Koller DL, Cullen MJ, et al. The role of mutant UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-d-galactosamine-polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferase 3 in regulating serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 and matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein in heritable tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4037–4042. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garringer HJ, Malekpour M, Esteghamat F, Mortazavi SM, Davis SI, Farrow EG, et al. Molecular genetic and biochemical analyses of FGF23 mutations in familial tumoral calcinosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E929–E937. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90456.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garringer HJ, Mortazavi SM, Esteghamat F, Malekpour M, Boztepe H, Tanakol R, et al. Two novel GALNT3 mutations in familial tumoral calcinosis. Am J Med Genet. 2007;143A:2390–2396. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanchi F, Ramsay A, Coupland S, Barr D, Lee WR. Ocular tumoral calcinosis. A clinicopathologic study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:341–345. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130337022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giard A. Sur la calcification tibernale. CR Soc Biol. 1898;10:1015–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Giachelli CM. The emerging role of phosphate in vascular calcification. Kidney Int. 2009;75:890–897. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gok F, Chefetz I, Indelman M, Kocaoglu M, Sprecher E. Newly discovered mutations in the GALNT3 gene causing autosomal recessive hyperostosis–hyperphosphatemia syndrome. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:131–134. doi: 10.1080/17453670902807482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, Rauh-Hain JA, Tamez H, Shah A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa S, Guigonis V, Imel EA, Courouble M, Heissat S, Henley JD, et al. Novel GALNT3 mutations causing hyperostosis–hyperphosphatemia syndrome result in low intact fibroblast growth factor 23 concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007a;92:1943–1947. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa S, Imel EA, Kreiter ML, Yu X, Mackenzie DS, Sorenson AH, et al. A homozygous missense mutation in human KLOTHO causes severe tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Invest. 2007b;117:2684–2691. doi: 10.1172/JCI31330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa S, Imel EA, Sorenson AH, Severe R, Knudson P, Harris GJ, et al. Tumoral calcinosis presenting with eyelid calcifications due to novel missense mutations in the glycosyltransferase domain of the GALNT3 gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4472–4475. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa S, Lyles KW, Econs MJ. A novel GALNT3 mutation in a pseudoautosomal dominant form of tumoral calcinosis: evidence that the disorder is autosomal recessive. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2420–2423. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa S, Sorenson AH, Austin AM, Mackenzie DS, Fritz TA, Moh A, et al. Ablation of the Galnt3 gene leads to low-circulating intact fibroblast growth factor 23 (Fgf23) concentrations and hyperphosphatemia despite increased Fgf23 expression. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2543–2550. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inclan A, Leon P, Camejo MG. Tumoral calcinosis. JAMA. 1943;121:490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Jono S, McKee MD, Murry CE, Shioi A, Nishizawa Y, Mori K, et al. Phosphate regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Circ Res. 2000;87:E10–E17. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juppner H. Novel regulators of phosphate homeostasis and bone metabolism. Ther Apher Dial. 2007;11 Suppl 1:S3–S22. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-9987.2007.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Jeanneau C, Tarp MA, Benet-Pages A, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Bennett EP, et al. Polypeptide GalNAc-transferase T3 and familial tumoral calcinosis. Secretion of fibroblast growth factor 23 requires O-glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18370–18377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Ben-Yehuda A, Machtei EE, Danon YL, Metzker A. Tumoral calcinosis associated with early onset periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:643–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, Patterson DJ, Seliger SL, Young B, et al. Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:520–528. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Luo L, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. Doxycycline inhibits TGF-beta1-induced MMP-9 via Smad and MAPK pathways in human corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:840–848. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolek OI, Hines ER, Jones MD, LeSueur LK, Lipko MA, Kiela PR, et al. 1Alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 upregulates FGF23 gene expression in bone: the final link in a renal–gastrointestinal–skeletal axis that controls phosphate transport. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G1036–G1042. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00243.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosu H, Kuro-o M. The Klotho gene family and the endocrine fibroblast growth factors. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:368–372. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282ffd994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosu H, Kuro OM. The Klotho gene family as a regulator of endocrine fibroblast growth factors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;299:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laleye A, Alao MJ, Gbessi G, Adjagba M, Marche M, Coupry I, et al. Tumoral calcinosis due to GALNT3 C.516-2A > T mutation in a black African family. Genet Couns. 2008;19:183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammoglia JJ, Mericq V. Familial tumoral calcinosis caused by a novel FGF23 mutation: response to induction of tubular renal acidosis with acetazolamide and the non-calcium phosphate binder sevelamer. Horm Res. 2009;71:178–184. doi: 10.1159/000197876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson T, Davis SI, Garringer HJ, Mooney SD, Draman MS, Cullen MJ, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-23 mutants causing familial tumoral calcinosis are differentially processed. Endocrinology. 2005a;146:3883–3891. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson T, Yu X, Davis SI, Draman MS, Mooney SD, Cullen MJ, et al. A novel recessive mutation in fibroblast growth factor-23 causes familial tumoral calcinosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005b;90:2424–2427. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CF, MacDonald JR, Wei RY, Ray J, Lau K, Kandel C, et al. Human sterile alpha motif domain 9, a novel gene identified as down-regulated in aggressive fibromatosis, is absent in the mouse. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi G, Montagnana M, Salvagno GL, Targher G, Guidi GC. Relationship between serum phosphate and cardiovascular risk factors in a large cohort of adult outpatients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;84:e3–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Quarles LD. How fibroblast growth factor 23 works. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1637–1647. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Vierthaler L, Tang W, Zhou J, Quarles LD. FGFR3 and FGFR4 do not mediate renal effects of FGF23. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2342–2350. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz-Depiereux B, Bastepe M, Benet-Pages A, Amyere M, Wagenstaller J, Muller-Barth U, et al. DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1248–1250. doi: 10.1038/ng1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles KW, Burkes EJ, Ellis GJ, Lucas KJ, Dolan EA, Drezner MK. Genetic transmission of tumoral calcinosis: autosomal dominant with variable clinical expressivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60:1093–1096. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-6-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallette LE, Mechanick JI. Heritable syndrome of pseudoxanthoma elasticum with abnormal phosphorus and vitamin D metabolism. Am J Med. 1987;83:1157–1162. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90960-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi L, Gozzini A, Franchi A, Campanacci D, Amedei A, Falchetti A, et al. A novel recessive mutation of fibroblast growth factor-23 in tumoral calcinosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1190–1198. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClatchie S, Bremner AD. Tumoral calcinosis—an unrecognized disease. Br Med J. 1969;1:153–155. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5637.142-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem RE, Najjar SS, Khachadurian AK. Cortical hyperostosis with hyperphosphatemia: a new syndrome? J Pediatr. 1970;77:986–990. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(70)80081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzker A, Eisenstein B, Oren J, Samuel R. Tumoral calcinosis revisited—common and uncommon features. Report of ten cases and review. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:128–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00442209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikati MA, Melhem RE, Najjar SS. The syndrome of hyperostosis and hyperphosphatemia. J Pediatr. 1981;99:900–904. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza MA, Hansen T, Johansson L, Ahlstrom H, Larsson A, Lind L, et al. Relationship between circulating FGF23 and total body atherosclerosis in the community. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3125–3131. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima Y, Imura H. Alpha-Klotho: a regulator that integrates calcium homeostasis. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:455–464. doi: 10.1159/000112824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narchi H. Hyperostosis with hyperphosphatemia: evidence of familial occurrence and association with tumoral calcinosis. Pediatrics. 1997;99:745–748. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nithyananth M, Cherian VM, Paul TV, Seshadri MS. Hyperostosis and hyperphosphataemia syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:e350–e352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olauson H, Krajisnik T, Larsson C, Lindberg B, Larsson TE. A novel missense mutation in GALNT3 causing hyperostosis-hyperphosphataemia syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:929–934. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owor R. Tumoral calcinosis in Uganda. Trop Geogr Med. 1972;24:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perwad F, Azam N, Zhang MY, Yamashita T, Tenenhouse HS, Portale AA. Dietary and serum phosphorus regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 expression and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D metabolism in mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5358–5364. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polykandriotis EP, Beutel FK, Horch RE, Grunert J. A case of familial tumoral calcinosis in a neonate and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:563–567. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince MJ, Schaeffer PC, Goldsmith RS, Chausmer AB. Hyperphosphatemic tumoral calcinosis: association with elevation of serum 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol concentrations. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:586–591. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-96-5-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnins EE, Firth JD, Uitto VJ. Keratinocyte growth factor stimulation of gelatinase (matrix metalloproteinase-9) and plasminogen activator in histiotypic epithelial cell culture. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:989–994. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12606233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X, Corriere MA, Matrisian LM, Guzman RJ. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition attenuates aortic calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1510–1516. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000225807.76419.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarles LD. Endocrine functions of bone in mineral metabolism regulation. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3820–3828. doi: 10.1172/JCI36479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque MS. FGF23-mediated regulation of systemic phosphate homeostasis: is Klotho an essential player? Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F470–F476. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90538.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque MS, Lanske B. The emerging role of the fibroblast growth factor-23-klotho axis in renal regulation of phosphate homeostasis. J Endocrinol. 2007;194:1–10. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina D, Mossetti G, De Filippo G, Cioffi M, Strazzullo P. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is increased in calcium nephrolithiasis with hypophosphatemia and renal phosphate leak. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:959–963. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson LP, Marshall RW, Hickling P. Treatment of cutaneous calcinosis in limited systemic sclerosis with minocycline. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:267–269. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.3.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H, Kusano K, Kinosaki M, Ito H, Hirata M, Segawa H, et al. Human fibroblast growth factor-23 mutants suppress Na+dependent phosphate co-transport activity and 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2206–2211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207872200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H, Maeda A, Ohtomo S, Hirata M, Kusano K, Kato S, et al. Circulating FGF-23 is regulated by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and phosphorus in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2543–2549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408903200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satta J, Oiva J, Salo T, Eriksen H, Ohtonen P, Biancari F, et al. Evidence for an altered balance between matrix metalloproteinase-9 and its inhibitors in calcific aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:681–688. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00529-0. discussion 688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavi SC, Moe OW. Phosphatonins: a new class of phosphate-regulating proteins. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2002;11:423–430. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt CP, Odenwald T, Ritz E. Calcium, calcium regulatory hormones, and calcimimetics: impact on cardiovascular mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:S78–S80. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh A, Berndt T, Kumar R. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by the phosphatonins and other novel mediators. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1203–1210. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0751-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, et al. Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:561–568. doi: 10.1172/JCI19081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Muto T, Urakawa I, Yoneya T, Yamazaki Y, Okawa K, et al. Mutant FGF-23 responsible for autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets is resistant to proteolytic cleavage and causes hypophosphatemia in vivo. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3179–3182. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.8.8795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EY, Ma EK, Kim CK, Kwak SJ, Kim EG. Src/ERK but not phospholipase D is involved in keratinocyte growth factor-stimulated secretion of matrix metalloprotease-9 and urokinase-type plasminogen activator in SNU-16 human stomach cancer cell. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128:596–602. doi: 10.1007/s00432-002-0388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simian M, Hirai Y, Navre M, Werb Z, Lochter A, Bissell MJ. The interplay of matrix metalloproteinases, morphogens and growth factors is necessary for branching of mammary epithelial cells. Development. 2001;128:3117–3131. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitara D, Kim S, Razzaque MS, Bergwitz C, Taguchi T, Schuler C, et al. Genetic evidence of serum phosphate-independent functions of FGF-23 on bone. PLoS Genet. 2008;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000154. e1000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin RE, Wen J, Kumar D, Evans EB. Familial tumoral calcinosis. A clinical, histopathologic, and ultrastructural study with an analysis of its calcifying process and pathogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:788–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smack D, Norton SA, Fitzpatrick JE. Proposal for a pathogenesis-based classification of tumoral calcinosis. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:265–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb02999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Specktor P, Cooper JG, Indelman M, Sprecher E. Hyperphosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis caused by a mutation in GALNT3 in a European kindred. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:487–490. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0377-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher E. Tumoral calcinosis: new insights for the rheumatologist into a familial crystal deposition disease. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9:237–242. doi: 10.1007/s11926-007-0038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinherz R, Chesney RW, Eisenstein B, Metzker A, DeLuca HF, Phelps M. Elevated serum calcitriol concentrations do not fall in response to hyperphosphatemia in familial tumoral calcinosis. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139:816–819. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1985.02140100078036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom TM, Juppner H. PHEX, FGF23, DMP1 and beyond. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:357–362. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282fd6e5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Hagen KG, Fritz TA, Tabak LA. All in the family: the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology. 2003;13:1R–6R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson GR, Partridge J. Coronary calcification score: the coronary-risk impact factor. Lancet. 2004;363:557–559. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)15544-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, Gao Z, Curhan G. Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation. 2005;112:2627–2633. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.553198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topaz O, Bergman R, Mandel U, Maor G, Goldberg R, Richard G, et al. Absence of intraepidermal glycosyltransferase ppGal-Nac-T3 expression in familial tumoral calcinosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:211–215. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000158298.02545.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topaz O, Indelman M, Chefetz I, Geiger D, Metzker A, Altschuler Y, et al. A deleterious mutation in SAMD9 causes normophosphatemic familial tumoral calcinosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:759–764. doi: 10.1086/508069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topaz O, Shurman DL, Bergman R, Indelman M, Ratajczak P, Mizrachi M, et al. Mutations in GALNT3, encoding a protein involved in O-linked glycosylation, cause familial tumoral calcinosis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:579–581. doi: 10.1038/ng1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touart DM, Sau P. Cutaneous deposition diseases. Part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:527–544. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70001-5. 5quiz 545–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseutschlaender O. Uber progressive lipogranulomatose der muskulatur. Zugleich ein beitrag zur pathogenese der myopathia osteoplystica progressive. Klin Wochenschr. 1935;13:451–453. [Google Scholar]

- Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, Iijima K, Hasegawa H, Okawa K, et al. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006;444:770–774. doi: 10.1038/nature05315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veress B, Malik MO, El Hassan AM. Tumoral lipocalcinosis: a clinicopathological study of 20 cases. J Pathol. 1976;119:113–118. doi: 10.1002/path.1711190206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KE, Larsson TE, Econs MJ. The roles of specific genes implicated as circulating factors involved in normal and disordered phosphate homeostasis: frizzled related protein-4, matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein, and fibroblast growth factor 23. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:221–241. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wopereis S, Lefeber DJ, Morava E, Wevers RA. Mechanisms in protein O-glycan biosynthesis and clinical and molecular aspects of protein O-glycan biosynthesis defects: a review. Clin Chem. 2006;52:574–600. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.063040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiko Y, Wang H, Minamizaki T, Ijuin C, Yamamoto R, Suemune S, et al. Mineralized tissue cells are a principal source of FGF23. Bone. 2007;40:1565–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]